Turkish occupation of northern Syria

The Turkish Armed Forces and its ally the Syrian National Army have controlled[12][13] areas of northern Syria since August 2016, during the Syrian Civil War. Though these areas nominally acknowledge a government affiliated with the Syrian opposition, they factually constitute a separate proto-state[14] under the dual authority of decentralized native local councils and Turkish military administration.

Northern Syria Security Belt | |

|---|---|

| |

.svg.png) | |

| Capital | Azaz[4] |

| Largest city | Azaz[5] |

| Official languages | |

| Government | Provisional Government (dual authority of decentralized local councils and military administration) |

• President | Anas al-Abdah |

• Prime Minister | Abdurrahman Mustafa |

• Minister of Defence | Salim Idris |

| Self-governance under military occupation | |

| 24 August 2016 | |

| 20 January 2018 | |

| 9 October 2019 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 8,835[7][8][9] km2 (3,411 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 2,480,000[10][11] |

| Currency | Syrian pound, Turkish lira,[2] United States dollar |

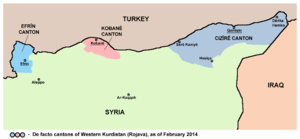

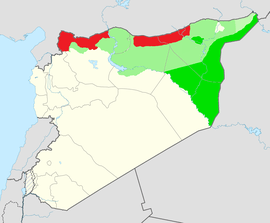

Turkish-controlled areas of Syria consists of a 8,835-square-kilometre area which encompasses over 1000 settlements, including towns such as Afrin, al-Bab, Azaz, Jarabulus, Jindires, Rajo, Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ayn. The majority of these settlements had been captured from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), both of which have been designated as terrorist organisations by the Turkish government, although some towns, including Azaz, were under the control of the Syrian opposition before Turkish intervention. The Syrian Interim Government moved into the Turkish-controlled territories and began to extend partial authority there, including providing documents to Syrian citizens. These areas are referred to as "safe zones" (Turkish: Güvenli Bölge) by Turkish authorities.[15][16][17][18][19]

Background

2013–14 proposals for Safe Zone

Turkey and Syrian opposition proposed a safe zone that includes some regions of northern Syria in 2013, however United States and the other Western states were not willing to accept these plans.[20][21] After the advancements of ISIL in Iraq, Turkey and United States negotiated 'safe zone', while USA accepted 'ISIL-free zone', US officials were reluctant to accept a no fly zone.[22][23]

European support

After the attacks of ISIL in Syria, tens of thousands non-Sunnis, Christians and Yazidis fled to Turkey. In the beginning of 2015, refugees began to cross the Greece–Turkey border, escaping to European countries in massive numbers. The huge refugee flow resulted in reconsidering the creation of a safe zone for civilians in Syria.[24] In February 2016, Chancellor of Germany Angela Merkel said, "In the current situation it would be helpful if there could be such an area where none of the parties are allowed to launch aerial attacks – that is to say, a kind of no-fly zone".[25]

U.S.-Turkish negotiations

The creation of the safe zone failed in early 2016 due to disagreements between the United States and Turkish governments, primarily on which actor is to be eliminated first. While Turkey wanted the Syrian government to be overthrown as soon as possible, the US prioritised the war against ISIL. The US also feared that the Syrian Air Force would bomb the area, which would make the idea of a safe zone impracticable. The government rejected the safe zone for being a safe haven for both civilians and rebels.

The outline of the safe zone was another reason for the disagreement. According to Turkey, the safe zone should include a no fly zone, whereas the US rejected establishing a no-fly zone, which would bring a conflict with the Syrian government.[26]

Turkey designates the Kurdish YPG to be a threat, due to its strong ties with the PKK. On the other hand, the US said that although they deem the PKK as a terrorist organisation, the YPG is a distinct actor, constituting one of the main allies of the US in its war against ISIL.[27]

Another debate was about the name of the safe zone. While Turkey called the zone a 'safe zone from ISIS, the Syrian regime and YPG,' the US, however, declared that they will only accept an 'ISIS-free zone'.[28]

On October 7, 2019, the President of the United States ordered the withdrawal of US military troops stationed on the Syria–Turkey border. This withdrawal of military support was ordered by the President with the disapproval of the Pentagon and the US Intelligence community. The US President ordered the withdrawal of military troops under the premise that Turkey would not invade the region being held by Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF); however Turkey attacked the SDF within 24 hours of US military withdrawal from the region.

