Nepal

| Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल (Nepali) Saṅghīya Lokatāntrik Gaṇatantra Nepāl | |

|---|---|

|

Motto: जननी जन्मभूमिश्च स्वर्गादपि गरीयसी (Sanskrit) Mother and Motherland are Greater than Heaven (English) | |

.svg.png) | |

_-_NPL_-_UNOCHA.svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city |

Kathmandu 28°10′N 84°15′E / 28.167°N 84.250°ECoordinates: 28°10′N 84°15′E / 28.167°N 84.250°E |

| Official languages |

Nepali (at national level; in 6 provinces) Maithili and Bhojpuri (at national level; in 1 federal state) English (de facto lingua franca; legal documents) |

| Recognised national languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2011[2] ) | |

| Religion |

81.3% Hinduism 9% Buddhism 4.4% Islam 3% Kirant 1.4% Christianity 0.4% Animism 0.5% Irreligion[3][4] |

| Demonym | Nepalese |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic |

| Bidhya Devi Bhandari | |

| Nanda Kishor Pun | |

| Khadga Prasad Oli | |

| Om Prakash Mishra | |

| Ganesh Prasad Timilsina | |

| Krishna Bahadur Mahara[5] | |

| Legislature | Federal Parliament |

| National Assembly | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Formation | |

| 25 September 1768[6] | |

| 18 May 2006[7] | |

| 29 May 2008 | |

| 20 September 2015 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 147,181 km2 (56,827 sq mi) (93rd) |

• Water (%) | 2.8 |

| Population | |

• 2016 estimate | 28,982,771[8] (48th) |

• 2011 census | 26,494,504[2] |

• Density | 180/km2 (466.2/sq mi) (62nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $84 billion[9] |

• Per capita | $2,842[9] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $27 billion[9] |

• Per capita | $919[9] |

| Gini (2010) |

medium |

| HDI (2017) |

medium · 149th |

| Currency | Nepalese rupee (NPR) |

| Time zone | UTC+05:45 (Nepal Standard Time) |

| DST not observed | |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +977 |

| ISO 3166 code | NP |

| Internet TLD | |

Nepal (/nəˈpɔːl/ (![]()

![]()

The name "Nepal" is first recorded in texts from the Vedic Age, the era in which Hinduism was founded, the predominant religion of the country. In the middle of the first millennium BCE, Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, was born in Lumbini in southern Nepal. Parts of northern Nepal were intertwined with the culture of Tibet. The centrally located Kathmandu Valley was the seat of the prosperous Newar confederacy known as Nepal Mandala. The Himalayan branch of the ancient Silk Road was dominated by the valley's traders. The cosmopolitan region developed distinct traditional art and architecture. By the 18th century, the Gorkha Kingdom achieved the unification of Nepal. The Shah dynasty established the Kingdom of Nepal and later formed an alliance with the British Empire, under its Rana dynasty of premiers. The country was never colonised but served as a buffer state between Imperial China and colonial India.[16][17][18] Parliamentary democracy was introduced in 1951, but was twice suspended by Nepalese monarchs, in 1960 and 2005. The Nepalese Civil War in the 1990s and early 2000s resulted in the proclamation of a secular republic in 2008, ending the world's last Hindu monarchy.[19]

The Constitution of Nepal, adopted in 2015, establishes Nepal as a federal secular parliamentary republic divided into seven provinces. Nepal was admitted to the United Nations in 1955, and friendship treaties were signed with India in 1950 and the People's Republic of China in 1960.[20][21] Nepal hosts the permanent secretariat of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), of which it is a founding member. Nepal is also a member of the Non Aligned Movement and the Bay of Bengal Initiative. The military of Nepal is the fifth largest in South Asia; it is notable for its Gurkha history, particularly during the world wars, and has been a significant contributor to United Nations peacekeeping operations.

Etymology

Local legends have it that a Hindu sage named "Ne" established himself in the valley of Kathmandu in prehistoric times, and that the word "Nepal" came into existence as the place was protected ("pala" in Pali) by the sage "Nemi". It is mentioned in Vedic texts that this region was called Nepal centuries ago. According to the Skanda Purana, a rishi called "Nemi" used to live in the Himalayas.[22] In the Pashupati Purana, he is mentioned as a saint and a protector.[23] He is said to have practised meditation at the Bagmati and Kesavati rivers[24] and to have taught there.[25]

The name of the country is also identical in origin to the name of the Newar people. The terms "Nepāl", "Newār", "Newāl" and "Nepār" are phonetically different forms of the same word, and instances of the various forms appear in texts in different times in history. Nepal is the learned Sanskrit form and Newar is the colloquial Prakrit form.[26] A Sanskrit inscription dated 512 CE found in Tistung, a valley to the west of Kathmandu, contains the phrase "greetings to the Nepals" indicating that the term "Nepal" was used to refer to both the country and the people.[27][28]

