Turkish people

Turkish people or the Turks (Turkish: Türkler), also known as Anatolian Turks (Turkish: Anadolu Türkleri), are a Turkic ethnic group and nation living mainly in Turkey and speaking Turkish, the most widely spoken Turkic language. They are the largest ethnic group in Turkey, as well as by far the largest ethnic group among the Turkic peoples. Ethnic Turkish minorities exist in the former lands of the Ottoman Empire. In addition, a Turkish diaspora has been established with modern migration, particularly in Western Europe.

Turks from the Central Asia settled in Anatolia in the 11th century, through the conquests of the Seljuk Turks. The region then began to transform from a predominantly Greek Christian society into a Turkish Muslim one.[80] The Ottoman Empire came to rule much of the Balkans, the Caucasus, the Middle East (excluding Iran), and North Africa over the course of several centuries. The empire lasted until the end of the First World War, when it was defeated by the Allies and partitioned. Following the Turkish War of Independence that ended with the Turkish National Movement retaking much of the territory lost to the Allies, the Movement abolished the Ottoman sultanate on 1 November 1922 and proclaimed the Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1923. Not all Ottomans were Muslims and not all Ottoman Muslims were Turks, but by 1923, the majority of people living within the borders of the new Turkish republic identified as Turks.

Article 66 of the Turkish Constitution defines a "Turk" as "anyone who is bound to the Turkish state through the bond of citizenship". While the legal use of the term "Turkish" as it pertains to a citizen of Turkey is different from the term's ethnic definition,[81][82] the majority of the Turkish population (an estimated 70–75 percent) is of Turkish ethnicity.[83] The vast majority of Turks are Muslims.[72][73][74][75]

Etymology and ethnic identity

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Turkish people |

|---|

|

|

|

|

The ethnonym "Turk" may have first been discerned in Herodotus' (c. 484–425 BC) reference to Targitas, a king of the Scythians;[84] furthermore, during the first century AD., Pomponius Mela refers to the "Turcae" in the forests north of the Sea of Azov, and Pliny the Elder lists the "Tyrcae" among the people of the same area.[84] The first definite references to the "Turks" mainly come from Chinese sources which date back to the sixth century. In these sources, "Turk" appears as "Tujue" (Chinese: 突厥; Wade–Giles: T’u-chüe), which referred to the Göktürks.[85][86]

In the 19th century, the word Türk only referred to Anatolian villagers. The Ottoman ruling class identified themselves as Ottomans, not usually as Turks.[87] In the late 19th century, as the Ottoman upper classes adopted European ideas of nationalism the term Türk took on a much more positive connotation.[88]

During Ottoman times, the millet system defined communities on a religious basis, and a residue of this remains in that Turkish villagers commonly consider as Turks only those who profess the Sunni faith. Turkish Jews, Christians, or even Alevis may be considered non-Turks.[89] In the early 20th century the Young Turks abandoned Ottoman nationalism in favor of the Turkish nationalism, while adopting the name Turks, which was finally imposed in the Turkish Republic. Article 66 of the Turkish Constitution defines a "Turk" as anyone who is "bound to the Turkish state through the bond of citizenship."[90]

History

Prehistory, Ancient era and Early Middle Ages

Anatolia was first inhabited by hunter-gatherers during the Paleolithic era, and in antiquity was inhabited by various ancient Anatolian peoples.[91][j] After Alexander the Great's conquest in 334 BC, the area was Hellenized, and by the first century BC it is generally thought that the native Anatolian languages, themselves earlier newcomers to the area, as a result of the Indo-European migrations, became extinct.[92][93]

The early Turkic peoples lived somewhere between Central Asia and northwestern China, with genetic data pointing to southern Mongolia and northern China, as semi-agricultural group, but later started their expansion with a predominantly nomadic life style.[94] In Central Asia, the earliest surviving Turkic-language texts, the eighth-century Orkhon inscriptions, were erected by the Göktürks in the sixth century CE, and include words not common to Turkic but found in unrelated Inner Asian languages.[95] Although the ancient Turks were nomadic, they traded wool, leather, carpets, and horses for wood, silk, vegetables and grain, as well as having large ironworking stations in the south of the Altai Mountains during the 600s CE. Most of the Turkic peoples were followers of Tengrism, sharing the cult of the sky god Tengri, although there were also adherents of Manichaeism, Nestorian Christianity and Buddhism.[96][84] However, during the Muslim conquests, the Turks entered the Muslim world proper as slaves, the booty of Arab raids and conquests.[84] The Turks began converting to Islam after Muslim conquest of Transoxiana through the efforts of missionaries, Sufis, and merchants. Although initiated by the Arabs, the conversion of the Turks to Islam was filtered through Persian and Central Asian culture. Under the Umayyads, most were domestic servants, whilst under the Abbasid Caliphate, increasing numbers were trained as soldiers.[84] By the ninth century, Turkish commanders were leading the caliphs’ Turkish troops into battle. As the Abbasid Caliphate declined, Turkish officers assumed more military and political power taking over or establishing provincial dynasties with their own corps of Turkish troops.[84]

Seljuk era

During the 11th century the Seljuk Turks who were admirers of the Persian civilization grew in number and were able to occupy the eastern province of the Abbasid Empire. By 1055, the Seljuk Empire captured Baghdad and began to make their first incursions into the edges of Anatolia.[97] When the Seljuk Turks won the Battle of Manzikert against the Byzantine Empire in 1071, it opened the gates of Anatolia to them.[98] Although ethnically Turkish, the Seljuk Turks appreciated and became the purveyors of the Persian culture rather than the Turkish culture.[99][100] Nonetheless, the Turkish language and Islam were introduced and gradually spread over the region and the slow transition from a predominantly Christian and Greek-speaking Anatolia to a predominantly Muslim and Turkish-speaking one was underway.[98]

In dire straits, the Byzantine Empire turned to the West for help setting in motion the pleas that led to the First Crusade.[101] Once the Crusaders took Iznik, the Seljuk Turks established the Sultanate of Rum from their new capital, Konya, in 1097.[98] By the 12th century the Europeans had begun to call the Anatolian region "Turchia" or "Turkey", meaning "the land of the Turks".[102] The Turkish society of Anatolia was divided into urban, rural and nomadic populations;[103] the other Turkoman (Turkmen) tribes who had also swept into Anatolia at the same time as the Seljuk Turks were those who kept their nomadic ways.[98] These tribes were more numerous than the Seljuk Turks, and rejecting the sedentary lifestyle, adhered to an Islam impregnated with animism and shamanism from their central Asian steppeland origins, which then mixed with new Christian influences. From this popular and syncretist Islam, with its mystical and revolutionary aspects, sects such as the Alevis and Bektashis emerged.[98] Furthermore, the intermarriage between the Turks and local inhabitants, as well as the conversion of many to Islam, also increased the Turkish-speaking Muslim population in Anatolia.[98][104]

By 1243, at the Battle of Köse Dağ, the Mongols defeated the Seljuk Turks and became the new rulers of Anatolia, and in 1256, the second Mongol invasion of Anatolia caused widespread destruction. Particularly after 1277, political stability within the Seljuk territories rapidly disintegrated, leading to the strengthening of Turkoman principalities in the western and southern parts of Anatolia called the "beyliks".[105]

Beyliks era

When the Mongols defeated the Seljuk Turks and conquered Anatolia, the Turks became the vassals of the Ilkhans who established their own empire in the vast area which stretched from present-day Afghanistan to present-day Turkey.[106] As the Mongols occupied more lands in Asia Minor, the Turks moved further into western Anatolia and settled in the Seljuk-Byzantine frontier.[106] By the last decades of the 13th century, the Ilkhans and their Seljuk vassals lost control over much of Anatolia to these Turkoman peoples.[106] A number of Turkish lords managed to establish themselves as rulers of various principalities, known as "Beyliks" or emirates. Amongst these beyliks, along the Aegean coast, from north to south, stretched the beyliks of Karasi, Saruhan, Aydin, Menteşe and Teke. Inland from Teke was Hamid and east of Karasi was the beylik of Germiyan.

