LGBT rights in India

| LGBT rights in India | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) Area controlled by India shown in dark green; claimed but uncontrolled regions shown in light green. | |

| Same-sex sexual intercourse legal status | Legal since 2018,[1] unclear in Jammu and Kashmir[2] |

| Gender identity/expression | Transgender people have a constitutional right to change their legal gender and third gender is recognised |

| Military service | No |

| Discrimination protections | Constitutional protections |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | No recognition |

| Adoption | No |

| Part of a series on |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights |

|---|

|

|

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people in India face legal and social difficulties not experienced by non-LGBT persons. Sexual activity between people of the same gender is legal but same-sex couples cannot legally marry or obtain civil partnerships.[3] On 6 September 2018, the Supreme Court of India decriminalised homosexuality by declaring Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code unconstitutional.[1] The Court unanimously ruled that individual autonomy, intimacy, and identity are protected fundamental rights.

Since 2014, transgender people in India have been allowed to change their gender without sex reassignment surgery, and have a constitutional right to register themselves under a third gender. Additionally, some states protect hijras, a traditional third gender population in South Asia, through housing programmes, welfare benefits, pension schemes, free surgeries in government hospitals and others programmes designed to assist them. There are approximately 4.8 million transgender people in India.[4]

Over the past decade, LGBT people have gained more and more tolerance in India, especially in large cities.[5] Nonetheless, most LGBT people in India remain closeted, fearing discrimination from their families, who might see homosexuality as shameful.[5] Reports of honour killings, attacks, torture, and beatings of members of the LGBT community are not uncommon in India.[6][7][8] Discrimination and ignorance are particularly present in rural areas, where LGBT people often face rejection from their families and forced opposite-sex marriages.[9]

Law regarding same-sex sexual activity

History

The Khajuraho temples, famous for their erotic sculptures, contain several depictions of homosexual activity. Historians have long argued that pre-colonial Indian society did not criminalise same-sex relationships, nor did it view such relations as immoral or sinful. Transgender individuals held high positions in courts of Mughal rulers in the 16th and 17th centuries. Hinduism, India's largest religion, has traditionally portrayed homosexuality as natural and joyful, though some Hindu texts do contain injunctions against homosexuality. Hinduism also acknowledges a third gender known as hijra. There are multiple characters in the Mahabharata who change genders such as Shikhandi who is born female but identifies as male and eventually marries a woman. Bahuchara Mata is the goddess of fertility, worshipped by hijras as their patroness. Modern societal homophobia was introduced to India by the European colonisers and the subsequent enactment of Section 377 by the British, which stood for more than 70 years after Indian independence.[10]

The Goa Inquisition once prosecuted the capital crime of sodomy in Portuguese India,[11][12] but not lesbian activity.[13]

During the Mughal Empire, a number of the preexisting Delhi Sultanate laws were combined into the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri, mandating a common set of punishments for zina (unlawful intercourse).[14] These could include 50 lashes for a slave, 100 for a free infidel, or death by stoning for a Muslim.[15] In practice, however, this stipulation was largely ignored, for the elite at least. Homoeroticism was quite common in Mughal court life. Mughal Emperor Babur was known to have a crush on a boy, and recorded it in his memoirs. Other prominent Mughal men who engaged in homosexuality include Ali Quli Khan, and poet Sarmad Kashani who had such a crush on a Hindu boy that he went to his home naked. In contrast, homosexual acts were regarded as taboo among the common people.[16][17][18][19][20]

The British Raj criminalised anal sex and oral sex (for both heterosexuals and homosexuals) under Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which entered into force in 1861. This made it an offence for a person to voluntarily have "carnal intercourse against the order of nature."

In 1884, a court in north India, ruling on the prosecution of a hijra, commented that a physical examination of the accused revealed she "had the marks of a habitual catamite" and commended the police's desire to "check these disgusting practices".[21]

Contemporary times

In 2003, the Indian Government said that legalising homosexuality would "open the floodgates of delinquent behaviour".[21]

In 2009, the Delhi High Court decision in Naz Foundation v. Govt. of NCT of Delhi found Section 377 and other legal prohibitions against private, adult, consensual, and non-commercial same-sex conduct to be in direct violation of fundamental rights provided by the Indian Constitution. Section 377 stated that: "Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal, shall be punished with [imprisonment for life], or with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to ten years, and shall also be liable to fine," with the added explanation that: "Penetration is sufficient to constitute the carnal intercourse necessary to the offence described in this section."[22]

According to a previous ruling by the Indian Supreme Court, decisions of a high court on the constitutionality of a law apply throughout India, and not just to the state over which the high court in question has jurisdiction.[23]

There have been incidents of harassment of LGBT groups by authorities under the law.[24]

On 23 February 2012, the Ministry of Home Affairs expressed its opposition to the decriminalisation of homosexual activity, stating that in India, homosexuality is seen as being immoral.[25] The Central Government reversed its stance on 28 February 2012, asserting that there was no legal error in decriminalising homosexual activity. The shift in stance resulted in two judges of the Supreme Court reprimanding the Central Government for frequently changing its approach to the issue.[26]

On 11 December 2013, the Supreme Court set aside the 2009 Delhi High Court order decriminalising consensual homosexual activity within its jurisdiction.[27][28][29][30][31]

Human Rights Watch expressed concerns that the Supreme Court ruling would render same-sex couples vulnerable to police harassment,[32] stating that "the Supreme Court's ruling is a disappointing setback to human dignity, and the basic rights to privacy and non-discrimination"[33] The Naz Foundation stated that it would file a petition for review of the court's decision.[34] Activist group Kavi's Humsafar Trust have reported that two-fifths of homosexuals in the country had faced blackmail after the 2013 ruling.[10]

On 28 January 2014, the Supreme Court of India dismissed the review petition filed by the Central Government, the Naz Foundation and several others against its 11 December verdict on Section 377.[35] The bench explained the ruling by claiming that: "While reading down Section 377, the High Court overlooked that a minuscule fraction of the country’s population constitutes lesbians, gays, bisexuals or transgender people, and in the more than 150 years past, less than 200 persons have been prosecuted for committing offence under Section 377, and this cannot be made a sound basis for declaring that Section ultra vires Articles 14, 15 and 21."[36]

