Coptic nationalism

Coptic nationalism refers to the nationalism of Copts (Coptic: ⲚⲓⲢⲉⲙ̀ⲛⲭⲏⲙⲓ ̀ⲛ̀Ⲭⲣⲏⲥⲧⲓ̀ⲁⲛⲟⲥ Niremenkīmi Enkhristianos, Arabic: أقباط Aqbat), an ethno-religious group[1] that primarily inhabit the area of modern Egypt, where they are the largest Christian denomination.

| Part of the series on |

| Copts |

|---|

| Culture |

| Regions |

| Denominations |

| Language |

| Writing Systems |

Pharaonism

Questions of Egyptian identity rose to prominence in Egypt in the 1920s and 1930s as Egyptians sought independence from British occupation. The Pharaonist movement, or Pharaonism, looks to Egypt's pre-Islamic past and argued that Egypt was part of a larger Mediterranean civilization. Many Coptic intellectuals hold to "Pharaonism," which states that Coptic culture is largely derived from pre-Christian, Pharaonic culture, and is not indebted to Greece. It gives the Copts a claim to a deep heritage in Egyptian history and culture. Pharaonism was widely held by Coptic scholars in the early 20th century. Most scholars today see Pharaonism as a late development shaped primarily by western Orientalism, and doubt its validity.[2][3]

Coptic identity

Coptic identity as it stands now saw its roots in the 1950s with the rise of pan-Arabism under Nasser. Up to that point, Egyptian nationalism was the major form of expression for Egyptian identity,[4] Copts viewed themselves as only Copts without any Arab sentiment.[5] The struggle to ascertain this Egyptian identity began as Nasser and his regime tried to impose an Arab identity on the country, and attempted to erase all references to Egypt as a separate and unique entity.[6]

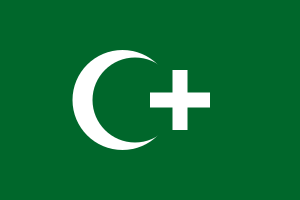

Ethnic flag (2005)

| |

| Use | Ethnic flag |

|---|---|

| Proportion | |

| Adopted | 2005 |

| Design | The Coptic shield on a blue cross on a field of white. |

| Designed by | The Free Copts |

A Coptic flag was created in 2005 by a Coptic activist group called "The Free Copts" as an ethnic flag representing Copts, Coptic identity and as a sign of opposition to Islamic authority in Egypt.[7] It is not recognized by the Coptic Orthodox Church or the Coptic Catholic Church but has been adopted by the New Zealand Coptic Association.

The Coptic Flag consists of two main components: a blue cross and a colorful coat of arms.

- The cross represents Christianity, the Copts' religion. The blue color stems from the Egyptian sky and water. It also reminds the Copts of their persecution, when some of Muslim rulers forced their ancestors to wear heavy crosses around their necks until their necks became blue.[8][9]

- The top of the coat of arms is decorated with Coptic crosses intertwined with lotus flowers, representing Egyptian identity. Coptic crosses are made of four arms equal in length, each of which is crossed by a shorter arm (similar to the heraldic cross crosslet fitchy or cross bottony). The lotus flower, also known as the Egyptian White Water-lily (Nymphaea lotus), has been a symbol of creation since Ancient Egyptian times. Remains of the flower were found in the burial tomb of Pharaoh Ramesses II. Hence, its use on the flag represents the desire of all Coptic people to overthrow the Arab Islamic government and restore a native monarchy.

The black background behind the ornaments is a symbol of Kimi or Kemet, the Egyptian name of Egypt, which means the Black Land. Beneath these ornaments is a green line in the middle of the coat of arms, which represents the Nile Valley. Around it are two yellow lines that symbolize the Eastern and Western Deserts of Egypt. These two lines are in turn flanked by two blue lines that represent the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea that enclose Egypt. Finally, these lines are separated by red lines symbolizing Coptic blood, which has been shed all over Egypt since Copts adopted Christianity and until today.

See also

References

- Minahan 2002, p. 467

- van der Vliet, Jacques (June 2009), "The Copts: 'Modern Sons of the Pharaohs'?", Church History & Religious Culture, 89 (1–3): 279–90, doi:10.1163/187124109x407934.

- Reid, Donald Malcolm (2003). "7". Whose Pharaohs?: Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian National Identity from Napoleon to World War I. U. of California Press. pp. 258ff.

- Haeri, Niloofar. Sacred language, Ordinary People: Dilemmas of Culture and Politics in Egypt. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2003, pp. 47, 136.

- Deighton, H. S. "The Arab Middle East and the Modern World", International Affairs, vol. xxii, no. 4 (October 1946), p. 519.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-04-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "The Coptic Flag, Meanings and Colors by The Free Copts". Archived from the original on 2007-01-14. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- My Coptic Church - Ask A Copt

- El-Shamy, Hasan M. Folktales of Egypt. 406 p. 1980 Series: (FW) Folktales of the World ISBN 978-0-226-20625-7 (ISBN 0-226-20625-4)

Bibliography

- Shatzmiller, Maya (2005). Nationalism and Minority Identities in Islamic Societies. McGill-Queen's Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lin Noueihed, Alex Warren. The Battle for the Arab Spring: Revolution, Counter-Revolution and the Making of a New Era. Yale University Press, 2012.