2001–02 India–Pakistan standoff

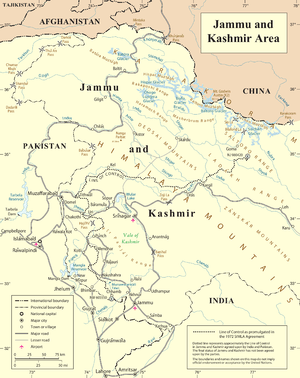

The 2001–2002 India–Pakistan standoff was a military standoff between India and Pakistan that resulted in the massing of troops on either side of the border and along the Line of Control (LoC) in the region of Kashmir. This was the second major military standoff between India and Pakistan following the successful detonation of nuclear devices by both countries in 1998 and the most recent standoff between the nuclear rivals. The other had been the Kargil War in 1999.

The military buildup was initiated by India responding to a terrorist attack on the Indian Parliament on 13 December 2001 (during which twelve people, including the five men who attacked the building, were killed) and the legislative Assembly on 1 October 2001.[4] India claimed that the attacks were carried out by two Pakistan-based terror groups fighting Indian administered Kashmir, the Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad, both of whom India has said are backed by Pakistan's ISI –[5] a charge that Pakistan denied.[6][7][8]

In the Western media, coverage of the standoff focused on the possibility of a nuclear war between the two countries and the implications of the potential conflict on the American-led "Global War on Terrorism" in nearby Afghanistan. Tensions de-escalated following international diplomatic mediation which resulted in the October 2002 withdrawal of Indian[9] and Pakistani troops[10] from the international border.

Prelude

On the morning of 13 December 2001, a cell of five armed men attacked the Indian Parliament by breaching the security cordon at Gate 12. The five men killed seven people before being shot dead by Indian Security Forces.

World leaders and leaders in nearby countries condemned the attack on the Parliament, including Pakistan. On 14 December, the ruling Indian National Democratic Alliance blamed Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) for the attack. Home Minister L.K. Advani claimed, "we have received some clues about yesterday's incident, which shows that a neighboring country, and some terrorist organisations active there are behind it,"[11] in an indirect reference to Pakistan and Pakistan-based militant groups. The same day, in a demarche to Pakistan's High Commissioner to India, Ashraf Jehangir Qazi, India demanded that Pakistan stop the activities of LeT and JeM, that Pakistan apprehend the organisation's leaders and that Pakistan curb the financial assets and the group's access to these assets.[12] In response to the Indian government's statements, Pakistan ordered its military on standing high alert the same day.

The Pakistan military's information sources, the ISPR's spokesman Major-General Rashid Qureshi, claimed that the Parliament attack was a "drama staged by Indian intelligence agencies to defame the freedom struggle in 'occupied Kashmir'" and further warned that India would pay "heavily if they engage in any misadventure".[13]

On 20 December, amid calls from the United States, Russia, and the United Nations to exercise restraint, India mobilised and deployed its troops to Kashmir and the Indian part of the Punjab in what was India's largest military mobilization since the 1971 conflict.[14] The Indian codename for the mobilization was Operation Parakram (Sanskrit: Valor).[15]

January Offensive

Planning

The troop deployment to India's western border was expected to take three to four weeks, accordingly the military action involving a limited offensive against the terrorists' training camps in Pak administered Kashmir was planned by the Indian Cabinet Committee on Security for the second week of January 2002. It would start with air strike by IAF's Tiger Squadron to attack zones with large concentration of camps. Special forces of the Indian army would then launch a limited ground offensive to further neutralise the terrorist camps and help to occupy the dominant positions on the LoC. January 14, 2002 was decided as the tentative D-day.[16]

According to the Indian strategy a limited strike in the Pakistan administered Kashmir was preferred as it would convey the Indian resolve to Pakistan and yet keep the international retribution levels that are manageable. Indian actions would then be comparable to the, ongoing US offensive in Afghanistan against Osama bin Laden's Al-Qaida terrorists.[16]

