Pan-Turkism

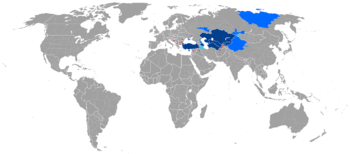

Pan-Turkism is a movement which emerged during the 1880s among Turkic intellectuals of the Russian region of Shirvan (now central Azerbaijan) and the Ottoman Empire (modern day Turkey), with its aim being the cultural and political unification of all Turkic peoples.[1][2][3][4][5] Turanism is a closely related movement but a more general term than Turkism, since Turkism applies only to Turkic peoples. However, researchers and politicians steeped in Turkic ideology have used these terms interchangeably in many sources and works of literature.[6] Although many of the Turkic peoples share historical, cultural and linguistic roots, the rise of a pan-Turkic political movement is a phenomenon of the 19th and 20th centuries.[7] It was in part a response to the development of Pan-Slavism and Pan-Germanism in Europe, and influenced Pan-Iranism in Asia. Ziya Gökalp defined pan-Turkism as a cultural, academic, and philosophical[8] and political[9] concept advocating the unity of Turkic peoples.

Name

In research literature, "pan-Turkism" is used to describe the political, cultural and ethnic unity of all Turkic-speaking people. "Turkism" began to be used with the prefix "pan-" (from the Greek πᾶν, pan = all).[10]

Proponents use the latter as a point of comparison, since "Turkic" is more a linguistic and cultural distinction than a racial or ethnic description. This differentiates it from "Turkish", which is an ethnic term for people primarily residing in Turkey. Pan-Turkic ideas and reunification movements have been popular since the collapse of the Soviet Union in Central Asian and other Turkic countries.

History

In 1804, the Tatar theologian Ghabdennasir Qursawi wrote a treatise calling for the modernization of Islam. Qursawi was a Jadid (from the Arabic jadid, "new"). The Jadids encouraged critical thinking, supporting education and the equality of the sexes, and advocated tolerance for other faiths, Turkic cultural unity, and openness to Europe’s cultural legacy.[11] The Jadid movement was founded in 1843 in Kazan. Its aim was a semi-secular modernization and educational reform, with a national (not religious) identity for the Turks. Before that they were Muslim subjects of the Russian Empire, which maintained this attitude until its end.[12]

After the Wäisi movement, the Jadids advocated national liberation. After 1907, many supporters of Turkic unity immigrated to the Ottoman Empire.

The newspaper Türk in Cairo was published by exiles from the Ottoman Empire after the suspension of the 1876 constitution and the persecution of liberal intellectuals. It was the first publication to use the ethnic designation as its title.[13] Yusuf Akçura published "Three Types of Policy" (Üç tarz-ı siyaset) anonymously in 1904, the earliest manifesto of a pan-Turkic nationalism.[13] Akçura argued that the supra-ethnic union espoused by the Ottomans was unrealistic. The Pan-Islamic model had advantages, but Muslim populations were under colonial rule which would oppose unification. He concluded that an ethnic Turkish nation would require the cultivation of a national identity; a pan-Turkish empire would abandon the Balkans and Eastern Europe in favor of Central Asia. The first publication of "Three Types of Policy" had a negative reaction, but it became more influential by its third publication in 1911 in Istanbul. The Ottoman Empire had lost its African territory to Italy and it would soon lose the Balkans, and pan-Turkish nationalism became a more feasible (and popular) political strategy.

In 1908 the Committee of Union and Progress came to power in Ottoman Turkey, and the empire adopted a nationalistic ideology. This contrasted with its largely Muslim ideology dating back to the 16th century, when the sultan was a caliph of his Muslim lands. Leaders espousing Pan-Turkism fled from Russia to Istanbul, where a strong pan-Turkic movement arose; the Turkish pan-Turkic movement grew into a nationalistic, ethnically oriented replacement of the caliphate with a state. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire with its multi-cultural and multi-ethnic population, influenced by the nationalism of the Young Turks, some tried to replace the empire with a Turkish commonwealth. Leaders like Mustafa Kemal Atatürk acknowledged that such a goal was impossible, replacing pan-Turkic idealism with a nationalism aimed at preserving an Anatolian nucleus.

