Turkic languages

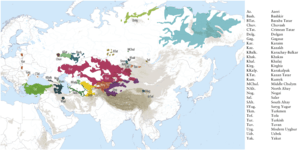

The Turkic languages are a language family of at least 35[2] documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, Central Asia and West Asia all the way to North Asia (particularly in Siberia) and East Asia. The Turkic languages originated in a region of East Asia spanning Western China to Mongolia, where Proto-Turkic is thought to have been spoken,[3] from where they expanded to Central Asia and farther west during the first millennium.[4]

| Turkic | |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Turkic peoples |

| Geographic distribution | West Asia Central Asia North Asia (Siberia) East Asia (Far East) Caucasus Eastern Europe |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Turkic |

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-5 | trk |

| Glottolog | turk1311[1] |

The distribution of the Turkic languages | |

Turkic languages are spoken as a native language by some 170 million people, and the total number of Turkic speakers, including second language speakers, is over 200 million.[5][6][7] The Turkic language with the greatest number of speakers is Turkish, spoken mainly in Anatolia and the Balkans; its native speakers account for about 40% of all Turkic speakers.[4]

Characteristic features such as vowel harmony, agglutination, and lack of grammatical gender, are universal within the Turkic family.[4]

“It seems strange that a language elaborated by the rude and nomad tribes of Central Asia,’’ wrote the British explorer Robert Barkley Shaw in his 1875 ‘‘Sketch of the Turki Language[8], ’’should present ... an example of symmetry such as few of the more cultivated forms of speech can boast”.

There is a high degree of mutual intelligibility among the various Oghuz languages, which include Turkish, Azerbaijani, Turkmen, Qashqai, Gagauz, Balkan Gagauz Turkish and Oghuz-influenced Crimean Tatar.[9] Although methods of classification vary, the Turkic languages are usually considered to be divided equally into two branches: Oghur, the only surviving member of which is Chuvash, and Common Turkic, which includes all other Turkic languages including the Oghuz subbranch.

Languages belonging to the Kipchak subbranch also share a high degree of mutual intelligibility among themselves. Qazaq and Qirghiz may be better seen a mutually intelligible dialects of a single tongue which are regarded as separate languages for sociopolitical reasons. They differ mainly phonetically while the lexicon and grammar are much the same, although both have standardized written forms that may differ in some ways. Until the 20th century, both languages used a common written form of Chaghatay Turki [10].

Turkic languages show some similarities with the Mongolic, Tungusic, Koreanic and Japonic languages. These similarities led some linguists to propose an Altaic language family, though this proposal is widely rejected by historical linguists.[11][12] Apparent similarities with the Uralic languages even caused these families to be regarded as one for a long time under the Ural-Altaic hypothesis.[13][14][15] However, there has not been sufficient evidence to conclude the existence of either of these macrofamilies, the shared characteristics between the languages being attributed presently to extensive prehistoric language contact.

Characteristics

Turkic languages are null-subject languages, have vowel harmony, extensive agglutination by means of suffixes and postpositions, and lack of grammatical articles, noun classes, and grammatical gender. Subject–object–verb word order is universal within the family. The root of a word is basically of one, two or three consonants.

History

Pre-history

The homeland of the Turkic peoples and their language is suggested to be somewhere between the Transcaspian steppe and Northeastern Asia (Manchuria),[16] with genetic evidence pointing to the region near South Siberia and Mongolia as the "Inner Asian Homeland" of the Turkic ethnicity.[17] Similarly several linguists, including Juha Janhunen, Roger Blench and Matthew Spriggs, suggest that modern-day Mongolia is the homeland of the early Turkic language.[18]

Extensive contact took place between Proto-Turks and Proto-Mongols approximately during the first millennium BC; the shared cultural tradition between the two Eurasian nomadic groups is called the "Turco-Mongol" tradition. The two groups shared a similar religion-system, Tengrism, and there exists a multitude of evident loanwords between Turkic languages and Mongolic languages. Although the loans were bidirectional, today Turkic loanwords constitute the largest foreign component in Mongolian vocabulary.[19]

Some lexical and extensive typological similarities between Turkic and the nearby Tungusic and Mongolic families, as well as the Korean and Japonic families (all formerly widely considered to be part of the so-called Altaic language family) has in more recent years been instead attributed to prehistoric contact amongst the group, sometimes referred to as the Northeast Asian sprachbund. A more recent (circa first millennium BCE) contact between "core Altaic" (Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic) is distinguished from this, due to the existence of definitive common words that appear to have been mostly borrowed from Turkic into Mongolic, and later from Mongolic into Tungusic, as Turkic borrowings into Mongolic significantly outnumber Mongolic borrowings into Turkic, and Turkic and Tungusic do not share any words that do not also exist in Mongolic.