Geography

The territory of the Turkish-controlled region is entirely located within the northern areas of the Aleppo Governorate, with the southern tip of the territory located 40 kilometres northeast of Aleppo. On 26 February 2018, the territory connected with the mostly rebel-held Idlib Governorate.[29]

The Syrian National Army captured an area of 2,225-square-kilometres during Operation Euphrates Shield.[30] Areas captured during the operation included villages between Azaz and al-Rai, such as Kafr Kalbin; Kafrah; Sawran; Ihtaimlat; Dabiq; Turkman Bareh; Kafr Elward; Ghoz; Ghaytun; Akhtarin; Baruza; Tall Tanah; Kaljibrin; Qebbet al-Turkmen; Ghandoura; Arab Hassan Sabghir; Mahsenli; Qabasin and Halwanji.

Following Operation Olive Branch, Syrian National Army extended the region with the capture of the entire Afrin District.[31] In addition to its administrative centre Afrin, the district includes settlements such as Bulbul, Maabatli, Rajo, Jindires, Sharran and Shaykh al-Hadid. According to the 2004 Syrian census, the district had a population of 172,095 before the war.[32]

During Operation Peace Spring, Turkish Armed Forces and its allies captured a total area of between 3,412 square kilometres (1,317 sq mi)[33] and 4,220 square kilometres (1,630 sq mi),[34] and 68 settlements, including Ras al-Ayn, Tell Abyad, Suluk, Mabrouka and Manajir and cut the M4 highway.[35][35][36][37] SNA forces captured 3 villages in the Manbij countryside shortly after the launch of the operation.[38]

There are further intentions by the Turkish government to include the areas captured by the Syrian Democratic Forces during their offensive west of the Euphrates into the safe zone, which includes settlements such as Manbij and Arima.[39][40]

Demographics

The Turkish-controlled region is ethnically diverse, inhabited predominately by Turkmens, Arabs, Kurds and Yazidis, with Circassian minorities near Azaz.[41] More than 200,000 people fled from Afrin District during the Turkish intervention by March 2018.[42] While 458,000 displaced persons from other parts of Syria settled in Afrin following the Turkish intervention.[43]

Population centres

This list includes all cities and towns in the region with more than 50,000 inhabitants. The population figures are given according to 2018 and 2020 estimates.[43][5][11]

| English Name | Arabic Name | Kurdish Name | Turkish Name | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azaz | أعزاز | – | Azez | 194,467 |

| Afrin | عفرين | Efrîn | Afrin | 163,300 |

| Jarabulus | جرابلس | Cerablûs | Cerablus | 120,040 |

| Akhtarin | أخترين | – | Aktarin | 117,916 |

| Tell Abyad | تل أبيض | Girê Spî | Tellebyad | 100,000 |

| al-Bab | الباب | – | El-Bab | 99,790 |

| Ras al-Ayn | رأس العين | Serê Kaniyê | Resulayn | 80,000 |

| Sawran | صوران | – | Soran | 65,477 |

| Bizaah | بزاعة | – | Bizza | 52,552 |

| Qabasin | قباسين | Qebasîn | Başköy | 50,795 |

| Mare' | مارع | – | Mare | 50,331 |

Politics and administration

The occupation zone is formally governed by the Syrian Interim Government, an alternative government of the Syrian opposition based in Azaz.[4] Despite this, the area is governed by a number of autonomous local councils which work closely with Turkey.[44][45] In general, Turkey exerts a direct influence on the region's government,[46] and Turkish civilian officials such as governors have been appointed to oversee the area.[47] Accordingly, Turkey is in the process of forming a proto-state in northern Syria,[14] and regional expert Joshua Landis has said that the country "is prepared to, in a sense, quasi-annex this region" to prevent it from being retaken by the Syrian government.[1] Turkish Minister of the Interior Süleyman Soylu declared in January 2019 that northern Syria is "part of the Turkish homeland" per the Misak-ı Millî of 1920.[47]