The CCS had weighed in the possibility of Pakistan launching an all-out offensive as a response to the Indian strikes. The intelligence assessment suggested that the Pakistani Army was not well prepared. This further minimized the chances of Pakistan launching a full-scale war. The Indian plans were strengthened by a strong economy with low inflation, high petroleum and forex reserves. Finance minister Yashwant Sinha announced that the Indian economy was prepared for a war, in spite of being the final option. The limited strike served as a tactical option. The troop build-up signalled "India's seriousness" to the international community and the USA. If Pakistan's strategy did not change then India would have no other option.[16]

Military Confrontations

In late December, both countries moved ballistic missiles closer to each other's border, and mortar and artillery fire was reported in Kashmir.[17] By January 2002, India had mobilized around 500,000 troops and three armored divisions on the Pakistan's border concentrated along the Line of Control in Kashmir. Pakistan responded similarly, deploying around 300,000 troops to that region.[1] The tensions were partially diffused after Musharraf's speech on 12 January promising action on terror emanating from Pakistan.[16]

Diplomacy

India initiated its diplomatic offensive by recalling Indian high commissioner and the civilian flights from Pakistan were banned.[16]

Pakistan picked up the war signals and began mobilisation of its military and initiated diplomatic talks with the US President George W. Bush. American Secretary of State Colin Powell engaged with India and Pakistan to reduce tensions. In the first week of January, British Prime Minister Tony Blair visited India with a message that he was pressurising Pakistani President Musharraf. USA declared LeT and JeM as foreign terrorist groups.[16]

Musharraf's Speech

On January 8 2002, Indian Home Minister L. K. Advani visited the US, where he was informed about the contents of the upcoming landmark speech by Musharraf.[16] On 12 January 2002, President Pervez Musharraf gave a speech intended to reduce tensions with India. He for the first time condemned the attack on Parliament as a terrorist attack and compared it with the September 11 attacks.[18] He declared in his speech that terrorism was unjustified in the name of Kashmir and Pakistan would combat extremism on its own soil. Pakistan would resolve Kashmir with dialogue and no organisation will be allowed to carry out terrorism under the pretext of Kashmir.[19] As demanded by India, he also announced plans for the regulation of madarsas and banning the known terrorist groups that were operating out of Pakistan.[16] He announced a formal ban on five jihadi organizations, that included Jaish-e-Muhammad and Lashkar-e-Taiba engaged in militancy in Kashmir.[18]

Indian decision

The Indian Prime Minister though skeptic of the seriousness of Musharraf's pledges, decided not to carry out the military attack planned for 14th January.[18]

Apart from Musharraf's speech there was another factor that postponed the CCS plans of an immediate war. Pakistan had moved out most of terrorist training camps from Pakistan administered Kashmir in January this meant that to achieve militarily significant results the Indian forces would have to cross the international borders. This would have been risky as it would show India as an aggressor and could have invited global intervention on Kashmir. It was decided by CCS to give Musharraf another chance but the armed forces were kept fully mobilised for war.[16]

Kaluchak Massacre

Tensions escalated significantly in May. On 14 May, three suicidal terrorists attacked an Army camp at Kaluchak near Jammu and killed 34 people and injured fifty more before getting killed, most of the victims were the wives and children of Indian soldiers serving in Kashmir. The terrorist incident again revived the chance of a full blown war.[18]

On 15 May, PM Vajpayee was quoted in the Indian Parliament saying "Hamein pratikar karna hoga ( We will have to counter it)."[16] American Foreign Minister Armitage quoted the incident as a trigger for further deterioration of the situation.[18]

Indian Cabinet had little belief that diplomatic pressure could stop Pakistan's support for the militants in Kashmir. India accused Pakistan that it was failing to keep its promise on ending the cross-border terrorism.[16] Musharraf's follow-up to his speech on January 12th was observed by India as weak and disingenuous. Pakistan did not extradite the terrorist leaders demanded by India, and Lashkar was allowed to continue its operations in Pakistan as a charity with a new name. During the spring, jihadi militants started crossing the Line of Control again.[18]