Alexander Vovin (2004, 2010)[20][21] notes that Old Turkic had borrowed some words from the Ruan-ruan language (the language of the Rouran Khaganate), which Vovin considers to be an extinct non-Altaic language that is possibly a Yeniseian language or not related to any modern-day language.

Turkic languages also show some Chinese loanwords that point to early contact during the time of proto-Turkic.[22]

Robbeets (et al. 2015 and et al. 2017) suggest that the homeland of the Turkic languages was somewhere in Manchuria, close to the Mongolic, Tungusic and Koreanic homeland (including the ancestor of Japonic), and that these languages share a common "Transeurasian" origin.[23] More evidence for the proposed ancestral "Transeurasian" origin was presented by Nelson et al. 2020 and Li et al. 2020.[24][25]

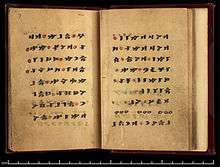

Early written records

The first established records of the Turkic languages are the eighth century AD Orkhon inscriptions by the Göktürks, recording the Old Turkic language, which were discovered in 1889 in the Orkhon Valley in Mongolia. The Compendium of the Turkic Dialects (Divânü Lügati't-Türk), written during the 11th century AD by Kaşgarlı Mahmud of the Kara-Khanid Khanate, constitutes an early linguistic treatment of the family. The Compendium is the first comprehensive dictionary of the Turkic languages and also includes the first known map of the Turkic speakers' geographical distribution. It mainly pertains to the Southwestern branch of the family.[26]

The Codex Cumanicus (12th–13th centuries AD) concerning the Northwestern branch is another early linguistic manual, between the Kipchak language and Latin, used by the Catholic missionaries sent to the Western Cumans inhabiting a region corresponding to present-day Hungary and Romania. The earliest records of the language spoken by Volga Bulgars, the parent to today's Chuvash language, are dated to the 13th–14th centuries AD.

Geographical expansion and development

With the Turkic expansion during the Early Middle Ages (c. 6th–11th centuries AD), Turkic languages, in the course of just a few centuries, spread across Central Asia, from Siberia to the Mediterranean. Various terminologies from the Turkic languages have passed into Persian, Hindustani, Russian, Chinese, and to a lesser extent, Arabic.[27]

The geographical distribution of Turkic-speaking peoples across Eurasia since the Ottoman era ranges from the North-East of Siberia to Turkey in the West.[28] (See picture in the box on the right above.)

For centuries, the Turkic-speaking peoples have migrated extensively and intermingled continuously, and their languages have been influenced mutually and through contact with the surrounding languages, especially the Iranian, Slavic, and Mongolic languages.[29]

This has obscured the historical developments within each language and/or language group, and as a result, there exist several systems to classify the Turkic languages. The modern genetic classification schemes for Turkic are still largely indebted to Samoilovich (1922).

The Turkic languages may be divided into six branches:[30]

- Common Turkic

- Southwestern (Oghuz Turkic)

- Southeastern (Karluk Turkic)

- Northwestern (Kipchak Turkic)

- Northeastern (Siberian Turkic)

- Arghu Turkic

- Oghur Turkic

In this classification, Oghur Turkic is also referred to as Lir-Turkic, and the other branches are subsumed under the title of Shaz-Turkic or Common Turkic. It is not clear when these two major types of Turkic can be assumed to have actually diverged.[31]

With less certainty, the Southwestern, Northwestern, Southeastern and Oghur groups may further be summarized as West Turkic, the Northeastern, Kyrgyz-Kipchak and Arghu (Khalaj) groups as East Turkic.[32]

Geographically and linguistically, the languages of the Northwestern and Southeastern subgroups belong to the central Turkic languages, while the Northeastern and Khalaj languages are the so-called peripheral languages.

Hruschka, et al. (2014)[33] use computational phylogenetic methods to calculate a tree of Turkic based on phonological sound changes.

