Sikkim

| Sikkim | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | ||

Kanchenjunga, the third highest mountain in the world, lies partially in Sikkim | ||

| ||

| ||

| Coordinates (Gangtok): 27°20′N 88°37′E / 27.33°N 88.62°ECoordinates: 27°20′N 88°37′E / 27.33°N 88.62°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| Admission to Union † | 16 May 1975 | |

| Capital | Gangtok | |

| Largest city | Gangtok | |

| Districts | 4 | |

| Government | ||

| • Governor | Ganga Prasad | |

| • Chief Minister | Pawan Chamling (SDF) | |

| • Legislature | Unicameral (32 seats) | |

| • Parliamentary constituency |

Rajya Sabha 1 Lok Sabha 1 | |

| • High Court | Sikkim High Court | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 7,096 km2 (2,740 sq mi) | |

| Area rank | 28th | |

| Population (2011)[1] | ||

| • Total | 610,577 | |

| • Rank | 29th | |

| • Density | 86/km2 (220/sq mi) | |

| Demonym(s) | Sikkimese | |

| Languages[2][3] | ||

| • Official | English | |

| • Additional official | ||

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) | |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-SK | |

| HDI |

| |

| HDI rank | 7th (2005) | |

| Literacy | 82.6% (13th) | |

| Website | Sikkim.gov.in | |

| † Assembly of Sikkim abolished monarchy and resolved to be a constituent unit of India. A referendum was held on these issues and majority of the voters voted yes. On 15 May 1975 the President of India ratified a constitutional amendment that made Sikkim the 22nd state of India. | ||

| Emblem |

|

|---|---|

| Animal |

|

| Bird |

|

| Flower |

|

| Tree |

|

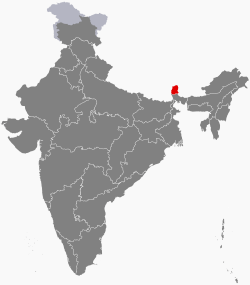

Sikkim (/ˈsɪkɪm/) is a state in northeast India. It borders Tibet in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Nepal in the west, and West Bengal in the south. Sikkim is also located close to India's Siliguri Corridor near Bangladesh. Sikkim is the least populous and second smallest among the Indian states. A part of the Eastern Himalaya, Sikkim is notable for its biodiversity, including alpine and subtropical climates, as well as being a host to Kanchenjunga, the highest peak in India and third highest on Earth. Sikkim's capital and largest city is Gangtok. Almost 35% of the state is covered by the Khangchendzonga National Park.[7]

The Kingdom of Sikkim was founded by the Namgyal dynasty in the 17th century. It was ruled by a Buddhist priest-king known as the Chogyal. It became a princely state of British India in 1890. After 1947, Sikkim continued its protectorate status with the republic of India. It enjoyed the highest literacy rate and per capita income among Himalayan states. In 1973, anti-royalist riots took place in front of the Chogyal's palace. In 1975, the monarchy was deposed by the people. A referendum in 1975 led to Sikkim joining India as its 22nd state.[8]

Modern Sikkim is a multiethnic and multilingual Indian state. Sikkim has 11 official languages: Nepali, Sikkimese, Lepcha, Tamang, Limbu, Newari, Rai, Gurung, Magar, Sunwar and English.[2][3][9] English is taught in schools and used in government documents. The predominant religions are Hinduism and Vajrayana Buddhism. Sikkim's economy is largely dependent on agriculture and tourism, and as of 2014 the state had the third-smallest GDP among Indian states,[10] although it is also among the fastest-growing.[10][11]

Sikkim accounts for the largest share of cardamom production in India, and is the world's second largest producer of the spice after Guatemala. Sikkim achieved its ambition to convert its agriculture to fully organic over the interval 2003 to 2016, the first state in India to achieve this distinction.[12][13][14][15] It is also among India's most environmentally conscious states, having banned plastic water bottles and styrofoam products.[16][17]

Toponymy

The origin theory of the name Sikkim is that it is a combination of two Limbu words: su, which means "new", and khyim, which means "palace" or "house".[18] The Tibetan name for Sikkim is Drenjong (Wylie-transliteration: ´bras ljongs), which means "valley of rice",[19] while the Bhutias call it Beyul Demazong, which means '"the hidden valley of rice".[20] According to the folklore, after establishing Rabdentse as his new capital Bhutia king Tensung Namgyal built a palace and asked his Limbu Queen to name it. The Lepcha people, the original inhabitants of Sikkim, called it Nye-mae-el, meaning "paradise".[20] In historical Indian literature, Sikkim is known as Indrakil, the garden of the war god Indra.[21]

History

The Lepchas are considered to be the earliest inhabitants of Sikkim.[22] However the Limbus and the Magars also lived in the inaccessible parts of West and South districts as early as the Lepchas perhaps lived in the East and North districts. [23] The Buddhist saint Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche, is said to have passed through the land in the 8th century.[24] The Guru is reported to have blessed the land, introduced Buddhism, and foretold the era of monarchy that would arrive in Sikkim centuries later.

Foundation of the monarchy

According to legend, Khye Bumsa, a 14th-century prince from the Minyak House in Kham in eastern Tibet, received a divine revelation instructing him to travel south to seek his fortunes. A fifth-generation descendant of Khye Bumsa, Phuntsog Namgyal, became the founder of Sikkim's monarchy in 1642, when he was consecrated as the first Chogyal, or priest-king, of Sikkim by the three venerated lamas at Yuksom.[25] Phuntsog Namgyal was succeeded in 1670 by his son, Tensung Namgyal, who moved the capital from Yuksom to Rabdentse (near modern Pelling). In 1700, Sikkim was invaded by the Bhutanese with the help of the half-sister of the Chogyal, who had been denied the throne. The Bhutanese were driven away by the Tibetans, who restored the throne to the Chogyal ten years later. Between 1717 and 1733, the kingdom faced many raids by the Nepalese in the west and Bhutanese in the east, culminating with the destruction of the capital Rabdentse by the Nepalese.[26] In 1791, China sent troops to support Sikkim and defend Tibet against the Gorkha Kingdom. Following the subsequent defeat of Gorkha, the Chinese Qing dynasty established control over Sikkim.[27]