To the north-west of Anatolia, around Söğüt, was the small and, at this stage, insignificant, Ottoman beylik. It was hemmed in to the east by other more substantial powers like Karaman on Iconium, which ruled from the Kızılırmak River to the Mediterranean. Although the Ottomans were only a small principality among the numerous Turkish beyliks, and thus posed the smallest threat to the Byzantine authority, their location in north-western Anatolia, in the former Byzantine province of Bithynia, became a fortunate position for their future conquests. The Latins, who had conquered the city of Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, established a Latin Empire (1204–61), divided the former Byzantine territories in the Balkans and the Aegean among themselves, and forced the Byzantine Emperors into exile at Nicaea (present-day Iznik). From 1261 onwards, the Byzantines were largely preoccupied with regaining their control in the Balkans.[106] Toward the end of the 13th century, as Mongol power began to decline, the Turcoman chiefs assumed greater independence.[107]

Ottoman Empire

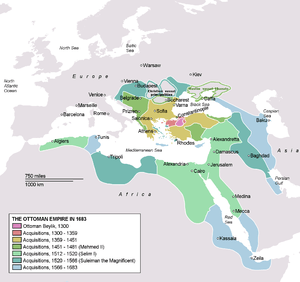

Under its founder, Osman I, the nomadic Ottoman beylik expanded along the Sakarya River and westward towards the Sea of Marmara. Thus, the population of western Asia Minor had largely become Turkish-speaking and Muslim in religion.[106] It was under his son, Orhan I, who had attacked and conquered the important urban center of Bursa in 1326, proclaiming it as the Ottoman capital, that the Ottoman Empire developed considerably. In 1354, the Ottomans crossed into Europe and established a foothold on the Gallipoli Peninsula while at the same time pushing east and taking Ankara.[108][109] Many Turks from Anatolia began to settle in the region which had been abandoned by the inhabitants who had fled Thrace before the Ottoman invasion.[110] However, the Byzantines were not the only ones to suffer from the Ottoman advance for, in the mid-1330s, Orhan annexed the Turkish beylik of Karasi. This advancement was maintained by Murad I who more than tripled the territories under his direct rule, reaching some 100,000 square miles (260,000 km2), evenly distributed in Europe and Asia Minor.[111] Gains in Anatolia were matched by those in Europe; once the Ottoman forces took Edirne (Adrianople), which became the capital of the Ottoman Empire in 1365, they opened their way into Bulgaria and Macedonia in 1371 at the Battle of Maritsa.[112] With the conquests of Thrace, Macedonia, and Bulgaria, significant numbers of Turkish emigrants settled in these regions.[110] This form of Ottoman-Turkish colonization became a very effective method to consolidate their position and power in the Balkans. The settlers consisted of soldiers, nomads, farmers, artisans and merchants, dervishes, preachers and other religious functionaries, and administrative personnel.[113]

In 1453, Ottoman armies, under Sultan Mehmed II, conquered Constantinople.[111] Mehmed reconstructed and repopulated the city, and made it the new Ottoman capital.[114] After the Fall of Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire entered a long period of conquest and expansion with its borders eventually going deep into Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.[115] Selim I dramatically expanded the empire's eastern and southern frontiers in the Battle of Chaldiran and gained recognition as the guardian of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.[116] His successor, Suleiman the Magnificent, further expanded the conquests after capturing Belgrade in 1521 and using its territorial base to conquer Hungary, and other Central European territories, after his victory in the Battle of Mohács as well as also pushing the frontiers of the empire to the east.[117] Following Suleiman's death, Ottoman victories continued, albeit less frequently than before. The island of Cyprus was conquered, in 1571, bolstering Ottoman dominance over the sea routes of the eastern Mediterranean.[118] However, after its defeat at the Battle of Vienna, in 1683, the Ottoman army was met by ambushes and further defeats; the 1699 Treaty of Karlowitz, which granted Austria the provinces of Hungary and Transylvania, marked the first time in history that the Ottoman Empire actually relinquished territory.[119]

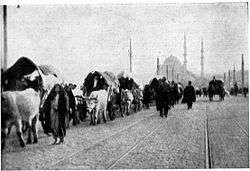

By the 19th century, the empire began to decline when ethno-nationalist uprisings occurred across the empire. Thus, the last quarter of the 19th and the early part of the 20th century saw some 7–9 million Muslim refugees (Turks and some Circassians, Bosnians, Georgians, etc.) from the lost territories of the Caucasus, Crimea, Balkans, and the Mediterranean islands migrate to Anatolia and Eastern Thrace.[120] By 1913, the government of the Committee of Union and Progress started a program of forcible Turkification of non-Turkish minorities.[121][122] By 1914, the World War I broke out, and the Turks scored some success in Gallipoli during the Battle of the Dardanelles in 1915. During World War I, the government of the Committee of Union and Progress continued to implement its Turkification policies, which affected non-Turkish minorities, such as the Armenians during the Armenian Genocide and the Greeks during various campaigns of ethnic cleansing and expulsion.[123][124][125][126][127] In 1918, the Ottoman Government agreed to the Mudros Armistice with the Allies.

The Treaty of Sèvres —signed in 1920 by the government of Mehmet VI— dismantled the Ottoman Empire. The Turks, under Mustafa Kemal, rejected the treaty and fought the Turkish War of Independence, resulting in the abortion of that text, never ratified,[128] and the abolition of the Sultanate. Thus, the 623-year-old Ottoman Empire ended.[129]

Modern era

Once Mustafa Kemal Atatürk led the Turkish War of Independence against the Allied forces that occupied the former Ottoman Empire, he united the Turkish Muslim majority and successfully led them from 1919 to 1922 in overthrowing the occupying forces out of what the Turkish National Movement considered the Turkish homeland.[130] The Turkish identity became the unifying force when, in 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed and the newly founded Republic of Turkey was formally established. Atatürk's presidency was marked by a series of radical political and social reforms that transformed Turkey into a secular, modern republic with civil and political equality for sectarian minorities and women.[131]

Throughout the 1920s and the 1930s, Turks, as well as other Muslims, from the Balkans, the Black Sea, the Aegean islands, the island of Cyprus, the Sanjak of Alexandretta (Hatay), the Middle East, and the Soviet Union continued to arrive in Turkey, most of whom settled in urban north-western Anatolia.[132][133] The bulk of these immigrants, known as "Muhacirs", were the Balkan Turks who faced harassment and discrimination in their homelands.[132] However, there were still remnants of a Turkish population in many of these countries because the Turkish government wanted to preserve these communities so that the Turkish character of these neighbouring territories could be maintained.[134] One of the last stages of ethnic Turks immigrating to Turkey was between 1940 and 1990 when about 700,000 Turks arrived from Bulgaria. Today, between a third and a quarter of Turkey's population are the descendants of these immigrants.[133]

Geographic distribution

Traditional areas of Turkish settlement

Turkey

In the latter half of the 11th century, the Seljuks began settling in the eastern regions of Anatolia. In 1071, the Seljuk Turks defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert, beginning the enlargement of their empire and sphere of influence in Anatolia; the Turkish language and Islam were introduced to Anatolia and gradually spread over the region.[135] The slow transition from a predominantly Christian and Greek-speaking Anatolia to a predominantly Muslim and Turkish-speaking one was underway.[136]

Ethnic Turks make up between 70% to 75% of Turkey's population.[1]

Cyprus

The Turkish Cypriots are the ethnic Turks whose Ottoman Turkish forebears colonised the island of Cyprus in 1571. About 30,000 Turkish soldiers were given land once they settled in Cyprus, which bequeathed a significant Turkish community. In 1960, a census by the new Republic's government revealed that the Turkish Cypriots formed 18.2% of the island's population.[137] However, once inter-communal fighting and ethnic tensions between 1963 and 1974 occurred between the Turkish and Greek Cypriots, known as the "Cyprus conflict", the Greek Cypriot government conducted a census in 1973, albeit without the Turkish Cypriot populace. A year later, in 1974, the Cypriot government's Department of Statistics and Research estimated the Turkish Cypriot population was 118,000 (or 18.4%).[138] A coup d'état in Cyprus on 15 July 1974 by Greeks and Greek Cypriots favouring union with Greece (also known as "Enosis") was followed by military intervention by Turkey whose troops established Turkish Cypriot control over the northern part of the island.[139] Hence, census's conducted by the Republic of Cyprus have excluded the Turkish Cypriot population that had settled in the unrecognised Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.[138] Between 1975 and 1981, Turkey encouraged its own citizens to settle in Northern Cyprus; a report by CIA suggests that 200,000 of the residents of Cyprus are Turkish.

Balkans

Ethnic Turks continue to inhabit certain regions of Greece, North Macedonia, Kosovo, Romania, and Bulgaria since they first settled there during Ottoman period.

Modern diaspora

Western Europe

After World War II, West Germany began to experience its greatest economic boom ("Wirtschaftswunder") and in 1961 invited the Turks as guest workers ("Gastarbeiter") to make up for the shortage of workers. The concept of the Gastarbeiter continued with Turkey bearing agreements with Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands in 1964, with France in 1965; and with Sweden in 1967.[142]

Current estimates suggests that there are approximately 9 million Turks living in Europe, excluding those who live in Turkey.[143] Modern immigration of Turks to Western Europe began with Turkish Cypriots migrating to the United Kingdom in the early 1920s when the British Empire annexed Cyprus in 1914 and the residents of Cyprus became subjects of the Crown. However, Turkish Cypriot migration increased significantly in the 1940s and 1950s due to the Cyprus conflict. Conversely, in 1944, Turks who were forcefully deported from Meskheti in Georgia during the Second World War, known as the Meskhetian Turks, settled in Eastern Europe (especially in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine). By the early 1960s, migration to Western and Northern Europe increased significantly from Turkey when Turkish "guest workers" arrived under a "Labour Export Agreement" with Germany in 1961, followed by a similar agreement with the Netherlands, Belgium and Austria in 1964; France in 1965; and Sweden in 1967.[144][145][146] More recently, Bulgarian Turks, Romanian Turks, and Western Thrace Turks have also migrated to Western Europe.

