Jammu and Kashmir (princely state)

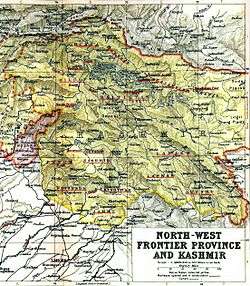

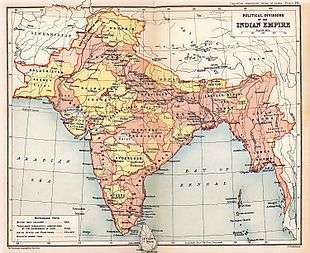

Jammu and Kashmir was, from 1846 until 1952, a princely state of the British Empire in India and ruled by a Jamwal Rajput Dogra Dynasty.[1] The state was created in 1846 from the territories previously under Sikh Empire after the First Anglo-Sikh War. The East India Company annexed the Kashmir Valley,[2] Jammu, Ladakh, and Gilgit-Baltistan from the Sikhs, and then transferred it to Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu in return for an indemnity payment of 7,500,000 Nanakshahee Rupees.

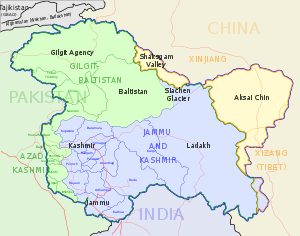

At the time of the British withdrawal from India, Maharaja Hari Singh, the ruler of the state, preferred to become independent and remain neutral between the successor dominions of India and Pakistan.[3] However, an uprising in the western districts of the State followed by an attack by raiders from the neighbouring Northwest Frontier Province, supported by Pakistan, put an end to his plans for independence. On 26 October 1947, the Maharaja signed the Instrument of Accession joining the Dominion of India in return for military aid.[4] The western and northern districts presently known as Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan passed to the control of Pakistan, while the remaining territory became the Indian state Jammu and Kashmir.[5]

Establishment

Jammu State

The Dogra state in Jammu was established by Dhruv Dev, of the Jamuwal (Jamwal) family, during the declining years of the Mughal Empire in the 18th century. The Jammu state then asserted its supremacy among the 'Dugar' states to the south of the Kashmir Valley. Its ascent reached its peak under Dhruv Dev's successor Raja Ranjit Dev (r. 1728–1780), who was widely respected among the hill states.[6][7]. Towards the end of Ranjit Dev's rule, the Sikh Misls (misls) gained ascendency, and Jammu began to be contested by the Bhangi, Kanhaiya and Sukerchakia misls. Around 1770, the Bhangi misl attacked Jammu and forced Ranjit Dev to become a tributary. Brij Lal Dev, his successor, was defeated by the Sukerchakia Misl under Mahan Singh, who sacked Jammu and plundered it. Thus Jammu lost its supremacy over the surrounding country.[8]

In 1808, Jammu itself was annexed to the Sikh Empire by Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the son of Mahan Singh.[9]

Gulab Singh

Gulab Singh, Dhruv Dev's direct descendant, was 16 years old when Jammu was annexed to the Sikh Empire. Gulab Singh and his two brothers, Dhyan Singh and Suchet Singh, went on to enrol with the Sikh forces. Gulab Singh soon distinguished himself in battle, and was awarded a Jagir near Jammu. He was also allowed to keep an independent force. After the conquest of Kishtwar (1821) and the subjugation of Rajouri, he was made a hereditary Raja of Jammu in 1822, with an annual allowance of 300,000 rupees. Ranjit Singh personally installed him as the Raja of Jammu. His brother Dhyan Singh received Poonch and Suchet Singh Ramnagar. Thus the Jammu state was reestablished after a gap of 20 years under the suzerainty of the Sikh Empire, Gulab Singh proceeded to regain its preeminence among the hill states.[10][11]

By 1827, Gulab Singh brought under his control all the principalities lying between Kashmir and Jammu.[12] Dhyan Singh became the Lord Chamberlain and, later, Prime Minister for Ranjit Singh. Gulab Singh acquired fame in the Sikh court as a warrior and an able manager of the State's affairs.[13]