On 18 December 2015, Shashi Tharoor, a member of the Indian National Congress party, introduced a bill for the repeal of Section 377, but it was rejected in the House by a vote of 71-24. Shashi Tharoor is planning to re-introduce the bill.[37]

On 2 February 2016, the Supreme Court decided to review the criminalisation of homosexual activity.[38] In August 2017, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the right to individual privacy is an intrinsic and fundamental right under the Indian Constitution. The Court also ruled that a person's sexual orientation is a privacy issue, giving hopes to LGBT activists that the Court would soon strike down Section 377.[39]

In January 2018, the Supreme Court agreed to refer the question of Section 377's validity to a large bench,[40] and heard several petitions on 1 May 2018.[41] In response to the court's request for its position on the petitions,[42] the Government announced that it would not oppose the petitions, and would leave the case "to the wisdom of the court".[43] A hearing began on 10 July 2018,[44][45] with a verdict expected before October 2018.[46] Activists view the case as the most significant and "greatest breakthrough for gay rights since the country's independence", and it could have far-reaching implications for other Commonwealth countries that still outlaw homosexuality.[43]

On 6 September 2018, the Supreme Court issued its verdict.[1] The Court unanimously ruled that Section 377 is unconstitutional as it infringed on the fundamental rights of autonomy, intimacy and identity, thus legalising homosexuality in India.[47] The Court explicitly overturned its 2013 judgement.

Criminalising carnal intercourse is irrational, arbitrary and manifestly unconstitutional.

History owes an apology to these people and their families. Homosexuality is part of human sexuality. They have the right of dignity and free of discrimination. Consensual sexual acts of adults are allowed for [the] LGBT community.

— Justice Indu Malhotra

It is difficult to right a wrong by history. But we can set the course for the future. This case involves much more than decriminalizing homosexuality. It is about people wanting to live with dignity.

— Justice Dhananjaya Y. Chandrachud

Furthermore, it ruled that any discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is a violation of the Indian Constitution:[49]

Sexual orientation is one of the many biological phenomena which is natural and inherent in an individual and is controlled by neurological and biological factors. The science of sexuality has theorized that an individual exerts little or no control over who he/she gets attracted to. Any discrimination on the basis of one‘s sexual orientation would entail a violation of the fundamental right of freedom of expression.

The Supreme Court also directed the Government to take all measures to properly broadcast the fact that homosexuality is not a criminal offence, to create public awareness and eliminate the stigma members of the LGBT community face, and to give the police force periodic training to sensitise them about the issue.[50][51][52]

Legal experts have urged the Government to pass legislation reflecting the decision, and frame laws to allow same-sex marriage, adoption by same-sex couples and inheritance rights.[53]

Sex with minors, non-consensual sex (rape) and bestiality remain criminal offences. The Supreme Court ruling may not extend to the state of Jammu and Kashmir, which is governed by its own criminal law, the Ranbir Penal Code (RPC).[2] Legal opinion is divided on whether the Supreme Court judgment applies to the state or not. Per a 1995 judgment of the state High Court, when an IPC (Indian Penal Code) provision is struck down on grounds of violating the Constitution, its corresponding provision in the Ranbir Penal Code too would be struck down.[54] However, it has yet to be determined if Section 377 of the RPC is identical to its IPC version. LGBT activists in Jammu and Kashmir have already announced their intention to challenge the RPC.[55]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

.jpg)

Same-sex marriages are not legally recognised in India nor are same-sex couples offered limited rights such as a civil union or a domestic partnership. In 2011, a Haryana court granted legal recognition to a same-sex marriage, involving two women.[3] After marrying, the couple began to receive threats from friends and relatives in their village. The couple eventually won family approval.[56]

Their lawyer said the court had served notice on 14 of Veena's relatives and villagers who had threatened them with "dire consequences". Haryana has been the centre of widespread protests by villagers who believe their village councils or khaps should be allowed to impose their own punishments on those who disobey their rulings or break local traditions – mainly honour killings of those who marry within their own gotra or sub-caste, regarded in the state as akin to incest. Deputy Commissioner of Police Dr. Abhe Singh told The Daily Telegraph: "The couple has been shifted to a safe house and we have provided adequate security to them on the court orders. The security is provided on the basis of threat perception and in this case the couple feared that their families might be against the relationship."[57]

In October 2017, a group of citizens proposed a draft of a new Uniform Civil Code that would legalise same-sex marriage to the Law Commission of India.[58]

It defines marriage as "the legal union as prescribed under this Act of a man with a woman, a man with another man, a woman with another woman a transgender with another transgender or a transgender with a man or a woman. All married couples in partnership entitled to adopt a child. Sexual orientation of the married couple or the partners not to be a bar to their right to adoption. Non-heterosexual couples will be equally entitled to adopt a child".[59]

There are currently several same-sex marriage petitions pending with the courts.[53]

Discrimination protections

Article 15 of the Constitution of India states that:[60]

15. Prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth

- (1) The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them

- (2) No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them, be subject to any disability, liability, restriction or condition with regard to

- (a) access to shops, public restaurants, hotels and palaces of public entertainment; or

- (b) the use of wells, tanks, bathing ghats, roads and places of public resort maintained wholly or partly out of State funds or dedicated to the use of the general public

- (a) access to shops, public restaurants, hotels and palaces of public entertainment; or

The Supreme Court has ruled that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is prohibited by the Indian Constitution.[1] Individuals who face discrimination because of their sexual orientation can now mount a challenge in a court of law.[53]

Transgender rights

South Asia (modern-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal) has traditionally recognised a third gender population, considered by society as neither male or female. Such individuals are known as hijras or alternatively hijadas (Hindi: हिजड़ा; Bengali: হিজড়া; Nepali and Marathi: हिजडा). In Telugu, they are referred to as napunsakudu (నపుంసకుడు), in Urdu as khwaja sara (ہیجڑا), in Gujarati as pavaiyaa (પાવૈયા), in Tamil as thirunangayar/thirunangai (திருநங்கை), in Punjabi as khusra (ਖੁਸਰਾ), in Odia as napunsak (ନପୁଂସକ), in Sindhi as khadro (کدڙو), in Malayalam as sandan (ഷണ്ഡന്), in Kannada as chhakka (ಚಕ್ಕ), in Konkani as izddo, in Manipuri as nupi manbi, in Kashmiri as napumsakh (नपुंसख्), in Assamese as npunnsk (নপুংসক), in Santali as cakra, in Sanskrit as klība (क्लीब), and in Mizo as mil tilreh.[61][62][63][64][65] In English language publications, these terms are given to eunuchs, intersex people or transgender people.

