Hyderabad State

| State of Hyderabad | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1724–1948 | |||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

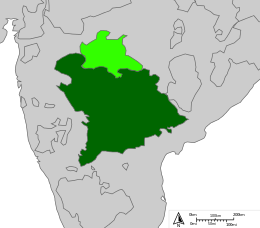

Hyderabad (dark green) and Berar Province not a part of Hyderabad State but also the Nizam's Dominion between 1853 and 1903 (light green). | |||||||||||

| Status |

Independent/Mughal Successor State (1724–1798) Princely state of British India (1798–1947) Unrecognised state (1947–1948) | ||||||||||

| Capital |

Aurangabad (1724–1763) Hyderabad (1763–1948) | ||||||||||

| Common languages |

Urdu (10.3%, official[1]) Persian (historical) Telugu (48.2%) Marathi (26.4%) Kannada (12.3%)[2] | ||||||||||

| Religion |

Islam (13%, state religion[3]) Hinduism (81%) Christianity and others (6%)[4] | ||||||||||

| Government |

Independent/Mughal Successor State (1724–1798)[5][6] Princely State (1798–1950) | ||||||||||

| Nizam | |||||||||||

• 1720–48 | Qamaruddin Khan (first) | ||||||||||

• 1911–56 | Osman Ali Khan (last, as Rajpramukh from 1950) | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

• 1724–1730 | Iwaz Khan (first) | ||||||||||

• 1947-1948 | Mir Laiq Ali (Last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | . | ||||||||||

• Established | 1724 | ||||||||||

| 1946 | |||||||||||

| 18 September 1948 | |||||||||||

| 1 November 1956 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 215,339 km2 (83,143 sq mi) | |||||||||||

| Currency | Hyderabadi rupee | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Princely state |

|---|

| Individual residencies |

| Agencies |

|

| Lists |

Hyderabad State (![]()

History

Early history

Hyderabad State was founded by Mir Qamar-ud-din Khan who was the governor of Deccan under the Mughals from 1713 to 1721. In 1724, he once again resumed rule under the title of Asaf Jah. His other title Nizam ul-Mulk (Order of the Realm), became the title of his position "Nizam of Hyderabad". By the end of his rule, the Nizam had become independent from the Mughals, and had founded the Asaf Jahi dynasty.[13]

Following the decline of the Mughal power, the region of Deccan saw the rise of Maratha Empire. The Nizam himself saw many invasions by the Marathas in the 1720s, which resulted in the Nizam paying a regular tax (Chauth) to the Marathas. The major battles fought between the Marathas and the Nizam include Palkhed, Rakshasbhuvan, and Kharda, in all of which the Nizam lost.[14][15] Following the conquest of Deccan by Bajirao I and the imposition of chauth by him, Nizam remained a tributary of the Marathas for all intent and purposes.[16]

From 1778, a British resident and soldiers were installed in his dominions. In 1795, the Nizam lost some of his own territories to the Marathas. The territorial gains of the Nizam from Mysore as an ally of the British were ceded to the British to meet the cost of maintaining the British soldiers.[13]

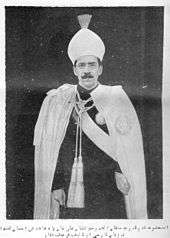

British suzerainty

Hyderabad was a 212,000 km² (82,000 square mile) region in the Deccan, ruled by the head of the Asif Jahi dynasty, who had the title of Nizam and on whom was bestowed the style of "His Exalted Highness" by the British. The last Nizam, Osman Ali Khan, was one of the world's richest men in the 1930s.[17] Hyderabad's Muslim nizams ruled over a predominantly Hindu population.[13]

In 1798, Nizam ʿĀlī Khan (Asaf Jah II) was forced to enter into an agreement that put Hyderabad under British protection. He was the first Indian prince to sign such an agreement. Consequently, Hyderabad was the senior-most (23-gun) salute state during the period of British India. The Crown retained the right to intervene in case of misrule.[13]

Hyderabad under Asaf Jah II was a British ally in the second and third Maratha Wars (1803–05, 1817–19), Anglo-Mysore wars, and remained loyal to the British during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (1857–58).[13]

His son, Asaf Jah III Mir Akbar Ali Khan (known as Sikandar Jah) ruled from 1768 to 1829. During his rule, a British cantonment was built in Hyderabad and the area was named in his honor, Secunderabad.[18] The British Residency at Koti was also built during his reign by the then British Resident James Achilles Kirkpatrick.[19]

Sikander Jah was succeeded by Asaf Jah IV, who ruled from 1829 to 1857, and was succeeded by his son Asaf Jah V.