Since the establishment of the zone, the Turkish authorities have striven to restore civil society in the areas under their control[48] and to also bind the region more closely to Turkey.[6][2][49] As part of these efforts, towns and villages have been demilitarized by dismantling military checkpoints and moving the local militias to barracks and camps outside areas populated by civilians.[48] Turkey also funds education and health services, supports the region's economy, and has trained a new police force.[2][49] Some locals describe these developments as "Turkification" of the region. However, many locals have accepted or even welcomed this, as they said that the area is better off economically, politically, and socially under a Turkish protectorate.[1] The White Helmets volunteers entered Afrin region after Turkey occupied the area.[50]

Local government

Local councils form the primary government of the zone, and operate largely autonomous.[44]

Following the conquest of Afrin District, civilian councils were formed to govern and rebuild the area. A first temporary council was organised by the Turkish-backed Syrian Kurds Independent Association in March 2018 to oversee aid, education and media in the area.[51] It was later replaced by an interim council that was established in Afrin city on 12 April.[52][53] The latter council, appointed by city elders, included eleven Kurds, eight Arabs and one Turkmen. Zuheyr Haydar, a Kurdish representative who was appointed to serve as president of the council, stated that a more democratic election would take place if displaced citizens return. PYD officials have criticized the council and said it was working with an “occupying force”.[54] On 19 April, a local council was established in Jindires.[55] During Operation Peace Spring, local councils have been established in Tel Abyad[56] and Ras al-Ayn.[57]

Ethnic cleansing

After the Turkish-led forces had captured Afrin District (Afrin Canton) in early 2018, they began to implement a resettlement policy by moving their mostly Arab fighters[58] and refugees from southern Syria[59] into the empty homes that belonged to displaced locals.[60] The previous owners, most of them Kurds or Yazidis, were often prevented from returning to Afrin.[58][59] Though some Kurdish militias of the SNA and the Turkish-backed civilian councils opposed these resettlement policies, most SNA units fully supported them.[59] Refugees from Eastern Ghouta, Damascus, said that they were part of "an organised demographic change" which was said to replace the Kurdish population of Afrin with an Arab majority.[58]

Military

.jpg)

On 30 May 2017,[61] the Syrian National Army composed of Syrian Arab and Syrian Turkmen rebels operating in northern Syria was formed, mostly being a part of Operation Euphrates Shield or groups active in the area that are allied to the groups participating in the operation.[62][63] The general aim of the group is to assist Turkey in creating a "safe zone" in Syria and to establish a National Army, which will operate in the land gained as a result of Turkish military intervention[64] and answer to the Syrian Interim Government.[48]

By August 2018, the SNA was stated to be an "organized military bloc" that had largely overcome the chronic factionalism which had traditionally affected the Syrian rebels. Military colleges had been set up, and training as well as discipline had been improved.[49] Though clashes and inter-unit violence still happened,[45][14] they were no longer as serious as in the past. A military court had been established in al-Bab, a military police was organized to oversee discipline,[49][14] and local civilian authorities were given more power over the militant groups. Nevertheless, most militias have attempted to maintain their autonomy to some degree, with the Interim Government having little actual control over them. To achieve the formation of a new national army without risking a mutiny, Turkey has applied soft pressure on the different groups while punishing only the most independent-minded and disloyal among them.[14] The FSA units in the zone have accepted the Istanbul-based "Syrian Islamic Council" as religious authority.[48] SNA fighters are paid salaries by the Turkish government, though the falling value of Turkish lira began to cause resentment among the SNA by mid-2018. One fighter said that "when the Turkish lira began to lose value against the Syrian pound our salaries became worthless".[2]

By July 2018, the Turkish Armed Forces (TAF) have built "at least" six military bases in the zone, "raising concerns that [the TAF] may be settling in for a long-term presence in northern Syria".[46]

Law enforcement

Turkey has organized a new law enforcement authority in the zone in early 2017, the "Free Police" which is divided into the National Police and Public Security Forces. The Free Police includes both male as well as female officers.[65] It is trained, equipped, and paid by Turkish authorities,[65] and consequently loyal to the Turkish state.[66][67]

The National Police, headed by Maj. Gen. Abdul Razzaq Aslan, is further divided into the Civil Police Force and the Special Forces. Most of the police members are trained in the Turkish National Police Academy.[49] To maintain security in Afrin District, Turkey has also employed former members of the Free East Ghouta Police who had relocated to northern Syria after the end of the Siege of Eastern Ghouta.[68]

