Irish nationalism

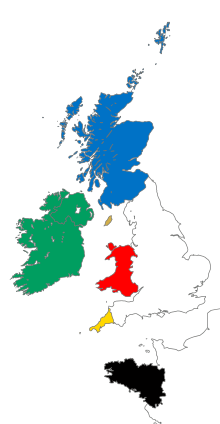

Irish nationalism is a political tradition that holds that the island of Ireland is the national territory of the Irish people, and should be comprised within a single Irish state. It emerged from the early nineteenth century as the democratic expression of Ireland's historically dispossessed Roman Catholic majority, first in the movement to repeal the 1800 Act of Union that had incorporated Ireland in a United Kingdom with Great Britain; then in the readiness of the Irish Parliamentary Party to compromise on autonomy ("Home Rule"); and finally, in the wake of World War One and of the 1916 Easter Rising, in the Republican movement for complete separation and independence. Since the creation in 1922 of an Irish state in 26 of the island's 32 counties, the focus for Irish nationalists has been on the inclusion in an all-Ireland republic of the six north-eastern counties that, with an overall Protestant majority, remained in the United Kingdom.

The nationalist appeal to history

Proclamation of the Republic

"Nationalism" is a term that gains currency from the late 1840s.[1] Whether by a secession, or a consolidation, of territories, it was understood as a claim to sovereignty on behalf of a people unrepresented in the existing concert of states. For Ireland its most enduring and consequential statement, is the Proclamation of the Irish Republic read by Patrick Pearse outside the Dublin General Post Office on April 24, 1916. This presents the Republic as a vindication of history, of an "old tradition of nationhood" sustained through generations of resistance to "usurpation... by a foreign people and government." At the same time it proposes the Republic as a realisation of principles clearly contemporary and democratic:[2] the "ownership of Ireland" by its people without distinction as to rank or creed and, in consideration of "guarantees" of "equal rights and equal opportunities", a claim to "the allegiance of every Irishman and Irishwoman".

A popular anecdote has it that when on January 16, 1922 he was tackled by the last Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Viceroy Fitzalan, for being late for the official handover of Dublin Castle, Michael Collins quipped "We've been waiting over 700 years, you can have the extra seven minutes".[3] Over the course of those 700 years those who believed themselves native to the soil contested possession with the "foreigner", but these were perceptions shaped and overridden by other interests and alignments. From Diarmait Mac Murchada's invitation to Richard de Clare, Earl of Pembroke, to cross to Wexford in 1170, servants of the English crown in Ireland rarely stood alone without native septs as allies, or faced a challenge that was not joined by those once considered part of a planted English garrison.

Confederates and Jacobites

The 1916 Proclamation places the Easter Rising in line with the "six times during the past three hundred years" the Irish people have "asserted [in arms] their right to national freedom and sovereignty." This dates the struggle for statehood until after the defeat of the last of the Gaelic lords in the Nine Years War, and to the Irish Confederate Wars that begin in 1641 with the forcible repossession of lands lost in Ulster to the Plantation of English and Scottish Protestants.

The rebels in Ulster aligned themselves with "the Roman party both English and Irish in the kingdom of Ireland",[4] the Catholic Confederacy. While claiming warrant and authority from the king, Charles I then beleaguered by his parliament in England, the coalition of Old English gentry and senior clergy comported themselves as a separate state, complete with their own national assembly in Kilkenny. Pro Deo, Rege et Patria—For God, King and Fatherland—was their motto, but this trinity pulled Confederates in different directions. In advance of the Cromwellian reconquest, the greatest of the Ulster chiefs, Owen Roe O'Neill (a veteran of service to the Spanish crown), moved against their Supreme Council condemned (and excommunicated by the Papal Nuncio) for a failure to press, not Irish claims for restitution, but the demands of the Church for a full restoration of its prerogatives "as before the Reformation".[5]

In 1916 Pearse called his Irish Volunteers “Ireland’s first standing army since the days of Patrick Sarsfield.”[6] He was invoking the memory of the defender of Limerick in 1691, not of the Jacobite cause Sarsfield loyally served. In what the Young Irelander Thomas Davis called the "Patriot Parliament" of 1689,[7] Catholic James II consented to the programme of the old Confederacy: a lifting of religious disabilities; a measured restitution of Catholic estates; and, to protect these gains, an assertion of Ireland's independence from not the English Crown but the English parliament. The issue, however, was moot. The decisive engagement was fought in 1690 on the Boyne, a battle in which, withdrawn to cover James's early retreat, Sarsfield and his command played no part.

Patriots and Volunteers

Nineteenth century Irish historians picture a second "Patriot Parliament". In April 1782 Henry Grattan passes through the "parted ranks" of drilled and armed Volunteers on College Green "to move the emancipation of his country". The House of Commons carries his declaration of legislative independence by acclaim. Barely emerging from the disastrous war in America that had given the Irish Volunteers the occasion and opportunity to organise, the London government capitulates. Having found "Ireland on her knees", Grattan pronounces her "now a nation".[8][9]

Noting that the parliament represented an exclusive Protestant Ascendancy and that the English Viceroy continued to conduct the government of Ireland much as before,[10] contemporary historians stand closer to the nineteenth-century English sources. According to Macaulay the "aboriginal inhabitants" of Ireland, "five sixths of the population", had no more interest in the contest between the College Green and Westminster parliaments "than the swine or the poultry". The patriotism of the Anglo-Irish "squireen" was as disinterested as the invocation of "inalienable right" by the "Virginia planter."[11] Froude argued that had he been "a true friend of Ireland", instead of "clamouring for an absurd independence" Grattan would have addressed the "real sores of the country." These were to be found in the tyranny of the "alien", often "absentee", landlord[12] for which, Froude suggested, even that of the Virginia planter might be too slight an analogy.

Had he been allowed to trample on [his tenants], and make them his slaves, he would have cared for them, perhaps as he cared for his horses. But their person were free, while their farms and houses were his; and thus his only object was to wring out of them the last penny which they could pay, leaving them and their children to a life scarcely raised about the level of their own pigs.[13]

The existential threat posed by this unchecked landlordism had been revealed in "Year of the Slaughter" (Irish: Bliain an Áir), the Irish Famine of 1740-41 which claimed as much as a fifth of the population.[14][15] It was confirmed again, a century later, in the Great Famine of 1845–1852, a catastrophe which, nationalists were to observe, neither Grattan's Parliament nor, from 1800, the Union parliament at Westminster, did anything to forestall.