During the British Raj

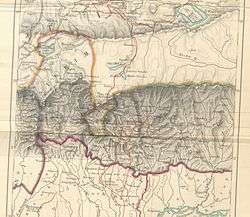

Following the beginning of British rule in neighbouring India, Sikkim allied with Britain against their common adversary, Nepal. The Nepalese attacked Sikkim, overrunning most of the region including the Terai. This prompted the British East India Company to attack Nepal, resulting in the Gurkha War of 1814.[29] Treaties signed between Sikkim and Nepal resulted in the return of the territory annexed by the Nepalese in 1817. However, ties between Sikkim and the British weakened when the latter began taxation of the Morang region. In 1849, two British physicians, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker and Dr. Archibald Campbell, the latter being in charge of relations between the British and Sikkimese governments, ventured into the mountains of Sikkim unannounced and unauthorised.[30] The doctors were detained by the Sikkimese government, leading to a punitive British expedition against the kingdom, after which the Darjeeling district and Morang were annexed to British India in 1853. The invasion led to the Chogyal of Sikkim becoming a titular ruler under the directive of the British governor.[31]

Sikkim became a British protectorate in the later decades of the 19th century, formalised by a convention signed with China in 1890.[32][33] [34] Sikkim was gradually granted more sovereignty over the next three decades,[35] and became a member of the Chamber of Princes, the assembly representing the rulers of the Indian princely states, in 1922.[34]

Indian protectorate and statehood

.svg.png)

.jpg)

Prior to the Indian independence, Jawaharlal Nehru, as the Vice President of the Executive Council, pushed through a resolution in the Indian Constituent Assembly to the effect that Sikkim and Bhutan, as Himalayan states, were not 'Indian states' and their future should be negotiated separately.[36] A standstill agreement was signed in February 1948.[37]

Meanwhile, the Indian independence and its move to democracy spurred a fledgling political movement in Sikkim, giving rise to the formation of Sikkim State Congress (SSC). The party sent a plate of demands to the palace, including a demand for accession to India. The palace attempted to defuse the movement by appointing three secretaries from the SSC to the government and sponsoring a counter-movement in the name of Sikkim National Party, which opposed accession to India.[38]

The demand for responsible government continued and the SSC launched a civil disobedience movement. The Chogyal Palden Thondup Namgyal asked India for help in quelling the movement, which was offered in the form of a small military police force and an Indian Dewan. In 1950, a treaty was agreed between India and Sikkim which gave Sikkim the status of an Indian protectorate. Sikkim came under the suzerainty of India, which controlled its external affairs, defence, diplomacy and communications.[39] In other respects, Sikkim retained administrative autonomy.

A state council was established in 1953 to allow for constitutional government under the Chogyal. Despite pressures from an India "bent on annexation", Chogyal Palden Thondup Namgyal was able to preserve autonomy and shape a "model Asian state" where the literacy rate and per capita income were twice as high as neighbouring Nepal, Bhutan and India.[40] Meanwhile, the Sikkim National Congress demanded fresh elections and greater representation for Nepalis in Sikkim. People marched on the palace against the monarchy.[40] In 1973, anti-royalist riots took place in front of the Chogyal's palace.

In 1975, the Prime Minister of Sikkim appealed to the Indian Parliament for Sikkim to become a state of India. In April of that year, the Indian Army took over the city of Gangtok and disarmed the Chogyal's palace guards. Thereafter, a referendum was held in which 97.5 per cent of voters supported abolishing the monarchy, effectively approving union with India. India is said to have stationed 20,000–40,000 troops in a country of only 200,000 during the referendum.[41] On 16 May 1975, Sikkim became the 22nd state of the Indian Union, and the monarchy was abolished.[42] To enable the incorporation of the new state, the Indian Parliament amended the Indian Constitution. First, the 35th Amendment laid down a set of conditions that made Sikkim an "Associate State", a special designation not used by any other state. A month later, the 36th Amendment repealed the 35th Amendment, and made Sikkim a full state, adding its name to the First Schedule of the Constitution.[43]

Recent history

In 2000, the seventeenth Karmapa, Urgyen Trinley Dorje, who had been confirmed by the Dalai Lama and accepted as a tulku by the Chinese government, escaped from Tibet, seeking to return to the Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim. Chinese officials were in a quandary on this issue, as any protests to India would mean an explicit endorsement of India's governance of Sikkim, which China still recognised as an independent state occupied by India. The Chinese government eventually recognised Sikkim as an Indian state in 2003, on the condition that India officially recognise Tibet as a part of China;[44] New Delhi had originally accepted Tibet as a part of China in 1953 during the government of Jawaharlal Nehru.[45] The 2003 agreement led to a thaw in Sino-Indian relations,[46] and on 6 July 2006, the Sikkimese Himalayan pass of Nathu La was opened to cross-border trade, becoming the first open border between India and China.[47] The pass, which had previously been closed since the 1962 Sino-Indian War, was an offshoot of the ancient Silk Road.[47]

On 18 September 2011, a magnitude 6.9Mw earthquake struck Sikkim, killing at least 116 people in the state and in Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Tibet.[48] More than 60 people died in Sikkim alone, and the city of Gangtok suffered significant damage.[49]

Geography

Nestling in the Himalayan mountains, the state of Sikkim is characterised by mountainous terrain. Almost the entire state is hilly, with an elevation ranging from 280 metres (920 ft) in south at border with West Bengal to 8,586 metres (28,169 ft) in northern peaks near Nepal and Tibet. The summit of Kangchenjunga, the world's third-highest peak, is the state's highest point, situated on the border between Sikkim and Nepal.[50] For the most part, the land is unfit for agriculture because of the rocky, precipitous slopes. However, some hill slopes have been converted into terrace farms.

_show_the_high%2C_arid%2C_Tibetan_Plateau_in_Asia._Tibet_lies_north_of_the_Himalaya_Mountains_in_Nepal---Tibet.A2002343.0445.1km.jpg)

Numerous snow-fed streams have carved out river valleys in the west and south of the state. These streams combine into the major Teesta River and its tributary, the Rangeet, which flow through the state from north to south.[51] About a third of the state is heavily forested. The Himalayan mountains surround the northern, eastern and western borders of Sikkim. The Lower Himalayas, lying in the southern reaches of the state, are the most densely populated.

