Turkic migration

Turkic migration refers to the expansion of the Turkic tribes and Turkic languages into Central Asia, Eastern Europe and West Asia, mainly between the 6th and 11th centuries.

Identified Turkic tribes were known by the 6th century, and by the 10th century most of Central Asia was settled by Turkic tribes. The Seljuq dynasty settled in Anatolia starting in the 11th century, ultimately resulting in permanent Turkic settlement and presence there. Meanwhile, other Turkic tribes either ultimately formed independent nations, such as Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, or new enclaves within other nations, such as Chuvashia, Bashkortostan, Tatarstan, the Crimean Tatars, the Uyghurs in China, and the Sakha Republic Siberia.

Origin theories

Proposals for the homeland of the Turkic peoples and their language are far-ranging, from the Transcaspian steppe to Northeastern Asia (Manchuria).[1] According to Yunusbayev et al. (2015), genetic evidence points to an origin in the region near South Siberia and Mongolia as the "Inner Asian Homeland" of the Turkic ethnicity.[2] Similarly several linguists, including Juha Janhunen, Roger Blench and Matthew Spriggs, suggest that Mongolia is the homeland of the early Turkic language.[3]

According to Robbeets, the Turkic people descend from people who lived in a region extending from present-day South Siberia and Mongolia to the West Liao River Basin (modern Manchuria).[4]

Authors Joo-Yup Lee and Shuntu Kuang analyzed 10 years of genetic research on Turkic people and compiled scholarly information about Turkic origins, and said that the early and medieval Turks were a heterogeneous group and that the Turkification of Eurasia was a result of language diffusion, not a migration of homogeneous population.[5]

Identity of the Xiongnu (3rd c. BCE - 1st c. CE)

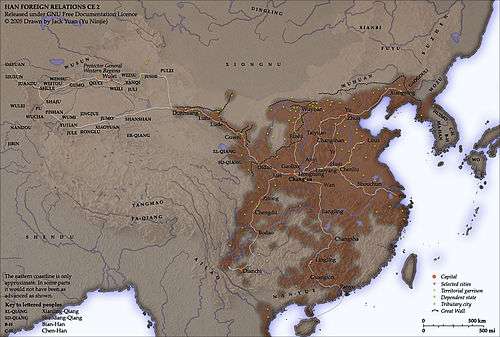

The Xiongnu, appear as nomadic tribes on the plains of the Far East north of the Great Wall of China, which was constructed as a fortified border during essentially Han dynasty China (206 BCE-220 CE) (though started earlier) and the Xiongnu. They lived in Mongolia or along the upper Yenisei in Siberia (the area of the contemporary Tuvan language), and are known from historical sources. The Han chronicle of the Xiongnu, included in the Records of the Grand Historian of the second century BCE, traces a legendary history of them back a thousand years before the Han to a legendary ancestor, Chunwei, a supposed descendant of the Chinese rulers of the Xia dynasty[6] (c. 2070 – c. 1600 BCE). Chunwei lived among the "Mountain Barbarians" Xianyun or Hunzhu. Xianyun and Hunzhu's names may connect them to the Turkic people, who later were said to have been iron-workers and to have kept a national shrine in a mountain cave in Mongolia.

The Xiongnu were a tribal confederation[7] of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources, inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BCE to the late 1st century CE. Chinese sources report that Modu Chanyu, the supreme leader after 209 BC, founded the Xiongnu Empire.[8] Apparently the Xiongnu comprised a number of tribes and geographic groups, not all of which were probably Turkic (considering the later mixed ethnicity). The Records of the Grand Historian mention the Mianshu, Hunrong and Diyuan west of Long; the Yiqu, Dali, Wiezhi and Quyan north of the Qi and Liang mountains and Jing and Qi Rivers; the Forest Barbarians and Loufan north of Jin and the Eastern Barbarians and Mountain Barbarians north of Yan. Later the treatise mentions others.

