Kyrgyz in China

The Kyrgyz are a Turkic ethnic group and form one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by the People's Republic of China. There are 202,500 Kyrgyz in China. They are known in China as Kēěrkèzī zú (simplified Chinese: 柯尔克孜族; traditional Chinese: 柯爾克孜族).

Kyrgyz in Qing China

Kyrgyz leaders requested Qing officials to grant them titles and honors.[1]

The Kyrgyz traditional homeland between the expanding Russian and Qing Empires gradually came under attack from external military forces, and was subsequently reduced in size as the Russians and Qing annexed territory. The area, now known as Kyrgyzstan, is part of a much larger geo-political area known as Central Asia which in turn contains a variety of ethnolinguistic groups including Uzbeks, Oirots, Kazakhs, Turkmen, Tajiks, Mongols and Uyghurs. In the case of the Kyrgyz, the area that would become a geographical political entity was demarcated by the Chinese and the Russians. According to Steven Parham in his book “China’s Borderlands: The Faultline of Central Asia”, the border that would mark the ends of China and Russia was “not drawn by those it came to divide.”[2] While it is theorized that the Kyrgyz originated along the Yenisei River in modern day Siberia, the plains of Central Asia is considered to be the traditional homeland of the Kyrgyz.[3] During the Russian Empire’s encroachment into Central Asia, the Kyrgyz were subjugated to a series of atrocities that caused them to cross the border into Qing territory. Historically, the Kyrgyz had moved freely between the then contemporary borders of Russia and China; however, after the Qing push westward under the Qianlong Emperor and the Tsarist push South-Eastward the traditional nomadic lands that the Kyrgyz had inhabited were constricted and eventually swallowed up by the land-hungry dynasties.

Kyrgyz attitudes towards Russians was initially neutral as their first interaction with the Russian Empire was in the context of Russo-Kazakh fighting, specifically the Russian attack on the Khan of Kokand in the 1850s.[4] Prior to Russian expansion into traditional Kyrgyz lands, the Kazakhs had begun a series of raids on Kyrgyz settlements in an attempt to increase their authority in the region as well as drum up support and popularity amongst the local inhabitants. Thus upon the arrival of the Cossacks (who had been fighting against the Kazakhs since the 1730s), the Kyrgyz were excited to gain an ally that was militarily superior to the Kazakhs, despite also being militarily superior to themselves. In 1860 Cossacks from the Russian Empire sacked the city of Bishkek, the centre of Kyrgyz life, and annexed the region for the empire. Despite the taking of their capital city, the Kyrgyz were supportive of the Russians. This is due to the fact that the Kyrgyz had grown to dislike their Khan, who had in turn been put in place by the Kazakhs, whom the Tsar hoped to depose. By 1865 the Kyrgyz were fully subordinate to the Russians and by 1895 Turkmenistan had been fully incorporated into the Russian Empire.[5]

Kyrgyz attitudes towards the Chinese was considerably more varied. As a tribal union made up of various individual tribal groups each headed by their own chief, to say that the Chinese subjugated all Kyrgyz is false both historically and ethnologically. What can be said; however, is that the Kyrgyz in the eastern part of Turkistan were increasingly subjugated to the expansionist and violent tendencies of the Qing Emperor, while the Kyrgyz in the rest of Turkistan supported the resistance of their brethren in the east.[6] Historically, Kyrgyz peoples had interacted with the Jungars (Dzungars), and other Mongol groups, many of whom had been incorporated into the banner system used by the Manchus during the Ming-Qing transition.[2] The sudden absence of Mongol presence to the north meant that Kyrgyz tribes could relax. However, the Jungar presence in the region was still dominate over Kyrgyz and proved to be adversarial. The Jungars would eventually succumb to Qing expansion into Xinjiang during the Dzungar Genocide of 1757. After the explosion of the Jungars, ethnic Han Chinese poured into Xinjiang essentially replacing the lands that they had dominated. Thus the Kyrgyz had traded one dominant group for another, and the Han would prove to be just as destructive to the Kyrgyz as their predecessors had.

