Kyrgyz people

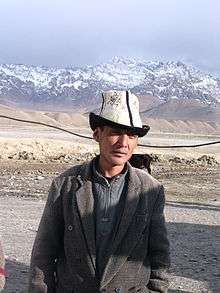

The Kyrgyz people (also spelled Kyrghyz and Kirghiz) are a Turkic ethnic group native to Central Asia, primarily Kyrgyzstan.

Кыргыздар Kırğızdar قىرغىزدار | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 5 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 4,587,430[a][1][2] | |

| 250,000[3] | |

| 202,500[4] | |

| 103,422[5] | |

| 62,000 | |

| 23,274[6] | |

| 1,600 | |

| 1,130[7] | |

| 1,128[8] | |

| Languages | |

| Kyrgyz (L1) Russian and Chinese (L2) | |

| Religion | |

Predominantly Sunni Islam[9][10]

| |

^a At the 2009 census, ethnic Kyrgyz constituted roughly 71% of population of Kyrgyzstan (5.36 million). | |

Etymology

There are several theories on the origin of ethnonym Kyrgyz. It is often said to be derived from the Turkic word kyrk ("forty"), with -iz being an old plural suffix, so Kyrgyz literally means "a collection of forty tribes".[15] It also means "imperishable", "inextinguishable", "immortal", "unconquerable" or "unbeatable", as well as its association with the epic hero Manas, who – according to a founding myth – unified the 40 tribes against the Khitans. A rival myth, recorded in 1370 in the History of Yuan, concerns 40 women born on a steppe motherland.[16]

.jpg)

The earliest records of the ethnonym appear to have been the transcriptions: Gekun (鬲昆, Old Chinese: *k.reg-ku:n) and Jiankun (堅昆, OC: *ki:n-ku:n); these suggest that the original ethnonym was *kirkur ~ kirgur and/or *kirkün; possibly meaning "field people", "field Huns" (渾).[17] Another transcription Jiegu (結骨, EMC: *kέt-kwət) suggests *kirkut / kirgut. Besides, Chinese scholars later used a number of different transcriptions for the Kyrgyz people: these include Hegu, Hegusi, and Juwu, then to Xiajiasi during the reign of Emperor Wuzong during the Tang dynasty. Xiajiasi is said to mean "yellow head and red face".[18] By the time of the Mongol Empire, the meaning of the word *kirkun had apparently been forgotten – as was shown by variations in readings of it across different reductions of the History of Yuan. This may have led to the adoption of Kyrgyz and its mythical explanation.

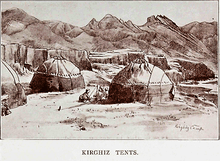

During the 18th and 19th centuries, European writers used the early Romanized form Kirghiz – from the contemporary Russian киргизы – to refer not only to the modern Kyrgyz, but also to their more numerous northern relatives, the Kazakhs. When distinction had to be made, more specific terms were used: the Kyrgyz proper were known as the Kara-Kirghiz ("Black Kirghiz", from the colour of their tents),[19] and the Kazakhs were named the Kaisaks.[20][21] or "Kirghiz-Kazaks".[19]

Origins

The early Kyrgyz people, known as Yenisei Kyrgyz, have their origins in the western parts of modern-day Mongolia and first appear in written records in the Chinese annals of the Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian (compiled 109 BC to 91 BC), as Gekun (鬲昆, 隔昆) or Jiankun (堅昆). The early inhabitants of modern Kyrgyzstan were described in Tang Dynasty texts as having "red hair and green eyes" while those with dark hair and eyes were said to be descendants of a Chinese general Li Ling.[18] In Chinese sources, these tribes were described as fair-skinned, green- or blue-eyed and red-haired people with a mixture of European and East Asian features. The Middle Age Chinese composition Tanghuiyao of the 8–10th century transcribed the name "Kyrgyz" as Jiegu (Kirgut), and their tamga was depicted as identical to the tamga of present-day Kyrgyz tribes Azyk, Bugu, Cherik, Sary Bagysh and few others.[22]

According to recent historical findings, Kyrgyz history dates back to 201 BC.[23] The Yenisei Kyrgyz lived in the upper Yenisey River valley, central Siberia. In Late Antiquity the Yenisei Kyrgyz were a part of the Tiele people. Later, in the Early Middle Ages, the Yenisei Kyrgyz were a part of the confederations of the Göktürk and Uyghur Khaganates.

