Hungarian Turanism

Hungarian Turanism (Hungarian: Turánizmus / Turanizmus) is a diverse phenomenon that revolves around an identification or association of Hungarian history and people with the histories and peoples of Central Asia, Inner Asia or the Ural region. It includes many different conceptions and served as a guiding principle for many political movements. It was most lively in the second half of the 19th century and in the first half of the 20th century. It is related to the concept of Turanism.

Background

Hungarian nobiliary historical tradition considered the Turkish peoples the closest relatives of Hungarians.[1] This tradition was preserved in medieval chronicles (such as Gesta Hungarorum[2] and Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum,[3] the Chronicon Pictum, and Chronica Hungarorum by Johannes de Thurocz) as early as the 13th century. According to Chronica Hungarorum, the Hungarians are descendants of the Huns, and came from the Asian parts of Scythia, and Turks share this Scythian origin with them. This tradition served as starting point for the scientific research of the ethnogenesis of Hungarian people, which began in the 18th century, in Hungary and abroad. Sándor Kőrösi Csoma (the writer of the first Tibetan-English dictionary) traveled to Asia in the strong belief that he could find the kindred of Magyars in Turkestan, amongst the Uyghurs.[4]

Before the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin, the Hungarians were semi-nomadic[5] and their culture was similar to other steppe peoples. Most scientists presume a Uralic homeland for the ancient Hungarian conquerors (mainly on genealogical linguistic grounds, and on the basis of genetic research carried out on a limited number of ancient skeletons found in graves from the age of the conquest[6]). The proto-Hungarian tribes lived in the Eurasian forest steppe zone,[7] and so these ancient ancestors of Hungarians and their relationship with other equestrian nomadic peoples has been and still is a topic for research.[8]

As a scientific movement, Turanism was concerned with research into Asian cultures in the context of Hungarian history and culture. It was embodied and represented by many scholars who had shared premises (i.e. the Asian origin of the Hungarians, and their kinship with Asian peoples), and who arrived at the same or very similar conclusions. Turanism was a driving force in the development of Hungarian social sciences, especially linguistics, archaeology and Orientalism.

Political Turanism was born in the 19th century, in response to the growing influence of Pan-Germanism and Pan-Slavism, seen by Hungarians as very dangerous to the nation, and the state of Hungary, because the country had large ethnic German and Slavic populations.[1] This political ideology originated in the work of the Finnish nationalist and linguist Matthias Alexander Castrén, who championed the ideology of Pan-Turanism — the belief in the racial unity and future greatness of the Ural-Altaic peoples. He concluded that the Finns originated in Central Asia and far from being a small, isolated people, they were part of a larger community that included such peoples as the Magyars, the Turks, and the Mongols etc.[9] Political Turanism was a romantic nationalist movement, which stressed the importance of common ancestry and cultural affinity between Hungarians and the peoples of the Caucasus and Inner and Central Asia, such as the Turks, Mongols, Parsi etc. It called for closer collaboration and political alliance between them and Hungary, as a means of securing and furthering shared interests and to counter the threats posed by the policies of the great powers of Europe. The idea for a "Turanian brotherhood and collaboration" was borrowed from the Pan-Slavic concept of "Slavic brotherhood and collaboration".[10]

After the First World War, political Turanism played a role in the formation of Hungarian far-right ideologies because of its ethnic nationalist nature.[11][12] It began to carry anti-Jewish sentiments and tried to show the "existence and superiority of a unified Hungarian race".[12] Nonetheless, Andrew C. Janos asserts that Turanism's role in the interwar development of far-right ideologies was negligible.[13]

In the communist era after the Second World War, Turanism was portrayed and vilified as an exclusively fascist ideology.[14] Since the fall of communism in 1989 there has been a renewal of interest in Turanism.

Its roots, origins, and development

The beginnings

It is a well-known fact that the marked interest in the genetic classification of languages prevailing in the last century and at the beginning of the present one has its roots in European nationalisms. The exact knowledge of dialects and languages was supposed to strengthen the national individuality and to align nations in ‘natural’ alliances.[15]

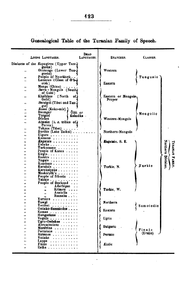

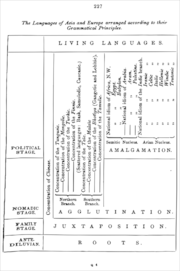

Friedrich Max Müller, the German Orientalist and philologist, published and proposed a new grouping of the non-Aryan and non-Semitic Asian languages in 1855. In his work "The languages of the seat of war in the East. With a survey of the three families of language, Semitic, Arian, and Turanian." he called these languages "Turanian". Müller divided this group into two subgroups, the Southern Division, and the Northern Division. Hungarian language was classed by him as a member of this Northern Division, in the Finnic Class, in the Ugric Branch, with the Voguls and Ugro-Ostiakes as closest relatives.[16] (In the long run, his evolutionist theory about languages' structural development, tying growing grammatical refinement to socio-economic development, and grouping languages into 'antediluvian', 'familial', 'nomadic', and 'political' developmental stages [17] proved unsound, but his Northern Division was renamed and re-classed as the Ural-Altaic languages.) His theory was well known and widely discussed in international scientific circles, and was known to Hungarian scientists as well. He was invited to Budapest, the Hungarian capital, by Ármin Vámbéry, the Orientalist and Turkologist, in 1874, and become an associate member of the Hungarian Aceademy of Sciences. His public lectures received wide attention, and his terms (originally borrowed by him from Persian texts like the Shahnameh which used the term "Turan" to denote the territories of Turkestan, north of Amu Darya river, inhabited by nomadic warriors) "Turan" and "Turanian" become denizens in Hungarian language as "Turán" and "turáni". The meaning of these terms was never defined officially. Vámbéry himself used "Turan" to denote the areas of Eastern Balkan, Central and Inner Asia inhabited by Turkic peoples, and used "Turanian" to denote those Turkic peoples and languages (and he meant the Finno-Ugric peoples and languages as the members of this group), which lived in or originated from this "Turan" area. Hungarian scientists shared his definition. But in common parlance these terms were used in many (and often different) meanings and senses.

Hungarians have had a thousand year old, and still living tradition about the Asian origins of Magyars. This tradition was preserved in medieval chronicles (such as Gesta Hungarorum[2] and Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum[3]) as early as the 13th century. This tradition served as starting point for the scientific research of the ethnogenesis of Hungarian people, which began in the 18th century, in Hungary and abroad. Sándor Kőrösi Csoma (the writer of the first Tibetan-English dictionary) traveled to Asia in the strong belief that he could find the kindred of Magyars in Turkestan, amongst the Uyghurs.[4][18]

"...when Kőrösi set off for the search of the ancient homeland of Magyars and the 'left behind Magyars', he considered that he might find those somewhere in Central Asia, respectively amongst the Uighurs..."[4]

Vámbéry Ármin had the same motivation for his travels to Asia and the Ottoman Empire.

"...from this came my hope, that with the help of comparative linguistics I could find a ray of light in Central Asia, which dispels the gloom over the dark corners of Hungarian prehistory..."

