Turkmens

Turkmens (Turkmen: Türkmenler, Түркменлер, توركمنلر, [tʏɾkmɛnˈlɛɾ]; historically also the Turkmen) are a nation and Turkic ethnic group native to Central Asia, primarily the Turkmen nation state of Turkmenistan. Large communities have traditionally lived in neighboring Iran and Afghanistan; sizeable groups of Turkmens are found also in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and the North Caucasus (Stavropol Krai). They speak the Turkmen language, which is classified as a part of the Eastern Oghuz branch of the Turkic languages. Examples of other Oghuz languages are Turkish, Azerbaijani, Qashqai, Gagauz, Khorasani, and Salar.[10]

TürkmenlerТүркменлерتوركمنلر | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Turkmens in folk costume at the 20th Independence Day parade, 27 September 2011 | |

| Total population | |

| c. 6.4 million[a] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 4,948,000[1] | |

| 1,100,000[2][3] | |

| 790,000[4] | |

| 152,000[5] | |

| 46,885[6] | |

| 15,171[7] | |

| 7,709[8] | |

| 6,000[9] | |

| 5,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Turkmen | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Oghuz Turks | |

a. ^ The total figure is merely an estimation; a sum of all the referenced populations. | |

Seljuks, Khwarazmians, Qara Qoyunlu, Aq Qoyunlu, Ottomans and Afsharids are also believed to descend from the Turkmen tribes of Qiniq, Begdili, Yiva, Bayandur, Kayi and Afshar respectively.[11]

Etymology

The term “Turkmen” generally applied for the Turkic tribes had been distributed across the Near and Middle East, as well as Central Asia from the 11th century to modern times.[12] Originally, all Turkic tribes that were part of the Turkic dynastic mythological system (for example, Uigurs, Karluks, and a number of other tribes, including tribes of Western or Oghuz Turks) were designated "Turkmens". Only later did this word come to refer to a specific ethnonym. The term is thought to derive from Türk plus the Sogdian affix of similarity -myn, -men, and means "resembling a Türk" or "co-Türk".[13][14]

Another view on the etymology of the term "Turkmen" belongs to Arminius Vambery, a Hungarian scholar, who traveled all the way from Iran across the Karakum Desert to Khiva, Bukhara, and Samarkand with a purpose of establishing link between Turkic and Hungarian languages in 1863.[15] Vambery notes that the word Turkmen consists of the word "Turk" and the suffix -men (which resembles the English suffix -ship, -dom).[16] He concludes that the suffix -men or -man brings greater intensity to the word "Turk".[17]

Jean Deny’s work of Grammaire De La Langue Turque is another significant source to understand the etymology. In his work, while trying to clarify the meaning of the suffixes -men, -man, the author gives example with turk-men, that he created from the word "turc" (i.e. turk) and links it to "turcoman".[18] As J.Deny notes, the term “Turkmen” in this case would have a meaning of "the Turk of pure blood" or "thoroughbred Turk", since the "augmentative" suffix -man (or -men), possesses a sense of intensification in Turkic languages. Many prominent orientalists such as G. Nemeth[19], V. Minorsky, G. Moravcsik, O.Pritsak, H. Husameddin, I. Kafesoglu, and Louis Bazin agreed on J. Deny’s view about the suffix -man and -men having the above-mentioned meaning. While H. Husameddin notes that the term means "grand Türk"[20], L. Ligeti states that it means "true, original Turk".[21]

Today the terms are usually restricted to two Turkic groups: the Turkmen people of Turkmenistan and adjacent parts of Central Asia, and the Turkomans of Iraq and Syria.

Origins

The earliest reference to the term "Turkmen" appears in the Chinese literature as a country name.[22] Chinese encyclopedia T’ung-tién (8th century A.D) contains information where the country of Su-i or Su-de[23][24] (probably Sogd or Sogdia), which had commercial and political relations with China in the 5th century A.D., is also called T’ö-kü-Möng[25] (Turkmen country).[26]

Apart from these claims, the term "Turkmen" is used for the first time near the end of the 10th century A.D in Islamic literature by the Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi in Ahsan Al-Taqasim Fi Ma'rifat Al-Aqalim.[27] In his work, which was completed in 987 A.D, al-Muqaddasi writes about Turkmens twice while depicting the region as the frontier of the Muslim possessions in Central Asia.[28]

Towards the end of the 11th, in Divânü Lügat'it-Türk (Compendium of the Turkic Dialects), Mahmud Kashgari uses “Türkmen” synonymously with “Oğuz”.[29] He describes Oghuz as a Turkic tribe and says that Oghuz are Turkmens[30][31].