It has been suggested that "Nepal" may be a Sanskritization of "Newar", or "Newar" may be a later form of "Nepal".[29] According to another explanation, the words "Newar" and "Newari" are vulgarisms arising from the mutation of P to V, and L to R.[30]

History

.jpg)

Ancient

Neolithic tools found in the Kathmandu Valley indicate that people have been living in the Himalayan region for at least eleven thousand years.[31]

Nepal is first mentioned in the late Vedic Atharvaveda Pariśiṣṭa as a place exporting blankets, and in the post-Vedic Atharvashirsha Upanishad.[32] In Samudragupta's Allahabad Pillar it is mentioned as a border country. The Skanda Purana has a separate chapter known as "Nepal Mahatmya", which explains in more detail about the beauty and power of Nepal.[33] Nepal is also mentioned in Hindu texts such as the Narayana Puja.[32]

Legends and ancient texts that mention the region now known as Nepal reach back to the 30th century BC.[34] The Gopal Bansa were likely one of the earliest inhabitants of Kathmandu valley. The earliest rulers of Nepal were the Kiratas (Kirata Kingdom), peoples often mentioned in Hindu texts, who ruled Nepal for many centuries.[34] Various sources mention up to 32 Kirati kings.[35]

Around 500 BCE, small kingdoms and confederations of clans arose in the southern regions of Nepal. From one of these, the Shakya polity, arose a prince who later renounced his status to lead an ascetic life, founded Buddhism, and came to be known as Gautama Buddha (traditionally dated 563–483 BCE).[36]

By 250 BCE, the southern regions had come under the influence of the Maurya Empire of North India and later became a vassal state under the Gupta Empire in the 4th century CE.[36]

There is a quite detailed description of the kingdom of Nepal in the account of the renowned Chinese Buddhist pilgrim monk Xuanzang, dating from about 645 CE.[37][38] Stone inscriptions in the Kathmandu Valley are important sources for the history of Nepal.

The kings of the Lichhavi dynasty have been found to have ruled Nepal after the Kirat monarchical dynasty. The context that "Suryavansi Kshetriyas had established a new regime by defeating the Kirats" can be found in some genealogies and Puranas.[35] It is not clear yet when the Lichhavi dynasty was established in Nepal. According to the opinion of Baburam Acharya, the prominent historian of Nepal, Lichhavies established their independent rule by abolishing the Kirati state that prevailed in Nepal around 250 CE.[35]

The Licchavi dynasty went into decline in the late 8th century, and was followed by a Newar or Thakuri era. Thakuri kings ruled over the country up to the middle of the 12th century CE; King Raghav Dev is said to have founded the ruling dynasty in October 869 CE.[39] King Raghav Dev also started the Nepal Sambat.[40]

Medieval

In the early 12th century, leaders emerged in far western Nepal whose names ended with the Sanskrit suffix malla ("wrestler"). These kings consolidated their power and ruled over the next 200 years, until the kingdom splintered into two dozen petty states. Another Malla dynasty beginning with Jayasthiti emerged in the Kathmandu valley in the late 14th century, and much of central Nepal again came under a unified rule. In 1482, the realm was divided into three kingdoms: Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur.

Kingdom of Nepal (1768–2008)

.jpg)

In the mid-18th century, Prithvi Narayan Shah, a Gorkha king, set out to put together what would become present-day Nepal. He embarked on his mission by securing the neutrality of the bordering mountain kingdoms. After several bloody battles and sieges, notably the Battle of Kirtipur, he managed to conquer the Kathmandu Valley in 1769. A detailed account of Prithvi Narayan Shah's victory was written by Father Giuseppe, an eyewitness to the war.[41]

The Gorkha control reached its height when the North Indian territories of the Kumaon and Garhwal Kingdoms in the west to Sikkim in the east came under Nepalese control. A dispute with Tibet over the control of mountain passes and inner Tingri valleys of Tibet forced the Qing Emperor of China to start the Sino-Nepali War compelling the Nepali to retreat and pay heavy reparations to Peking.

