Crimean Tatar language

Crimean Tatar (qırımtatar tili, къырымтатар тили), also called Crimean (qırım tili, къырым тили),[1] is a Kipchak Turkic language spoken in Crimea and the Crimean Tatar diasporas of Uzbekistan, Turkey, Romania and Bulgaria, as well as small communities in the United States and Canada. It should not be confused with Tatar proper, spoken in Tatarstan and adjacent regions in Russia; the languages are related, but belong to two different subgroups of the Kipchak languages and thus are not mutually intelligible. It has been extensively influenced by nearby Oghuz dialects.

| Crimean Tatar | |

|---|---|

| Crimean | |

| qırımtatar tili, къырымтатар тили qırım tili, къырым тили | |

| Native to | Ukraine, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Romania, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Bulgaria, Lithuania |

| Region | Black Sea |

| Ethnicity | Crimean Tatars |

Native speakers | 540,000 (2006–2011)[1] |

| Officially Latin but Cyrillic is also widely used in the Crimea; previously Arabic (Crimean Tatar alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | crh |

| ISO 639-3 | crh |

| Glottolog | crim1257[5] |

| Linguasphere | part of 44-AAB-a |

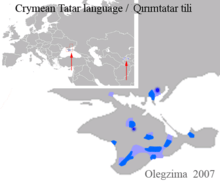

Crimean Tatar-speaking world | |

| Part of a series on |

| Crimean Tatars |

|---|

|

| By region or country |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

| History |

| People and groups |

|

Number of speakers

Today, more than 260,000 Crimean Tatars live in Crimea. Approximately 150,000 reside in Central Asia (mainly in Uzbekistan), where their ancestors had been deported in 1944 during World War II by the Soviet Union. However, of all these people, mostly the older generations are the only ones still speaking Crimean Tatar.[6] In 2013, the language was estimated to be on the brink of extinction, being taught in only around 15 schools in Crimea. Turkey has provided support to Ukraine, to aid in bringing the schools teaching in Crimean Tatar to a modern state.[7] An estimated 5 million people of Crimean origin live in Turkey, descendants of those who emigrated in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Of these an estimated 2,000 still speak the language.[6] Smaller Crimean Tatar communities are also found in Romania (22,000), Bulgaria (6,000), and the United States.[6] Crimean Tatar is one of the seriously endangered languages in Europe.[8]

Almost all Crimean Tatars are bilingual or multilingual, using as their first language the dominant languages of their respective home countries, such as Russian, Turkish, Romanian, Uzbek, Bulgarian or Ukrainian.

Classification and dialects

Crimean Tatar is conventionally divided into three main dialects: northern, middle and southern.

The middle dialect is spoken in the Crimean Mountains by the sedentary Tat Tatars (should not be confused with the Tat people which speak an Iranic language). The modern Crimean Tatar written language is based on Tat Tatar because the Tat Tatars comprise a relative majority.

Standard Crimean Tatar and its middle dialect are classified as a language of the Cuman (Russian: кыпчакско-половецкая) subgroup of the Kipchak languages and the closest relatives are Karachay-Balkar, Karaim, Krymchak, Kumyk, Urum and extinct Cuman.

However, two other unwritten dialects of Crimean Tatar belong to two different groups or subgroups of the Turkic languages.

The northern dialect (also known as steppe or Nogay) is spoken by the Noğay ethnic subgroup, the former nomadic inhabitants of the Crimean (Nogay) steppe (should not be confused with Nogai people of the Northern Caucasus and the Lower Volga). This dialect belongs to the Nogay (Russian: кыпчакско-ногайская) subgroup of the Kipchak languages. This subgroups also includes Kazakh, Karakalpak, Kyrgyz, and Nogai proper. It is thought that the Nogays of the Crimea and the Nogais of the Caucasus and Volga are of common origin from the Nogai Horde, which is reflected in their common name and very closely related languages. In the past some speakers of this dialects also called themselves Qıpçaq (that is Cumans).

The southern or coastal dialects is spoken by Yalıboylu ("coastal dwellers") who have traditionally lived on the southern coast of the Crimea. Their dialects belongs to the Oghuz group of the Turkic languages which includes Turkish, Azeri and Turkmen. This dialect is most heavily influenced by Turkish.

