Mesterolone

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Proviron, others |

| Synonyms | NSC-75054; SH-60723; SH-723; 1α-Methyl-4,5α-dihydrotestosterone; 1α-Methyl-DHT; 1α-Methyl-5α-androstan-17β-ol-3-one |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Androgen; Anabolic steroid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Low[1] |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.014.397 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H32O2 |

| Molar mass | 304.467 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Mesterolone, sold under the brand name Proviron among others, is an androgen and anabolic steroid (AAS) medication which is used mainly in the treatment of low testosterone levels.[1][2] It has also been used to treat male infertility, although this use is controversial.[1][3][4] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Side effects of mesterolone include symptoms of masculinization like acne, increased hair growth, voice changes, and increased sexual desire.[1] It has no risk of liver damage.[1][2] The drug is a synthetic androgen and anabolic steroid and hence is an agonist of the androgen receptor (AR), the biological target of androgens like testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT).[1][5] It has strong androgenic effects and weak anabolic effects, which make it useful for producing masculinization.[1] The drug has no estrogenic effects.[1][2]

Mesterolone was discovered and introduced for medical use in 1934.[1][6] In addition to its medical use, mesterolone has been used to improve physique and performance, although it is not commonly used for such purposes due to its weak anabolic effects.[1] The drug is a controlled substance in many countries and so non-medical use is generally illicit.[1][7]

Medical uses

Mesterolone is used in the treatment of androgen deficiency in male hypogonadism, anemia, and to support male fertility among other indications.[1][8][9] It has also been used to treat delayed puberty in boys.[10] Because it lacks estrogenic effects, mesterolone may be indicated for treating cases of androgen deficiency in which breast tenderness or gynecomastia is also present.[11] The drug is described as a relatively weak androgen with partial activity and is rarely used for the purpose of androgen replacement therapy, but is still widely used in medicine.[1][9][12][2]

Non-medical uses

Mesterolone has been used for physique- and performance-enhancing purposes by competitive athletes, bodybuilders, and powerlifters.[1]

Side effects

Side effects of mesterolone include virilization among others.[1]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Like other AAS, mesterolone is an agonist of the androgen receptor (AR).[1] It is not a substrate for 5α-reductase, as it is already 5α-reduced, and hence is not potentiated in so-called "androgenic" tissues such as the skin, hair follicles, and prostate gland.[1] Mesterolone is described as a very poor anabolic agent due to inactivation by 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD) in skeletal muscle tissue, similarly to DHT and mestanolone (17α-methyl-DHT).[1] In contrast, testosterone is a very poor substrate for 3α-HSD, and so is not similarly inactivated in skeletal muscle.[1] Because of its lack of potentiation by 5α-reductase in "androgenic" tissues and its inactivation by 3α-HSD in skeletal muscle, mesterolone is relatively low in both its androgenic potency and its anabolic potency.[1] However, it does still show a greater ratio of anabolic activity to androgenic activity relative to testosterone.[1]

Mesterolone is not a substrate for aromatase, and so cannot be converted into an estrogen.[1] As such, it has no propensity for producing estrogenic side effects such as gynecomastia and fluid retention.[1] It also has no progestogenic activity.[1]

Because mesterolone is not 17α-alkylated, it has little or no potential for hepatotoxicity.[1] However, its risk of deleterious effects on the cardiovascular system is comparable to that of several other oral AAS.[1]

Pharmacokinetics

The C1α methyl group of mesterolone inhibits its hepatic metabolism and thereby confers significant oral activity, although its oral bioavailability is still much lower than that of 17α-alkylated AAS.[1] In any case, mesterolone is one of the few non-17α-alkylated AAS that is active with oral ingestion.[1] Uniquely among AAS, mesterolone has very high affinity for human serum sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), about 440% that of DHT in one study and 82% of that of DHT in another study.[13][1][14] As a result, it may displace endogenous testosterone from SHBG and thereby increase free testosterone concentrations, which may in part be involved in its effects.[1]

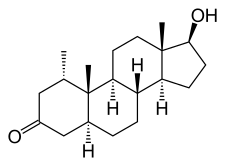

Chemistry

Mesterolone, also known as 1α-methyl-4,5α-dihydrotestosterone (1α-methyl-DHT) or as 1α-methyl-5α-androstan-17β-ol-3-one, is a synthetic androstane steroid and derivative of DHT.[15][16][1] It is specifically DHT with a methyl group at the C1α position.[15][16][1] Closely related AAS include metenolone and its esters metenolone acetate and metenolone enanthate.[15][16][1] The antiandrogen rosterolone (17α-propylmesterolone) is also closely related to mesterolone.[17]

History

Mesterolone was synthesized and introduced for medical use in 1934 and was the first AAS to be marketed.[1][6] It was followed by methyltestosterone in 1936 and testosterone propionate in 1937.[6][18][1][19] The drug continues to be widely available and used today.[1][20]

Society and culture

Generic names

Mesterolone is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, BAN, and DCIT, while mestérolone is its DCF.[15][16][21][20]

Brand names

Mesterolone is marketed mainly under the brand name Proviron.[15][16][20][1]

Availability

Mesterolone is available widely throughout the world, including in the United Kingdom, Australia, and South Africa, as well as many non-English-speaking countries.[16][20] It is not available in the United States, Canada, or New Zealand.[16][20] The drug has never been marketed in the United States.[6]