The Türk Yurdu Dergisi (Journal of the Turkish Homeland) was founded in 1911 by Akçura. This was the most important Turkist publication of the time, "in which, along with other Turkic exiles from Russia, [Akçura] attempted to instill a consciousness about the cultural unity of all Turkic peoples of the world."[13]

A significant early exponent of pan-Turkism was Enver Pasha (1881–1922), the Ottoman Minister of War and acting commander-in-chief during World War I. He later became a leader of the Basmachi movement (1916–1934) against Russian and Soviet rule in Central Asia. During World War II, the Nazis organized a Turkestan legion composed primarily of soldiers who hoped to develop an independent Central Asian state after the war. The German intrigue bore no fruit.[6]

Interest in Pan-Turkism declined, however, with the establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1923 under leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, with Atatürk generally favoring Ziya Gökalp over Enver Pasha.[14][15] Pan-Turkist movements gained some momentum in the 1940s, due to support of Nazi Germany who in the course of the war, sought to leverage Pan-Turkism to undermine Russian influence and in an effort to reach resources of Central Asia.[16] The development of pan-Turkist and anti-Soviet ideology, in some circles, was influenced by Nazi propaganda during this period.[17][18] Some sources claim that Nihal Atsız advocated Nazi doctrines and adopted a Hitler-style haircut and mustache.[19] Alparslan Türkeş, a leading pan-Turkist, took a pro-Hitler position during the war[20] and developed close connections with Nazi leaders in Germany.[21] Several pan-Turkic groups in Europe apparently had ties to Nazi Germany (or its supporters) at the start of the war, if not earlier.[16] The Turco-Tatars in Romania cooperated with the Iron Guard, a Romanian fascist organisation.[16] Although Turkish government archives for the World War II years have not been released, the level of contact can be ascertained from German archives.[16] A ten-year Turco-German treaty of friendship was signed in Ankara on 18 January 1941.[16] Official and semi-official meetings between German ambassador Franz von Papen and other German officials and Turkish officials, including General H. E. Erkilet (of Tatar origin and a frequent contributor to pan-Turkic journals) took place in the second half of 1941 and the early months of 1942.[16] The Turkish officials included General Ali Fuad Erdem and Nuri Pasha, brother of Enver Pasha.[16]

Pan-Turkists were not supported by the government during this time and on 19 May 1944 İsmet İnönü gave a speech condemning Pan-Turkism as "a dangerous and sick demonstration of the latest times" going on to say the Turkish Republic was "facing efforts hostile to the existence of the Republic" and those advocating for these ideas "will bring only trouble and disaster". Nihal Atsiz and other prominent pan-Turkist leaders were tried and sentenced to prison for conspiring against the government. Zeki Velidi Togan was sentenced to 10 years and 4 years of internal exile, Reha Oğuz Türkkan received 2 years and Nihal Atsiz received a four years in prison and 3 year in exile sentence. Others were condemned to more lenient sentences of a few months to a year.[22] But the defendants appealed the convictions and in October 1945, the sentences of all the convicted were abolished by the Military Court of Cassation.[23]

While Erkilet discussed military contingencies, Nuri Pasha told the Germans about his plan to create independent states which would be allies (not satellites) of Turkey. These states would be formed from the Turkic-speaking populations in Crimea, Azerbaijan, Central Asia, northwest Iran, and northern Iraq. Nuri Pasha offered to assist propaganda activities for this cause. However, Turkey also feared for the Turkic minorities in the USSR and told von Papen that it could not join Germany until the USSR was crushed. The Turkish government may have been apprehensive about Soviet might, which kept the country out of the war. On a less-official level, Turkic emigrants from the Soviet Union played a crucial role in negotiations and contacts between Turkey and Germany; among them were prominent pan-Turkic activists like Zeki Velidi Togan, Mammed Amin Rasulzade, Mirza Bala, Ahmet Caferoĝlu, Sayid Shamil and Ayaz İshaki. Several Tatar military units of Turkic speakers in the Turco-Tatar and Caucasian regions who had been prisoners of war joined the war against the USSR, generally fighting as guerrillas in the hope of independence and a pan-Turkic union. The units, which were reinforced, numbered several hundred thousand. Turkey took a cautious approach at the government level, but pan-Turkist groups were exasperated by Turkish inaction and what they saw as the waste of a golden opportunity to reach the goals of pan-Turkism.[16]