Asaf Jah V's reign was marked by reforms by his Prime Minister Salar Jung I, included the establishment of a governmental central treasury in 1855. He reformed the Hyderabad revenue and judicial systems, instituted a postal service and constructed the first rail and telegraph networks. In 1861, he was awarded the Star of India. The first higher educational institution of Hyderabad known as Dar-ul-Uloom was estabilished during his reign. [20]

Asaf Jah VI Mir Mahbub Ali Khan became the Nizam at the age of three years. His regents were Salar Jung I and Shams-ul-Umra III. He assumed full rule at the age of 18, and ruled until his death in 1911.[21] During his rule, the Great Musi Flood of 1908 struck the city of Hyderabad, which killed an estimated 50,000 people. The Nizam opened all his palaces for public asylum.[22][23][24] The Nizam's Guaranteed State Railway was also established during his reign to connect Hyderabad State to the rest of British India. It was headquartered at Secunderabad Railway Station. [25][26]

The last Nizam of Hyderabad Mir Osman Ali Khan ruled the state from 1911 until 1948. He was given the title "Faithful Ally of the British Empire". Hyderabad was considered backward, but peaceful, during this time.[13] The Nizam's rule saw growth of Hyderabad economically and culturally. The Osmania University and several schools and colleges were founded throughout the state. Many writers, poets, intellectuals and other eminent people (including Fani Badayuni, Dagh Dehlvi, Josh Malihabadi, Ali Haider Tabatabai, Shibli Nomani, Nawab Mohsin-ul-Mulk, Mirza Ismail) migrated from all parts of India to Hyderabad, during the reign of Asaf Jah VII, and his father and predecessor Asaf Jah VI.

The Nizam also established Hyderabad State Bank. Hyderabad was the only state in British India which had its own currency, the Hyderabadi rupee. [27] The Begumpet Airport was established in the 1930's with formation of Hyderabad Aero Club by the Nizam. Initially it was used as a domestic and international airport for the Nizam's Deccan Airways, the earliest airline in British India. The terminal building was created in 1937.[28]

In order to prevent another great flood, the Nizam also constructed two lakes, namely the Osman Sagar and Himayath Sagar. The Osmania General Hospital, Jubilee Hall, Moazzam Jahi Market, State Library (then known as Asifia Kutubkhana) and Public Gardens (then known as Bagh e Aam) were constructed during this period. [29][30]

After Indian Independence (1947–48)

In 1947 India gained independence and Pakistan came into existence; the British left the local rulers of the princely states the choice of whether to join one or the other, or to remain independent. On 11 June 1947, the Nizam issued a declaration to the effect that he had decided not to participate in the Constituent Assembly of either Pakistan or India. India insisted that the great majority of residents wanted to join India.[31]

The Nizam was in a weak position as his army numbered only 24,000 men, of whom only some 6,000 were fully trained and equipped.[32]

On 21 August 1948, the Secretary-General of the Hyderabad Department of External Affairs requested the President of the United Nations's Security Council, under Article 35(2) of the United Nations Charter, to consider the "grave dispute, which, unless settled in accordance with international law and justice, is likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and security".[33]

On 4 September the Prime Minister of Hyderabad Mir Laiq Ali announced to the Hyderabad Assembly that a delegation was about to leave for Lake Success, headed by Moin Nawaz Jung.[34] The Nizam also appealed, without success, to the British Labour Government and to the King for assistance, to fulfil their obligations and promises to Hyderabad by "immediate intervention". Hyderabad only had the support of Winston Churchill and the British Conservatives.[35]

At 4 a.m. on 13 September 1948, India's Hyderabad Campaign, code-named "Operation Polo" by the Indian Army, began. Indian troops invaded Hyderabad from all points of the compass. On 13 September 1948, the Secretary-General of the Hyderabad Department of External Affairs in a cablegram informed the United Nations Security Council that Hyderabad was being invaded by Indian forces and that hostilities had broken out. The Security Council took notice of it on 16 September in Paris. The representative of Hyderabad called for immediate action by the Security Council under chapter VII of the United Nations Charter. The Hyderabad representative responded to India's excuse for the intervention by pointing out that the Stand-still Agreement between the two countries had expressly provided that nothing in it should give India the right to send in troops to assist in the maintenance of internal order.[36]