There were apparently many of the latter. At the end of the Xia, about 1569 BCE by the reckoning of the Records of the Grand Historian, the Chinese founded a city, Bin, among the Rong tribe of barbarians. In 1269 the Rong and the Di forced the relocation of Bin. About 1169 BCE the Quanyishi tribe was attacked by the Zhou Dynasty, which in 1159 forced all the barbarians into "the submissive wastes" north of the Jing and Luo Rivers. In 969 BCE "King Mu attacked the Quanrong and brought back with him four white wolves and four white deer ...." The early Turkic peoples believed that shamans could shape-shift into wolves.

In 769 Marquis Shen of the Zhou enlisted the assistance of the Quanrong in rebelling against the emperor You. The barbarians did not then withdraw but took Jiaohuo between the Jing and Wei Rivers and from there went marauding into central China, but were driven out. In 704 the Mountain Barbarians marauded through Yan, and in 660 BC attacked the Zhou emperor Xiang in Luo. He had discarded a barbarian queen. The barbarians put another on the throne. They went on plundering until driven out in 656 BC.

Subsequently the Chinese drove out the Di and subordinated all the Xiongnu (temporarily at least). Around 456 BC the Chinese took Dai from them. The Yiqu tribe tried building fortifications but lost them to the Chinese in this period of their expansion. Here the detail of the narrative increases as it deals with the rise of the Qin Dynasty of 221-206 BCE, which is no doubt mainly historical rather than legendary. The Qin kept the Xiongnu at bay.

Qin's campaign against the Xiongnu of 215 BCE kept the Xiongnu at bay,[9] driving them out of and seizing the Ordos region.[10] Problems re-emerged after the Qin Dynasty. The Xiong-nu attacked Shanxi of the Han in 201 BCE. Emperor Gaozu of Han bought them off with jade, silk and a Chinese wife for the Shanyu, or leader.[11] Relations with the Xiongnu continued to be troubled and in 133 BC Emperor Wu of Han proceeded against them with 300,000 men.[12] Eighty-one years and fourteen expeditions later in 52 BC the southern Xiongnu surrendered and the northern desisted from raiding. The Han Dynasty military expeditions continued near the frontier of China, in the Han–Xiongnu War, and in 89 AD the Xiongnu state was defeated and soon ended.[13][14]

Attempts to identify the Xiongnu with later groups of the western Eurasian Steppe remain controversial. Scythians and Sarmatians were concurrently to the west. The identity of the ethnic core of Xiongnu has been a subject of varied hypotheses, because only a few words, mainly titles and personal names, were preserved in the Chinese sources. The name Xiongnu may be cognate with that of the Huns or the Huna,[15] although this is disputed.[16][17] Other linguistic links – all of them also controversial – proposed by scholars include Iranian,[18][19][20] Mongolic,[21] Turkic,[22][23] Uralic,[24] Yeniseian,[16][25][26] Tibeto-Burman[27] or multi-ethnic.[28]

Five Hu

The early-fourth-century saw a rebellion, with sacking of northern Chinese cities, by the Xiong-nu. However, most of the Xiongnu were later wiped out by the Chinese Ran Wei state (350–352) after Ran Min's cull order following the end of the Wei–Jie war, which annihilated three of the "Five Hu" tribes. In that century some of the Xiong-nu broke away and joined with the Di as the Five Hu, or "Five Barbarian Peoples" (Wu Hu 五胡), as the Chinese called them, for purposes of ruling the north of China.[29] The Five Hu were the Xiongnu, Jie, Xianbei, Di, and Qiang,[30][31] although different groups of historians and historiographers have their own definitions.

Identity of the Huns (4th-6th c. CE)

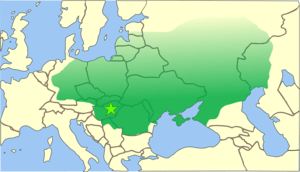

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe, between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part of Scythia at the time; the Huns' arrival is associated with the migration westward of an Indo-Iranian people, the Alans.[32] By 370 AD, the Huns had arrived on the Volga, and by 430 the Huns had established a vast, if short-lived, dominion in Europe, conquering the Goths and many other Germanic peoples living outside of Roman borders, and causing many others to flee into Roman territory.

