Bengali renaissance

| Renaissance |

|---|

"The School of Athens", Raphael, 1509–1511 |

| Topics |

| Regions |

| Criticism |

| Part of a series on |

| Bengalis |

|---|

|

|

Bengali homeland |

|

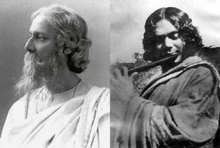

The Bengali renaissance or simply Bengal renaissance, (Bengali: বাংলার নবজাগরণ; Bānglār nabajāgaraṇ) was a cultural, social, intellectual and artistic movement in Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent during the period of the British Indian Empire, from the nineteenth century to the early twentieth century dominated by Bengali Hindus. The Bengal renaissance can be said to have started with Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1772–1833) and ended with Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), although there have been many stalwarts, such as Satyajit Ray (1921-1992), thereafter embodying particular aspects of the unique intellectual and creative output.[1] Nineteenth-century Bengal was a unique blend of religious and social reformers, scholars, literary giants, journalists, patriotic orators and scientists, all merging to form the image of a renaissance, and marked the transition from the 'medieval' to the 'modern'.[2]

Background

During this period, Bengal witnessed an intellectual awakening that is in some way similar to the Renaissance in Europe during the 16th century, although Europeans of that age were not confronted with the challenge and influence of alien colonialism. This movement questioned existing orthodoxies, particularly with respect to women, marriage, the dowry system, the caste system, and religion. One of the earliest social movements that emerged during this time was the Young Bengal movement, that espoused rationalism and atheism as the common denominators of civil conduct among upper caste educated Hindus.

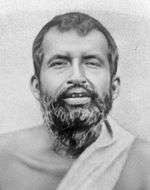

The parallel socio-religious movement, the Brahmo Samaj, developed during this time period and counted many of the leaders of the Bengal Renaissance among its followers.[3] In the earlier years the Brahmo Samaj, like the rest of society, could not however, conceptualize, in that feudal-colonial era, a free India as it was influenced by the European Enlightenment (and its bearers in India, the British Raj) although it traced its intellectual roots to the Upanishads. Their version of Hinduism, or rather Universal Religion (similar to that of Ramakrishna), although devoid of practices like sati and polygamy that had crept into the social aspects of Hindu life, was ultimately a rigid impersonal monotheistic faith, which actually was quite distinct from the pluralistic and multifaceted nature of the way the Hindu religion was practiced. Future leaders like Keshub Chunder Sen were as much devotees of Christ, as they were of Brahma, Krishna or the Buddha. It has been argued by some scholars that the Brahmo Samaj movement never gained the support of the masses and remained restricted to the elite, although Hindu society has accepted most of the social reform programmes of the Brahmo Samaj. It must also be acknowledged that many of the later Brahmos were also leaders of the freedom movement.

The renaissance period after the Indian Rebellion of 1857 saw a magnificent outburst of Bengali literature. While Ram Mohan Roy and Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar were the pioneers, others like Bankim Chandra Chatterjee widened it and built upon it.[4] The first significant nationalist detour to the Bengal Renaissance was given by the writings of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee. Later writers of the period who introduced broad discussion of social problems and more colloquial forms of Bengali into mainstream literature included Saratchandra Chatterjee.

The Tagore family, including Rabindranath Tagore, were leaders of this period and had a particular interest in educational reform.[5] Their contribution to the Bengal Renaissance was multi-faceted. Tagore's 1901 Bengali novella, Nastanirh was written as a critique of men who professed to follow the ideals of the Renaissance, but failed to do so within their own families. In many ways Rabindranath Tagore's writings (especially poems and songs) can be seen as imbued with the spirit of the Upanishads. His works repeatedly allude to Upanishadic ideas regarding soul, liberation, transmigration and—perhaps most essentially—about a spirit that imbues all creation not unlike the Upanishadic Brahman. Tagore's English translation of a set of poems titled the Gitanjali won him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913. He was the first Asian to win this award (and the first non-European/non-white person of 'colour' to win the Nobel Prize in any category). That was the only example at the time but the contribution of the Tagore family is enormous.[6]

Comparison with European renaissance

The word "renaissance" in European history meant "rebirth" and was used in the context of the revival of the Graeco-Roman learning in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries after the long winter of the dark medieval period. A serious comparison was started by the dramatis personae of the Bengal renaissance like Keshab Chandra Sen, Bipin Chandra Pal and M. N. Roy. For about a century, Bengal's conscious awareness and the changing modern world was more developed and ahead of the rest of India. The role played by Bengal in the modern awakening of India is thus comparable to the position occupied by Italy in the European renaissance. Very much like the Italian Renaissance, it was not a mass movement; but instead restricted to the upper classes.