The state has 28 mountain peaks, more than 80 glaciers,[52] 227 high-altitude lakes (including the Tsongmo, Gurudongmar and Khecheopalri Lakes), five major hot springs, and more than 100 rivers and streams. Eight mountain passes connect the state to Tibet, Bhutan and Nepal.[53]

Sikkim's hot springs are renowned for their medicinal and therapeutic values. Among the state's most notable hot springs are those at Phurchachu, Yumthang, Borang, Ralang, Taram-chu and Yumey Samdong. The springs, which have a high sulphur content, are located near river banks; some are known to emit hydrogen.[54] The average temperature of the water in these hot springs is 50 °C (122 °F).[55]

Geology

The hills of Sikkim mainly consist of gneiss and schist[56] which weather to produce generally poor and shallow brown clay soils. The soil is coarse, with large concentrations of iron oxide; it ranges from neutral to acidic and is lacking in organic and mineral nutrients. This type of soil tends to support evergreen and deciduous forests.[57]

The rock consists of phyllites and schists, and is highly susceptible to weathering and erosion. This, combined with the state's heavy rainfall, causes extensive soil erosion and the loss of soil nutrients through leaching. As a result, landslides are frequent, often isolating rural towns and villages from the major urban centres.[58]

Climate

The state has five seasons: winter, summer, spring, autumn, and a monsoon season between June and September. Sikkim's climate ranges from sub-tropical in the south to tundra in the north. Most of the inhabited regions of Sikkim experience a temperate climate, with temperatures seldom exceeding 28 °C (82 °F) in summer. The average annual temperature for most of Sikkim is around 18 °C (64 °F).

Sikkim is one of the few states in India to receive regular snowfall. The snow line ranges from 6,100 metres (20,000 ft) in the south of the state to 4,900 metres (16,100 ft) in the north.[59] The tundra-type region in the north is snowbound for four months every year, and the temperature drops below 0 °C (32 °F) almost every night.[54] In north-western Sikkim, the peaks are frozen year-round;[60] because of the high altitude, temperatures in the mountains can drop to as low as −40 °C (−40 °F) in winter.

During the monsoon, heavy rains increase the risk of landslides. The record for the longest period of continuous rain in Sikkim is 11 days. Fog affects many parts of the state during winter and the monsoons, making transportation perilous.[61]

Government and politics

According to the Constitution of India, Sikkim has a parliamentary system of representative democracy for its governance; universal suffrage is granted to state residents. The government structure is organised into three branches:

- Executive: As with all states of India, a governor stands at the head of the executive power of state, just as the president is the head of the executive power in the Union, and is appointed by the President of India. The governor's appointment is largely ceremonial, and his or her main role is to oversee the swearing-in of the Chief Minister. The Chief Minister, who holds the real executive powers, is the head of the party or coalition garnering the largest majority in the state elections. The governor also appoints cabinet ministers on the advice of the Chief Minister.

- Legislature: Sikkim has a unicameral legislature, the Sikkim Legislative Assembly, like most other Indian states. Its state assembly has 32 seats, including one reserved for the Sangha. Sikkim is allocated one seat in each of the two chambers of India's national bicameral legislature, the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha.

- Judiciary: The judiciary consists of the Sikkim High Court and a system of lower courts. The High Court, located at Gangtok, has a Chief Justice along with two permanent justices. The Sikkim High Court is the smallest state high court in the country.[62]

In 1975, after the abrogation of Sikkim's monarchy, the Indian National Congress gained a majority in the 1977 elections. In 1979, after a period of instability, a popular ministry headed by Nar Bahadur Bhandari, leader of the Sikkim Sangram Parishad Party, was sworn in. Bhandari held on to power in the 1984 and 1989 elections. In the 1994 elections, Pawan Kumar Chamling of the Sikkim Democratic Front became the Chief Minister of the state. Chamling and his party have since held on to power by winning the 1999, 2004, 2009 and 2014 elections.[31][63][64] Currently, the Governor of Sikkim is Shriniwas Dadasaheb Patil.[65]

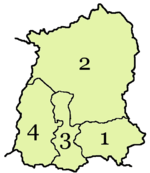

Subdivisions

1. East Sikkim

2. North Sikkim

3. South Sikkim

4. West Sikkim

Sikkim has four districts – East Sikkim, North Sikkim, South Sikkim and West Sikkim. The district capitals are Gangtok, Mangan, Namchi and Gyalshing respectively.[66] These four districts are further divided into subdivisions; Pakyong and Rongli are the subdivisions of the East district, Soreng is the subdivision of the West district, Chungthang is the subdivision of the North district and Ravongla is the subdivision of the South district.[67]

Each of Sikkim's districts is overseen by a Central Government appointee, the district collector, who is in charge of the administration of the civilian areas of the district. The Indian Army has control over a large part of the state, as Sikkim forms part of a sensitive border area with China. Many areas are restricted to foreigners, and official permits are needed to visit them.[68]

Flora and fauna

Sikkim is situated in an ecological hotspot of the lower Himalayas, one of only three among the ecoregions of India.[70] The forested regions of the state exhibit a diverse range of fauna and flora. Owing to its altitudinal gradation, the state has a wide variety of plants, from tropical species to temperate, alpine and tundra ones, and is perhaps one of the few regions to exhibit such a diversity within such a small area. Nearly 81 per cent of the area of Sikkim comes under the administration of its forest department.[71]

Sikkim is home to around 5,000 species of flowering plants, 515 rare orchids, 60 primula species, 36 rhododendron species, 11 oak varieties, 23 bamboo varieties, 16 conifer species, 362 types of ferns and ferns allies, 8 tree ferns, and over 900 medicinal plants.[70] A variant of the Poinsettia, locally known as "Christmas Flower", can be found in abundance in the mountainous state. The Noble Dendrobium is the official flower of Sikkim, while the rhododendron is the state tree.[72]

Orchids, figs, laurel, bananas, sal trees and bamboo grow in the Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests of the lower altitudes of Sikkim. In the temperate elevations above 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) there are Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests, where oaks, chestnuts, maples, birches, alders, and magnolias grow in large numbers, as well as Himalayan subtropical pine forests, dominated by Chir pine. Alpine-type vegetation is typically found between an altitude of 3,500 to 5,000 metres (11,500 to 16,400 ft). In lower elevations are found juniper, pine, firs, cypresses and rhododendrons from the Eastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests. Higher up are Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows, home to a broad variety of rhododendrons and wildflowers.