June Offensive

Planning

On May 18, Vajpayee reviewed the preparedness with the Defence Minister Fernandez, Director-General Military Operations and Military Intelligence Chief. The CCS met and favoured taking military action against terrorists in Pakistan. A limited military action similar to the one planned in January was not considered viable as Pakistan had strengthened its forces on the LoC. Any action limited to Pakistan administered Kashmir would only have limited military gains. Indian military favoured an offensive along the Indo-Pak border that will stretch the Pakistani troops and provide India an access to Pakistan administered Kashmir.[16]

The Indian armed forces accordingly prepared the plan target the war waging capabilities of Pakistan and destroy the terrorist camps. The battle canvas planned for June was larger than the one planned in January. The Indian Air Force along with 1 Strike Corps of Indian would initiate attack in Shakargarh bulge to engage Pakistan's Army Reserve North (ARN) that was spread from Muzaffarabad to Lahore. This would engage Pakistan's key strike corp while Indian strike formations from Eastern command would carry out the offensive at the Line of Control and capture the strategic positions used by the terrorists for infiltrations. The period considered was between 23 May and 10 June.[16]

Military Confrontations

During the end of May 2002, the Indian and Pakistani armed forces continued to be fully mobilized. The tenor of statements published in the Indian press and intelligence information collected, pointed to an imminent invasion by India.[18] An SOS was sent to Israel by the Indian Defence Ministry for defence supplies during the month of June confirmed the intelligence.[16]

On 18 May, India expelled the Pakistani High Commissioner. That same day, thousands of villagers had to flee Pakistani artillery fire in Jammu.[20] On 21 May, clashes killed six Pakistani soldiers and 1 Indian soldier, as well as civilians from both sides.[21] On 22 May, Indian Prime Minister Vajpayee announced to his troops to prepare for a "decisive battle".[22]

Between May 25 and 28, Pakistan conducted 3 missile tests. India reviewed its nuclear capability to strike back.[16] On 7 June the Pakistan Air Force shot down an Indian unmanned aerial vehicle near Lahore.[23]

Threat of nuclear war

As both India and Pakistan are armed with nuclear weapons, the possibility a conventional war could escalate into a nuclear one was raised several times during the standoff. Various statements on this subject were made by Indian and Pakistani officials during the conflict, mainly concerning a no first use policy. Indian External Affairs Minister Jaswant Singh said on 5 June that India would not use nuclear weapons first,[24] while Musharraf said on 5 June he would not renounce Pakistan's right to use nuclear weapons first.[25] There was also concern that a 6 June 2002 asteroid explosion over Earth, known as the Eastern Mediterranean Event, could have caused a nuclear conflict had it exploded over India or Pakistan.[26]

Diplomacy

Vajpayee contacted the leaders of the global community including Bush, Blair, Russian President Vladimir Putin and French President Jacques Chirac and informed them Musharraf could not deliver on his January 12 speech and the patience of the country was running out. In the diplomacy that followed, Bush, Putin, Blair and Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi requested Vajpayee to avoid taking the extreme step. The global community informed India that it would negotiate with Musharraf to clarify his position on stopping of the cross-border infiltration.[16]

Attempts to defuse the situation continued. The Russian President Vladimir Putin tried to mediate a solution, but in vain.[27]

Restraint was urged by the global community as there were fears that Pakistan would proceed to use its nuclear weapons in the face to counter its conventional asymmetry as compared to the Indian armed forces. In April, in an interview to German magazine Der Spiegel Musharraf had already hinted that he was willing to use nukes against India. Pakistan's nuclear threats led to US Secretary of State Powell contacting Musharraf at five occasions in the last week of May and reading the riot act.[16]