In 1832, after the death of Hari Singh Nalwa in the Battle of Jamrud, the Sudhan tribe of Poonch rose in revolt in Mong. Gulab Singh was given the task of crushing the rebellion. After defeating insurgents in Hazara and Murree hills, Gulab Singh made Kahuta his headquarter to deal with Sudhan insurgents. A Sudhan, Shams Khan had raised the standard of revolt and had captured hill forts from a Raja. Gulab Singh placed one Rupee over the head of man, woman or child connected to the insurgents, this way about 6,000 Sudhans perished in the hills. Some Muslim women were taken captives and sold into sexual slavery.[14]

Acquisition of Ladakh

Through the conquest of Kishtwar, the Jammu state gained control of two of the roads which lead into Ladakh. Although there were huge difficulties due to the mountains and glaciers, Gulab Singh's Dogra troop under the command of general Zorawar Singh Kahluria conquered the whole of Buddhist Ladakh in two campaigns.[15] A few years later, in 1840, Zorawar Singh invaded Baltistan, captured the Raja of Skardu, who had sided with the Ladakhis, and annexed his country to Gulab Singh's kingdom. Thus, whether by policy or accident, Gulab Singh's dominions encircled Kashmir by 1840.[15]

Anglo-Sikh War

After the death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1839, the Sikh court fell into anarchy and palace intrigues took over. Gulab Singh's brothers Dhyan Singh and Suchet Singh as well as his nephew Hira Singh were murdered in the struggles. His eldest son, Udham Singh, also died in the process. Gulab Singh was careful to disassociate himself from the intrigues and focused on managing his Jagir and expanding his influence in the territories surrounding Kashmir.[16] Nevertheless, in early 1845, the Sikh Darbar marched on Jammu to seek the "reputed treasures" of Gulab Singh and demanded a fine of 30 million Nanakshahee rupees on the grounds that he had supported Hira Singh. But Gulab Singh used his battle skills as well as diplomacy to turn the Sikh troops in his favour and escaped with a payment of about 7 million rupees. He was however forced to surrender his second nephew Jawahir Singh, heir to Dhyan Singh, who was soon imprisoned by the Sikh Darbar.[17][18]

On the eve of the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845–1846), the relations between Gulab Singh and the Sikh Darbar were severely strained. Robert Huttenback states that Gulab Singh, as well as the British East India Company, had anticipated that the Sikh power would collapse after the death of Ranjit Singh and Gulab Singh positioned himself to become an independent ruler in due course.[19] He also maintained friendly relations with the East India Company and had no intention of jeopardising them for the sake of the anarchic Sikh Darbar. On the other hand, The Sikh army had no trust in any of the Sikh commanders in Lahore and asked for Gulab Singh to lead them. This, Gulab Singh refused to do. He counselled alliance with the British instead, and pursued his own communications with the British, seeking reassurance that his Jagirs would not be disturbed.[20]

When the Sikh campaign was going badly, Gulab Singh arrived in Lahore and he was installed as the Prime Minister on 31 January 1846. He continued his criticism of the war and opened negotiations with the British. His conduct as the Prime Minister of the Sikh Government was duplicitous and contributed to a Sikh defeat. [21] During the negotiations, the British were appreciative of Gulab Singh's non-involvement in the war and offered to make him an independent ruler along with Kashmir added to his domains. According to K. M. Panikkar, Gulab Singh refused the offer, stating that he was negotiating on behalf of the Sikhs and could not accept offers in his own interest.[22]

However, the British made their own arrangement by demanding from the Sikhs the territories between Sutlej and Beas and a war indemnity of 15 million Nanakshahee rupees. These were agreed to by Gulab Singh and the Sikh delegation, forming the basis for the Treaty of Lahore.[23]