In 840 a revolt led by the Yenisei Kyrgyz brought down the Uyghur Khaganate, and brought the Yenisei Kyrgyz to a dominating position in the former Second Turkic Khaganate. With the rise to power, the center of the Kyrgyz Khaganate moved to Jeti-su, and brought about a spread south of the Kyrgyz people, to reach Tian Shan mountains and Xinjiang, bringing them into contact with the existing peoples of western China, especially Tibet.

By the 16th century the carriers of the ethnonym Kirgiz lived in South Siberia, Xinjiang, Tian Shan, Pamir-Alay, Middle Asia, Urals (among Bashkirs), in Kazakhstan.[24] In the Tian Shan and Xinjiang area, the term Kyrgyz retained its unifying political designation, and became a general ethnonym for the Yenisei Kirgizes and aboriginal Turkic tribes that presently constitute the Kyrgyz population.[25] Though it is obviously impossible to directly identify the Yenisei and Tien Shan Kyrgyz, a trace of their ethnogenetical connections is apparent in archaeology, history, language and ethnography. A majority of modern researchers came to the conclusion that the ancestors of Kyrgyz tribes had their origin in the most ancient tribal unions of Sakas/Scythians, Wusun/Issedones, Dingling, Mongols and Huns.[26]

Also, there follow from the oldest notes about the Kyrgyz that the definite mention of Kyrgyz ethnonym originates from the 6th century. There is certain probability that there was relation between Kyrgyz and Gegunese already in the 2nd century BC, next, between Kyrgyz and Khakases since the 6th century A.D., but there is quite missing a unique mention. The Kyrgyz as ethnic group are mentioned quite unambiguously in the time of Genghis Khan rule (1162–1227), when their name replaces the former name Khakas.[27]

Genetics

The genetic makeup of the Kyrgyz is consistent with their origin as a mix of tribes.[28][29] For instance, 63% of modern Kyrgyz men of Jumgal District[30] are Haplogroup R1a1 (Y-DNA). Low diversity of Kyrgyz R1a1 indicates a founder effect within the historical period.[31] Haplogroup R1a1 (Y-DNA) is often believed to be a marker of the Proto-Indo-European language speakers.[28][31][32][33] Other groups of Kyrgyz show considerably lower haplogroup R frequencies and almost lack haplogroup N.[34] (except for the Kyrgyz from Pamir[35])

Di Cristofaro et al. (2013) reported the results of analysis of the Y-DNA of 132 Kyrgyz individuals from Kyrgyzstan (40 from Central Kyrgyzstan, 37 from Northwest Kyrgyzstan, 35 from East Kyrgyzstan, and 20 from Southwest Kyrgyzstan), finding that they belonged to haplogroup R (78/132 = 59.1%, including 72/132 = 54.5% R1a-M198/M17, 3/132 = 2.3% R1b-L23(xU106, S116, U152), 2/132 = 1.5% R1b-M478/M73, and 1/132 = 0.76% R-M207(xR1a-SRY1532.2, R1b-M343, R2-M479)), haplogroup C2-M217 (26/132 = 19.7%, including 11/132 = 8.3% C-M401, 7/132 = 5.3% C-M532(xM86, M504, M546, M401), 7/132 = 5.3% C-M86, and 1/132 = 0.76% C-M386/PK2(xM407, M532)), haplogroup O (8/132 = 6.1%, including 5/132 = 3.8% O-M134(xM117), 2/132 = 1.5% O-M122(xKL2, P201), and 1/132 = 0.76% O-M95), haplogroup J (7/132 = 5.3%, including 2/132 = 1.5% J2a-P55(xM530, M322, M67), 1/132 = 0.76% J2a-M410(xP55), 1/132 = 0.76% J2a-M67(xM92), 1/132 = 0.76% J2b-M241, 1/132 = 0.76% J1-Page8, and 1/132 = 0.76% J1-M267(xPage8, short DYS388)), haplogroup N (6/132 = 4.5%, including 5/132 = 3.8% N-M231(xP43, Tat) and 1/132 = 0.76% N-P43), haplogroup G (2/132 = 1.5%, including 1/132 = 0.76% G2a-P16 and 1/132 = 0.76% G2a-P303), haplogroup L (2/132 = 1.5%, including 1/132 = 0.76% L-M76 and 1/132 = 0.76% L-M357), haplogroup E-M81 (1/132 = 0.76%), haplogroup H-M82 (1/132 = 0.76%), and haplogroup Q-M346 (1/132 = 0.76%).[36]