The fauna of Sikkim include the snow leopard,[73] musk deer, Himalayan tahr, red panda, Himalayan marmot, Himalayan serow, Himalayan goral, muntjac, common langur, Asian black bear, clouded leopard,[74] marbled cat, leopard cat,[75] dhole, Tibetan wolf, hog badger, binturong, and Himalayan jungle cat. Among the animals more commonly found in the alpine zone are yaks, mainly reared for their milk, meat, and as a beast of burden.

The avifauna of Sikkim include the impeyan pheasant, crimson horned pheasant, snow partridge, Tibetan snowcock, bearded vulture and griffon vulture, as well as golden eagles, quails, plovers, woodcocks, sandpipers, pigeons, Old World flycatchers, babblers and robins. Sikkim has more than 550 species of birds, some of which have been declared endangered.[76]

Sikkim also has a rich diversity of arthropods, many of which remain unstudied; the most studied Sikkimese arthropods are butterflies. Of the approximately 1,438 butterfly species found in the Indian subcontinent, 695 have been recorded in Sikkim.[77] These include the endangered Kaiser-i-hind, the Yellow Gorgon and the Bhutan Glory.[78]

Economy

Sikkim's nominal state gross domestic product (GDP) was estimated at US$1.57 billion in 2014, constituting the third-smallest GDP among India's 28 states.[10] The state's economy is largely agrarian, based on the terraced farming of rice and the cultivation of crops such as maize, millet, wheat, barley, oranges, tea and cardamom.[79][80] Sikkim produces more cardamom than any other Indian state, and is home to the largest cultivated area of cardamom.[81]

Because of its hilly terrain and poor transport infrastructure, Sikkim lacks a large-scale industrial base. Brewing, distilling, tanning and watchmaking are the main industries, and are mainly located in the southern regions of the state, primarily in the towns of Melli and Jorethang. In addition, a small mining industry exists in Sikkim, extracting minerals such as copper, dolomite, talc, graphite, quartzite, coal, zinc and lead.[82] Despite the state's minimal industrial infrastructure, Sikkim's economy has been among the fastest-growing in India since 2000; the state's GDP expanded by 89.93 per cent in 2010 alone.[83] In 2003, Sikkim decided to convert fully to organic farming statewide, and achieved this goal in 2015, becoming India's first "organic state".[13][14][15][12]

In recent years, the government of Sikkim has extensively promoted tourism. As a result, state revenue has increased 14 times since the mid-1990s.[84] Sikkim has furthermore invested in a fledgling gambling industry, promoting both casinos and online gambling. The state's first casino, the Casino Sikkim, opened in March 2009, and the government subsequently issued a number of additional casino licences and online sports betting licenses.[85][86] The Playwin lottery has been a notable success in the state.[87][88]

The opening of the Nathu La pass on 6 July 2006, connecting Lhasa, Tibet, to India, was billed as a boon for Sikkim's economy. Trade through the pass remains hampered by Sikkim's limited infrastructure and government restrictions in both India and China, though the volume of traded goods has been steadily increasing.[89][90]

Transport

Air

Sikkim did not have any operational airport for a long time because of its rough terrain. However in October 2018, Pakyong Airport, the state's first airport, located at a distance of 30 km (19 mi) from Gangtok, become operational after a four-year delay.[91][92] It has been constructed by the Airports Authority of India on 200 acres of land. At an altitude of 4,700 feet (1,400 m) above sea level, it is one of the five highest airports in India.[93][94] The airport is capable of operating ATR aircraft.[95]

Before October 2018, the closest operational airport to Sikkim was Bagdogra Airport, near Siliguri town in northern West Bengal. The airport is located about 124 km (77 mi) from Gangtok, and frequent buses connect the two.[96] A daily helicopter service run by the Sikkim Helicopter Service connects Gangtok to Bagdogra; the flight is thirty minutes long, operates only once a day, and can carry four people.[63] The Gangtok helipad is the only civilian helipad in the state.

Roads

National highway 10 (NH 10) links Siliguri to Gangtok. Sikkim National Transport runs bus and truck services. Privately run bus, tourist taxi and jeep services operate throughout Sikkim, and also connect it to Siliguri. A branch of the highway from Melli connects western Sikkim. Towns in southern and western Sikkim are connected to the hill stations of Kalimpong and Darjeeling in northern West Bengal.[97] The state is furthermore connected to Tibet by the mountain pass of Nathu La.

NH 10 was numbered NH 31A before renumbering of all national highways) in India.

Rail

Sikkim lacks significant railway infrastructure. The closest major railway stations are Siliguri and New Jalpaiguri in neighbouring West Bengal.[98] However, the New Sikkim Railway Project has been launched to connect the town of Rangpo in Sikkim with Sevoke on the West Bengal border.[99] The five-station line is intended to support both economic development and Indian Army operations, and was initially planned to be completed by 2015,[100][101] though as of 2013 its construction has met with delays.[102] In addition, the Ministry of Railways proposed plans in 2010 for railway lines linking Mirik to Ranipool.[103]

Infrastructure

Sikkim's roads are maintained by the Border Roads Organisation (BRO), an offshoot of the Indian Army. The roads in southern Sikkim are in relatively good condition, landslides being less frequent in this region. The state government maintains 1,857 kilometres (1,154 mi) of roadways that do not fall under the BRO's jurisdiction.[67]

Sikkim receives most of its electricity from 19 hydroelectric power stations.[84] Power is also obtained from the National Thermal Power Corporation and Power Grid Corporation of India.[104] By 2006, the state had achieved 100 per cent rural electrification.[105] However, the voltage remains unstable and voltage stabilisers are needed. Per capita consumption of electricity in Sikkim was approximately 182 kWh in 2006. The state government has promoted biogas and solar power for cooking, but these have received a poor response and are used mostly for lighting purposes.[106] In 2005, 73.2 per cent of Sikkim's households were reported to have access to safe drinking water,[67] and the state's large number of mountain streams assures a sufficient water supply.