Creation of Jammu and Kashmir

Following the agreement with the British, the Sikh Darbar accused Gulab Singh of duplicity and stripped him of the Prime Ministership. The new Prime Minister, Lal Singh, offered Gulab Singh's own territories to the British in lieu of the war indemnity, signalling a complete break with Gulab Singh. The British, however, demanded the entire hill territory between Beas and the Indus in lieu of the indemnity, which included the Kashmir Valley and Hazara in addition to Gulab Singh's dominions. This was agreed. Having accepted the territory, the British then transferred it to Gulab Singh in the Treaty of Amritsar a week later, in return for a payment of 7.5 million rupees (half the indemnity demanded from the Sikhs). The British as well as the Sikh Empire recognized him as an independent Maharaja.[24]

Lahore however instructed its governor of Kashmir, Sheikh Imam Uddin, to resist the hand-over of Kashmir. Gulab Singh's emissary Wazir Lakhpat was killed by the Sikh army in Kashmir. Gulab Singh also faced rebellions in the provinces of Rajouri and Rampur. Beset by all sides, Gulab Singh appealed to the British to implement its treaty obligations. Subsequently, a combined force from Lahore, the British and the Dogras arrived in Kashmir and acquired the surrender of Kashmir. Wazir Lal Singh of the Sikh Darbar was dismissed for inciting rebellions. Gulab Singh entered Srinagar on 9 November 1846 as the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir.[25][26]

Territorial adjustments

Following a rebellion in Hazara, Gulab Singh asked for an exchange of Hazara for other territories. Consequently, Hazara was transferred back to Lahore and Gulab Singh received Kathua and Suchetgarh and part of Minawar in exchange. In 1847, Sujanpur and part of Pathankot were handed over to the British in lieu of pensions to disinherited hill chiefs.[27]

The sons of Dhyan Singh, Jawahir Singh and Moti Singh, put forward a claim to Poonch, on the grounds that it was the Jagir of their father, and to Jasrota, which was earlier a Jagir of their brother Hira Singh. After negotiation, the British granted them Chalayar and Watala as Jagirs with the title of Raja. They were to give the Maharaja Gulab Singh a horse with gold trappings every year and consult him on matters of importance. In 1852, Poonch was granted to Moti Singh as a Jagir on the same conditions.[28]

The Raja of the Chamba State (which became part of Gulab Singh's territories by the Treaty of Amritsar) put forward a claim that Bhadarwah was a Jagir granted to him by the Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Since the situation was anomalous, the British let Bhadarwah be retained by Gulab Singh but allowed Chamba to be separated in a subsidiary alliance with the British Government.[29]

The settlement of the boundary between Ladakh and Tibet was carried out by Alexander Cunningham with the assistance of Henry Strachey and Dr. Thomson in 1847. Thus the present borders of Jammu and Kashmir were finalised.[30]

Gilgit

Not long afterwards the Rajah of Hunza attacked Gilgit and defeated Gulab Singh's forces under the command of Nathu Shah. Gilgit fort was occupied by the Rajah of Hunza, along with Punial, Yasin, and Darel. Gulab Singh then sent two columns, one from Astore and one from Baltistan, which recovered Gilgit after some fighting. However, in 1852, the Dogras at Gilgit were annihilated by Gaur Rahman of Yasin, and for eight years, the Indus River formed the northern boundary of the Maharaja's territories.[31]

After Gulab Singh's death 1857, his successor, Ranbir Singh, loyally sided with the British in the Indian Rebellion of 1857. When Kashmir had recovered from the strain of the Rebellion, Ranbir Singh proceeded to recover Gilgit and to expand the frontier. In 1860 a force under Devi Singh crossed the Indus, and advanced on Gaur Rahman's fortress at Gilgit. Gaur Rahman had died just before the arrival of the Dogras, and Gilgit was taken.[31] Gilgit was not the last frontier, however. [32]Ranbir attempted to conquer Yasin and Punial, but failed due to lack of funds. Gilgit and Astore were nevertheless acquired and remained under the Dogra control until the partition of India in 1947, although the territory was leased to the British in later years.[33]

Ranbir Singh, although tolerant of other creeds, lacked his father's strong will and determination, and his control over the State officials was weak. The later part of his life was darkened by the dreadful famine in Kashmir, 1877–1879. In September 1885, he was succeeded by his eldest son, Pratap Singh.[31]