"...következett tehát ebből az a reménységem, hogy Középázsiában az összehasonlító nyelvtudomány segítségével világosságot vető sugarat lelhetek, mely eloszlatja a homályt a magyar őstörténelem sötét tájairól...." in: Vámbéry Ármin: Küzdelmeim. Ch.IV. p. 62.[19]

The linguistic theories of the Dutch philosopher Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn and the German thinker Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz gave the real basis of the modern scientific research of the origin of the Hungarian language and people. Boxhorn conjectured that the European and Indo-Iranian languages were all derived from a shared ancestor language, and he named this ancestor language "Scythian", after the equestrian, nomadic warriors of the Asian steppes. But linguists theorizing about ancestor languages had to deal with the common belief of the era, that, according to the Bible, Hebrew was the original language of all humans. Leibniz published material countering the Biblical theory, and supported Boxhorn's notion of a Scythian ancestor language.

"Information about hither-to unknown peoples and languages of Asia and the Americas came into the hands of scholars such as Gottfried Leibniz, who recognized that there was no better method “for specifying the relationship and origin of the various peoples of the earth, than the comparison of their languages”. In order to classify as many languages as possible in genealogical groupings, Leibniz proposed that similar materials be collected from each newly described language. To this end he asked that explorers either obtain translations of well-known Christian prayers such as the Pater Noster, or, better yet, “words for common things” (vocabula rerum vulgarium), a sample list of which he appended to a letter to the Turkologist D. Podesta (Leibniz 1768/1989b).The word list included numerals, kinship terms, body parts, necessitates (food, drink, weapons,domestic animals), naturalia (God, celestial and weather phenomena, topographic features, wild animals) and a dozen verbs (eat, drink, speak, see …). Leibniz took a particular interest in the expansion of the Russian Empire southward and eastward, and lists based on his model were taken on expeditions sent by the tsars to study the territories recently brought under their control, as well as the peoples living on these and on nearby lands." Kevin Tuite: The rise and fall and revival of the Ibero-Caucasian hypothesis. 2008. in: Historiographia Linguistica, 35 #1; p. 23-82.

Leibniz recognized that the Semitic languages such as Hebrew and Arabic, and some European languages like Sami, Finnish, and Hungarian did not belong to the same language family as most of the languages of Europe. He recognized the connection between the Finnish languages and Hungarian. He placed the original homeland of the Hungarians to the Volga-Caspian Sea region.

These theories had a great impact on the research of the origins of the Hungarian language and the ethnogenesis of Hungarian nation. Both of the two main views/theories about the origin of the Hungarian people and language, the one about the Turkic origin, and the other about the Finno-Ugric origin had their scientific roots in them.

In fact, the Turkic theory matched the tradition (the Gestas) and historical sources (like the works of Constantine VII and Leo VI the Wise) better, but the accounts and works of travelers like Swedish Philip Johan von Strahlenberg (published in his work:" An historico-geographical description of the north and east parts of Europe and Asia ") turned the attention to the "Finnish-Hungarian connection".[20]

Johann Eberhard Fischer (1697-1771) was a German historian and language researcher, who participated in the Great Northern Expedition of 1733-1743. In his work “Qvaestiones Petropolitanae, De origine Ungrorum”, published in 1770, he put Hungarian into a group of kindred peoples and languages which he called 'Scythian'. He considered the Ugric peoples (he called them ‘Jugors’, these are the Khanty and Mansi) the closest relatives of Hungarians, actually as ‘Magyars left behind’, and originated them from the Uyghurs, who live on the western frontiers of China.

The followers of the "Turkist" and "Ugrist" theories lived together peacefully, and the theories were refined as science developed. (In fact the two theories converged, as linguists, like Rasmus Christian Rask, Wilhelm Schott (1802-1889) and Matthias Castrén recognized the similarities and connection between Finn-Ugric and Altaic languages. The German linguist and Orientalist Schott was a proponent of Finn-Turk-Hungarian kinship, and considered the Hungarians a mixture of Turks and Hyperboreans / i.e. Saami, Samoyed etc. /.[21]) The discourse remained fully scientific up until the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 and the 1848-49 War of Independence but after the bitter experiences of the war and the defeat everything got political overtones.

"... the Sun went down into a sea of blood. The night of immeasurable grief fell on Hungary; her noblest powers were broken. Even the gates of scientific institutions became closed..."

"...a Nap vértengerbe áldozott le. Magyarországra a mérhetetlen gyásznak éjszakája borult; legnemesebb erői törve voltak. Még a tudományos intézetek kapui is bezárultak..." in: Herman Ottó: Petényi J. S. a magyar tudományos madártan megalapítója. p. 39.[22]

The role of the Habsburgs

Hungary's constitution and her territorial integrity were abolished, and her territory was partitioned into crown lands. This signalled the start of a long era of absolutist rule. The Habsburgs introduced dictatorial rule, and every aspect of Hungarian life was put under close scrutiny and governmental control. Press and theatrical/public performances were censored.[23][24]

German became the official language of public administration. The edict issued on 1849.X.9. (Grundsätze für die provisorische Organisation des Unterrichtswesens in dem Kronlande Ungarn), placed education under state control, the curriculum was prescribed and controlled by the state, the education of national history was confined, and history was educated from a Habsburg viewpoint.[25] Even the bastion of Hungarian culture, the Academy was kept under control: the institution was staffed with foreigners, mostly Germans and ethnic Germans, and the institution was practically defunct until the end of 1858.[26][27][28] Hungarians responded with passive resistance. Questions of nation, language, national origin became politically sensitive matters. Anti-Habsburg and anti-German sentiments were strong. A large number of freedom fighters took refuge in the Ottoman Empire. This resulted in renewed cultural exchange, and mutual sympathy. Turks were seen by many as good allies of the Hungarian cause. Such was the atmosphere, when Vámbéry traveled to Constantinople in 1857 for the first time.[18]

"It should happen and it will happen - I encouraged myself with this, and did not hurt me other problems, just this one: how could I get a passport from the strict and suspicious Austrian authorities, and exactly to Turkey, where the Hungarian emigration resided, and, as was believed in Vienna, made rebellious plans tirelessly."

"Mennie kell és menni fog, - ezzel biztattam magam és nem bántott más gond, csak az az egy: hogy mi úton-módon kaphatok útlevelet a szigorú és gyanakvó osztrák hatóságtól; hozzá még épen Törökországba, hol akkor a magyar emigráczió tartotta székét és, mint Bécsben hitték, pártütő terveket sző fáradhatatlanúl." in: Vámbéry Ármin: Küzdelmeim. Ch. IV. p. 42.[19]

And this atmosphere granted public interest for the then new theory of Max Müller. The Habsburg government saw this "Turkism" as dangerous to the empire, but had no means to suppress it. (The Habsburg Empire lost large territories in the early 19th century /Flanders and Luxembourg/, and lost most of its Italian holdings a little later, so many members of the Austrian political elite (Franz Joseph I of Austria himself, Archduke Albrecht, Duke of Teschen, major general Ferdinand Franz Xaver Johann Freiherr Mayerhofer von Grünbühel for example)[29]) dreamed about Eastern land grabs.[30][31])

As a consequence of the Franco-Austrian War and the Austro-Prussian War, the Habsburg Empire was on the verge of collapse in 1866, because these misfortunate military endeavours resulted in increased state spending, speeding inflation, towering state debts and financial crisis.[32]

The Habsburgs were forced to reconcile with Hungary, to save their empire and dynasty. The Habsburgs and part of the Hungarian political elite arranged the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. The Compromise was arranged and legitimated by a very small part of the Hungarian society (suffrage was very limited: less than 8 percent of the population had voting rights), and was seen by a very large part of the population as betrayal of the Hungarian cause and the heritage of the 1848-49 War of Independence.[33] This caused deep and lasting cracks in Hungarian society. Academic science remained under state scrutiny and pressure, and press remained under (albeit more permissive) censorship. Matters of nation, language, national origin remained politically sensitive themes, and Turkism remained popular.