While he allowed the common circumstance—as in the American War, Britain in 1916 was engaged elsewhere--[16] Pearse did not otherwise invite comparison between his Volunteers and those of 1782. It is not a year to which his Proclamation alludes. Yet within the Protestant ranks of the Volunteers paraded before Grattan's Parliament, there were those from whom Pearse and his comrades claimed revolutionary descent. In 1782 the largest contingents were from Ulster, and the majority of these "Dissenters" from the established Church of Ireland communion. Against the Ascendancy's sacramental tests, tithes, rack- rents, and deference to English commercial interests, Ulster Presbyterians had been turning their back, emigrating in ever growing numbers to the North American colonies (where, as the Scotch Irish of American history, they again appeared in arms).

On July 14, 1791, addressing the "great and gallant people" of France on the second anniversary of the Fall of the Bastille, "the Volunteers and Inhabitants at large of the Town and Neighbourhood of Belfast" declared: "As Irishmen, we too have a country, and we hold it very dear--so dear to us its Interest, that we wish all Civil and Religious Intolerance annihilated in this land." Those who moved this motion, and sustained it against amendments wishing only "the gradual emancipation of our Roman Catholic brethren",[17] conspired in the third of Proclamation's six occasions in which the "Irish people" asserted their right to "national freedom", the Rebellion of 1798.

The United Irishmen

In 1791 William Drennan, a Belfast obstetrician, proposed to his friends:

A benevolent conspiracy—A Plot for the People—The Brotherhood its name—the rights of Man and the greatest happiness of the greatest numbers its End. Its general end Real Independence of Ireland, and republicanism its particular purpose. Its business, every means to accomplish these ends as the prejudices and bigotry of the Land we live in would permit. . . [18]

To their first meeting, Drennan invited Theobald Wolfe Tone, author of An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland.[19] Tone maintained that in 1782 it had been "illiberal and blind" bigotry that had "lost the question": whether Ireland was to remain in her "oppressed and inglorious state", her government "derived from another country", or, through "a reform in the representation of the people", assert her sovereignty. So long as those who wished for reform "deny that civil liberty can exist out of the pale of Protestantism", present and future and administrations would be able to "indulge with ease and safety their propensity to speculation and spoil".[20]

Calling themselves, at Tone's suggestion, the Society of United Irishmen, the meeting passed three resolutions:

First--that the weight of English influence in the government of this country is so great as to require a cordial union among all the people of Ireland

Second--that the sole constitutional mode by which this influence can be opposed, is by complete and radical reform of the representation of the people in parliament.

Third--that no reform is practicable, efficacious, or just, which shall not include Irishmen of every religious persuasion.[21]

From February 1793, war with the French Republic led to the martial-law suppression of the Society, but also, in anticipation of French assistance, its spread from Belfast across the north, often under the cover of Freemasonry, and, relying upon the Defenders and other oath-bound unions of Catholic-tenantry, from Dublin across the midlands and south. In June 1795, Tone and members of the of the original Society, met atop Cave Hill overlooking Belfast and swore the celebrated oath "never to desist in our efforts until we had subverted the authority of England over our country, and asserted our independence’".[22]

With much of the leadership betrayed or with Tone in French exile, the insurrection when it came, in May and June 1798, was in a series of uncoordinated local uprisings. At least 20,000 men, women and children met with violent deaths, most from poor farming and labouring families. The confusion of tests and oaths they had taken,[23] suggest that few had "any real understanding of what the United Irishmen meant by an Irish Republic". They had drawn pikes hidden their cottage thatch for a "wide range of motives: hunger for land; revenge; sectarian hatred; and a desire to be rid of high rents, taxes and tithes".[24] Contending with an outlook more Jacobite than Jacobin, Thomas Addis Emmet, of the Society's Dublin directory, records that it was a task to persuade Defenders that "the something which [they] vaguely conceived ought to be done for Ireland was by separating it from England to establish its real as well as nominal independence".[25]

In the century to come, the pursuit of an independent republic would be identified with the most uncompromising nationalism. Yet, in their original heartland in the north, the continuity between the United Irishmen and later separatist movements was contested. Jemmy Hope, one of the very few surviving United Irishmen to remain active in the national cause, failed to raise support for Robert Emmet's aborted rising in 1803 (the fourth precedent claimed for 1916), or subsequently for Repeal—the reversal of the 1800 Acts of Union. The people among whom, Hope believed, "the republican spirit, inherent in the principles of Presbyterian community, kept resistance to arbitrary power still alive".[26] would not again support the call for an Irish constitution.

When in support of his 1886 Home Rule Bill, William Ewart Gladstone appeared to invoke the spirit of the United Irishmen (a time "when Protestants and Roman Catholics were united in the prosecution of measures for the welfare of Ireland"), the Ulster Liberal James. J. Shaw responded that had "our forefathers, [who] took up arms against an Irish Parliament" and an English crown that represented "the dominance of a cruel, selfish, and hated faction", been offered "a Union such as we enjoy with Great Britain" there would have been "no rebellion": "Catholic Emancipation, a Reformed Parliament, a responsible Executive and equal laws for the whole Irish people--these were the declared and the real objects of the United Irishmen".[27]

O'Connell and the birth of the national movement

Defining the nation

William Drennan had thought it possible that if the Union proceeded to "a full, free and frequent representation of the people in the parliament", the "distinctiveness of the Catholics" might "merge and melt away".[28] For Drennan's political nemesis, Lord Castlereagh, Chief Secretary for Ireland, such dilution was "the very logic of the Union."[29]

As it was, it took the Union thirty years to admit Catholics to Parliament by retiring the Oath of Supremacy, and then only on the basis of raising the property threshold for voters (from a forty-shilling to ten-pound freehold) so as to further discount their numbers. Elsewhere Protestants maintained their monopoly. (As landlords they were to maintain their effective grip on county government for another three generations). Whatever opportunity there might have been to integrate Irish Catholics through their re-emerging commercial and professional classes as a "dilute minority" within the United Kingdom had passed.[30] From the moment he was permitted to take his seat in Westminster, Daniel O’Connell, leader of the Catholic Association, was active in the campaign to "repeal" the Union and to restore the Kingdom of Ireland under the Constitution of 1782.

