Gilgit

Gilgit

| |

|---|---|

| City | |

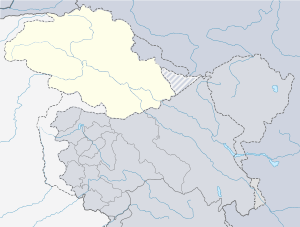

Gilgit is located in a broad valley | |

| Nickname(s): Gleet | |

Gilgit  Gilgit | |

| Coordinates: 35°55′15″N 74°18′30″E / 35.92083°N 74.30833°ECoordinates: 35°55′15″N 74°18′30″E / 35.92083°N 74.30833°E | |

| Country |

|

| Autonomous state |

|

| District | Gilgit District |

| First mention | 3rd Century BC |

| Area | |

| • Total | 57 km2 (22 sq mi) |

| Elevation[1] | 1,500 m (4,900 ft) |

| Population (1998) | |

| • Total | 216,760 |

| • Density | 3,800/km2 (9,800/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Urdu, Shina[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PST) |

| PIN | 1571 – 1xx[3] |

| Area code(s) | +943 |

| Website |

gilgit |

Gilgit (Shina: گلیت, Urdu: گلگت), known locally as Gileet, is the capital city of the Gilgit-Baltistan region, an administrative territory of Pakistan. The city is located in a broad valley near the confluence of the Gilgit River and Hunza River. Gilgit is a major tourist destination in northern Pakistan, and serves as a hub for mountaineering expeditions in the Karakoram Range. It was an important stop on the ancient Silk Road, and today serves as a major junction along the Karakoram Highway with road connections to China, Skardu, Chitral, Peshawar, and Islamabad.

Etymology

The city's ancient name was Sargin, later to be known as Gilit, and it is still referred to as Gilit or Sargin-Gilit by local people. In the Burushaski language, it is named Geelt and in Wakhi and Khowar it is called Gilt.

History

Early history

Brogpas trace their settlement from Gilgit into the fertile villages of Ladakh through a rich corpus of hymns, songs, and folklore that have been passed down through generations.[4] The Dards and Shinas appear in many of the old Pauranic lists of people who lived in the region, with the former also mentioned in Ptolemy's accounts[5] of the region.

Buddhist era

Gilgit was an important city on the Silk Road, along which Buddhism was spread from South Asia to the rest of Asia. It is considered as a Buddhism corridor from which many Chinese monks came to Kashmir to learn and preach Buddhism.[6] Two famous Chinese Buddhist pilgrims, Faxian and Xuanzang, traversed Gilgit according to their accounts.

According to Chinese records, between the 600s and the 700s, the city was governed by a Buddhist dynasty referred to as Little Balur or Lesser Bolü (Chinese: 小勃律).[7] They are believed to be the Patola Sahi dynasty mentioned in a Brahmi inscription,[8] and are devout adherents of Vajrayana Buddhism.[9]

In mid-600s, Gilgit came under Chinese suzerainty after the fall of Western Turkic Khaganate due to Tang military campaigns in the region. In late 600s CE, the rising Tibetan Empire wrestled control of the region from the Chinese. However, faced with growing influence of the Umayyad Caliphate and then the Abbasid Caliphate to the west, the Tibetans were forced to ally themselves with the Islamic caliphates. The region was then contested by Chinese and Tibetan forces, and their respective vassal states, until the mid-700s. Chinese record of the region last until late-700s at which time the Tang's western military campaign was weakened due to the An Lushan Rebellion.[10]

The control of the region was left to the Tibetan Empire. They referred to the region as Bruzha, a toponym that is consistent with the ethnonym "Burusho" used today. Tibetan control of the region lasted until late-800s CE.[11]

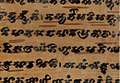

Gilgit manuscripts

This corpus of manuscripts was discovered in 1931 in Gilgit, containing many Buddhist texts such as four sutras from the Buddhist canon, including the famous Lotus Sutra. The manuscripts were written on birch bark in the Buddhist form of Sanskrit in the Sharada script. They cover a wide range of themes such as iconometry, folk tales, philosophy, medicine and several related areas of life and general knowledge.[12]

The Gilgit manuscripts[13] are included in the UNESCO Memory of the World register.[14] They are among the oldest manuscripts in the world, and the oldest manuscript collection surviving in Pakistan,[13] having major significance in the areas of Buddhist studies and the evolution of Asian and Sanskrit literature. The manuscripts are believed to have been written in the 5th to 6th centuries AD, though some more manuscripts were discovered in the succeeding centuries, which were also classified as Gilgit manuscripts.