"However, to get the Compromise accepted within the society posed serious difficulties. Many counties (for example Heves, Pest, Szatmár) rejected the Compromise and stood up for Kossuth, the opposition organized a network of Democratic circles, on the Great Hungarian Plain anti-government and anti-Compromise demonstrations of several thousand men took place, etc. The government, suspending its liberal principles, decided to take firm counter moves: imprisoned László Böszörményi who published the Kossuth letters, banned the Democratic circles, sent a royal commissioner to the most resistant Heves County. The stabilization of the system and the admittance of new political institutions, however, still dragged on for years."

"Viszont a kiegyezés elfogadtatása a társadalommal, komoly nehézségekbe ütközött. Több megye (például Heves, Pest, Szatmár) elutasította a kiegyezést és kiállt Kossuth mellett, az ellenzék megszervezte a demokrata körök hálózatát, az Alföldön többezres kormány- és kiegyezés-ellenes népgyűlésekre került sor stb. A kormány, felfüggesztve liberális elveit, határozott ellenlépésekre szánta el magát: bebörtönözte a Kossuth leveleit közlő Böszörményi Lászlót, betiltotta a demokrata köröket, a leginkább ellenálló Heves megyébe pedig királyi biztost küldött. A rendszer stabilizálása és az új politikai intézmények elfogadása azonban még így is évekig elhúzódott." in: Cieger András: Kormány a mérlegen - a múlt században.[34]

Ármin Vámbéry's work

Vámbéry started his second journey into Asia in July 1861 with the approval and monetary help of the Akadémia and its president, Emil Dessewffy. After a long and perilous journey he arrived at Pest in May 1864. He went to London to arrange the English language publication of his book about the travels. "Travels in Central Asia" and its Hungarian counterpart "Közép-ázsiai utazás" were published in 1865. Thanks to his travels Vámbéry became an internationally renowned writer and celebrity. He became acquainted with members of British social elite. The Ambassador of Austria in London gave him a letter of recommendation to the Emperor, who received him in an audience and rewarded Vámbéry's international success by granting him professorship in the Royal University of Pest.[19]

Vámbéry published his "Vámbéry Ármin vázlatai Közép-Ázsiából. Ujabb adalékok az oxusmelléki országok népismereti, társadalmi és politikai viszonyaihoz." in 1868. Perhaps this was the first instance of the use of the word "turáni" in a Hungarian language scientific text.

At the beginning of Hungarian Turanism, some of its notable promoters and researchers, like Ármin Vámbéry, Vilmos Hevesy,[35][36] (Also known as Wilhelm von Hevesy(1877-1945) He was the older brother of György Hevesy, and an electrical engineer by profession, although he was kind of a Finno-Ugrist publishing books and other writings about the Finno-Ugric-Munda kinship, like "Munda-Magyar-Maori, an Indian link between the antipodes new tracks of Hungarian origins" and "Finnisch-Ugrisches aus Indien" in the 1920s and 30's.[37]) and Ignác Goldziher[38][39] were Jewish or of Jewish descent (Vámbéry was neither proud nor ashamed of his Jewish ancestry, he became a member of the Reformed Church, and considered himself Hungarian).

Vámbéry was a key figure in the development of Turanism, and in the development of the "scientific consciousness" of the general public. He was a talented writer: he presented serious scientific matters in an interesting, readable manner. His enjoyable books and other writings, presenting customs, traditions and culture of far-flung peoples and faraway places were key in raising wide public interest in ethnography, ethnology and history. In fact, the power of his books, coupled with the widespread disillusionment about the political elite turned public attention to the lower classes and peasantry, as better heirs and keepers of real Hungarian legacy.(The neologists of the first half of the 19th century had turned towards folklore, myths, ballads and tales in their search of a new national literary style, but had not had interest in other aspects of rural peasant life.)

Vámbéry's later work, entitled "Magyar és török-tatár szóegyezések."[40] and published in 1869-70, was the casus belli of the "Ugor-török háború" ("Ugric-Turk War"), which started as a scientific dispute, but quickly turned into a long-lasting (it raged for two decades) bitter feud. In this work Vámbéry tried to prove with the help of word comparisons, that as a result of intermingling of the early Hungarians with Turkic peoples, the Hungarian language got a distinct dual (Ugric AND Turkic) character, albeit it is basically Ugric in origin, so he presented a variant of linguistic contact theory.

"...the Hungarian language is Ugric in its origin, but because the nations later contact and historical transformation it is equally Ugric and Turkic in character..."

"...a magyar nyelv eredetében ugor, de a nemzet későbbi érintkezése és történeti átalakulásánál fogva egyformán ugor és török jellemű..." in: Vámbéry Ármin: Magyar és török-tatár szóegyezések. p. 120.

The "Ugric-Turkic War"

"The fight, which my fanatical opponents, regrettably, brought over also to the field of personal remarks, lasted quite a long time, but the old Latin proverb was proven once again: Philologi certant, tamen sub judice lis."

"A küzdelem, melyet fanatikus ellenfeleim, sajnos, átvittek a személyeskedés terére is, eltartott jó sokáig, de ezúttal is bevált a régi diák közmondás: Philologi certant, tamen sub judice lis." in: Vámbéry Ármin: Küzdelmeim. Ch. IX. p. 130.[19]

Vámbéry's work was criticized by Finno-Ugrist József Budenz in "Jelentés Vámbéry Ármin magyar-török szóegyezéséről.", published in 1871. Budenz criticised Vámbéry and his work in an aggressive, derogatory style, and questioned Vámbéry's (scientific) honesty and credibility. (Budenz's work was investigated and analysed by a group of modern linguists, and they found it neither as scientific nor as conclusive in the question of the affiliation of Hungarian language, as the author stated.)[41]

The historian Henrik Marczali, linguist Károly Pozder, linguist József Thúry, anthropologist Aurél Török, and others supported Vámbéry.[1][42][43][44]

The Finn-Ugrist Pál Hunfalvy widened the front of the "Ugric-Turk War" with his book "Magyarország ethnographiája.",[45] published in 1876. In this book he stresses the very strong connection between language and nation (p. 48.), tries to prove that the Huns were Finn-Ugric (p. 122.), questions the credibility and origin of the Gestas (p. 295.), concludes that the Huns, Bulgars and Avars were Ugric (p. 393.), mentions, that the Jews are more prolific than other peoples, so the quickly growing number of them presents a real menace for the nation (p. 420.), and stresses what an important and eminent role the Germans played in the development of Hungarian culture and economy (p. 424.).

In his work titled "Vámbéry Ármin: A magyarok eredete. Ethnologiai tanulmány.",[46] and published in 1882, Vámbéry went a step further, and presented a newer version of his theory, in which he claimed that Hungarian nation and language are basically Turkic in origin, and the Finn-Ugric element in them is a result of later contact and intermingling.

"...I see a compound people in Hungarians, in which not the Finn-Ugric, but the Turkic-Tatar component gives the true core..."

"...a magyarban vegyülék népet látok, a melyben nem finn-ugor, hanem török-tatár elem képezi a tulajdonképeni magvat..." in: Vámbéry Ármin: A magyarok eredete. Ethnologiai tanulmány. Preface. p. VI.