Contending under that constitution with a parliament, narrow and corrupt, but whose historic jurisdiction they had implicitly accepted, the United Irishmen had made no appeal beyond general democratic principle. As Tone discovered in Belfast, Thomas Paine's Rights of Man was their "Koran".[31] It encompassed their entire purpose including, as a condition for an accountable executive, breaking the connection with England. They did not, as republicans of 1916, look to "dead generations" for a "tradition of nationhood". For their untested union of "Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter" precedent was sought elsewhere: in America, in France and in Poland. Together with the French Constitution of that year, with its promise of amity between Catholic, Protestant and Jew the Polish Constitution of 1791 had also been celebrated in Belfast,[32] the Polish flag paraded down High Street.[33]

Repeal, however, was not reform. Once the old Kingdom had been dissolved within the wider Union, those intent upon a national government for Ireland had to preface democratic principle with the vindication of an historical right: that of the Irish as a distinct people deserving of separate representation. That there was a distinct people in Ireland—an "Irishry" without the English pale of the constitution—had never been questioned in law. From the 1537 Act of Supremacy, which declared the English king Head of the Church in Ireland, the test for that distinction (applied systematically from 1690) was not one of language (although the Ascendancy's ignorance of Irish was near complete), or of lineage (some of the Ascendancy's greatest houses could claim Gaelic descent). It was of religion. The sacrament taken or refused determined a person's protections under the law.

O'Connell was clear that "the people" who would be vindicated as the majority in a restored Irish Parliament would be those who had been so distinguished, penalised and excluded: the Roman Catholics of Ireland. His personal principles (like those of the United Irishmen of his generation) "owed a great deal to the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century". At Westminster he played a major part in passage of the Reform Act of 1832 and in the abolition of Slavery, and had proposed "a complete severance of the Church from the State".[34] Such liberalism made all the more intolerable a Union that continued to be justified as a dilution of the very people he represented. O'Connell would not abide the charge that, had they a majority whip-hand in Dublin, his constituents could not, as "Papists", be trusted with the defence of constitutional liberties.

In the face of the Union's implicit dispersion upon his church and people, O'Connell was defiant. "The Catholic Church", he declared, "is a national Church, and if the people rally to me they will have a nation for that Church".[35]

A nation for the Church

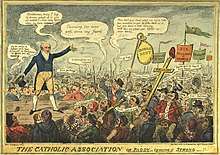

For a "Catholic rent" of a penny a month, O'Connell's Association drew the labouring poor into a mass movement. Their investment, linked by O'Connell to grievances over rents, taxes, and tithes, enabled him to mount "monster" rallies that stayed the hands of authorities, and emboldened larger tenants with the vote to cast ballots for pro-Emancipation candidates in defiance of their landlords.

O'Connell applied the same formula to campaign for Repeal. His Repealers canvassed Protestant support, maintaining for some years a reform alliance with the Whigs. But the organisation throughout much of the country remained the same, crucially dependent on the marshalling powers of the only person with standing independent of the landlord and magistrate, the local priest.

In his travels in Ireland in 1835, Alexis de Tocqueville remarked on the "unbelievable unity between the Irish clergy and the Catholic population." The people looked to the clergy, and the clergy "rebuffed" by the "upper classes" ("Protestants and enemies"), had "turned all its attention to the lower classes; it has the same instincts, the same interests and the same passions as the people; [a] state of affairs altogether peculiar to Ireland". Even among senior clergy "feelings" were to be encountered that were "extremely democratic".[36] It was an outlook reflected, to a degree, within the Church itself. When a bishop was to be appointed, De Tocqueville found that is was the assembled priests of the diocese who selected the candidates for Papal confirmation.[37]

O'Connell had still to insist that the Catholic church in Ireland was a "national church", and to protest that, while "sincerely Catholic", he did not "receive" his politics "from Rome".[38] "Friends of Emancipation", Grattan among them, proposed that continued taunts of "Popery" might be deflected if the Crown were accorded the same right exercised by continental monarchs: a veto on the confirmation of Catholic bishops. But even when, in 1814, the Curia itself proposed that bishops be "personally acceptable to the king", O'Connell was unyielding. The people would not follow a "Castle clergy".[39]

The Catholic Association rallied to O'Connell's defence of the Church's independence. Within Repeal Association its outworking was a source of division. From the 1820s the Irish hierarchy underwent a gradual generational change that reflected the Curia's increasing assertion of Papal authority. It culminates in 1850 with the appointment from Rome of Paul Cullen, Rector of the College for the Propagation of the Faith, as Primate Archbishop of Armagh. For Cullen, the first "necessity of the Church" in Ireland was "obedience to the audible word of command", and its first challenge was a relationship to a state distrusted in the first instance, not as Protestant or foreign, but as "secular and modern".[40]

For some of his younger lieutenants, still hoping for a unity of "Catholic, Protestant, and Dissenter", what was alarming in this development was that O'Connell himself appeared to anticipate its conservative and, they believed, sectarian drift.

Young Irelander dissent

In 1845 Dublin Castle proposed to educate Catholics and Protestants together in a non-denominational system of higher education. In advance of the bishops, who were more hesitant, O'Connell condemned the Queens Colleges as "an abominable attempt to undermine morality in Ireland." The principle seemingly at stake may already have been lost. When in 1830 the government had proposals to educate Catholics and Protestants together at the primary level, it had been Presbyterians who had scented danger. They refused to cooperate in National Schools unless they had the majority to ensure there would be no "mutilating of scripture."[41][42] But the vehemence of O'Connell's opposition to the colleges, was a cause of dismay among those he derided as "Young Irelanders" (a reference to Mazzini's anti-clerical and insurrectionist Young Italy).

When Tomas Davis, a Protestant, objected that "reasons for separate education are reasons for [a] separate life".[43] O'Connell, content to take a stand "for Old Ireland", accused of him of suggesting it a "crime to be a Catholic".[44]

Grouped around the paper, The Nation, which had proposed as its "first great object" a "nationality" that would embrace as easily "the stranger who is within our gates" as "the Irishman of a hundred generations,"[45] the dissidents suspected that in opposing the Colleges Bill O'Connell was also playing Westminster politics. O'Connell was keen to see a defeat for the Conservative Peel ministry and a return to office of the Whigs.

Thomas Francis Meagher denounced O'Connell's parleying with the English Liberals. The national cause was being sacrificed to a Whig government and the Irish people were being "purchased back into factious vassalage."[46] In return for damping down Repeal agitation, a "corrupt gang of politicians who fawned on O'Connell" were being allowed an extensive system of political patronage.[47]

When the split came, it was precipitated by O'Connell and on an issue, that had not been defining for the Young Irelanders, but which, increasingly, was to divide Irish Nationalism: physical force. In 1847 the Repeal Association tabled resolutions declaring that under no circumstances was a nation justified in asserting its liberties by force of arms. The Young Irelanders had never advocated physical force [48], but in response to the "Peace Resolutions” Meagher argued that if Repeal could not be carried by moral persuasion and peaceful means, a resort to arms would be a no less honourable course.[49] O'Connell's son John forced the decision: the resolution was carried on the threat of the O'Connells themselves quitting the Association.