As of 6 October 2014, one source claims that the part of the collection deposited at the Sri Pratap Singh Museum in Srinagar was irrecoverably destroyed during the 2014 India–Pakistan floods.[15]

Pre-Trakhàn

| “ | The former rulers had the title of Ra, and there is a reason to suppose that they were at one time Hindus, but for the last five centuries and a half they have been Moslems. The names of the Hindu Ras have been lost, with the exception of the last of their number, Shri Ba'dut. Tradition relates that he was killed by a Mohammedan adventurer, who married his daughter and founded a new dynasty, since called Trakhàn, from a celebrated Ra named Trakhan, who reigned about the commencement of the fourteenth century. The previous rulers—of whom Shri Ba'dut was the last—were called Shahreis.[16] | ” |

Trakhàn Dynasty

Gilgit was ruled for centuries by the local Trakhàn Dynasty, which ended about 1810 with the death of Raja Abas, the last Trakhàn Raja.[6] The rulers of Hunza and Nager also claim origin with the Trakhàn dynasty. They claim descent from a heroic Kayani Prince of Persia, Azur Jamshid (also known as Shamsher), who secretly married the daughter of the king Shri Badat.

She conspired with him to overthrow her cannibal father. Sri Badat's faith is theorised as Hindu by some[17][18] and Buddhist by others.[19][20] However, considering the region's Buddhist heritage, with the most recent influence being Islam, the most likely preceding influence of the region is Buddhism.

Prince Azur Jamshid succeeded in overthrowing King Badat who was known as the Adam Khor (literally "man-eater"),[21][22] often demanding a child a day from his subjects, his demise is still celebrated to this very day by locals in traditional annual celebrations.[23] In the beginning of the new year, where a Juniper procession walks along the river, in memory of chasing the cannibal king Sri Badat away.[24]

Azur Jamshid abdicated after 16 years of rule in favour of his wife Nur Bakht Khatùn until their son and heir Garg, grew of age and assumed the title of Raja and ruled, for 55 years. The dynasty flourished under the name of the Kayani dynasty until 1421 when Raja Torra Khan assumed rulership. He ruled as a memorable king until 1475. He distinguished his family line from his stepbrother Shah Rais Khan (who fled to the king of Badakshan, and with whose help he gained Chitral from Raja Torra Khan), as the now-known dynastic name of Trakhàn. The descendants of Shah Rais Khan were known as the Ra'issiya Dynasty.[25]

1800s

| “ | The period of greatest prosperity was probably under the Shin Ras, whose rule seems to have been peaceable and settled. The whole population, from the Ra to the poorest subject lived by agriculture. According to tradition, Shri Buddutt's rule extended over Chitral, Yassin, Tangir, Darel, Chilas, Gor, Astor, Hunza, Nagar and Haramosh all of which were held by tributary princes of the same family.[16] | ” |

The area had been a flourishing tract but prosperity was destroyed by warfare over the next fifty years, and by the great flood of 1841 in which the river Indus was blocked by a landslip below the Hatu Pir and the valley was turned into a lake.[26] After the death of Abas, Sulaiman Shah, Raja of Yasin, conquered Gilgit. Then, Azad Khan the cheater, Raja of Punial, killed Sulaiman Shah, taking Gilgit; then Tahir Shah, Raja of Buroshall (Nagar), took Gilgit and killed Azad Khan.

Tair Shah's son Shah Sakandar inherited, only to be killed by Gohar Aman, Raja of Yasin of the Khushwakhte Dynasty when he took Gilgit. Then in 1842, Shah Sakandar's brother, Karim Khan, expelled Yasin rulers with the support of a Sikh army from Kashmir. The Sikh general, Nathu Shah, left garrison troops and Karim Khan ruled until Gilgit was ceded to Gulab Singh of Jammu and Kashmir in 1846 by the Treaty of Amritsar,[6] and Dogra troops replaced the Sikh in Gilgit.