Pratap Singh defeated the ruler of Chitral in 1891, and forced Hunza and Nagar to accept the suzerainty of Kashmir and Jammu state.[34]

Rulers

| S.no | Name | Reign |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Gulab Singh | 1846–1857 |

| 2. | Ranbir Singh | 1857–1885 |

| 3. | Pratap Singh | 1885–1925 |

| 4. | Hari Singh | 1925–1948 |

| 5. | Karan Singh (Prince Regent) | 1948–1952 |

Administration

According to the census reports of 1911, 1921 and 1931, the administration was organised as follows:[35][36]

- Jammu province: Districts of Jammu, Jasrota (Kathua), Udhampur, Reasi and Mirpur.

- Kashmir province: Districts of Kashmir South (Anantnag), Kashmir North (Baramulla) and Muzaffarabad.

- Frontier districts: Wazarats of Ladakh and Gilgit.

- Internal jagirs: Poonch, Bhaderwah and Chenani.

In the 1941 census, further details of the frontier districts were given:[35]

- Ladakh wazarat: Tehsils of Leh, Skardu and Kargil.

- Gilgit wazarat: Tehsils of Gilgit and Astore

- Frontier illaqas: Punial, Ishkoman, Yasin, Kuh-Ghizer, Hunza, Nagar, Chilas.

Prime Ministers

| # | Name | Took Office | Left Office |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Raja Hari Singh | 1925 | 1927 |

| 2 | Sir Albion Banerjee | January, 1927 | March, 1929 |

| 3 | G. E. C. Wakefield | 1929 | 1931 |

| 4 | Hari Krishan Kaul[37] | 1931 | 1932 |

| 5 | Elliot James Dowell Colvin[37] | 1932 | 1936 |

| 6 | Sir Barjor J. Dalal | 1936 | 1936 |

| 7 | Sir N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar | 1936 | July, 1943 |

| 8 | Kailash Narain Haksar | July, 1943 | February, 1944 |

| 9 | Sir B. N. Rau | February, 1944 | 28 June 1945 |

| 10 | Ram Chandra Kak | 28 June 1945 | 11 August 1947 |

| 11 | Janak Singh | 11 August 1947 | 15 October 1947 |

| 12 | Mehr Chand Mahajan | 15 October 1947 | 5 March 1948 |

| 13 | Sheikh Abdullah | 5 March 1948 | 9 August 1953 |

Geography

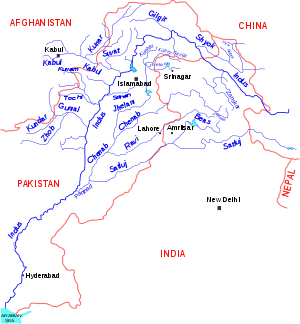

The area of the state extended from 32° 17' to 36° 58' N and from 73° 26' to 80° 30' E.[38] Jammu was the southernmost part of the state and was adjacent to the Punjab districts of Jhelum, Gujrat, Sialkot, and Gurdaspur. There is a fringe of level land along the Punjab frontier, bordered by a plinth of low hilly country sparsely wooded, broken, and irregular. This is known as the Kandi, the home of the Chibs and the Dogras. To travel north, a range of mountains 8,000 feet (2,400 m) high must be climbed.

This is a temperate country with forests of oak, rhododendron, chestnut, and higher up, of deodar and pine, a country of uplands, such as Bhadarwah and Kishtwar, drained by the deep gorge of the Chenab river. The steps of the Himalayan range, known as the Pir Panjal, lead to the second story, on which rests the valley of Kashmir, drained by the Jhelum river.[38]

Steeper parts of the Himalayas lead to Astore and Baltistan on the north and to Ladakh on the east, a tract drained by the river Indus. To the northwest, lies Gilgit, west and north of the Indus. The whole area is shadowed by a wall of giant mountains that run east from the Kilik or Mintaka passes of the Hindu Kush, leading to the Pamirs and the Chinese dominions past Rakaposhi (25,561 ft), along the Muztagh range past K2 (Godwin-Austen Glacier, 28,265 feet), Gasherbrum and Masherbrum (28,100 and 28,561 feet (8,705 m) respectively) to the Karakoram range which merges in the Kunlun Mountains. Westward of the northern angle above Hunza and Nagar, the maze of mountains and glaciers trends a little south of east along the Hindu Kush range bordering Chitral and so on into the limits of Kafiristan and Afghan territory.[38]