Meagher and other prominent dissidents, among them Gavan Duffy; Jane Wilde; Margaret Callan; Thomas Meagher; William Smith O'Brien; John Blake Dillon, and Thomas Davis, withdrew and formed themselves as the Irish Confederation.

Physical Force, Tenants Rights and Ulster

1848

In the desperate circumstances of the Great Famine and in the face of new martial-law measures that had been approved by some of the Repeal Association MPs at Westminister, Young Irelanders took what Meagher considered the "honourable" course. The Battle of Ballingarry in 1848 provides the fifth precedent claimed by Pearse for the 1916 Uprising.

The resort to arms was an act of solidarity with Ribbonmen, Molly Maguires and others who, in the Famine, continued the agrarian resistance[50] Tenants had been banding together to oppose evictions, and to attack tithe and process servers, in a pattern that had been intensifying from the 1820s as land was cleared by landlords to meet the growing livestock demand from England[51] De Tocqueville recorded as a statement of their purpose:

The law does nothing for us. We must save ourselves. We have a little land which we need for ourselves and our families to live on, and they drive us out of it. To whom should we address ourselves?... Emancipation has done nothing for us. Mr. O'Connell and the rich Catholics go to Parliament. We die of starvation just the same.[52]

Fenianism

Some of the "Men of 1848" carried the commitment to physical force forward into the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), formed in 1858 in Dublin, and in the sister Fenian Brotherhood (later Clan na Gael) established by Meagher and fellow exiles in the United States. Their common, and essential proposition, was that Ireland had a natural right to independence and that this could only be won by an armed revolution.

In 1867, in a loosely co-ordinated action, the Fenians, mobilising Irish veterans of the American Civil War, raided across the northern border of the United States with a view to holding Canada hostage to the grant of Irish Independence.[53] while the IRB attempted an armed rising at home. It was the sixth and final precedent claimed by Pearse for 1916. On the even of the planned rising a proclamation was received by The Times of London:

THE IRISH PEOPLE TO THE WORLD: ...History bears testimony to our sufferings... Our war is against the aristocratic locusts, whether English or Irish, who have eaten the verdure of our fields--against aristocratic leeches who drain alike our blood and theirs. Republicans of the entire world, our cause is you cause... Avenge yourselves... Herewith we proclaim the Irish Republic.[54]

In Canada the Fenian raids were repulsed, and in Ireland, British infiltration ensured that the planned rising never got off the ground. There followed, in new dimension of an armed struggle against the British government, a series of attacks in England. Aimed at freeing "Fenian" prisoners, these included a bomb in London and the ambush of prison van in Manchester, for which three Fenians, subsequently known as the Manchester Martyrs, were executed.

With critical and continuing support from the Irish post-Famine diaspora in the United States, the IRB survived to play a critical role in organising the uprising of 1916.

Land League

Mass nationalist mobilisation began when Isaac Butt's Home Rule League (which had been founded in 1873 but had little following) adopted social issues in the late 1870s – especially the question of land redistribution.[55] Michael Davitt (an IRB member) founded the Irish Land League in 1879 during an agricultural depression to agitate for tenant's rights. Some would argue the land question had a nationalist resonance in Ireland as many Irish Catholics believed that land had been unjustly taken from their ancestors by Protestant English colonists in the 17th-century Plantations of Ireland.[56] Indeed, the Irish landed class was still largely an Anglo-Irish Protestant group in the 19th century. Such perceptions were underlined in the Land league's language and literature.[57] However, others would argue that the Land League had its direct roots in tenant associations formed in the period of agricultural prosperity during the government of Lord Palmerston in the 1850s and 1860s, who were seeking to strengthen the economic gains they had already made.[58] Following the depression of 1879 and the subsequent fall in prices (and hence profits), these farmers were threatened with rising rents and eviction for failure to pay rents. In addition, small farmers, especially in the west faced the prospect of another famine in the harsh winter of 1879. At first, the Land League campaigned for the "Three Fs" – fair rent, free sale and fixity of tenure. Then, as prices for agricultural products fell further and the weather worsened in the mid-1880s, tenants organised themselves by withholding rent during the 1886–1891 Plan of Campaign movement.

Militant nationalists such as the Fenians saw that they could use the groundswell of support for land reform to recruit nationalist support, this is the reason why the New Departure – a decision by the IRB to adopt social issues – occurred in 1879.[59] Republicans from Clan na Gael (who were loath to recognise the British parliament) saw this as an opportunity to recruit the masses to agitate for Irish self-government. This agitation, which became known as the "Land War", became very violent when Land Leaguers resisted evictions of tenant farmers by force and the British Army and Royal Irish Constabulary was used against them. This upheaval eventually resulted in the British government subsidising the sale of landlords' estates to their tenants in the Irish Land Acts authored by William O'Brien. It also provided a mass base for constitutional Irish nationalists who had founded the Home Rule League in 1873. Charles Stewart Parnell (somewhat paradoxically, a Protestant landowner) took over the Land League and used its popularity to launch the Irish National League in 1882 as a support basis for the newly formed Irish Parliamentary Party, to campaign for Home Rule.

Cultural nationalism

An important feature of Irish nationalism from the late 19th century onwards was a commitment to Gaelic Irish culture. A broad intellectual movement, the Celtic Revival, grew up in the late 19th century. Though largely initiated by artists and writers of Protestant or Anglo-Irish background, the movement nonetheless captured the imaginations of idealists from native Irish and Catholic background. Periodicals such as United Ireland, Weekly News, Young Ireland, and Weekly National Press (1891–92), became influential in promoting Ireland's native cultural identity. A frequent contributor, the poet John McDonald's stated aim was "to hasten, as far as in my power lay, Ireland's deliverance".[60]

Other organisations promoting of the Irish language or the Gaelic Revival were the Gaelic League and later Conradh na Gaeilge. The Gaelic Athletic Association was also formed in this era to promote Gaelic football, hurling, and Gaelic handball; it forbade its members to play English sports such as association football, rugby union, and cricket.