After the late-20th-century collapse of the Soviet Union, the Turkic peoples were more independent in business and politics:

The aim of all Turks is to unite with the Turkic borders. History is affording us today the last opportunity. In order for the Islamic world not to be forever fragmented it is necessary that the campaign against Karabagh be not allowed to abate. As a matter of fact drive the point home in Azeri circles that the campaign should be pursued with greater determination and severity.[24]

Pan-Turkic movements and organizations are focusing on the economic integration of the sovereign Turkic states and hope to form an economic and political union similar to the European Union.

Turkey's role

Turkey's efforts have not met the expectations of the Turkic states or the country's pan-Turkist supporters. Modest housing projects promised to the Crimean Tatars have not been completed after many years.

Some language communities have switched to the Latin alphabet, but the official Turkmen, Uzbek and Azerbaijani Latin alphabets are not as compatible with the Turkish alphabet as Turkey had hoped after a Pan-Turkic Alphabet with 35 letters had been agreed upon in the early 1990s prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The Kazakh alphabets already include Latin ones, and Kazakhstan is planned to be fully converted to the Latin alphabet by 2025. Kyrgyzstan has not seriously considered adopting the Latin script, but the idea was entertained by some politicians during the country's first few years of independence, and Roman Kyrgyz alphabets exist.

Criticism

Pan-Turkism is often perceived as a new form of Turkish imperial ambition. Some view the Young Turk leaders who saw pan-Turkist ideology as a way to reclaim the prestige of the Ottoman Empire as racist and chauvinistic.[25][26]

Genocide connections

Some scholars believe that pan-Turkism guided ethnic cleansing, such as the Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian genocides. The agents of the Armenian genocide during the First World War advocated pan-Turkism,[27] and Enver Pasha was a key player in the attempt to remove non-Muslim minorities from the Ottoman Empire in order to build a new pan-Turkic state.[28][29]

Turkic nationalism

Some Turkic nationalists believe that Etruscan—were of Turkic origin.[30][31] Kairat Zakiryanov considers the Japanese and Kazakh gene pools to be identical.[32]

Turkic nationalist writers posit that Eurocentrist colonial regimes falsified and divided Turkic history and Turkic peoples, in justice, must return to Turkic territories.[33] The pseudoscientific Sun Language Theory that all human languages are descendants of a proto-Turkic language was developed by Turkish president Mustafa Kemal Atatürk during the 1930s. In 2012, a Kyrgyz website accused Kazakhs and Uzbeks of appropriating Kyrgyz history.[34]

Armenian history

Clive Foss, professor of ancient history at the University of Massachusetts Boston, has done extensive archeological work in Turkey and he is an expert on ancient Armenian coins. In his article, "The Turkish View of Armenian History: A Vanishing Nation", Foss writes that the Turkish government was "systematically changing the names of villages to make them more Turkish. Any name which does not have a meaning in Turkish, or does not sound Turkish, whatever its origin, is replaced by a banal name assigned by a bureau in Ankara, with no respect for local conditions or traditions".[35] According to Foss, the Turkish government "presented [Armenia] ambiguously, without clear identification of [its] builders, or as examples of the influence of the superiority of Turkish architecture. In all this, a clear line is evident: the Armenian presence is to be consigned, as far as possible, to oblivion".[35]

Foss notes critically that in 1982: The Armenian File in the Light of History, Cemal Anadol writes that the Iranian Scythians and Parthians are Turks. According to 'genius' Anadol, the Armenians welcomed the Turks into the region; their language is a mixture with no roots and their alphabet is mixed, with 11 characters borrowed from the ancient Turkic alphabet. Foss calls this view historical revisionism: "Turkish writings have been tendentious: history has been viewed as performing a useful service, proving or supporting a point of view, and so it is treated as something flexible which can be manipulated at will".[35] He concludes, "The notion, which seems well established in Turkey, that the Armenians were a wandering tribe without a home, who never had a state of their own, is of course entirely without any foundation in fact. The logical consequence of the commonly expressed view of the Armenians is that they have no place in Turkey, and never did. The result would be the same if the viewpoint were expressed first, and the history written to order. In a sense, something like this seems to have happened, for most Turks who grew up under the Republic were educated to believe in the ultimate priority of Turks in all parts of history, and to ignore Armenians all together; they had been clearly consigned to oblivion."[35]