Depending on the geographical location of samples, West Eurasian mtDNA haplogroup lineages make up 27% to 42.6% in the Kyrgyz.[37] The majority of Kyrgyz belong to East Eurasian mtDNA haplogroups, with Haplogroup mtDNA D being the most frequent lineage.[37]

According to a genetic study based on geographic location of the 26 Central Asian populations shows the admixture proportions of East Eurasian ancestry is predominant in most Kyrgyz living in Kyrgyzstan. East Eurasian ancestry makes up roughly two-thirds with exceptions of Kyrgyz living in Tajikistan and the western areas of Kyrgyzstan where it forms only half.[38]

Political development

The Kyrgyz state reached its greatest extent after defeating the Uyghur Khaganate in 840 AD, in alliance with the Chinese Tang dynasty.

The Kirghiz khagans of the Yenisei Kirghiz Khaganate claimed descent from the Han Chinese general Li Ling, which was mentioned in the diplomatic correspondence between the Kirghiz khagan and the Tang Dynasty emperor, since the Tang imperial Li family claimed descent from Li Ling's grandfather, Li Guang. The Kirghiz qaghan assisted the Tang dynasty in destroying the Uyghur Khaganate and rescuing the Princess Taihe from the Uyghurs. They also killed a Uyghur khagan in the process.

Then Kyrgyz quickly moved as far as the Tian Shan range and maintained their dominance over this territory for about 200 years. In the 12th century, however, Kyrgyz domination had shrunk to the Altai and Sayan Mountains as a result of Mongol expansion. With the rise of the Mongol Empire in the 13th century, the Kyrgyz migrated south. In 1207, after the establishment of Yekhe Mongol Ulus (Mongol empire), Genghis Khan's oldest son Jochi occupied Kyrgyzstan without resistance. The state remained a Mongol vassal until the late 14th century.

Various Turkic peoples ruled them until 1685, when they came under the control of the Oirats (Dzungars).

Religion

Kyrgyz are predominantly Muslims of the Hanafi Sunni school.[39] Islam was first introduced by Arab traders who travelled along the Silk Road in the seventh and eighth centuries. In the 8th century, orthodox Islam reached the Fergana valley with the Uzbeks. However, in the tenth-century Persian text Hudud al-'alam, the Kyrgyz was still described as a people who "venerate the Fire and burn the dead".[40]

The Kyrgyz began to convert to Islam in the mid-seventeenth century. Sufi missionaries played an important role in the conversion. By the 19th century, the Kyrgyz were considered devout Muslims and some performed the Hajj.[41]

Atheism has some following in the northern regions under Russian communist influence. As of today, few cultural rituals of Shamanism are still practiced alongside Islam, particularly in Central Kyrgyzstan. During a July 2007 interview, Bermet Akayeva, the daughter of Askar Akayev, the former President of Kyrgyzstan, stated that Islam is increasingly taking root, even in the northern portion which came under communist influence.[42] She emphasized that many mosques have been built and that the Kyrgyz are "increasingly devoting themselves to Islam".[43]

Many ancient indigenous beliefs and practices, including shamanism and totemism, coexisted syncretically with Islam. Shamans, most of whom are women, still play a prominent role at funerals, memorials, and other ceremonies and rituals. This split between the northern and southern Kyrgyz in their religious adherence to Muslim practices can still be seen today. Likewise, the Sufi order of Islam has been one of the most active Muslim groups in Kyrgyzstan for over a century.