Rivalry between the Kingdom of Nepal and the East India Company over the control of states bordering Nepal eventually led to the Anglo-Nepali War (1815–16). At first, the British underestimated the Nepali and were soundly defeated until committing more military resources than they had anticipated needing. They were greatly impressed by the valour and competence of their adversaries. Thus began the reputation of Gurkhas as fierce and ruthless soldiers. The war ended in the Sugauli Treaty, under which Nepal ceded recently captured lands as well as the right to recruit soldiers. Madhesis, having supported the East India Company during the war, had their lands gifted to Nepal.[42]

Factionalism inside the royal family led to a period of instability. In 1846, a plot was discovered revealing that the reigning queen had planned to overthrow Jung Bahadur Kunwar, a fast-rising military leader. This led to the Kot massacre; armed clashes between military personnel and administrators loyal to the queen led to the execution of several hundred princes and chieftains around the country. Jung Bahadur Kunwar emerged victorious and founded the Rana dynasty, later known as Jung Bahadur Rana. The king was made a titular figure, and the post of Prime Minister was made powerful and hereditary. The Ranas were staunchly pro-British and assisted them during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (and later in both World Wars). Some parts of the Terai region populated with non-Nepali peoples were gifted to Nepal by the British as a friendly gesture because of her military help to sustain British control in India during the rebellion. In 1923, the United Kingdom and Nepal formally signed an agreement of friendship that superseded the Sugauli Treaty of 1816.[42]

Legalized slavery was abolished in Nepal in 1924.[43] Nevertheless, an estimated 234,600 people are enslaved in modern-day Nepal, or 0.82% of the population.[44] Debt bondage even involving debtors' children has been a persistent social problem in the Terai. Rana rule was marked by tyranny, debauchery, economic exploitation and religious persecution.[45][46]

In the late 1940s, newly emerging pro-democracy movements and political parties in Nepal were critical of the Rana autocracy. Meanwhile, with the invasion of Tibet by China in the 1950s, India sought to counterbalance the perceived military threat from its northern neighbour by taking pre-emptive steps to assert more influence in Nepal. India sponsored both King Tribhuvan (ruled 1911–55) as Nepal's new ruler in 1951 and a new government, mostly comprising the Nepali Congress, thus terminating Rana hegemony in the kingdom.[42]

After years of power wrangling between the king and the government, King Mahendra (ruled 1955–72) scrapped the democratic experiment in 1959, and a "partyless" Panchayat system was made to govern Nepal until 1989, when the "Jan Andolan" (People's Movement) forced King Birendra (ruled 1972–2001) to accept constitutional reforms and to establish a multiparty parliament that took seat in May 1991.[47] In 1991–92, Bhutan expelled roughly 100,000 Bhutanese citizens of Nepali descent, most of whom have been living in seven refugee camps in eastern Nepal ever since.[48]

In 1996, the Communist Party of Nepal started a violent bid to replace the royal parliamentary system with a people's republic. This led to the long Nepali Civil War and more than 12,000 deaths.

On 1 June 2001, there was a massacre in the royal palace. King Birendra, Queen Aishwarya and seven other members of the royal family were killed. The alleged perpetrator was Crown Prince Dipendra, who allegedly committed suicide (he died three days later) shortly thereafter. This outburst was alleged to have been Dipendra's response to his parents' refusal to accept his choice of wife. Nevertheless, there is speculation and doubts among Nepali citizens about who was responsible.

Following the carnage, King Birendra's brother Gyanendra inherited the throne. On 1 February 2005, King Gyanendra dismissed the entire government and assumed full executive powers to quash the violent Maoist movement,[47] but this initiative was unsuccessful because a stalemate had developed in which the Maoists were firmly entrenched in large expanses of countryside but could not yet dislodge the military from numerous towns and the largest cities. In September 2005, the Maoists declared a three-month unilateral ceasefire to negotiate.

In response to the 2006 democracy movement, King Gyanendra agreed to relinquish sovereign power to the people. On 24 April 2006 the dissolved House of Representatives was reinstated. Using its newly acquired sovereign authority, on 18 May 2006 the House of Representatives unanimously voted to curtail the power of the king and declared Nepal a secular state, ending its time-honoured official status as a Hindu Kingdom. On 28 December 2007, a bill was passed in parliament to amend Article 159 of the constitution – replacing "Provisions regarding the King" by "Provisions of the Head of the State" – declaring Nepal a federal republic, and thereby abolishing the monarchy.[49] The bill came into force on 28 May 2008.[50]

Republic of Nepal (2008–present)

The Unified Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) won the largest number of seats in the Constituent Assembly election held on 10 April 2008, and formed a coalition government, which included most of the parties in the CA. Although acts of violence occurred during the pre-electoral period, election observers noted that the elections themselves were markedly peaceful and "well-carried out".[51]

The newly elected Assembly met in Kathmandu on 28 May 2008, and, after a polling of 564 constituent Assembly members, 560 voted to form a new government,[50] with the monarchist Rastriya Prajatantra Party, which had four members in the assembly, registering a dissenting note. At that point, it was declared that Nepal had become a secular and inclusive democratic republic,[52][53] with the government announcing a three-day public holiday from 28–30 May. The king was thereafter given 15 days to vacate Narayanhity Palace so it could reopen as a public museum.[54]