Legal status

Mesterolone, along with other AAS, is a schedule III controlled substance in the United States under the Controlled Substances Act and a schedule IV controlled substance in Canada under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.[7][22]

Research

In one small scale clinical trial of depressed patients, an improvement of symptoms which included anxiety, lack of drive and desire was observed.[23] In patients with dysthymia, unipolar, and bipolar depression significant improvement was observed.[23] In this series of studies, mesterolone lead to a significant decrease in luteinizing hormone and testosterone levels.[23] In another study, 100 mg mesterolone cipionate was administered twice monthly.[24] With regards to plasma testosterone levels, there was no difference between the treated versus untreated group, and baseline luteinizing hormone levels were minimally affected.[24]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 William Llewellyn (2011). Anabolics. Molecular Nutrition Llc. pp. 641–. ISBN 978-0-9828280-1-4.

- 1 2 3 4 E. Nieschlag; H. M. Behre (1 April 2004). Testosterone: Action, Deficiency, Substitution. Cambridge University Press. pp. 411–. ISBN 978-1-139-45221-2.

- ↑ T.B. Hargreave (6 December 2012). Male Infertility. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 398–399. ISBN 978-1-4471-1029-3.

- ↑ Larry I. Lipshultz; Stuart S. Howards; Craig S. Niederberger (24 September 2009). Infertility in the Male. Cambridge University Press. pp. 445–446. ISBN 978-0-521-87289-8.

- ↑ Kicman AT (2008). "Pharmacology of anabolic steroids". Br. J. Pharmacol. 154 (3): 502–21. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.165. PMC 2439524. PMID 18500378.

- 1 2 3 4 Alexandre Hohl (6 April 2017). Testosterone: From Basic to Clinical Aspects. Springer. pp. 204–. ISBN 978-3-319-46086-4.

- 1 2 Steven B. Karch, MD, FFFLM (21 December 2006). Drug Abuse Handbook, Second Edition. CRC Press. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-1-4200-0346-8.

- ↑ Gautam N. Allahbadia; Rita Basuray Das (12 November 2004). The Art and Science of Assisted Reproductive Techniques. CRC Press. pp. 824–. ISBN 978-0-203-64051-7.

- 1 2 Kenneth L. Becker (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1186–. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2.

- ↑ I. Hart; R.W. Newton (6 December 2012). Endocrinology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-94-010-9298-2.

- ↑ Corona G, Rastrelli G, Vignozzi L, Maggi M (2012). "Emerging medication for the treatment of male hypogonadism". Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 17 (2): 239–59. doi:10.1517/14728214.2012.683411. PMID 22612692.

- ↑ Nieschlag E, Behre HM, Bouchard P, et al. (2004). "Testosterone replacement therapy: current trends and future directions". Hum. Reprod. Update. 10 (5): 409–19. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmh035. PMID 15297434.

- ↑ Saartok T, Dahlberg E, Gustafsson JA (1984). "Relative binding affinity of anabolic-androgenic steroids: comparison of the binding to the androgen receptors in skeletal muscle and in prostate, as well as to sex hormone-binding globulin". Endocrinology. 114 (6): 2100–6. doi:10.1210/endo-114-6-2100. PMID 6539197.

- ↑ Pugeat MM, Dunn JF, Nisula BC (July 1981). "Transport of steroid hormones: interaction of 70 drugs with testosterone-binding globulin and corticosteroid-binding globulin in human plasma". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 53 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1210/jcem-53-1-69. PMID 7195405.

- 1 2 3 4 5 J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 775–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 656–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ↑ Brooks, J. R.; Primka, R. L.; Berman, C; Krupa, D. A.; Reynolds, G. F.; Rasmusson, G. H. (1991). "Topical anti-androgenicity of a new 4-azasteroid in the hamster". Steroids. 56 (8): 428–33. doi:10.1016/0039-128x(91)90031-p. PMID 1788861.

- ↑ N.A.R.D. journal. National Association of Retail Druggists. July 1956.

- ↑ William Llewellyn (2011). Anabolics. Molecular Nutrition Llc. pp. 413, 426, 607. ISBN 978-0-9828280-1-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 https://www.drugs.com/international/mesterolone.html

- ↑ I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- ↑ Linda Lane Lilley; Julie S. Snyder; Shelly Rainforth Collins (5 August 2016). Pharmacology for Canadian Health Care Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-1-77172-066-3.

- 1 2 3 Itil TM, Michael ST, Shapiro DM, Itil KZ (June 1984). "The effects of mesterolone, a male sex hormone in depressed patients (a double blind controlled study)". Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 6 (6): 331–7. PMID 6431212.

- 1 2 Kövary PM, Lenau H, Niermann H, Zierden E, Wagner H (May 1977). "Testosterone levels and gonadotrophins in Klinefelter's patients treated with injections of mesterolone cipionate". Arch Dermatol Res. 258 (3): 289–94. doi:10.1007/bf00561132. PMID 883846.

External links

Further reading

- Morrison, Mary Chase (2000). Hormones, Gender and the Aging Brain: The Endocrine Basis of Geriatric Psychiatry. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 134. ISBN 0-521-65304-5.