Vámbéry's work was criticized heavily by his Finno-Ugrist opponents. This critique gave rise to the ever-circling myth of the "fish-smelling kinship" and its variants. No one of the authors has ever given the written source/base of this accusation against the Turanist scientists. In fact, Turanist scientists did not write such things about the Finn-Ugric peoples, and Vámbéry and his followers mentioned these kin of Hungarians with due respect. In reality it was coined by the Finno-Ugrist Ferdinánd Barna, in his work "Vámbéry Ármin A magyarok eredete czímű műve néhány főbb állításának bírálata." (“Critique of some main statements of Ármin Vámbéry’s work, titled ‘The origin of Hungarians’.”) published in 1884. In this work Barna called the Finno-Ugric peoples "a petty, fish fat eating people spending their woeful lives with fish- and easel-catching", and tried to give this colorful description of his into Vámbéry’s mouth.[47]

Vámbéry held to his scientific theory about the mixed origin of Hungarian language and people till his death. He considered Hungarian a contact language, more precisely a mixed language, having not just one but two (Finno-Ugric AND Turkic) genetic ancestors. His strongest evidences were the large corpus of ancient Turkish words in Hungarian word-stock (300-400 for a minimum, and even more with good alternative Turkic etymologies),[48] and the strong typological similarity of Hungarian and Turkic languages. His Finno-Ugrist opponents strongly rejected not only the fact of such mixing and dual ancestry, but even the theoretical possibility of it. But, in the context of linguistics the use of a strictly binary family tree model proved unfruitful and problematic over the years. We have seen the Uralic tree disintegrate and flatten into a “comb”, and the place of Samoyedic languages and Yukaghir languages within/in relation to the other members is still very problematic. Some scientists questioned seriously even the existence of Uralic as valid language family,[49][50] and attention turned towards the complex areal relations and interactions of Eurasian languages (Uralic and Altaic languages included). In the light of these developments linguists have started to pay due credit to Vámbéry and his work.[51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58]

In connection with Vámbéry's work and the ensuing Ugric-Turkic War it is worth recalling the thoughts of linguist Maarten Mous:[59] „Mixed languages pose a challenge to historical linguistics because these languages defy classification. One attitude towards mixed languages has been that they simply do not exist, and that the claims for mixed languages are instances of a naive use of the term. The inhibition to accept the existence of mixed languages is linked to the fact that it was inconceivable how they could emerge, and moreover their mere existence posited a threat to the validity of the comparative method and to genetic linguistics.”

The "Ugric-Turkic War" was never closed properly. This forced scientists to try to harmonize and synthesize the differing theories somehow. This resulted in the development of a complex national mythology. This combined the Asian roots and origins of Magyars with their European present. Turanism got a new meaning: it became the given name of a variant of Orientalism, which researched Asia and its culture in context of Hungarian history and culture.

Turanism was a driving force in the development of Hungarian social sciences, especially linguistics, ethnography, history, archaeology, and Orientalism, and in the development of Hungarian arts, from architecture to applied and decorative arts. Turanist scientists greatly contributed to the development of Hungarian and international science and arts.

This is a short list of Turkist/Turanist scientists and artists, who have left a lasting legacy in Hungarian culture:

- Ármin Vámbéry (1832-1913) was the founding father of Hungarian Turkology. He founded Europe’s first Turcology department at the Royal University of Pest (present day Eötvös Loránd University). He was a member of the MTA (Hungarian Academy of Sciences).

- János Arany (1817-1882), poet, writer of a large corpus of poems about Hungarian historical past. He supported Vámbéry in the "Ugric-Turkic War". He was a member and secretary general of the MTA.

- Ferenc Pulszky (1814-1897), archaeologist, art historian. He was a member of the MTA and the director of Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum (Hungarian National Museum).[60] He supported Vámbéry in the "Ugric-Turkic War".

- Alajos Paikert (1866-1948) Was the founding father of the "Magyar Mezőgazdasági Múzeum" (Museum of Hungarian Agriculture), and one of the founders of the Turan Society.

- Béla Széchenyi (1837-1918), traveler and explorer of Asia.[61] He was a member of the MTA.

- Jenő Zichy (1837-1906), traveler and explorer of Asia.[62] He was a member of the MTA.

- Géza Nagy (1855-1915), archaeologist, ethnographer.[18][63] He was a member of the MTA.

- Henrik Marczali (1856-1940), historian.[18] He was a member of the MTA.

- Sándor Márki (1853-1925), historian.[18] He was a member of the MTA.

- Lajos Lóczy (1849-1920), geologist, geographer.[18] He was a member of the MTA.

- Jenő Cholnoky (1870-1950), geographer.[18] He was a member of the MTA.

- Vilmos Pröhle (1871-1946), Orientalist, linguist, one of the first researchers of Chinese and Japanese language and literature in Hungary.[18][64]

- Benedek Baráthosi Balogh (1870-1945), Orientalist, ethnographer, traveler.[65]

- Gyula Sebestyén (1864-1946), folklorist, ethnographer.[18] He was a member of the MTA.

- Ferenc Zajti (1886-1961), Orientalist, painter. He was the warden/curator of the Oriental Collection of the Fővárosi Könyvtár (“Library of the Capital” in English, the present day Fővárosi Szabó Ervin Könyvtár). He was the founder of the Magyar Indiai Társaság ( Hungarian India Society). He arranged Rabindranáth Tagore's visit to Hungary in 1926.[66][67]

- József Huszka (1854-1934), art teacher, ethnographer.[18]

- Aladár Körösfői-Kriesch (1863-1920), painter, sculptor, artisan, art theorist, one of the founders of the Gödöllő artists' colony, a leading figure of the Hungarian Arts & Crafts movement.[18]

- Ödön Lechner (1845-1914), architect, who created a new national architectural style from the elements of Hungarian folk art, Persian, Sassanian and Indian art.[18]

- Károly Kós (1883-1977), architect, writer, graphic artist, a leading figure of the Hungarian Arts & Crafts movement.[18]

The idea of a Hungarian Oriental Institute originated from Jenő Zichy.[68] Unfortunately, this idea did not come true. Instead, a kind of lyceum was formed in 1910, called "Turáni Társaság" (The Hungarian Turan Society (also called The Hungarian Asiatic Society)). The Turan society concentrated on Turan as geographic location where the ancestors of Hungarians might have lived.

"The goal of Turanian Society is the cultural and economic progress, confederation, flourishment of all Turanians, i.e. the Hungarian nation and all kindred European and Asian nations, furthermore the geographical, ethnographical, economical etc. research of the Asian continent, past and present. Political and religious issues are excluded. It wishes to accomplish its objectives in agreement with non-Turanian nations."

"Turáni Társaság célja az egész turánság, vagyis a magyar nemzet és a velünk rokon többi európai és ázsiai népek kulturális és gazdasági előrehaladása, tömörülése, erősödése, úgymint az ázsiai kontinens földrajzi, néprajzi, gazdasági stb. kutatása múltban és jelenben. Politikai és felekezeti kérdések kizártak. Céljait a nem turáni népekkel egyetértve óhajtja elérni."[69]

The scholars of the Turan society interpreted the ethnic and linguistic kinship and relations between Hungarians and the so-called Turanian peoples on the basis of the then prevailing Ural-Altaic linguistic theory. The Society arranged Turkish, Finnish and Japanese language courses. The Turan Society arranged and funded five expeditions into Asia till 1914.(The Mészáros-Milleker expedition, the Timkó expedition, the Milleker expedition, the Kovács-Holzwarth expedition, and the Sebők-Schutz expedition.) The Society held public lectures regularly. Lecturers included `Abdu'l-Bahá[70] and Shuho Chiba.[71] After the outbreak of First World War politics ensnarled the work of the Society. In 1916, the Turan Society was redressed into the "Magyar Keleti Kultúrközpont" (Hungarian Eastern Cultural Centre), and direct governmental influence over its operation grew.[1][72] The defeat in the First World War, and the following revolutionary movements and Entente occupation of the country disrupted the operation of the Eastern Cultural Centre, so real work began only in 1920. But the organisation was split into three that year, because of pronounced internal ideological stresses. Those who wanted a more scincelike approach formed the "Kőrösi Csoma-Társaság" (Kőrösi Csoma Society). The more radical political turanists left the Turan Society, and formed the "Magyarországi Turán Szövetség" (Turan Federation of Hungary).