Western Azerbaijan is a term used in Azerbaijan to refer to Armenia. According to the Whole Azerbaijan theory, modern Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh were once inhabited by the Azerbaijanis.[36] Its claims are based on the belief that current Armenia was ruled by Turkic tribes and states from the Late Middle Ages to the Treaty of Turkmenchay which was signed after the Russo-Persian War, 1826-1828. The concept has been sanctioned by the government of Azerbaijan and its current president, Ilham Aliyev, who has said that Armenia is part of ancient Turkic, Azerbaijani land. Turkish and Azerbaijani historians have said that Armenians are alien, not indigenous, in the Caucasus and Anatolia.[37][38][39][40][41]

Russian views

In Tsarist Russian circles, pan-Turkism was considered a political, irredentist and aggressive idea.[42] Turkic peoples in Russia were threatened by Turkish expansion, and I. Gasprinsky and his followers were accused of being Turkish spies. After the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks’ attitude to Türkism did not differ from the Russian Empire’s. At the 10th Congress of Bolshevik Communist Party in 1921, the party "condemned pan-Turkism as a slope to bourgeois-democratic nationalism". The emergence of a pan-Turkism scare in Soviet propaganda made it one of the most frightening political labels in the USSR. The most widespread accusation used in the lethal repression of educated Tatars and other Turkic peoples during the 1930s was that of pan-Turkism.[43]

Russia, China, and Iran say that they perceive pan-Turkism as a new form of Turkish imperial ambition, and some see it as racist. Critics believe that the concept is flawed because of the distinct dialects spoken by the Turkic peoples, which sometimes led to miscommunication. Concerns also exist about religious differences. Although most Turks are Sunnis, there are also predominantly Shi'i peoples (like Azerbaijanis) and predominantly Christian peoples (like Chuvash or Yakuts). According to some, mostly critics from Iran, pan-Turkists are at the forefront of historical revisionism about world history in general and Turkic history in particular.[44]

Pseudoscientific theories

— Orhan Türkdoğan - Professor of Sociology at Gebze Technical University

Pan-Turkism has been characterized by pseudoscientific theories known as Pseudo-Turkology.[46][47] Though dismissed in serious scholarship, scholars promoting such theories, often known as Pseudo-Turkologists,[46] have in recent times emerged among every Turkic nationality.[48][49] A leading light among them is Murad Adzhi, who insists that two hundred thousand years ago, "an advanced people of Turkic blood" were living in the Altai Mountains. These tall and blonde Turks are supposed to have founded the world's first state, Idel-Ural, 35,000 years ago, and to have migrated as far as the Americas.[48] According to theories like the Turkish History Thesis, promoted by pan-Turkic pseudo-scholars, the Turkic peoples are supposed to have migrated from Central Asia to the Middle East in the Neolithic. The Hittites, Sumerians, the Babylonians and ancient Egyptians, are here classified as being of Turkic origin.[47][48][49][50] The Kurgan cultures of the early Bronze Age up to more recent times, are also typically ascribed to Turkic peoples by pan-Turkic pseudoscholars, such as Ismail Miziev.[51] Non-Turkic peoples typically classified as Turkic, Turkish, Proto-Turkish or Turanian, include Huns, Scythians, Sakas, Cimmerians, Medes, Parthians, Pannonian Avars, Caucasian Albania and various ethnic minorities in Turkic countries, such as Kurds.[51][52][53][49][50] Adzhi also considers Alans, Goths, Burgundians, Saxons, Alemanni, Angles, Lombards and many Russians as Turks.[48] Only a few prominent peoples in history, such as Jews, Chinese people, Armenians, Greeks, Persians and Scandinavians are considered non-Turkic by Adzhi.[48] Philologist Mirfatyh Zakiev, former Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Tatar ASSR, has published hundreds of "scientific" works on the subject, suggesting Turkic origins of Sumerian, Greek, Icelandic, Etruscan and Minoan. Zakiev contends that "proto-Turkish is the starting point of the Indo-European languages".[48] Not only peoples and cultures, but also prominent individuals, such as Saint George, Peter the Great, Mikhail Kutuzov and Fyodor Dostoevsky are proclaimed to have been "of Turkic origin".[48] As such the Turkic peoples are supposed to have once been the "benevolent conquerors" of the peoples of most of Eurasia, who thus owe them "a huge cultural debt".[48]