Though the Bengal Renaissance was the "culmination of the process of emergence of the cultural characteristics of the Bengali people that had started in the age of Hussein Shah, it remained predominantly Hindu and only partially Muslim." There were, nevertheless, examples of Muslim intellectuals such as Syed Ameer Ali, Mosharraf Hussain,[7] Sake Dean Mahomed, Kazi Nazrul Islam, and Roquia Sakhawat Hussain. The Freedom of Intellect Movement sought to challenge religious and social dogma in Bengali Muslim society.

Science and technology

During the Bengal Renaissance science was also advanced by several Bengali scientists such as Satyendra Nath Bose, Anil Kumar Gain, Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, Jagadish Chandra Bose and Meghnad Saha. Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose was a polymath: a physicist, biologist, botanist, archaeologist, and writer of science fiction.[8] He pioneered the investigation of radio and microwave optics, made very significant contributions to plant science, and laid the foundations of experimental science in the Indian subcontinent.[9] He is considered one of the fathers of radio science,[10] and is also considered the father of Bengali science fiction. He was the first from the Indian subcontinent to get a US patent, in 1904. Anil Kumar Gain and Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis were leading mathematicians and statisticians of their time. Gain went on to found Vidyasagar University, while Mahalanobis laid the foundation of the Indian Statistical Institute. Satyendra Nath Bose was a physicist, specializing in mathematical physics. He is best known for his work on quantum mechanics in the early 1920s, providing the foundation for Bose-Einstein statistics and the theory of the Bose-Einstein condensate. He is honoured as the namesake of the boson. Although more than one Nobel Prize was awarded for research related to the concepts of the boson, Bose-Einstein statistics and Bose-Einstein condensate—the latest being the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics, which was given for advancing the theory of Bose-Einstein condensates—Bose himself was never awarded the Nobel Prize.

Arts and literature

According to historian Romesh Chunder Dutt:[11]

The conquest of Bengal by the English was not only a political revolution, but ushered in a greater revolution in thoughts and ideas, in religion and society... From the stories of gods and goddesses, kings and queens, princes and princesses, we have learnt to descend to the humble walks of life, to sympathise with the common citizen or even common peasant … Every revolution is attended with vigour, and the present one is no exception to the rule. Nowhere in the annals of Bengali literature are so many and so bright names found crowded together in the limited space of one century as those of Ram Mohan Roy, Akshay Kumar Dutt, Isvar Chandra Vidyasagar, Michael Madhusudan Dutt, Hem Chandra Banerjee, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee and Dina Bandhu Mitra. Within the three quarters of the present century, prose, blank verse, historical fiction and drama have been introduced for the first time in the Bengali literature...

Religion and spirituality

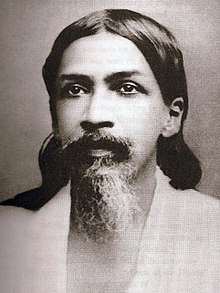

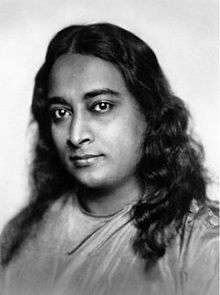

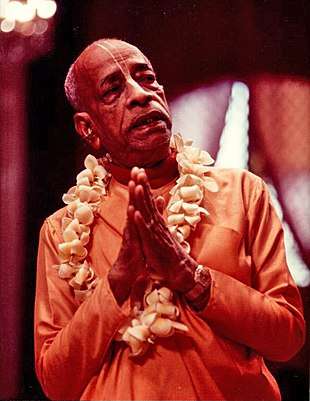

Most notable Bengali religious and spiritual personalities are Atiśa, Tilopa, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, Ramakrishna, Sree Sree Thakur Anukulchandra, Nityananda, Haridasa Thakur, Jiva Goswami, Ramprasad Sen, Lokenath Brahmachari, Swami Vivekananda, Keshub Chandra Sen, Balananda Brahmachari, Vishuddhananda Paramahansa, Sri Aurobindo, Lahiri Mahasaya, Bamakhepa, Yukteswar Giri, Debendranath Tagore, Swami Abhedananda, Bhaktivinoda Thakur, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, Mohanananda Brahmachari, Sitaramdas Omkarnath, Ram Thakur, Lalon, Tibbetibaba, Soham Swami, Nigamananda Paramahansa, Niralamba Swami, Pranavananda, Bijoy Krishna Goswami, Paramahansa Yogananda, Prabhat Ranjan Sarkar, Anukulchandra Chakravarty, Anandamayi Ma, Hariharananda Giri, Anirvan and Sri Chinmoy.

Contributing institutions

- Asiatic Society (est.1784)

- Fort William College (1800)

- Serampore College (1817)

- Calcutta School-Book Society (1817)

- Hindu School (1817)

- Hare School (1818)

- Sanskrit College (1824)

- General Assembly's Institution (1830) (now known as Scottish Church College)

- Calcutta Medical College (1835)

- Mutty Lall Seal's Free School & College (1842)

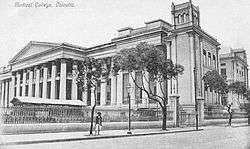

- Hindu College (1817) later Presidency College, Calcutta (1855) now Presidency University (since 2010)

- Bengal Engineering College, Shibpur (1856) now known as Indian Institute of Engineering Science and Technology, Shibpur

- University of Calcutta (1857)

- Vidyasagar College (1872)

- Hindu Mahila Vidyalaya (1873)

- Banga Mahila Vidyalaya (1876)

- Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (1876)

- Bethune College (1879)

- Ripon College (1884) (now known as Surendranath College)

- National Council of Education, Bengal (1906) (now known as Jadavpur University)

- Visva-Bharati University (1921)

- University of Dhaka (1921)

- Maharaja Manindra Chandra College (1941)

- Seth Anandram Jaipuria College (1945)

See also

References

- ↑ History of the Bengali-speaking People by Nitish Sengupta, p 211, UBS Publishers' Distributors Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 81-7476-355-4.

- ↑ Sumit Sarkar, "Calcutta and the Bengal Renaissance", in Calcutta, the Living City ed. Sukanta Chaudhuri, Vol I, p. 95.

- ↑ "Reform and Education: Young Bengal & Derozio", Bengalinet.com

- ↑ History of Bengali-speaking People by Nitish Sengupta, p 253.

- ↑ Kathleen M. O'Connell, "Rabindranath Tagore on Education", infed.org

- ↑ Deb, Chitra, pp 64-65.

- ↑ History of Bengali-speaking People by Nitish Sengupta, p 210, 212-213.

- ↑ A versatile genius Archived 3 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine., Frontline 21 (24), 2004.

- ↑ Chatterjee, Santimay and Chatterjee, Enakshi, Satyendranath Bose, 2002 reprint, p. 5, National Book Trust, ISBN 8123704925

- ↑ Sen, A. K. (1997). "Sir J.C. Bose and radio science". Microwave Symposium Digest. IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium. Denver, CO: IEEE. pp. 557–560. doi:10.1109/MWSYM.1997.602854. ISBN 0-7803-3814-6.

- ↑ Cultural Heritage of Bengal by R. C. Dutt, quoted by Nitish Sengupta, pp 211-212.

Further reading

- Chatterjee, Pranab (2010). A Story of Ambivalent Modernization in Bangladesh and West Bengal: The Rise and Fall of Bengali Elitism in South Asia. Peter Lang. ISBN 9781433108204.

- Dasgupta, Subrata (2005). Twilight of the Bengal renaissance: R.K. Dasgupta & his quest for a world mind. the University of California: Dey's Publishing.

- Dasgupta, Subrata (2009). The Bengal Renaissance. Permanent Black. ISBN 978-8178242798.

- Dasgupta, Subrata (2011). Awakening: The Story of the Bengal Renaissance. Random House India. ISBN 978-8184001839.

- Dhar, Niranjan (1977). Vedanta and the Bengal Renaissance. the University of Michigan: Minerva Associates. ISBN 9780883868379.

- Fraser, Bashabi edited Special Issue on Rabindranath Tagore, Literary Compass, Wiley Publications. Volume 12, Issue 5, May 2015. See Fraser's Introduction pp. 161-72. ISSN 1741-4113.

- Kabir, Abulfazal M. Fazle (2011). The Libraries of Bengal, 1700-1947: The Story of Bengali Renaissance. Promilla & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-8185002071.

- Kopf, David (1969). British Orientalism and the Bengal Renaissance. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520006652.

- Kumar, Raj (2003). Essays on Indian Renaissance. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7141-689-9.

- Marshall, P. J. (2006). Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828 (The New Cambridge History of India). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521028226.

- Mittra, Sitansu Sekhar (2001). Bengal's Renaissance. Academic Publishers. ISBN 9788187504184.

- Pal, Bipin Chandra; Cakrabartī, Jagannātha (1977). Studies in the Bengal renaissance. the University of California: National Council of Education, Bengal.

- Sastri, Sivanath. A History of the Renaissance in Bengal: Ramtanu Lahiri, Brahman and Reformer, London: Swan, Sonnenschein (1903); Kolkata: Renaissance (2002).

- Sastri, Sibnath (2008). Ramtanu Lahiri, Brahman and Reformer: A History of the Renaissance in Bengal. BiblioLife. ISBN 978-0559841064.

- Sen, Amit (2011). Notes on the Bengal Renaissance. Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1179501390.

- Travers, Robert (2007). Ideology and Empire in Eighteenth-Century India: The British in Bengal. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521059688.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bengali renaissance. |

- "The Tagores and Society", Rabindra Bharati Museum Kolkata

- Copf, David (2012). "Bengal Renaissance". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

.jpg)