North America

Compared to Turkish immigration to Europe, migration to North America has been relatively small. According to the US Census Bureau 196,222 Americans in 2013[18] were of Turkish descent. However, the actual number of Turks is considerably larger, as a significant number of ethnic Turks have migrated to North America not just from Turkey but also from the Balkans (such as Bulgaria and North Macedonia), Cyprus, and the former Soviet Union.[147] Hence, the Turkish American community is currently estimated to number about 500,000.[21][19] Regarding the Turkish Canadian community, Statistics Canada reports that 63,955 Canadians in the 2016 census listed "Turk" as an ethnic origin, including those who listed more than one origin.[29]

The largest concentration of Turkish Americans are in New York City, and Rochester, New York; Washington, D.C.; and Detroit, Michigan. The majority of Turkish Canadians live in Ontario, mostly in Toronto, and there is also a sizable Turkish community in Montreal, Quebec. With regards to the 2010 United States Census, the U.S government was determined to get an accurate count of the American population by reaching segments, such as the Turkish community, that are considered hard to count, a good portion of which falls under the category of foreign-born immigrants.[20] The Assembly of Turkish American Associations and the US Census Bureau formed a partnership to spearhead a national campaign to count people of Turkish origin with an organisation entitled "Census 2010 SayTurk" (which has a double meaning in Turkish, "Say" means "to count" and "to respect") to identify the estimated 500,000 Turks now living in the United States.[20]

Oceania

A notable scale of Turkish migration to Australia began in the late 1940s when Turkish Cypriots began to leave the island of Cyprus for economic reasons, and then, during the Cyprus conflict, for political reasons, marking the beginning of a Turkish Cypriot immigration trend to Australia.[148] The Turkish Cypriot community were the only Muslims acceptable under the White Australia Policy;[149] many of these early immigrants found jobs working in factories, out in the fields, or building national infrastructure.[150] In 1967, the governments of Australia and Turkey signed an agreement to allow Turkish citizens to immigrate to Australia.[151] Prior to this recruitment agreement, there were fewer than 3,000 people of Turkish origin in Australia.[152] According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, nearly 19,000 Turkish immigrants arrived from 1968 to 1974.[151] They came largely from rural areas of Turkey, approximately 30% were skilled and 70% were unskilled workers.[153] However, this changed in the 1980s when the number of skilled Turks applying to enter Australia had increased considerably.[153] Over the next 35 years the Turkish population rose to almost 100,000.[152] More than half of the Turkish community settled in Victoria, mostly in the north-western suburbs of Melbourne.[152] According to the 2006 Australian Census, 59,402 people claimed Turkish ancestry;[154] however, this does not show a true reflection of the Turkish Australian community as it is estimated that between 40,000 and 120,000 Turkish Cypriots[155][156][157][158] and 150,000 to 200,000 mainland Turks[159][160] live in Australia. Furthermore, there has also been ethnic Turks who have migrated to Australia from Bulgaria,[161] Greece,[162] Iraq,[163] and North Macedonia.[162]

Former Soviet Union

The Turkish presence in the Meskheti region of Georgia began with the Turkish military expedition of 1578.[164] However, due to the ordered deportation of over 115,000 Meskhetian Turks from their homeland in 1944, during the Second World War, the majority settled in Central Asia.[165] According to the 1989 Soviet Census, which was the last Soviet Census, 106,000 Meskhetian Turks lived in Uzbekistan, 50,000 in Kazakhstan, and 21,000 in Kyrgyzstan.[165] However, in 1989, the Meshetian Turks who had settled in Uzbekistan became the target of a pogrom in the Fergana valley, which was the principal destination for Meskhetian Turkish deportees, after an uprising of nationalism by the Uzbeks.[165] The riots had left hundreds of Turks dead or injured and nearly 1,000 properties were destroyed; thus, thousands of Meskhetian Turks were forced into renewed exile.[165] The majority of Meskhetian Turks, about 70,000, went to Azerbaijan, whilst the remainder went to various regions of Russia (especially Krasnodar Krai), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine.[165][166] Soviet authorities recorded many Meskhetian Turks as belonging to other nationalities such as "Azeri", "Kazakh", "Kyrgyz", and "Uzbek".[165][167] Hence, official census's have not shown a true reflection of the Turkish population; for example, according to the 2009 Azerbaijani census, there were 38,000 Turks living in the country;[168] yet in 1999, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees stated that there were 100,000 Meskhetian Turks living in the country.[169] Furthermore, in 2001, the Baku Institute of Peace and Democracy suggested that there was between 90,000 and 110,000 Meskhetian Turks living in Azerbaijan.[65]

Culture

Arts and Architecture

Turkish architecture reached its peak during the Ottoman period. Ottoman architecture, influenced by Seljuk, Byzantine and Islamic architecture, came to develop a style all of its own.[170] Overall, Ottoman architecture has been described as a synthesis of the architectural traditions of the Mediterranean and the Middle East.[171]

As Turkey successfully transformed from the religion-based former Ottoman Empire into a modern nation-state with a very strong separation of state and religion, an increase in the modes of artistic expression followed. During the first years of the republic, the government invested a large amount of resources into fine arts; such as museums, theatres, opera houses and architecture. Diverse historical factors play important roles in defining the modern Turkish identity. Turkish culture is a product of efforts to be a "modern" Western state, while maintaining traditional religious and historical values.[172] The mix of cultural influences is dramatized, for example, in the form of the "new symbols of the clash and interlacing of cultures" enacted in the works of Orhan Pamuk, recipient of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature.[173]

Traditional Turkish music include Turkish folk music (Halk müziği), Fasıl and Ottoman classical music (Sanat müziği) that originates from the Ottoman court.[174] Contemporary Turkish music include Turkish pop music, rock, and Turkish hip hop genres.[174]

Science

Notable individuals

Notable individuals include Nureddin, Yunus Emre, Takiyüddin, Şerafeddin Sabuncuoğlu, Bâkî, Hayâlî, Haji Bektash Veli, Ali Kuşçu, Hezârfen Ahmed Çelebi, Lagâri Hasan Çelebi, Piri Reis, Namık Kemal, İbrahim Şinasi, Hüseyin Avni Lifij, Faik Ali Ozansoy, Mimar Kemaleddin, İştirakçi Hilmi, Mustafa Suphi, Ethem Nejat, Halid Ziya Uşaklıgil, Rıza Tevfik Bölükbaşı, Latife Uşşaki, Feriha Tevfik, Fatma Aliye Topuz, Keriman Halis Ece, Zeki Rıza Sporel, Cahide Sonku, Süleyman Seyyid, Abdülhak Hâmid Tarhan, Besim Ömer Akalın, Orhan Veli Kanık, Abidin Dino, Ahmet Ziya Akbulut, Nazmi Ziya Güran, Tanburi Büyük Osman Bey, Vecihi Hürkuş, Bedriye Tahir, Halide Edib Adıvar, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Mehmet Emin Yurdakul, Tevfik Fikret, Nâzım Hikmet, Hulusi Behçet, Nuri Demirağ, Fahrelnissa Zeid, Leyla Gencer, Ahmet Ertegün, Metin Oktay, Fikri Alican, Feza Gürsey, Ismail Akbay, Oktay Sinanoğlu, Gazi Yaşargil, Behram Kurşunoğlu, Fethullah Gülen, Mehmet Öz, Tansu Çiller, Cahit Arf, Muhtar Kent, Efe Aydan, Neslihan Demir, Orhan Pamuk and Aziz Sancar.

Language

The Turkish language also known as Istanbul Turkish is a southern Oghuz branch of the Turkic languages. It is natively spoken by the Turkish people in Turkey, Balkans, the island of Cyprus, Meskhetia, and other areas of traditional settlement that formerly, in whole or part, belonged to the Ottoman Empire. Turkish is the official language of Turkey. In the Balkans, Turkish is still spoken by Turkish minorities who still live there, especially in Bulgaria, Greece (mainly in Western Thrace), Kosovo, North Macedonia, Romania (mainly in Dobruja) and the Republic of Moldova (mainly in Gagauzia).[175] The Turkish language was introduced to Cyprus with the Ottoman conquest in 1571 and became the politically dominant, prestigious language, of the administration.[176]

One important change to Turkish literature was enacted in 1928, when Mustafa Kemal initiated the creation and dissemination of a modified version of the Latin alphabet to replace the Arabic alphabet based Ottoman script. Over time, this change, together with changes in Turkey's system of education, would lead to more widespread literacy in the country.[177] Modern standard Turkish is based on the dialect of Istanbul.[178] Nonetheless, dialectal variation persists, in spite of the levelling influence of the standard used in mass media and the Turkish education system since the 1930s.[179] The terms ağız or şive often refer to the different types of Turkish dialects.