Most cultural nationalists were English speakers, and their organisations had little impact in the Irish speaking areas or Gaeltachtaí, where the language has continued to decline (see article). However, these organisations attracted large memberships and were the starting point for many radical Irish nationalists of the early twentieth century, especially the leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916 such as Patrick Pearse,[61] Thomas MacDonagh,[62] and Joseph Plunkett. The main aim was to emphasise an area of difference between Ireland and Germanic England, but the majority of the population continued to speak English.

The cultural Gaelic aspect did not extend into actual politics; while nationalists were interested in the surviving Chiefs of the Name, the descendants of the former Gaelic clan leaders, the chiefs were not involved in politics, nor noticeably interested in the attempt to recreate a Gaelic state.

Home Rule beginnings

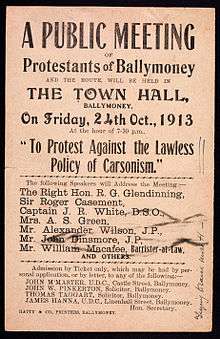

Although Parnell and some other Home Rulers, such as Isaac Butt, were Protestants, Parnell's party was overwhelmingly Catholic. At local branch level, Catholic priests were an important part of its organisation. Home Rule was opposed by Unionists (those who supported the Union with Britain), mostly Protestant and from Ulster under the slogan, "Home Rule is Rome Rule."

At the time, some politicians and members of the British public would have seen this movement as radical and militant. Detractors quoted Charles Stewart Parnell's Cincinnati speech in which he claimed to be collecting money for "bread and lead". He was allegedly sworn into the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood in May 1882. However, the fact that he chose to stay in Westminster following the expulsion of 29 Irish MPs (when those in the Clan expected an exodus of nationalist MPs from Westminster to set up a provisional government in Dublin) and his failure in 1886 to support the Plan of Campaign (an aggressive agrarian programme launched to counter agricultural distress), marked him as an essentially constitutional politician, though not averse to using agitational methods as a means of putting pressure on parliament.

Coinciding as it did with the extension of the franchise in British politics – and with it the opportunity for most Irish Catholics to vote – Parnell's party quickly became an important player in British politics. Home Rule was favoured by William Ewart Gladstone, but opposed by many in the British Liberal and Conservative parties. Home Rule would have meant a devolved Irish parliament within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The first two Irish Home Rule Bills were put before the House of Commons of the United Kingdom in 1886 and 1893, but they were bitterly resisted and the second bill ultimately defeated in the Conservative's pro-Unionist majority controlled House of Lords.

Following the fall and death of Parnell in 1891 after a divorce crisis, which enabled the Irish Roman Catholic hierarchy to pressure MPs to drop Parnell as their leader, the Irish Party split into two factions, the INL and the INF becoming practically ineffective from 1892 to 1898. Only after the passing of the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 which granted extensive power to previously non-existent county councils, allowing nationalists for the first time through local elections to democratically run local affairs previously under the control of landlord dominated "Grand Juries", and William O'Brien founding the United Irish League that year, did the Irish Parliamentary Party reunite under John Redmond in January 1900, returning to its former strength in the following September general election.

From home rule to independence

Transformation of rural Ireland

The first decade of the twentieth century saw considerable advancement in rural economic and social development in Ireland where 60% of the population lived.[63] The introduction of local self-government in 1898 created a class of experienced politicians capable of later taking over national self-government in the 1920s. O'Brien's attainment of the 1903 Wyndham Land Act (the culmination of land agitation since the 1880s) abolished landlordism, and made it easier for tenant farmers to purchase lands, financed and guaranteed by the government. By 1914, 75 per cent of occupiers were buying out their landlords' freehold interest through the Land Commission, mostly under the Land Acts of 1903 and 1909.[64] O'Brien then pursued and won in alliance with the Irish Land and Labour Association and D.D. Sheehan, who followed in the footsteps of Michael Davitt, the landmark 1906 and 1911 Labourers (Ireland) Acts, where the Liberal government financed 40,000 rural labourers to become proprietors of their own cottage homes, each on an acre of land. "It is not an exaggeration to term it a social revolution, and it was the first large-scale rural public-housing scheme in the country, with up to a quarter of a million housed under the Labourers Acts up to 1921, the majority erected by 1916",[65] changing the face of rural Ireland.

The combination of land reform and devolved local government gave Irish nationalists an economic political base on which to base their demands for self-government. Some in the British administration felt initially that paying for such a degree of land and housing reform amounted to an unofficial policy of "killing home rule by kindness", yet by 1914 some form of Home Rule for most of Ireland was guaranteed. This was shelved on the outbreak of World War I in August 1914.

A new source of radical Irish nationalism developed in the same period in the cities outside Ulster. In 1896, James Connolly, founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party in Dublin. Connolly's party was small and unsuccessful in elections, but his fusion of socialism and Irish republicanism was to have a sustained impact on republican thought. In 1913, during the general strike known as the Dublin Lockout, Connolly and James Larkin formed a workers militia, the Irish Citizen Army, to defend strikers from the police. While initially a purely defensive body, under Connolly's leadership, the ICA became a revolutionary body, dedicated to an independent Workers Republic in Ireland. After the outbreak of the First World War, Connolly became determined to launch an insurrection to this end.

Home rule crisis 1912–14

Home Rule was eventually won by John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party and granted under the Third Home Rule Act 1914. However, Irish self-government was limited by the prospect of partition of Ireland between north and south. This idea had first been mooted under the Second Home Rule Bill in 1893. In 1912, following the entry of the Third Home Rule Bill through the House of Commons, unionists organised mass resistance to its implementation, organising around the "Ulster Covenant". In 1912 they formed the Ulster Volunteers, an armed wing of Ulster Unionism who stated that they would resist Home Rule by force. British Conservatives supported this stance. In addition, British officers based at the Curragh indicated that they would be unwilling to act against the Ulster Volunteers should they be ordered to.

In response, Nationalists formed their own paramilitary group, the Irish Volunteers, to ensure the implementation of Home Rule. It looked for several months in 1914 as if civil war was imminent between the two armed factions. Only the All-for-Ireland League party advocated granting every conceivable concession to Ulster to stave off a partition amendment. Redmond rejected their proposals. The amended Home Rule Act was passed and placed with Royal Assent on the statute books, but was suspended after the outbreak of World War I in 1914, until the end of the war. This led radical republican groups to argue that Irish independence could never be won peacefully and gave the northern question little thought at all.