Thus, Crimean Tatar has a unique position among the Turkic languages, because its three "dialects" belong to three different (sub)groups of Turkic. This makes the classification of Crimean Tatar as a whole difficult. The middle dialect, although thought to be of Kipchak-Cuman origin, in fact combines elements of both Cuman and Oghuz languages. This latter fact may also be another reason why Standard Crimean Tatar has had its basis in the middle dialect.

Volga Tatar

Because of its common name, Crimean Tatar is sometimes mistaken to be a dialect of Tatar proper, or both being two dialects of the same language. However, Tatar spoken in Tatarstan and the Volga-Ural region of Russian belongs to the different Bulgaric (Russian: кыпчакско-булгарская) subgroup of the Kipchak languages, and its closet relative is Bashkir. Both Volga Tatar and Bashkir differ notably from Crimean Tatar, particularly because of the specific Volga-Ural Turkic vocalism and historical shifts.

History

The formation period of the Crimean Tatar spoken dialects began with the first Turkic invasions of Crimea by Cumans and Pechenegs and ended during the period of the Crimean Khanate. However, the official written languages of the Crimean Khanate were Chagatai and Ottoman Turkish. After Islamization, Crimean Tatars wrote with an Arabic script.

In 1876, the different Turkic Crimean dialects were made into a uniform written language by Ismail Gasprinski. A preference was given to the Oghuz dialect of the Yalıboylus, in order to not break the link between the Crimeans and the Turks of the Ottoman Empire. In 1928, the language was reoriented to the middle dialect spoken by the majority of the people.

In 1928, the alphabet was replaced with the Uniform Turkic Alphabet based on the Latin script. The Uniform Turkic Alphabet was replaced in 1938 by a Cyrillic alphabet. During the 1990s and 2000s, the government of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea under Ukraine encouraged replacing the script with a Latin version again, but the Cyrillic has still been widely used (mainly in published literature, newspapers and education). The current Latin-based Crimean Tatar alphabet is the same as the Turkish alphabet, with two additional characters: Ñ ñ and Q q. Currently, in the internationally unrecognized "Russian Republic of Crimea", all official communications and education in Crimean Tatar are conducted exclusively in the Cyrillic alphabet.[9]

Crimean Tatar was the native language of the poet Bekir Çoban-zade.

Since 2015 Crimea Realii (Qirim Aqiqat) starts series of video lessons "Elifbe" on Crimean language.

In 2016, the language was brought to international attention by the win of Ukrainian singer Jamala at that year's Eurovision Song Contest, with the song "1944" which featured a chorus fully in Crimean Tatar.

In 2016 Slava Vakarchuk, popular Ukrainian rock star, together with Iskandar Islamov sang song Sağındım in Lviv.

Phonology

Vowels

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UR | R | UR | R | |

| Close | i | y | ɯ | u |

| Mid/open | e | ø | ɑ | o |

The vowel system of Crimean Tatar is similar to some other Turkic languages.[10] Because high vowels in Crimean Tatar are short and reduced, /i/ and /ɯ/ are realized close to [ɪ], even though they are phonologically distinct.[11]

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Uvular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | t͡ʃ | k | q | |

| voiced | b | d | d͡ʒ | ɡ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | ||||||

| voiced | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | x | ||

| voiced | v | z | ɣ | ||||

| Trill | r | ||||||

| Approximants | l | j | |||||

In addition to these phonemes, Crimean also displays marginal phonemes that occur in borrowed words, especially palatalized consonants.[12]

The southern (coastal) dialect substitutes /x/ for /q/, e.g. standard qara 'black', southern xara.[13] At the same time the southern and some central dialects preserve glottal /h/ which is pronounced /x/ in the standard language.[13] The northern dialect on the contrary lacks /x/ and /f/, substituting /q/ for /x/ and /p/ for /f/.[13] The northern /v/ is usually [w], often in the place of /ɣ/, compare standard dağ and northern taw 'mountain' (also in other Oghuz and Kipchak languages, such as Azerbaijani: dağ and Kazakh: taw).

Writing systems

Crimean Tatar can be written in either the Cyrillic or Latin alphabets, both modified to the specific needs of Crimean Tatar, and either used respective to where the language is used. Under Ukrainian rule, the Latin alphabet was preferred, but upon Russia's annexation of the Crimea, Cyrillic became the sole official script.[9]

Arabic alphabet

Crimean Tatars used Arabic script from 16th century to 1928.