Economy

By July 2018, Turkey was playing an "increasingly prominent—and contentious—role in the region's local economy."[46] It invested heavily in the zone, providing work opportunities and helping to rebuild the economy. Turkish-led development projects restored infrastructure such as dams, electricity and roads.[49] Turkish private companies, such as PTT,[6] Türk Telekom, the Independent Industrialists and Businessmen Association, and ET Energy launched projects in the area, as did a number of Syrian firms and businessmen.[49] One problematic result of Turkey's economic influence was that the country's currency and debt crisis has also affected the zone, as Turkey pays salaries and services with Turkish lira whose value greatly dropped in course of 2018, harming the local economy.[2][49]

Tourism

As result of the Turkish-led invasion, Afrin's tourism sector which had survived the civil war up to that point, collapsed. After open combat between the SDF and pro-Turkish forces had mostly concluded, Turkey attempted to restablize the region and to revive the local tourism. It removed the tight control over visitors and passers that had previously existed under the PYD-led administration, and the new local councils and the Free Police attempted to provide stability and incentives for tourists to return. By July 2018, these measures began to have an effect, with some visitors coming to Afrin's popular recreational areas, such as Maydanki Lake.[69]

Education

Turkey has taken "full control over the educational process" in the zone,[49] and funds all education services.[2] Several schools have been restored or newly built, with their curricula partially adjusted to education in Turkey: Though the curricula of the Syrian Ministry of Education still provide the basis, certain parts have been modified to fit the Turkish point of view in regard to history, for example replacing "Ottoman occupation" with "Ottoman rule".[49] Turkish is taught as foreign language since first class and those who attend schools in the occupation zones can subsequently attend universities in Turkey.[6][1][49]

Reactions

Reactions within Syria

The Syrian government under Bashar al-Assad has repeatedly criticized Turkish presence in Northern Syria[70][71] and called for their withdrawal.[72][73][74][75]

- Democratic Conservative Party – The Democratic Conservative Party condemned the occupation, stating that Turkey was attempting to annex Afrin.[79]

International reaction

See also

References

- Madeline Edwards (6 August 2018). "As Syria's proxies converge on Idlib, what's next for Turkey's northern state-within-a-state?". SYRIA:direct and Konrad Adenauer Foundation. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Khalil Ashawi (28 August 2018). "Falling lira hits Syrian enclave backed by Turkey". Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ANF (29 March 2019). "ID cards of civilians replaced with Turkish ID cards in Afrin". Ajansa Nûçeyan a Firatê. ANF News. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "Turkey's Idlib Incursion and the HTS Question: Understanding the Long Game in Syria". War on the Rocks. October 31, 2017. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- "Fırat Kalkanı Bölgesinde Demografik Sayılar". Suriye Gündemi. 7 February 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Sydow, Christoph (14 October 2017). "Syrien: Willkommen in der türkischen Besatzungszone" [Syria: Welcome to the Turkish occupation zone]. Spiegel Online. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- "30 يوما من نبع السلام: "قسد" تخسر نصف مساحة سيطرتها تقريبا.. وروسيا و"النظام" لاعب جديد في الشمال السوري.. وانتهاكات الفصائل التركية تجبر المدنيين على الفرار.. وأكثر من 870 شهيداً وقتيلاً.. وأوضاع إنسانية وصحية كارثية تهدد المنطقة". Archived from the original on 2019-11-09. Retrieved 2019-11-09.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-11-09. Retrieved 2019-11-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-11-09. Retrieved 2019-11-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Fırat Kalkanı ve Zeytin Dalı Harekatları Bölgelerinde Nüfus Artışı". Suriye Gündemi. 21 March 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Vali Erin: Telabyad ve Resulayn'ın nüfusu 180 binin üzerinde". Habertürk. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Sirwan Kajjo (2 March 2017). "Skirmishes Mar Fight Against IS in Northern Syria". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

Turkish occupation “is an existential threat to the Assad government's ability to reclaim the entirety of its territory, which is a key argument that regime loyalists make in their support of Bashar al-Assad's government,” Heras said.

- Robert Fisk (29 March 2017). "In northern Syria, defeated Isis fighters leave behind only scorched earth, trenches – and a crucifixion stand". The Independent. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

You can’t mistake the front line between the Syrian army and Turkey’s occupation force east of Aleppo.