At 5 p.m. on 17 September the Nizam's army surrendered. India then incorporated the state of Hyderabad into the Union of India and ended the rule of the Nizams.[37]

1948–56

After the incorporation of Hyderabad State into India, M. K. Vellodi was appointed as Chief Minister of the state on 26 January 1950. He was a Senior Civil servant in the Government of India. He administered the state with the help of bureaucrats from Madras state and Bombay state.[38]

In the 1952 Legislative Assembly election, Dr. Burgula Ramakrishna Rao was elected Chief minister of Hyderabad State. During this time there were violent agitations by some Telanganites to send back bureaucrats from Madras state, and to strictly implement 'Mulki-rules'(Local jobs for locals only), which was part of Hyderabad state law since 1919.[39]

Dissolution

In 1956 during the Reorganisation of the Indian States based along linguistic lines, the state of Hyderabad was split up among Andhra Pradesh and Bombay state (later divided into states of Maharashtra and Gujarat in 1960 with the original portions of Hyderabad becoming part of the state of Maharashtra) and Karnataka.[40]

Government and politics

Government

Wilfred Cantwell Smith states that Hyderabad was an area where the political and social structure from medieval Muslim rule had been preserved more or less intact into the modern times.[41] At the head of the social order was the Nizam, who owned 5 million acres (10% of the land area) of the state, earning him Rs. 25 million a year. Another Rs. 5 million was granted to him from the state treasury. He was reputed to be the wealthiest man in the world.[42] He was supported by an aristocracy of 1,100 feudal lords who owned a further 30% of the state's land, with some 4 million tenant farmers. The state also owned 50% or more of the capital in all the major enterprises, allowing the Nizam to earn further profits and control their affairs.[43]

Next in the social structure were the administrative and official class, comprising about 1,500 officials. A number of them were recruited from outside the state. The lower level government employees were also predominantly Muslim. Effectively, the Muslims of the Hyderabad represented an 'upper caste' of the social structure. They dominated the state's extensive Hindu population, who resented their dominance.[44] However many Hindus served in high government posts such as Prime Minister of Hyderabad (Maharaja Chandu Lal, Maharaja Sir Kishen Pershad) and Kotwal of Hyderabad (Raja Bahadur Venkatarama Reddy).

All power was vested in the Nizam. He ruled with the help of an Executive Council or Cabinet, established in 1893, whose members he was free to appoint and dismiss. There was also an Assembly, whose role was mostly advisory. More than half its members were appointed by the Nizam and the rest elected from a carefully limited franchise. There were representatives of Hindus, Parsis, Christians and Depressed Classes in the Assembly. Their influence was however limited due to their small numbers.[45][46]

The state government also had a large number of outsiders (called non-mulkis) — 46,800 of them in 1933, including all the members of the Nizam's Executive Council. Hindus and Muslims united in protesting against the practice which robbed the locals of government employment. The movement however fizzled out after the Hindu members raised the issue of 'responsible government', which was of no interest to the Muslim members and led to their resignation.[47]

Political movements

Up to 1920, there was no political organisation of any kind in Hyderabad. In that year, following British pressure, the Nizam issued a firman appointing a special officer to investigate constitutional reforms. It was welcomed enthusiastically by a section of the populace, who formed the Hyderabad State Reforms Association. However, the Nizam and the Special Officer ignored all their demands for consultation. Meanwhile, the Nizam banned the Khilafat movement in the State as well as all political meetings and the entry of "political outsiders". Nevertheless, some political activity did take place and witnessed co-operation between Hindus and Muslims. The abolition of the Sultanate in Turkey and Gandhi's suspension of the Non-co-operation movement in British India ended this period of co-operation.[46]

An organisation called Andhra Jana Sangham (later renamed Andhra Mahasabha) was formed in November 1921, and focused on educating the masses of Telangana in political awareness. With leading members such as Madapati Hanumantha Rao, Burgula Ramakrishna Rao and M. Narsing Rao, its activities included urging merchants to resist offering freebies to government officials and encouraging labourers to resist the system of begar (free labour requested at the behest of state). Alarmed by its activities, the Nizam passed a powerful gagging order in 1929, requiring all public meetings to obtain prior permission. But the organisation persisted by mobilising on social issues such as the protection of ryots, women's rights, abolition of the devadasi system and purdah, uplifting of Dalits etc. It turned to politics again in 1937, passing a resolution calling for responsible government. Soon afterwards, it split along the moderate–extremist lines. The Andhra Mahasabha's move towards politics also inspired similar movements in Marathwada and Karnataka in 1937, giving rise to the Maharashtra Parishad and Karnataka Parishad respectively.[46]