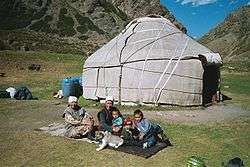

In Afghanistan

The Kyrgyz population of Afghanistan was 1,130 in 2003, all from eastern Wakhan District[44] in the Badakhshan Province of northeastern Afghanistan.[7] They still lead a nomadic lifestyle and are led by a khan or tekin.

The suppression of the 1916 rebellion against Russian rule in Central Asia caused many Kyrgyz later to migrate to China and Afghanistan. Most of the Kyrgyz refugees in Afghanistan settled in the Wakhan region. Until 1978, the northeastern portion of Wakhan was home to about 3–5 thousand ethnic Kyrgyz.[45][46] In 1978, most Kyrgyz inhabitants fled to Pakistan in the aftermath of the Saur Revolution. They requested 5,000 visas from the United States consulate in Peshawar for resettlement in Alaska, a state of the United States which they thought might have a similar climate and temperature with the Wakhan Corridor. Their request was denied. In the meantime, the heat and the unsanitary conditions of the refugee camp were killing off the Kyrgyz refugees at an alarming rate. Turkey, which was under the military coup rule of General Kenan Evren, stepped in, and resettled the entire group in the Lake Van region of Turkey in 1982. The village of Ulupamir (or “Great Pamir” in Kyrgyz) in Erciş in Van Province was given to these, where more than 5,000 of them still reside today. The documentary film 37 Uses for a Dead Sheep – the Story of the Pamir Kirghiz was based on the life of these Kyrgyz in their new home.[47][48] Some Kyrgyz returned to Wakhan in October 1979, following the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.[49] They are found around the Little Pamir.[50]

In China

The Kyrgyz form one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by the People's Republic of China. There are more than 145,000 Kyrgyz in China. They are known in China as Kēěrkèzī zú (simplified Chinese: 柯尔克孜族; traditional Chinese: 柯爾克孜族).[51]

In the 19th century, Russian settlers on traditional Kirghiz land drove a lot of the Kirghiz over the border to China, causing their population to increase in China.[52] Compared to Russian controlled areas, more benefits were given to the Muslim Kirghiz on the Chinese controlled areas. Russian settlers fought against the Muslim nomadic Kirghiz, which led the Russians to believe that the Kirghiz would be a liability in any conflict against China. The Muslim Kirghiz were sure that in an upcoming war, that China would defeat Russia.[53]

The Kirghiz of Xinjiang revolted in the 1932 Kirghiz rebellion, and also participated in the Battle of Kashgar (1933) and again in 1934.[54]

They are found mainly in the Kizilsu Kirghiz Autonomous Prefecture in the southwestern part of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, with a smaller remainder found in the neighboring Wushi (Uqturpan), Aksu, Shache (Yarkand), Yingisar, Taxkorgan and Pishan (Guma), and in Tekes, Zhaosu (Monggolkure), Emin (Dorbiljin), Bole (Bortala), Jinghev (Jing) and Gongliu County in northern Xinjiang.[55]

A peculiar group, also included under the "Kyrgyz nationality" by the PRC official classification, are the so-called "Fuyu Kyrgyz". It is a group of several hundred Yenisei Kirghiz (Khakas people) people whose forefathers were relocated from the Yenisei river region to Dzungaria by the Dzungar Khanate in the 17th century, and upon defeat of the Dzungars by the Qing dynasty, they were relocated from Dzungaria to Manchuria in the 18th century, and who now live in Wujiazi Village in Fuyu County, Heilongjiang Province. Their language (the Fuyü Gïrgïs dialect) is related to the Khakas language.[56]

Certain segments of the Kyrgyz in China are followers of Tibetan Buddhism.[11][12][57][58][59][60]