World War I and the Easter Rising

The Irish Volunteer movement was divided over the attitude of their leadership to Ireland's involvement in World War I. The majority followed John Redmond in support of the British and Allied war effort, seeing it as the only option to ensure the enactment of Home Rule after the war, Redmond saying "you will return as an armed army capable of confronting Ulster's opposition to Home Rule". They split off from the main movement and formed the National Volunteers, and were among the 180,000 Irishmen who served in Irish regiments of the Irish 10th and 16th Divisions of the New British Army formed for the War.

A minority of the Irish Volunteers, mostly led by members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), refused to support the War and kept their arms to guarantee the passage of Home Rule. Within this grouping, another faction planned an insurrection against British rule in Ireland, while the War was going on. Critical in this regard were Patrick Pearse,[66] Thomas MacDonagh, and Thomas Clarke. These men were part of an inner circle that were operating in secret within the ranks of the IRB to plan this rising unknown to the rest of the volunteers.[67] James Connolly, the labour leader, first intended to launch his own insurrection for an Irish Socialist Republic decided early in 1916 to combine forces with the IRB. In April 1916, just over a thousand dissident Volunteers and 250 members of the Citizen's Army launched the Easter Rising in the Dublin General Post Office and, in the Easter Proclamation, proclaimed the independence of the Irish Republic. The Rising was put down within a week, at a cost of about 500 killed, mainly unengaged civilians.[68] Although the rising failed, Britain's General Maxwell executed fifteen of the Rising's leaders, including Pearse, MacDonagh, Clarke and Connolly, and arrested some 3000 political activists which led to widespread public sympathy for the rebel's cause. Following this example, physical force republicanism became increasingly powerful and, for the following seven years or so, became the dominant force in Ireland, securing substantial independence but at a cost of dividing Ireland.[69]

The Irish Parliamentary Party was discredited after Home Rule had been suspended at the outbreak of World War I, in the belief that the war would be over by the end of 1915, then by the severe losses suffered by Irish battalions in Gallipoli at Cape Helles and on the Western Front. They were also damaged by the harsh British response to the Easter Rising, who treated the rebellion as treason in time of war when they declared martial law in Ireland. Moderate constitutional nationalism as represented by the Irish Party was in due course eclipsed by Sinn Féin — a hitherto small party which the British had (mistakenly) blamed for the Rising and subsequently taken over as a vehicle for Irish Republicanism.

Two further attempts to implement Home Rule in 1916 and 1917 also failed when John Redmond, leader of the Irish Party, refused to concede to partition while accepting there could be no coercion of Ulster. An Irish Convention to resolve the deadlock was established in July 1917 by the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, its members both nationalists and unionists tasked with finding a means of implementing Home Rule. However, Sinn Féin refused to take part in the Convention as it refused to discuss the possibility of full Irish independence. The Ulster unionists led by Edward Carson insisted on the partition of six Ulster counties from the rest of Ireland[70] stating that the 1916 rebellion proved a parliament in Dublin could not be trusted.

The Convention's work was disrupted in March 1918 by Redmond's death and the fierce German Spring Offensive on the Western Front, causing Britain to attempt to contemplate extending conscription to Ireland. This was extremely unpopular, opposed both by the Irish Parliamentary Party under its new leader John Dillon, the All-for-Ireland Party as well as Sinn Féin and other national bodies. It resulted in the Conscription Crisis of 1918. In May at the height of the crisis 73 prominent Sinn Féiners were arrested on the grounds of an alleged German Plot. Both these events contributed to a widespread rise in support for Sinn Féin and the Volunteers.[71] The Armistice ended the war in November followed by elections.

Militant separatism and Irish independence

In the General election of 1918, Sinn Féin won 73 seats, 25 of these unopposed, or statistically nearly 70% of Irish representation, under the British "First past the post" voting-system, but had a minority representation in Ulster. They achieved a total of 476,087 (46.9%) of votes polled for 48 seats, compared to 220,837 (21.7%) votes polled by the IPP for only six seats, who due to the "first past the post" voting system did not win a proportional share of seats.[72] Unionists (including Unionist Labour) votes were 305,206 (30.2%)[73]

The Sinn Féin MPs refused to take their seats in Westminster, 27 of these (the rest were either still imprisoned or impaired) setting up their own Parliament called the Dáil Éireann in January 1919 and proclaimed the Irish Republic to be in existence. Nationalists in the south of Ireland, impatient with the lack of progress on Irish self-government, tended to ignore the unresolved and volatile Ulster situation, generally arguing that unionists had no choice but to ultimately follow. On 11 September 1919, the British proscribed the Dáil, it had met nine times, declaring it an illegal assembly, Ireland being still part of the United Kingdom. In 1919, a guerilla war broke out between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) (as the Irish Volunteers were now calling themselves) and the British security[74] forces (See Irish War of Independence).

The campaign created tensions between the political and military sides of the nationalist movement. The IRA, nominally subject to the Dáil, in practice, often acted on its own initiative. At the top, the IRA leadership, of Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy, operated with little reference to Cathal Brugha, the Dáil's Minister for Defence or Éamon de Valera, the President of the Irish Republic – at best giving them a supervisory role.[75] At local level, IRA commanders such as Dan Breen, Sean Moylan, Tom Barry, Sean MacEoin, Liam Lynch and others avoided contact with the IRA command, let alone the Dáil itself.[76] This meant that the violence of the War of Independence rapidly escalated beyond what many in Sinn Féin and Dáil were happy with.[76] Arthur Griffith, for example, favoured passive resistance over the use of force, but he could do little to affect the cycle of violence between IRA guerrillas[76] and Crown forces that emerged over 1919–1920. The military conflict produced only a handful of killings in 1919, but steadily escalated from the summer of 1920 onwards with the introduction of the paramilitary police forces, the Black and Tans and Auxiliary Division into Ireland. From November 1920 to July 1921, over 1000 people lost their lives in the conflict (compared to c.400 up to then).

Present day

Northern Ireland is not a part of the Republic, but it has a nationalist minority who would prefer to be part of a united Ireland. In Northern Ireland, the term "nationalist" is used to refer either to the Catholic population in general or the supporters of the moderate Social Democratic and Labour Party. "Nationalism" in this restricted meaning refers to a political tradition that favours an independent, united Ireland achieved by non-violent means. The more militant strand of nationalism, as espoused by Sinn Féin, is generally described as "republican" and was regarded as somewhat distinct, although the modern-day party claims to be a constitutional party committed to exclusively peaceful and democratic means.