The Arya Samaj, a pan-Indian Hindu reformist movement that engaged in a forceful religious conversion programme, established itself in the state in the 1890s, first in the Bhir and Bidar districts. By 1923, it opened a branch in the Hyderabad city. Its mass conversion programme in 1924 gave rise to tensions, and the first clashes occurred between Hindus and Muslims.[46] The Arya Samaj was allied to the Hindu Mahasabha, another pan-Indian Hindu communal organisation, which also had branches in the state. The anti-Muslim sentiments represented by the two organisations was particularly strong in Marathwada.[48]

In 1927, the first Muslim political organisation, Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (Council for the Unity of Muslims, Ittehad for short) was formed. Its political activity was meagre during the initial decade other than stating the objectives of uniting the Muslims and expressing loyalty to the ruler. However, it functioned as a 'watchdog' of Muslim interests and defended the privileged position of Muslims in the government and administration.[46]

1938 Satyagraha

1937 was a watershed year in the Indian independence movement. The Government of India Act, 1935 introduced major constitutional reforms, with a loose federal structure for India and provincial autonomy. In the provincial elections of February 1937, the Indian National Congress emerged with clear majority in most provinces of British India and formed provincial governments.

On the other hand, there was no move towards constitutional reforms in the Hyderabad state despite the initial announcement in 1920. The Andhra Mahasabha passed a resolution in favour of responsible government and the parallel organisations of Maharastrha Parishad and Karnataka Parishad were formed in their respective regions. The Nizam appointed a fresh Constitutional Reforms Committee in September 1937. However, the gagging orders of the 1920s remained curtailing the freedom of press and restrictions on public speeches and meetings. In response, a 'Hyderabad People's Convention' was created, with a working committee of 23 leading Hindus and 5 Muslims. The convention ratified a report, which was submitted to the Constitutional Reforms Committee in January 1938. However, four of the five Muslim members of the working committee refused to sign the report, reducing its potential impact.[49]

In February 1938, the Indian National Congress passed the Haripura resolution declaring that the princely states are "an integral part of India," and that it stood for "the same political, social and economic freedom in the States as in the rest of India". Encouraged by this, the standing committee of the People's Convention proposed to form a Hyderabad State Congress and an enthusiastic drive to enroll members was begun. By July 1938, the committee claimed to have enrolled 1200 primary members and declared that elections would soon be held for the office-bearers. It called upon both Hindus and Muslims of the state to "shed mutual distrust" and join the "cause of responsible government under the aegis of the Ashaf Jahi dynasty." The Nizam responded by passing a new Public Safety Act on 6 September 1938, three days before the scheduled elections, and issued an order that the Hyderabad State Congress would be deemed unlawful.[49]

Negotiations with the Nizam's government to lift the ban ended in failure. The Hyderabad issue was widely discussed in the newspapers in British India. P. M. Bapat, a leader of the Indian National Congress from Pune, declared that he would launch a satyagraha (civil disobedience movement) in Hyderabad starting 1 November. The Arya Samaj and Hindu Mahasabha also planned to launch satyagrahas on the matter of Hindu civil rights. The Hindu communal pot had been boiling since early 1938 when an Arya Samaj member in Osmanabad district was said to have been murdered for refusing to convert to Islam. In April, there was a communal riot in Hyderabad that pitted Muslims against Hindus that raised the allegation of 'oppression of Hindus' in the press in British India. The Arya Samaj leaders hoped to capitalise on these tensions. Perhaps in a bid not to be outdone, the activists of the Hyderabad State Congress formed a 'Committee of Action' and initiated a satyagraha on 24 October 1938. The members of the organisation openly declared they belong to the Hyderabad State Congress and courted arrest. The Arya Samaj-Hindu Mahasabha combine also launched their own satyagraha on the same day.[49]

The Indian National Congress refused to back the satyagraha of the State Congress. The Haripura resolution had in fact been a compromise between the moderates and the radicals. Gandhi had been wary of direct involvement in the states lest the agitations degenerate into violence. The Congress high command was also keen on a firmer collaboration between Hindus and Muslims, which the State Congress lacked. Padmaja Naidu wrote a lengthy report to Gandhi where she castigated the State Congress for lacking unity and cohesion and for being 'communal in [her] sense of the word'. On 24 December, the State Congress suspended the agitation after 300 activists had courted arrest. These activists remained in jail till 1946.[49][50]