Schema

The following isoglosses are traditionally used in the classification of the Turkic languages:[34][30]

- Rhotacism (or in some views, zetacism), e.g. in the last consonant of the word for "nine" *tokkuz. This separates the Oghur branch, which exhibits /r/, from the rest of Turkic, which exhibits /z/. In this case, rhotacism refers to the development of *-/r/, *-/z/, and *-/d/ to /r/,*-/k/,*-/kh/ in this branch.[35] See Antonov and Jacques (2012) [36] on the debate concerning rhotacism and lambdacism in Turkic.

- Intervocalic *d, e.g. the second consonant in the word for "foot" *hadaq

- Suffix-final -G, e.g. in the suffix *lIG, in e.g. *tāglïg

Additional isoglosses include:

- Preservation of word initial *h, e.g. in the word for "foot" *hadaq. This separates Khalaj as a peripheral language.

- Denasalisation of palatal *ń, e.g. in the word for "moon", *āń

*In the standard Istanbul dialect of Turkish, the ğ in dağ and dağlı is not realized as a consonant, but as a slight lengthening of the preceding vowel.

Members

The following table is based upon the classification scheme presented by Lars Johanson (1998)[37]

Vocabulary comparison

The following is a brief comparison of cognates among the basic vocabulary across the Turkic language family (about 60 words).

Empty cells do not necessarily imply that a particular language is lacking a word to describe the concept, but rather that the word for the concept in that language may be formed from another stem and is not a cognate with the other words in the row or that a loanword is used in its place.

Also, there may be shifts in the meaning from one language to another, and so the "Common meaning" given is only approximate. In some cases the form given is found only in some dialects of the language, or a loanword is much more common (e.g. in Turkish, the preferred word for "fire" is the Persian-derived ateş, whereas the native od is dead). Forms are given in native Latin orthographies unless otherwise noted.

| Common meaning | Proto-Turkic | Old Turkic | Turkish | Azerbaijani | Qashqai | Turkmen | Tatar | Bashkir | Kazakh | Kyrgyz | Uzbek | Uyghur | Sakha/Yakut | Chuvash | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | father, ancestor | *ata, *kaŋ | ata, apa, qaŋ | baba, ata | baba, ata | bowa/ata | ata | ata, atay | ata, atay | ata | ata | ota | ata | ağa | atte, aśu, aşşe |

| mother | *ana, *ög | ana, ög | ana, anne | ana | ana/nänä | ene | ana, äni | ana, inä(y)/asay | ana | ene | ona | ana | iye | anne, annü, amăşĕ | |

| son | *ogul | oɣul | oğul | oğul | oğul | ogul | ul | ul | ul | uul | oʻgʻil | oghul | uol | ıvăl, ul | |

| man | *ēr, *érkek | er | erkek | ər/erkək | kiši | erkek | ir | ir, irkäk | er, erkek | erkek | erkak | er | er | ar/arśın | |

| girl | *kï̄ŕ | qïz | kız | qız | qïz/qez | gyz | qız | qıð | qyz | kız | qiz | qiz | kııs | hĕr | |

| person | *kiĺi, *yạlaŋuk | kiši, yalaŋuq | kişi | kişi | kişi | keşe | keşe | kisi | kişi | kishi | kishi | kihi | śın | ||

| bride | *gélin | kelin | gelin | gəlin | gälin | gelin | kilen | kilen | kelin | kelin | kelin | kelin | kiyiit | kin | |

| mother-in-law | kaynana | qaynana | qäynänä | gaýyn ene | qayın ana | qäynä | qaıyn ene | kaynene | qaynona | qeyinana | huńama | ||||

| Body parts | heart | *yürek | yürek | yürek | ürək | iräg/üräg | ýürek | yöräk | yöräk | júrek | jürök | yurak | yürek | sürex | çĕre |

| blood | *kiān | qan | kan | qan | qan | gan | qan | qan | qan | kan | qon | qan | xaan | yun | |

| head | *baĺč | baš | baş | baş | baš | baş | baş | baş | bas | baş | bosh | bash | bas | puś/poś | |

| hair | *s(i)ač, *kïl | sač, qïl | saç, kıl | saç, qıl | tik/qel | saç, gyl | çäç, qıl | säs, qıl | shash, qyl | çaç, kıl | soch, qil | sach, qil | battax, kıl | śüś, hul | |