The modern Turkmen people descend from the Oghuz Turks of Transoxiana, the western portion of Turkestan, a region that largely corresponds to much of Central Asia as far east as Xinjiang. Famous historian and ruler of Khorezm of the XVII century Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur links the origin of all Turkmens to 24 Oghuz tribes in his literary work "Genealogy of the Turkmens".[32]

In the 7th century AD, Oghuz tribes had moved westward from the Altay mountains through the Siberian steppes, and settled in this region. They also penetrated as far west as the Volga basin and the Balkans. These early Turkmens are believed to have mixed with native Sogdian peoples and lived as pastoral nomads until being conquered by the Russians in the 19th century.[33]

Genetics

Haplogroup Q-M242 is commonly found in Siberia, Southeast Asia, Central Asia. This haplogroup forms a large percentages of the paternal lineages of Turkmens.

Grugni et al. (2012) found Q-M242 in 42.6% (29/68) of a sample of Turkmens from Golestan, Iran.[34] Di Cristofaro et al. (2013) found Q-M25 in 31.1% (23/74) and Q-M346 in 2.7% (2/74) for a total of 33.8% (25/74) Q-M242 in a sample of Turkmens from Jawzjan.[35] Karafet et al. (2018) found Q-M25 in 50.0% (22/44) of another sample of Turkmens from Turkmenistan.[36] Haplogroup Q have seen it's highest frequencies in the Turkmens from Karakalpakstan (mainly Yomut) at 73%.[37]

A genetic study on the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups of a Turkmen sample describes a mixture of mostly West Eurasian lineages and minority of East Eurasian lineages. Turkmens also have two unusual mtDNA markers with polymorphic characteristics, only found in Turkmens and southern Siberians.[38]

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Turkmenistan |

|

| Periods |

|

Antiquity

|

|

Early modern history |

| Related historical names of the region |

|

|

Turkmens belong to the Oghuz tribes, who originated on the periphery of Central Asia and founded gigantic empires beginning from the 3rd millennium BC. Subsequently, Turkmen tribes founded lasting dynasties in Central Asia, Middle East, Persia and Anatolia that had a profound influence on the course of history of those regions.[40] The most prominent of those dynasties were the Ghaznavids, Seljuks, Ottomans, Safavids, Afsharids and Qajars. Representatives of the Turkmen tribes of Ive and Bayandur were also the founders of the short-lived, but formidable states of Kara Koyunlu and Ak Koyunlu Turkomans respectively[41][42].

Turkmens largely survived unaffected by the Mongol period due to their semi-nomadic lifestyle and became traders along the Caspian, which led to contacts with Eastern Europe. Following the decline of the Mongols, Tamerlane conquered the area and his Timurid Empire would rule, until it too fractured, as the Safavids, Khanate of Bukhara, and Khanate of Khiva all contested the area. The expanding Russian Empire took notice of Turkmenistan's extensive cotton industry, during the reign of Peter the Great, and invaded the area. Following the decisive Battle of Geok Tepe in January 1881, a bulk of Turkmen tribes found themselves under the rule of the Russian Emperor. After the Russian Revolution, Soviet control was established by 1921, and in 1924 Turkmenistan became Soviet Socialistic Republic. Turkmenistan gained independence in 1991.

Language

Turkmen (Latin: Türkmençe, Cyrillic: Түркменче) is the language of the nation of Turkmenistan. It is spoken by over 5,200,000 people in Turkmenistan, and by roughly 3,000,000 people in other countries, including Iran, Afghanistan, and Russia.[43] Up to 30% of native speakers in Turkmenistan also claim a good knowledge of Russian, a legacy of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union.