Nonetheless, political tensions and consequent power-sharing battles have continued in Nepal. In May 2009, the Maoist-led government was toppled and another coalition government with all major political parties barring the Maoists was formed.[55] Madhav Kumar Nepal of the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) was made the Prime Minister of the coalition government.[56] In February 2011 the Madhav Kumar Nepal Government was toppled and Jhala Nath Khanal of the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) was made the Prime Minister.[57] In August 2011 the Jhala Nath Khanal Government was toppled and Baburam Bhattarai of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) was made the Prime Minister.[58]

The political parties were unable to draft a constitution in the stipulated time.[59] This led to dissolution of the Constituent Assembly to pave way for new elections to strive for a new political mandate. In opposition to the theory of separation of powers, then Chief Justice Khil Raj Regmi was made the chairman of the caretaker government. Under Regmi, the nation saw peaceful elections for the constituent assembly. The major forces in the earlier constituent assembly (namely CPN Maoists and Madhesi parties) dropped to distant 3rd and even below.[60][61]

In February 2014, after consensus was reached between the two major parties in the constituent assembly, Sushil Koirala was sworn in as the new prime minister of Nepal.[62][63]

On 25 April 2015, a magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck Nepal.[64] Two weeks later, on 12 May, another earthquake with a magnitude of 7.3 hit Nepal, which left more than 8,500 people dead and about 21,000 injured.[65]

In 20 September 2015, a new constitution, the "Constitution of Nepal 2015" (Nepali: नेपालको संविधान २०७२) was announced by President Ram Baran Yadav in the constituent assembly. The constituent assembly was transformed into a legislative parliament by the then-chairman of that assembly. The new constitution of Nepal has changed Nepal practically into a federal democratic republic by making 7 unnamed states.

In October 2015, Bidhya Devi Bhandari was nominated as the first female president.[66]

Geography

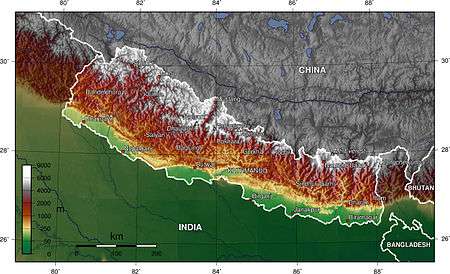

Nepal is of roughly trapezoidal shape, 800 kilometres (500 mi) long and 200 kilometres (120 mi) wide, with an area of 147,181 km2 (56,827 sq mi). See [[List of political and geographic subdivisions by total area from 100,000 to 1,000,000 km<sup>2</sup> | List of territories by size]] for the comparative size of Nepal. It lies between latitudes 26° and 31°N, and longitudes 80° and 89°E.

Nepal is commonly divided into three physiographic areas: Himal, Pahad and Terai. These ecological belts run east–west and are vertically intersected by Nepal's major, north to south flowing river systems.

The southern lowland plains or Terai bordering India are part of the northern rim of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. Terai is a lowland region containing some hill ranges. The plains were formed and are fed by three major Himalayan rivers: the Kosi, the Narayani, and the Karnali as well as smaller rivers rising below the permanent snowline. This region has a subtropical to tropical climate. The outermost range of foothills called Sivalik Hills or Churia Range, cresting at 700 to 1,000 metres (2,300 to 3,280 ft), marks the limit of the Gangetic Plain; however broad, low valleys called Inner Tarai Valleys (Bhitri Tarai Uptyaka) lie north of these foothills in several places.

Pahad is a mountain region that does not generally contain snow. The mountains vary from 800 to 4,000 metres (2,600 to 13,100 ft) in altitude with progression from subtropical climates below 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) to alpine climates above 3,600 metres (11,800 ft). The Lower Himalayan Range, reaching 1,500 to 3,000 metres (4,900 to 9,800 ft), is the southern limit of this region, with subtropical river valleys and "hills" alternating to the north of this range. Population density is high in valleys but notably less above 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) and very low above 2,500 metres (8,200 ft), where snow occasionally falls in winter.

Himal is the mountain region containing snow and situated in the Great Himalayan Range; it makes up the northern part of Nepal. It contains the highest elevations in the world including 8,848 metres (29,029 ft) height Mount Everest (Sagarmāthā in Nepali) on the border with China. Seven other of the world's "eight-thousanders" are in Nepal or on its border with China: Lhotse, Makalu, Cho Oyu, Kangchenjunga, Dhaulagiri, Annapurna and Manaslu.