56% of Northern Irish voters voted for the United Kingdom to remain a part of the European Union in the 23 June 2016 Referendum in which the country as a whole voted to leave the union. The results in Northern Ireland were influenced by fears of a strong border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland as well as by fears of a hard border breaking the Good Friday Agreement.[77]

Organisations (1791–present)

18th Century

19th Century

- Catholic Association

- Repeal Association

- Irish Confederation

- Young Ireland

- Irish National Invincibles

- Home Government Association

- Home Rule League

- Irish Parliamentary Party

20th century

- 32 County Sovereignty Movement

- Ailtirí na hAiséirghe

- Aontacht Éireann

- Blueshirts

- Clann na Poblachta

- Continuity Irish Republican Army

- Córas na Poblachta

- Cumann na nGaedheal

- Cumann Poblachta na hÉireann

- Fianna Fáil

- Fine Gael

- Greenshirts

- Irish Independence Party

- Irish National Liberation Army

- Irish People's Liberation Organisation

- Irish Republican Army (1919–22)

- Irish Republican Army (1922–69)

- Irish Republican Socialist Party

- National Corporate Party

- Official Irish Republican Army

- Provisional Irish Republican Army

- Real Irish Republican Army

- Republican Sinn Féin

- Saor Éire

- Saor Éire (1967–75)

- Saor Uladh

- Social Democratic and Labour Party

- Sinn Féin

21st century

See also

- Gerry Adams

- Joseph Biggar

- Roger Casement

- Erskine Childers

- Molly Childers

- Thomas Clarke

- James Connolly

- Michael Corcoran

- Thomas Davis

- Kevin Izod O'Doherty

- Michael Doheny

- Charles Gavan Duffy

- Denis Ireland

- James Fintan Lalor

- Sean MacDiarmada

- Thomas MacDonagh

- Terence MacManus

- Eoin MacNeill

- Sean McBride

- John Martin

- Thomas Francis Meagher

- John Mitchel

- D. P. Moran

- Daniel O'Connell

- Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa

- John Dooley Reigh

- Patrick O'Donoghue

- Charles Stewart Parnell

- Patrick Pearse

- John Edward Pigot

- John Redmond

- Thomas Devin Reilly

- Irish Race Conventions

- Protestant Irish nationalists

- Unionism in Ireland

- Cultural imperialism

References

Citations

- Rich, Norman (1976). The Age of Nationalism and Reform, 1850 -1890 (The Norton History of Modern Europe. New York: W H Norton. ISBN 9780393091830.

- Smith, Deanna (2007). Nationalism (2nd ed.). Cambridge: polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-5128-6.

- Coogan, Tim Pat (1991). Michael Collins, a Biography. London: Arrow Books. p. 310. ISBN 978-0099685807.

- Hickson, Mary; Ireland in the Seventeenth Century Longmans, London 1884, p. 113

- Foster, R. F. (1988). Modern Ireland 1600-1972. London: Allen Lane. p. 98. ISBN 0-7139-9010-4.

- Mulvagh, Conor (29 October 2015). "Joseph Mary Plunkett, Ailing writer who shaped the rebellion" (PDF). Irish Independent. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Thomas Davis (1843), "A Patriot Parliament", The Nation, 1 April, p. 392

- Lecky, William H. E. (1913). History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century, Vol. II [1891]. London: Longmans, Green & Co. pp. 249–252.

- O'Brien, R. Barry (1896). Ireland. London: Fisher Unwin. pp. 219–221.

- Foster, R. F. (1976). Modern Ireland 1600-1972. London: Allen Lane. p. 251. ISBN 0713990104.

- Macaulay, Lord (1864). The History of England from the Accession of James II. London: Longman, Green & Co. pp. IV 231–232, III 287.

- Froude, James Anthony (1882). The English in Ireland in the Eighteenth Century. London: Longman, Green & Co. p. 498.

- Froude quoted in O'Brien, p.209

- Cathal Póirtéir, (ed.) The Great Irish Famine (1955), Mercier Press, pp. 53–55

- James Kelly, Food Rioting in Ireland in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, Four Courts Press, 2017, p. 36

- Augusteijn, Joost (2010). Patrick Pearse: The Making of a Revolutionary. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 256.

- William Bruce and Henry Joy, ed. (1794). Belfast politics: or, A collection of the debates, resolutions, and other proceedings of that town in the years 1792, and 1793. Belfast: H. Joy & Co. pp. 52–65.

- "Category Archives: William Drennan". assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. February 2020. pp. 15–16. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Theobald Wolfe Tone (1791). An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland. Belfast: H. Joy & Co.

- Theobald Wolfe Tone (1791). An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland. Belfast: H. Joy & Co.

- Altholz, Josef L. (2000). Selected Documents in Irish History. New York: M E Sharpe. p. 70. ISBN 0415127769.

- William Theobald Wolfe Tone, ed. (1826). Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, vol. 1. Washington D.C.: Gales and Seaton. p. 127.

- Curtin, Nancy (1985). "The Transformation of the Society of United Irishmen into a mass-based revolutionary organisation, 1794-6". Irish Historical Studies. xxiv (96): 464–492.

- Bardon, Jonathan (2008). A History of Ireland in 250 Episodes. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. p. 327. ISBN 9780717146499.

- Curtin, Nancy (1985). "The Transformation of the Society of United Irishmen into a mass-based revolutionary organisation, 1794-6". Irish Historical Studies. xxiv (96): 483, 486.

- Bardon, Jonathan (1982). Belfast: An Illustrated History. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. p. 60. ISBN 0856402729.

- Shaw, James J. (1888). Mr. Gladstone's Two Irish Policies: 1868-1886 (PDF). London: Marcus Ward. pp. 0–11.

- William Drennan, Belfast Monthly Magazine, 7 (1811) quoted in Jonathan Jeffrey Wright (2013), The 'Natural Leaders' and their World: Politics, Culture and Society in Belfast c.1801-1832, University of Liverpool Press (ISBN 9781846318481), p.75

- John Bew, Castlereagh. Enlightenment, War and Tyranny. Quercas. London 2012. P. 126

- Foster, R. F. (1988). Modern Ireland 1600-1972. London: Allen Lane. p. 291. ISBN 0-7139-9010-4.

- William Theobald Wolfe Tone, ed. (1826). Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, vol. I. Washington D.C.: Gales and Seaton. p. 141.

- Healy, Róisín (2017). Poland in the Irish Nationalist Imagination, 1772–1922: Anti-Colonialism within Europe. Dublin: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 47. ISBN 9783319434308.