Hijras were legally granted voting rights as a third sex in 1994.[66] Due to alleged legal ambiguity of the procedure, Indian transgender individuals have difficulties accessing safe medical facilities for surgery.[67] On 15 April 2014, the Supreme Court of India declared transgender people a socially and economically backward class entitled to reservations in education and jobs, and also directed union and state governments to frame welfare schemes for them.[68] The Court ruled that transgender people have a fundamental constitutional right to change their gender without any sort of surgery, and called on the Government to ensure equal treatment for transgender people. The Court also right that the Indian Constitution mandates the recognition of a third gender on official documents.[69] In light of the ruling, government documents, such as voter ID cards, passports and bank forms, have started providing a third gender option alongside male (M) and female (F), usually designated "other" (O), "third gender" (TG) or "transgender" (T).[70]

In 2013, transgender and gender activists S. Swapna and Gopi Shankar Madurai from Srishti Madurai staged a protest in the Madurai collectorate on 7 October 2013 demanding reservation and to permit alternate genders to appear for examinations conducted by TNPSC, UPSC, SSC and Bank exams.[71][72] Swapna, incidentally, had successfully moved the Madras High Court in 2013 seeking permission to write the TNPSC Group II exam as a female candidate. Swapna is the first transgender person to clear TNPSC Group IV exams.[73]

On 24 April 2015, the Rajya Sabha unanimously passed the Rights of Transgender Persons Bill, 2014 guaranteeing rights and entitlements, reservations in education and jobs (2% reservation in government jobs), legal aid, pensions, unemployment allowances and skill development for transgender people. It also contains provisions to prohibit discrimination in employment as well as prevent abuse, violence and exploitation of transgender people. The bill also provides for the establishment of welfare boards at the centre and state level as well as for transgender rights courts. The bill was introduced by DMK MP Tiruchi Siva, and marked the first time the upper house had passed a private member's bill in 45 years. However, the bill contains several anomalies and a lack of clarity on how various ministries will coordinate to implement its provisions.[74] The bill is still pending in the lower house.

Social Justice and Empowerment Minister Thaawar Chand Gehlot stated on 11 June 2015 that the Government would introduce a new comprehensive bill for transgender rights in the Monsoon session of Parliament. The bill would be based on the study on transgender issues conducted by a committee appointed on 27 January 2014. According to Gehlot, the Government intends to provide transgender people with all rights and entitlements currently enjoyed by scheduled castes and scheduled tribes.[75]

The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill, 2016, which was initially introduced to Parliament in August 2016, was re-introduced to Parliament in late 2017.[4] Some transgender activists have opposed the bill because it does not address issues such as marriage, adoption and divorce for transgender people. Akkai Padmashali criticised the bill's definition of transgenderism, which states that transgender people are "based on the underlying assumption of biological determinism".[76]

State laws

The states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala were the first Indian states to introduce a transgender welfare policy. According to the transgender welfare policy, transgender people can access free sex reassignment surgery (SRS) in government hospitals (only for male-to-female); free housing program; various citizenship documents; admission in government colleges with full scholarship for higher studies; alternative sources of livelihood through formation of self-help groups (for savings) and initiating income-generation programmes (IGP). Tamil Nadu was also the first state to form a transgender welfare board with representatives from the transgender community. In 2016, Kerala started implementing free surgery in government hospitals.[77][78]

In July 2016, the state of Odisha enacted welfare benefits for transgender people, giving them the same benefits as those living below the poverty line. This was aimed at improving their overall social and economic status, according to the Odisha Department of Social Security.[79]

In April 2017, the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation instructed states to allow transgender people to use the public toilet of their choice.[80]

In October 2017, the Karnataka Government issued the "State Policy for Transgenders, 2017", with the aim of raising awareness of transgender people within all educational institutions in the state. Educational institutions will address issues of violence, abuse and discrimination against transgender people. It also established a monitoring committee designed with investigating reports of discrimination.[81]

On 28 November 2017, N. Chandrababu Naidu, the Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh, announced the enactment of pension plans for transgender people.[82]. On 16 December 2017, the Andhra Cabinet passed the policy. According to the policy, the State Government will provide an amount of ₹1,500 per month to each transgender person above the age of 18 for social security pensions. In addition, the Government will construct special toilets in public places, like malls and cinema halls, for transgender people.[83]

In January 2018, the Kashmiri Finance Minister introduced a proposal to the Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly that would grant transgender people free life and medical insurance, and a monthly sustenance pension for those aged 60+ and registered with the Social Welfare Department. Transgender activists have criticised aspects of the bill, including its requirement to establish medical boards to issue "transgender certificates".[84][85]

Third-gender literature and studies

Vaadamalli by novelist Su. Samuthiram is the first Tamil novel about the local aravani community in Tamil Nadu, published in 1994. Later, transgender activist A. Revathi became the first hijra to write about hijra issues and gender politics in Tamil. Her works have been translated into more than eight languages and act as a primary resource on gender studies in Asia. Her book is part of a research project for more than 100 universities. She is the author of Unarvum Uruvamum (Feelings of the Entire Body), the first of its kind in English from a member of the hijra community.[86][87] She also acted and directed several stage plays on gender and sexuality issues in Tamil and Kannada. The Truth about Me: A Hijra Life Story by A. Revathi is part of the syllabus for final year students of The American College in Madurai. The American College is the first college in India to introduce third gender literature and studies with research-oriented seminars.[88] Later, Naan Saravanan's Alla (2007) and Vidya's I Am Vidya (2008) were among early transwoman autobiographies.[89][90]