On 5 June American Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage visited Pakistan. He asked Musharraf if he would "permanently" end cross-border infiltration and help to dismantle the infrastructure used for terrorism. On June 6 Musharraf 's commitment was conveyed to Powell, and to India after his arrival. On June 10, Powell announced Musharraf's promise to the global community. After which India called off its strike plans.[16]

A full-frontal invasion would have translated into war. Political logic implied it was better to give another chance to Musharraf. The military build-up on the border by India in January and June had forced both the international community and Pakistan into action.[16]

July-August strikes

On July 29, 2002 for the first time after the end of Kargil war India used air power to attack positions held by the Pakistani forces at Loonda Post on the Indian side of the Line of Control in the Machil sector. Eight IAF Mirage 2000 H aircraft dropped precision-guided bombs weighing 1,000-pounds to destroy four bunkers that were occupied by Pakistan. The forward trenches prepared by Indian troops in earlier years were also occupied by the Pakistani forces and 155-millimetre Bofors howitzers were used to hit them. According to Indian military intelligence officials at least 28 Pakistani soldiers were killed in the fighting. The air assault was conducted in daylight and to demonstrate India's willingness to escalate the conflict in response to provocations.[28]

Pakistani army troops stationed near the post in Kupwara sector's Kel area of the LOC had been shelling the Indian positions across the LOC. India suspected a troop build up situation near the border post that was similar to Kargil. Indian army planned a retaliation by sending troops to attack the Pakistani posts. After deliberations with the then Army Chief, General Sundararajan Padmanabhan, the plan was modified and instead of only a ground assault, the decision was made to first attack Pakistani positions using the IAF jets followed by a ground assault by the Indian Special Forces. At 1:30 pm on 2 August, IAF's No. 1 Tiger Squadron of Mirage 2000 H fighter aircraft loaded with laser guided weapons bombed the Pakistani bunkers located in the Kel. The attack destroyed the bunkers with an unknown number of casualty. Pakistani troops then opened heavy artillery fire on the Indian posts. The Indian Special forces then followed up to kill the remaining Pakistani soldiers.[29][16]

Easing of Tension

While tensions remained high throughout the next few months, both governments began easing the situation in Kashmir. By October 2002, India had begun to demobilize their troops along her border and later Pakistan did the same, and in November 2003 a cease-fire between the two nations was signed.[30]

Casualties

The standoff inflicted heavy casualties. The total Indian casualties were 789–1,874 killed. Many accidents during the mobilisation were due to the poor quality of mines and fuses[2][3] Around 100 of these fatalities were from mine laying operations. Artillery duels with Pakistan, vehicle accidents, and other incidents make up the rest.[2]

Cost of standoff

The Indian cost for the buildup was ₹216 billion (US$3.0 billion) while Pakistan's was $1.4 billion.[31] The standoff led to a total of 155,000 Indians and 45,000 Pakistanis displaced.[32]

Development of Cold Start

After the deescalation and the substantial diplomatic mediation, the Indian government, however, learned the seriousness of the military suspension by Pakistan in the region. Adjustments and development on offensive doctrine, Cold Start, was carried out by India as an aftermath of the war.

Published Account

Books

- Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy written by the former National Security Advisor of India, Shivshankar Menon. In his book Menon mentioned that the reason why India did not immediately attacked Pakistan was, after the examination of the options by the leadership of the government, it was concluded by the decision makers that, "more was to be gained from not attacking Pakistan than from attacking it".[33]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Kashmir Crisis Archived 11 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Global Security.org

- 1 2 3 "Op Parakram claimed 798 soldiers". The imes Of India. 31 July 2003. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- 1 2 India suffered 1,874 casualties without fighting a war Archived 19 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine., THE TIMES OF INDIA.

- ↑ Rajesh M. Basrur (14 December 2009). "The lessons of Kargil as learned by India". In Peter R. Lavoy. Asymmetric Warfare in South Asia: The Causes and Consequences of the Kargil Conflict (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-521-76721-7. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ↑ "Who will strike first" Archived 5 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine., The Economist, 20 December 2001.