Notable Kyrgyz people

- Asylgul Abdurekhmenova - politician

- Chinghiz Aitmatov – author

- Kasym Tynystanov – a prominent Kyrgyz scientist, politician and poet, first minister of education

- Bubusara Beishenalieva – ballet dancer

- Askar Akayev – politician, scientist, first President of Kyrgyzstan

- Kurmanjan Datka – politician, former statesman

- Abdylas Maldybaev – actor/musician

- Ulan Melisbek — journalist and government official

- Orzubek Nazarov – former World Boxing Association lightweight boxing champion

- Nasirdin Isanov – politician, first Prime Minister of Kyrgyzstan

- Roza Otunbayeva – politician, third President of Kyrgyzstan

- Kurmanbek Bakiyev – politician, second President of Kyrgyzstan

- Sopubek Begaliev – economist, politician

See also

References

- 2009 Census preliminary results Archived 2011-07-24 at Archive.today (in Russian)

- "Ethnic composition of the population in Kyrgyzstan 1999–2014" (PDF) (in Russian). National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- 5.01.00.03 Национальный состав населения. [5.01.00.03 Total population by nationality] (XLS). Bureau of Statistics of Kyrgyzstan (in Russian, Kyrgyz, and English). 2019.

- 新疆维吾尔自治区统计局 (in Chinese). Xinjiang Bureau of Statistics.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-08-07. Retrieved 2009-12-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://92.46.60.130/open.php?exten=pdf&nn=760179%5B%5D

- "Wak.p65" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- Ukrainian population census 2001 : Distribution of population by nationality. Retrieved on 23 April 2009

- West, Barbara A., p. 440

- Mitchell, Laurence, pp. 23–24

- Mitchell, Laurence, p. 25

- West, Barbara A., p. 441

- Mitchell, Laurence, p. 24

- "Kyrgyz Religious Hatred Trial Throws Spotlight On Ancient Creed". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- Pulleyblank 1990, p.108.

- Zuev, Yu.A., Horse Tamgas from Vassal Princedoms (Translation of Chinese composition "Tanghuyao" of 8–10th centuries), Kazakh SSR Academy of Sciences, Alma-Ata, 1960, p. 103 (in Russian)

- Zuev Yu.A., Horse Tamgas from Vassal Princedoms (translation of 8-10th century Chinese Tanghuiyao), Kazakh SSR Academy of Sciences, Alma-Ata, 1960, p. 103 (in Russian)

- Rachel Lung (2011). Interpreters in Early Imperial China. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 108. ISBN 978-9027224446. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

During the reign period of Kaiyuan of [emperor] Xuanzong, Ge Jiayun composed A Record of the Western Regions, in which he said "the people of the Jiankun state all have red hair and green eyes. The ones with dark eyes were descendants of [the Chinese general] Li Ling [who was captured by the Xiongnu]...of Tiele tribe and called themselves Hegu.

- The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica: "Kirghiz" (scanned version)

- Michell, John; Valikhanov, Chokan Chingisovich; Venyukov, Mikhail Ivanovich (1865). The Russians in Central Asia: their occupation of the Kirghiz steppe and the line of the Syr-Daria : their political relations with Khiva, Bokhara, and Kokan : also descriptions of Chinese Turkestan and Dzungaria. Translated by John Michell, Robert Michell. E. Stanford. pp. 271–273.

- Vasily Bartold, Тянь-Шаньские киргизы в XVIII и XIX веках Archived 2016-01-02 at the Wayback Machine (The Tian Shan Kirghiz in the 18th and 19th centuries), Chapter VII in: Киргизы. Исторический очерк. (The Kyrgyz: an historical outline), in Collected Works of V, Bartold, Moscow, 1963, vol II, part 1, pp. 65–80 (in Russian)

- Abramzon S.M. The Kirgiz and their ethnogenetical historical and cultural connections, Moscow, 1971, p. 45

- "U.S. State Dept". U.S. State Dept. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- Abramzon S.M., p. 31

- Abramzon S.M., pp. 80–81

- Abramzon S.M., p. 30

- The Kyrgyz – Children of Manas. Кыргыздар – Манастын балдары. Petr Kokaisl, Pavla Kokaislova (2009). p.132. ISBN 80-254-6365-6