Conversion therapy

In February 2014, the Indian Psychiatric Society (IPS) issued a statement, in which it stated that there is no evidence to prove that homosexuality is unnatural: "Based on existing scientific evidence and good practice guidelines from the field of psychiatry, the Indian Psychiatric Society would like to state that there is no evidence to substantiate the belief that homosexuality is a mental illness or a disease."[91]

Despite this statement from the IPS, conversion therapies are still performed in India. These practices usually involve electroconvulsive therapy (which may lead to memory loss), hypnosis, the administration of nausea-inducing drugs, or more commonly talk therapy where the individual is told that homosexuality is caused by "insufficient male affirmation in childhood" or "an uncaring father and an overbearing mother". Conversion therapy can lead to depression, anxiety, seizures, drug use and suicidal tendencies for the individuals invloved.[92]

In June 2018, IPS reiterated its stance on homosexuality saying: "Certain people are not cut out to be heterosexual and we don’t need to castigate them, we don’t need to punish them, to ostracize them".[93]

Living conditions

There are many avenues for the LGBT community in metro cities for meeting and socialising, although not very openly. These include GayBombay, Good as You, HarmlessHugs. Recently, a queer dating platform named Amour Queer Dating was launched to help LGBT people find long-term partners.[95]

There have many reports of abuse, harrasment and violence over the years directed against LGBT people. In 2003, a hijra was gang-raped in Bangalore, and then gang-raped by the police. Testimonies provided to the Delhi High Court in 2007 documented how a gay man abducted by the police in Delhi was raped by police officials for several days and forced to sign a "confession" saying "I am a gandu [a derogatory term, meaning one who has anal sex]". In 2011, a Haryana lesbian couple was murdered by their nephews for being in an "immoral" relationship.[21] According to reports from activist group Kavi's Humsafar Trust, two-fifths of homosexuals in the country had faced blackmail after the 2013 Supreme Court ruling.[10] Suicide attempts are common. In early 2018, a lesbian couple committed suicide and left a note reading: "We have left this world to live with each other. The world did not allow us to stay together."[21]

In February 2017, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare unveiled resource material relating to health issues to be used as a part of a nationwide adolescent peer-education plan called Saathiya. Among other subjects, the material discusses homosexuality. The material states, "Yes, adolescents frequently fall in love. They can feel attraction for a friend or any individual of the same or opposite sex. It is normal to have special feelings for someone. It is important for adolescents to understand that such relationships are based on mutual consent, trust, transparency and respect. It is alright to talk about such feelings to the person for whom you have them but always in a respectful manner."[96][97]

In 2017, Delhi held its tenth pride parade, attended by hundreds of people.[5] Chennai has held pride parades since 2009,[98] while Goa held its first pride parade in October 2017.[99] Bhubaneswar organised its first in September 2018.[100]

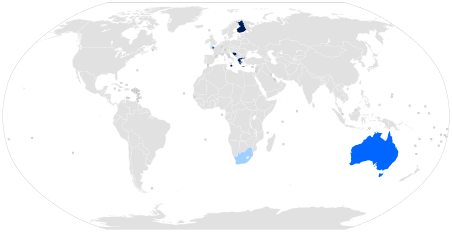

On 17 May 2018, the International Day Against Homophobia, activities were held throughout the country, including in Delhi, Mumbai, Kolhapur, Thiruvananthapuram and Lucknow. Numerous foreign embassies (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Costa Rica, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States) expressed support for LGBT rights in India, and reaffirmed their countries' commitement to promote human rights.[101]

Politics

The All India Hijra Kalyan Sabha fought for over a decade to get voting rights, which they finally got in 1994. In 1996, Kali stood for office in Patna under the then Judicial Reform Party. Munni ran in the elections as well for South Mumbai that year. They both lost.[102]

After the defeat of Kali and Munni, three years later, Kamla Jaan ran and won the position of the Mayor of Katni. Later, Shabnam Mausi was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Madhya Pradesh in 2002. Over the next few years, multiple other transgender candidates won office. These include Heera who won a seat at the City Council of Jabalpur and Gulshan who was elected to the City Council in Bina Etawa. In December 2000, Asha Devi became the Mayor of Gorakhpur, and Kallu Kinnar was elected to the City Council in Varanasi.

Shabnam Mausi is the first transgender Indian to be elected to public office. She was an elected member of the Madhya Pradesh State Legislative Assembly from 1998 to 2003. In 2000, Shabnam Mausi became India's first eunuch MP. Transgender people were granted voting rights in 1994. In 2003, hijras in Madhya Pradesh announced the establishment of their own political party called "Jeeti Jitayi Politics" (JJP), which literally means "politics that has already been won". The party also has released an eight-page election manifesto which it claims outlines why it is different from mainstream political parties.[103]

Kalki Subramaniam is a transgender rights activist, writer and an actor. In the 2011 assembly elections in Tamil Nadu, Kalki tried in vain to get a DMK ticket.[104] In March 2014, Kalki announced in Puducherry that she would contest a seat in an election in the Villupuram constituency in neighbouring Tamil Nadu.[105]

On 4 January 2015, independent transgender candidate Madhu Bai Kinnar was elected as the Mayor of Raigarh, Chhattisgarh.[106][107][108][109]

Manabi Bandopadhyay became India's first transgender college principal on 9 June 2015 when she assumed the role of principal of the Krishnagar Women's College in Nadia district, West Bengal.[110][111]

On 5 November 2015, K. Prithika Yashini became the first transgender police officer in the state of Tamil Nadu. At the time, the Tamil Nadu police had three transgender constables, but Yashini became the first transgender person to hold the rank of officer in the state.[112]

On 12 February 2017, two transgender people were appointed by the Kolhapur District Legal Services Authority (KDLSA) as panel members for the local Lok Adalat (People's Court). 30 panels were appointed to settle general local disputes that arise within the community. Members of the KDLSA have stated: "Our main achievement was inclusion of transgenders as panelist in Lok Adalat. As per the Supreme Court's judgment, transgenders must be recognised as the third gender in our country. As per the norm, we have put in efforts and included two transgenders Mayuri Alawekar and Yuvraj Alavankar as panel members."[113]