The Turkmen language is closely related to Azerbaijani, Turkish, Gagauz, Qashqai and Crimean Tatar, sharing common linguistic features with each of those languages. There is a high degree of mutual intelligibility between these languages.[44][45] A handful of specific lexical and grammatical differences formed within the Turkmen language as spoken in Turkmenistan, Iran and Afghanistan, after more than a century of separation between the people speaking the language; mutually intelligibility, however, has been preserved.

Turkmen is not a literary language in Iran and Afghanistan, where many Turkmen tend towards bilingualism, usually conversant in the countries' different dialects of Persian, such as Dari in Afghanistan. Variations of the Persian alphabet are, however, used in Iran.

Religion

The Turkmen of Turkmenistan, like their kin in Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Iran are predominantly Muslims. According to the CIA World Factbook, Turkmenistan is 89% Muslim and 10% Eastern Orthodox. Most ethnic Russians are Orthodox Christians. The remaining 1% is unknown. A 2009 Pew Research Center report indicates a higher percentage of Muslims with 93.1% of Turkmenistan's population adhering to Islam. The great majority of Turkmen readily identify themselves as Muslims and acknowledge Islam as an integral part of their cultural heritage. However, there are some who only support a revival of the religion's status merely as an element of national revival.

Culture and society

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of Turkmenistan |

|---|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

Turkmenistan portal |

Nomadic heritage

Before the establishment of Soviet power in Central Asia, it was difficult to identify distinct ethnic groups in the region. Sub-ethnic and supra-ethnic loyalties were more important to people than ethnicity. When asked to identify themselves, most Central Asians would name their kin group, neighborhood, village, religion or the state in which they lived; the idea that a state should exist to serve an ethnic group was unknown.[46]

Most Turkmen were nomads and were not settled in cities and towns until the advent of the Soviet government. This mobile lifestyle precluded identification with anyone outside one's kin group and led to frequent conflicts between different Turkmen tribes. In collaboration with the local nationalists, the Soviet government sought to transform the Turkmen and other “backward” ethnic groups in the USSR into modern socialist nations that based their identity on a fixed territory and a common language.

The Soviet-led standardization of the Turkmen language, education, and projects to promote ethnic Turkmen in the industry, government and higher education had led growing numbers of Turkmen to identify with a larger national Turkmen culture rather than with sub-national, pre-modern forms of identity.[47] Before the Soviet era, a proverb stated that the Turkmen's home was where his horse happened to stand. After gaining independence from the Soviet Union, Turkmen historians went to great lengths to prove that the Turkmen had inhabited their current territory since time immemorial; some historians even tried to deny the nomadic heritage of the Turkmen.[48]

Turkmen lifestyle was heavily invested in horsemanship and as a prominent horse culture, Turkmen horse-breeding was an ages old tradition. In spite of changes prompted by the Soviet period, a tribe in southern Turkmenistan has remained very well known for their horses, the Akhal-Teke desert horse – and the horse breeding tradition has returned to its previous prominence in recent years.[49]

Many tribal customs still survive among modern Turkmen. Unique to Turkmen culture is kalim which is a groom's "dowry", that can be quite expensive and often results in the widely practiced tradition of bridal kidnapping.[50] In something of a modern parallel, in 2001, President Saparmurat Niyazov had introduced a state enforced "kalim", which required all foreigners who wanted to marry a Turkmen woman to pay a sum of no less than $50,000.[51] The law was abolished in March 2005.[52]

Other customs include the consultation of tribal elders, whose advice is often eagerly sought and respected. Many Turkmen still live in extended families where various generations can be found under the same roof, especially in rural areas.[50]

The music of the nomadic and rural Turkmen people reflects rich oral traditions, where epics such as Koroglu are usually sung by itinerant bards. These itinerant singers are called bakshy and sing either a cappella or with instruments such as the two-stringed lute called dutar.

Society today

_%D0%B2_%D0%94%D1%83%D1%88%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B1%D0%B5_(6).jpg)

Since Turkmenistan's independence in 1991, a cultural revival has taken place with the return of a moderate form of Islam and celebration of Novruz or New Year's Day.

Turkmen can be divided into various social classes including the urban intelligentsia and workers whose role in society is different from that of the rural peasantry. Secularism and atheism remain prominent for many Turkmen intellectuals who favor moderate social changes and often view extreme religiosity and cultural revival with some measure of distrust.[53]

The five traditional carpet designs that form motifs in the country's state emblem and flag represent the five major Turkmen tribes.