In 1920, Archduke Joseph Francis of Austria (Archduke Joseph Francis Habsburg) became the first patron of the Hungarian Turan Society[73]

Political Turanism

The mechanism of successful propaganda may be roughly summed up as follows. Men accept the propagandist's theology or political theory, because it apparently justifies and explains the sentiments and desires evoked in them by the circumstances. The theory may, of course, be completely absurd from a scientific point of view, but this is of no importance so long as men believe it to be true.[74]

Hungarians and their ancestors lived amongst or in direct contact with Turanian/Turkic peoples from time immemorial to 1908. (A common Hungarian-Turkish border ceased to exist after 1908, in the wake of the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the evacuation of the Sanjak of Novibazar.) These peoples played an eminent role in the birth and formation of Hungarian people, language, culture, state and nation. During the ethnogenesis of Hungarian people Kabar, Jász (Alan), Avar, Bulgar, Besenyő (Pecheneg), Kun (Cuman) tribes and population fragments merged and amalgamated into the Hungarian population.

Hungary warred with the Ottoman Empire for centuries. As a result of a discord of succession Hungary broke up into three parts in the 16th century: one was under Habsburg rule, one became part of the Ottoman Empire (1541.VIII.29.), and the third formed the “keleti Magyar Királyság” (Eastern Hungarian Kingdom)/ “Erdélyi Fejedelemség” (Principality of Transylvania). Erdély became an ally of the Ottomans (1528.II. 29.).[75] The intensive everyday contacts in the one and a half centuries that followed resulted in pronounced Ottoman Turkish influence on Hungarian art and culture from music to jewellery and clothing, from agriculture to warfare. In the last third of the 17th century strife intensified between the Ottomans and the Habsburgs. The main scene of these power struggles was the territory of Hungary. The Ottoman attempts at further territorial expansion failed in the end and the Habsburgs reconquered the Hungarian territories. But there was a conflict in the circles of Hungarian political elite: many members of it were unwilling to swap the Ottoman alliance for direct Habsburg rule. A large group aspired for full independence, but felt Turkish dependence more amenable than Habsburg reign. Thököly's liberation movement and Rákóczi's War of Independence meant the climax of this Turkism. So, as one can see, Turkish orientation had a long tradition in Hungary.

Turkism was reborn in the wake of the 1848-49 War of Independence. During the war Hungary was attacked by the Habsburgs, and many of her ethnic minorities turned against the country. Serious clashes occurred between the Hungarians and the Vlachs of Eastern Hungary and the Serbs of the South. There were serious atrocities against ethnic Hungarians; these events are remembered as "oláhjárások" and "rácjárások" ("Vlach rampages" and "Rascian rampages").[76] Hungary was defeated with the help of Russian military intervention.

These painful events and experiences changed Hungarians' attitudes profoundly: They began to feel themselves insecure and endangered in their own home. From this time on, Pan-Slavism and Pan-Germanism were seen as serious threats to the existence of Hungary and Hungarians. Hungarians looked for allies and friends to secure their position. They turned towards the rivals of the Habsburgs - to Turkey, to the Italians, even to the Prussians - for support and help. Hungarians were interested in a stable, strong and friendly Turkey, capable of preventing Russian and/or Habsburg expansion in the Balkans.

Hungarian political movements and attempts to regain independence proved unfruitful. At the same time, the Habsburgs were unable to acquire the leading position of the German union, and Germany became united under Prussian rule. The Habsburgs took their empire to the verge of collapse with a series of miscalculated political and military moves. This led to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. The Hungarian supporters of the Compromise have argued that the already weakened Austria is no longer a threat to the Hungarians, but can help prevent Slavic expansion.

Despite the Compromise, the Hungarians were ambivalent towards these old-new Austrian allies.

"If the balance of opinion in Hungary were always determined by sober political calculation, this brave and independent people, isolated in the broad ocean of Slav populations, and comparatively insignificant in numbers, would remain constant to the conviction that its position can only be secured by the support of the German element in Austria and Germany. But the Kossuth episode, and the suppression in Hungary itself of the German elements that remained loyal to the Empire, with other symptoms showed that among Hungarian hussars and lawyers self confidence is apt in critical moments to get the better of political calculation and self-control. Even in quiet times many a Magyar will get the gypsies to play to him the song, 'Der Deutsche ist ein Hundsfott' ('The German is a blackguard')." Bismarck, Otto von: Bismarck, the man and the statesman: being the reflections and reminiscences of Otto, Prince von Bismarck. 1898. Vol. II. p. 255-256.[77]

In the half-century prior to the First World War, some Hungarians encouraged Turanism as a means of uniting Turks and Hungarians against the perils posed by the Slavs and Pan-Slavism. However Pan-Turanism was never more than an outrider to the more prevalent Pan-Turkist movement.[78] Turanism helped in the creation of the important Turkish-Austro-Hungarian and Bulgarian-Austro-Hungarian military and strategic alliances.

The movement received impetus after Hungary's defeat in World War I. Under the terms of the Treaty of Trianon (1920.VI.4.), the new Hungarian state constituted only 32,7 percent of the territory of historic, pre-treaty Hungary, and lost 58,4 percent of its total population. More than 3,2 million ethnic Hungarians, one-third of all Hungarians resided outside the new boundaries of Hungary, in the successor states, under oppressive conditions.[79] Old Hungarian cities of great cultural importance like Pozsony, Kassa, Kolozsvár were lost. Under these circumstances no Hungarian government could survive without seeking justice for Magyars and Hungary. Reuniting the Magyars became a crucial point in public life and on the political agenda. Public sentiment became strongly anti-Western, anti-French, and anti-British. Outrage led many to reject Europe and turn towards the East in search of new friends and allies in a bid to revise the terms of the treaty and restore Hungarian power.

"Disappointment towards Europe caused by 'the betrayal of the West in Trianon', and the pessimistic feeling of loneliness, led different strata in society towards Turanism. They tried to look for friends, kindred peoples and allies in the East so that Hungary could break out of its isolation and regain its well deserved position among the nations. A more radical group of conservative, rightist people, sometimes even with an anti-Semitic hint propagated sharply anti-Western views and the superiority of Eastern culture, the necessity of a pro-Eastern policy, and development of the awareness of Turanic racialism among Hungarian people.” in: Uhalley, Stephen and Wu, Xiaoxin eds.: China and Christianity. Burdened Past, Hopeful Future. 2001. p. 219.[80]

Turanism never became official, because it was out of accord with the Christian conservatist ideological background of the regime. But it was used by the government as an informal tool to break the country’s international isolation, and build alliances. Hungary signed treaties of friendship and collaboration with the Republic of Turkey in 1923,[81] with the Republic of Estonia in 1937,[82] with the Republic of Finland in 1937,[83] with Japan in 1938,[84] with Bulgaria in 1941.[85]