Transport

There used to be a route from Kohala to Leh; it was possible to travel from Rawalpindi via Kohala and over the Kohala Bridge into Kashmir. The route from Kohala to Srinagar was a cart-road 132 miles (212 km) in length. From Kohala to Baramulla the road was close to the River Jhelum. At Muzaffarabad the Kishenganga River joins the Jhelum and at this point the road from Abbottabad and Garhi Habibullah meet the Kashmir route. The road carried heavy traffic and required expensive maintenance by the authorities to repair.[39]

Flooding

In 1893, after 52 hours of continuous rain, very serious flooding took place in the Jhelum valley and much damage was done to Srinagar. The floods of 1903 were much more severe, a great disaster.[40]

Demographics

The state of Jammu and Kashmir combined disparate regions, religions, and ethnicities.[41] In the British census of India of 1941, Jammu and Kashmir registered a Muslim majority population of 77%, a Hindu population of 20% and a sparse population of Buddhists and Sikhs comprising the remaining 3%.[42] The total Muslim population in the State was over 31 lacs (3,100,000).[43]

The 1941 Census reported that most of the Muslims in the Jammu Province and its Jagirs were closely connected with the tribes of the Punjab and were of the same original stock as the Hindu elements of Jammu's population; with the Gujjars being an important element. Among Jammu Province's population the ethnic makeup was composed of Arains, Jats, Sudhans, Gujjars and Rajputs etc.[44]

The Muslims living in the southern part of the Kashmir Province (Baramulla and Anantnag districts) were of the same stock as the Kashmiri Pandit community and were designated as Kashmiri Muslims. The population of the Muzaffarabad District was partly Kashmiri Muslim, partly Gujjar and the rest were of the same stock as the tribes of the neighbouring Punjab and North West Frontier Province (NWFP). The 1921 Census report stated that Kashmiri Muslims were sub-divided into numerous sub-castes such as Bat, Dar, Wain etc.[45] The 1921 Census report stated that Kashmiri Muslims formed 31% of the Muslim population of the entire princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.[46]

The Muslims of the Ladakh District were mostly Mongolian (Baltis) by race. In Astore and the various illaqas of the Gilgit Agency the population mostly consisted of Dards.[43]

Muslims in the Kashmir Valley are predominantly Sunni, as is the case among Jammu's Muslims. However, nearly all Muslims in Ladakh are Shia.[47]

End of the princely state

In 1947, Britain gave up its rule of India. The Indian Independence Act divided British India into two independent states, the Dominion of Pakistan and Dominion of India. According to the Act, "the suzerainty of His Majesty over the Indian States lapses, and with it, all treaties and agreements in force at the date of the passing of this Act between His Majesty and the rulers of Indian States."[48] So each of the princely states was now free to join India or Pakistan or to remain independent. Most of the princes acceded to one or the other of the two nations.

Maharaja Hari Singh wanted his state to remain independent, joining neither Pakistan nor India but maintaining friendly relations with both. For this reason, he offered a standstill agreement to both the countries. Pakistan immediately accepted the offer, even though no actual agreement was ever executed. India requested a representative to be sent for discussions.[34][49] At any event, the agreement with Pakistan soon came unstuck as Pakistan imposed an economic blockade on the state in early September, stopping essential supplies and trade in timber and produce, resulting in heated exchanges between the two governments. The state turned to India for help, which started air-lifting essential items like salt and kerosene.[50]

The Maharaja also faced a rebellion in Poonch and Pakistan started arming the rebels. On 22 October, it launched a full-blown invasion of the state using Pashtun tribes with an intent to take the capital Srinagar. Unable to withstand the invasion, the Maharaja requested India for military assistance. India agreed to airlift troops under three conditions:

- The Maharaja must accede to India.

- He should democratise the internal administration of the state and frame a new constitution along the Mysore model.