On 8 December 2008, it was announced that Sikkim had become the first state in India to achieve 100 per cent sanitation coverage, becoming completely free of public defecation, thus attaining the status of "Nirmal State".[107][108]

Demographics

| Population growth history | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1951 | 138,000 | — | |

| 1961 | 162,000 | 17.4% | |

| 1971 | 210,000 | 29.6% | |

| 1981 | 316,000 | 50.5% | |

| 1991 | 406,000 | 28.5% | |

| 2001 | 541,000 | 33.3% | |

| 2011 | 607,688 | 12.3% | |

| Sources: Census of India[1][109] | |||

Sikkim is India's least populous state, with 610,577 inhabitants according to the 2011 census.[1] Sikkim is also one of the least densely populated Indian states, with only 86 persons per square kilometre. However, it has a high population growth rate, averaging 12.36% per cent between 2001 and 2011. The sex ratio is 889 females per 1,000 males, with a total of 321,661 males and 286,027 females recorded in 2011. With around 98,000 inhabitants as of 2011, the capital Gangtok is the most significant urban area in the mostly rural state; in 2005, the urban population in Sikkim constituted around 11.06 per cent of the total.[67] In 2011, the average per capita income in Sikkim stood at ₹81,159 (US$1,305).[110]

Languages

Nepali is the lingua franca of Sikkim, while Sikkimese (Bhutia) and Lepcha are spoken in certain areas. English is also spoken and understood in most of Sikkim. Other languages include Dzongkha, Groma, Gurung, Limbu, Magar, Majhi, Majhwar, Nepal Bhasa, Rai, Sherpa, Sunuwar, Tamang, Thulung, Tibetan, and Yakha.[114]

The major languages spoken as per census 2001 are Nepali (338,606), Sikkimese (41,825), Hindi (36,072), Lepcha (35,728), Limbu (34,292), Sherpa (13,922), Tamang (10,089), etc.

Ethnicity

The majority of Sikkim's residents are of Nepali ethnic origin.[115] The native Sikkimese consist of the Bhutias, who migrated from the Kham district of Tibet in the 14th century, and the Lepchas, who are believed to have migrated from the Far East. Tibetans reside mostly in the northern and eastern reaches of the state. Migrant resident communities include Biharis, Bengalis and Marwaris, who are prominent in commerce in South Sikkim and Gangtok.[116]

Religion

Hinduism is the state's major religion and is practised mainly by ethnic Nepalis; an estimated 57.8 per cent of the total population are adherents of the religion. There exist many Hindu temples. Kirateshwar Mahadev Temple is very popular, since it consists of the chardham altogether.

Vajrayana Buddhism, which accounts for 27.3 per cent of the population, is Sikkim's second-largest, yet most prominent religion. Prior to Sikkim's becoming a part of the Indian Union, Vajrayana Buddhism was the state religion under the Chogyal. Sikkim has 75 Buddhist monasteries, the oldest dating back to the 1700s.[118] The public and visual aesthetics of Sikkim are executed in shades of Vajrayana Buddhism and Buddhism plays a significant role in public life, even among Sikkim's majority Nepali Hindu population.

Christians in Sikkim are mostly descendants of Lepcha people who were converted by British missionaries in the late 19th century, and constitute around 10 per cent of the population. As of 2014, the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Sikkim is the largest Christian denomination in Sikkim.[119] Other religious minorities include Muslims of Bihari ethnicity and Jains, who each account for roughly one per cent of the population.[120] The traditional religions of the native Sikkimese account for much of the remainder of the population.

Although tensions between the Lepchas and the Nepalese escalated during the merger of Sikkim with India in the 1970s, there has never been any major degree of communal religious violence, unlike in other Indian states.[121][122] The traditional religion of the Lepcha people is Mun, an animist practice which coexists with Buddhism and Christianity.[123]

Culture

Festivals and holidays

Sikkim's Nepalese majority celebrate all major Hindu festivals, including Diwali and Dussera. Traditional local festivals, such as Maghe Sankranti and Bhimsen Puja, are popular.[124] Losar, Loosong, Saga Dawa, Lhabab Duechen, Drupka Teshi and Bhumchu are among the Buddhist festivals celebrated in Sikkim. During the Losar (Tibetan New Year), most offices and educational institutions are closed for a week.[125]

Sikkimese Muslims celebrate Eid ul-Fitr and Muharram.[126] Christmas has been promoted in Gangtok to attract tourists during the off-season.[127]

Western rock music and Indian pop have gained a wide following in Sikkim. Indigenous Nepali rock and Lepcha music are also popular.[128] Sikkim's most popular sports are football and cricket, although hang gliding and river rafting have grown popular as part of the tourism industry.[129]

Cuisine

Noodle-based dishes such as thukpa, chow mein, thenthuk, fakthu, gyathuk and wonton are common in Sikkim. Momos – steamed dumplings filled with vegetables, buffalo meat or pork and served with soup – are a popular snack.[130]

Beer, whiskey, rum and brandy are widely consumed in Sikkim,[131] as is tongba, a millet-based alcoholic beverage that is popular in Nepal and Darjeeling. Sikkim has the third-highest per capita alcoholism rate amongst all Indian states, behind Punjab and Haryana.[132]

Media

The southern urban areas of Sikkim have English, Nepali and Hindi daily newspapers. Nepali-language newspapers, as well as some English newspapers, are locally printed, whereas Hindi and English newspapers are printed in Siliguri. Important local dailies and weeklies include Hamro Prajashakti (Nepali daily), Himalayan Mirror (English daily), the Samay Dainik, Sikkim Express (English), Kanchanjunga Times (Nepali weekly), Pragya Khabar (Nepali weekly) and Himali Bela.[133] Furthermore, the state receives regional editions of national English newspapers such as The Statesman, The Telegraph, The Hindu and The Times of India. Himalaya Darpan, a Nepali daily published in Siliguri, is one of the leading Nepali daily newspapers in the region. The Sikkim Herald is an official weekly publication of the government. Online media covering Sikkim include the Nepali newspaper Himgiri, the English news portal Haalkhabar and the literary magazine Tistarangit. Avyakta, Bilokan, the Journal of Hill Research, Khaber Khagaj, Panda, and the Sikkim Science Society Newsletter are among other registered publications.[134]

Internet cafés are well established in the district capitals, but broadband connectivity is not widely available. Satellite television channels through dish antennae are available in most homes in the state. Channels served are largely the same as those available in the rest of India, although Nepali-language channels are also available. The main service providers include Dish TV, Doordarshan and Nayuma.