In Transylvania, "Turanist ethnographers and folklorists privileged the peasants' cultural 'uniqueness', locating a cultural essence of Magyarness in everything from fishing hooks and methods of animal husbandry to ritual folk songs, archaic, 'individualistic' dances, spicy dishes and superstitions."[86] According to the historian Krisztián Ungváry "With the awakening of Hungarian nationalism at the beginning of the 20th century, the question became topical again. The elite wanted to see itself as a military nation.The claims of certain linguistic researchers regarding the Finno-Ugric relationship were therefore strongly rejected, because many found the idea that their nation was related to a peaceful farming people (the Finns) as insulting...The extremist Turanians insisted on “ties of ancestry” with the Turkish peoples, Tibet, Japan and even the Sumerians, and held the view that Jesus was not a Jew but a Hungarian or a “noble of Parthia”."[87]

Turanism and Hungarian fascism

According to Andrew C. János, while some Hungarian Turanists went as far as to argue they were racially healthier than and superior to other Europeans (including Germans, who were already corrupted by Judaism), others felt more modestly, that as Turanians living in Europe, they might provide an important bridge between East and West and thus play a role in world politics out of proportion of their numbers or the size of their country. This geopolitical argument was taken to absurd extremes by Ferenc Szálasi, head of the Arrow Cross-Hungarist movement, who believed that, owing to their unique historical and geographical position, Hungarians might play a role equal to, or even more important than, Germany in building the new European order, while Szálasi's own charisma might eventually help him supersede Hitler as leader of the international movement.[88]

Ferenc Szálasi, the leader of the Hungarian Arrow Cross Party believed in the existence of a genuine Turanian-Hungarian race (to the extent that his followers went about making anthropological surveys, collecting skull measurements) that was crucial for his ideology of "Hungarism". Szálasi was himself a practicing Catholic and wavered between a religious and a racial basis for Hungarism. The unique vocation of “Turanian” (Turkic) Hungary was its capacity for mediating and uniting both east and west, Europe and Asia, the Christian Balkans and the Muslim Middle East, and from this stemmed its ultimate vocation to lead the world order through culture and example, a task that neither Italy nor Germany was prepared to accomplish.[89]

Turanism after 1945

After the Second World War the Soviet Red Army occupied Hungary. The Hungarian government was placed under the direct control of the administration of the occupying forces. All Turanist organisations were disbanded by the government, and the majority of Turanist publications was banned and confiscated. In 1948 Hungary was converted into a communist one-party state. Turanism was portrayed and vilified as an exclusively fascist ideology, although Turanism's role in the interwar development of far-right ideologies was negligible. The official prohibition lasted until the collapse of the socialist regime in 1989.

Turanism after 1989

Christian Turanists

A Hungarian non-commissioned officer Ferenc Jós Badiny wrote his book ( Jézus Király, a pártus herceg) "King Jesus, the Parthian prince", where he invented the theory of Jesus the Parthian warrior prince. Many Christian Hungarian Turanists held the view that Jesus Christ was not a Jew but a proto-Hungarian or a “noble of Parthia”.[87] The theory of “Jesus, the Parthian prince” are such, or the revivification of real or supposed elements of priest-magicians of ancient “magic” Middle-Eastern world, shamanism, and pagan ancient Hungarian religion. Also some Muslim Turkish Turanists held the view that Muhammad was not an Arab but a Sumerian, and Sumerians are Turanid according to Turanist theses. It is an opportunity for the Christian Turanists to link Jesus to the ancient Middle-Eastern mystery and the ancient pagan Hungarian beliefs. Both Catholic and Protestant religious leaders of Hungary acted against this theory and beliefs.[90]

The Jobbik party and its former president Gábor Vona are uncompromising supporters of Turanism (the ideology of Jobbik considers Hungarians as a Turanian nation).[91]

Great Kurultáj

The Great Kurultáj is a tribal assembly based on the common heritage of the peoples of Central Asian nomadic origin. (Azerbaijani, Bashkirs, Bulgarians, Buryats, Chuvash, Gagauz, Hungarians, Karachays, Karakalpaks, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Manchus, Mongols, Nogai, Tatars, Turks, Turkmen, Uighurs, Üzbeks, Yakuts etc.) It is also a popular tourist attraction in Hungary (from late 2000s) and Central Asia. The first Kurultáj was in Kazakhstan in 2007 and the last one was organized in 2014 at Bugac, Hungary.[92][93]

In the 1990s, a well developed souvenir and merchandise business has grown around Turanism, traditionalist and historical reenactment groups, which is quite similar to other well known international examples of business of this kind. According to the opinion of Hungarian researcher Igaz Levente this merchandise industry grown around modern Hungarian Turanism became a kind of business, which he called "Szittya biznisz" (Scythian business), and it has not got much to do with ancient Hungarian traditions.[94]

Pseudoscientific theories

Hungarian Turanism has been characterized by pseudoscientific theories.[95][96] According to these theories, Hungarians share supposed Ural-Altaic origins with Bulgarians, Estonians, Mongols, Finns, Turkic peoples, and even Japanese people and Koreans.[95] Origins of the Hungarian people with the Huns, Scythians or even Sumerians have been suggested by proponents of these theories.[97][98] Such beliefs gained widespread support in Hungary in the interwar period.[98] Though since widely discredited, these theories have regained support among certain Hungarian political parties, in particular among Jobbik and certain factions of Fidesz.[96]

See also

- Curse of Turan

- Pál Teleki

- Turanism (similar Turkic ideology)

- Hungarian neopaganism

- Ármin Vámbéry

- Ignác Goldziher

Further reading

- Akcah, Emel; Korkut, Umut (2012). "Geographical Metanarratives in East-Central Europe: Neo-Turanism in Hungary" (PDF). Eurasian Geography and Economics. 53 (5): 596–614. doi:10.2747/1539-7216.53.5.596.

- Joseph Kessler Turanism and Pan-Turanism in Hungary: 1890-1945 (University of California, Berkeley, PhD thesis, 1967)

References

- "FARKAS Ildikó: A magyar turanizmus török kapcsolatai ("The Turkish connections of Hungarian Turanism")". www.valosagonline.hu [Valóság (2013 I.-IV)]. 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- Anonymus: Gesta Hungarorum. http://mek.oszk.hu/02200/02245/02245.htm

- Kézai Simon mester Magyar krónikája. http://mek.oszk.hu/02200/02249/02249.htm

- "...amikor Kőrösi elindult a magyarok őshazáját és a ‘hátramaradt magyarokat’ megkeresni, úgy vélte, azokra valahol Közép-Ázsiában, illetve az ujgurok között bukkanhat rá..." in: Kőrösi Csoma Sándor élete. http://csoma.mtak.hu/hu/csoma-elete.htm

- GYÖRFFY György: István király és műve. 1983. Gondolat Könyvkiadó, Budapest, p. 252.

- KOVÁCSNÉ CSÁNYI Bernadett: Honfoglalás kori, valamint magyar és székely populációk apai ági genetikai kapcsolatrendszerének vizsgálata. http://www2.sci.u-szeged.hu/fokozatok/PDF/Kovacsne_Csanyi_Bernadett/tezisfuzet_magyar_csanyiB.pdf

- HAJDÚ Péter: Ancient culture of the Uralian peoples, Corvina, 1976, p. 134

- ZIMONYI István: A magyarság korai történetének sarokpontjai. Elméletek az újabb irodalom tükrében. 2012. http://real-d.mtak.hu/597/7/dc_500_12_doktori_mu.pdf

- EB on Matthias Alexander Castrén. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/98799/Matthias-Alexander-Castren

- "Search". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Traian Sandu, Vers un profil convergent des fascismes ?: "Nouveau consensus" et religion politique en Europe centrale, Editions L'Harmattan,2010, p. 213

- "...In addition, as the cornerstone for racial nationalism, Hungarian "Turanism" came into being. This pseudoscientific ideology strove to prove the existence and superiority of a unified Hungarian "race" and therefore inevitably incorporated an anti-Jewish aspect." in: Zoltán VÁGI, László CSŐSZ, Gábor KÁDÁR: The Holocaust in Hungary: Evolution of a Genocide. p.XXXIV.