Philip L. Kohl notes that the above-mentioned theories are nothing more than "incredible myths".[51] Nevertheless, the promotion of these theories have "taken on large-scale proportions" in countries such as Turkey and Azerbaijan.[52] Often associated with Greek, Assyrian and Armenian Genocide denial, pan-Turkic pseudoscience has received extensive state and state-backed non-governmental support, and is taught all the way from elementary school to the highest level of universities in such countries.[53] Turkish students are imbued with textbooks making "absurdly inflated" claims that all Eurasian nomads, including the Scythians, and all civilizations on the territory of the Ottoman Empire, such as Sumer, ancient Egypt, ancient Greece and the Byzantine Empire, were of Turkic origin.[54] Konstantin Sheiko and Stephen Brown explains the reemergence of such pseudo-history as a form of national therapy, helping its proponents cope with the failures of the past.[48]

Notable pan-Turkists

- Abulfaz Elchibey, 2nd President of Azerbaijan 1992–93[55][56]

- Ahmet Ağaoğlu

- Alimardan Topchubashov

- Alparslan Türkeş, founder of the Nationalist Movement Party[57][58]

- Askar Akayev

- Enver Pasha

- Fuat Köprülü

- Isa Alptekin

- Ismail Gaspirali

- Mammad Amin Rasulzade

- Mehmet Emin Yurdakul

- Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev

- Mustafa Shokay

- Munis Tekinalp

- Nejdet Sançar

- Nihal Atsız

- Nuri Pasha

- Ömer Seyfettin

- Rıza Nur

- Sadri Maksudi Arsal

- Talaat Pasha

- Yusuf Akçura

- Ziya Gökalp

Pan-Turkist organizations

- Azerbaijan

- Iran

- Southern Azerbaijan National Awakening Movement (SANAM)

- Azerbaijan National Resistance Organization (ANRO)

- Kazakhstan

- National Patriotic Party

- Turkey

- Uzbekistan

Quotations

- Dilde, fikirde, işte birlik ("Unity of language, thought and action")—Ismail Gasprinski, 1839 a Crimean Tatar member of the Turanian Society

- Bu yürüyüş devam ediyor. Türk orduları ata ruhlarının dolaştığı Altay ve Tanrı Dağları eteklerinde geçit resmi yapıncaya kadar devam edecektir. ("This march is going on. It will continue until the Turkic Armies' parade on the foothills of Altai and Tien-Shan mountains where the souls of their ancestors stroll.")—Hüseyin Nihâl Atsız, pan-Turkist author, philosopher and poet

See also

- Turkic peoples

- Idel-Ural

- Altaic languages

- Chauvinism

- Ethnic nationalism

- Nationalist Movement Party

- Hungarian Turanism

- Jobbik

- Historic states represented in Turkish presidential seal

- Pan-nationalism

- Turanid

- Ural–Altaic languages

- Turkic Council

- Turanism

- Turkic languages

- Turco-Mongols

- Tartary

- Division of the Mongol Empire

- Inner Asia

References

- Fishman, Joshua; Garcia, Ofelia (2011). Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-19-539245-6.

It is commonly acknowledged that pan-Turkism, the movement aiming at the political and/or cultural unification of all Turkic peoples, emerged among Turkic intellectuals of Russia as a liberal-cultural movement in the 1880s.

- "Pan-Turkism". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Retrieved 19 Jul 2009.

Political movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which had as its goal the political union of all Turkish-speaking peoples in the Ottoman Empire, Russia, China, Iran, and Afghanistan.

- Landau, Jacob (1995). Pan-Turkism: From Irredentism To Cooperation. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20960-3.

- Jacob M. Landau, "Radical Politics in Modern Turkey", BRILL, 1974.