- He should take the National Conference leader Sheikh Abdullah into government and make him responsible for it along with the prime minister.[51]

The Maharaja accepted the conditions and signed the Instrument of Accession in favour of India on 26–27 October. Sheikh Abdullah was appointed as the Head of Emergency Administration to run the affairs in Kashmir while the Maharaja himself withdrew to Jammu.

The Instrument was accepted by the Governor-General the next day, 27 October. With the signature of the Maharaja and the acceptance by the Governor-General, the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir became a part of the Dominion of India. Indian troops landed at Srinagar airport in Kashmir on 27 October and secured the airport before proceeding to evict the invaders from the Kashmir Valley.

The princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, thus came under Indian suzerainty on 27 October 1947, with the western and northern portions (Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan) having passed to Pakistan's control. Later in 1948, The Maharaja appointed Sheikh Abdullah as the Prime Minister and his son Karan Singh as the Prince Regent to act on his behalf. Jammu and Kashmir operated as a princely state under Indian control until 1952.

After the Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir was elected in 1952, it passed a resolution supporting the abolition of monarchy. Via the 1952 Delhi Agreement, the Government of India conceded the wishes of the state's people and the monarchy was abolished. Prince Karan Singh then accepted the post of Sadar-i-Riyasat (constitutional Head of State).[52][53][54]

See also

References

- ↑ Jerath, Ashok (1998). Dogra Legends of Art and Culture, p. 22

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 111–125.

- ↑ Mehr Chand Mahajan (1963). Looking Back. Bombay: Asia Publishing House. p. 162. ISBN 978-81-241-0194-0.

- ↑ "Q&A: Kashmir dispute - BBC News".

- ↑ Bose, Sumantra (2003). Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace. Harvard University Press. pp. 32–37. ISBN 0-674-01173-2.

- ↑ Jeratha, Dogra Legends of Art & Culture 1998, p. 187.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 10.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 10–12.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 15–16.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, pp. 14-34.

- ↑ Huttenback, Gulab Singh and the Creation of the Dogra State 1961, p. 478.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 37.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, pp. 40-41.

- ↑ Hastings Donnan, Marriage Among Muslims: Preference and Choice in Northern Pakistan, (Brill, 1997), 41.

- 1 2 "Kashmir and Jammu" Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 15, p. 95.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, Chapters III, IV.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, pp. 65-72.

- ↑ Satinder Singh, Raja Gulab Singh's Role 1971, p. 37.

- ↑ Huttenback, Gulab Singh and the Creation of the Dogra State 1961, p. 479.

- ↑ Satinder Singh, Raja Gulab Singh's Role 1971, pp. 39-43.

- ↑ Satinder Singh, Raja Gulab Singh's Role 1971, pp. 46-50.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, pp. 96-97.

- ↑ Satinder Singh, Raja Gulab Singh's Role 1971, pp. 51-52.

- ↑ Satinder Singh, Raja Gulab Singh's Role 1971, pp. 52-53.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, pp. 118-119.

- ↑ Major, Return to Empire 1981, pp. 135-137.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, pp. 119-120.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, pp. 121-123.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 124.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, pp. 120-121.

- 1 2 3 "Kashmir and Jammu". Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 15, p. 96.

- ↑ "The DOGRA Rule". krishnamehta.net. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- ↑ Amar Singh Chohan (1997). Gilgit Agency 1877-1935. Atlantic Publishers & Dist.

- 1 2 Victoria Schofield (2000). Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan, and the Unending War. I. B. Tauris.

- 1 2 Karim, Maj Gen Afsir (2013), Kashmir The Troubled Frontiers, Lancer Publishers LLC, pp. 29–32, ISBN 978-1-935501-76-3

- ↑ Behera, Demystifying Kashmir 2007, p. 15.

- 1 2 Copland, Ian (1981), "Islam and Political Mobilization in Kashmir, 1931-34", Pacific Affairs, 54 (2): 228–259, JSTOR 2757363

- 1 2 3 "Kashmir and Jammu" Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 15, p. 72.

- ↑ "Kashmir and Jammu" Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 15, p. 79.