Nathu Shah and Karim Khan both transferred their allegiance to Gulab Singh, continuing local administration. When Hunza attacked in 1848, both of them were killed. Gilgit fell to the Hunza and their Yasin and Punial allies but was soon reconquered by Gulab Singh's Dogra troops. With the support of Raja Gohar Aman, Gilgit's inhabitants drove their new rulers out in an uprising in 1852. Raja Gohar Aman then ruled Gilgit until his death in 1860, just before new Dogra forces from Ranbir Singh, son of Gulab Singh, captured the fort and town.[6]

In the 1870s Chitral was threatened by Afghans, Maharaja Ranbir Singh was firm in protecting Chitral from Afghans, the Mehtar of Chitral asked for help. In 1876 Chitral accepted the authority of Jammu Clan and in reverse get the protection from the Dogras who have in the past took part in many victories over Afghans during the time of Gulab Singh Dogra.[27]

British Raj

In 1877, in order to guard against the advance of Russia, the British India Government, acting as the suzerain power of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, established the Gilgit Agency. The Agency was re-established under control of the British Resident in Jammu and Kashmir. It comprised the Gilgit Wazarat; the State of Hunza and Nagar; the Punial Jagir; the Governorships of Yasin, Kuh-Ghizr and Ishkoman, and Chilas.

The Tajiks of Xinjiang sometimes enslaved the Gilgiti and Kunjuti Hunza.[28]

In 1935, the British India government demanded from the Jammu and Kashmir state to lease them Gilgit town plus most of the Gilgit Agency and the hill-states Hunza, Nagar, Yasin and Ishkoman for 60 years.[29] The leased region was then treated as part of British India, administered by a Political Agent at Gilgit responsible to Delhi, first through the Resident in Jammu and Kashmir and later a British Agent in Peshawar.

Jammu and Kashmir State no longer kept troops in Gilgit and a mercenary force, the Gilgit Scouts, was recruited with British officers and paid for by Delhi. In April 1947, Delhi decided to formally retrocede the leased areas to Hari Singh’s Jammu and Kashmir State as of 15 August 1947. The transfer was to formally take place on 1 August. However, the Gilgit Scouts rebelled against this action, and under the guidance of Major WA 'Willie' Brown, ceded to the newly founded state of Pakistan.

Abdullah Sahib was an Arain and belonged to Chimkor Sahib village of Ambala district Punjab, British India. Abdullah Sahib was the first Muslim governor of the Gilgit in British time period and was close associate of Maharaja Partap Singh.[30]

Khan Bahadur Kalay Khan, a Mohammed Zai Pathan, was the Governor of Gilgit Hunza and Kashmir before partition.

1947 Kashmir war

On 26 October 1947, Maharaja Hari Singh of Jammu and Kashmir, faced with a tribal invasion by Pakistan, signed the Instrument of Accession, joining India.

Gilgit's population did not favour the State's accession to India.[31] The Muslims of the Frontier Districts Province (modern day Gilgit-Baltistan) had wanted to join Pakistan.[32] Sensing their discontent, Major William Brown, the Maharaja's commander of the Gilgit Scouts, mutinied on 1 November 1947, overthrowing the Governor Ghansara Singh. The bloodless coup d'etat was planned by Brown to the last detail under the code name "Datta Khel", which was also joined by a rebellious section of the Jammu and Kashmir 6th Infantry under Mirza Hassan Khan. Brown ensured that the treasury was secured and minorities were protected. A provisional government (Aburi Hakoomat) was established by the Gilgit locals with Raja Shah Rais Khan as the president and Mirza Hassan Khan as the commander-in-chief. However, Major Brown had already telegraphed Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan asking Pakistan to take over. The Pakistani political agent, Khan Mohammad Alam Khan, arrived on 16 November and took over the administration of Gilgit.[33][34] Brown outmaneuvered the pro-Independence group and secured the approval of the mirs and rajas for accession to Pakistan. Browns's actions surprised the British Government.[35]

The provisional government lasted 16 days. The provisional government lacked sway over the population. The Gilgit rebellion did not have civilian involvement and was solely the work of military leaders, not all of whom had been in favor of joining Pakistan, at least in the short term. Historian Ahmed Hasan Dani mentions that although there was lack of public participation in the rebellion, pro-Pakistan sentiments were intense in the civilian population and their anti-Kashmiri sentiments were also clear.[36] According to various scholars, the people of Gilgit as well as those of Chilas, Koh Ghizr, Ishkoman, Yasin, Punial, Hunza and Nagar joined Pakistan by choice.[37][38][39][40][41]

Demographics

About 100% of the population of Gilgit is Muslim, with 70% being Twelver Shia Muslims, 12% being Ismaili Shia Muslims and 18% being Sunni Muslims.[42]

Geography

Gilgit is situated in a valley formed by the confluence of the Indus River, Hunza River and Gilgit River.