| eye | *göŕ | köz | göz | göz | gez/göz | göz | küz | küð | kóz | köz | koʻz | köz | xarax, kös | kuś/koś | |

| eyelash | *kirpik | kirpik | kirpik | kirpik | kirpig | kirpik | kerfek | kerpek | kirpik | kirpik | kiprik | kirpik | kılaman, kirbii | hărpăk | |

| ear | *kulkak | qulqaq | kulak | qulaq | qulaq | gulak | qolaq | qolaq | qulaq | kulak | quloq | qulaq | kulgaax | hălha | |

| nose | *burun | burun | burun | burun | burn | burun | borın | moron | muryn | murun | burun | burun | murun, munnu | ||

| arm | *kol | qol | kol | qol | qol | gol | qul | qul | qol | kol | qoʻl | qol | хol | hul | |

| hand | *el-ig | elig | el | əl | äl | el | alaqan | alakan | ilik | ilii | ală | ||||

| finger | *erŋek, *biarŋak | erŋek | parmak | barmaq | burmaq | barmaq | barmaq | barmaq | barmaq | barmak | barmoq | barmaq | tarbaq | pürne/porńa | |

| fingernail | *dïrŋak | tïrŋaq | tırnak | dırnaq | dïrnaq | dyrnak | tırnaq | tırnaq | tyrnaq | tırmak | tirnoq | tirnaq | tıngıraq | çĕrne | |

| knee | *dīŕ, *dǖŕ | tiz | diz | diz | diz | dyz | tez | teð | tize | tize | tizza | tiz | tobuk | çĕrśi, çerkuśśi | |

| calf | *baltïr | baltïr | baldır | baldır | ballïr | baldyr | baltır | baltır | baltyr | baltır | boldir | baldir | ballır | pıl | |

| foot | *(h)adak | adaq | ayak | ayaq | ayaq | aýak | ayaq | ayaq | aıaq | ayak | oyoq | ayaq | ataq | ura | |

| belly | *kạrïn | qarïn | karın | qarın | qarn | garyn | qarın | qarın | qaryn | karın | qorin | qerin | xarın | hırăm | |

| Animals | horse | *(h)at | at | at | at | at | at | at | at | at | at | ot | at | at | ut/ot |

| cattle | *dabar | ingek, tabar | inek, davar, sığır | inək, sığır | seğer | sygyr | sıyır | hıyır | sıyr | sıyır | sigir | siyir | ınax | ĕne | |

| dog | *ït, *köpek | ït | it, köpek | it | kepäg | it | et | et | ıt | it | it | it | ıt | yıtă | |

| fish | *bālïk | balïq | balık | balıq | balïq | balyk | balıq | balıq | balyq | balık | baliq | beliq | balık | pulă | |

| louse | *bït | bit | bit | bit | bit | bit | bet | bet | bıt | bit | bit | bit | bıt | pıytă/puťă | |

| Other nouns | house | *eb, *bark | eb, barq | ev, bark | ev | äv | öý | öy | öy | úı | üy | uy | öy | śurt | |

| tent | *otag, *gerekü | otaɣ, kerekü | çadır, otağ | çadır; otaq | čador | çadyr; otag | çatır | satır | shatyr; otaý | çatır | chodir; oʻtoq | chadir; otaq | otuu | çatăr | |

| way | *yōl | yol | yol | yol | yol | ýol | yul | yul | jol | jol | yoʻl | yol | suol | śul | |

| bridge | *köprüg | köprüg | köprü | körpü | köpri | küper | küper | kópir | köpürö | koʻprik | kövrük | kürpe | kĕper | ||

| arrow | *ok | oq | ok | ox | ox/tir | ok | uq | uq | oq | ok | oʻq | oq | ox | uhă | |

| fire | *ōt | ōt | od, ateş (Pers.) | od | ot | ot | ut | ut | ot | ot | oʻt | ot | uot | vut/vot | |

| ash | *kül | kül | kül | kül | kil/kül | kül | köl | köl | kúl | kül | kul | kül | kül | kĕl | |

| water | *sub, *sïb | sub | su | su | su | suw | su | hıw | sý | suu | suv | su | uu | şıv/şu | |

| ship, boat | *gḗmi | kemi | gemi | gəmi | gämi | köymä | kämä | keme | keme | kema | keme | kimĕ | |||