Turkmen in Iran

Turkmen rulers, successively of the Black Sheep Turkomans and White Sheep Turkomans, ruled much of Persia and surrounding countries before Shah Ismail I defeated them to begin the Safavid dynasty in 1501. Tabriz was their usual capital. There remains a relatively small population identifying as Turkmen in modern Iran.

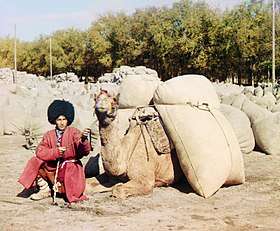

Turkmen in Afghanistan

Turkmen are another Sunni Turkic-speaking group whose language has close affinities with modern Turkish. The Afghan Turkmen population in the 1990s was estimated at around 200,000. Turkmen also reside north of the Amu Darya in Turkmenistan.[54] The original Turkmen groups came from east of the Caspian Sea into northwestern Afghanistan at various periods, particularly after the end of the nineteenth century when the Russians moved into their territory. They established settlements from Balkh Province to Herat Province, where they are now concentrated; smaller groups settled in Kunduz Province. Others came in considerable numbers as a result of the failure of the Basmachi revolts against the Bolsheviks in the 1920s.[54] Turkmen tribes, of which there are twelve major groups in Afghanistan, base their structure on genealogies traced through the male line. Senior members wield considerable authority. Formerly a nomadic and warlike people feared for their lightning raids on caravans, Turkmen in Afghanistan are farmer-herdsmen and important contributors to the economy. They brought karakul sheep to Afghanistan and are also renowned makers of carpets, which, with karakul pelts, are major hard currency export commodities. Turkmen jewelry is also highly prized.[54]

Turkmen of Stavropol Region of Russia

In the Stavropol Krai of southern Russia, there is a long established colony of Turkmen. They are often referred to as Trukhmen by the local ethnic Russian population, and sometimes use the self-designation Turkpen.[55] According to the 2010 Census of Russia, they numbered 15,048, and accounted for 0.5% of the total population of Stavropol Krai.

The Turkmens are said to have migrated into the Caucasus in the 17th century, in particular in the Mangyshlak region. These migrants belonged mainly to the Chaudorov (Chavodur), Sonchadj and Ikdir tribes. The early settlers were nomadic but over time a process of sedentarization took place. In their cultural life the Trukhmens of today differ very little from their neighbours and are now settled farmers and stockbreeders.[55]

Although the Turkmen language belongs to the Oghuz group of Turkic languages, in Stavropol it has been strongly influenced by the Nogai language, which belongs to the Kipchak group. The phonetic system, grammatical structure and to some extent also the vocabulary, have been somewhat influenced.[56]

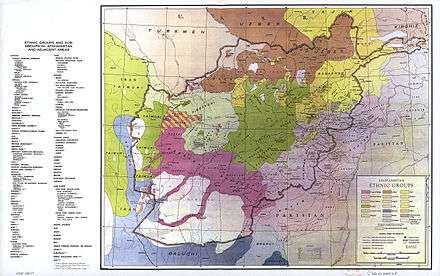

Demographics and population distribution

The Turkmen people of Central Asia live in:

- Turkmenistan, where some 85% of the population of 5,042,920 people (July 2006 est.), are ethnic Turkmen. In addition, an estimated 1,200 Turkmen refugees from northern Afghanistan currently reside in Turkmenistan due to the ravages of the Soviet–Afghan War and factional fighting in Afghanistan which saw the rise and fall of the Taliban.[57]

- Afghanistan, where as of 2006, 200,000 are ethnic Turkmen and are largely concentrated primarily along the Turkmen-Afghan border in the provinces of Faryab, Jowzjan, Samangan and Baghlan. There are also other communities in Balkh and Kunduz Provinces.

- Iran, where about 719,000 Turkmen are primarily concentrated in the provinces of Golestān and North Khorasan.[4]

- Pakistan, During the Soviet–Afghan war, Some Turkmen fled the country and settled in neighboring Pakistan. Today a small population of Turkmen reside in Pakistan mainly in Peshawar city. Their number in Pakistan is estimated to be less than 5,000. They are mainly involved in Carpet Business in Peshawar city.