Climate

Nepal has five climatic zones, broadly corresponding to the altitudes. The tropical and subtropical zones lie below 1,200 metres (3,900 ft), the temperate zone 1,200 to 2,400 metres (3,900 to 7,900 ft), the cold zone 2,400 to 3,600 metres (7,900 to 11,800 ft), the subarctic zone 3,600 to 4,400 metres (11,800 to 14,400 ft), and the Arctic zone above 4,400 metres (14,400 ft).

Nepal experiences five seasons: summer, monsoon, autumn, winter and spring. The Himalaya blocks cold winds from Central Asia in the winter and forms the northern limit of the monsoon wind patterns. In a land once thickly forested, deforestation is a major problem in all regions, with resulting erosion and degradation of ecosystems.

Nepal is popular for mountaineering, having some of the highest and most challenging mountains in the world, including Mount Everest. Technically, the southeast ridge on the Nepali side of the mountain is easier to climb, so most climbers prefer to trek to Everest through Nepal.

| Mountain | Height | Section | Location | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mount Everest (Highest in world) |

8,848 m | 29,029 ft | Khumbu Mahalangur | Khumjung VDC, Solukhumbu District, Sagarmatha Zone (Nepal-China Border) | |

| Kangchenjunga (3rd highest) |

8,586 m | 28,169 ft | Northern Kanchenjunga | Lelep VDC / Yamphudin VDC, Taplejung District, Mechi Zone (Nepal-Sikkim Border) | |

| Lhotse (4th highest) |

8,516 m | 27,940 ft | Everest Group | Khumjung VDC, Solukhumbu District, Sagarmatha Zone (Nepal-China Border) | |

| Makalu (5th highest) |

8,462 m | 27,762 ft | Makalu Mahalangur | Makalu VDC, Sankhuwasabha District, Kosi Zone (Nepal-China Border) | |

| Cho Oyu (6th highest) |

8,201 m | 26,906 ft | Khumbu Mahalangur | Khumjung VDC, Solukhumbu District, Sagarmatha Zone (Nepal-China Border) | |

| Dhaulagiri (7th highest) |

8,167 m | 26,795 ft | Dhaulagiri | Mudi VDC / Kuinemangale VDC, Myagdi District, Dhawalagiri Zone | |

| Manaslu (8th highest) |

8,156 m | 26,759 ft | Mansiri | Samagaun VDC, Gorkha District / Dharapani VDC, Manang District, Gandaki Zone | |

| Annapurna (10th highest) |

8,091 m | 26,545 ft | Annapurna | Ghandruk VDC, Kaski District, Gandaki Zone / Narchyang VDC, Myagdi District, Dhawalagiri Zone | |

Geology

The collision between the Indian subcontinent and Eurasia, which started in the Paleogene period and continues today, produced the Himalaya and the Tibetan Plateau. Nepal lies completely within this collision zone, occupying the central sector of the Himalayan arc, nearly one third of the 2,400 km (1,500 mi)-long Himalayas.[68][69][70][71][72][73]

The Indian plate continues to move north relative to Asia at about 50 mm (2.0 in) per year.[74] This is about twice the speed at which human fingernails grow, which is very fast given the size of the blocks of Earth's crust involved. As the strong Indian continental crust subducts beneath the relatively weak Tibetan crust, it pushes up the Himalayan Mountains. This collision zone has accommodated huge amounts of crustal shortening as the rock sequences slide one over another.

Based on a study published in 2014, of the Main Frontal Thrust, on average a great earthquake occurs every 750 ± 140 and 870 ± 350 years in the east Nepal region.[75] A study from 2015 found a 700-year delay between earthquakes in the region. The study also suggests that because of tectonic stress transfer, the earthquake from 1934 in Nepal and the 2015 earthquake are connected – following a historic earthquake pattern.[76]

Erosion of the Himalayas is a very important source of sediment, which flows to the Indian Ocean via several great rivers: the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra River systems.[77]

Environment

The dramatic differences in elevation found in Nepal result in a variety of biomes, from tropical savannas along the Indian border, to subtropical broadleaf and coniferous forests in the Hill Region, to temperate broadleaf and coniferous forests on the slopes of the Himalaya, to montane grasslands and shrublands and rock and ice at the highest elevations.

At the lowest elevations is the Terai-Duar savanna and grasslands ecoregion. These form a mosaic with the Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests, which occur from 500 to 1,000 metres (1,600 to 3,300 ft) and include the Inner Terai Valleys. Himalayan subtropical pine forests occur between 1,000 and 2,000 metres (3,300 and 6,600 ft).

Above these elevations, the biogeography of Nepal is generally divided from east to west by the Gandaki River. Ecoregions to the east tend to receive more precipitation and to be more species-rich. Those to the west are drier with fewer species.