The actual identity of the Huns is still debated. Concerning the cultural genesis of the Huns, the Cambridge Ancient History of China asserts: "Beginning in about the eighth century BC, throughout inner Asia horse-riding pastoral communities appeared, giving origin to warrior societies." These were part of a larger belt of "equestrian pastoral peoples" stretching from the Black Sea to Mongolia, and known to the Greeks as the Scythians.[33]

The Scythians in the west were Iranian, speaking one among very many languages ultimately descended from Proto-Indo-European, whose speakers themselves are also hypothesised to have occupied the Pontic-Caspian Steppe, according to the leading theory of Indo-European origins, the Kurgan model. The communities of the northern belt north of China, a historically Inner Mongolia region were the Proto-Xiongnu. The Huns have often been considered a Turkic people, and sometimes associated with the Xiongnu. While in Europe, the Huns incorporated others, such as Goths, Slavs, and Alans.

One especially severe round of nomadic rebellion in the early 4th century has led to the certain identification of the Xiongnu with the Huns. A letter (Letter II) written in the ancient Sogdian language excavated from a Han Dynasty watchtower in 1911 identified the perpetrators of these events as the xwn, "Huns", supporting de Guignes' 1758 identification. The equivalence was not without its critics, notably Otto J. Maenchen-Helfen, who argued that xwn was a general name and could refer to anyone. More recently other evidence was noticed: Zhu Fahu, a monk, translated Sanskrit Hūṇa in the Tathāgataguhya Sūtra and in the Lalitavistara Sūtra as "Xiongnu". Vaissière reconstructs the pronunciation as *Xiwong nuo. Moreover, the Book of Wei states that the king of the Xiongnu killed the king of Sogdia and took the country, an event datable to the time of the Huns, who did exactly that; in short, "... the name of the Huns is a precise referent and not generic."[34]

Orosius has the Huns riding down upon the Ostrogoths in the year AD 377 totally by surprise, "long shut off by inaccessible mountains"[35] and apparently of hitherto unsuspected existence. Whatever may have been his reasons for making such a statement, he and Goths might have found ample reference to the Huns in the classical geographers, such as Pliny and Ptolemy; in fact, some were already in Europe.[36] The mountains were mythical as the Ostrogoths were located on the Pontic steppe, an easy target for Hunnic cavalry.

The Huns were not literate (according to Procopius[37]) and left nothing linguistic with which to identify them except their names,[37] which derive from Germanic, Iranian, Turkic, unknown and a mixture.[38] Some, such as Ultinčur and Alpilčur, are like Turkish names ending in -čor, Pecheneg names in -tzour and Kirghiz names in -čoro. Names ending in -gur, such as Utigur and Onogur, and -gir, such as Ultingir, are like Turkish names of the same endings.

One tribe of the Huns called themselves the Acatir (Greek Akatiroi, Latin Acatiri), which Wilhelm Tomaschek derived from Agac-ari, "forest men",[39] reminiscent of the "Forest Barbarians" of the Shi-Ji. The Agaj-eri are mentioned in an AD 1245 Turko-Arabian Dictionary. The name Agac-eri occurred in later history in Anatolia and Khuzistan (e.g. city of Aghajari). Maenchen-Helfen rejects this etymology on the grounds that g is not k and there appears to be no linguistic rule to make the connection.[40] Herodotus, however, mentions the Agathyrsi, whom Latham connects with some early Acatiri in Dacia.[41]

Jordanes places the "most mighty race of the Acatziri, ignorant of agriculture, which lives upon its herds and upon hunting" south of the Aesti (in part Prussians). A number of sources identify the Bulgars with the Huns.[42] Another branch were the Saviri, or Sabir people. The strongest candidate for a remnant of the speakers of the Hunnic language are the Chuvash, who are on or near the location of the Volga Bulgars.

The end of the Huns as a Eurasian political unity is not known. A token end point for the Huns of the west, perhaps all the Huns, is the fixation of the head of Dengizich, a son of Attila, on a pole at Constantinople in 469. He had been defeated in Thrace in that year by Anagastes, a Gothic general in the service of the Roman Empire.[43]

Various peoples continued to call themselves Huns even though acting autonomously, such as the Sabir people. According to the Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, the last state to call itself Hunnic was the Caucasian Kingdom of the Huns, visited in 682 by an Albanian bishop.[44] Many of these peoples were Turkic but meanwhile other coalitions leading to explicitly named Turkic empires had been forming on the original range of the Xiong-nu. Their expansion has been conventionally called the "Turkic migration" but in fact the Turkics had already been "migrating" for some centuries.