- Madden, Richard (1843). The United Irishmen, Their Lives and Times. J. Madden & Company. p. 179.

- O'Farrell, Fegus (1986). "Daniel O'Connell and Henry Cooke: The Conflict of Civil and Religious Liberty in Modern Ireland". Irish Review. no 1: 20–27, 24–25.

- Quoted in Boyce, D. George. (1995). Nationalism in Ireland (Third Edition). London: Routledge. p. 146. ISBN 9780415127769.

- de Tocqueville, Alexis. (1968). Journeys to England and Ireland [1833-35]. New York: Anchor Books. pp. 127–128, 121.

- de Tocqueville, Alexis. (1968). Journeys to England and Ireland [1833-35]. New York: Anchor Books. p. 125.

- Luby, Thomas Clarke (1870). The life and times of Daniel O'Connell. Glasgow: Cameron, Ferguson & Company. p. 418.

- O'Brien, R. Barry (2014). Two Centuries of Irish History: 1691-1870 (1907 edition). New York: Routledge. pp. 241–243. ISBN 9781315796994.

- Keogh, Dáire; McDonnell, Albert (2011). Cardinal Paul Cullen and his world. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 9781846822353.

- Shearman, Hugh (1952). Modern Ireland. London: George G. Harrap & Co. pp. 84–85.

- Andrew R. Holmes (2007), The Shaping of Ulster Presbyterian Belief & Practice 1770-1840 Oxford

- Macken, Ultan (2008). The Story of Daniel O'Connell. Cork: Mercier Press. p. 120. ISBN 9781856355964.

- Mulvey, Helen (2003). Thomas Davis and Ireland: A Biographical Study. Washington DC: The Catholic University of America Press. p. 180. ISBN 0813213037.

- Bardon, Jonathan (2008). A History of Ireland in 250 Episodes. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. p. 367.

- O'Sullivan, T. F. (1945). Young Ireland. The Kerryman Ltd. p. 195

- Griffith, Arthur (1916). Meagher of the Sword:Speeches of Thomas Francis Meagher in Ireland 1846–1848. Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son, Ltd. p. vii

- Doheny, Michael (1951). The Felon's Track. Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son. p. 105

- O'Sullivan, T. F. (1945). Young Ireland. The Kerryman Ltd. pp. 195-6

- Fenton, Laurence (2010). The Young Ireland Rebellion and Limerick. Cork: Mercier Press. pp. 46–48. ISBN 978-1-85635-660-2. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Murray, A.C. (1986). "Agrarian Violence and Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Ireland: the Myth of Ribbonism". Irish Economic and Social History. 13: 56–73. doi:10.1177/033248938601300103. JSTOR 24337381.

- de Tocqueville, Alexis. (1968). Journeys to England and Ireland [1833-35]. New York: Anchor Books. p. 123.

- Senior, Hereward (1991). The Last Invasion of Canada: The Fenian Raids, 1866-1870. Dundurn. ISBN 9781550020854. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Bardon, Jonathan (2008). A History of Ireland in 250 Episodes. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. p. 389. ISBN 9780717146499.

- Kee 1972, p. 351–376.

- Kee 1972, p. 15–21.

- Kee 1972, p. 364–376.

- Kee 1972, p. 299–311.

- Kee 1972, p. 330–351.

- O'Donoghue 1892, pp. 144.

- Sean Farrell Moran, "Patrick Pearse and the European Revolt Against Reason," Journal of the History of Ideas, 1989; Patrick Pearse and the Politics of Redemption, (1994),

- Johann Norstedt, Thomas MacDonagh, (1980)

- Kee 1972, p. 422–426.

- Ferriter, Diarmaid, The Transformation of Ireland 1900–2000 (2005) pp. 38+62

- Ferriter, Diarmaid, The Transformation of Ireland 1900–2000, (2004) pp 159

- Sean Farrell Moran, "Patrick Pearse and the Politics of Redemption", (1995), Ruth Dudley Edwards, "Patrick Pearse and the Triumph of Failure," (1974), Joost Augustin, "Patrick Pearse," (2009).

- Robert., Kee (1989). The green flag. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0140111042. OCLC 19668723.

- Kee 1972, p. 548–591.

- Kee 1972, p. 591–719.

- ME Collins, Ireland 1868–1966, page 240

- Sovereignty and partition, 1912–1949, p. 59, M. E. Collins, Edco Publishing (2004) ISBN 1-84536-040-0

- Sovereignty and partition, 1912–1949, p.62, M. E. Collins, Edco Publishing (2004) ISBN 1-84536-040-0

- B.M. Walker Parliamentary Election Results in Ireland, 1801–1822

- Kee 1972, p. 651–698.

- Kee 1972, p. 611 et passim.

- Kee 1972, p. 651–656.

- "Now, IRA stands for I Renounce Arms". The Economist. 28 July 2005.

Sources

- Kee, Robert (1972). The Green Flag: A History of Irish Nationalism. ISBN 0-297-17987-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Donoghue, David James (1892). The Poets of Ireland: A Biographical Dictionary with Bibliographical Particulars (PDF).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Brundage, David. Irish Nationalists in America: The Politics of Exile, 1798–1998 (Oxford UP, 2016). x, 288

- Boyce, D. George. Nationalism in Ireland, 1982.

- Campbell, F. Land and Revolution,2005

- Cronin, Sean. Irish Nationalism: Its Roots and Ideology, 1980.

- Edwards, Ruth Dudley, Patrick Pearse: The Triumph of Failure, 1977.

- Elliot, Marianne, Wolfe Tone, 1989.

- English, Richard. Irish Freedom, 2008.

- Garvin, Tom. The Evolution of Irish Nationalist Politics, 1981; Nationalist Revolutionaries in Ireland, 1858-1928, 1987

- Kee, Robert. The Green Flag, 1976.

- MacDonagh, Oliver. States of Mind, 1983

- McBride, Lawrence. Images, Icons, and the Irish Nationalist Imagination, 1999.

- McBride, Lawrence. Reading Irish Histories, 2003.

- Maume, Patrick. The Long Gestation, 1999.

- Nelson, Bruce. Irish Nationalists and the Making of the Irish Race. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- Strauss, E. Irish Nationalism and British Democracy, 1951.

- O'Farrell, Patrick. Ireland's English Question, 1971.

- Phoenix, E. Northern Nationalism,

- Ward, Margaret. Unimaginable Revolutionaries: Women and Irish Nationalism, 1983

External links

- Irish Nationalism (Archived 2009-10-31) – ninemsn Encarta (short introduction)