- "While Turanism was and remained little more than a fringe ideology of the Right, the second orientation of the national socialists, pan-Europaism, had a number of adherents, and was adopted as the platform of several national socialist groups." JANOS, Andrew C.: The Politics of Backwardness in Hungary, 1825-1945. 1982. p.275.

- "Magyarországon az 1944-ben uralomra jutott Nemzetszocialista Párt több tételt átvett a turanizmus eszmeköréből, aminek következtében a turanizmus népszerűsége erősen lecsökkent, majd a szocializmusban „fasisztává” minősült."/"In Hungary the Nationsocialist Party which ascended to power in 1944, took over several theses from Turanism's range of ideas, and as a result the popularity of Turanism strongly dwindled, and then in the socialist era it was labelled as "fascist"."/ in: "turanizmus". lexikon.katolikus.hu [Magyar Katolikus Lexikon (Hungarian Catholic Lexicon)]. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- KATIČIĆ, Radoslav: A contribution to the general theory of comparative linguistics. 1970. p.10.

- MÜLLER, Friedrich Max: The languages of the seat of war in the East. With a survey of the three families of language, Semitic, Arian and Turanian. 1855.https://archive.org/details/languagesseatwa00mlgoog

- MÜLLER, Friedrich Max: Letter to Chevalier Bunsen on the classification of the Turanian languages. 1854. https://archive.org/details/cu31924087972182

- Magyar Életrajzi Lexikon. http://mek.oszk.hu/00300/00355/html/index.html

- VÁMBÉRY Ármin: Küzdelmeim. 1905. http://mek.oszk.hu/03900/03975/03975.pdf

- STRAHLENBERG, Philipp Johann von: An historico-geographical description of the north and east parts of Europe and Asia http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/010825073

- " Die Stammväter der Magyaren in Ungarn waren, wie die Geschichte leise andeutet und der Ur-Kern ihrer Sprache zu bestätigen scheint, ein Gemisch von Türken und Hyperboreern. Ihre häufigen Wanderungen hatten noch fernere Amalgamation mit Indo-Germanischen Völkern zu Folge, und so entwickelte sich der heutige Ungar, aus mancherlei Völker-Elementen eben so geläutert und männlich schön hervorgegangen, wie sein heutiger Nachbar und Ur-Verwandter, der Osmane. " SCHOTT, Wilhelm: Versuch über die Tatarischen Sprachen. 1836. p.7.

- HERMAN Ottó: Petényi J. S. a magyar tudományos madártan megalapítója. http://mek.oszk.hu/12100/12102/12102.pdf

- BUZINKAY Géza: A magyar irodalom és sajtó irányítása a Bach-korszakban. http://epa.oszk.hu/00000/00021/00290/pdf/MKSZ_EPA00021_1974_90_03-04_269-293.pdf

- CSOHÁNY János: Leo Thun egyházpolitikája. In: Egyháztörténeti Szemle. 11/2. 2010. http://www.uni-miskolc.hu/~egyhtort/cikkek/csohany-thun.htm

- Az Entwurf hatása a történelemtanításra. http://janus.ttk.pte.hu/tamop/tananyagok/tort_tan_valt/az_entwurf_hatsa_a_trtnelemtantsra.html

- BOLVÁRI-TAKÁCS Gábor: Teleki József, Sárospatak és az Akadémia. http://www.zemplenimuzsa.hu/05_2/btg.htm

- VEKERDI László: Egy könyvtár otthonai, eredményei és gondjai. http://tmt.omikk.bme.hu/show_news.html?id=3135&issue_id=390

- Vasárnapi Ujság. 1858.XII.19. http://epa.oszk.hu/00000/00030/00251/pdf/VU-1858_05_51_12_19.pdf

- KOS, Franz Josef: Die Politik Österreich-Ungarns während der Okkupationskrise 1874/75-1879. Böhlau, Köln-Wien, 1984,p.42, p.51.

- PALOTÁS Emil: Okkupáció–annexió 1878–1908. http://www.tankonyvtar.hu/hu/tartalom/historia/95-01/ch08.html

- "The Great Powers and the "Eastern Question"". Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- GOOD, David F.: The Economic Rise of the Habsburg Empire, 1750-1914. 1984. p.82.

- "A kiegyezéses rendszert ugyanis a társadalom szélesebb körei, a parasztság, a kispolgárság – akár igazuk volt, akár nem – elutasították. Ennek folytán, ha a kiegyezéses rendszert fenn akarták tartani, a választójogot nem lehetett bővíteni, mert akkor a kiegyezés ellenfelei kerültek volna parlamenti többségbe." in: GERGELY András: Az 1867-es kiegyezés. http://www.rubicon.hu/magyar/oldalak/az_1867_es_kiegyezes

- CIEGER András: Kormány a mérlegen - a múlt században.http://c3.hu/scripta/szazadveg/14/cieger.htm

- http://mtda.hu/books/zajti_ferenc_magyar_evezredek.pdf

- "Kultúra, nemzet, identitás". Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- DRIEM, George van: Languages of the Himalayas: an ethnolinguistic handbook. 1997. p.161-162.

- HANEBRINK, Paul: Islam, Anti-Communism, and Christian Civilization: The Ottoman Menace in Interwar Hungary, Cambridge Journals

- Steven Totosy de Zepetnek, Louise O. Vasvari: Comparative Hungarian Cultural Studies (page:48)

- VÁMBÉRY Ármin: Magyar és török-tatár szóegyezések." In Nyelvtudományi közlemények VIII. p. 109-189.http://www.nytud.hu/nyk/reg/008.pdf

- Angela MARCANTONIO, Pirjo NUMMENAHO, Michela SALVAGNI: THE ”UGRIC-TURKIC BATTLE”: A CRITICAL REVIEW. http://www.kirj.ee/public/va_lu/l37-2-1.pdf

- THÚRY József: Az ugor-magyar theoria. 1. rész. 1884. http://epa.oszk.hu/02300/02392/00030/pdf/EPA02392_egy_phil_kozl_08_1884_02_131-158.pdf

- THÚRY József: Az ugor-magyar theoria. 2. rész. 1884. http://epa.oszk.hu/02300/02392/00031/pdf/EPA02392_egy_phil_kozl_08_1884_03-04_295-311.pdf

- THÚRY József: Az ugor-magyar theoria. 3. rész. 1884. http://epa.oszk.hu/02300/02392/00032/pdf/EPA02392_egy_phil_kozl_08_1884_05_416-440.pdf

- HUNFALVY Pál: Magyarország ethnographiája. http://www.fszek.hu/mtda/Hunfalvy-Magyarorszag_ethnographiaja.pdf

- VÁMBÉRY Ármin: A magyarok eredete. Ethnologiai tanulmány.1882.http://digitalia.lib.pte.hu/?p=3265

- SÁNDOR Klára: Nemzet és történelem. XXVI. rész. http://galamus.hu/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=44796:nemzet-es-toertenelem&catid=68:cssandorklara&Itemid=105

- RÓNA-TAS, András and BERTA, Árpád: West Old Turkic. Turkic Loanwords in Hungarian. 2011.