The Arya Samaj-Hindu Mahasabha combine continued their agitation and intensified it in March 1949. However, the response from the state's Hindus was lacklustre. Of the 8,000 activists that courted arrest by June, about 20% were estimated to be state's residents; the rest were mobilised from British India. The surrounding British Indian provinces of Bombay and Central Provinces and, to limited extent, Madras, all governed by Indian National Congress, facilitated the mobilisation, with town such as Ahmednagar, Sholapur, Vijayawada, Pusad and Manmad used as staging posts. Increasingly strident anti-Hyderabad propaganda continued in British India. By July–August, the tensions had eased. The Hindu Mahasabha dispatched the Shankaracharya of Jyotirmath on a peace mission, who testified that there was no religious persecution of Hindus in the state. The Nizam government set up a Religious Affairs Committee and announced constitutional reforms by 20 July. Subsequently, the Hindu Mahasabha suspended its campaign on 30 July and the Arya Samaj on 8 August. All the imprisoned activists of the two organisations were released.[49]

Communal violence

Prior to the operation

In the 1936–37 Indian elections, the Muslim League under Muhammad Ali Jinnah had sought to harness Muslim aspirations, and had won the adherence of MIM leader Nawab Bahadur Yar Jung, who campaigned for an Islamic State centred on the Nizam as the Sultan dismissing all claims for democracy. The Arya Samaj, a Hindu revivalist movement, had been demanding greater access to power for the Hindu majority since the late 1930s, and was curbed by the Nizam in 1938. The Hyderabad State Congress joined forces with the Arya Samaj as well as the Hindu Mahasabha in the State.[51]

Noorani regards the MIM under Nawab Bahadur Yar Jung as explicitly committed to safeguarding the rights of religious and linguistic minorities. However, this changed with the ascent of Qasim Razvi after the Nawab's death in 1944.[52]

Even as India and Hyderabad negotiated, most of the sub-continent had been thrown into chaos as a result of communal Hindu-Muslim riots pending the imminent partition of India. Fearing a Hindu civil uprising in his own kingdom, the Nizam allowed Razvi to set up a voluntary militia of Muslims called the 'Razakars'. The Razakars – who numbered up to 200,000 at the height of the conflict – swore to uphold Islamic domination in Hyderabad and the Deccan plateau[53]:8 in the face of growing public opinion amongst the majority Hindu population favouring the accession of Hyderabad into the Indian Union.

According to an account by Mohammed Hyder, a civil servant in Osmanabad district, a variety of armed militant groups, including Razakars and Deendars and ethnic militias of Pathans and Arabs claimed to be defending the Islamic faith and made claims on the land. "From the beginning of 1948 the Razakars had extended their activities from Hyderabad city into the towns and rural areas, murdering Hindus, abducting women, pillaging houses and fields, and looting non-Muslim property in a widespread reign of terror."[54][55] "Some women became victims of rape and kidnapping by Razakars. Thousands went to jail and braved the cruelties perpetuated by the oppressive administration. Due to the activities of the Razakars, thousands of Hindus had to flee from the state and take shelter in various camps".[56] Precise numbers are not known, but 40,000 refugees have been received by the Central Provinces.[53]:8 This led to terrorizing of the Hindu community, some of whom went across the border into independent India and organized raids into Nizam's territory, which further escalated the violence. Many of these raiders were controlled by the Congress leadership in India and had links with extremist religious elements in the Hindutva fold.[57] In all, more than 150 villages (of which 70 were in Indian territory outside Hyderabad State) were pushed into violence.

Hyder mediated some efforts to minimize the influence of the Razakars. Razvi, while generally receptive, vetoed the option of disarming them, saying that with the Hyderabad state army ineffective, the Razakars were the only means of self-defence available. By the end of August 1948, a full blown invasion by India was imminent.[58]

Nehru was reluctant to invade, fearing a military response by Pakistan. India was unaware that Pakistan had no plans to use arms in Hyderabad, unlike Kashmir where it had admitted its troops were present.[53] Time magazine pointed out that if India invaded Hyderabad, the Razakars would massacre Hindus, which would lead to retaliatory massacres of Muslims across India.[59]

During and after the operation

There were reports of looting, mass murder and rape of Muslims in reprisals by Hyderabadi Hindus.[60][55] Jawaharlal Nehru appointed a mixed-faith committee led by Pandit Sunder Lal to investigate the situation. The findings of the report (Pandit Sunderlal Committee Report) were not made public until 2013 when it was accessed from the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library in New Delhi.[60][61]

