Egyptian nationalism

Egyptian nationalism is the nationalism of Egyptians and Egyptian culture.[1] Egyptian nationalism has typically been a civic nationalism that has emphasized the unity of Egyptians regardless of ethnicity or religion.[1] Egyptian nationalism first manifested itself in Pharaonism beginning in the 19th century that identified Egypt as being a unique and independent political unit in the world since the era of the Pharaohs in ancient Egypt.[1]

History

Late 19th century

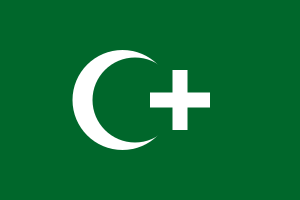

Both the Arabic language spoken in modern Egypt and the ancient Egyptian language are Afroasiatic languages.[2] The rule of Muhammad Ali of Egypt led Egypt into an advanced level of socioeconomic development in comparison with Egypt's neighbours, which along with the discoveries of relics of ancient Egyptian civilization, helped to foster Egyptian identity and Egyptian nationalism.[1] The Urabi movement in the 1870s and 1880s was the first major Egyptian nationalist movement that demanded an end to the alleged despotism of the Muhammad Ali family and demanded curbing the growth of European influence in Egypt, it campaigned under the nationalist slogan of "Egypt for Egyptians".[1]

One of the key figures in opposing British rule was the Egyptian Jewish journalist Yaqub Sanu whose cartoons from 1870s onward satirizing first the Khedive, Ismail the Magnificent, and then Egypt's British rulers as bumbling buffoons were very popular in the 19th century.[3] Sanu was the first to write in Egyptian Arabic, which was intended to appeal to a mass audience, and his cartoons could be easily understood by even the illiterate.[3] Sanu had established the newspaper Abu-Naddara Zarqa, which was the first newspaper to use Egyptian Arabic on 21 March 1877 and one of his cartoons which mocked Ismail the Magnificent for his fiscal extravagance which caused Egypt's bankruptcy in 1876, led Ismail who did not appreciate the cartoon, to order his arrest.[4] Sanu fled to Paris, and continued to publish Abu-Naddara Zarqa there, with its issues being smuggled into Egypt until his death in 1912.[5]

Opposed to the British occupation of his homeland, Sanu from 1882 drew cartoons which depicted the British as "red locusts" devouring all of Egypt's wealth, leaving nothing behind for the Egyptians.[6] Though banned in Egypt, Abu-Naddara Zarqa was a very popular underground newspaper with Sanu's cartoons being especially popular.[7] Other cartoons drawn by Saunu with captions in Arabic and French depicted La Vieux Albion (England) as a hideous hag together with her even more repulsive son John Bull, who was always shown as an ignorant, uncouth and drunken bully pushing around ordinary Egyptians.[8] Sanu's Egyptian nationalism was based on loyalty to Egypt as a state and geographic entity as he presented Egypt as a tolerant place where Muslims, Christians and Jews were all united by a common love of al-watan ("the homeland").[9] Against the claim made by British officials like Lord Cromer who claimed the British occupation of Egypt was necessary to protect Egypt's Jewish and Christian minorities from the Muslim majority, Sanu wrote that as an Egyptian Jew he did not feel threatened by the Muslim majority, saying in a speech in Paris "The Quran is not a book of fanaticism, superstition or barbarity."[9]

20th century

After the British occupation of Egypt in 1882, Egyptian nationalism became focused upon ending British colonial rule.[1] They had support from Liberals and Socialists in Britain. Wilfrid Scawen Blunt was a leading critic of British imperialism in Africa, as expressed in three widely circulated books: The Secret History of the English Occupation of Egypt... (1907), Gordon at Khartoum (1911), and My Diaries: Being a Personal Narrative of Events, 1888-1914 (2 vols. 1919-20). Historian Robert O. Collins says:

- The most vigorous English advocate of Egyptian nationalism, Blunt was both arrogant and irascible, his works scathing, discursive, and at times utterly ridiculous. Immature and unfair, both he and his writings must be used with caution, but even the dullest of men will come away stimulated if not aroused and with fresh insights to challenge the sometimes smug attitudes of British officials in Whitehall and Cairo. Of course, to them Blunt was anathema if not disloyal and Edward Malet, the British Consul-General at Cairo from 1879 to 1883, replied to Blunt's charges in his posthumously published Egypt, 1879-1883 (London, 1909).[10]