- Wells, R. S.; Yuldasheva, N.; Ruzibakiev, R.; Underhill, P. A.; Evseeva, I.; Blue-Smith, J.; Jin, L.; Su, B.; Pitchappan, R.; Shanmugalakshmi, S.; Balakrishnan, K.; Read, M.; Pearson, N. M.; Zerjal, T.; Webster, M. T.; Zholoshvili, I.; Jamarjashvili, E.; Gambarov, S.; Nikbin, B.; Dostiev, A.; Aknazarov, O.; Zalloua, P.; Tsoy, I.; Kitaev, M.; Mirrakhimov, M.; Chariev, A.; Bodmer, W. F. (2001). "The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (18): 10244–9. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810244W. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098. PMC 56946. PMID 11526236.

- Day, J. (2001). Indo-european origins: The anthropological evidence. Inst for the Study of Man. ISBN 978-0941694759.

- Figure 7c in Zerjal, Tatiana; Wells, R. Spencer; Yuldasheva, Nadira; Ruzibakiev, Ruslan; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2002). "A Genetic Landscape Reshaped by Recent Events: Y-Chromosomal Insights into Central Asia". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (3): 466–82. doi:10.1086/342096. PMC 419996. PMID 12145751.

- Zerjal, Tatiana; Wells, R. Spencer; Yuldasheva, Nadira; Ruzibakiev, Ruslan; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2002). "A Genetic Landscape Reshaped by Recent Events: Y-Chromosomal Insights into Central Asia". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (3): 466–82. doi:10.1086/342096. PMC 419996. PMID 12145751.

- Karafet 2001

- Underhill 2000

- Deka, Papiha, Chakraborty, R. S. R. (2012). Genomic diversity: Applications in human population genetics . (1st ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-1461369141

- "Wayback Machine". 24 May 2013. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013.

- Di Cristofaro J, Pennarun E, Mazières S, Myres NM, Lin AA, et al. (2013), "Afghan Hindu Kush: Where Eurasian Sub-Continent Gene Flows Converge." PLoS ONE 8(10): e76748. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076748

- Table 2 in Yao, Yong-Gang; Kong, Qing-Peng; Wang, Cheng-Ye; Zhu, Chun-Ling; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2004). "Different Matrilineal Contributions to Genetic Structure of Ethnic Groups in the Silk Road Region in China". Mol Biol Evol. 21 (12): 2265–2280. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh238. PMID 15317881.

- Martínez-Cruz, B; Vitalis, R; Ségurel, L; Austerlitz, F; Georges, M; Théry, S; Quintana-Murci, L; Hegay, T; Aldashev, A; Nasyrova, F; Heyer, E (2011). "In the heartland of Eurasia: the multilocus genetic landscape of Central Asian populations". Eur J Hum Genet. 19 (2): 216–23. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.153. PMC 3025785. PMID 20823912.

- "Kyrgyz Republic". International Religious Freedom Report 2010. U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 2010-11-23.

- Scott Cameron Levi, Ron Sela (2010). "Chapter 4, Discourse on the Qïrghïz Country". Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- Akiner, Shirin (1986). Islamic Peoples of the Soviet Union. London: Routledge. pp. 328, 337. ISBN 0-7103-0188-X.

- "Eurasianet Civil Society – Kyrgyzstan: Time to Ponder a Federal System". www.eurasianet.org. Archived from the original on 2010-11-06. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- "Kyrgyzstan: An interview with Bermet Akayeva, daughter of ex-president Askar Akayev | Women Reclaiming and Redefining Cultures". www.wluml.org. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- Estrin, James (February 4, 2013). "A Hard Life on the 'Roof of the World'". The New York Times.

- FACTBOX-Key facts about the Wakhan Corridor. Reuters. 12 June 2009

- "Mock and O'Neil, Expedition Report (2004)". Mockandoneil.com. Retrieved 2012-09-27.