In July 2017, Joyita Mondal was appointed to the Islampur Lok Adalat, becoming West Bengal's first transgender judge.[114] In 2018, Swati Bidham Baruah became the first transgender judge in Assam. Swati, founder of the All Assam Transgender Association, was appointed to the Guwahati Lok Adalat.[115]

Intersex rights

Intersex issues in India may often be perceived as third gender issues. The most well-known third gender groups in India are the hijras. After interviewing and studying hijras for many years, Serena Nanda writes in her book, Neither Man Nor Woman: The hijras of India, as follows: "There is a widespread belief in India that hijras are born hermaphrodites [intersex] and are taken away by the hijra community at birth or in childhood, but I found no evidence to support this belief among the hijras I met, all of whom joined the community voluntarily, often in their teens."[116] Sangam literature uses the word pedi to refer to people born intersex, but the indigenous gender minorities in India were clear about intersex people and referred to them as mabedi usili and gave a distinct identity to denote them.[117] Also, there is evidence that few intersex people choose to identify as transgender.[118]

Physical integrity and bodily autonomy

Intersex persons are not protected from violations to physical integrity and bodily autonomy.

Cases of infanticide have been reported involving infants with obvious intersex conditions at birth, along with a failure to thrive by infants assigned female.[119] Medical reports suggest that parents in India prefer to assign infants with intersex conditions as male, with surgical interventions taking place when parents can afford them.[120][121][122]

In a reply to a letter from an intersex rights activist Gopi Shankar Madurai, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India replied that "Any kind of invasive medical procedure including sex reassignment surgeries are done only after thorough assessment of the patient, obtaining justification for the procedure planned to be conducted with the help of appropriate diagnostic test and only after taking a written consent of the patient/guardian".[123]

Besides male and female, Indian passports are avaiable with an "O" sex descriptor (for "Other").[70]

Protection from discrimination

Multiple Indian athletes have been subjected to humiliation, discrimination and loss of work and medals following sex verification.[124] Middle-distance runner Santhi Soundarajan, who won the silver medal in 800 m at the 2006 Asian Games in Doha, Qatar, was stripped of her medal,[125] and later attempted suicide.[126][127] Track athlete Pinki Pramanik was accused by a female roommate of rape and later charged, gender tested and declared male, though she and other medical experts dispute these claims.[128] Indian athlete Dutee Chand won a case against the IAAF in 2015, enabling women athletes with high testosterone levels to compete as women, on the basis that there is no clear evidence of performance benefits.[129] In 2016, some sports clinicians stated: "One of the fundamental recommendations published almost 25 years ago ... that athletes born with a disorder of sex development and raised as females be allowed to compete as women remains appropriate".[130]

Public opinion

Public opinion regarding LGBT rights in India is complex. According to a 2016 poll by the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, 35% of Indian people were in favor of legalising same-sex marriage, with a further 35% opposed.[131] A survey by the Varkey Foundation found that support for same-sex marriage was higher among 18-21 year olds at 53%.[132]

According to a 2017 poll carried out by ILGA, 58% of Indians agreed that gay, lesbian and bisexual people should enjoy the same rights as straight people, while 30% disagreed. Additionally, 59% agreed that they should be protected from workplace discrimination. 39% of Indians, however, said that people who are in same-sex relationships should be charged as criminals, while a plurality of 44% disagreed. As for transgender people, 66% agreed that they should have the same rights, 62% believed they should be protected from employment discrimination and 60% believed they should be allowed to change their legal gender.[133]

Notable Indian LGBTI rights activists

| S. No. | Name | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anjali Ameer | Malayalam film actress |

| 2 | Manabi Bandyopadhyay | India's first openly transgender college principal and first transgender person to hold a PhD |

| 3 | Vinay Chandran | Gay and human rights activist |

| 4 | Bobby Darling | Transsexual actress and vocal supporter of LGBT rights |

| 5 | Tista Das | Transsexual activist |

| 6 | Sushant Divgikar | Mr. India Gay 2014 |

| 7 | Pablo Ganguli | Cultural entrepreneur, artist, director and impresario |

| 8 | Rituparno Ghosh | Popular filmmaker, winner of 11 Indian National Film Awards |

| 9 | Anjali Gopalan | Human rights activist |

| 10 | Andrew Harvey | Author, religious scholar and teacher of mystic traditions |

| 11 | Harish Iyer | Activist, columnist and blogger |

| 12 | Celina Jaitley | Miss India 2001 |

| 13 | Firdaus Kanga | Writer and actor |

| 14 | Karpaga | First trans person in India to perform a leading role in a mainstream movie |

| 15 | Saleem Kidwai | Writer |

| 16 | Agniva Lahiri | Social activist (PLUS Kolkata) |

| 17 | Nolan Lewis | Mr. India Gay 2013 |

| 18 | Leena Manimekalai | Poet, writer and film maker |

| 19 | Shabnam Mausi | First openly trans person to participate in Indian elections |

| 20 | Hoshang Merchant | Teacher, poet and critic |

| 21 | Ismail Merchant | Film producer and director |

| 22 | Raul Patil | Mr. India Gay 2011 |

| 23 | Zoltan Parag | Mr. India Gay 2008 |

| 24 | Onir | Award-winning film director |

| 25 | Sridhar Rangayan | Film maker, and founder and festival director of Kasish Mumbai International Queer Film Festival |

| 26 | R. Raj Rao | Writer, professor of literature |

| 27 | A. Revathi | Actor, artist, writer and theater activist |

| 28 | Wendell Rodricks | Fashion designer and choreographer |

| 29 | Ashok Row Kavi | Founder of Humsafur Trust |

| 30 | Aishwarya Rutuparna Pradhan | First openly transgender civil servant and Odisha Financial Services officer |