- ↑ Jamal Afridi (9 July 2009). "Kashmir Militant Extremists". Council Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

Pakistan denies any ongoing collaboration between the ISI and militants, stressing a change of course after 11 September 2001.

- ↑ Perlez, Jane (29 November 2008). "Pakistan Denies Any Role in Mumbai Attacks". Mumbai (India);Pakistan: NYTimes.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ "Attack on Indian parliament heightens danger of Indo-Pakistan war". Wsws.org. 20 December 2001. Archived from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ↑ "India to withdraw troops from Pak border" Archived 30 November 2003 at the Wayback Machine., Times of India, 16 October 2002.

- ↑ "Pakistan to withdraw front-line troops" Archived 14 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine., BBC, 17 October 2002.

- ↑ "Parliament attack: Advani points towards neighbouring country" Archived 6 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine., Rediff, 14 December 2001.

- ↑ "Govt blames LeT for Parliament attack, asks Pak to restrain terrorist outfits" Archived 13 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine., Rediff, 14 December 2001.

- ↑ "Pakistan forces put on high alert: Storming of parliament" Archived 14 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine., Dawn (newspaper), 15 December 2001.

- ↑ "Musharraf vows to stop terror activity in Pakistan". USA Today. 22 June 2002. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ↑ "Gen. Padmanabhan mulls over lessons of Operation Parakram". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 6 February 2004. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 "Twice in 2002, India was on the verge of striking against Pakistan. Here's why it didn't". Cover Story. India Today. 23 December 2002. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ↑ Pakistan, India 'move missiles' to border Archived 6 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. CNN, 26 December 2001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The Stand-off" Archived 18 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine., The New Yorker, 13 February 2006.

- ↑ Musharraf declares war on extremism Archived 7 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine., BBC, 12 January 2002.

- ↑ "India expels Pakistan's ambassador" Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine., CBC.ca, 18 May 2002.

- ↑ "Six more Pak soldiers killed" Archived 5 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine., The Tribune, 21 May 2002.

- ↑ "Indian PM calls for 'decisive battle' over Kashmir" Archived 4 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine., The Guardian, Wednesday 22 May 2002. Retrieved on 7 February 2013.

- ↑ "IAF's Searcher-II Loss on June 07, 2002". Vayu-sena-aux.tripod.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ "India will not use nuclear weapons first: Singh". BNET. 3 June 2002. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 2012-03-20.

- ↑ Irish Examiner – 2002/06/05: "Musharraf refuses to renounce first use of nuclear weapons" Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine., Irish Examiner, 5 June 2002

- ↑ "Near-Earth Objects Pose Threat, General Says". Spacedaily.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2002. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ "Putin Attempts to Mediate India-Pakistan Tensions" Archived 10 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine., VOA, 3 June 2002. Retrieved on 7 February 2013.

- ↑ When Pakistan took Loonda Post Frontline Volume 19 - Issue 18, August 31 - September 13, 2002

- ↑ "EXCLUSIVE: In 2002, India's Fighter Jets Hit Pakistan In A Surgical Strike You've Never Been Told About". Huffington Post. 27 January 2017. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ↑ "India-Pakistan Ceasefire Agreement" Archived 11 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine., NDTV. Retrieved on 7 February 2013.

- ↑ Aditi Phadnis (16 January 2003). "Parakram cost put at Rs 6,500 crore". Rediff.com India Limited. Archived from the original on 3 February 2003. Retrieved 2012-03-20.

- ↑ "The cost of conflict-II Beyond the direct cost of war". The News International. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ↑ Menon, Shivshankar (2016). Choices: Inside the Making of Indian Foreign Policy (Excerpt from The Hindu ed.). Penguin Random House India. ISBN 978-0670089239. Retrieved 8 September 2018.