Göktürks (5th-8th c.)

The term Türk or Türküt, transcribed in Chinese as 突厥 Tūjué, was first used as an endonym in the Orkhon inscriptions of the Göktürks (English: 'Celestial Turks') of Central Asia. The first reference to "Turks" appears in Chinese sources of the 6th century. The earliest evidence of Turkic languages as a separate group comes from the Orkhon inscriptions of the early 8th century. However, the Chinese transcription 鐵勒 Tiělè, for underlying endonym *Tegreg "[People of the] Carts"[45], was used much earlier, to denote a confederation of Turkic-speakers distinct from yet related to Tujue, around the period when the Mongolic tribes Tuoba and Rouran vied for hegemony over the Mongolian steppes around the 5th and 6th centuries.

The precise date of the initial expansion from the early homeland remains unknown. The first state known as "Turk", giving its name to the many states and peoples afterwards, was that of the Göktürks (gök = 'blue' or 'celestial', however in this context "gök" refers to the direction "east". Therefore, Gokturks are the Eastern Turks) in the 6th century. The head of the Ashina clan led his people from Li-jien (modern Zhelaizhai) to the Rouran seeking inclusion in their confederacy and protection from China. His tribe comprised famed metal smiths and was granted land near a mountain quarry that looked like a helmet, from which they got their name 突厥. A century later their power had increased such that Turks, led by the Ashina tribe, revolted against Rouran overlords and set about establishing First Turkic Khaganate.[46]

The Turkic family of languages were spoken by Bulgars, Gaoche peoples long before the Göktürk Khanate came into prominence. Many groups speaking 'Turkic' languages never adopted the name "Turk" for their own identity. Among the peoples that came under Göktürk dominance and adopted its political culture and lingua-franca, the name "Turk" wasn't always the preferred identity. In other words, there wasn't a unified movement westward by a culture under one unified ethnic identity, such as that of the Mongol conquest of Eurasia under the Chinggisid political leadership. Rather, Turkic languages – both peripheral ones like the Bulgar branch and central ones like the Oghuz and Karluk-Chagatai branches – drifted westward by autonomous movements of diverse tribes and migrating traders, soldiers and townspeople, outnumbering and assimilating non-Turkic indigenous peoples along the way, and being partly replaced by other language families that have become prominent in the east, such as Mongolic languages on the Mongolian steppes, Indo-Aryan languages in the Indian subcontinent, and Persian in the Central Iranian Plateau.[47]

Later Turkic peoples

_eng.png)

Later Turkic peoples include the Khazars, Turkmens: either Karluks (mainly 8th century) or Oghuz Turks, Uyghurs, Yenisei Kyrgyz, Pechenegs, Cumans-Kipchaks, etc. As these peoples were founding states in the area between Mongolia and Transoxiana, they came into contact with Muslims, and most gradually adopted Islam. However, there were also some other groups of Turkic people who belonged to other religions, including Christians, Judaists, Buddhists, Manichaeans, and Zoroastrians.

Turkmens

While the Karakhanid state remained in this territory until its conquest by Genghis Khan, the Turkmen group of tribes was formed around the core of westward Oghuz. The name "Turkmen" originally simply meant "I am Turk" in the language of the diverse tribes living between the Karakhanid and Samanid states. Thus, the ethnic consciousness among some, but not all Turkic tribes as "Turkmens" in the Islamic era came long after the fall of the non-Muslim Gokturk (and Eastern and Western) Khanates. The name "Turk" in the Islamic era became an identity that grouped Islamized Turkic tribes in contradistinction to Turkic tribes that were not Muslim (that mostly have been referred to as "Tatar"), such as the Nestorian Naiman (which became a major founding stock for the Muslim Kazakh nation) and Buddhist Tuvans. Thus the ethnonym "Turk" for the diverse Islamized Turkic tribes somehow served the same function as the name "Tajik" did for the diverse Iranian peoples who converted to Islam and adopted Persian as their lingua-franca. Both names first and foremost labeled Muslimness, and to a lesser extent, common language and ethnic culture. Long after the departure of the Turkmens from Transoxiana towards the Karakum and Caucasus, consciousness associated with the name "Turk" still remained, as Chagatay and Timurid period Central Asia was called "Turkestan" and the Chagatay language called "Turki", even though the people only referred to themselves as "Mughals", "Sarts", "Taranchis" and "Tajiks". This name "Turk", was not commonly used by most groups of the Kypchak branch, such as the Kazakhs, although they are closely related to the Oghuz (Turkmens) and Karluks (Karakhanids, Sarts, Uyghurs). Neither did Bulgars (Kazan Tatars, Chuvash) and non-Muslim Turkic groups (Tuvans, Yakuts, Yugurs) come close to adopting the ethnonym "Turk" in its Islamic Era sense. Among the Karakhanid period Turkmen tribes rose the Atabeg Seljuq of the Kinik tribe, whose dynasty grew into a great Islamic empire stretching from India to Anatolia.