There are three major Anatolian Turkish dialect groups spoken in Turkey: the West Anatolian dialect (roughly to the west of the Euphrates), the East Anatolian dialect (to the east of the Euphrates), and the North East Anatolian group, which comprises the dialects of the Eastern Black Sea coast, such as Trabzon, Rize, and the littoral districts of Artvin.[180][181] The Balkan Turkish dialects are considerably closer to standard Turkish and do not differ significantly from it, despite some contact phenomena, especially in the lexicon.[182] In the post-Ottoman period, Cypriot Turkish was relatively isolated from standard Turkish and had strong influences by the Cypriot Greek dialect. The condition of coexistence with the Greek Cypriots led to a certain bilingualism whereby Turkish Cypriots knowledge of Greek was important in areas where the two communities lived and worked together.[183] The linguistic situation changed radically in 1974, when the island was divided into a Greek south and a Turkish north (Northern Cyprus). Today, the Cypriot Turkish dialect is being exposed to increasing standard Turkish through immigration from Turkey, new mass media, and new educational institutions.[176] The Meskhetian Turks speak an Eastern Anatolian dialect of Turkish, which hails from the regions of Kars, Ardahan, and Artvin.[184] The Meskhetian Turkish dialect has also borrowed from other languages (including Azerbaijani, Georgian, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Russian, and Uzbek), which the Meskhetian Turks have been in contact with during the Russian and Soviet rule.[184]

Religion

According to the CIA factbook, 99.8% of the population in Turkey is Muslim, most of them being Sunni (Hanafi). The remaining 0.2% is mostly Christian and Jewish.[185] There are also some estimated 10 to 15 million Alevi Muslims in Turkey.[186] Christians in Turkey include Assyrians/Syriacs,[187] Armenians, and Greeks.[188] Jewish people in Turkey include those that descend from Sephardic Jews who escaped Spain in 15th century and Greek-speaking Jews from Byzantine times.[189] There is an ethnic Turkish Protestant Christian community most of them came from recent Muslim Turkish backgrounds, rather than from ethnic minorities.[77][190][191][192]

According to KONDA research, only 9.7% of the population described themselves as "fully devout," while 52.8% described themselves as "religious."[193] 69.4% of the respondents reported that they or their wives cover their heads (1.3% reporting chador), although this rate decreases in several demographics: 53% in ages 18–28, 27.5% in university graduates, 16.1% in masters-or-higher-degree holders.[72] Turkey has also been a secular state since the republican era.[194] According to a poll, 90% of respondents said the country should be defined as secular in the new Constitution that is being written.[195]

Genetics

An autosomal DNA study of Turks in 2014 by Can Alkan found that the Turkic East Asian impact on modern Turkey was 21.7%[196] A study in 2015 found that "Previous genetic studies have generally used Turks as representatives of ancient populations from Turkey. Our results show that Turks are genetically shifted towards modern Central Asians, a pattern consistent with a history of mixture with populations from this region".[197]

A study involving mitochondrial analysis of a Byzantine-era population, whose samples were gathered from excavations in the archaeological site of Sagalassos, found that the Byzantine population of Sagalassos might have left a genetic signature in the modern Turkish populations.[198] Modern-day samples from the nearby town of Ağlasun showed that lineages of East Eurasian descent assigned to macro-haplogroup M were found in the modern samples from Ağlasun. This haplogroup is significantly more frequent in Ağlasun (15%) than in Byzantine Sagalassos.[199] One study found that results pointed out that language (Turkish) in Anatolia might not have been replaced by the elites, but by a large group of people, which means there was no elite assimilation in Anatolia.[200] Another study found the Circassians are closest to the Turkish population among sampled European (French, Italian, Sardinian), Middle Eastern (Druze, Palestinian), and Central (Kyrgyz, Hazara, Uygur), South (Pakistani), and East Asian (Mongolian, Han) populations.[201]

Notes

^ a: According to the Home Affairs Committee this includes 300,000 Turkish Cypriots.[202] However, some estimates suggest that the Turkish Cypriot community in the UK has reached between 350,000[203] to 400,000.[204][205]

^ b: Includes people of mixed ethnic background.

^ c: A further 10,000–30,000 people from Bulgaria live in the Netherlands. The majority are Bulgarian Turks and are the fastest-growing group of immigrants in the Netherlands.[206]

^ d: This includes Turkish settlers. 2,000 of these Turkish Cypriots currently reside in the southern part of the island, the rest on the northern.[207]

^ e: This figure only includes Turkish citizens. Therefore, this also includes ethnic minorities from Turkey; however, it does not include ethnic Turks who have either been born and/or have become naturalised citizens. Furthermore, these figures do not include ethnic Turkish minorities from Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece, Iraq, Kosovo, Macedonia, Romania or any other traditional area of Turkish settlement because they are registered as citizens from the country they have immigrated from rather than their ethnic Turkish identity.

^ f: In addition to Turkish citizens, this figure includes people with ancestral background related to Turkey, so it includes ethnic minorities of Turkey.

^ g: This figure only includes Turks of Western Thrace. A further 5,000 live in the Rhodes and Kos.[208] In addition to this, 8,297 immigrants live in Greece.[209]

^ h: These figures only include the Meskhetian Turks. According to official census's there were 38,000 Turks in Azerbaijan (2009),[168] 97,015 in Kazakhstan (2009),[210] 39,133 in Kyrgyzstan (2009),[211] 109,883 in Russia (2010),[212] and 9,180 in Ukraine (2001).[213] A further 106,302 Turks were recorded in Uzbekistan's last census in 1989[214] although the majority left for Azerbaijan and Russia during the 1989 pogroms in the Ferghana Valley. Official data regarding the Turks in the former Soviet Union is unlikely to provide a true indication of their population as many have been registered as "Azeri", "Kazakh", "Kyrgyz", and "Uzbek".[215] In Kazakhstan only a third of them were recorded as Turks, the rest had been arbitrarily declared members of other ethnic groups.[216][217] Similarly, in Azerbaijan, much of the community is officially registered as "Azerbaijani"[218] even though the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reported, in 1999, that 100,000 Meskhetian Turks were living there.[64]

^ i: A further 30,000 Bulgarian Turks live in Sweden.[219]

^ j: "The history of Turkey encompasses, first, the history of Anatolia before the coming of the Turks and of the civilizations—Hittite, Thracian, Hellenistic, and Byzantine—of which the Turkish nation is the heir by assimilation or example. Second, it includes the history of the Turkish peoples, including the Seljuks, who brought Islam and the Turkish language to Anatolia. Third, it is the history of the Ottoman Empire, a vast, cosmopolitan, pan-Islamic state that developed from a small Turkish amirate in Anatolia and that for centuries was a world power."[220]

^ k: The Turks are also defined by the country of origin. Turkey, once Asia Minor or Anatolia, has a very long and complex history. It was one of the major regions of agricultural development in the early Neolithic and may have been the place of origin and spread of lndo-European languages at that time. The Turkish language was imposed on a predominantly lndo-European-speaking population (Greek being the official language of the Byzantine empire), and genetically there is very little difference between Turkey and the neighboring countries. The number of Turkish invaders was probably rather small and was genetically diluted by the large number of aborigines."

"The consideration of demographic quantities suggests that the present genetic picture of the aboriginal world is determined largely by the history of Paleolithic and Neolithic people, when the greatest relative changes in population numbers took place."[221]

References

- CIA. "The World Factbook". Archived from the original on 2 July 2017.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- CIA. "The World Factbook". Archived from the original on 12 June 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "KKTC 2011 NUFUS VE KONUT SAYIMI" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- "Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund - Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus - Fachserie 1 Reihe 2.2 - 2017" (PDF). Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). p. 61. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Fransa Diyanet İşleri Türk İslam Birliği. "2011 YILI DİTİB KADIN KOLLARI GENEL TOPLANTISI PARİS DİTİB'DE YAPILDI". Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- Home Affairs Committee 2011, 38

- "UK immigration analysis needed on Turkish legal migration, say MPs". The Guardian. 1 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- Federation of Turkish Associations UK (19 June 2008). "Short history of the Federation of Turkish Associations in UK". Archived from the original on 10 January 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- "CBS Statline". opendata.cbs.nl.

- Netherlands Info Services. "Dutch Queen Tells Turkey 'First Steps Taken' On EU Membership Road". Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- Dutch News (6 March 2007). "Dutch Turks swindled, AFM to investigate". Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi 2008, 11.

- "Turkey's ambassador to Austria prompts immigration spat". BBC News. 10 November 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- CBN. "Turkey's Islamic Ambitions Grip Austria". Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- "Population par nationalité, sexe, groupe et classe d'âges au 1er janvier 2010 - - Home". Archived from the original on 22 December 2011.

- King Baudouin Foundation 2008, 5.