Kyrygz life post-Jungar saw the rise of settlement, subjugation to Chinese political and military systems, and the end of self-governance and autonomy. Kyrgyz, and indeed other Central Asian groups), now had to embrace the new Chinese imperial system, it marked “the moment in which Kyrgyz and Pamiri first encountered the political system that was to force local leaders to acknowledge a new logic of interaction based on exclusive loyalty to a state, due to their belonging on territory claimed by that state”.[2] This theme of settlement and suzerainty would continue to be an aspect of Kyrgyz life into the present. The integration of the Kyrgyz, as well as the other ethnic groups which lived in East Turkistan, into China as Xinjiang marked the beginning of modern China as a multi-ethnic state which stretched well past China proper and the Han-Manchu population.

Kyrgyz-Qing relations in the 19th century were decisively more violent as uprising throughout Xinjiang led to attacks on Chinese establishments and individuals by Turkic peoples, including the Kyrgyz. During the Kokand revolt, the Kyrgyz played a secondary role, occasionally aiding the Qing and occasionally revolting. The Kyrgyz took an opportunistic approach to rebelling against the Qing, especially during the 15 year long Dungan Revolt. Led by Siddiq Beg, it was common for Kyrgyz to revolt against the Qing when other Turkic peoples or Chinese Muslims did. It was just as easy for them to support the Qing when the tables would turn, as they would eventually resulting in a Qing victory in Xinjiang.

In the 19th century, Russian settlers on traditional Kirghiz land drove a lot of the Kirghiz over the border to China, causing their population to increase in China.[7] Compared to Russian controlled areas, more benefits were given to the Muslim Kirghiz on the Chinese controlled areas. Russian settlers fought against the Muslim nomadic Kirghiz, which led the Russians to believe that the Kirghiz would be a liability in any conflict against China. The Muslim Kirghiz were sure that in an upcoming war, that China would defeat Russia.[8]

Kyrgyz in The People's Republic of China

To escape Russians slaughtering them in 1916, Kyrgyz escaped in the "Urkun" mass flight to China.[9]

The Kirghiz of Xinjiang revolted in the 1932 Kirghiz rebellion, and also participated in the Battle of Kashgar (1933), and the Battle of Kashgar (1934).

They are found mainly in the Kizilsu Kirghiz Autonomous Prefecture in the southwestern part of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, with a smaller remainder found in the neighboring Wushi (Uqturpan), Aksu, Shache (Yarkand), Yingisar, Taxkorgan and Pishan (Guma), and in Tekes, Zhaosu (Monggolkure), Emin (Dorbiljin), Bole (Bortala), Jinghev (Jing) and Gongliu County in northern Xinjiang.[10]

A peculiar group, also included under the "Kyrgyz nationality" by the PRC official classification, are the so-called "Fuyu Kyrgyz". It is a group of several hundred Yenisei Kirghiz (Khakas people)[11] people whose forefathers were relocated from the Yenisei river region to Dzungaria by the Dzungar Khanate in the 17th century, and upon defeat of the Dzungars by the Qing dynasty, were relocated from Dzungaria to Manchuria in the 18th century, and who now live in Wujiazi Village in Fuyu County, Heilongjiang Province. Their language (the "Fuyü Gïrgïs dialect") is related to the Khakas language.