From 1,500 to 3,000 metres (4,900 to 9,800 ft), are temperate broadleaf forests: the eastern and western Himalayan broadleaf forests. From 3,000 to 4,000 metres (9,800 to 13,100 ft) are the eastern and western Himalayan subalpine conifer forests. To 5,500 metres (18,000 ft) are the eastern and western Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows.

- Landscapes and Climates of Nepal

NASA Landsat-7 Image of Nepal. Nepal shares its boundaries with India and China

NASA Landsat-7 Image of Nepal. Nepal shares its boundaries with India and China Mount Everest, the highest peak on earth, lies on the Nepal-China border

Mount Everest, the highest peak on earth, lies on the Nepal-China border Barun Valley, one of many valleys in the Himalaya created by glacier flows.

Barun Valley, one of many valleys in the Himalaya created by glacier flows. View of Khartuwa village from Thakuri village of Sitalpati, Shankhuwasabha, eastern Nepal.

View of Khartuwa village from Thakuri village of Sitalpati, Shankhuwasabha, eastern Nepal.- The Annapurna range of the Himalayas.

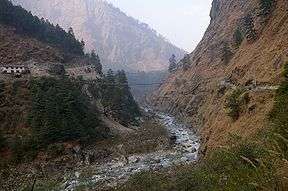

Kali Gandaki Gorge is one of the deepest gorges on earth.

Kali Gandaki Gorge is one of the deepest gorges on earth..jpg) Marshyangdi Valley

Marshyangdi Valley Wind erosion in Kalopani

Wind erosion in Kalopani A field in Terai

A field in Terai Phulchowki Hill

Phulchowki Hill Hills view of Ghorahi, Dang

Hills view of Ghorahi, Dang View of mountains

View of mountains Cascade view of mountains from Jiri, Nepal

Cascade view of mountains from Jiri, Nepal View of mountain from Jiri, Nepal

View of mountain from Jiri, Nepal

Politics

Nepal has seen rapid political changes during the last three decades. Up until 1990, Nepal was a monarchy under executive control of the King. Faced with a communist movement against absolute monarchy, King Birendra, in 1990, agreed to a large-scale political reform by creating a parliamentary monarchy with the king as the head of state and a prime minister as the head of the government.

Nepal's legislature was bicameral, consisting of a House of Representatives called the Pratinidhi Sabha and a National Council called the Rastriya Sabha. The House of Representatives consisted of 205 members directly elected by the people. The National Council had 60 members: ten nominated by the king, 35 elected by the House of Representatives, and the remaining 15 elected by an electoral college made up of chairs of villages and towns. The legislature had a five-year term but was dissolvable by the king before its term could end. All Nepali citizens 18 years and older became eligible to vote.

The executive comprised the King and the Council of Ministers (the cabinet). The leader of the coalition or party securing the maximum seats in an election was appointed as the Prime Minister. The Cabinet was appointed by the king on the recommendation of the Prime Minister. Governments in Nepal tended to be highly unstable, falling either through internal collapse or parliamentary dissolution by the monarch, on the recommendation of the prime minister, according to the constitution; no government has survived for more than two years since 1991.

A popular democratic movement in April 2006 brought about a change in the nation's governance: an interim constitution was promulgated, with the King giving up power, and an interim House of Representatives was formed with Maoist members after the new government held peace talks with the Maoist rebels. The number of parliamentary seats was also increased to 330. In April 2007, the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) joined the interim government of Nepal.

In December 2007, the interim parliament passed a bill making Nepal a federal republic, with a president as head of state. Elections for the constitutional assembly were held on 10 April 2008; the Maoist party led the results but did not achieve a simple majority of seats.[78] The new parliament adopted the 2007 bill at its first meeting by an overwhelming majority, and King Gyanendra was given 15 days to leave the Royal Palace in central Kathmandu. He left on 11 June.[79]

On 26 June 2008, the prime minister Girija Prasad Koirala, who had served as Acting Head of State since January 2007, announced that he would resign on the election of the country's first president by the Constituent Assembly. The first round of voting, on 19 July 2008, saw Parmanand Jha win election as Nepali vice-president, but neither of the contenders for president received the required 298 votes and a second round was held two days later. Ram Baran Yadav of the Nepali Congress party defeated Maoist-backed Ram Raja Prasad Singh with 308 of the 590 votes cast.[80] Koirala submitted his resignation to the new president after Yadav's swearing-in ceremony on 23 July 2008.