- Robert F. Melson, "The Armenian Genocide" in Kevin Reilly (Editor), Stephen Kaufman (Editor), Angela Bodino (Editor) "Racism: A Global Reader (Sources and Studies in World History)", M.E. Sharpe (January 2003). pg 278:"Concluding that their liberal experiment had been a failure, CUP leaders turned to Pan-Turkism, a xenophobic and chauvinistic brand of nationalism that sought to create a new empire based on Islam and Turkish ethnicity."

- Iskander Gilyazov, "Пантюрκизм, Пантуранизм и Германия Archived 2006-10-04 at the Wayback Machine", magazine "Татарстан" No 5-6, 1995. (in Russian)

- "Pan-Turkism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Gökalp, Ziya; Devereaux, Robert (1968). The Principles of Turkism. E. J. Brill. p. 125.

Turkism is not a political party but a scientific, philosophic and aesthetic school of thought.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2006). Turkey beyond nationalism: towards post-nationalist identities. I. B. Tauris. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-84511-141-0.

- Mansur Hasanov, Academician of Academy of Sciences of Tatarstan Republic, "Великий реформатор", in magazine "Республика Татарстан" № 96–97 (24393-24394), 17 May 2001. (in Russian)

- Rafael Khakimov, "Taklid and Ijtihad Archived 2007-02-10 at the Wayback Machine", Russia in Global Affairs, Dec. 2003.

- N.N., "Полтора Века Пантюрκизма в Турции", magazine "Панорама". (in Russian)

- Modernism: The Creation of Nation States. p. 218. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- Pan Turkism, Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Eligur, Banu (2010). The Mobilization of Political Islam in Turkey. p. 41.

- Jacob M. Landau. Pan-Turkism: From Irredentism to Cooperation. India University Press, 1995. 2nd Edition. pp 112–114.

- Jacob M. Landau, "Radical Politics in Modern Turkey", BRILL, 1974. pg 194: "In the course of the Second World War, various circles in Turkey absorbed Nazi propaganda; these were pro-German and admired Nazism, which they grasped as a doctrine of warlike dynamism and a source of national inspiration, on which they could base their pan-Turkic and anti-Soviet ideology"

- John M. VanderLippe , "The politics of Turkish democracy", SUNY Press, 2005. "A third group was led by Nihal Atsiz, who favored a Hitler style haircut and mustache, and advocated racist Nazi doctrines"

- John M. VanderLippe, The Politics of Turkish Democracy: Ismet Inonu and the Formation of the Multi-Party System, 1938-1950, (State University of New York Press, 2005), 108;"A third group was led by Nihal Atsiz, who favored a Hitler style haircut and moustache, and advocated Nazi racist doctrines."

- Peter Davies, Derek Lynch, "The Routledge Companion to Fascism and the Far Right", Routledge, 2002. pg 244: "Alparslan Türkeş: Leader of a Turkish neo-fascist movement, Nationalist Action Party(MHP). During the war he took a pro-Hitler position and was imprisoned after a 1960 coup attempt against his country's ruler.

- Berch Berberoglu, " Turkey in crisis: from state capitalism to neocolonialism", Zed, 1982. 2nd edition. pg 125: "Turkes established close ties with Nazi leaders in Germany in 1945 "

- VanderLippe, John M. (2012-02-01). Politics of Turkish Democracy, The: Ismet Inonu and the Formation of the Multi-Party System, 1938-1950. SUNY Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780791483374.

- Landau, Jacob M.; Landau, Gersten Professor of Political Science Jacob M.; Landau, Yaʻaqov M. (1995). Pan-Turkism: From Irredentism to Cooperation. Indiana University Press. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-0-253-32869-4.

- Karabekir, Istiklâl Harbimiz/n.2/, p. 631

- Jacob M. Landau. Pan-Turkism: From Irredentism to Cooperation. India University Press, 1995. 2nd Edition. pg 45: "Pan-Turkism's historic chance arrived shortly before and during First World War, when it was adopted a guiding principle of state policy by an influential group among the Young Turks"

- Robert F. Melson, "The Armenian Genocide" in Kevin Reilly (Editor), Stephen Kaufman (Editor), Angela Bodino (Editor) "Racism: A Global Reader (Sources and Studies in World History)", M.E. Sharpe (January 2003). pg 278: "Concluding that their liberal experiment had been a failure, CUP leaders turned to Pan-Turkism, a xenophobic and chauvinistic brand of nationalism that sought to create a new empire based on Islam and Turkish ethnicity ... It was in this context of revolutionary and ideological transformation and war that the fateful decision to destroy the Armenians was taken."