- Haid Haid (2 November 2018). "Turkey's Gradual Efforts to Professionalize Syrian Allies". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "Safe zone 'crucial for Turkmen in Syria'". www.aa.com.tr. Archived from the original on 2019-10-07. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- "Has the International Community Succeeded in Creating a Safe Zone in Syria After Years of War?". April 17, 2017. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- Macaron, Joe. "Trump's 'real estate' approach to safe zones in Syria". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-24. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- "Turkey's troops cross over into Syria's Afrin". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2019-04-28. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-11-07. Retrieved 2019-11-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Turkey PM 'will support' Syria no-fly zone". Archived from the original on 1 August 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- "Syrian opposition calls for no-fly zone". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Tisdall, Simon (27 July 2015). "Syrian safe zone: US relents to Turkish demands after border crisis grows". Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- "DIPLOMACY - US and Turkey agree to forge 'ISIL-free zone' in Syria, official confirms". Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- "Solution to refugee crisis is to end Syria's civil war, UN official says". Archived from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Wintour, Patrick (16 February 2016). "Turkey revives plan for safe zone in Syria to stem flow of refugees". Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- "National Security Zone". Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- "Fight against IS helps PKK gain global legitimacy - Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East". 16 September 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- "U.S. denies reaching agreement with Turkey on Syria 'safe zone'". 11 August 2015. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016 – via Reuters.

- "Turkey reconnects opposition-held areas in northern Syria - Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 2018-09-19. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- "'El Bâb kontrol altına alınmıştır'". Al Jazeera Turk - Ortadoğu, Kafkasya, Balkanlar, Türkiye ve çevresindeki bölgeden son dakika haberleri ve analizler. Archived from the original on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- "Turkey takes full control of Syria's Afrin region, reports say". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 2019-10-14. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- "General Census of Population and Housing 2004" (PDF) (in Arabic). Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015. Also available in English: "2004 Census Data". UN OCHA. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- "The Turkish forces and the factions advance and take control of about 10 villages in Abu Rasin area (Zarkan) amid the continuation of fierce clashes against the regime forces and tens of casualties and wounded in the ranks of the both parties". 29 October 2019. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "YPG/PKK terror group as dangerous as Daesh: Erdogan". Archived from the original on 2019-10-26. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- "8 days of Operation "Peace Spring": Turkey controls 68 areas, "Ras al-Ain" under siege, and 416 dead among the SDF, Turkish forces and Turkish-backed factions". 17 October 2019. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "http://www.syriahr.com/?p=342499". External link in

|title=(help) - "قوات سوريا الديمقراطية تنسحب من كامل مدينة رأس العين (سري كانييه) • المرصد السوري لحقوق الإنسان". 20 October 2019. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "Menbiç'e operasyon başladı: 3 köy YPG'den temizlendi". Yeni Şafak. 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "404 Not Found". www.washingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on 2018-12-03. Retrieved 2017-04-10.

- "Turkey says will take action if militants do not leave Syria's Manbij". March 28, 2018. Archived from the original on October 10, 2019. Retrieved October 10, 2019 – via www.reuters.com.

- Izady, Michael. "Syria: Ethnic Composition (summary)". columbia.edu. University of Columbia. Archived from the original on 23 July 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "More than 200,000 people fled Syria's Afrin, have no shelter: Kurdish official Archived 2018-11-25 at the Wayback Machine". Reuters. 19 March 2018.

- "Afrin: Kurdish population more than halved since 2018 offensive, says rights group". Rudaw. 20 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi (23 August 2018). "In Syria, It's Either Reconciliation or Annexation". The American Spectator. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- Borzou Daragahi (13 July 2018). "Turkey Has Made a Quagmire for Itself in Syria". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Barrett Limoges; Justin Clark; Avery Edelman (29 July 2018). "What's next for post-Islamic State Syria? A month-long reporting series from Syria Direct". Syria Direct, Konrad Adenauer Foundation. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- Rawa Barwari (13 January 2019). "Turkish sub-governor found dead at office in Syria's occupied Jarabulus". Kurdistan24. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- Khaled al-Khateb (12 September 2017). "FSA relocating to outside Syria's liberated areas". al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- Enab Baladi's Investigation Team (29 August 2018). "From Afrin to Jarabulus: A small replica of Turkey in the north". Enab Baladi. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- "White Helmets return to Afrin to mixed reception". Kurdistan 24. 26 August 2018. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Mohammad Abdulssattar Ibrahim; Alice Al Maleh; Tariq Adely (26 March 2018). "Interim governing council formed to tackle 'disaster' in Afrin after Turkish-backed offensive". SYRIA:direct. Archived from the original on 24 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- "Interim local council established in Syria's Afrin". www.aa.com.tr. Archived from the original on 2019-10-10. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- "Interim local council established in Syria's Afrin - World News". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 2018-09-06. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- "Turkey-backed council is to take over Afrin, suspicion abound". Ahval. Archived from the original on 2018-06-16. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