| 31 | Nishit Saran | Filmmaker and gay rights activist |

| 32 | Vikram Seth | Writer |

| 33 | Parvez Sharma | Writer and documentary filmmaker |

| 34 | Gopi Shankar Madurai | Genderqueer activist, recipient of the Commonwealth Youth Worker Asia Finalist Award and founder of Srishti Madurai[134][135][136][137] |

| 35 | Manvendra Singh Gohil | Hereditary Prince of Rajpipla |

| 36 | Ramchandra Siras | Linguist and author |

| 37 | Living Smile Vidya | Actor, artist, writer, and theater activist |

| 38 | Kalki Subramaniam | Trans activist, actor, artist, writer and founder of Sahodari Foundation |

| 39 | Manil Suri | Indian-American mathematician and writer |

| 40 | S. Swapna | First transwoman to clear Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission exam and first transgender I.A.S aspirant. |

| 41 | Laxmi Narayan Tripathi | Trans activist |

| 42 | Ruth Vanita | Writer and academician |

| 43 | Abhinav Vats | Equal rights activist and India's first openly gay actor; featured in a music video from Euphoria in 1996 in a first ever gay character shown on Indian media |

| 44 | Rose Venkatesan | First trans TV host in India |

| 45 | Riyad Vinci Wadia | Film maker |

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws concerning gender identity | |

| Same-sex marriage | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples (e.g. unregistered cohabitation, life partnership) | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| LGBT people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Third gender option | |

| Access to IVF for lesbian couples | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood |

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Mahapatra, Dhananjay; Choudhary, Amit Anand (7 September 2018). "SC decriminalises Section 377, calls 2013 ruling 'arbitrary and retrograde'". The Times of India.

- 1 2 Singh, Aarti Tikoo (7 September 2018). "Section 377: Pride not extended to J&K". The Times of India.

- 1 2 "In a first, Gurgaon court recognizes lesbian marriage - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- 1 2 Abraham, Rohan (30 November 2017). "All you need to know about the Transgender Persons Bill, 2016". The Hindu.

- 1 2 3 Hundreds of gay rights activists join pride march in Delhi

- ↑ "India: Prosecute Rampant 'Honor' Killings". Human Rights Watch. 18 July 2010.

- ↑ Patel, Rashmi (27 August 2016). "Being LGBT in India: Some home truths". Livemint.com.

- ↑ Jones, Sophia (29 July 2011). "Lesbian newlyweds flee honor killing threats in India". Foreign Policy.

- ↑ Pandey, Vikas (6 September 2018). "What it means to be gay in rural India". BBC News.

- 1 2 3 "India decriminalises gay sex in landmark verdict". Al Jazeera. 6 September 2018.

- ↑ "'Xavier was aware of the brutality of the Inquisition'". Deccan Herald. Deccan Herald. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Sharma, Jai. "The Portuguese Inquisition in Goa: A brief history". Indiafacts.org. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Soyer, Francois (2012). Ambiguous Gender in Early Modern Spain and Portugal: Inquisitors, Doctors and the Transgression of Gender Norms. p. 45. ISBN 9789004225299. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Kugle, Scott A (1 Sep 2011). Sufis and Saints' Bodies: Mysticism, Corporeality, and Sacred Power in Islam. Chapter 4 - Note 62-63: Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 309. ISBN 9780807872772. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ↑ A digest of the Moohummudan law pp. 1-3 with footnotes, Neil Baillie, Smith Elder, London

- ↑ How did the Mughals view homosexuality

- ↑ Khalid, Haroon (17 June 2016). "From Bulleh Shah and Shah Hussain to Amir Khusro, same-sex references abound in Islamic poetry". Scroll.in. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ Sarmad Kashani Tomb in Jami Masjid, New Delhi, India

- ↑ V. N. Datta, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and Sarman,

Walderman Hansen doubts whether sensual passions played any part in their love [sic]; puri doubts about their homosexual relationship

- ↑ Of Genizahs, Sufi Jewish Saints, and Forgotten Corners of History

- 1 2 3 4 Suresh, Mayur (6 September 2018). "This is the start of a new era for India's LGBT communities | Mayur Suresh". The Guardian.

- ↑ "India: The Indian Penal Code". www.wipo.int. World Intellectual Property Organization.

- ↑ Kusum Ingots v. Union of India, (2004) 6 SCC 254: "An order passed on a writ petition questioning the constitutionality of a Parliamentary Act, whether interim or final, keeping in view the provisions contained in Clause (2) of Article 226 of the Constitution of India, will have effect throughout the territory of India subject of course to the applicability of the Act."

- ↑ Pervez Iqbal Siddiqui (28 December 2010). "Crackdown on gay party in Saharanpur, 13 held". The Times of India. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ Mahapatra, Dhananjay (23 February 2012). "Centre opposes decriminalisation of homosexuality in SC". Economic Times. Times Internet. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ↑ "Supreme Court pulls up Centre for flip-flop on homosexuality". The Indian Express. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ↑ "Supreme Court sets aside Delhi High Court judgment in Naz Foundation; Declares S.377 to be constitutional".

- ↑ Nelson, Dean (11 December 2013). "India's top court upholds law criminalising gay sex". London: The Telegraph. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ "Supreme Court makes gay sex punishable offence, again; Twitter war breaks out between those for and against the verdict". DNA India. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Mahapatra, Dhananjay (12 December 2013). "Supreme Court makes homosexuality a crime again". The Times Of India.

- ↑ Full text of 2013 decision

- ↑ IANS (2013-12-11). "Apex court ruling disappointing: rights body". Business Standard India. Retrieved 2017-09-14.

- ↑ Harmit Shah Singh (11 December 2013). "India's Supreme Court declares homosexual sex illegal". CNN.

- ↑ "Naz Foundation to file review petition against SC order on section 377".

- ↑ "Supreme Court refuses overruling its Verdict on Section 377 and Homosexuality". IANS. Biharprabha News. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ↑ J Venkatesan (11 December 2013). "Supreme Court sets aside Delhi HC verdict decriminalising gay sex". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 2013-12-12.

- ↑ "India parliament blocks MP's bill to decriminalize gay sex". Rappler.

- ↑ ABC News. "ABC News". ABC News.