- De Morgen. "Koning Boudewijnstichting doorprikt clichés rond Belgische Turken". Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- U.S. Census Bureau. "TOTAL ANCESTRY REPORTED Universe: Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported 2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. "Immigration and Ethnicity: Turks". Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- The Washington Diplomat. "Census Takes Aim to Tally'Hard to Count' Populations". Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Farkas 2003, 40.

- Ständige ausländische Wohnbevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit, am Ende des Jahres Archived 30 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Swiss Federal Statistical Office, accessed 6 October 2014

- "Australian Government Department of Immigration and Border Protection" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "Old foes, new friends". The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 April 2005. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- Presidency of the Republic of Turkey (2010). "Turkey-Australia: "From Çanakkale to a Great Friendship". Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- OECD (2009). "International Questionnaire: Migrant Education Policies in Response to Longstanding Diversity: TURKEY" (PDF). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. p. 3.

- Population of Sweden 31.12.2018 born in Turkey, which includes Turks, Assyrians, Kurds and others. [http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101E/FodelselandArK/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=daf5d50d-a31c-4045-8bfb-b4801e1c3cf9}}

- Statistikbanken. "Danmarks Statistik". Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables". statcan.gc.ca.

- "I cittadini non comunitari regolarmente soggiornanti Ascolta". 5 August 2014. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Council of Europe 2007, 131.

- Triana, María (2017), Managing Diversity in Organizations: A Global Perspective, Taylor & Francis, p. 168, ISBN 978-1-317-42368-3,

Turkmen, Iraqi citizens of Turkish origin, are the third largest ethnic group in Iraq after Arabs and Kurds and they are said to number about 3 million of Iraq's 34.7 million citizens according to the Iraqi Ministry of Planning.

- Bassem, Wassim (2016). "Iraq's Turkmens call for independent province". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016.

Turkmens are a mix of Sunnis and Shiites and are the third-largest ethnicity in Iraq after Arabs and Kurds, numbering about 3 million out of the total population of about 34.7 million, according to 2013 data from the Iraqi Ministry of Planning.

- Maisel, Sebastian (2016), Yezidis in Syria: Identity Building among a Double Minority, Lexington Books, p. 15, ISBN 978-0739177754

- Pierre, Beckouche (2017), "The Country Reports: Syria", Europe's Mediterranean Neighbourhood, Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 178–180, ISBN 978-1786431493,

Before 2011, Syria's population was 74% Sunni Muslim, including...Turkmen (4%)...

- Akar 1993, 95.

- Karpat 2004, 12.

- Al-Akhbar. "Lebanese Turks Seek Political and Social Recognition". Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- "Tension adds to existing wounds in Lebanon". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- Ahmed, Yusra (2015), Syrian Turkmen refugees face double suffering in Lebanon, Zaman Al Wasl, retrieved 11 October 2016

- Syrian Observer (2015). "Syria's Turkmen Refugees Face Cruel Reality in Lebanon". Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria (2011). "2011 Population Census in the Republic of Bulgaria (Final data)" (PDF). National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria.

- Sosyal 2011, 369.

- Bokova 2010, 170.

- "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Macedonia, 2002" (PDF). Stat.gov.mk. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Republic of Macedonia State Statistical Office 2005, 34.

- Knowlton 2005, 66.

- Abrahams 1996, 53.

- "GREEK HELSINKI MONITOR". Minelres.lv. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Demographics of Greece". European Union National Languages. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- "Destroying Ethnic Identity: The Turks of Greece" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "Turks Of Western Thrace". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- (in Romanian) "Comunicat de presă privind rezultatele definitive ale Recensământului Populaţiei şi Locuinţelor – 2011", at the 2011 Romanian census site; accessed 11 July 2013

- Phinnemore 2006, 157.

- Constantin, Goschin & Dragusin 2008, 59.

- 2011 census in the Republic of Kosovo

- 2010 Russia census

- Ryazantsev 2009, 172.

- "Агентство Республики Казахстан по статистике. Этнодемографический сборник Республики Казахстан 2014". Stat.gov.kz. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 13.

- Kyrgyz 2009 census

- IRIN Asia (9 June 2005). "KYRGYZSTAN: Focus on Mesketian Turks". Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- "Wayback Machine". 30 November 2012. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- UNHCR 1999, 14.

- NATO Parliamentary Assembly. "Minorities in the South Caucasus: Factor of Instability?". Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- Council of Europe 2006, 23.

- Blacklock 2005, 8

- State Statistics Service of Ukraine. "Ukrainian Census (2001):The distribution of the population by nationality and mother tongue". Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- Pentikäinen & Trier 2004, 20.

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 14.

- Çalışma ve Sosyal Güvenlik Bakanlığı. "YURTDIŞINDAKİ VATANDAŞLARIMIZLA İLGİLİ SAYISAL BİLGİLER (31.12.2009 tarihi itibarıyla)". Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Religion, Secularism and the Veil in Daily Life Survey" (PDF). Konda Arastirma. September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- "IHGD - Soru Cevap - Azınlıklar". Sorular.rightsagenda.org. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "THE ALEVI OF ANATOLIA: TURKEY'S LARGEST MINORITY". Angelfire.com. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Shi'a". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "ReportDGResearchSocialValuesEN2.PDF" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "TURKEY - Christians in eastern Turkey worried despite church opening". Hurriyetdailynews.com. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "BBC News - When Muslims become Christians". News.bbc.co.uk. 21 April 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Sahadeo, Jeff; Zanca, Russell (2007). Everyday life in Central Asia : past and present. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 22–3. ISBN 978-0253013538.

- Okur, Samim Akgönül ; translated from Turkish by Sila (2013). The minority concept in the Turkish context : practices and perceptions in Turkey, Greece, and France. Leiden [etc.]: Brill. p. 136. ISBN 978-9004222113.

- Bayir, Derya (22 April 2016). Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law. ISBN 978-1317095798.

- "Turkey". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency]. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Leiser 2005, 837.

- Stokes & Gorman 2010, 707.

- Findley 2005, 21.

- (Kushner 1997: 219; Meeker 1971: 322)

- (Kushner 1997: 220–221)

- (Meeker 1971: 322)

- "Turkish Citizenship Law" (PDF). 29 May 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- Stokes & Gorman 2010, 721.

- Theo van den Hout (27 October 2011). The Elements of Hittite. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-139-50178-1. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- Sharon R. Steadman; Gregory McMahon (15 September 2011). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000–323 BCE). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537614-2. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- "Transeurasian ancestry: A case of farming/language dispersal". ResearchGate. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Findley 2005, 39

- Frederik Coene, The Caucasus-An Introduction, p.77 Taylor & Francis, 2009

- Duiker & Spielvogel 2012, 192.

- Darke 2011, 16.

- Chaurasia 2005, 181.

- Bainbridge 2009, 33.

- Duiker & Spielvogel 2012, 193.

- Ágoston 2010, 574.

- Delibaşı 1994, 7.

- International Business Publications 2004, 64

- Somel 2003, 266.

- Ágoston 2010, xxv.

- Kia 2011, 1.

- Fleet 1999, 5.

- Kia 2011, 2.

- Köprülü 1992, 110.

- Ágoston 2010, xxvi.

- Fleet 1999, 6.

- Eminov 1997, 27.

- Kermeli 2010, 111.

- Kia 2011, 5.

- Quataert 2000, 21.

- Kia 2011, 6.

- Quataert 2000, 24.

- Levine 2010, 28.

- Karpat 2004, 5–6.

- Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons, ed. (2012). Century of Genocide. Routledge. pp. 118–124. ISBN 978-1135245504.

"By 1913 the advocates of liberalism had lost out to radicals in the party who promoted a program of forcible Turkification.

- Jwaideh, Wadie (2006). The Kurdish national movement : its origins and development (1. ed.). Syracuse, NY: Syracuse Univ. Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0815630937.

With the crushing of opposition elements, the Young Turks simultaneously launched their program of forcible Turkification and the creation of a highly centralized administrative system."

- Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' crime against humanity: the Armenian genocide and ethnic cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0691153339.

- Bjornlund, Matthias (March 2008). "The 1914 cleansing of Aegean Greeks as a case of violent Turkification". Journal of Genocide Research. 10 (1): 41–57. doi:10.1080/14623520701850286. ISSN 1462-3528.

In 1914, the aim of Turkification was not to exterminate but to expel as many Greeks of the Aegean region as possible as not only a "security measure," but as an extension of the policy of economic and cultural boycott, while at the same time creating living space for the muhadjirs that had been driven out of their homes under equally brutal circumstances.

- Akçam, Taner (2005). From Empire to Republic: Turkish Nationalism and the Armenian Genocide. London: Zed Books. p. 115. ISBN 9781842775271.

...the initial stages of the Turkification of the Empire, which affected by attacks on its very heterogeneous structure, thereby ushering in a relentless process of ethnic cleansing that eventually, through the exigencies and opportunities of the First World War, culminated in the Armenian Genocide.

- Rummel, Rudolph J. (1996). Death By Government. Transaction Publishers. p. 235. ISBN 9781412821292.