- EurasiaNet (20 May 2012). "Turkey: Kyrgyz Nomads Struggle To Make Peace With Settled Existence". Eurasiareview.com. Retrieved 2012-09-27.

- "37 USES FOR A DEAD SHEEP TRAILER". Tigerlilyfilms ltd. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- "Hermann Kreutzmann (2003) Ethnic minorities and marginality in the Pamirian Knot" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2012-09-27.

- Paul Clammer (2007). Afghanistan. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-1-74059-642-8.

- Bolick, Hsi Chu. "LibGuides: Chinese Ethnic Groups: Overview Statistics". guides.lib.unc.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- Alexander Douglas Mitchell Carruthers, Jack Humphrey Miller (1914). Unknown Mongolia: a record of travel and exploration in north-west Mongolia and Dzungaria, Volume 2. Lippincott. p. 345. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- Alex Marshall (22 November 2006). The Russian General Staff and Asia, 1860–1917. Routledge. pp. 85–. ISBN 978-1-134-25379-1.

- Forbes, Andrew D. W. (1986-10-09). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521255141.

- The Kyrgyz – Children of Manas. Кыргыздар – Манастын балдары. Petr Kokaisl, Pavla Kokaislova (2009). pp.173–191. ISBN 80-254-6365-6

- Coene, Frederik (2009-10-16). The Caucasus - An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 9781135203023.

- 柯尔克孜族. China.com.cn (in Chinese). Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- The Kyrgyz – Children of Manas. Кыргыздар – Манастын балдары. Petr Kokaisl, Pavla Kokaislova (2009). p.4. ISBN 80-254-6365-6

- The Kyrgyz – Children of Manas. Кыргыздар – Манастын балдары. Petr Kokaisl, Pavla Kokaislova (2009). pp.185–188. ISBN 80-254-6365-6

- The Kyrgyz – Children of Manas. Кыргыздар – Манастын балдары. Petr Kokaisl, Pavla Kokaislova (2009). pp.259–260. ISBN 80-254-6365-6

Further reading

- Abramzon, S.M. The Kirgiz and their ethnogenetical historical and cultural connections, Moscow, 1971, ISBN 5-655-00518-2. (in Russian)

- Kyzlasov, L.R. "Mutual relationship of terms Khakas and Kyrgyz in written sources of 6–12th centuries". Peoples of Asia and Africa, 1968. (in Russian)

- Zuev, Yu.A. "Kirgiz – Buruts". Soviet Ethnography, 1970, No 4, (in Russian).

- Shahrani, M. Nazif. (1979) The Kirghiz and Wakhi of Afghanistan: Adaptation to Closed Frontiers and War. University of Washington Press. 1st paperback edition with new preface and epilogue (2002). ISBN 0-295-98262-4.

- Kyrgyz Republic, by Rowan Stewart and Susie Steldon, by Odyssey publications.

- Books by Chokan Valikhanov

- Aado Lintrop, "Hereditary Transmission in Siberian Shamanism and the Concept of the Reality of Legends"

- 2002 Smithsonian folklife festival

- Kyrgyz Healing Practices: Some Field Notes

- Politics of Language in the Ex-Soviet Muslim States: Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan by Jacob M. Landau and Barbara Kellner-Heinkele. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-472-11226-5

- Culture of Kyrgyz Republic.Well made JAPANESE pages.

- Kyrgyz Textile Art

- Pulleyblank, E.G. (1990). "The Name of the Kirghiz". Central Asiatic Journal. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. 34 (1–2): 98–108.

- Mitchell, Laurence. (2008) Kyrgyzstan: The Bradt Travel Guide. The Globe Pequot Press. 2nd edition (2012). ISBN 1-84162-221-4.

- West, Barbara A. Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania, New York, 2009, ISBN 0-8160-7109-8.

- Yu Taishan. A Note On The Geographical Location Of Jiankun // International Journal of Eurasian Studies, Beijing, 2019, No. 9. – pp. 1––5. In Chinese.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Kirghiz. |

- Kirghiz tribal tree, Center for Culture and Conflict Studies, US Naval Postgraduate School