Turkic soldiers in the army of the Abbasid caliphs emerged as the de facto rulers of much of the Muslim Middle East (apart from Syria and North Africa) from the 13th century. The Oghuz and other tribes captured and dominated various countries under the leadership of the Seljuk dynasty, and eventually captured the territories of the Abbasid dynasty and the Byzantine Empire.

Meanwhile, the Kyrgyz and Uyghurs were struggling with one another and with the Chinese Empire. The Kyrgyz people ultimately settled in the region now referred to as Kyrgyzstan. The Batu hordes conquered the Volga Bulgars in what is today Tatarstan and Kypchaks in what is now Southern Russia, following the westward sweep of the Mongols in the 13th century. Other Bulgars settled in Europe in the 7-8th centuries, but were assimilated by the Slavs, giving the name to the Bulgarians and the Slavic Bulgarian language.

It was under Seljuq suzerainty that numerous Turkmen tribes, especially those that came through the Caucasus via Azerbaijan, acquired fiefdoms (beyliks) in newly conquered areas of Anatolia, Iraq and even the Levant. Thus, the ancestors of the founding stock of the modern Turkish nation were most closely related to the Oghuz Turkmen groups that settled in the Caucasus and later became the Azerbaijani nation.

By early modern times, the name "Turkestan" has several definitions:

- land of sedentary Turkic-speaking townspeople that have been subjects of the Central Asian Chagatayids, i.e. Sarts, Central Asian Mughals, Central Asian Timurids, Taranchi of Chinese Turkestan, and the later invading East Kipchak Tatars who mixed with local Sarts and Chagatais to form the Uzbeks; This area roughly coincides with "Khorasan" in the widest sense, plus Tarim Basin which was known as Chinese Turkestan. It is ethnically diverse, and includes homelands of non-Turkic peoples like the Tajiks, Pashtuns, Hazaras, Dungans, Dzungars. Turkic peoples of the Kypchak branch, i.e. Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, are not normally considered "Turkestanis" but are also populous (as pastoralists) in many parts of Turkestan.

- a specific district governed by a 17th-century Kazakh Khan, in modern-day Kazakhstan, which were more sedentary than other Kazakh areas, and were populated by towns-dwelling Sarts

See also

References

Citations

- Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg (2015-04-21). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLoS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

The origin and early dispersal history of the Turkic peoples is disputed, with candidates for their ancient homeland ranging from the Transcaspian steppe to Manchuria in Northeast Asia,

- Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg (2015-04-21). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLoS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

Thus, our study provides the first genetic evidence supporting one of the previously hypothesized IAHs to be near Mongolia and South Siberia.

- Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (2003-09-02). Archaeology and Language II: Archaeological Data and Linguistic Hypotheses. Routledge. ISBN 9781134828692.

- "(PDF) Transeurasian theory: A case of farming/language dispersal". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2019-03-13.

- Lee (18 Oct 2017). Brill. 19 (2) https://brill.com/view/journals/inas/19/2/article-p197_197.xml. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Sima, Qian; Burton Watson (1993). Records of the Grand Historian. Columbia University Press. pp. 129–162. ISBN 978-0-231-08166-5.