| lake | *kȫl | köl | göl | göl | göl/gel | köl | kül | kül | kól | köl | koʻl | köl | küöl | külĕ | |

| sun/day | *güneĺ, *gün | kün | güneş, gün | günəş, gün | gin/gün | gün | qoyaş, kön | qoyaş, kön | kún | kün | quyosh, kun | quyash, kün | kün | hĕvel, kun | |

| cloud | *bulït | bulut | bulut | bulud | bulut | bulut | bolıt | bolot | bult | bulut | bulut | bulut | bılıt | pĕlĕt | |

| star | *yultuŕ | yultuz | yıldız | ulduz | ulluz | ýyldyz | yoldız | yondoð | juldyz | jıldız | yulduz | yultuz | sulus | śăltăr | |

| ground, earth | *toprak | topraq | toprak | torpaq | torpaq | toprak | tufraq | tupraq | topyraq | topurak | tuproq | tupraq | toburax | tăpra | |

| hilltop | *tepö, *töpö | töpü | tepe | təpə | depe | tübä | tübä | tóbe | töbö | tepa | töpe | töbö | tüpĕ | ||

| tree/wood | *ïgač | ïɣač | ağaç | ağac | ağaĵ | agaç | ağaç | ağas | aǵash | jygaç | yogʻoch | yahach | yıvăś | ||

| god (Tengri) | *teŋri, *taŋrï | teŋri, burqan | tanrı | tanrı | tarï/Allah/Xoda | taňry | täñre | täñre | táńiri | teñir | tangri | tengri | tangara | tură/toră | |

| sky | *teŋri, *kȫk | kök, teŋri | gök | göy | gey/göy | gök | kük | kük | kók | kök | koʻk | kök | küöx | kăvak/koak | |

| Adjectives | long | *uŕïn | uzun | uzun | uzun | uzun | uzyn | ozın | oðon | uzyn | uzun | uzun | uzun | uhun | vărăm |

| new | *yaŋï, *yeŋi | yaŋï | yeni | yeni | yeŋi | ýaňy | yaña | yañı | jańa | jañı | yangi | yengi | saña | śĕnĕ | |

| fat | *semiŕ | semiz | semiz, şişman | kök | semiz | simez | himeð | semiz | semiz | semiz | semiz | emis | samăr | ||

| full | *dōlï | tolu | dolu | dolu | dolu | doly | tulı | tulı | toly | tolo | toʻla | toluq | toloru | tulli | |

| white | *āk, *ürüŋ | āq, ürüŋ | ak, beyaz (Ar.) | ağ | aq | ak | aq | aq | aq | ak | oq | aq | şură | ||

| black | *kara | qara | kara, siyah (Pers.) | qara | qärä | gara | qara | qara | qara | kara | qora | qara | xara | hura, hora | |

| red | *kïŕïl | qïzïl | kızıl, kırmızı (Ar.) | qızıl | qïzïl | gyzyl | qızıl | qıðıl | qyzyl | kızıl | qizil | qizil | kıhıl | hĕrlĕ | |

| Numbers | 1 | *bīr | bir | bir | bir | bir | bir | ber | ber | bir | bir | bir | bir | biir | pĕrre |

| 2 | *éki | eki | iki | iki | ikki | iki | ike | ike | eki | eki | ikki | ikki | ikki | ikkĕ | |

| 4 | *dȫrt | tört | dört | dörd | derd/dörd | dört | dürt | dürt | tórt | tört | toʻrt | tört | tüört | tăvattă | |

| 7 | *yéti | yeti | yedi | yeddi | yeddi | ýedi | cide | yete | jeti | jeti | yetti | yetti | sette | śiççe | |

| 10 | *ōn | on | on | on | on | on | un | un | on | on | oʻn | on | uon | vunnă, vună, vun | |

| 100 | *yǖŕ | yüz | yüz | yüz | iz/yüz | ýüz | yöz | yöð | júz | jüz | yuz | yüz | süüs | śĕr | |

| Proto-Turkic | Old Turkic | Turkish | Azerbaijani | Qashqai | Turkmen | Tatar | Bashkir | Kazakh | Kyrgyz | Uzbek | Uyghur | Sakha/Yakut | Chuvash |

Other possible relations

The Turkic language family is currently regarded as one of the world's primary language families.[14] Turkic is one of the main members of the controversial Altaic language family. There are some other theories about an external relationship but none of them are generally accepted.

