Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes

The Scheduled Castes[2] (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) are officially designated groups of historically disadvantaged people in India. The terms are recognised in the Constitution of India and the groups are designated in one or other of the categories. For much of the period of British rule in the Indian subcontinent, they were known as the Depressed Classes. The people in scheduled castes are essentially the lowest part of Hindu society.

In modern literature, the Scheduled Castes/Tribes are sometimes referred to as untouchables; in Tamil Nadu they are referred as Adi Dravida; and in other states mostly referred as scheduled castes.[3][4]

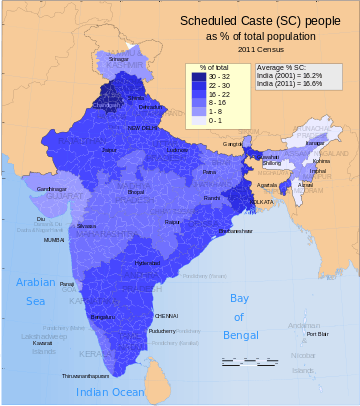

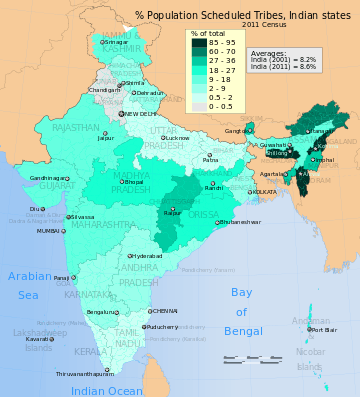

The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes comprise about 16.6% and 8.6%, respectively, of India's population (according to the 2011 census).[5][6] The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950 lists 1,108 castes across 29 states in its First Schedule,[7] and the Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950 lists 744 tribes across 22 states in its First Schedule.[8]

Since the independence of India, the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were given Reservation status, guaranteeing political representation. The Constitution lays down the general principles of positive discrimination for SCs and STs.

History

Historian K.S. Lal wrote that persecution by Muslims, not by high-caste Hindus, was responsible for reducing settled agriculturists and feudal lords to the conditions of nomads and forest-dwellers who went on to be categorized as Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in the modern period.[9]

Since the 1850s these communities were loosely referred to as Depressed Classes, with the Schedule Caste and Scheduled Tribes. The early 20th century saw a flurry of activity in the British authorities assessing the feasibility of responsible self-government for India. The Morley–Minto Reforms Report, Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms Report and the Simon Commission were several initiatives in this context. A highly contested issue in the proposed reforms was the reservation of seats for representation of the Depressed Classes in provincial and central legislatures.

In 1935, Parliament passed the Government of India Act 1935, designed to give Indian provinces greater self-rule and set up a national federal structure. The reservation of seats for the Depressed Classes was incorporated into the act, which came into force in 1937. The Act introduced the term "Scheduled Castes", defining the group as "such castes, parts of groups within castes, which appear to His Majesty in Council to correspond to the classes of persons formerly known as the 'Depressed Classes', as His Majesty in Council may prefer".[10] This discretionary definition was clarified in The Government of India (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1936, which contained a list (or Schedule) of castes throughout the British-administered provinces.

After independence the Constituent Assembly continued the prevailing definition of Scheduled Castes and Tribes, giving (via articles 341 and 342) the president of India and governors of the states a mandate to compile a full listing of castes and tribes (with the power to edit it later, as required). The complete list of castes and tribes was made via two orders: The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950[11] and The Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950,[12] respectively. Furthermore, independent India's quest for inclusivity was incident through the appointment of B. R. Ambedkar as the chair of the drafting committee for the Constitution. Ambedkar was a scheduled caste constitutional lawyer, a member of the low regarded Untouchables.[13]

Steps taken by the government to improve the situation of SC and ST

The Constitution provides a three-pronged strategy[14] to improve the situation of SCs and STs:

- Protective arrangements: Such measures as are required to enforce equality, to provide punitive measures for transgressions, to eliminate established practices that perpetuate inequities, etc. A number of laws were enacted to implement the provisions in the Constitution. Examples of such laws include The Untouchability Practices Act, 1955, Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, The Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, 1993, etc. Despite legislation, social discrimination and atrocities against the backward castes continued to persist.[15]

- Affirmative action: Provide positive treatment in allotment of jobs and access to higher education as a means to accelerate the integration of the SCs and STs with mainstream society. Affirmative action is popularly known as reservation. Article 16 of the Constitution states "nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any provisions for the reservation of appointments or posts in favor of any backward class of citizens, which, in the opinion of the state, is not adequately represented in the services under the State". The Supreme Court upheld the legality of affirmative action and the Mandal Commission (a report that recommended that affirmative action not only apply to the Untouchables, but the other backward castes as well). However, the reservations from affirmative action were only allotted in the public sector, not the private.[16]

- Development: Provide resources and benefits to bridge the socioeconomic gap between the SCs and STs and other communities. Major part played by the Hidayatullah National Law University. Legislation to improve the socioeconomic situation of SCs and STs because twenty-seven percent of SC and thirty-seven percent of ST households lived below the poverty line, compared to the mere eleven percent among other households. Additionally, the backward castes were poorer than other groups in Indian society, and they suffered from higher morbidity and mortality rates.[17]

National commissions

To effectively implement the safeguards built into the Constitution and other legislation, the Constitution under Articles 338 and 338A provides for two statutory commissions: the National Commission for Scheduled Castes,[18] and the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes.[19] The chairpersons of both commissions sit ex officio on the National Human Rights Commission.

Constitutional history

In the original Constitution, Article 338 provided for a special officer (the Commissioner for SCs and STs) responsible for monitoring the implementation of constitutional and legislative safeguards for SCs and STs and reporting to the president. Seventeen regional offices of the Commissioner were established throughout the country.

There was an initiative to replace the Commissioner with a committee in the 48th Amendment to the Constitution, changing Article 338. While the amendment was being debated, the Ministry of Welfare established the first committee for SCs and STs (with the functions of the Commissioner) in August 1978. These functions were modified in September 1987 to include advising the government on broad policy issues and the development levels of SCs and STs. Now it is included in Article 342.

In 1990, Article 338 was amended for the National Commission for SCs and STs with the Constitution (Sixty fifth Amendment) Bill, 1990.[20] The first commission under the 65th Amendment was constituted in March 1992, replacing the Commissioner for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and the commission established by the Ministry of Welfare's Resolution of 1989. In 2003, the Constitution was again amended to divide the National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes into two commissions: the National Commission for Scheduled Castes and the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes. Due to the spread of Christianity and Islam among schedule caste/Tribe community converted are not protected as castes under Indian Reservation policy. Hence, these societies usually forge their community certificate as Hindus and practice Christianity or Islam afraid for their loss of reservation.[21]

Scheduled Castes Sub-Plan

The Scheduled Castes Sub-Plan (SCSP) of 1979 mandated a planning process for the social, economic and educational development of Scheduled Castes and improvement in their working and living conditions. It was an umbrella strategy, ensuring the flow of targeted financial and physical benefits from the general sector of development to the Scheduled Castes.[22] It entailed a targeted flow of funds and associated benefits from the annual plan of states and Union Territories (UTs) in at least a proportion to the national SC population. Twenty-seven states and UTs with sizable SC populations are implementing the plan. Although the Scheduled Castes population according to the 2001 Census was 16.66 crores (16.23% of the total population), the allocations made through SCSP have been lower than the proportional population.[23] A strange factor has emerged of extremely lowered fertility of scheduled castes in Kerala, due to land reform, migrating (Kerala Gulf diaspora) and democratization of education.[24]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Census of India 2011, Primary Census Abstract

- ↑ "Scheduled Caste Welfare – List of Scheduled Castes". Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ↑ Kumar (1992). The affirmative action debate in India, Asian Survey, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 290–302

- ↑ FACTORS AND CONSTRAINTS FOR ADOPTING NEW AGRICULTURAL "I wish that you would issue instructions to your translation committee that the translation of Scheduled Tribes should be, literally meaning original inhabitants or indigenous peoples). The word Adivisi has grace."

- ↑ "2011 Census Primary Census Abstract" (PDF). Censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ "Half of India's dalit population lives in 4 states". Timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ "Text of the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950, as amended". Lawmin.nic.in. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ "Text of the Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950, as amended". Lawmin.nic.in. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ Lal, Kishori Saran. "Chapter 7 Lower Classes and Unmitigated Exploitation". The Legacy of Muslim Rule in India.

- ↑ "Scheduled Communities: A social Development profile of SC/ST's (Bihar, Jharkhand & W.B)" (PDF). Planningcommission.nic.in. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ "THE CONSTITUTION (SCHEDULED CASTES) ORDER, 1950". lawmin.nic.in.

- ↑ "1. THE CONSTITUTION (SCHEDULED TRIBES)". lawmin.nic.in. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017.

- ↑ Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2012). A Concise History of Modern India. New York: Cambridge. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-107-67218-5.

- ↑ Archived 8 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sengupta, Chandan (2013). Democracy, Development, and Decentralization in India: Continuing Debates. Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 978-1136198489.

- ↑ Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2012). A Concise History of Modern India. New York: Cambridge. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-107-67218-5.

- ↑ Sengupta, Chandan (2013). Democracy, Development and Decentralization in India: Continuing Debates. Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 9781136198489.

- ↑ "National Commission for Schedule Castes". Indiaenvironmentportal.org. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ "THE CONSTITUTION (EIGHTY-NINTH AMENDMENT) ACT, 2003". Indiacode.nic.in. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ "Constitution of India as of 29 July 2008" (PDF). The Constitution Of India. Ministry of Law & Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ↑ "Community status lapses on conversion, rules Madras High Court". Thehindu.com. 24 June 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ "Wayback Machine". Web.archive.org. 26 February 2009. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ↑ Bone, Omprakash S. (2015). Mannewar: A Tribal Community in India. Notion Press. ISBN 978-9352063444.

- ↑ S., Pallikadavath,; C., Wilson, (1 July 2005). "A paradox within a paradox: Scheduled caste fertility in Kerala". Pure.iiasa.ac.at. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

Further reading

- Srivastava, Vinay Kumar; Chaudhury, Sukant K. (2009). "Anthropological Studies of Indian Tribes". In Atal, Yogesh. Sociology and Social Anthropology in India. Indian Council of Social Science Research/Pearson Education India. ISBN 9788131720349.