Mustafa Kamil Pasha, a leading Egyptian nationalist of the early 20th century, was greatly influenced by the example of Meiji Japan as an 'Eastern' state that had successfully modernized for Egypt and from the time of the Russian-Japanese war consistently urged in his writings that Egypt emulate Japan.[11] Kamil was also a Francophile like most educated Egyptians of his generation, and the French republican values of liberté, égalité, fraternité influenced his understanding of what it meant to be Egyptian as Kamil defined Egyptianess in terms of loyalty to Egypt.[12] Kamil together with other Egyptian nationalists helped to redefine loyalty to al-watan ("the homeland") in terms stressing the importance of education, nizam (order), and love of al-watan, implicitly criticizing the state created by Mohammad Ali the Great, which was run on very militarist lines.[12] After the Entene Cordial of 1904 ended hopes of French support for Egyptian independence, a disillusioned Kamil looked east towards Japan as a model, defining Egypt as an "Eastern" country occupied and exploited by "Western" Great Britain, and suggested in terms that anticipated later Third World nationalism that Egyptians had more in common with people from other places occupied by the Western nations such as India (modern India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh) and the Netherlands East Indies (modern Indonesia) than they did with the nations of Europe.[13]

Egyptian nationalism reached its peak in popularity in 1919 when revolution against British rule took place in response to wartime deprivations imposed by the British upon Egypt during World War I.[1] Three years of protest and political turmoil followed until Britain unilaterally declared the independence of Egypt in 1922 that was a monarchy, though Britain reserved several areas for British supervision.[1] During the period of the Kingdom of Egypt, Egyptian nationalists remained determined to terminate the remaining British presence in Egypt.[1] One of the more celebrated cases of Egyptian nationalism occurred in December 1922 when the Egyptian government laid claim to the treasures found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun, which had been discovered by a British archaeologist Howard Carter in November 1922, arguing that they belonged to Egypt and Carter could not take them to Britain as he planned.[14] The dispute finally led to the Egyptians posting an armed guard outside of Tutankhaum's tomb to prevent Carter from entering it.[15] In February 1924, the Egyptian government seized control of the tomb and with it all of the artifacts found there, saying that they belonged to Egypt.[16] On 6 March 1924, the Prime Minister Saad Zaghloul formally opened to Tutakhuam's tomb to the Egyptian public in an elaborate ceremony held at night with the sky lit up by floodlights, which reportedly attracted the largest crowd seen in Luxor.[16] The reopening turned into an anti-British demonstration when the British High Commissioner, Field Marshal Allenby, arrived when the crowd demanding immediate British withdrawal from Egypt.[16] The dispute over who owned King Tutankhamun's treasures took place against the backdrop of a movement in the Egyptian intelligentsia known as Pharaonism which extolled ancient Egypt as a national symbol and portrayed Egypt as a Mediterranean nation with links to Europe instead of a Near Eastern nation.[17]

Though Arab nationalism rose as a political force in the 1930s, there remained a strong regional attachment to Egypt by those who advocated cooperation with other Arab or Muslim neighbours.[18] Traditionally, the term "Arab" had a derogatory meaning in Egypt despite the fact that 90% of Egyptians speak Arabic as their first language, as Egyptians tended to view people from other Arab countries as backward, ignorant and crude.[19] Egyptian nationalists in the early 20th century were usually opposed to the idea of Egypt becoming part of a pan-Arab state.[19] Saad Zaghloul, the founder of the Wafd Party, was hostile towards pan-Arabism, saying: "If you add one zero to another, and then to another, what sum will you get?"[19] Pan-Arab nationalists, who in the early 20th century tended to be Christians from the Levant, usually excluded Egypt from their planned nation under the grounds that: "Egyptians do not belong to the Arab race".[19] The nationalistic and fascistic Young Egypt Society in the 1930s led by Ahmed Hussein advocated British withdrawal from Egypt and the Sudan, and promised to unite the Arab world under the leadership of Egypt, through the Young Egypt Society made it clear in the proposed empire, it was Egypt that would dominate.[20] At the same time, "Pharaohism" was condemned by Hassan al-Banna, the founder and Supreme Guide of the fundamentalist Muslim Brotherhood, as glorying a period of jahiliyyah ("barbarous ignorance"), which is the Islamic term for the pre-Islamic past.[21] In a 1937 article, Banna dismissed "Pharaohism" for glorying the "pagan reactionary Pharaohs" like Akhenaton, Ramses the Great and Tutakhuam instead of the Prophet Mohammad and his companions and for seeking to "annihilate" Egypt's Muslim identity.[21]

In January 1952, British forces attacked a police station leaving around 50 people dead. The capital of Egypt, Cairo, overflowed with British anti-violence in a riot on 26 January 1952 known as the "Black Saturday" riot. The Black Saturday riots led to the development of the Free Officer movement, consisting of a thousand “middle-level” officers, overthrowing King Farouk.[22] After the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 that overthrew the monarchy and established a republic, Gamal Abdel Nasser rose to power on themes that mixed Arab and Egyptian nationalism.[18] Nasser saw Egypt as the leader of the Arab states and saw Egypt's role as promoting Arab solidarity against both the West and Israel.[18] Nasser's first priority was end subordination to Britain which meant most urgently the removal of British bases privileges and acquire greater control over the Suez Canal.[22]