Through this genocide and the forced deportation of the Greeks, the nationalists completed the Young Turk's program-the Turkification of Turkey and the elimination of a pretext for Great Power meddling.

- J.M. Winter, ed. (2003). America and the Armenian Genocide of 1915. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780511163821.

The devising of a scheme of a correlative Turkification of the Empire, or what was left of it, included the cardinal goal of the liquidation of that Empire’s residual non-Turkish elements. Given their numbers, their concentration in geo-strategic locations, and the troublesome legacy of the Armenian Question, the Armenians were targeted as the prime object for such a liquidation.

- Rozakēs, Chrēstos L (31 August 1987). The Turkish Straits. ISBN 978-9024734641. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Levine 2010, 29.

- Göcek 2011, 22.

- Göcek 2011, 23.

- Çaǧaptay 2006, 82.

- Bosma, Lucassen & Oostindie 2012, 17

- Çaǧaptay 2006, 84.

- Melek Tekin: Türk Tarihi Ansiklopedisi, Milliyet yayınları, İstanbul, 1991, p. 237.

- Rafis Abazov (2009). Culture and Customs of Turkey. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1071. ISBN 978-0-313-34215-8. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- Hatay 2007, 22.

- Hatay 2007, 23.

- "UNFICYP: United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus". United Nations.

- Kötter et al. 2003, 55.

- Haviland et al. 2010, 675.

- Abadan-Unat 2011, 12.

- Sosyal 2011, 367.

- Akgündüz 2008, 61.

- Kasaba 2008, 192.

- Twigg et al. 2005, 33

- Karpat 2004, 627.

- Hüssein 2007, 17

- Cleland 2001, 24

- Hüssein 2007, 19

- Hüssein 2007, 196

- Hopkins 2011, 116

- Saeed 2003, 9

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. "20680-Ancestry (full classification list) by Sex Australia". Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- TRNC Ministry of Foreign Affairs. "Briefing Notes on the Cyprus Issue". Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- Kibris Gazetesi. "Avustralya'daki Kıbrıslı Türkler ve Temsilcilik..." Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- BRT. "AVUSTURALYA'DA KIBRS TÜRKÜNÜN SESİ". Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Star Kıbrıs. "Sözünüzü Tutun". Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- "Old foes, new friends". The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 April 2005. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- "Avustralyalı Türkler'den, TRT Türk'e tepki". Milliyet. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2006). "Community Information Summary:Bulgaria" (PDF). Australian Government. p. 2.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2007). "2006 Census Ethnic Media Package". Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship (2006). "Community Information Summary:Iraq" (PDF). Australian Government. p. 1.

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 4.

- UNHCR 1999b, 20.

- UNHCR 1999b, 21.

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 1

- The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan. "Population by ethnic groups". Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- UNHCR 1999a, 14.

- Necipoğlu, Gülru (1995). Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Volume 12. Leiden : E.J. Brill. p. 60. ISBN 9789004103146. OCLC 33228759. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- Grabar, Oleg (1985). Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Volume 3. Leiden : E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-9004076112. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- Ibrahim Kaya (2004). Social Theory and Later Modernities: The Turkish Experience. Liverpool University Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-85323-898-0. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- "Pamuk wins Nobel Literature prize". BBC. 12 October 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- Martin Dunford; Terry Richardson (3 June 2013). The Rough Guide to Turkey. Rough Guides. pp. 647–. ISBN 978-1-4093-4005-8. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- Johanson 2011, 734–738.

- Johanson 2011, 738.

- Lester 1997; Wolf-Gazo 1996

- George L. Campbell (1 September 2003). Concise Compendium of the World's Languages. Taylor & Francis. pp. 547–. ISBN 978-0-415-11392-2. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Johanson 2001, 16.

- Brendemoen 2002, 27.

- Brendemoen 2006, 227.

- Friedman 2003, 51.

- Johanson 2011, 739.

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 23

- "CIA World Factbook". CIA. March 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- Shankland, David (2003). The Alevis in Turkey: The Emergence of a Secular Islamic Tradition. Routledge (UK). ISBN 978-0-7007-1606-7.

- Pieter H. Omtzigt; Markus K. Tozman; Andrea Tyndall (2012). The Slow Disappearance of the Syriacs from Turkey: And of the Grounds of the Mor Gabriel Monastery. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-90268-9.

- Religious Freedom Report U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 15 September 2009.

- Judith R. Baskin; Kenneth Seeskin (2010). The Cambridge Guide to Jewish History, Religion, and Culture. Cambridge University Press. pp. 145–. ISBN 978-0-521-86960-7.

- "Turkish Protestants still face "long path" to religious freedom - The Christian Century". The Christian Century. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- White, Jenny (27 April 2014). Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks. ISBN 9781400851256. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "TURKEY: Protestant church closed down - Church In Chains - Ireland 🆚 An Irish voice for suffering, persecuted Christians Worldwide". Churchinchains.ie. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- KONDA (2007). "Religion, Secularism and the Veil in Daily Life Survey" (PDF). Konda Arastirma. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ahmet T. Kuru; Alfred C. Stepan (2012). Democracy, Islam, and secularism in Turkey. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-53025-5.

- "More secular, green Turkey wanted: Poll". Hürriyet Daily News. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- Alkan et al. (2014), BMC Genomics 2014, 15:963, Whole genome sequencing of Turkish genomes reveals functional private alleles and impact of genetic interactions with Europe, Asia and Africa

- Tyler-Smith, Chris; Zalloua, Pierre; Gasparini, Paolo; Comas, David; Xue, Yali; Mezzavilla, Massimo; Haber, Marc (2016). "Genetic evidence for an origin of the Armenians from Bronze Age mixing of multiple populations". European Journal of Human Genetics. 24 (6): 931–936. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.206. ISSN 1476-5438. PMC 4820045. PMID 26486470.

- Ottoni, C.; Ricaut, F. O. X.; Vanderheyden, N.; Brucato, N.; Waelkens, M.; Decorte, R. (2011). "Mitochondrial analysis of a Byzantine population reveals the differential impact of multiple historical events in South Anatolia". European Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (5): 571–576. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.230. PMC 3083616. PMID 21224890.

- Ottoni, Claudio; Rasteiro, Rita; Willet, Rinse; Claeys, Johan; Talloen, Peter; Van De Vijver, Katrien; Chikhi, Lounès; Poblome, Jeroen; Decorte, Ronny (2016). "Comparing maternal genetic variation across two millennia reveals the demographic history of an ancient human population in southwest Turkey". Royal Society Open Science. 3 (2): 150250. Bibcode:2016RSOS....350250O. doi:10.1098/rsos.150250. PMC 4785964. PMID 26998313.

- http://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/12607764/index.pdf

- Hodoğlugil, U. U.; Mahley, R. W. (2012). "Turkish Population Structure and Genetic Ancestry Reveal Relatedness among Eurasian Populations". Annals of Human Genetics. 76 (2): 128–141. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x. PMC 4904778. PMID 22332727.

- Home Affairs Committee 2011, Ev 34

- Laschet, Armin (17 September 2011). "İngiltere'deki Türkler". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Akben, Gözde (11 February 2010). "Olmalı mı Olmamalı mı?". Star Kıbrıs. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- Cemal, Akay (2 June 2011). "Dıştaki gençlerin askerlik sorunu çözülmedikçe…". Kıbrıs Gazetesi. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- The Sophia Echo. "Turkish Bulgarians fastest-growing group of immigrants in The Netherlands". Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- Hatay 2007, 40.

- Clogg 2002, 84.

- MigrantsInGreece. "Data on immigrants in Greece, from Census 2001, Legalization applications 1998, and valid Residence Permits, 2004" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- Агентство РК по статистике. "ПЕРЕПИСЬ НАСЕЛЕНИЯ РЕСПУБЛИКИ КАЗАХСТАН 2009 ГОДА" (PDF). p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic. "Population and Housing Census 2009" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Демоскоп Weekly. "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 г. Национальный состав населения Российской Федерации". Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- State statistics committee of Ukraine – National composition of population, 2001 census (Ukrainian)

- Демоскоп Weekly. "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 1.

- Khazanov 1995, 202.

- Babak, Vaisman & Wasserman 2004, 253.

- Helton, Arthur C. (1998). "Chapter Two: Contemporary Conditions and Dilemmas". Meskhetian Turks: Solutions and Human Security. Open Society Institute. Archived from the original on 15 April 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- Laczko, Stacher & von Koppenfels 2002, 187.

- Steven A. Glazer (22 March 2011). "Turkey: Country Studies". Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- L. Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza; Paolo, Menozzi; Alberto, Piazza (1994). The history and geography of human genes. Princeton University Press. pp. 243, 299. ISBN 978-0-691-08750-4. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

Bibliography

- Abadan-Unat, Nermin (2011), Turks in Europe: From Guest Worker to Transnational Citizen, Berghahn Books, ISBN 978-1-84545-425-8.

- Abazov, Rafis (2009), Culture and Customs of Turkey, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0313342158.