- ↑ "Kashmir and Jammu" Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 15, p. 89

- ↑ Bowers, Paul. 2004. "Kashmir". Research Paper 4/28, International Affairs and Defence, House of Commons Library, United Kingdom. Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Bose, Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace 2003, pp. 15–17

- 1 2 Census of India, 1941. VOLUME XXII. p. 9.

- ↑ Anant, Ram; Raina, Hira Nand (1933). Census of India, 1931. Vol. XXIV: Jammu and Kashmir State. Part I: Report. p. 316. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

Kashmiri Muslim.-The community occupies the fore-most position in the State having 1,352,822 members. The various sub-castes that are labelled under the general head Kashmiri Muslim are given in the Imperial Table. The most important sub-castes from the statistical point of view are the Bat, the Dar, the Ganai, the Khan, the Lon, the Malik, the Mir, the Pare, the Rather, Shah, Sheikh and Wain. They are mostly found in the Kashmir Province and Udhampur district of the Jammu Province.

- ↑ Mohamed, C K. Census of India, 1921. Vol. XXII: Kashmir. Part I: Report. p. 150. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

The Kashmiri Musalmans are sub-divided into numerous sub-castes such as Dar, Bat, Wain, etc.

- ↑ Mohamed, C K. Census of India, 1921. Vol. XXII: Kashmir. Part I: Report. p. 147. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

The bulk of the population in Group I is furnished by the Kashmiri Musalmans (796,804), who form more than 31 per cent of the total Musalman population of the State. The Kashmiri Musalman is essentially an agriculturist by profession, but his contribution to the trade and industry of the Kashmir Province is by no means negligible.

- ↑ Christopher Snedden (2015). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Oxford University Press. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-1-84904-342-7.

- ↑ Indian Independence Act 1947 (c.30) Archived 15 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Revised Statute from the UK Statute Law Database

- ↑ Birdwood, Two Nations and Kashmir 1956, pp. 45.

- ↑ Birdwood, Two Nations and Kashmir 1956, pp. 46.

- ↑ Mahajan, Looking Back 1963, p. 155.

- ↑ Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India (2010), pp. 221–222.

- ↑ Das Gupta, Jammu and Kashmir (2012), pp. 185, 196–200.

- ↑ Noorani, Article 370 (2011), pp. 8–9.

Bibliography

- Behera, Navnita Chadha (2007), Demystifying Kashmir, Pearson Education India, ISBN 8131708462

- Das Gupta, Jyoti Bhusan (2012), Jammu and Kashmir, Springer, ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6

- Birdwood, Lord (1956), Two Nations and Kashmir, R. Hale

- Huttenback, Robert A. (1961), "Gulab Singh and the Creation of the Dogra State of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh" (PDF), The Journal of Asian Studies, 20 (4): 477–488, doi:10.2307/2049956, archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2016

- Mahajan, Mehr Chand (1963), Looking Back: The Autobiography of Mehr Chand Mahajan, Former Chief Justice of India, Asia Publishing House

- Major, Andrew J. (1996), Return to Empire: Punjab under the Sikhs and British in the Mid-nineteenth Century Limited, New Delhi: Sterling Publishers, ISBN 81-207-1806-2

- Major, Andrew J. (1981), Return to Empire: Punjab under the Sikhs and British in the Mid-nineteenth Century, Australian National University

- Noorani, A. G. (2011), Article 370: A Constitutional History of Jammu and Kashmir, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-807408-3, (Subscription required (help))

- Panikkar, K. M. (1930). Gulab Singh. London: Martin Hopkinson Ltd.

- Raghavan, Srinath (2010), War and Peace in Modern India, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 101–, ISBN 978-1-137-00737-7

- Rai, Mridu (2004), Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir, C. Hurst & Co, ISBN 1850656614

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, ISBN 1860648983

- Singh, Bawa Satinder (1971), "Raja Gulab Singh's Role in the First Anglo-Sikh War", Modern Asian Studies, 5 (1): 35–59, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00002845, JSTOR 311654

This article incorporates text from the Imperial Gazetteer of India, a publication now in the public domain.