Korean

The possibility of a genetic relation between Turkic and Korean, independently from Altaic, is suggested by some linguists.[45][46][47] The linguist Kabak (2004) of the University of Würzburg states that Turkic and Korean share similar phonology as well as morphology. Yong-Sŏng Li (2014)[46] suggest that there are several cognates between Turkic and Old Korean. He states that these supposed cognates can be useful to reconstruct the early Turkic language. According to him, words related to nature, earth and ruling but especially to the sky and stars seem to be cognates.

The linguist Choi[47] suggested already in 1996 a close relationship between Turkic and Korean regardless of any Altaic connections:

In addition, the fact that the morphological elements are not easily borrowed between languages, added to the fact that the common morphological elements between Korean and Turkic are not less numerous than between Turkic and other Altaic languages, strengthens the possibility that there is a close genetic affinity between Korean and Turkic.

— Choi Han-Woo, A Comparative Study of Korean and Turkic (Hoseo University)

Many historians also point out a close non-linguistic relationship between Turkic peoples and Koreans.[48] Especially close were the relations between the Göktürks and Goguryeo.[49]

Rejected or controversial theories

Uralic

Some linguists suggested a relation to Uralic languages, especially to the Ugric languages. This view is rejected and seen as obsolete by mainstream linguists. Similarities are because of language contact and borrowings mostly from Turkic into Ugric languages. Stachowski (2015) states that any relation between Turkic and Uralic must be a contact one.[50]

See also

- Altaic languages

- List of Turkic languages

- List of Ukrainian words of Turkic origin

- Middle Turkic

- Old Turkic alphabet

- Old Turkic language

- Proto-Turkic language

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Turkic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Dybo A.V. (2007). "ХРОНОЛОГИЯ ТЮРКСКИХ ЯЗЫКОВ И ЛИНГВИСТИЧЕСКИЕ КОНТАКТЫ РАННИХ ТЮРКОВ" [Chronology of Turkish Languages and Linguistic Contacts of Early Turks] (PDF) (in Russian). p. 766. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2005. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Janhunen, Juha (2013). "Personal pronouns in Core Altaic". In Martine Irma Robbeets; Hubert Cuyckens (eds.). Shared Grammaticalization: With Special Focus on the Transeurasian Languages. p. 223.

- Katzner, Kenneth (March 2002). Languages of the World, Third Edition. Routledge, an imprint of Taylor & Francis Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-415-25004-7.

- Brigitte Moser, Michael Wilhelm Weithmann, Landeskunde Türkei: Geschichte, Gesellschaft und Kultur, Buske Publishing, 2008, p.173

- Deutsches Orient-Institut, Orient, Vol. 41, Alfred Röper Publushing, 2000, p.611

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Shaw, Robert (1878). A Sketch of the Turki Language as Spoken in Eastern Turkistan (Kashgar and Yarkand): Grammar [including 21 p. of Extracts in Turkish. Baptist Mission Press.

- "Language Materials Project: Turkish". UCLA International Institute, Center for World Languages. February 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- Robert Lindsay. "Mutual Intelligibility Among the Turkic Languages". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Vovin, Alexander (2005). "The end of the Altaic controversy: In memory of Gerhard Doerfer". Central Asiatic Journal. 49 (1): 71–132. JSTOR 41928378.

- Georg, Stefan; Michalove, Peter A.; Ramer, Alexis Manaster; Sidwell, Paul J. (1999). "Telling general linguists about Altaic". Journal of Linguistics. 35 (1): 65–98. JSTOR 4176504.

- Sinor, 1988, p.710

- George van DRIEM: Handbuch der Orientalistik. Volume 1 Part 10. BRILL 2001. Page 336

- M. A. Castrén, Nordische Reisen und Forschungen. V, St.-Petersburg, 1849

- Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; et al. (21 April 2015). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLoS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

The origin and early dispersal history of the Turkic peoples is disputed, with candidates for their ancient homeland ranging from the Transcaspian steppe to Manchuria in Northeast Asia,

- Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; et al. (21 April 2015). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLoS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

Thus, our study provides the first genetic evidence supporting one of the previously hypothesized IAHs to be near Mongolia and South Siberia.

- Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (2003). Archaeology and Language II: Archaeological Data and Linguistic Hypotheses. Routledge. p. 203. ISBN 9781134828692.

- Clark, Larry V. (1980). "Turkic Loanwords in Mongol, I: The Treatment of Non-initial S, Z, Š, Č". Central Asiatic Journal. 24 (1/2): 36–59. JSTOR 41927278.

- Vovin, Alexander 2004. 'Some Thoughts on the Origins of the Old Turkic 12-Year Animal Cycle.' Central Asiatic Journal 48/1: 118–32.

- Vovin, Alexander. 2010. Once Again on the Ruan-ruan Language. Ötüken’den İstanbul’a Türkçenin 1290 Yılı (720–2010) Sempozyumu From Ötüken to Istanbul, 1290 Years of Turkish (720–2010). 3–5 Aralık 2010, İstanbul / 3–5 December 2010, İstanbul: 1–10.

- Johanson, Lars; Johanson, Éva Ágnes Csató (29 April 2015). The Turkic Languages. Routledge. ISBN 9781136825279.

- Robbeets, Martine (2017). "Transeurasian: A case of farming/language dispersal". Language Dynamics and Change. 7 (2): 210–251. doi:10.1163/22105832-00702005.

- Nelson, Sarah. "Tracing population movements in ancient East Asia through the linguistics and archaeology of textile production" (PDF). Cambridge University. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Li, Tao. "Millet agriculture dispersed from Northeast China to the Russian Far East: Integrating archaeology, genetics, and linguistics". Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Soucek, Svat (March 2000). A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65169-1.

- Findley, Carter V. (October 2004). The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517726-8.

- Turkic Language tree entries provide the information on the Turkic-speaking regions.

- Johanson, Lars (2001). "Discoveries on the Turkic linguistic map" (PDF). Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul. Retrieved 18 March 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Lars Johanson, The History of Turkic. In Lars Johanson & Éva Ágnes Csató (eds), The Turkic Languages, London, New York: Routledge, 81–125, 1998.Classification of Turkic languages

- See the main article on Lir-Turkic.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Language Family Trees – Turkic". Retrieved 18 March 2007.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) The reliability of Ethnologue lies mainly in its statistics whereas its framework for the internal classification of Turkic is still based largely on Baskakov (1962) and the collective work in Deny et al. (1959–1964). A more up to date alternative to classifying these languages on internal camparative grounds is to be found in the work of Johanson and his co-workers.

- Hruschka, Daniel J.; Branford, Simon; Smith, Eric D.; Wilkins, Jon; Meade, Andrew; Pagel, Mark; Bhattacharya, Tanmoy (2015). "Detecting Regular Sound Changes in Linguistics as Events of Concerted Evolution 10.1016/j.cub.2014.10.064". Current Biology. 25 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.10.064. PMC 4291143. PMID 25532895.

- Самойлович, А. Н. (1922). Некоторые дополнения к классификации турецких языков (in Russian).

- Larry Clark, "Chuvash", in The Turkic Languages, eds. Lars Johanson & Éva Ágnes Csató (London–NY: Routledge, 2006), 434–452.

- Anton Antonov & Guillaume Jacques, "Turkic kümüš ‘silver’ and the lambdaism vs sigmatism debate", Turkic Languages 15, no. 2 (2012): 151–70.

- Lars Johanson (1998) The History of Turkic. In Lars Johanson & Éva Ágnes Csató (eds) The Turkic Languages. London, New York: Routledge, 81–125.

- Deviating. Historically developed from Southwestern (Oghuz) (Johanson 1998)

- "turcologica". Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Tura, Baraba, Tomsk, Tümen, Ishim, Irtysh, Tobol, Tara, etc. are partly of different origin (Johanson 1998)

- Aini contains a very large Persian vocabulary component, and is spoken exclusively by adult men, almost as a cryptolect.

- Coene 2009, p. 75

- Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Contributors Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie (revised ed.). Elsevier. 2010. p. 1109. ISBN 978-0080877754. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: others (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johanson, Lars, ed. (1998). The Mainz Meeting: Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Turkish Linguistics, August 3–6, 1994. Turcologica Series. Contributor Éva Ágnes Csató. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 28. ISBN 978-3447038645. Retrieved 24 April 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sibata, Takesi (1979). "Some syntactic similarities between Turkish, Korean, and Japanese". Central Asiatic Journal. 23 (3/4): 293–296. ISSN 0008-9192. JSTOR 41927271.