- Akar, Metin (1993), "Fas Arapçasında Osmanlı Türkçesinden Alınmış Kelimeler", Türklük Araştırmaları Dergisi, 7: 91–110

- Abrahams, Fred (1996), A Threat to "Stability": Human Rights Violations in Macedonia, Human Rights Watch, ISBN 978-1-56432-170-1.

- Ágoston, Gábor (2010), "Introduction", in Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce Alan (eds.), Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-1438110257.

- Akar, Metin (1993), "Fas Arapçasında Osmanlı Türkçesinden Alınmış Kelimeler", Türklük Araştırmaları Dergisi, 7: 91–110

- Akgündüz, Ahmet (2008), Labour migration from Turkey to Western Europe, 1960–1974: A multidisciplinary analysis, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-7390-3.

- Aydıngün, Ayşegül; Harding, Çiğdem Balım; Hoover, Matthew; Kuznetsov, Igor; Swerdlow, Steve (2006), Meskhetian Turks: An Introduction to their History, Culture, and Resettelment Experiences, Center for Applied Linguistics, archived from the original on 29 October 2013

- Babak, Vladimir; Vaisman, Demian; Wasserman, Aryeh (2004), Political Organization in Central Asia and Azerbaijan: Sources and Documents, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7146-4838-5.

- Baedeker, Karl (2000), Egypt, Elibron, ISBN 978-1402197055.

- Bainbridge, James (2009), Turkey, Lonely Planet, ISBN 978-1741049275.

- Baran, Zeyno (2010), Torn Country: Turkey Between Secularism and Islamism, Hoover Press, ISBN 978-0817911447.

- Bennigsen, Alexandre; Broxup, Marie (1983), The Islamic threat to the Soviet State, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-7099-0619-3.

- Bokova, Irena (2010), "Recontructions of Identities: Regional vs. National or Dynamics of Cultrual Relations", in Ruegg, François; Boscoboinik, Andrea (eds.), From Palermo to Penang: A Journey Into Political Anthropology, LIT Verlag Münster, ISBN 978-3643800626

- Bogle, Emory C. (1998), Islam: Origin and Belief, University of Texas Press, ISBN 978-0292708624.

- Bosma, Ulbe; Lucassen, Jan; Oostindie, Gert (2012), "Introduction. Postcolonial Migrations and Identity Politics: Towards a Comparative Perspective", Postcolonial Migrants and Identity Politics: Europe, Russia, Japan and the United States in Comparison, Berghahn Books, ISBN 978-0857453273.

- Brendemoen, Bernt (2002), The Turkish Dialects of Trabzon: Analysis, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447045704.

- Brendemoen, Bernt (2006), "Ottoman or Iranian? An example of Turkic-Iranian language contact in East Anatolian dialects", in Johanson, Lars; Bulut, Christiane (eds.), Turkic-Iranian Contact Areas: Historical and Linguistic Aspects, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447052764.

- Brizic, Katharina; Yağmur, Kutlay (2008), "Mapping linguistic diversity in an emigration and immigration context: Case studies on Turkey and Austria", in Barni, Monica; Extra, Guus (eds.), Mapping Linguistic Diversity in Multicultural Contexts, Walter de Gruyter, p. 248, ISBN 978-3110207347.

- Brozba, Gabriela (2010), Between Reality and Myth: A Corpus-based Analysis of the Stereotypic Image of Some Romanian Ethnic Minorities, GRIN Verlag, ISBN 978-3-640-70386-9.

- Bruce, Anthony (2003), The Last Crusade. The Palestine Campaign in the First World War, John Murray, ISBN 978-0719565052.

- Çaǧaptay, Soner (2006), Islam, Secularism, and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk?, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0415384582.

- Çaǧaptay, Soner (2006), "Passage to Turkishness: immigration and religion in modern Turkey", in Gülalp, Haldun (ed.), Citizenship And Ethnic Conflict: Challenging the Nation-state, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0415368971.

- Campbell, George L. (1998), Concise Compendium of the World's Languages, Psychology Press, ISBN 978-0415160490.

- Cassia, Paul Sant (2007), Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory, and the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus, Berghahn Books, ISBN 978-1845452285.

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2005), History Of Middle East, Atlantic Publishers & Dist, ISBN 978-8126904488.

- Cleland, Bilal (2001), "The History of Muslims in Australia", in Saeed, Abdullah; Akbarzadeh, Shahram (eds.), Muslim Communities in Australia, University of New South Wales, ISBN 978-0-86840-580-3.

- Clogg, Richard (2002), Minorities in Greece, Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 978-1-85065-706-4.

- Constantin, Daniela L.; Goschin, Zizi; Dragusin, Mariana (2008), "Ethnic entrepreneurship as an integration factor in civil society and a gate to religious tolerance. A spotlight on Turkish entrepreneurs in Romania", Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies, 7 (20): 28–41

- Cornell, Svante E. (2001), Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7007-1162-8.

- Darke, Diana (2011), Eastern Turkey, Bradt Travel Guides, ISBN 978-1841623399.

- Delibaşı, Melek (1994), "The Era of Yunus Emre and Turkish Humanism", Yunus Emre: Spiritual Experience and Culture, Università Gregoriana, ISBN 978-8876526749.

- Duiker, William J.; Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2012), World History, Cengage Learning, ISBN 978-1111831653.

- Elsie, Robert (2010), Historical Dictionary of Kosovo, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-7231-8.

- Eminov, Ali (1997), Turkish and other Muslim minorities in Bulgaria, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 978-1-85065-319-6.

- Ergener, Rashid; Ergener, Resit (2002), About Turkey: Geography, Economy, Politics, Religion, and Culture, Pilgrims Process, ISBN 978-0971060968.

- Evans, Thammy (2010), Macedonia, Bradt Travel Guides, ISBN 978-1-84162-297-2.

- Farkas, Evelyn N. (2003), Fractured States and U.S. Foreign Policy: Iraq, Ethiopia, and Bosnia in the 1990s, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1403963734.

- Faroqhi, Suraiya (2005), Subjects Of The Sultan: Culture And Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-1850437604.

- Findley, Carter V. (2005), The Turks in World History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195177268.

- Fleet, Kate (1999), European and Islamic Trade in the Early Ottoman State: The Merchants of Genoa and Turkey, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521642217.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2003), Turkish in Macedonia and Beyond: Studies in Contact, Typology and other Phenomena in the Balkans and the Caucasus, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447046404.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2006), "Western Rumelian Turkish in Macedonia and adjacent areas", in Boeschoten, Hendrik; Johanson, Lars (eds.), Turkic Languages in Contact, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447052122.

- Gogolin, Ingrid (2002), Guide for the Development of Language Education Policies in Europe: From Linguistic Diversity to Plurilingual Education (PDF), Council of Europe.

- Göcek, Fatma Müge (2011), The Transformation of Turkey: Redefining State and Society from the Ottoman Empire to the Modern Era, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-1848856110.

- Hatay, Mete (2007), Is the Turkish Cypriot Population Shrinking? (PDF), International Peace Research Institute, ISBN 978-82-7288-244-9.

- Haviland, William A.; Prins, Harald E. L.; Walrath, Dana; McBride, Bunny (2010), Anthropology: The Human Challenge, Cengage Learning, ISBN 978-0-495-81084-1.

- Hizmetli, Sabri (1953), "Osmanlı Yönetimi Döneminde Tunus ve Cezayir'in Eğitim ve Kültür Tarihine Genel Bir Bakış" (PDF), Ankara Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, 32: 1–12

- Hodoğlugil, Uğur; Mahley, Robert W. (2012), "Turkish Population Structure and Genetic Ancestry Reveal Relatedness among Eurasian Populations", Annals of Human Genetics, 76 (2): 128–141, doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x, PMC 4904778, PMID 22332727

- Home Affairs Committee (2011), Implications for the Justice and Home Affairs area of the accession of Turkey to the European Union (PDF), The Stationery Office, ISBN 978-0-215-56114-5

- Hopkins, Liza (2011), "A Contested Identity: Resisting the Category Muslim-Australian", Immigrants & Minorities, 29 (1): 110–131, doi:10.1080/02619288.2011.553139.

- Hüssein, Serkan (2007), Yesterday & Today: Turkish Cypriots of Australia, Serkan Hussein, ISBN 978-0-646-47783-1.

- İhsanoğlu, Ekmeleddin (2005), "Institutionalisation of Science in the Medreses of Pre-Ottoman and Ottoman Turkey", in Irzik, Gürol; Güzeldere, Güven (eds.), Turkish Studies in the History And Philosophy of Science, Springer, ISBN 978-1402033322.

- Ilican, Murat Erdal (2011), "Cypriots, Turkish", in Cole, Jeffrey (ed.), Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1598843026.

- International Business Publications (2004), Turkey Foreign Policy And Government Guide, International Business Publications, ISBN 978-0739762820.

- International Crisis Group (2008), Turkey and the Iraqi Kurds: Conflict or Cooperation?, Middle East Report N°81 –13 November 2008: International Crisis Group, archived from the original on 12 January 2011CS1 maint: location (link)

- International Crisis Group (2010). "Cyprus: Bridging the Property Divide". International Crisis Group. Archived from the original on 3 November 2011..