In 1952 Nasser produced a work that was half autobiographical and half programmatic entitled The Philosophy of the Revolution.[23] It offers and account to how he and other officers who overthrew the monarchy on July 23 of that year came to a decision to seize power and how they planned to use their newly won power.[22] Under Nasser, Egypt's Arab identity was greatly played up, and Nasser promoted a policy of pan-Arabism, arguing that all of the Arab peoples should be united together in a single state under his leadership.[24] Egypt was briefly united with Syria under the name the United Arab Republic from 1958 until 1961 when Syria abandoned the union.[18] Nasser saw himself as the successor of Mohammad Ali the Great, the illiterate Albanian tobacco merchant turned Ottoman vali (governor) of Egypt, who had sought to found a new dynasty to rule the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century.[25] Nasser came to embrace pan-Arabism as the best way of justifying a greater Egypt that would stretch from the Atlantic to Indian oceans.[25]

After the Six Day War of 1967, Nasser started to downplay pan-Arab nationalism, and instead promoted an "Egypt first" policy, a policy that was continued by his successor Sadat who took the "Egypt first" policy far further than Nasser had been prepared to go.[26] In March 1969, Nasser began the War of Attrition with Israel, a policy of launching air raids, artillery bombardments and commando raids intended to make the Sini too costly for Israel to hold, and which led Israel to retaliate likewise with its own air raids, artillery bombardments and commando raids into Egypt.[27] The War of Attrition turned the cities of the Suez Canal into ghost towns, Egyptian military expenditure consumed a quarter of the national income while Egypt was deprived of the revenue from the Suez Canal tolls.[28] After the Israeli Air Force began bombing the cities in the Nile river valley in late 1969, Nasser forced the Soviet Union to deploy its air defense units to Egypt in January 1970 by threatening to resign in favor of a pro-American politician.[29] Through the Soviet forces had arrived in Egypt to assist with the War of Attrition, for many ordinary Egyptians it was a humiliating reminder of their inability to counter the Israeli Air Force. The War of Attrition period of 1969-70 was a period of rapidly falling living standards in Egypt and led many ordinary Egyptians to complain that Egypt's role as the champion of Arab nationalism led to a seemingly endless confrontation with Israel whose costs were too high.[28] In August 1970, Nasser ended the War of Attrition by signing a ceasefire with Israel, and in September 1970 hosted a pan-Arab summit to end the Black September war in Jordan.[30] When Nasser was criticized for signing a ceasefire with Israel by King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, he exploded in rage: "You issue statements, but we have to fight. If you want to liberate, then get in line in front of us...but we have learnt caution after 1967 and after the Yemenis dragged us into their affairs in 1967 and the Syrians into war in 1967".[30]

Nasser's successors, Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak de-emphasized Arab nationalism and re-emphasized Egyptian nationalism based on Egypt's distinctiveness within the Arab world.[18] Sadat upon taking office in 1970 announced that his first policy would be "Egypt first", saying quite openly that Egyptian national interests would take precedence over pan-Arab goals.[31] In December 1970, Sadat announced in a speech that Egypt would be willing to make peace with Israel provided the latter returned the Sinai peninsula, making no mention of the West Bank, Gaza Strip or the Golan Heights.[31] In June 1972, Sadat expelled all of the Soviet forces in Egypt, a move which was very popular with the Egyptian people as he announced that Egypt could now defend its air space on its own.[29] After the 1973 October War had boosted his image, Sadat began a wholesale attack on Nasser's legacy, including his Pan-Arabist policies, which were portrayed as having dragged Egypt into poverty, a long grinding war in Yemen, and subservience to the Soviet Union.[28] In contrast to the secularist Nasser, Sadat began a policy of playing up Egypt's Muslim identity, having the constitution amended in 1971 to say that Sharia law was "a main source of all state legislation" and in 1980 to say that Sharia law was the main source of all legislation.[28] Through Sadat was not an Islamic fundamentalist, under his rule Islam started to be portrayed as the cornerstone of Egyptian national identity.[28] Sadat had chosen to launch what Egyptians call the Ramadan War in 1973 during the holy month of Ramadan and the code-name for the initial assault on the Israeli Bar Lev Line on the Suez Canal was Operation Badr, after the Prophet Mohammad's first victory, both gestures that would have been unthinkable under Nasser as Sadat chose to appeal to Islamic feelings.[32] Sadat and Mubarak also abandoned Nasser's Arab nationalist conflict with Israel and the West.[18] At times, Sadat chose to engage in "Pharaohism" as when he arranged for the mummy of Ramses the Great to be flown to Paris for restoration work in 1974, he insisted that the coffin carrying his corpse be greeted at Charles de Gaulle airport with a 21-gun salute as befitting a head of state.[33] However, Sadat's "Pharaonism" was mostly limited to the international stage, and rarely occurred domestically, as he closed the mummy room at the Egyptian Museum for supposedly Islamic sensibilities, though he reportedly remarked in private that "Egyptian kings are not be made a spectacle of".[33]