Certain segments of the Kyrgyz in China are followers of Tibetan Buddhism.[12][13][14][15][16][17]

Culture

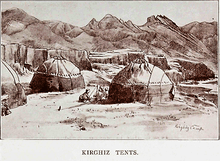

The majority of the Kyrgyz in China are herders and they raise and care for sheep and camels. Their language and culture is very similar to the Kazakhs in China.[18] Others live in sedentary towns and villages. The Islam practiced by the Kyrgyz of China incorporates many elements of shamanism and traditional practices.[19]

Common dress for Kyrgyz men includes black or blue sleeveless long gowns made out of camel hair, sheep skin, or cotton cloth (in the summer). This robe is usually worn over a white embroidered shirt and leather trousers. Both genders wear leather boots but women's boots are embroidered as well. Kyrgyz women commonly wear a wide collarless jacket and vest over a long dress. Clothing accessories include leather belts which nomadic Kyrgyz tend to hang a flint (to start a fire) or a small knife on. Women routinely wear silver chains in their hair. Both the men and women wear a small corduroy skullcap which is sometimes placed over a high-topped leather hat. Women occasionally wear a bright headscarf over their cap.[19]

Notable Kyrgyz Chinese

- Kelanbaike Makan (Latin Kyrgyz Language: Korambek Makhan, born: 1992), Chinese basketballer

- Ishaq Beg Munonov - ethnic Kyrgyz leader in Xinjiang, China during the first half of the 20th century.

See also

References

- Henry Luce Foundation Professor of East Asian Studies Nicola Di Cosmo; Nicola Di Cosmo; Don J Wyatt (16 August 2005). Political Frontiers, Ethnic Boundaries and Human Geographies in Chinese History. Routledge. pp. 362–. ISBN 978-1-135-79095-0.

- Parham, Steven (2017-02-14). China's Borderlands: The Faultline of Central Asia. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781786721259.

- Hays, Jeffrey. "KYRGYZ IN CHINA: HISTORY AND CULTURE | Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- Roudik, Peter (2007). The History of the Central Asian Republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 51. ISBN 9780313340130.

- Roudik, Peter (2007). The History of the Central Asian Republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 52. ISBN 9780313340130.

- Roudik, Peter (2007). The History of the Central Asian Republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313340130.

- Alexander Douglas Mitchell Carruthers, Jack Humphrey Miller (1914). Unknown Mongolia: a record of travel and exploration in north-west Mongolia and Dzungaria, Volume 2. Lippincott. p. 345. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- Alex Marshall (22 November 2006). The Russian General Staff and Asia, 1860-1917. Routledge. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-1-134-25379-1.

- Sydykova, Zamira (20 January 2016). "Commemorating the 1916 Massacres in Kyrgyzstan? Russia Sees a Western Plot". The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst.

- "The Kyrgyz – Children of Manas. Кыргыздар – Манастын балдары". Petr Kokaisl, Pavla Kokaislova (2009). pp.173–191. ISBN 80-254-6365-6

- Giovanni Stary; Alessandra Pozzi; Juha Antero Janhunen; Michael Weiers (2006). Tumen Jalafun Jecen Aku: Manchu Studies in Honour of Giovanni Stary. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 112–. ISBN 978-3-447-05378-5.

- Mitchell, Laurence, p. 25

- West, Barbara A., p. 441

- 柯尔克孜族. China.com.cn (in Chinese). Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- "The Kyrgyz – Children of Manas. Кыргыздар – Манастын балдары". Petr Kokaisl, Pavla Kokaislova (2009). p.4. ISBN 80-254-6365-6

- "The Kyrgyz – Children of Manas. Кыргыздар – Манастын балдары". Petr Kokaisl, Pavla Kokaislova (2009). pp.185–188. ISBN 80-254-6365-6

- "The Kyrgyz – Children of Manas. Кыргыздар – Манастын балдары". Petr Kokaisl, Pavla Kokaislova (2009). pp.259–260. ISBN 80-254-6365-6

- Dillon, Michael (1996). China's Muslims. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. pp. 10. ISBN 0195875044.

- Elliot, Sheila Hollihan (2006). Muslims in China. Philadelphia: Mason Crest Publishers. pp. 63-64. ISBN 1-59084-880-2.

External links

- Photo album of Chinese Kyrgyz, 2007 (Website of Central Asia) from Petr Kokaisl, www.central-asia.su