See also

References

- "The World Factbook". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Ethnic Groups". Library of Congress Country Studies. 1997. Retrieved 2010-10-08. ^ Jump up to: a b

- https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/ethnic-groups-of-afghanistan.html

- "Ethnologue". Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- Alisher Ilhamov (2002). Ethnic Atlas of Uzbekistan. Open Society Institute: Tashkent.

- 2002 Russian census

- 2002 Tajikistani census (2010)

- "About number and composition population of Ukraine by data All-Ukrainian census of the population 2001". Ukraine Census 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- (PDF) https://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/home/opendoc.pdf?tbl=SUBSITES&page=SUBSITES&id=434fdc702. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "UCLA Language Materials Project: Main". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Абулгази - Родословная туркмен". Russian State Library.

- Barbara Kellner-Heinkele, “Türkmen,” The Encyclopaedia of Islam, eds. P.J. Bearman, T.H. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. Van Donzel and W. P. Heinrichs, vol. X (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 2000), pp. 682-685

- Yu. Zuev, "Early Türks: Essays on history and ideology", Almaty, Daik-Press, 2002, p. 157, ISBN 9985-4-4152-9

- Glenn E. Curtis, ed. "Origins and Early History", Turkmenistan: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1996. pg. 13

- Arminius Vambéry, The Story of my Struggles: The Memoirs of Arminius Vambéry (London, 1905), pp. 152-153

- Arminius Vambéry, The Story of my Struggles: The Memoirs of Arminius Vambéry (London, 1905), p 347

- Arminius Vambery, "The Turcomans Between the Caspian and Merv", The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 9. (1880), p.338

- J. Deny, Grammaire de la langue turque (Dialecte Osmanli) (Paris, 1921), p.326

- G. Nemeth, A honfoglaló magyarság kialakulása (Budapest, 1930), p. 58

- Ibrahim Kafesoglu, “Türkmen Adı, Manası ve Mahiyeti,” in Jean Deny Armağanı: Mélanges Jean Deny, eds. János Eckmann, Agâh Sırrı Levend and Mecdut Mansuroğlu (Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, 1958), p. 131

- Ragıp Hulûsi, Kırgız adının menşei: TM I (1925), p. 249

- V.V. Barthold, Four Studies on the History of Central Asia, p. 79

- V.V. Barthold, Four Studies on the History of Central Asia, pp. 79-80

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam: A Dictionary of the Geography, Ethnography and Biograpghy of the Muhammadan Peoples, eds. M. Th. Houtsma, A.J. Wensinck, H. A. R. Gibb, W. Heffening and E. Lévi-Provençal, vol. IV (Leyden: Late E.J. Brill Ltd., 1934), pp. 896-897

- V.V. Barthold, Four Studies on the History of Central Asia, p. 79

- V.V. Barthold, Four Studies on the History of Central Asia, p. 80

- Al-Marwazī, Sharaf Al-Zämān Tāhir Marvazī on China, the Turks and India, Arabic text (circa A.D. 1120) (English translation and commentary by V. Minorsky) (London: The Royal Asiatic Society, 1942), p. 94

- V. Minorsky, “Commentary,” in Sharaf Al-Zämān Tāhir Marvazī on China, the Turks and India, Arabic text (circa A.D. 1120) (English translation and commentary by V. Minorsky) (London: The Royal Asiatic Society, 1942), p. 94.

- Kaşgarlı Mahmud, Divânü Lügat'it-Türk, vol. I, p. 55.

- Kaşgarlı Mahmud, Divânü Lügat'it-Türk,vol. I, pp. 55-58;

- A. Zeki Velidî Togan, Oğuz Destanı: Reşideddin Oğuznâmesi, Tercüme ve Tahlili (İstanbul: Enderun Kitabevi, 1982), pp. 50-52

- Kononov А. Н. (1958). "Genealogy of the Turkmens. Introduction (in Russian)". M. AS USSR.