On 15 August 2008, Maoist leader Prachanda (Pushpa Kamal Dahal) was elected Prime Minister of Nepal, the first since the country's transition from a monarchy to a republic. On 4 May 2009, Dahal resigned over on-going conflicts with regard to the sacking of the Army chief. Since Dahal's resignation, the country has been in a serious political deadlock with one of the big issues being the proposed integration of the former Maoist combatants, also known as the People's Liberation Army, into the national security forces.[81] After Dahal, Jhala Nath Khanal of CPN (UML) was elected the Prime Minister. Khanal was forced to step down as he could not succeed in carrying forward the Peace Process and the constitution writing. On August 2011, Maoist Babu Ram Bhattarai became third Prime Minister after the election of constituent assembly.[82] On 24 May 2012, Nepals's Deputy PM Krishna Sitaula resigned.[83] On 27 May 2012, the country's Constituent Assembly failed to meet the deadline for writing a new constitution for the country. Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai announced that new elections would be held thar later year. "We have no other option but to go back to the people and elect a new assembly to write the constitution," he said in a nationally televised speech. One of the main obstacles has been disagreement over whether the states that will be created will be based on ethnicity.[84] This election was delayed by the Election Commission for a year, eventually occurring in late 2013 and electing the country's Second Constituent Assembly. This assembly promulgated the extant Constitution of Nepal in 2015.

Nepal is one of the few countries in Asia to abolish the death penalty.[85] Nepal is the only Asian country where the possibility of same-sex marriage has been proposed in the high court and in the legislature although same-sex marriage currently does not exist in Nepal (see also LGBT rights in Nepal and Same-sex marriage in Nepal). The decision was based on a seven-person government committee study, and enacted through Supreme Court's ruling November 2008. The ruling granted full rights for LGBT individuals, including the right to marry,[86] and Nepalese now can get citizenship as a third gender rather than male or female as authorised by Nepal's Supreme Court in 2007.[87]

Government

Nepal is governed according to the Constitution of Nepal, which came into effect on 20 September 2015, replacing the Interim Constitution of 2007. The Constitution was drafted by the Second Constituent Assembly following the failure of the First Constituent Assembly to produce a constitution in its mandated period. The constitution is the fundamental law of Nepal. It defines Nepal as having multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-religious, multi-cultural characteristics with common aspirations of people living in diverse geographical regions, and being committed to and united by a bond of allegiance to the national independence, territorial integrity, national interest, and prosperity of Nepal. All Nepali people collectively constitute the nation.

The Constitution of Nepal has defined three organs of the government.[88]

- Executive: The form of governance of Nepal is a multi-party, competitive, federal democratic republican parliamentary system based on plurality. The executive power of Nepal rests with the Council of Ministers in accordance with the Constitution and Nepali law. The President appoints the parliamentary party leader of the political party with the majority in the House of Representatives as a Prime Minister, and a Council of Ministers is formed in his/her chairmanship. The executive power of the provinces, pursuant to the Constitution and laws, is vested in the Council of Ministers of the province. The executive power of the province shall be exercised by the province Head in case of absence of the province Executive in a State of Emergency or enforcement of Federal rule. Every province has a ceremonial Head as the representative of the Federal government. The President appoints a Governor for every province. The Governor exercises the rights and duties as specified in the constitution or laws. The Governor appoints the leader of the parliamentary party with the majority in the Provincial Assembly as the Chief Minister and the Council of Ministers are formed under the chairpersonship of the Chief Minister.

- Legislative: The Legislature of Nepal, called Federal Parliament, consisting of two Houses, namely the House of Representatives and the National Assembly. Except when dissolved earlier, the term of House of Representatives is five years. The House of Representatives consist of 275 members: 165 members elected through the first-past-the-post electoral system consisting of one member from each of the one hundred and sixty five electoral constituencies formed by dividing Nepal into 165 constituencies based on geography and population; 110 elected from proportional representation electoral system where voters vote for parties, while treating the whole country as a single electoral constituency. The National Assembly is a permanent house. The tenure of members of National Assembly is six years. The National Assembly consists of 59 members: 56 members elected from an Electoral College, comprising members of provincial Assembly and chairpersons and vice-chairpersons of Village councils and Mayors and Deputy Mayors of Municipal councils, with different weights of votes for each, with eight members from each state, including at least three women, one Dalit, and one person with a disability or a member of a minority. 3 members, including at least one woman, are to be nominated by the President on the recommendation of the Government of Nepal. A Pradesh Sabha or Provincial Assembly is the unicameral legislative assembly for a federal province.[89] The term for the Provincial Assembly is five years, except when dissolved earlier.

- Judicial: Powers relating to justice in Nepal are exercised by courts and other judicial institutions in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution, other laws, and recognised principles of justice. Nepal has a unitary three-tier independent judiciary that comprises the Supreme Court, headed by the Chief Justice of Nepal, 7 High Courts, and a large number of trial courts.