- The International Association of Genocide Scholars, Affirmation, Armenian Genocide, "That this assembly of the Association of Genocide Scholars in its conference held in Montreal, June 11–3, 1997, reaffirms that the mass murder of Armenians in Turkey in 1915 is a case of genocide which conforms to the statutes of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide. It further condemns the denial of the Armenian Genocide by the Turkish government and its official and unofficial agents and supporters".

- Young Turks and the Armenian Genocide, Armenian National Institute

- Robert Melson, Leo Kuper, "Revolution and genocide: on the origins of the Armenian genocide and the Holocaust", University of Chicago Press, 1996. pg 139: "It was in this context of exclusion and war that CUP made a decision to destroy the Armenians as a viable national community in Turkey and the pan-Turkic empire. Thus a revolutionary transformation of ideology and identity for the majority had dangerous implications for the minority. As will be discussed in Chapter 5, the Turkish nationalists revolution, as initiated by the Young Turks, set the stage for the Genocide of Armenians during the Great war"

- Lynn Meskell, "Archaeology Under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East", Routledge, 1998.

- "Мустафа (Кемаль) Ататюрк Мустафа Ататюрк". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- К.Закирьянов. Я вполне допускаю мысль, что в жилах Обамы течет тюркская кровь (Russian)

- "Доктор истнаук А.Галиев: Покажите мне паспорт Чингисхана, где написано, что он казах. Тогда я вам поверю... - ЦентрАзия". Archived from the original on 2016-03-24. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- "Казахи интересуются нашей историей". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Clive Foss, “The Turkish View of Armenian History: A Vanishing Nation,” in The Armenian Genocide: History, Politics, Ethics, ed. by Richard G. Hovannisian (New York: St. Martins Press, 1992), p. 268.

- "Present-day Armenia located in ancient Azerbaijani lands - Ilham Aliyev". News.Az. October 16, 2010. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015.

- Tofig Kocharli "Armenian Deception"

- Ohannes Geukjian "Ethnicity, Nationalism and Conflict in the South Caucasus: Nagorno-Karabakh and the Legacy of Soviet Nationalities Policy"

- "Nagorno Karabakh: History". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- "Рауф Гусейн-заде: "Мы показали, что армяне на Кавказе - некоренные жители"". Day.Az. 27 December 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- "Professor Firidun Agasyoglu Jalilov "How Hays became Armenians"". Archived from the original on 2015-02-15. Retrieved 2014-11-11.

- Geraci, Robert P. (2001). Window on the East: National and Imperial Identities in Late Tsarist Russia. Cornell University Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-8014-3422-8.

- Mansur Hasanov, Academician of Academy of Sciences of Tatarstan republic, in "People's Political Newspaper" № 96–97 (24393-24394) 17 May 2001 http://www.rt-online.ru/numbers/public/?ID=25970

- Pan-Turanianism Takes Aim at Azerbaijan: A Geopolitical Agenda By: Dr. Kaveh Farrokh

- Gunes, Cengiz; Zeydanlioglu, Welat (2013). The Kurdish Question in Turkey: New Perspectives on Violence, Representation and Reconciliation. Routledge. p. 11. ISBN 1135140634.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frankle, Elanor (1948). Word formation in the Turkic languages. Columbia University Press. p. 2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aktar, A.; Kizilyürek, N; Ozkirimli, U.; K?z?lyürek, Niyazi (2010). Nationalism in the Troubled Triangle: Cyprus, Greece and Turkey. Springer. p. 50. ISBN 0230297323.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheiko, Konstantin; Brown, Stephen (2014). History as Therapy: Alternative History and Nationalist Imaginings in Russia. ibidem Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 3838265653.