- SOME STAR NAMES IN MODERN TURKIC LANGUAGES-I - Yong-Sŏng LI - Academy of Korean Studies Grant funded by the Korean Government (MEST) (AKS-2010-AGC-2101) - Seoul National University 2014

- Choi, Han-Woo (1996). "A comparative study of Korean and Turkic: Is Korean Altaic?" (PDF). International Journal of Central Asian Studies. 1.

- Babayar, Gaybullah (2004). "On the ancient relations between the Turkic and Korean peoples" (PDF). Journal of Turkic Civilization Studies (1): 151–155.

- Tae-Don, Noh (2016). "Relations between ancient Korea and Turkey: An examination of contacts between Koguryŏ and the Turkic Khaganate". Seoul Journal of Korean Studies. 29 (2): 361–369. doi:10.1353/seo.2016.0017. ISSN 2331-4826.

- Stachowski, Marek (2015). "Turkic pronouns against a Uralic background". Iran and the Caucasus. 19 (1): 79–86. ISSN 1609-8498.

Further reading

- Akhatov G. Kh. 1960. "About the stress in the language of the Siberian Tatars in connection with the stress of modern Tatar literary language" .- Sat *"Problems of Turkic and the history of Russian Oriental Studies." Kazan. (in Russian)

- Akhatov G.Kh. 1963. "Dialect West Siberian Tatars" (monograph). Ufa. (in Russian)

- Baskakov, N.A. 1962, 1969. Introduction to the study of the Turkic languages. Moscow. (in Russian)

- Boeschoten, Hendrik & Lars Johanson. 2006. Turkic languages in contact. Turcologica, Bd. 61. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-447-05212-0

- Clausen, Gerard. 1972. An etymological dictionary of pre-thirteenth-century Turkish. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Deny, Jean et al. 1959–1964. Philologiae Turcicae Fundamenta. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Dolatkhah, Sohrab. 2016. Parlons qashqay. In: collection "parlons". Paris: L'Harmattan.

- Dolatkhah, Sohrab. 2016. Le qashqay: langue turcique d'Iran. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (online).

- Dolatkhah, Sohrab. 2015. Qashqay Folktales. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (online).

- Johanson, Lars & Éva Agnes Csató (ed.). 1998. The Turkic languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-08200-5.

- Johanson, Lars. 1998. "The history of Turkic." In: Johanson & Csató, pp. 81–125.

- Johanson, Lars. 1998. "Turkic languages." In: Encyclopædia Britannica. CD 98. Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 5 sept. 2007.

- Menges, K. H. 1968. The Turkic languages and peoples: An introduction to Turkic studies. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Öztopçu, Kurtuluş. 1996. Dictionary of the Turkic languages: English, Azerbaijani, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tatar, Turkish, Turkmen, Uighur, Uzbek. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14198-2

- Samoilovich, A. N. 1922. Some additions to the classification of the Turkish languages. Petrograd.

- Savelyev, Alexander and Martine Robbeets. (2019). lexibank/savelyevturkic: Turkic Basic Vocabulary Database (Version v1.0) [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3556518

- Schönig, Claus. 1997–1998. "A new attempt to classify the Turkic languages I-III." Turkic Languages 1:1.117–133, 1:2.262–277, 2:1.130–151.

- Starostin, Sergei A., Anna V. Dybo, and Oleg A. Mudrak. 2003. Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-13153-1

- Voegelin, C.F. & F.M. Voegelin. 1977. Classification and index of the World's languages. New York: Elsevier.

External links

- Turkic Languages Verb Comparison

- Turkic Inscriptions of Orkhon Valley, Mongolia

- Turkic Languages: Resources – University of Michigan

- Map of Turkic languages

- Classification of Turkic Languages

- Online Uyghur–English Dictionary

- Turkic languages at Curlie

- Turkic language vocabulary comparison tool / dictionary

- A Comparative Dictionary of Turkic Languages Open Project

- The Turkic Languages in a Nutshell with illustrations.

- Swadesh lists of Turkic basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Turkic basic vocabularies

- Conferences on Turkic languages processing: Astana, Kazakhstan, 2013, Istanbul, Turkey, 2014, Kazan, Tatarstan, 2015