- ↑ India’s Supreme Court Upholds Right to Privacy Human Rights Watch

- ↑ "India's supreme court could be about to decriminalise gay sex in major victory for LGBT rights". independent.co.uk. 8 January 2018.

- ↑ "Six New Petitioners In SC Seeking Scrapping Of Section 377IPC: Hearing On Tuesday". Live Law. 27 April 2018.

- ↑ SC Seeks Govt’s Reply on IITians’ Petition Scrapping Homosexuality

- 1 2 "India on brink of biggest gay rights victory as Supreme Court prepares to rule on gay sex ban". Independent.co.uk. 14 July 2018.

- ↑ Dhruv, Rushabh (5 July 2018). "Just In: Supreme Court to start hearing section 377 case from July 10". In.com.

- ↑ "SC to hear petition against Section 377 next week". www.aninews.in. Asian News International. 6 July 2018.

- ↑ "Section 377: SC reserves order, verdict on constitutional validity likely before October". Paperdabba. 17 July 2018.

- ↑ "Section 377 verdict: Here are the highlights". The Indian Express. 6 September 2018.

- ↑ "India court legalises gay sex in landmark ruling". BBC News. 6 September 2018.

- ↑ Misra, Dipak. "Navtej Singh Johar and Ors. vs Union Of India Ministry Of Law and Justice" (PDF). The Hindu. p. 160. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ↑ "India's top court decriminalizes gay sex in landmark ruling". CNN. 6 September 2018.

- ↑ "Supreme Court decriminalises Section 377: All you need to know". The Times of India. 6 September 2018.

- ↑ "Indian supreme court decriminalises homosexuality". The Guardian. 6 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Das, Shaswati (7 September 2018). "Historic verdict holds hope for same-sex marriages, adoption". Livemint.com.

- ↑ "High Court's 1995 ruling offers hope to Jammu and Kashmir's LGBT community". The Economic Times. 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "SC decriminalises gay sex, but J&K LGBTs will have to wait longer". Times of India. 8 September 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ↑ "Lesbian couple's parents accept their relationship - The Times of India". The Times Of India. 17 August 2011.

- ↑ Nelson, Dean (26 July 2011). "India's first married lesbian couple given 24-hour protection". The Telegraph.

- ↑ Chishti, Seema (18 October 2017). "Drafting change: What the new 'progressive' intervention in Uniform Civil Code debate entails". The Indian Express.

- ↑ "A new UCC for a new India? Progressive draft UCC allows for same sex marriages - Catchnews". Catchnews. Retrieved 2017-10-12.

- ↑ "Article 15 in The Constitution Of India 1949". indiankanoon.org.

- ↑ Dacho Furtad, Konkani-English dictionary. Asian Educational Services, 1999

- ↑ Sinha, Chandrani (2 March 2017). "Manipur Elections 2017: Why is the transgender community of the state backing Irom Sharmila". InUth.

- ↑ Grierson, George Abraham (1932). "A dictionary of the Kashmiri language". Digital Dictionaries of South Asia.

- ↑ Bronson, Miles (1867). A dictionary in Assamese and English. Sibsagor, American Baptist mission press. p. 311.

- ↑ A Santali-English dictionary (in Santali). Santal Mission Press. 1899. p. 86.

- ↑ Shackle, Samira. "Politicians of the third gender: the "shemale" candidates of Pakistan". New Statesman. Retrieved 2013-05-11.

- ↑ "Crystallising Queer Politics-The Naz Foundation Case and Its Implications For India's Transgender Communities" (PDF). NUJS Law Review. 2009.

- ↑ "Supreme Court's Third Gender Status to Transgenders is a landmark". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ Transgender rights in India

- 1 2 Mallick, Lelin (4 November 2017). "State's first transgender passport". The Telegraph.

- ↑ "Transgenders protest demanding name change in certificates - The Times of India". The Times Of India.

- ↑ "Transgenders stage protest at collectorate - The Times of India". The Times Of India. 8 October 2013.

- ↑ "Transgender Clears TNPSC Group IV Exam". The New Indian Express.

- ↑ "Rajya Sabha passes historic private bill to promote transgender rights". The Indian Express. 25 April 2015.

- ↑ "Bills on transgenders, disabled in monsoon session: Gehlot".

- ↑ "Centre's Transgender Bill ridiculous, laments activist Akkai Padmashali". www.deccanchronicle.com/. 2017-11-21. Retrieved 2018-04-25.

- ↑ Devasia, TK. "Why Kerala's free sex-change surgeries will offer a new lifeline for the transgender community". Scroll.in. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ↑ "How Kerala left the country behind on transgender rights". dna. Retrieved 2016-03-19.

- ↑ Dash, Jatindra (2 June 2016). "Odisha becomes first state to give welfare to transgender community". Reuters.

- ↑ Sharma, Kuheena (6 April 2017). "Sanitation ministry allows transgender people use public toilets, wants them recognised as equal citizens". India Today. New Delhi. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ↑ "Transgender policy cleared by Karnataka cabinet". The Indian Express. Press Trust of India. 27 October 2017.

- ↑ CM Naidu announces pension scheme for state's transgenders

- ↑ Apparasu, Srinivasa Rao (17 December 2017). "Transgenders to get pension, ration and more in Andhra; govt clears welfare policy". Hindustan Times.

- ↑ Naqash, Rayan (4 February 2018). "For the first time, Kashmir government recognises needs of transgender community. But is it enough?". Scroll.in.

- ↑ Jammu and Kashmir: Transgender community welcomes steps taken by Mehbooba Mufti government

- ↑ Writing'a'Life'Between'Gender'Lines Conversations'with'A.'Revathi'about'Her'Autobiography' The Truth About Me: A Hijra Life Story

- ↑ Umair, S. M. (29 September 2010). "Hope floats". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- ↑ Winter, Gopi Shankar (2014). Maraikkappatta Pakkangal: மறைக்கப்பட்ட பக்கங்கள். Srishti Madurai. ISBN 9781500380939. OCLC 703235508.