Education

In 2011, Sikkim's adult literacy rate was 82.2 per cent: 87.29 per cent for males and 76.43 per cent for females.[135] There are a total of 1,157 schools in the state, including 765 schools run by the state government, seven central government schools and 385 private schools.[136] There is one Institute of National Importance,[137] one central university[138] and four private universities[139] in Sikkim offering higher education.

Sikkim has a National Institute of Technology, currently operating from a temporary campus in Ravangla, South Sikkim,[140] which is one among the ten newly sanctioned NITs by the Government of India under the 11th Five year Plan, 2009.[141] The NIT Sikkim also has state of art super computing facility named PARAM Kanchenjunga which is said to be fastest among all 31 NITs.[142] Sikkim University is the only central university in Sikkim. The public-private funded institution is the Sikkim Manipal University of Technological Sciences, which offers higher education in engineering, medicine and management. It also runs a host of distance education programs in diverse fields.[143]

There are two state-run polytechnic schools, the Advanced Technical Training Centre (ATTC) and the Centre for Computers and Communication Technology (CCCT), which offer diploma courses in various branches of engineering. ATTC is situated at Bardang, Singtam, and CCCT at Chisopani, Namchi. Sikkim University began operating in 2008 at Yangang, which is situated about 28 kilometres (17 mi) from Singtam.[144] Many students, however, migrate to Siliguri, Kolkata, Bangalore and other Indian cities for their higher education.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "2011 Census reference tables – total population". Government of India. 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- 1 2 "1977 Sikkim government gazette" (PDF). sikkim.gov.in. Governor of Sikkim. p. 188. Archived from the original (pdf) on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- 1 2 "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India" (PDF). 16 July 2014. p. 109. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ↑ Dhar, T. N.; S. P. Gupta (1999). Tourism in Indian Himalaya. Lucknow: Indian Institute of Public Administration. p. 192. OCLC 42717797.

- ↑ "States and Union Territories Symbols". knowindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ↑ "Flora and Fauna". sikkimtourism.gov.in. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ↑ O'Neill, Alexander (2017-03-29). "Sikkim claims India's first mixed-criteria UNESCO World Heritage Site" (PDF). Current Science. 112 (5): 893–994. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ "Why is Sikkim's merger with India being questioned by China?".

- ↑ Lepcha has been an official language since 1977, Limbu since 1981, Tamang since 1995 and Sunwar since 1996.

- 1 2 3 "State-Wise GDP". Unidow.com. 2014. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ Indian Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- 1 2 Paull, John (2017) "Four New Strategies to Grow the Organic Agriculture Sector", Agrofor International Journal, 2(3):61-70.

- 1 2 "Sikkim becomes India's first organic state". Daily News and Analysis. 16 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Sikkim becomes India's first organic state". The Hindu. 14 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Organic show awaits Modi in Sikkim". Telegraph India. 17 January 2016.

- ↑ "Ban on styrofoam products and on use of mineral water bottles in government functions and meetings in Sikkim". Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ↑ "How Sikkim became the cleanest state in India". Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ↑ Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia By James Minahan, 2012

- ↑ Bell, Charles Alfred (1987). Portrait of a Dalai Lama: the life and times of the great thirteenth. Wisdom Publications. p. 25. ISBN 0-86171-055-X.

- 1 2 "Welcome to Sikkim – General Information". Sikkim Tourism, Government of Sikkim. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- ↑ Datta, Amaresh (2006) [1988]. Encyclopaedia of Indian literature vol. 2. Sahitya Akademi. p. 1739. ISBN 81-260-1194-7.

- ↑ "Lepchas and their Tradition". Sikkim.nic.in. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ Skoda, Uwe (2014). Navigating Social Exclusion and Inclusion in Contemporary India and Beyond: Structures, Agents, Practices (Anthem South Asian Studies). Anthem Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-1783083404.

- ↑ "History of Guru Rinpoche". Sikkim Ecclesiastical Affairs Department. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ↑ Central Asia. Area Study Centre (Central Asia), University of Peshawar. v. 41, no. 2. 2005. pp. 50–53.

- ↑ Singh, O. P. (1985). Strategic Sikkim. Stosius/Advent Books. p. 42. ISBN 0-86590-802-8.

- ↑ Singh, O. P. p. 43

- ↑ Sir Clements Robert Markham (1876). Narratives of the Mission of George Bogle to Tibet and of the Journey of Thomas Manning to Lhasa. Via Google Books. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Jha, Pranab Kumar (1985). History of Sikkim, 1817–1904: Analysis of British Policy and Activities. O.P.S. Publishers. p. 11. ASIN B001OQE7EY.

- ↑ "Sikkim and Tibet". Blackwood's Edinburgh magazine. William Blackwood. 147: 658. May 1890.

- 1 2 "History of Sikkim". Government of Sikkim. 29 August 2002. Archived from the original on 30 October 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ↑ Rose, Leo E. (Spring 1969), "India and Sikkim: Redefining the Relationship", Pacific Affairs, 42 (1): 32–46, JSTOR 2754861

- ↑ Rose, Modernizing a Traditional Administrative System 1978, p. 205.

- 1 2 Sethi, Sunil (30 April 1978). "Treaties: Annexation of Sikkim". intoday.in. Living Media India Limited. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ Bell, Charles (1992). Tibet: Past and Present. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 170–174. ISBN 81-208-1048-1.

- ↑ Duff, Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom 2015, p. 41.

- ↑ Duff, Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom 2015, p. 45.