- Bacon, Elizabeth Emaline (1966). Amazon.com: Central Asians under Russian Rule: A Study in Culture Change (Cornell Paperbacks): Elizabeth E. Bacon, Michael M. J. Fischer: Books. ISBN 9780801492112.

- Grugni, Viola; et al. (2012). "Ancient Migratory Events in the Middle East: New Clues from the Y-Chromosome Variation of Modern Iranians". PLOS ONE. 7 (7): e41252. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041252. PMC 3399854. PMID 22815981.

- Di Cristofaro, J; Pennarun, E; Mazières, S; Myres, NM; Lin, AA; et al. (2013). "Afghan Hindu Kush: Where Eurasian Sub-Continent Gene Flows Converge". PLoS ONE. 8 (10): e76748. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076748. PMC 3799995. PMID 24204668.

- Tatiana M. Karafet, Ludmila P. Osipova, Olga V. Savina, et al. (2018), "Siberian genetic diversity reveals complex origins of the Samoyedic-speaking populations." Am J Hum Biol. 2018;e23194. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23194. DOI: 10.1002/ajhb.23194.

- Skhalyakho, Rosa; Zhabagin, Maxat; M. Yusupov, Yu; Agdzhoyan, Anastasiya (2016). "Gene pool of Turkmens from Karakalpakstan in their Central Asian context (Y-chromosome polymorphism)". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Malyarchuk, B. A.; Derenko, M. V.; Denisova, G. A.; Nassiri, M. R.; Rogaev, E. I. (1 April 2002). "Mitochondrial DNA Polymorphism in Populations of the Caspian Region and Southeastern Europe". Russian Journal of Genetics. 38 (4): 434–438. doi:10.1023/A:1015262522048. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011.

- "A Salor Turkmen kejebe trapping" HALI, March 18, 2019

- Stefano Carboni, Jean-François de Lapérouse, Historical overview - "Turkmen Jewelry: Silver Ornaments from the Marshall and Marilyn R. Wolf Collection", published by Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011

- Safa, Z. (1986). PERSIAN LITERATURE IN THE TIMURID AND TÜRKMEN PERIODS (782–907/1380–1501). In P. Jackson & L. Lockhart (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Iran (The Cambridge History of Iran, pp. 913-928). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- « The Timurid and Turkmen Dynasties of Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia », in : David J. Roxburgh, ed., The Turks: A Journey of Thousand Years, 600-1600. London, Royal Academy of Arts, 2005, pp. 192-200

- "Turkmen". Ethnologue. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Aspects of Altaic Civilization III: Proceedings of the Thirtieth Meeting of the Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, June 19-25, 1987. Psychology Press. 1996-12-13. ISBN 9780700703807.

- "Language Materials Project: Turkish". UCLA International Institute, Center for World Languages. February 2007

- Adrienne Lynn Edgar (2007). Tribal Nation: The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan. Princeton University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9781400844296.

- Adrienne Lynn Edgar (2007). Tribal Nation: The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan. Princeton University Press. p. 261. ISBN 9781400844296.

- Adrienne Lynn Edgar (2007). Tribal Nation: The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan. Princeton University Press. p. 264. ISBN 9781400844296.

- "Turkmenistan Embassy Washington". www.turkmenistanembassy.org. Archived from the original on 2012-01-27.

- "Turkmen Society". Archived from the original on 2007-03-18.

- Philip Sherwell, Price of loving a Turkmen girl is now $50,000, The Telegraph, July 22, 2001

- Gulnoza Saidazimova, Turkmenistan: Marriage Gets Cheaper As Turkmenbashi Drops $50,000 Dollar Foreigners' Fee, Radio Free Europe, June 10, 2005

- "US Library of Congress Country Studies-Turkmenistan: Social Structure". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "US Library of Congress Country Studies-Afghanistan: Turkmen".

- The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire. Eki.ee. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2013-07-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "UNHCR Begins Compiling Database of Refugees in Turkmenistan". Archived from the original on 2005-12-08.

Sources

- Bacon, Elizabeth E. Central Asians Under Russian Rule: A Study in Culture Change, Cornell University Press (1980). ISBN 0-8014-9211-4.

- Turkmenistan Pages by Ekahau

- Did the engsi hang inside or outside the yurt?

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Turkmens. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 468.