The Committee concluded that while Muslim villagers were disarmed by the Indian Army, Hindus were often left with their weapons.[60] The violence was carried out by Hindu residents, with the army sometimes indifferent, and sometimes participating in the atrocities.[53]:11 The Committee stated that large-scale violence against Muslims occurred in Marathwada and Telangana areas. It also concluded: "At a number of places members of the armed forces brought out Muslim adult males from villages and towns and massacred them in cold blood."[60] The Committee generally credited the military officers with good conduct but stated that soldiers acted out of bigotry.[53]:11 The official "very conservative estimate" was that 27,000 to 40,000 died "during and after the police action."[60] Other scholars have put the figure at 200,000, or even higher.[62] Among Muslims some estimates were even higher and Smith says that the military government's private low estimates [of Muslim casualties] were at least ten times the number of murders with which the Razakers were officially accused.[63] In William Dalrymple's words the scale of the killing was horrific. Although Nehru played down this violence, he was privately alarmed at the scale of anti-Muslim violence.[64]

Patel reacted angrily to the report and disowned its conclusions. He stated that the terms of reference were flawed because they only covered the part during and after the operation. He also cast aspersions on the motives and standing of the committee. These objections are regarded by Noorani as disingenuous because the commission was an official one, and it was critical of the Razakars as well.[62][65]

According to Mohammed Hyder, the tragic consequences of the Indian operation were largely preventable. He faulted the Indian army with neither restoring local administration, nor setting up their own military administration. As a result, the anarchy led to several thousand "thugs", from the camps set up across the border, filling the vacuum. He stated "Thousands of families were broken up, children separated from their parents and wives, from their husbands. Women and girls were hunted down and raped."[66] The Committee Report mentions mass rape of Muslim women by Indian troops.[64]

According to the communist leader Puccalapalli Sundarayya, Hindus in villages rescued thousands of Muslim families from the Union Army's campaign of rape and murder.[67]

Industries

Various major industries emerged in various parts of the State of Hyderabad before its incorporation into the Union of India, especially during the first half of the twentieth century. Hyderabad city had a separate powerplant for electricity. However, the Nizams focused industrial development on the region of Sanathnagar, housing a number of industries there with transportation facilities by both road and rail.[68]

| Company | Year |

|---|---|

| Nizam's Guaranteed State Railway | 1879 |

| Karkhana Zinda Tilismat | 1920 |

| Singareni Collieries | 1921 |

| Hyderabad Deccan Cigarette Factory | 1922 |

| Vazir Sultan Tobacco Company, Charminar cigarette factory | 1930 |

| Azam Jahi Mills Warangal | 1934 |

| Nizam Sugar Factory | 1937 |

| Allwyn Metal Works | 1942 |

| Praga Tools | 1943 |

| Deccan Airways Limited | 1945 |

| Hyderabad Asbestos | 1946 |

| Sirsilk | 1946 |

See also

- Hyderabad State (1948–56)

- Hyderabadi Muslim

- Hyderabadi Urdu, the local dialect of Urdu

- Hyderabad, India, the Indian city that served as capital of Hyderabad State

- Hyderabad, Sindh, another city with the same name in Sindh Pakistan

- Nizam of Hyderabad for a list of Nizams and other information

- Telangana and Marathwada, regions formerly in Hyderabad State

- Hyderabad Police Action, the military invasion that resulted in the annexation of Hyderabad state into India

- List of Indian princely states

- Dakhini

- Handley Page Hyderabad

- Hyderabad State Forces, the armed forces of Hyderabad State

Notes

References

- ↑ Beverley, Hyderabad, British India, and the World 2015, p. 110.

- ↑ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 20.

- ↑ O'Dwyer, Michael (1988), India as I Knew it: 1885–1925, Mittal Publications, pp. 137–, GGKEY:DB7YTGYWP7W

- ↑ Smith 1950, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (2004), Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy (Second ed.), Routledge, p. 42, ISBN 978-0-415-30787-1

- ↑ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, Chapter 7: "'Operation Polo', the code name for the armed invasion of Hyderabad"

- ↑ Ali, Cherágh (1886). Hyderabad (Deccan) Under Sir Salar Jung. Printed at the Education Society's Press.

- ↑ Report on the Medical Topography and Statistics of the Northern, Hyderabad and Nagpore Divisions, the Tenasserim Provinces, and the Eastern Settlements. printed at Vepery Mission Press. 1844.