- "Cinderes'te yerel meclis oluşturuldu". Timeturk.com. Archived from the original on 2018-11-18. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-11-05. Retrieved 2019-11-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-11-09. Retrieved 2019-11-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Patrick Cockburn (18 April 2018). "Yazidis who suffered under Isis face forced conversion to Islam amid fresh persecution in Afrin". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 June 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- Ammar Hamou; Barrett Limoges (1 May 2018). "Seizing lands from Afrin's displaced Kurds, Turkish-backed militias offer houses to East Ghouta families". SYRIA:direct. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- "Syria's war of ethnic cleansing: Kurds threatened with beheading by Turkey's allies if they don't convert to extremism". The Independent. 12 March 2018. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- "Turkey-backed opposition to form new army in northern Syria". Archived from the original on 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- "Turkey-backed Free Syrian Army eliminates 'terrorist microbes' along Syrian border". RT. 5 September 2016. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- Kajjo, Sirwan (25 August 2016). "Who are the Turkey backed Syrian Rebels?". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- Coskun, Orhan; Sezer, Seda (19 September 2016). "Turkey-backed rebels could push further south in Syria, Erdogan says". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- Khaled al-Khateb (1 December 2017). "Women join opposition police forces in Aleppo's liberated areas". al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- Stein, Aaron; Abouzahr, Hossam; Komar, Rao (20 July 2017). "How Turkey Is Governing in Northern Aleppo". Syria Deeply. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Amberin Zaman (25 January 2017). "Syria's new national security force pledges loyalty to Turkey". al-Monitor. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- Bahira al-Zarier; Justin Clark; Mohammad Abdulssattar Ibrahim; Ammar Hamou (14 May 2018). "Hidden explosives stunt movement, frighten Afrin residents two months into pro-Turkish rule". SYRIA:direct. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Khaled al-Khateb (26 July 2018). "Day trippers flock to Afrin's orchards as Aleppo restores security". al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-11-02. Retrieved 2019-11-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Elements of pro-government NDF militias. Archived 2019-10-29 at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-11-02. Retrieved 2019-11-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-03-20. Retrieved 2019-11-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-04-07. Retrieved 2019-11-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-11-02. Retrieved 2019-11-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Kurdish-backed council says Turkey's intervention to make Syrian town "grave for Erdoğan troops"". ARA News. 26 August 2016. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-02-23. Retrieved 2018-04-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Syrian Kurds welcome multi-ethnic Afrin local council". www.aa.com.tr. Archived from the original on 2019-07-02. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- "Akram Mahshoush: Partition wall aims to erase Kurdish identity, settle mercenaries". Hawar News Agency. 28 May 2019. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- sitesi, milliyet.com.tr Türkiye'nin lider haber. "AZERBAYCAN MİLLETVEKİLİ PAŞAYEVA:". MİLLİYET HABER – TÜRKİYE'NİN HABER SİTESİ. Archived from the original on 2016-10-21. Retrieved 2016-09-20.

- "Cyprus House condemns Turkey's invasion of Syria". Famagusta Gazette. 9 September 2016. Archived from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- "Iran urges Turkey to quickly end Syria intervention". France24. 31 August 2016. Archived from the original on 31 August 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- "France's Macron Vows Support for Northern Syrians, Kurdish Militia, New York Times, March 30th, 2018". Archived from the original on 2018-03-31. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- "Turkey Started Preparations for Further Operations in Northern Syria: Erdoğan, New York Times, March 30th, 2018". Archived from the original on 2018-03-31. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

.jpg)