- PUSZTAY János: The so-called Uralic original home (Urheimat) and the so-called Proto-Uralic. TRAMES 2001. 5(55/50), 1, p.75–91. https://www.digar.ee/viewer/en/nlib-digar:14601/147675/page/83

- AGOSTINI, Paolo: LANGUAGE RECONSTRUCTION – APPLIED TO THE URALIC LANGUAGES. http://hrcak.srce.hr/file/161182

- SÁNDOR Klára: A magyar-török kétnyelvűség és ami mögötte van. http://web.unideb.hu/~tkis/sl/sk_tm.

- FEHÉR Krisztina: A családfamodell és következményei. http://mnytud.arts.klte.hu/mnyj/49/08feherk.pdf

- RÓNA-TAS András: Morphological embedding of Turkic verbal bases in Hungarian. In:JOHANSON, Lars and ROBBEETS, Martine Irma eds.: Transeurasian verbal morphology in a comparative perspective: genaology, contact, chance. 2010. p.33-42.

- CSATÓ, Éva Ágnes: Perceived formal and functional equivalence: The Hungarian ik-conjugation. In: ROBBEETS, Martine Irma & BISANG, Walter eds.: Paradigm change: In the Transeurasian languages and beyond. 2014. p. 129-139.

- KORTLANDT, Frederik: An outline of Proto-Indo-European. http://www.kortlandt.nl/publications/art269e.pdf

- PARPOLA Asko: The problem of Samoyed origins in the light of archaeology: On the formation and dispersal of East Uralic (Proto-Ugro-Samoyed) http://www.sgr.fi/sust/sust264/sust264_parpola.pdf

- HÄKKINEN Jaakko: Early contacts between Uralic and Yukaghir. http://www.sgr.fi/sust/sust264/sust264_hakkinenj.pdf

- JANHUNEN Juha: Proto-Uralic - what, where, and when? http://www.sgr.fi/sust/sust258/sust258_janhunen.pdf

- MATRAS, Yaron and BAKKER, Peter eds.: The Mixed Language Debate: Theoretical and Empirical Advances 2003. p. 209.

- "Magyar Életrajzi Lexikon 1000-1990". Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- http://mek.oszk.hu/05300/05389/pdf/Loczy_Szechenyi_emlekezete.pdf

- "Magyar Életrajzi Lexikon 1000-1990". Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- http://epa.oszk.hu/01600/01614/00002/pdf/nyjame_02_1959_051-061.pdf

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-03-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Barathosi Balogh Benedek Expo". Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- SZABÓ Lilla: Zajti Ferenc festőművész és Medgyaszay István építész magyarságkutatásai. in: Kultúra, nemzet, identitás. A VI. Nemzetközi Hungarológiai Kongresszuson (Debrecen, 2006. augusztus 23–26.) elhangzott előadások. 2011.http://mek.oszk.hu/09300/09396/09396.pdf

- "Zajti Ferenc (Terebess Ázsia Lexikon)". Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- VINCZE Zoltán: Létay Balázs, a magyar asszirológia legszebb reménye http://www.muvelodes.ro/index.php/Cikk?id=155

- "http://mtdaportal.extra.hu/books/teleki_pal_a_turani_tarsasag.pdf

- "'Abdu'l-Bahá Budapesten » Magyarországi Bahá'í Közösség »". Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Vasárnapi Ujság. 1913.III.16. http://epa.oszk.hu/00000/00030/03094/pdf/VU_EPA00030_1913_11.pdf

- "Művelődés". Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Őstörténet és nemzettudat, 1919-1931 - Digitális Tankönyvtár". Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- HUXLEY, Aldous: Writers and Readers. 1936.

- MAKKAI László, MÓCSY András eds.: Erdély története. Első kötet. 1986. p.409-421. http://mek.oszk.hu/02100/02109/html/93.html

- BOTLIK József: Magyarellenes atrocitások a Kárpát-medencében. http://adattar.vmmi.org/fejezetek/1896/07_magyarellenes_atrocitasok_a_karpat_medenceben.pdf

- BISMARCK, Otto von: Bismarck, the man and the statesman: being the reflections and reminiscences of Otto, Prince von Bismarck. 1898. Vol. II. p. 255-256.

- EB on Pan-Turanianism. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/440695/Pan-Turanianism

- PORTIK Erzsébet-Edit: Erdélyi magyar kisebbségi sorskérdések a két világháború között. In: Iskolakultúra 2012/9. p. 60-66. http://epa.oszk.hu/00000/00011/00168/pdf/EPA00011_Iskolakultura_2012-9_060-066.pdf

- UHALLEY, Stephen and WU, Xiaoxin eds.: China and Christianity. Burdened Past, Hopeful Future. 2001. p. 219.

- 1924. évi XVI. törvénycikk a Török Köztársasággal Konstantinápolyban 1923. évi december hó 18. napján kötött barátsági szerződés becikkelyezéséről. http://www.1000ev.hu/index.php?a=3¶m=7599

- 1938. évi XXIII. törvénycikk a szellemi együttműködés tárgyában Budapesten, 1937. évi október hó 13. napján kelt magyar-észt egyezmény becikkelyezéséről. http://www.1000ev.hu/index.php?a=3¶m=8078

- 1938. évi XXIX. törvénycikk a szellemi együttműködés tárgyában Budapesten, 1937. évi október hó 22. napján kelt magyar-finn egyezmény becikkelyezéséről. http://www.1000ev.hu/index.php?a=3¶m=8084

- 1940. évi I. törvénycikk a Budapesten, 1938. évi november hó 15. napján kelt magyar-japán barátsági és szellemi együttműködési egyezmény becikkelyezéséről. http://www.1000ev.hu/index.php?a=3¶m=8115

- 1941. évi XVI. törvénycikk a szellemi együttműködés tárgyában Szófiában az 1941. évi február hó 18. napján kelt magyar-bolgár egyezmény becikkelyezéséről. http://www.1000ev.hu/index.php?a=3¶m=8169

- László Kürti The Remote Borderland: Transylvania in the Hungarian Imagination, SUNY Press, 2001, p.97

- See Ungváry

- JÁNOS, Andrew C.: East Central Europe in the Modern World Stanford University Press, 2002 pp.185-186

- PAYNE, Stanley: A History of Fascism, 1914-1945. 1995. p.272.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-05-30. Retrieved 2012-06-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.jobbik.com/jobbik_news/europe/3198.html Archived December 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Information". Kurultáj. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Deputy house speaker greets Asian ethnic groups in Parliament". Politics.hu. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Barna Borbas (5 May 2013). "Élet a szittya bizniszen túl – utak a magyar hagyományőrzésben" (in Hungarian). Heti Valasz. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- Nagy, Zsolt (2017). Great Expectations and Interwar Realities: Hungarian Cultural Diplomacy, 1918-1941. Central European University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-9633861943.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Flowering of Pseudo-Science In Orbán's Hungary". Hungarian Spectrum. August 13, 2018.

- Laruelle, Marlene (2015). Eurasianism and the European Far Right: Reshaping the Europe–Russia Relationship. Lexington Books. p. 14. ISBN 978-1498510691.

According to their historical understanding, explained by the pseudo-scientific approach of the Turanist movement, Hungarians belonged to the Orient

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Botz-Bornstein, Thorsten (2017). Organic Cinema: Film, Architecture, and the Work of Béla Tarr. Berghahn Books. p. 145. ISBN 978-1785335679.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Ungváry, Krisztián (5 February 2014). "Turanism: the 'new' ideology of the far right". The Budapest Times. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015.