- ↑ Pike, Francis (2011-02-28). Empires at War: A Short History of Modern Asia Since World War II. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857730299.

- ↑ Sherman, Taylor C. (2007), "The integration of the princely state of Hyderabad and the making of the postcolonial state in India, 1948–56", The Indian Economic and Social History Review, 44 (4): 489–516, doi:10.1177/001946460704400404, (Subscription required (help))

- ↑ Chandra, Mukherjee & Mukherjee 2008, p. 96.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Hyderabad". Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ↑ "Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: P-Z". google.com.pk.

- ↑ "The State at War in South Asia". google.com.pk.

- ↑ Nath Sen, Sailendra. "Anglo-Maratha Relations, 1785–96, Volume 2". google.co.in.

- ↑ Time dated 22 February 1937, cover story

- ↑ http://www.uq.net.au/~zzhsoszy/ips/h/hyderabad.html

- ↑ Dalrymple, William (2004). White Mughals: love and betrayal in eighteenth-century India. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-200412-8.

- ↑ https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/hyderabad/osmania-university-first-to-teach-in-blend-of-urdu-amp-english/articleshow/57366802.cms

- ↑ "Nizam of Hyderabad Dead", New York Times, 30 August 1911

- ↑ https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH19081003.2.42&srpos=24&e=-------en--20--21--txt-txIN-hyderabad------

- ↑ "Hyderabad to observe 104th anniversary of Musi flood | The Siasat Daily". archive.siasat.com. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- ↑ ""Hyderabad to observe 104th anniversary of Musi flood"". The Siasat Daily.

- ↑ "Inspecting Officers (Railways) – Pringle, (Sir) John Wallace". SteamIndex. Retrieved 2011-07-10.

- ↑ Nayeem, M. A.; The Splendour of Hyderabad; Hyderabad ²2002 [Orig.: Bombay ¹1987]; ISBN 81-85492-20-4; S. 221

- ↑ Pagdi, Raghavendra Rao (1987) Short History of Banking in Hyderabad District, 1879-1950. In M. Radhakrishna Sarma, K.D. Abhyankar, and V.G. Bilolikar, eds. History of Hyderabad District, 1879-1950AD (Yugabda 4981-5052). (Hyderabad : Bharatiya Itihasa Sankalana Samiti), Vol. 2, pp.85-87.

- ↑ "Begumpeet Airport History". Archived from the original on 21 December 2005.

- ↑ http://spaceandculture.in/index.php/spaceandculture/article/view/121/78

- ↑ Pandey, Dr. Vinita. "Changing Facets of Hyderabadi Tehzeeb: Are We Missing Anything?".

- ↑ Purushotham, Sunil (2015). "Internal Violence: The "Police Action" in Hyderabad". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 57 (2): 435–466. doi:10.1017/s0010417515000092.

- ↑ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 229.

- ↑ "The Hyderabad Question" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ↑ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 230.

- ↑ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 231.

- ↑ United Nations Document S/986

- ↑ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 232.

- ↑ APonline - History and Culture - History-Post-Independence Era Archived 20 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Mulki agitation in Hyderabad state". Hinduonnet.com. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ↑ "SRC submits report". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 1 October 2005. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Smith 1950, p. 28.

- ↑ Guha 2008, p. 51.

- ↑ Smith 1950, p. 29.

- ↑ Smith 1950, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Smith 1950, pp. 30–31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, Chapter 2.

- ↑ Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Smith 1950, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Benichou, Autocracy to Integration 2000, Chapter 3.

- ↑ Smith 1950, pp. 32, 42.

- ↑ Noorani 2014, pp. 51–61.

- ↑ Muralidharan 2014, pp. 128–129.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sherman, Taylor C. (2007). "The integration of the princely state of Hyderabad and the making of the postcolonial state in India, 1948 – 56" (PDF). Indian economic & social history review. 44 (4): 489–516. doi:10.1177/001946460704400404.

- ↑ By Frank Moraes, Jawaharlal Nehru, Mumbai: Jaico.2007, p.394

- 1 2 Kate, P. V., Marathwada Under the Nizams, 1724–1948, Delhi: Mittal Publications, 1987, p.84

- ↑ Kate, P. V., Marathwada Under the Nizams, 1724-1948, Delhi: Mittal Publications, 1987, p.84

- ↑ Muralidharan 2014, p. 132.

- ↑ Muralidharan 2014, p. 134.