Climate

Gilgit experiences a cold desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWk). Weather conditions for Gilgit are dominated by its geographical location, a valley in a mountainous area, southwest of Karakoram range. The prevalent season of Gilgit is winter, occupying the valley eight to nine months a year.

Gilgit lacks significant rainfall, averaging in 120 to 240 millimetres (4.7 to 9.4 in) annually, as monsoon breaks against the southern range of Himalayas. Irrigation for land cultivation is obtained from the rivers, abundant with melting snow water from higher altitudes.

The summer season is brief and hot. Strong sunshine occasionally raises temperaturs to 40 °C (104 °F), though it typically is cooler in the shade. As a result of this extremity in the weather, landslides and avalanches are frequent in the area.[43]

| Climate data for Gilgit | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.5 (63.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

29.4 (84.9) |

37.2 (99) |

41.5 (106.7) |

43.5 (110.3) |

46.3 (115.3) |

43.8 (110.8) |

41.6 (106.9) |

36.0 (96.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

24.5 (76.1) |

46.3 (115.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.6 (49.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

29.0 (84.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

36.2 (97.2) |

35.3 (95.5) |

31.8 (89.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

11.6 (52.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.7 (27.1) |

0.4 (32.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

6.3 (43.3) |

0.4 (32.7) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.0 (14) |

−8.9 (16) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

1.1 (34) |

3.9 (39) |

5.1 (41.2) |

10.0 (50) |

9.8 (49.6) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−11.1 (12) |

−11.1 (12) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 4.6 (0.181) |

6.7 (0.264) |

11.8 (0.465) |

24.4 (0.961) |

25.1 (0.988) |

8.9 (0.35) |

14.6 (0.575) |

14.9 (0.587) |

8.1 (0.319) |

6.3 (0.248) |

2.4 (0.094) |

5.1 (0.201) |

107.8 (4.244) |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:00 PST) | 51.3 | 34.6 | 26.7 | 27.6 | 26.6 | 23.7 | 29.8 | 36.8 | 36.7 | 42.2 | 49.1 | 55.0 | 36.7 |

| Source: Pakistan Meteorological Department[44] | |||||||||||||

Administration

The city of Gilgit constitutes a tehsil within Gilgit District.[45]

Tourism

Gilgit city is one of the two major hubs for all mountaineering expeditions in Gilgit-Baltistan. Almost all tourists headed for treks in Karakoram or Himalaya Ranges depart from Gilgit

Attractions

There are several tourist attractions relatively close to Gilgit: Naltar Valley with Naltar Peak, Hunza Valley, Nagar Valley, Fairy Meadow in Raikot, Shigar town, Skardu Valley, Haramosh Valley in Karakoram Range, Bagrot Valley, Deosai National Park in Skardu, Astore Valley, Phunder village, Ghizer Valley, The Land Of Lakes, Yasin Valley, Thoi Valley, Kargah Valley and Nomal Valley.

Transportation

Air

Gilgit is served by the nearby Gilgit Airport, with direct flights to Islamabad.

Road

Gilgit is located approximately 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from the Karakoram Highway (KKH). The roadway is being upgraded as part of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor. The KKH connects Gilgit to Chilas, Dasu, Besham, Mansehra, Abbottabad and Islamabad in the south. Gilgit is connected to Karimabad (Hunza) and Sust in the north, with further connections to the Chinese cities of Tashkurgan, Upal and Kashgar in Xinjiang. Gilgit is also linked to Chitral in the west, and Skardu to the east. The road to Skardu will be upgraded to a 4-lane road at a cost of $475 million.[46]

Transport companies such as the Silk Route Transport Pvt, Masherbrum Transport Pvt and Northern Areas Transport Corporation (NATCO), offer passenger road transport between Islamabad, Gilgit, Sust, and Kashgar and Tashkurgan in China.