- ↑ Duff, Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom 2015, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Levi, Werner (December 1959), "Bhutan and Sikkim: Two Buffer States", The World Today, 15 (2): 492–500, JSTOR 40393115

- 1 2 du Plessix Gray, Francine (8 March 1981). "The Fairy Tale That Turned Nightmare?". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 3 July 2017; and page 2

- ↑ G. T. (1 March 1975), "Trouble in Sikkim", Index on Censorship, Routledge, doi:10.1080/03064227508532403

- ↑ "About Sikkim". Official website of the Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ↑ "Constitution has been amended 94 times". Times of India. 15 May 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ↑ "India and China agree over Tibet". BBC News. 24 June 2003. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ↑ "Nehru accepted Tibet as a part of China: Rajnath". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ↑ Baruah, Amit (12 April 2005). "China backs India's bid for U.N. Council seat". The Hindu. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- 1 2 "Historic India-China link opens". BBC. 6 July 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ↑ "Himalayan quake toll climbs to 116, 40 stranded foreign tourists rescued". DNA. 21 September 2011.

- ↑ "Earthquake toll over 80; India 68; as rescue teams reach quake epicentre". NDTV. 20 September 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ↑ Madge, Tim (1995). Last Hero: Bill Tilman, a Biography of the Explorer. Mountaineers Books. p. 93. ISBN 0-89886-452-6.

- ↑ "Rivers in Sikkim". Sikkim.nic.in. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ↑ "First commission on study of glaciers launched by Sikkim". dstsikkim.gov.in. 18 January 2008. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ↑ Kapadia, Harish (2001). "Appendix". Across peaks & passes in Darjeeling & Sikkim. Indus Publishing. p. 154. ISBN 81-7387-126-4.

- 1 2 Choudhury 2006, p. 11.

- ↑ Hooker, Joseph Dalton (1855). Himalayan Journals: Notes of a Naturalist. II. London: John Murray. p. 125.

- ↑ Geologic map of Sikkim

- ↑ Bhattacharya, B. (1997). Sikkim: Land and People. Omsons Publications. pp. 7–10. ISBN 81-7117-153-2.

- ↑ "Terrain Analysis and Spatial Assessment of Landslide Hazards in Parts of Sikkim". Journal of the Geological Society of India v. 47. 1996. p. 491.

- ↑ Hooker, Joseph Dalton (1854). Himalayan Journals: Notes of a Naturalist (version 2 ed.). John Murray. p. 396.

- ↑ Choudhury 2006, p. 13.

- ↑ Hooker p. 409

- ↑ "Judge strengths in High Courts increased". Ministry of Law & Justice. 30 October 2003. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- 1 2 "30 Years of Statehood In a Nutshell". Department of Information and Public Relations, Government of Sikkim. 24 November 2005. Archived from the original on 14 July 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ↑ "SDF wins all seats in Sikkim Assembly". The Hindu. 17 May 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ↑ "Shriniwas Patil named new Sikkim governor". Times of India. 4 July 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ Mathew, K. M. (ed.). "India". Manorama Yearbook 2009. Malayala Manorama. p. 660. ISBN 81-89004-12-3.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sikkim at a glance". Department of Information and Public Relations, Government of Sikkim. 29 September 2005. Archived from the original on 31 October 2005. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ↑ "Information of Foreign Tourist Interest". Sikkim.nic.in. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ "State Animals, Birds, Trees and Flower".

- 1 2 O'Neill, Alexander; et al. (2017-03-29). "Integrating ethnobiological knowledge into biodiversity conservation in the Eastern Himalayas". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 13 (21). doi:10.1186/s13002-017-0148-9. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ "Forests in Sikkim". Forest Department, Government of Sikkim. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ↑ "State Animals, Birds, Trees and Flowers of India". Panna Tiger Reserve. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ Wilson DE, Mittermeier RA (eds) (2009) Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 1. Carnivores. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona

- ↑ Sanderson, J.; Khan, J.; Grassman, L. & Mallon, D.P. (2008). "Neofelis nebulosa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ↑ Shrestha, Tej Kumar (1997). Mammals of Nepal. pp. 350–371. ISBN 0-9524390-6-9.

- ↑ Crossette, Barbara (1996). So Close to Heaven: The Vanishing Buddhist Kingdoms of the Himalayas. Vintage Books. p. 123. ISBN 0-679-74363-4.

- ↑ Evans 1932, p. 23.

- ↑ Haribal 2003, p. 9.

- ↑ Dutt, Ashok K.; Baleshwar Thakur (2007). City, Society and Planning: Society. Concept Publishing. p. 501. ISBN 81-8069-460-7.

- ↑ Bareh 2001, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ India: A Reference Annual. New Delhi: Research and Reference Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. 2002. p. 747.

- ↑ Mishra, R. K. (2005). State level public enterprises in Sikkim: policy and planning. Concept Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 81-8069-396-1.

- ↑ "Indian states GDP database" (PDF). NIC.in. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- 1 2 Dasgupta, Abhijit (May 2009). "Forever and ever and ever". India Today. 34 (22): 35. RNI:28587/75.

- ↑ Patil, Ajit (28 May 2009). "Casinos in India". India Bet. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ↑ Sanjay, Roy (27 October 2009). "Indian online gambling market set to open up". India Bet. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

- ↑ Bakshi-Dighe, Arundhati (23 March 2003). "Online lottery: A jackpot for all". Indian Express. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ↑ "Playwin lottery". Interplay Multimedia Pty. Ltd. 20 August 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ↑ "Nathu-la trade gets wider". Telegraph India. 9 May 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ "India China border trade at Nathu La closed for this year". India TV News. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ↑ "Sikkim's first airport to be ready by 2014". Zee News. 12 September 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ "First commercial flight lands at Pakyong". The Economic Times. Press Trust of India. 4 October 2018.

- ↑ "Sikkim's Greenfield Airport". Punj Lloyd Group. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sikkim's New Airport" (PDF) Archived 14 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Maccaferri Environmental Solutions Pvt. Ltd., India. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ "Patel word on speedy airport completion—Sikkim hopes for spurt in tourist inflow". The Telegraph. Kolkata. 2 March 2009. Retrieved 14 June 2009.

- ↑ "How to reach Sikkim" .Government of Sikkim. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ Choudhury 2006, pp. 84–87.

- ↑ "How to Reach Sikkim". Maps of India. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ↑ "Finally, Sevoke-Rangpo railway link on track". ConstructionUpdate.com. November 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ↑ "North Bengal-Sikkim Railway Link". Railway Technology. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ↑ "Inspection survey for Sikkim rail link" Archived 31 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine.. The Hindu. 25 January 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ↑ "Train to Sikkim poses jumbo threat". Times of India. 6 February 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ↑ Gurung, Bijoy (9 December 2010). "Sikkim tour dreams ride on rail plan". Telegraph India. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ↑ Choudhury 2006, p. 91.