According to Adzhi, Huns, Alans, Goths, Burgundians, Saxons, Alemans, Angles, Langobards and many of the Russians were ethnic Turks.161 The list of non-Turks is relatively short and seems to comprise only Jews, Chinese, Armenians, Greeks, Persians, and Scandinavians... Mirfatykh Zakiev, a Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Tatar ASSR and professor of philology who has published hundreds of scientific works, argues that proto-Turkish is the starting point of the Indo-European languages. Zakiev and his colleagues claim to have discovered the Tatar roots of the Sumerian, ancient Greek and Icelandic languages and deciphered Etruscan and Minoan writings.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Khazanov, Anatoly M. (1996). Post-Soviet Eurasia: Anthropological Perspectives on a World in Transition. Department of Anthropology, University of Michigan. p. 84. ISBN 1889480002.

Discredited hypotheses — widespread in the 1920s and 1930s — about the Turkic origin of Sumerians, Scythians, Sakhas, and many other ancient peoples are nowadays popular

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Hunter, Shireen; Thomas, Jeffrey L.; Melikishvili, Alexander (2004). Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security. M.E. Sharpe. p. 159. ISBN 0765612828.

M. Zakiev claims that the Scythians and Sarmatians were all Turkic. He even considers the Sumerians as Turkic

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Kohl, Philip L.; Fawcett, Clare (1995). Nationalism, Politics and the Practice of Archaeology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 143, 154. ISBN 0521558395.

Apparently innocuous were other contradictory and/or incredible myths related by professional archaeologists that claimed that the Scythians were Turkic-speaking

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Simonian, Hovann (2007). The Hemshin: History, Society and Identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey. Routledge. p. 354. ISBN 0230297323.

Thus, ethnic groups or populations of the past (Huns, Scythians, Sakas, Cimmerians, Parthians, Hittites, Avars and others) who have disappeared long ago, as well as non-Turkic ethnic groups living in present-day Turkey, have come to be labeled Turkish, Proto-Turkish or Turanian

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Lornjad, Siavash; Doostzadeh, Ali (2012). On The Modern Politization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi. CCIS. p. 85. ISBN 9993069744.

Claims that many Iranian figures and societies starting from the Medes, Scythians and Parthians were Turks), are still prevalent in countries that adhere to Pan—Turkist nationalism such as Turkey and the republic of Azerbaijan. These falsifications, which are backed by state and state backed non—governmental organizational bodies, range from elementary school all the way to the highest level of universities in these countries.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Boldt, Andreas (2017). Historical Mechanisms: An Experimental Approach to Applying Scientific Theories to the Study of History. Taylor & Francis. p. 107. ISBN 1351816489.

Violent flirtation with PanTuranism had a lasting effect on kemalist Turkey and its historical ideology: Turkish pupils are imbued by history textbooks even today with a dogma of absurdly inflated PanTurkish history—Turkish history comprises all Eurasian nomads, Indo-European (Scythian) and Turk-Mongol, plus their conquests in Persia, India China, all civilizations on the soil of the Ottoman Empire, from Sumer and Ancient Egypt via Greeks, Alexander the Great to Byzantium.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Balci, Bayram (2014). "Between ambition and realism: Turkey's engagement in the South Caucasus". In Agadjanian, Alexander; Jödicke, Ansgar; van der Zweerde, Evert (eds.). Religion, Nation and Democracy in the South Caucasus. Routledge. p. 258.

...the second president of independent Azerbaijan, Abulfaz Elchibey, was a prominent pan-Turkist nationalist...

- Murinson, Alexander (2009). Turkey's Entente with Israel and Azerbaijan: State Identity and Security in the Middle East and Caucasus. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 9781135182441.

Naturally, they were associated with Elchibey's pan-Turkist aspirations...

- Hale, William M. (2000). Turkish Foreign Policy, 1774-2000. Psychology Press. p. 292. ISBN 9780714650715.

Within Turkey, the pan- Turkist movement led by Alparslan Türkeş...

- Larrabee, F. Stephen; Lesser, Ian O. (2003). Turkish Foreign Policy in an Age of Uncertainty. Rand Corporation. p. 123. ISBN 9780833034045.

The late Alparslan Turkes, the former head of the MHP, actively promoted a Pan-Turkic agenda.

Further reading

- Jacob M. Landau. Pan-Turkism: From Irredentism to Cooperation. Hurst, 1995. ISBN 1-85065-269-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pan-Turkism. |