- ↑ "HYDERABAD: The Holdout". Time. 30 August 1948. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thomson, Mike (24 September 2013). "Hyderabad 1948: India's hidden massacre". BBC. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ↑ http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/hyderabad/Lessons-to-learn-from-Hyderabads-past/articleshow/27390337.cms

- 1 2 Noorani, A.G. (3–16 March 2001), "Of a massacre untold", Frontline, 18 (05), retrieved 8 September 2014,

The lowest estimates, even those offered privately by apologists of the military government, came to at least ten times the number of murders with which previously the Razakars were officially accused...

- ↑ Benichou, From Autocracy to Integration 2000, p. 238.

- 1 2 Dalrymple, William. The Age of Kali: Indian Travels and Encounters. p. 210.

- ↑ Muralidharan 2014, p. 136.

- ↑ Muralidharan 2014, p. 135.

- ↑ Sundarayya, Puccalapalli (1972). Telangana People's Struggle and Its Lessons. Foundation Books. p. 14.

- 1 2 "Kaleidoscopic view of Deccan". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 25 August 2009.

Bibliography

- Benichou, Lucien D. (2000), From Autocracy to Integration: Political Developments in Hyderabad State, 1938–1948, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-81-250-1847-6

- Beverley, Eric Lewis (2015), Hyderabad, British India, and the World, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-09119-1

- Chandra, Bipan; Mukherjee, Aditya; Mukherjee, Mridula (2008) [first published 1999], India Since Independence, Penguin Books India, ISBN 978-0-14-310409-4

- Faruqi, Munis D. (2013), "At Empire's End: The Nizam, Hyderabad and Eighteenth-century India", in Richard M. Eaton; Munis D. Faruqui; David Gilmartin; Sunil Kumar, Expanding Frontiers in South Asian and World History: Essays in Honour of John F. Richards, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–38, ISBN 978-1-107-03428-0

- Guha, Ramachandra (2008), India after Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy, Pab Macmillian, ISBN 0-330-39611-0

- Smith, Wilfred Cantwell (January 1950), "Hyderabad: Muslim Tragedy", Middle East Journal, 4 (1): 27–51, JSTOR 4322137

- Ram Narayan Kumar (1 April 1997), The Sikh unrest and the Indian state: politics, personalities, and historical retrospective, The University of Michigan, p. 99, ISBN 978-81-202-0453-9

- Jayanta Kumar Ray (2007), Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World, Pearson Education India, p. 206, ISBN 978-81-317-0834-7

Further reading

- Faruqi, Munis D. (2013), "At Empire's End: The Nizam, Hyderabad and Eighteenth-century India", in Richard M. Eaton; Munis D. Faruqui; David Gilmartin; Sunil Kumar, Expanding Frontiers in South Asian and World History: Essays in Honour of John F. Richards, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–38, ISBN 978-1-107-03428-0

- Hyderabad State. Imperial Gazetteer of India Provincial Series. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers. 1989.

- Iyengar, Kesava (2007). Economic Investigations in the Hyderabad State 1939–1930. 1. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-6435-2.

- Leonard, Karen (1971). "The Hyderabad Political System and its Participants". Journal of Asian Studies. 30 (3): 569–582. doi:10.1017/s0021911800154841. JSTOR 2052461.

- Pernau, Margrit (2000). The Passing of Patrimonialism: Politics and Political Culture in Hyderabad, 1911–1948. Delhi: Manohar. ISBN 81-7304-362-0.

- Purushotham, Sunil (2015). "Internal Violence: The "Police Action" in Hyderabad". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 57 (2): 435–466. doi:10.1017/S0010417515000092.

- Sherman, Taylor C. "Migration, citizenship and belonging in Hyderabad (Deccan), 1946–1956." Modern Asian Studies 45#1 (2011): 81–107.

- Sherman, Taylor C. "The integration of the princely state of Hyderabad and the making of the postcolonial state in India, 1948–56." Indian Economic & Social History Review 44#4 (2007): 489–516.

- Various (2007). Hyderabad State List of Leading Officials, Nobles and Personages. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-3137-8.

- Zubrzycki, John (2006). The Last Nizam: An Indian Prince in the Australian Outback. Australia: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-42321-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hyderabad State. |

- Hyderabad City Information Portal

- Hyderabad: A Qur'anic Paradise in Architectural Metaphors

- From the Sundarlal Report – Muslim Genocide in 1948

- Manolya's legal fight

- About Razakars and Islamic ambitions

- Hyderabad

- Genealogy of the Nizams of Hyderabad

- Renaming villages by the Nizam