- Jawhar, Raber Tal’at (2010), "The Iraqi Turkmen Front", in Catusse, Myriam; Karam, Karam (eds.), Returning to Political Parties?, Co-éditions, The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, pp. 313–328, ISBN 978-1-886604-75-9.

- Johanson, Lars (2001), Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map (PDF), Stockholm: Svenska Forskningsinstitutet i Istanbul

- Johanson, Lars (2011), "Multilingual states and empires in the history of Europe: the Ottoman Empire", in Kortmann, Bernd; Van Der Auwera, Johan (eds.), The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide, Volume 2, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3110220254

- Kaplan, Robert D. (2002), "Who Are the Turks?", in Villers, James (ed.), Travelers' Tales Turkey: True Stories, Travelers' Tales, ISBN 978-1885211828.

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2000), "Historical Continuity and Identity Change or How to be Modern Muslim, Ottoman, and Turk", in Karpat, Kemal H. (ed.), Studies on Turkish Politics and Society: Selected Articles and Essays, BRILL, ISBN 978-9004115620.

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2004), Studies on Turkish Politics and Society: Selected Articles and Essays, BRILL, ISBN 978-9004133228.

- Kasaba, Reşat (2008), The Cambridge History of Turkey: Turkey in the Modern World, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-62096-3.

- Kasaba, Reşat (2009), A Moveable Empire: Ottoman Nomads, Migrants, and Refugees, University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0295989488.

- Kermeli, Eugenia (2010), "Byzantine Empire", in Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce Alan (eds.), Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-1438110257.

- Khazanov, Anatoly Michailovich (1995), After the USSR: Ethnicity, Nationalism and Politics in the Commonwealth of Independent States, University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 978-0-299-14894-2.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2011), Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-0313064029.

- King Baudouin Foundation (2008), "Diaspora philanthropy – a growing trend" (PDF), Turkish communities and the EU, King Baudouin Foundation, archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2009.

- Kirişci, Kemal (2006), "Migration and Turkey: the dynamics of state, society and politics", in Kasaba, Reşat (ed.), The Cambridge History of Turkey: Turkey in the Modern World, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521620963.

- Knowlton, MaryLee (2005), Macedonia, Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 978-0-7614-1854-2.

- Köprülü, Mehmet Fuat (1992), The Origins of the Ottoman Empire, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0791408209.

- Kötter, I; Vonthein, R; Günaydin, I; Müller, C; Kanz, L; Zierhut, M; Stübiger, N (2003), "Behçet's Disease in Patients of German and Turkish Origin- A Comparative Study", in Zouboulis, Christos (ed.), Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Volume 528, Springer, ISBN 978-0-306-47757-7.

- Kurbanov, Rafik Osman-Ogly; Kurbanov, Erjan Rafik-Ogly (1995), "Religion and Politics in the Caucasus", in Bourdeaux, Michael (ed.), The Politics of Religion in Russia and the New States of Eurasia, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-1-56324-357-8.

- Kushner, David (1997). "Self-Perception and Identity in Contemporary Turkey". Journal of Contemporary History. 32 (2): 219–233. doi:10.1177/002200949703200206.

- Laczko, Frank; Stacher, Irene; von Koppenfels, Amanda Klekowski (2002), New challenges for Migration Policy in Central and Eastern Europe, Cambridge University Press, p. 187, ISBN 978-9067041539.

- Leiser, Gary (2005), "Turks", in Meri, Josef W. (ed.), Medieval Islamic Civilization, Routledge, p. 837, ISBN 978-0415966900.

- Leveau, Remy; Hunter, Shireen T. (2002), "Islam in France", in Hunter, Shireen (ed.), Islam, Europe's Second Religion: The New Social, Cultural, and Political Landscape, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0275976095.

- Levine, Lynn A. (2010), Frommer's Turkey, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0470593660.

- Minahan, James (2002), Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: L-R, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-32111-5.

- Meeker, M. E. (1971). "The Black Sea Turks: Some Aspects of Their Ethnic and Cultural Background". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 2 (4): 318–345. doi:10.1017/s002074380000129x.

- National Institute of Statistics (2002), Population by ethnic groups, regions, counties and areas (PDF), Romania – National Institute of Statistics

- Oçak, Ahmet Yaçar (2012), "Islam in Asia Minor", in El Hareir, Idris; M'Baye, Ravane (eds.), Different Aspects of Islamic Culture: Vol.3: The Spread of Islam Throughout the World, UNESCO, ISBN 978-9231041532.

- Orhan, Oytun (2010), The Forgotten Turks: Turkmens of Lebanon (PDF), ORSAM, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- OSCE (2010), "Community Profile: Kosovo Turks", Kosovo Communities Profile, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe.

- Oxford Business Group (2008), The Report: Algeria 2008, Oxford Business Group, ISBN 978-1-902339-09-2.

- Özkaya, Abdi Noyan (2007), "Suriye Kürtleri: Siyasi Etkisizlik ve Suriye Devleti'nin Politikaları" (PDF), Review of International Law and Politics, 2 (8), archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2011.

- Öztürkmen, Ali; Duman, Bilgay; Orhan, Oytun (2011), Suriye'de değişim ortaya çıkardığı toplum: Suriye Türkmenleri, ORSAM.

- Pan, Chia-Lin (1949), "The Population of Libya", Population Studies, 3 (1): 100–125, doi:10.1080/00324728.1949.10416359

- Park, Bill (2005), Turkey's policy towards northern Iraq: problems and perspectives, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-415-38297-7

- Phillips, David L. (2006), Losing Iraq: Inside the Postwar Reconstruction Fiasco, Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-05681-1

- Phinnemore, David (2006), The EU and Romania: Accession and Beyond, The Federal Trust for Education & Research, ISBN 978-1-903403-78-5.

- Polian, Pavel (2004), Against Their will: The History and Geography of Forced Migrations in the USSR, Central European University Press, ISBN 978-963-9241-68-8.

- Quataert, Donald (2000), The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521633284.

- Republic of Macedonia State Statistical Office (2005), Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Macedonia, 2002 (PDF), Republic of Macedonia – State Statistical Office

- Romanian National Institute of Statistics (2011), Comunicat de presă privind rezultatele provizorii ale Recensământului Populaţiei şi Locuinţelor – 2011 (PDF), Romania-National Institute of Statistics

- Ryazantsev, Sergey V. (2009), "Turkish Communities in the Russian Federation" (PDF), International Journal on Multicultural Societies, 11 (2): 155–173.

- Saeed, Abdullah (2003), Islam in Australia, Allen & Unwin, ISBN 978-1-86508-864-8.

- Saunders, John Joseph (1965), "The Turkish Irruption", A History of Medieval Islam, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415059145.

- Scarce, Jennifer M. (2003), Women's Costume of the Near and Middle East, Routledge, ISBN 978-0700715602.

- Seher, Cesur-Kılıçaslan; Terzioğlu, Günsel (2012), "Families Immigrating from Bulgaria to Turkey Since 1878", in Roth, Klaus; Hayden, Robert (eds.), Migration In, From, and to Southeastern Europe: Historical and Cultural Aspects, Volume 1, LIT Verlag Münster, ISBN 978-3643108951.

- Shaw, Stanford J. (1976), History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey Volume 1, Empire of the Gazis: The Rise and Decline of the Ottoman Empire 1280–1808, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521291637.

- Somel, Selçuk Akşin (2003), Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0810843325.

- Sosyal, Levent (2011), "Turks", in Cole, Jeffrey (ed.), Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1598843026.

- Stansfield, Gareth R. V. (2007), Iraq: People, History, Politics, Polity, ISBN 978-0-7456-3227-8.

- Stavrianos, Leften Stavros (2000), The Balkans Since 1453, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 978-1850655510.

- Stokes, Jamie; Gorman, Anthony (2010), "Turkic Peoples", Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-1438126760.

- Taylor, Scott (2004), Among the Others: Encounters with the Forgotten Turkmen of Iraq, Esprit de Corps Books, ISBN 978-1-895896-26-8.

- Stokes, Jamie; Gorman, Anthony (2010), "Turks: nationality", Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-1438126760.

- Tomlinson, Kathryn (2005), "Living Yesterday in Today and Tomorrow: Meskhetian Turks in Southern Russia", in Crossley, James G.; Karner, Christian (eds.), Writing History, Constructing Religion, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-5183-3.

- Turkish Embassy in Algeria (2008), Cezayir Ülke Raporu 2008, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, archived from the original on 29 September 2013.

- Twigg, Stephen; Schaefer, Sarah; Austin, Greg; Parker, Kate (2005), Turks in Europe: Why are we afraid? (PDF), The Foreign Policy Centre, ISBN 978-1903558799, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2011

- UNHCR (1999), Background Paper on Refugees and Asylum Seekers from Azerbaijan (PDF), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.