- "Xiongnu People". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- di Cosmo 2004: 186

- Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road: Two Thousand years in the Heart of Asia. University of California Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-520-23786-5.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2009). East Asia: A cultural, social, and political history (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-547-00534-8.

- Morton, W. Scott; Charlton M. Lewis (2004). China: Its History and Culture: Fourth Edition. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-07-141279-7.

- Morton (2004), page 55.

- Book of Later Han, vols. 04, 19, 23, 88, 89, 90.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 47.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 19, 26–27. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Beckwith 2009, pp. 51–52, 404–405

- Vaissière 2006

- Harmatta 1994, p. 488: "Their royal tribes and kings (shan-yii) bore Iranian names and all the Hsiung-nu words noted by the Chinese can be explained from an Iranian language of Saka type. It is therefore clear that the majority of Hsiung-nu tribes spoke an Eastern Iranian language."

- Bailey 1985, pp. 21–45

- Jankowski 2006, pp. 26–27

- Tumen D., "Anthropology of Archaeological Populations from Northeast Asia page 25, 27

- Hucker 1975: 136

- "(PDF) Transeurasian theory: A case of farming/language dispersal". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2019-03-13.

- Di Cosmo, 2004, pg 166

- Adas 2001: 88

- Vovin, Alexander. "Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language?". Central Asiatic Journal 44/1 (2000), pp. 87–104.

- 高晶一, Jingyi Gao (2017). 確定夏國及凱特人的語言為屬於漢語族和葉尼塞語系共同詞源 [Xia and Ket Identified by Sinitic and Yeniseian Shared Etymologies]. Central Asiatic Journal. 60 (1–2): 51–58. doi:10.13173/centasiaj.60.1-2.0051. JSTOR 10.13173/centasiaj.60.1-2.0051.

- Geng 2005

- Holcombe, Charles (2001). The Genesis of East Asia, 221 B.C.-A.D. 907. University of Hawaii Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-8248-2465-2.

- "The Sixteen States of the Five Barbarian Peoples 五胡十六國 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- Saso, Michael R. (1991). Buddhist Studies in the People's Republic of China, 1990–1991. University of Hawaii Press. p. 141. ISBN 0-8248-1363-4.

- Sinor 1990, p. 180.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (1999). "The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C. Cambridge University Press. p. 886. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Vaissière, Etienne de la (2004). "The Rise of Sogdian Merchants and the Role of the Huns: The Historical Importance of the Sodgian Ancient Letters". In Whitfield, Susan (ed.). The Silk Road: Trade, travel, War and Faith. Translated by Hampson, Kate. Chicago: Serindia Publications Inc. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-1-932476-12-5.

- Orosius. "Historiarum Adversum Paganos Libri VII". Book VII Section 33.10. The Latin Library.

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto J. (1973). Max Knight (ed.). The World of the Huns. The University of California Press. pp. 444–455.

- Maenchen-Helfen (1973) page 376.

- Maenchen-Helfen (1973) pages 441–442.

- Maenchen-Helfen (1973) pages 427–428.

- Maenchen-Helfen (1973) page 437.

- Latham, Robert Gordon (2003). The Nationalities of Europe: Volume 2. Adamant Media Corporation. p. 391. ISBN 1-4021-8765-3.

- Maenchen-Helfen (1973) page 432.

- Maenchen-Helfen (1973), Page 168.

- Sinor, Denis (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 201. ISBN 0-521-24304-1.

- Ḡozz at Encyclopædia Iranica

- Gao Yang, "The Origin of the Turks and the Turkish Khanate", X. Türk Tarih Kongresi: Ankara 22 – 26 Eylül 1986, Kongreye Sunulan Bildiriler, V. Cilt, Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1991, s. 731. (in English)

- Borjian, Habib. "Median succumbs to Persian after three millennia of coexistence: Language shift in the Central Iranian Plateau." Journal of Persianate Studies 2.1 (2009): 62-87.

Sources

- Findley, Carter Vaughnm, The Turks in World History, Oxford University Press: Oxford (2005).

- Holster, Charles Warren, The Turks of Central Asia Praeger: Westport, Connecticut (1993).

- Sinor, Denis (1990). "The Hun Period". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Cambridge history of early Inner Asi a (1st. publ. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 177–203. ISBN 9780521243049.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)