The Astore-Burzil Pass Road, linking Gilgit to Srinagar was closed in 1978.[47]

Rail

Gilgit is not served by any rail connections. Long-term plans for the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor call for construction of the 682 kilometre long Khunjerab Railway, which is expected to be completed in 2030,[48] that would also serve Gilgit.

Education

- Karakoram International University Gilgit

- Public Schools and Colleges Jutial Gilgit

- Aga Khan Higher Secondary School Gilgit

- Army Public School and College Jutial Gilgit

- Al Mustafa Public School and College Majini Muhallah Gilgit

- Al Karim Model School Normal Gilgit

- Sir Syed public school and college kashrote Gilgit

Media

The Media of Gilgit is evolving as Gilgit Baltistan becomes a separate province of Pakistan so it is an important to have a growing media in the city Gilgit. There are number of newspapers in Gilgit Baltistan Daily Mahasib, daily Domel, Daily Shamal, K2 etc.

Health care

Gilgit city has following healthcare facilities

- DHQ Hospital Gilgit

- CMH Gilgit

- Aga Khan Medical Centre, Gilgit

Sister cities

Gallery

Danyor Tunnel Gilgit

Danyor Tunnel Gilgit- Danyor Tunnel

Manuscript of the Buddhist Jyotiṣkāvadāna text written in the early Sharada script, from Gilgit.

Manuscript of the Buddhist Jyotiṣkāvadāna text written in the early Sharada script, from Gilgit.- Night view of Gilgit. Photo by tnxl.huxain

Chinar Bagh Bridge

Chinar Bagh Bridge Broken Bridge at Jutial Gilgit

Broken Bridge at Jutial Gilgit

See also

References

- ↑ "Geography of Chitral". Chitralnews.com. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ "INDO-IRANIAN FRONTIER LANGUAGES". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 15 November 2006. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ "Post Codes". Pakistan Post Office. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ Counterinsurgency, Democracy and the Politics of Identity in Pakistan

- ↑ Counterinsurgency, Democracy and the Politics of Identity in India

- 1 2 3 4 Frederick Drew (1875) The Jummoo and Kashmir Territories: A Geographical Account E. Stanford, London, OCLC 1581591

- ↑ Sen, Tansen (2015). "Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of India–China Relations, 600–1400". Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442254732. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- ↑ Schmidt, Ruth Laila; Kohistani, Razwal (2008). A Grammar of the Shina Language of Indus Kohistan. Google Books. ISBN 3447056762. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- ↑ Twist, Rebecca L. (2007). "Patronage, Devotion and Politics: A Buddhological Study of the Patola Sahi Dynasty's Visual Record". Ohio State University. ISBN 9783639151718. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- ↑ Stein, Mark Aurel (1907). Ancient Khotan: Detailed Report of Archaeological Explorations in Chinese Turkestan. vol. 1. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. pp. 4–18.

- ↑ Mock, John (October 2013). "A Tibetan Toponym from Afghanistan" (PDF). Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines. Centre national de la recherche scientifique (27): 5–9. ISSN 1768-2959. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ↑ "BBC News – India: Rare Buddhist manuscript Lotus Sutra released". Bbc.co.uk. 3 May 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- 1 2 Gyan Marwah (August 2004). "Gilgit Manuscript — Piecing Together Fragments of History". The South Asian Magazine. Haryana, India. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ↑ "Gilgit Manuscript | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- ↑ "Kashmir floods damage 2000-year-old Buddhist treasures". http://www.dnaindia.com. 3 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014. External link in

|publisher=(help) - 1 2 John Bidduph (2004) Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh, Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN 1402152728, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Amar Singh Chohan (1984) The Gilgit Agency, 1877–1935, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, p. 4

- ↑ Reginald Charles (1976) Between the Oxus and the Indus, Francis Schomberg, p. 249

- ↑ Henry Osmaston, Philip Denwood (1995) Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5: Proceedings of the Fourth and Fifth, Motilal Banarsidass, p. 226

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani (1989) History of Northern Areas of Pakistan, Islamabad : National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, p. 163

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India. Provincial Series: Kashmir and Jammu, ISBN 0-543-91776-2, Adamant, p. 107

- ↑ Reginald Charles (1976) Between the Oxus and the Indus, Francis Schomberg, p. 144

- ↑

- ↑ Henry Osmaston, Philip Denwood (1995) Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., p. 229

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani (1999) History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Motilal Banarsidass Publ, pp. 216–217

- ↑ "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 12 – Imperial Gazetteer of India – Digital South Asia Library". Dsal.uchicago.edu. 18 February 2013. p. 238. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ Prakash Nanda (2007). Rising India: Friends and Foes. Lancer Publishers. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-9796174-1-6.