- ↑ Choudhury 2006, p. 88.

- ↑ Choudhury 2006, p. 87.

- ↑ "Sikkim becomes first state to achieve 100 per cent sanitation". Infochange India. 9 December 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ↑ "NIRMAL GRAM PURASKAR 2011" Archived 14 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine.. India Sanitation Portal. 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ↑ "Census Population" (PDF). Census of India. Ministry of Finance India. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ↑ "State-wise: Population, GSDP, Per Capita Income and Growth Rate" (PDF). Punjab State Planning Board. 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ↑ "Distribution of the 22 Scheduled Languages". Census of India. Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2001. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ↑ "Census Reference Tables, A-Series – Total Population". Census of India. Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2001. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ↑ Census 2011 Non scheduled languages

- ↑ Bareh 2001, p. 10.

- ↑ "The Ethnic People of Sikkim". PIB.NIC.in. 5 December 2003. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ Clarence, Maloney (1974). Peoples of South Asia. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 409. ISBN 0-03-084969-1.

- ↑ "Census of India – Religious Composition". Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ Bareh 2001, p. 9.

- ↑ "Points of Ministry". IRFA.org.au. 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ Singh, Kumar Suresh (1992). People of India: Sikkim. Anthropological Survey of India. p. 39. ISBN 81-7046-120-0.

- ↑ Nirmalananda Sengupta (1985). State government and politics: Sikkim. Stosius/Advent Books. p. 140. ISBN 0-86590-694-7.

- ↑ "Census and You – Religion". Census India. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ Plaisier, Heleen (2007). Languages of the Greater Himalayan Region. A Grammar of Lepcha. Languages of the Greater Himalayan region. 5. Brill. pp. 4, 15 (photo). ISBN 9004155252.

- ↑ Choudhury 2006, p. 35.

- ↑ Choudhury 2006, p. 34.

- ↑ Sikkim Research Institute of Tibetology (1995). Bulletin of Tibetology. Namgyal Institute of Tibetology. p. 79.

- ↑ "Culture and Festivals of Sikkim". Department of Information and Public Relations, Government of Sikkim. 29 September 2005. Archived from the original on 14 July 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ↑ Bareh 2001, p. 286.

- ↑ Lama, Mahendra P. (1994). Sikkim: Society, Polity, Economy, Environment. Indus Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 81-7387-013-6.

- ↑ Shangderpa, Pema Leyda (3 September 2002). "Sleepy capital comes alive to beats of GenX". The Telegraph. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- ↑ Shrivastava, Alok K. (2002). "Sikkimese cuisine". Surajkund, the Sikkim story. New Delhi: South Asia Foundation. p. 49. ISBN 81-88287-01-6.

- ↑ Nagarajan, Rema (25 July 2007). "India gets its high from whisky". Times of India. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ↑ "Newspapers and Journalists in Sikkim". IT Department, Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ↑ "Publication Place Wise-Registration". Registrar of Newspapers for India. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2009. If one types Sikkim in the input box and submits, the list is displayed.

- ↑ "State of Literacy" (PDF). Census India. Census of India. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ Balmiki Prasad Singh Governor of Sikkim (26 February 2010). "In the process of Constitutional democracy, Sikkim has not lagged behind-Governor" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ "Institutes of National Importance". www.ugc.ac.in. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- ↑ "Central University". www.ugc.ac.in. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- ↑ "Private Universities in Sikkim". www.ugc.ac.in. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- ↑ "NIT Sikkim". nitsikkim.ac.in. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- ↑ "Eleventh Five Year Plan 2007-2012" (PDF). Planning_Prelims: 134.

- ↑ "Hon'ble Governor of Sikkim inaugurated "PARAM Kanchenjunga" at NIT Sikkim". C-DAC.

- ↑ Sailesh (26 June 2010). "Distance Education". Sikkim Manipal University. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ↑ Chettri, Vivek (4 February 2008). "Do-it-yourself mantra for varsity". The Telegraph. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

Further reading and bibliography

- Bareh, Hamlet (2001). "Introduction". Encyclopaedia of North-East India: Sikkim. Mittal Publications. ISBN 81-7099-794-1. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- Choudhury, Maitreyee (2006). Sikkim: Geographical Perspectives. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. ISBN 81-8324-158-1.

- Duff, Andrew (2015), Sikkim: Requiem for a Himalayan Kingdom, Birlinn, ISBN 978-0-85790-245-0

- Evans, W. H. (1932). The Identification of Indian Butterflies (2nd ed.). Mumbai, India: Bombay Natural History Society. ASIN B00086SOSG.

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2011). 'The Tea Horse Road from Lhasa to Sikkim'. China's Ancient Tea Horse Road. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B005DQV7Q2.

- Haribal, Meena (2003) [1994]. Butterflies of Sikkim Himalaya and their Natural History. Sikkim Nature Conservation Foundation. Natraj Publishers. ISBN 81-85019-11-8.

- Rose, Leo E. (1978), "Modernizing a Traditional Administrative System: Sikkim 1890–1973", in James F. Fisher, Himalayan Anthropology: The Indo-Tibetan Interface, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 205–, ISBN 978-90-279-7700-7

- Strachey, Henry (1854). "Physical Geography of Western Tibet". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society. XXIII: 1–69, plus map. ISBN 978-81-206-1044-6. ISSN 0266-6235.

- Ray, Arundhati; Das, Sujoy (2001). Sikkim: A Traveller's Guide. Orient Blackswan, New Delhi. ISBN 81-7824-008-4.

- Hooker, Joseph Dalton (1854). Himalayan Journals: notes of a naturalist in Bengal, the Sikkim and Nepal Himalayas, the Khasia mountains etc. Ward, Lock, Bowden & Co.

- Holidaying in Sikkim and Bhutan. Nest and Wings. ISBN 81-87592-07-9.

- Sikkim – Land of Mystic and Splendour. Sikkim Tourism.

- Manorama Yearbook 2003. ISBN 81-900461-8-7.

External links

- Government

- General information

- Sikkim Encyclopædia Britannica entry

- Sikkim at Curlie (based on DMOZ)