- ↑ Achanta, Pushpa (9 October 2012). "My life, my way". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- ↑ "Doraiswamy to Revathi: A Tamil writer-activist's alternative journey". Deccan Herald.

- ↑ Iyer, Malathy (7 February 2014). "Homosexuality is not a disease, psychiatrists say". The Times of India.

- ↑ Singh, Amrita (1 June 2016). "From Shock Treatment To Yoga, Conversion Therapy Is A Disturbing Reality Around The World". HuffPost India.

- ↑ Power, Shannon (8 June 2018). "India's biggest psychiatric body declares homosexuality is not an illness". Gay Star News.

- ↑ "One Who Fights For an Other". The New Indian Express.

- ↑ Sawant, Anagha (22 July 2016). "Now, a dating platform for LGBT community". Daily News and Analysis.

- ↑ "Same-sex attraction is OK, boys can cry, girl's no means no". The Indian Express. 21 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "Homosexual attraction is OK; 'NO' means no: Health Ministry rises above Indian stereotypes". The Financial Express. 21 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ Menon, Priya (2 June 2018). "A decade of Pride in Chennai". The Times of India.

- ↑ "A walk to remember for the LGBT community - Times of India". The Times of India. 29 October 2017.

- ↑ "As India awaits a historic gay rights ruling, a city holds its first pride march". The Washington Post. 5 September 2018.

- ↑ India – IDAHOTB 2018 Country Page, Erasing 76 Crimes

- ↑ "Accept history and move on". The New Indian Express.

- ↑ "Eunuch MP takes seat". BBC News. 6 March 2000.

- ↑ "Transgender activist Kalki to seek DMK ticket".

- ↑ Jaisankar, C.; Raghunathan, A. V. "Transgender Kalki in poll race". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- ↑ Alter, Charlotte (6 January 2015). "India's First Openly Transgender Mayor Elected". Time.

- ↑ "India's First Openly Transgender Mayor in Her Own Words". The Wall Street Journal. 7 January 2015.

- ↑ "First transgender mayor elected in central India: media". Reuters. 5 January 2015.

- ↑ "Transgender woman is elected district mayor in Indian state of Chhattisgarh". the Guardian.

- ↑ IANS (9 June 2015). "India's first transgender college principal starts work".

- ↑ Ravishankar, Sandhya (10 June 2015). "The First Transgender Principal". Swarajya.

- ↑ "With a little help from Madras HC, Tamil Nadu gets its first transgender police officer". The Indian Express. 7 November 2015.

- ↑ "Lok Adalat makes history, appointed two transgenders as panelist". The Times of India. 12 February 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ↑ "India's first transgender judge Joyita Mondal wants jobs for her community". The New Indian Express.

- ↑ "Assam gets its first transgender judge". The Economic Times. Asian News International. 15 July 2018.

- ↑ Nanda, Serena. Neither Man Nor Woman: The hijras of India, p. xx. Canada: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1999

- ↑ "Read Why Gopi Shankar Calls Attention Of Arundhati Roy To Intersex Community". Indian Women Blog.Org. Retrieved 2018-02-03.

- ↑ "Arundhati Roy's New Book Can Undo Decades Of Work Done By Intersex Activists". Youth Ki Awaaz. Retrieved 2018-02-03.

- ↑ Warne, Garry L.; Raza, Jamal (September 2008). "Disorders of sex development (DSDs), their presentation and management in different cultures". Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 9 (3): 227–236. doi:10.1007/s11154-008-9084-2. ISSN 1389-9155. PMID 18633712.

- ↑ Rajendran, R; Hariharan, S (1995). "Profile of Intersex Children in South India". Indian Pediatrics. 32.

- ↑ Sharma, Radha (February 5, 2014). "Parents prefer male child in intersex operations in Gujarat". Times of India.

- ↑ Gupta, Devendra; Sharma, Shilpa (2012). "Male genitoplasty for 46 XX congenital adrenal hyperplasia patients presenting late and reared as males". Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 16 (6): 935. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.102994. ISSN 2230-8210.

- ↑ Karthikeyan, Ragamalika (February 3, 2017). "Activists say surgical 'correction' of intersex babies at birth wrong, govt doesn't listen". The News Minute.

- ↑ Kalra, Sanjay; Kulshreshtha, Bindu; Unnikrishnan, Ambika Gopalakrishnan (2012). "We care for intersex: For Pinky, for Santhi, and for Anamika". Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 16 (6): 873. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.102980. ISSN 2230-8210.

- ↑ "Indian silver medalist female runner at Asian Games fails gender test". International Herald Tribune. 18 December 2006.

- ↑ "Indian runner fails gender test, loses medal". Sports.espn.go.com. 2006-12-18. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- ↑ "Shanti fails Doha gender test". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. 18 December 2006.

- ↑ "Medical experts doubt Pinki Pramanik can rape". Times of India. 14 November 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ Court of Arbitration for Sport (July 2015). "CAS 2014/A/3759 Dutee Chand v. Athletics Federation of India (AFI) & The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF)" (PDF). Court of Arbitration for Sport.

- ↑ Genel M; Simpson J; de la Chapelle A (August 4, 2016). "The olympic games and athletic sex assignment". JAMA. 316: 1359. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.11850. ISSN 0098-7484.

- 1 2 "ILGA/RIWI Global Attitudes Survey on LGBTI People" (PDF). www.ilga.org. International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 31 December 2016.

- ↑ "Young people and free speech". The Economist. 15 February 2017.

- ↑ "ILGA-RIWI Global attitudes survey". igla.org. The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. October 2017.

- ↑ "Intersex person to contest from Madurai North". 30 April 2016 – via The Hindu.

- ↑ "3rd gender gets a new champion in Tamil Nadu poll ring - Times of India".

- ↑ "Intersex candidate alleges harassment - Times of India".

- ↑ "This intersex person is contesting TN polls, 'ze' wants to change your mind on sexual minorities". 24 April 2016.

- ↑ Dutta, Amrita (7 September 2018). "Indian Army is worried now that men can legally have sex with other men". The Print.

- ↑ Power, Shannon (20 July 2017). "No LGBTI person can donate blood in India". GayStarNews.