Recent years

The Arab Spring in Egypt in 2011 that forced the resignation of Mubaruk from power and resulted in dualparty elections, has raised questions over the future of Egyptian nationalism.[34] In particular the previous secular regimes of Nasser, Sadat, and Mubarak avoided direct religious conflicts between the majority Muslims and the minority Coptic Christians through their emphasis on secular Egyptian nationalist culture, while concerns have been raised on whether this Egyptian nationalist culture will remain with the political changes caused by the Arab Spring.[35] This has especially become an issue after a series of episodes of Muslim-Christian violence erupted in Egypt in 2011.[35] In 2015, a surprise hit on Egyptian television was Harat al-Yehud, which was set in Cairo's Jewish quarter in 1948, and was noted as being the first time that Egyptian Jews were portrayed in a favorable light, instead of the villains that have normally portrayed as since the 1950s.[36]

See also

References

- Motyl 2001, p. 138.

- David P. Silverman. Ancient Egypt. New York, New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 1997. p. 234.

- Fahamy 2008, p. 170-174.

- Fahamy, p. 172.

- Fahamy 2008, p. 172.

- Fahamy 2008, p. 174.

- Fahamy 2008, p. 172=173.

- Fahamy, 2008 & p173-175.

- Fahamy, 2008 & p178.

- Robert O. Collins, "Egypt and the Sudan" in Robin W. Winks, ed., The Historiography of the British Empire-Commonwealth: Trends, Interpretations and Resources (Duke U.P. 1966) p 282. The Malet book is online

- Laffan 1999, p. 268-270.

- Laffan 1999, p. 271.

- Laffan 1999, p. 273.

- Parkinson 2008, p. 6.

- Parkinson 2008, p. 7.

- Wood 1998, p. 183.

- Wood 1998, p. 181.

- Motyl 2001, p. 139.

- Karsh 2006, p. 144.

- Wood 1998, p. 184.

- Wood 1998, p. 185.

- Hunt, Michael H. (2004). The World Transformed: 1945 to the present. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 284. ISBN 9780199371020.

- Karsh 2006, p. 147.

- Karsh 2006, p. 144-145.

- Karsh 2006, p. 148.

- Karsh 2006, p. 166-167.

- Karsh 2006, p. 171 & 194-195.

- Karsh 2006, p. 171.

- Karsh 2006, p. 195.

- Karsh 2006, p. 167.

- Karsh 2006, p. 168.

- Karsh 2006, p. 171-172.

- Wood 1998, p. 186.

- Lin Noueihed, Alex Warren. The Quest for the Arab Spring: Revolution, Counter-Revolution and the Making of a New Era. Yale University Press, 2012. pp. 125–128.

- Lin Noueihed, Alex Warren. The Battle for the Arab Spring: Revolution, Counter-Revolution and the Making of a New Era. Yale University Press, 2012. pp. 125–128.

- "Egypt's bumbling police get their man, at least on television". The Economist. 31 May 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

Bibliography

- Fahamy, Ziad "Francophone Egyptian Nationalists, Anti-British Discourse, and European Public Opinion, 1885-1910: The Case of Mustafa Kamil and Ya'qub Sannu'" from Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Volume 28, Number 1, 2008 p. 170-183

- Karsh, Efraim (2006). Islamic Imperialism A History. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10603-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laffan, Michael "Mustafa and the Mikado: A Francophile Egyptian's turn to Meiji Japan" p. 269-286 from Japanese Studies, Vol 19, # 3, 1999 p. 269-270

- Motyl, Alexander J. (2001). Encyclopedia of Nationalism, Volume II. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-227230-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lin Noueihed, Alex Warren. The Battle for the Arab Spring: Revolution, Counter-Revolution and the Making of a New Era. Yale University Press, 2012.

- "Parkinson, Brian "Tutankhamen on Trial: Egyptian Nationalism and the Court Case for the Pharaoh's Artifacts" from The Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Volume 44, 2008 p. 1-8.

- Wood, Michael "The Use of the Pharaonic Past in Modern Egyptian Nationalism" p. 179-196 from The Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Volume 35, 1998.