Latin alphabet

â is not considered to be a separate letter.

| a | b | c | ç | d | e | f | g | ğ | h | ı | i | j | k | l | m | n | ñ | o | ö | p | q | r | s | ş | t | u | ü | v | y | z |

| [a] | [b] | [dʒ] | [tʃ] | [d] | [e] | [f] | [ɡ] | [ɣ] | [x] | [ɯ] | [i], [ɪ] | [ʒ] | [k] | [l] | [m] | [n] | [ŋ] | [o] | [ø] | [p] | [q] | [r] | [s] | [ʃ] | [t] | [u] | [y] | [v], [w] | [j] | [z] |

Cyrillic alphabet

| а | б | в | г | гъ | д | е | ё | ж | з | и | й | к | къ | л | м | н | нъ | о | п | р | с | т | у | ф | х | ц | ч | дж | ш | щ | ъ | ы | ь | э | ю | я |

| [a] | [b] | [v],[w] | [ɡ] | [ɣ] | [d] | [ɛ],[jɛ] | [ø],[jø],[jo],[ʲo] | [ʒ] | [z] | [i],[ɪ] | [j] | [k] | [q] | [l],[ɫ] | [m] | [n] | [ŋ] | [o],[ø] | [p] | [r] | [s] | [t] | [u],[y] | [f] | [x] | [ts] | [tʃ] | [dʒ] | [ʃ] | [ʃtʃ] | [(.j)] | [ɯ] | [ʲ] | [ɛ] | [y],[jy],[ju],[ʲu] | [ʲa], [ja] |

гъ, къ, нъ and дж are separate letters (digraphs).

Legal status

The Crimean peninsula is internationally recognized as territory of Ukraine, but since the 2014 annexation by the Russian Federation is de facto administered as part of the RF.

According to Russian law, by the April 2014 constitution of the Republic of Crimea and the 2017 Crimean language law,[9] the Crimean Tatar language is a state language in Crimea alongside Russian and Ukrainian, while Russian is the state language of the Russian Federation, the language of interethnic communication, and required in public postings in the conduct of elections and referendums.[9]

In Ukrainian law, according to the constitution of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, as published in Russian by its Verkhovna Rada,[14] Russian and Crimean Tatar languages enjoy a "protected" (Russian: обеспечивается ... защита) status; every citizen is entitled, at his request (ходатайство), to receive government documents, such as "passport, birth certificate and others" in Crimean Tatar; but Russian is the language of interethnic communication and to be used in public life. According to the constitution of Ukraine, Ukrainian is the state language. Recognition of Russian and Crimean Tatar was a matter of political and legal debate.

Before the Sürgün, the 18 May 1944 deportation by the Soviet Union of Crimean Tatars to internal exile in Uzbek SSR, Crimean Tatar had an official language status in the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

References

- Crimean Tatar at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- The status of Crimea and of the city of Sevastopol is since March 2014 under dispute between Russia and Ukraine; Ukraine and the majority of the international community consider Crimea to be an autonomous republic of Ukraine and Sevastopol to be one of Ukraine's cities with special status, whereas Russia considers Crimea to be a federal subject of Russia and Sevastopol to be one of Russia's three federal cities like Russians cities Moscow and Saint Petersburg.

- "To which languages does the Charter apply?". European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Council of Europe. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2013-12-27. Retrieved 2014-04-03.

- "Reservations and Declarations for Treaty No.148 - European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages". Council of Europe. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Crimean Tatar". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Crimean Tatar language at Ethnologue (16th ed., 2009)

- Crimean Tatar language in danger, Avrupa Times, 02/19/2013

- "Tapani Salminen, UNESCO Red Book on Endangered Languages: Europe, September 1999". University of Helsinki, Finland. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- (in Russian) Закон Республики Крым «О государственных языках Республики Крым и иных языках в Республике Крым»

- Kavitskaya 2010, p. 6

- Kavitskaya 2010, p. 8

- Kavitskaya 2010, p. 10

- Изидинова 1997.

- "Конституция Автономной Республики Крым". Archived from the original on 2014-05-16. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

Bibliography

- Berta, Árpád (1998). "West Kipchak Languages". In Johanson, Lars; Csató, Éva Ágnes (eds.). The Turkic Languages. Routledge. pp. 301–317. ISBN 978-0-415-08200-6.

- Kavitskaya, Darya (2010). Crimean Tatar. Munich: Lincom Europa.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Изидинова, С. Р. (1997). "Крымскотатарский язык". Языки мира. Тюркские языки (in Russian).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Crimean Turkish edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |