Economy of India under the British Raj

The Indian economy under the British Raj describes the economy of India during the years of the British Raj, from 1858 to 1947. During this period, the Indian economy essentially remained stagnant, growing at the same rate (1.2%) as the population.[1] India experienced deindustrialization during this period.[2] Compared to the Mughal Era, India during the British colonial era had a lower per-capita income, a large decline in the secondary sector,[3] and lower levels of urbanisation.[4]

Economic impact of British imperialism

The subject of the economic impact of British imperialism on India remains disputable. The issue was raised by British Whig politician Edmund Burke who in 1778 began a seven-year impeachment trial against Warren Hastings and the East India Company on charges including mismanagement of the Indian economy. Contemporary historian Rajat Kanta Ray argues the economy established by the British in the 18th century was a form of plunder and a catastrophe for the traditional economy of Mughal India, depleting food and money stocks and imposing high taxes that helped cause the famine of 1770, which killed a third of the people of Bengal.[5] In contrast, historian Niall Ferguson argues that under British rule, the village economy's total after-tax income rose from 27% to 54% (the sector represented three quarters of the entire population) [6] and that the British had invested £270 million in Indian infrastructure, irrigation and industry by the 1880s (representing one-fifth of entire British investment overseas) and by 1914 that figure had reached £400 million. He also argues that the British increased the area of irrigated land by a factor of eight, contrasting with 5% under the Mughals.[6]

P. J. Marshall argues the British regime did not make any sharp break with the traditional economy and control was largely left in the hands of regional rulers. The economy was sustained by general conditions of prosperity through the latter part of the 18th century, except the frequent famines with high fatality rates. Marshall notes the British raised revenue through local tax administrators and kept the old Mughal rates of taxation. Marshall also contends the British managed this primarily indigenous-controlled economy through cooperation with Indian elites.[7]

Absence of industrialisation

The views of historians and economists

Historians have questioned why India did not undergo industrialisation in the nineteenth century in the way that Britain did. In the seventeenth century, India was a relatively urbanised and commercialised nation with a buoyant export trade, devoted largely to cotton textiles, but also including silk, spices, and rice. India was the world's main producer of cotton textiles and had a substantial export trade to Britain, as well as many other European countries, via the East India Company. Yet as the British cotton industry underwent a technological revolution during the late 18th to early 19th centuries, the Indian industry stagnated and deindustrialized.[2] India also underwent a period of deindustrialization in the latter half of the 18th century as an indirect outcome of the collapse of the Mughal Empire.[8]

Even as late as 1772, Henry Patullo, in the course of his comments on the economic resources of Bengal, could claim confidently that the demand for Indian textiles could never reduce, since no other nation could equal or rival it in quality.[9] However, by the early nineteenth century, the beginning of a long history of decline of textile exports is observed.[10]

A commonly cited legend is that in the early 19th century, the East India Company (EIC), had cut off the hands of hundreds of weavers in Bengal in order to destroy the indigenous weaving industry in favour of British textile imports (some anecdotal accounts say the thumbs of the weavers of Dacca were removed). However this is generally considered to be a myth, originating from William Bolts' 1772 account where he alleges that a number of silk spinners had cut off their own thumbs in protest at poor working conditions.[11][12]

Several historians have suggested that the lack of industrialization was because India was still a largely agricultural nation with low wages levels, arguing that wages were high in Britain so cotton producers had the incentive to invent and purchase expensive new labour-saving technologies, and that wages levels were low in India so producers preferred to increase output by hiring more workers rather than investing in technology.[13] Several economic historians have criticized this argument, such as Prasannan Parthasarathi who pointed to earnings data that show real wages in 18th-century Bengal and Mysore were higher than in Britain. Workers in the textile industry, for example, earned more in Bengal and Mysore than they did in Britain, while agricultural labour in Britain had to work longer hours to earn the same amount as in Mysore.[14][8] According to evidence cited by the economic historians Immanuel Wallerstein, Irfan Habib, Percival Spear, and Ashok Desai, per-capita agricultural output and standards of consumption in 17th-century Mughal India was higher than in 17th-century Europe and early 20th-century British India.[15]

British control of trade, and exports of cheap Manchester cotton are cited as significant factors, though Indian textiles had still maintained a competitive price advantage compared to British textiles until the 19th century.[16] Several historians point to the colonization of India as a major factor in both India's deindustrialization and Britain's Industrial Revolution.[17][18][19] British colonization forced open the large Indian market to British goods, which could be sold in India without any tariffs or duties, compared to local Indian producers who were heavily taxed. In Britain protectionist policies such as bans and high tariffs were implemented to restrict Indian textiles from being sold there, whereas raw cotton was imported from India without tariffs to British factories which manufactured textiles. British economic policies gave them a monopoly over India's large market and raw materials such as cotton.[2][16][20] India served as both a significant supplier of raw goods to British manufacturers and a large captive market for British manufactured goods.[21]

Declining share of world GDP

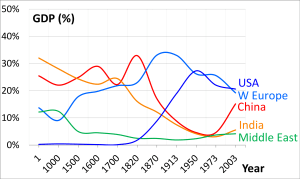

There is no doubt that our grievances against the British Empire had a sound basis. As the painstaking statistical work of the Cambridge historian Angus Maddison has shown, India's share of world income collapsed from 22.6% in 1700, almost equal to Europe's share of 23.3% at that time, to as low as 3.8% in 1952. Indeed, at the beginning of the 20th century, "the brightest jewel in the British Crown" was the poorest country in the world in terms of per capita income.

According to British economist Angus Maddison, India's share of the world economy went from 24.4% in 1700 to 4.2% in 1950. India's GDP (PPP) per capita was stagnant during the Mughal Empire and began to decline prior to the onset of British rule.[24] India's share of global industrial output also declined from 25% in 1750 down to 2% in 1900.[8] At the same time, the United Kingdom's share of the world economy rose from 2.9% in 1700 up to 9% in 1870,[24] and Britain replaced India as the world's largest textile manufacturer in the 19th century.[16] Mughal India also had a higher per-capita income in the late 16th century than British India had in the early 20th century, and the secondary sector contributed a higher percentage to the Mughal economy (18.2%) than it did to the economy of early 20th-century British India (11.2%).[3] In terms of urbanization, Mughal India also had a higher percentage of its population (15%) living in urban centers in 1600 than British India did in the 19th century.[4]

A number of modern economic historians have blamed the colonial rule for the dismal state of India's economy, with investment in Indian industries limited since it was a colony.[25][26] Under British rule, India experienced deindustrialization: the decline of India's native manufacturing industries.[2][16][20] The economic policies of the British Raj caused a severe decline in the handicrafts and handloom sectors, with reduced demand and dipping employment;[27] the yarn output of the handloom industry, for example, declined from 419 million pounds in 1850 down to 240 million pounds in 1900.[8] Due to the colonial policies of the British, the result was a significant transfer of capital from India to England leading to a massive drain of revenue, rather than any systematic effort at modernisation of the domestic economy.[28]

| Year | PPP GDP per Capita of India (as % of UK) |

|---|---|

| 1820 | 31.25 |

| 1870 | 16.72 |

| 1913 | 13.68 |

Agriculture and industry

The Indian economy grew at about 1% per year from 1880 to 1920, and the population also grew at 1%.[1] The result was, on average, no long-term change in income levels. Agriculture was still dominant, with most peasants at the subsistence level. Extensive irrigation systems were built, providing an impetus for growing cash crops for export and for raw materials for Indian industry, especially jute, cotton, sugarcane, coffee and tea.[29] Agricultural income imparted the strongest effect on GDP. Agriculture grew by expanding the land frontier between 1860 and 1914; this became more difficult after 1914.[30]

The entrepreneur Jamsetji Tata (1839–1904) began his industrial career in 1877 with the Central India Spinning, Weaving, and Manufacturing Company in Bombay. While other Indian mills produced cheap coarse yarn (and later cloth) using local short-staple cotton and cheap machinery imported from Britain, Tata did much better by importing expensive longer-stapled cotton from Egypt and buying more complex ring-spindle machinery from the United States to spin finer yarn that could compete with imports from Britain.[31] The effect of industry was a combination of two distinct processes: a robust growth of modern factories and a slow growth in artisanal industry, which achieved higher growth by changing from traditional household-based production to wage-based production.[32]

In the 1890s, Tata launched plans to expand into heavy industry using Indian funding. The Raj did not provide capital, but aware of Britain's declining position against the U.S. and Germany in the steel industry, it wanted steel mills in India so it did promise to purchase any surplus steel Tata could not otherwise sell.[33] The Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO), now headed by his son Dorabji Tata (1859–1932), opened its plant at Jamshedpur in Bihar in 1908. It became the leading iron and steel producer in India, with 120,000 employees in 1945.[34] TISCO became India's proud symbol of technical skill, managerial competence, entrepreneurial flair, and high pay for industrial workers.[35]

Irrigation

The British Raj invested heavily in infrastructure, including canals and irrigation systems in addition to railways, telegraphy, roads and ports.[36][37][38] The Ganges Canal reached 350 miles from Hardwar to Cawnpore, and supplied thousands of miles of distribution canals. By 1900 the Raj had the largest irrigation system in the world. One success story was Assam, a jungle in 1840 that by 1900 had 4,000,000 acres under cultivation, especially in tea plantations. In all, the amount of irrigated land multiplied by a factor of eight. Historian David Gilmour says:

- By the 1870s the peasantry in the districts irrigated by the Ganges Canal were visibly better fed, housed and dressed than before; by the end of the century the new network of canals in the Punjab at producing even more prosperous peasantry there.[39]

Railways

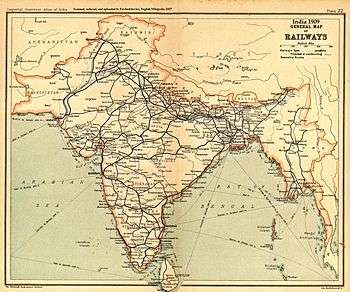

British investors built a modern railway system in the late 19th century—it became the then fourth largest in the world and was renowned for quality of construction and service.[40] The government was supportive, realising its value for military use, as well as its value for economic growth. All the funding and management came from private British companies. The railways at first were privately owned and operated, and run by British administrators, engineers and skilled craftsmen. At first, only the unskilled workers were Indians.[41]

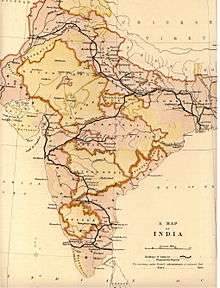

A plan for a rail system in India was first put forward in 1832. The first train in India ran from Red Hills to Chintadripet bridge in Madras in 1837. It was called Red Hill Railway.[42] It was used for freight transport only. A few more short lines were built in 1830s and 1840s but they did not interconnect and were used for freight transport only. The East India Company (and later the colonial government) encouraged new railway companies backed by private investors under a scheme that would provide land and guarantee an annual return of up to five percent during the initial years of operation. The companies were to build and operate the lines under a 99-year lease, with the government having the option to buy them earlier.[42] In 1854 Governor-General Lord Dalhousie formulated a plan to construct a network of trunk lines connecting the principal regions of India. Encouraged by the government guarantees, investment flowed in and a series of new rail companies were established, leading to rapid expansion of the rail system in India.[43]

In 1853 the first passenger train service was inaugurated between Bori Bunder in Bombay and Thane, covering a distance of 34 km (21 mi).[44] The route mileage of this network increased from 1,349 km (838 mi) in 1860 to 25,495 km (15,842 mi) in 1880 – mostly radiating inland from the three major port cities of Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta.[45] Most of the railway construction was done by Indian companies supervised by British engineers. The system was heavily built, in terms of sturdy tracks and strong bridges. Soon several large princely states built their own rail systems and the network spread to almost all the regions in India. [42] By 1900 India had a full range of rail services with diverse ownership and management, operating on broad, metre and narrow gauge networks.[46]

During the First World War, the railways were used to transport troops and grain to the ports of Bombay and Karachi en route to Britain, Mesopotamia, and East Africa. With shipments of equipment and parts from Britain curtailed, maintenance became much more difficult; critical workers entered the army; workshops were converted to making artillery; some locomotives and cars were shipped to the Middle East. The railways could barely keep up with the increased demand.[47] By the end of the war, the railways had deteriorated badly.[48][46] In the Second World War the railway's rolling stock was diverted to the Middle East, and the railway workshops were converted into munitions workshops. This crippled the railways.[49]

Headrick argues that both the Raj lines and the private companies hired only European supervisors, civil engineers, and even operating personnel, such as locomotive engineers. The government's Stores Policy required that bids on railway contracts be made to the India Office in London, shutting out most Indian firms. The railway companies purchased most of their hardware and parts in Britain. There were railway maintenance workshops in India, but they were rarely allowed to manufacture or repair locomotives. TISCO could not obtain orders for rails until the 1920s.[50]

Christensen (1996) looks at of colonial purpose, local needs, capital, service, and private-versus-public interests. He concludes that making the railways a creature of the state hindered success because railway expenses had to go through the same time-consuming and political budgeting process as did all other state expenses. Railway costs could therefore not be tailored to the timely needs of the railways or their passengers.[51]

In 1951, forty-two separate railway systems, including thirty-two lines owned by the former Indian princely states, were amalgamated to form a single unit named Indian Railways. The existing rail systems were abandoned in favor of zones in 1951 and a total of six zones came into being in 1952.[46]

Depression

The worldwide Great Depression of 1929 had little direct impact on India, with only slight impact on the modern secondary sector. The government did little to alleviate distress, and was focused mostly on shipping gold to Britain.[52] The worst consequences involved deflation, which increased the burden of the debt on villagers while lowering the cost of living.[53] In terms of volume of total economic output, there was no decline between 1929 and 1934. Falling prices for jute (and also wheat) hurt larger growers. The worst hit sector was jute, based in Bengal, which was an important element in overseas trade; it had prospered in the 1920s but was hard hit in the 1930s.[54] In terms of employment, there was some decline, while agriculture and small-scale industry exhibited gains.[55] The most successful new industry was sugar, which had meteoric growth in the 1930s.[56][57]

Aftermath

The newly independent but weak Union government's treasury reported annual revenue of £334 million in 1950. In contrast, Nizam Asaf Jah VII of south India was widely reported to have a fortune of almost £668 million then.[58] About one-sixth of the national population were urban by 1950.[59] A US Dollar was exchanged at 4.97 Rupees.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 B. R. Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India, 1860–1970 (1996) p. 5

- 1 2 3 4 James Cypher (2014). The Process of Economic Development. Routledge.

- 1 2 Shireen Moosvi (2015). "The Economy of the Mughal Empire c. 1595: A Statistical Study". Oxford Scholarship Online. Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 Abraham Eraly (2007), The Mughal World: Life in India's Last Golden Age, page 5, Penguin Books

- ↑ Rajat Kanta Ray, "Indian Society and the Establishment of British Supremacy, 1765–1818," in The Oxford History of the British Empire: vol. 2, "The Eighteenth Century" ed. by P. J. Marshall, (1998), pp 508–29

- 1 2 Niall Ferguson (2004). Empire: How Britain Made The Modern World. Penguin Books. p. 216.

- ↑ P.J. Marshall, "The British in Asia: Trade to Dominion, 1700–1765," in The Oxford History of the British Empire: vol. 2, "The Eighteenth Century" ed. by P. J. Marshall, (1998), pp 487–507

- 1 2 3 4 Jeffrey G. Williamson, David Clingingsmith (August 2005). "India's Deindustrialization in the 18th and 19th Centuries" (PDF). Harvard University. Retrieved 2017-05-18.

- ↑ K. N., Chaudhuri (1978). The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company: 1660–1760. Cambridge University Press. p. 237. ISBN 9780521031592.

- ↑ India and the Contemporary World – II (March 2007 ed.). National Council of Educational Research and Training. p. 116. ISBN 8174507078.

- ↑ Wendy Doniger. (2010). The Hindus: An Alternative History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 582.

- ↑ Bolts, William (1772). Considerations on India affairs: particularly respecting the present state of Bengal and its dependencies. J. Almon. p. 194. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ↑ Griffin, Emma. "Why was Britain first? The industrial revolution in global context". Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011), Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850, Cambridge University Press, pp. 38–45, ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0

- ↑ Vivek Suneja (2000). Understanding Business: A Multidimensional Approach to the Market Economy. Psychology Press. p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 Broadberry, Stephen; Gupta, Bishnupriya (2005). "Cotton textiles and the great divergence: Lancashire, India and shifting competitive advantage, 1600–1850" (PDF). International Institute of Social History. Department of Economics, University of Warwick. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ Junie T. Tong (2016), Finance and Society in 21st Century China: Chinese Culture Versus Western Markets, page 151, CRC Press

- ↑ John L. Esposito (2004), The Islamic World: Past and Present 3-Volume Set, page 190, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Ray, Indrajit (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857), Routledge, ISBN 1136825525

- 1 2 Paul Bairoch (1995). Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. University of Chicago Press. p. 89.

- ↑ Henry Yule, A. C. Burnell (2013). Hobson-Jobson: The Definitive Glossary of British India. Oxford University Press. p. 20.

- ↑ Data table in Maddison A (2007), Contours of the World Economy I-2030AD, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199227204

- ↑ "Of Oxford, economics, empire, and freedom". The Hindu. Chennai. 2 October 2005. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- 1 2 Maddison, Angus (2003): Development Centre Studies The World Economy Historical Statistics: Historical Statistics, OECD Publishing, ISBN 9264104143, page 261

- ↑ Booker, M. Keith (1997). Colonial Power, Colonial Texts: India in the Modern British Novel. University of Michigan. pp. 153–154. ISBN 9780472107803.

- ↑ T.R. Jain; V.K. Ohri. Statistics for Economics and indian economic development. VK publications. p. 15. ISBN 9788190986496.

- ↑ Kumar, Dharma (2005). The Cambridge Economic History of India, Volume II : c. 1757–2003. New Delhi: Orient Longman. pp. 538–540. ISBN 978-81-250-2710-2.

- ↑ Kumar, Dharma (2005). The Cambridge Economic History of India, Volume II : c. 1757–2003. New Delhi: Orient Longman. pp. 876–877. ISBN 978-81-250-2710-2.

- ↑ B. H. Tomlinson, "India and the British Empire, 1880–1935," Indian Economic and Social History Review, (Oct 1975), 12#4 pp 337–380

- ↑ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 255. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ↑ F. H. Brown and B. R. Tomlinson, "Tata, Jamshed Nasarwanji (1839–1904)", in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004) accessed 28 Jan 2012 doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36421

- ↑ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 255. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ↑ Vinay Bahl, "The Emergence of Large-Scale Steel Industry in India Under British Colonial Rule, 1880–1907," Indian Economic and Social History Review, (Oct 1994) 31#4 pp 413–460

- ↑ Chikayoshi Nomura, "Selling steel in the 1920s: TISCO in a period of transition," Indian Economic and Social History Review (January/March 2011) 48: pp 83–116, doi:10.1177/001946461004800104

- ↑ Vinay Bahl, Making of the Indian Working Class: A Case of the Tata Iron & Steel Company, 1880–1946 (1995)

- ↑ Neil Charlesworth, British Rule and the Indian Economy, 1800–1914 (1981) pp. 23–37

- ↑ Ian Stone, Canal Irrigation in British India: Perspectives on Technological Change in a Peasant Economy (2002) pp. 278–80

- ↑ for the historiography, see Rohan D’Souza, "Water in British India: the making of a ‘colonial hydrology’." History Compass (2006) 4#4 pp. 621–28. online

- ↑ David Gilmour (2007). The Ruling Caste: Imperial Lives in the Victorian Raj. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 9. ISBN 9780374530808.

- ↑ Ian J. Kerr (2007). Engines of change: the railroads that made India. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-98564-6.

- ↑ I. D. Derbyshire, "Economic Change and the Railways in North India, 1860–1914," Modern Asian Studies, (1987), 21#3 pp. 521–545 in JSTOR

- 1 2 3 R.R. Bhandari (2005). Indian Railways: Glorious 150 years. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 1–19. ISBN 81-230-1254-3.

- ↑ Thorner, Daniel (2005). "The pattern of railway development in India". In Kerr, Ian J. Railways in Modern India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 80–96. ISBN 0-19-567292-5.

- ↑ Babu, T. Stanley (2004). A shining testimony of progress. Indian Railways. Indian Railway Board. p. 101.

- ↑ Hurd, John (2005). "Railways". In Kerr, Ian J. Railways in Modern India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 147–172–96. ISBN 0-19-567292-5.

- 1 2 3 R.R. Bhandari (2005). Indian Railways: Glorious 150 years. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 44–52. ISBN 81-230-1254-3.

- ↑ Daniel R. Headrick, The tentacles of progress: technology transfer in the age of imperialism, 1850–1940, (1988) pp 78–79

- ↑ Awasthi, Aruna (1994). History and development of railways in India. New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications. pp. 181–246.

- ↑ Wainwright, A. Marin (1994). Inheritance of Empire. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-275-94733-0.

- ↑ Daniel R. Headrick, The tentacles of progress: technology transfer in the age of imperialism, 1850–1940, (1988) pp 8–82

- ↑ R. O. Christensen, "The State and Indian Railway Performance, 1870–1920: Part I, Financial Efficiency and Standards of Service," Journal of Transport History (Sept. 1981) 2#2, pp. 1–15

- ↑ K. A. Manikumar, A colonial economy in the Great Depression, Madras (1929–1937) (2003) p 138-9

- ↑ Dietmar Rothermund, An Economic History of India to 1991 (1993) p 95

- ↑ Omkar Goswami, "Agriculture in Slump: The Peasant Economy of East and North Bengal in the 1930s," Indian Economic & Social History Review, July 1984, Vol. 21 Issue 3, p335-364

- ↑ Colin Simmons, "The Great Depression and Indian Industry: Changing Interpretations and Changing Perceptions," Modern Asian Studies, May 1987, Vol. 21 Issue 3, pp 585–623

- ↑ Dietmar Rothermund, An Economic History of India to 1991 (1993) p 111

- ↑ Dietmar Rothermund, India in the Great Depression, 1929–1939 (New Delhi, 1992).

- ↑ "His Fortune on TIME". Time.com. 19 January 1959. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ One-sixth of Indians were urban by 1950

References

- Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (2003), Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy, London and New York: Routledge, 2nd edition. Pp. xiii, 304, ISBN 0-415-30787-2 .

- Oldenburg, Philip (2007), ""India: Movement for Freedom"", Encarta Encyclopedia, archived from the original on 31 October 2009 .

- Stein, Burton (2001), A History of India, New Delhi and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pp. xiv, 432, ISBN 0-19-565446-3

Further reading

- Adams, John; West, Robert Craig (1979), "Money, Prices, and Economic Development in India, 1861–1895", Journal of Economic History, Cambridge University Press, 39 (1): 55–68, doi:10.1017/S0022050700096297, JSTOR 2118910

- Appleyard, Dennis R. (2006), "The Terms of Trade between the United Kingdom and British India, 1858–1947", Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54: 635–654, doi:10.1086/500031

- Bannerjee, Abhijit; Iyer, Lakshmi (2005), "History, Institutions, and Economic Performance: The Legacy of Colonial Land Tenure Systems in India", American Economic Review, American Economic Association, 95 (4): 1190–1213, doi:10.1257/0002828054825574, JSTOR 4132711

- Bayly, C. A. (1985), "State and Economy in India over Seven Hundred Years", The Economic History Review, New Series, Blackwell Publishing, 38 (4): 583–596, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1985.tb00391.x, JSTOR 2597191

- Bayly, C. A. (2008), "Indigenous and Colonial Origins of Comparative Economic Development: The Case of Colonial India and Africa", World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 4474

- Bose, Sumit (1993), Peasant Labour and Colonial Capital: Rural Bengal since 1770 (New Cambridge History of India), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. .

- Broadberry, Stephen; Gupta, Bishnupriya (2007), Lancashire, India and shifting competitive advantage in cotton textiles, 1700–1850: the neglected role of factor prices

- Clingingsmith, David; Williamson, Jeffrey G. (2008), "Deindustrialization in 18th and 19th century India: Mughal decline, climate shocks and British industrial ascent", Explorations in Economic History, 45 (3): 209–234, doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2007.11.002

- Cuenca-Esteban, Javier (2007), "India's contribution to the British balance of payments, 1757–1812", Explorations in Economic History, 44 (1): 154–176, doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2005.10.007

- Collins, William J. (1999), "Labor Mobility, Market Integration, and Wage Convergence in Late 19th Century India", Explorations in Economic History, 36: 246–277, doi:10.1006/exeh.1999.0718

- Farnie, DA (1979), The English Cotton Industry and the World Market, 1815–1896, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Pp. 414, ISBN 0-19-822478-8

- Ferguson, Niall; Schularick, Moritz (2006), "The Empire Effect: The Determinants of Country Risk in the First Age of Globalization, 1880–1913", Journal of Economic History, 66 (2): 283–312, doi:10.1017/S002205070600012X

- Ghose, Ajit Kumar (1982), "Food Supply and Starvation: A Study of Famines with Reference to the Indian Subcontinent", Oxford Economic Papers, New Series, 34 (2): 368–389

- Grada, Oscar O. (1997), "Markets and famines: A simple test with Indian data", Economic Letters, 57: 241–244, doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(97)00228-0

- Guha, R. (1995), A Rule of Property for Bengal: An Essay on the Idea of the Permanent Settlement, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, ISBN 0-521-59692-0

- Habib, Irfan (2007), Indian Economy 1858–1914, Aligarh: Aligarh Historians Society and New Delhi: Tulika Books. Pp. xii, 249., ISBN 81-89487-12-4

- Harnetty, Peter (July 1991), "'Deindustrialization' Revisited: The Handloom Weavers of the Central Provinces of India, c. 1800-1947", Modern Asian Studies, Cambridge University Press, 25 (3): 455–510, doi:10.1017/S0026749X00013901, JSTOR 312614

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III (1907), The Indian Empire, Economic, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxx, 1 map, 552.

- Kumar, Dharma; Raychaudhuri, Tapan; et al., eds. (2005), The Cambridge Economic History of India: c. 1757 – 2003, Cambridge University Press. 2ND ED. Pp. 1078, ISBN 0-521-22802-6

- McAlpin, Michelle B. (1979), "Dearth, Famine, and Risk: The Changing Impact of Crop Failures in Western India, 1870–1920", The Journal of Economic History, 39 (1): 143–157, doi:10.1017/S0022050700096352

- Ray, Rajat Kanta (1995), "Asian Capital in the Age of European Domination: The Rise of the Bazaar, 1800–1914", Modern Asian Studies, 29 (3): 449–554, doi:10.1017/S0026749X00013986, JSTOR 312868

- Roy, Tirthankar (Summer 2002), "Economic History and Modern India: Redefining the Link", The Journal of Economic Perspectives, American Economic Association, 16 (3): 109–130, doi:10.1257/089533002760278749, JSTOR 3216953

- Roy, Tirthankar (2006), The Economic History of India 1857–1947, Second Edition, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Pp. xvi, 385., ISBN 0-19-568430-3

- Roy, Tirthankar (2007), "Globalisation, factor prices, and poverty in colonial India", Australian Economic History Review, 47 (1): 73–94, doi:10.1111/j.1467-8446.2006.00197.x

- Roy, Tirthankar (2008), "Sardars, Jobbers, Kanganies: The Labour Contractor and Indian Economic History", Modern Asian Studies, 42: 971–998, doi:10.1017/S0026749X07003071

- Sen, A. K. (1982), Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Pp. ix, 257, ISBN 0-19-828463-2

- Studer, Roman (2008), "India and the Great Divergence: Assessing the Efficiency of Grain Markets in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century India", Journal of Economic History, 68: 393–437, doi:10.1017/S0022050708000351

- Tirthankar, Roy. "Financing the Raj: the City of London and colonial India 1858–1940." Business History 56#6 (2014): 1024-1026.

- Tomlinson, B. R. (1993), The Economy of Modern India, 1860–1970 (The New Cambridge History of India, III.3), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press., ISBN 0-521-58939-8

- Tomlinson, B. R. (2001), "Economics and Empire: The Periphery and the Imperial Economy", in Porter, Andrew, Oxford History of the British Empire: The Nineteenth Century, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 53–74, ISBN 0-19-924678-5

- Travers, T. R. (2004), "'The Real Value of the Lands': The Nawabs, the British and the Land Tax in Eighteenth-Century Bengal", Modern Asian Studies, 38 (3): 517–558, doi:10.1017/S0026749X03001148

- Wolpert, Stanley, ed. Encyclopedia of India (4 vol. 2005) comprehensive coverage by scholars

- Jadunath Sarkar, Economics of British India (1965)