- ↑ Sir Thomas Douglas Forsyth (1875). Report of a mission to Yarkund in 1873, under command of Sir T. D. Forsyth: with historical and geographical information regarding the possessions of the ameer of Yarkund. Printed at the Foreign department press. p. 56.

- ↑ Bangash, Three Forgotten Accessions 2010, p. 122.

- ↑ Abdullah Sahib

- ↑ Bangash 2010, p. 128: [Ghansara Singh] wrote to the prime minister of Kashmir: 'in case the State accedes to the Indian Union, the Gilgit province will go to Pakistan', but no action was taken on it, and in fact Srinagar never replied to any of his messages.

- ↑ Snedden, Christopher (2013). Kashmir-The Untold Story. HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 9789350298985.

Similarly, Muslims in Western Jammu Province, particularly in Poonch, many of whom had martial capabilities, and Muslims in the Frontier Districts Province strongly wanted J&K to join Pakistan.

- ↑ Schofield 2003, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Bangash 2010

- ↑ Victoria Schofield (2000). Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War. I.B.Tauris. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1-86064-898-4.

- ↑ Yaqoob Khan Bangash (2010) Three Forgotten Accessions: Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38:1, 132, DOI: 10.1080/03086530903538269

- ↑ Yaqoob Khan Bangash (2010) Three Forgotten Accessions: Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38:1, 137, DOI: 10.1080/03086530903538269

- ↑ Bangash, Yaqoob Khan (9 January 2016). "Gilgit-Baltistan—part of Pakistan by choice". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

Nearly 70 years ago, the people of the Gilgit Wazarat revolted and joined Pakistan of their own free will, as did those belonging to the territories of Chilas, Koh Ghizr, Ishkoman, Yasin and Punial; the princely states of Hunza and Nagar also acceded to Pakistan. Hence, the time has come to acknowledge and respect their choice of being full-fledged citizens of Pakistan.

- ↑ Chitralekha Zutshi (2004). Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 309–. ISBN 978-1-85065-700-2.

- ↑ Ershad Mahmud 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ Sokefeld, Martin (November 2005), "From Colonialism to Postcolonial Colonialism: Changing Modes of Domination in the Northern Areas of Pakistan", The Journal of Asian Studies, 64 (4): 939–973, doi:10.1017/S0021911805002287

- ↑ Akhilesh Pillalamarri. "Time for Pakistan to Integrate Gilgit-Baltistan". Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ↑ Alam Zaib. "Somethings about Gilgit". Karachi, Pakistan. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ↑ "Gilgit Climate Data". Pakistan Meteorological Department. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ↑ Bukhari, Shahid Javed (2015). Historical Dictionary of Pakistan. Lahore: Lowman & Littlefield. p. 228.

- ↑ "PM announces construction of Skardu-Gilgit road". Samaa TV. 24 November 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ↑ Ibrahim Shahid (27 March 2004) Gilgit-Srinagar Road: Govt seeks NA admin's opinion. The Daily Times

- ↑ "Havelian to Khunjerab railway track to be upgraded under China-Pakistan Economic Corridor". Sost Today. 4 July 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- Sources

- Bangash, Yaqoob Khan, "Three Forgotten Accessions: Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar", The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38 (1): 117–143, doi:10.1080/03086530903538269, (Subscription required (help))

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, ISBN 1860648983

Further reading

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Gilgit. |

- Window to Gilgit-Baltistan, Regaling tales from past & present of Gilgit-Baltistan

- ApnaGilgit- The real Voice of GB

- Official Website of the Gilgit Baltistan Tourism Department

- Official Website of the Government of Gilgit Baltistan

- Gilgit Nomination, UNESCO, the Memory of the World Register entry document

- Britannica Gilgit