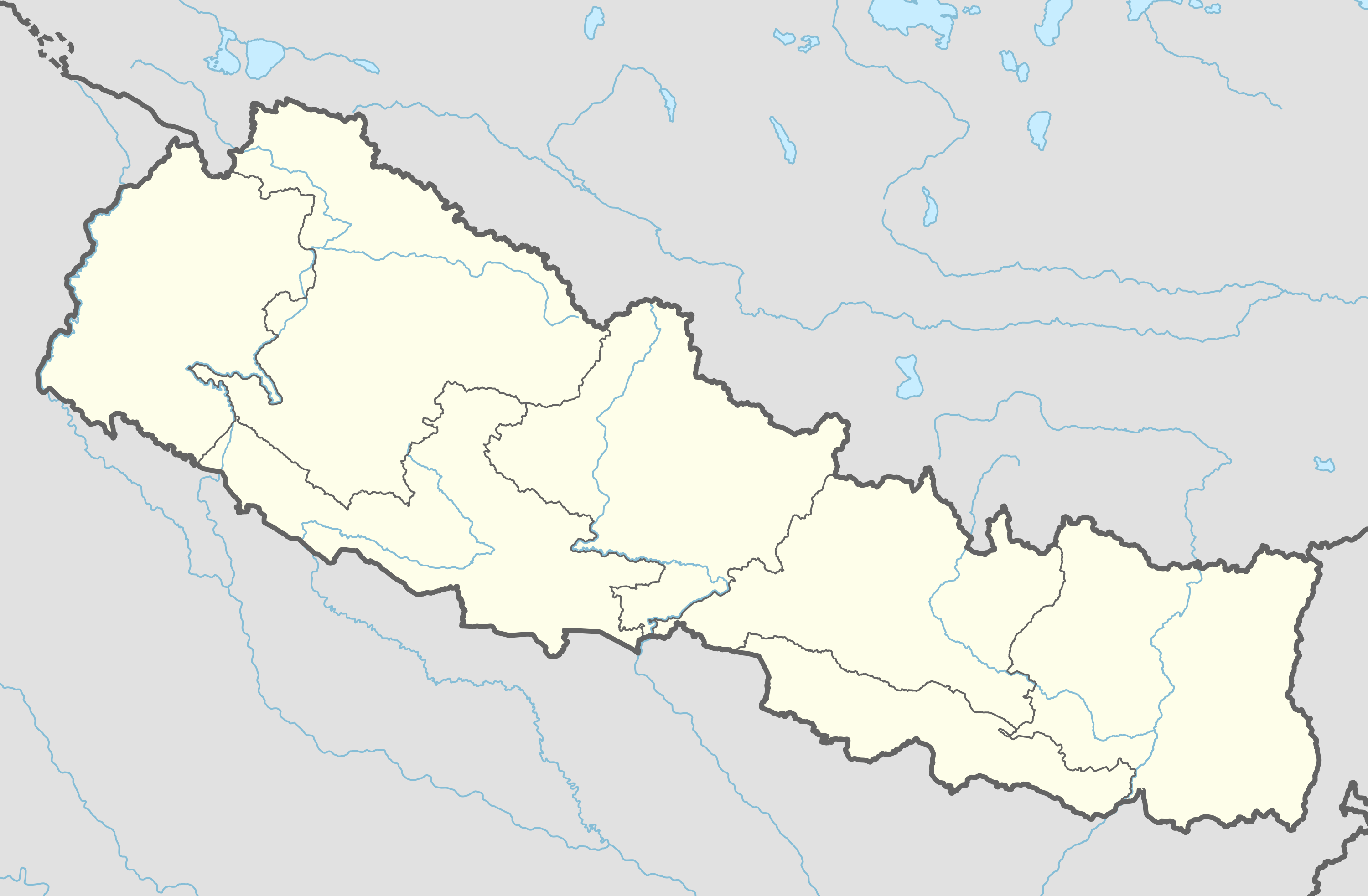

Administrative divisions

As of 3 April 2018, Nepal is divided into 7 provinces and 77 districts. It has 753 local units. There are 6 metropolises, 11 sub-metropolises, 276 municipal councils, and 460 village councils for official works. The constitution grants 22 absolute powers to the local units while they share 15 more powers with the central and state governments.[90]

| No. | Provinces | Capital | Districts | Area (km2) |

Population (2011) |

Density (people/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Province No. 1 | Biratnagar | 14 | 25,905 km2 | 4,534,943 | 175 |

| 2 | Province No. 2 | Janakpur | 8 | 9,661 km2 | 5,404,145 | 559 |

| 3 | Province No. 3 | Hetauda | 13 | 20,300 km2 | 5,529,452 | 272 |

| 4 | Gandaki Pradesh | Pokhara | 11 | 21,504 km2 | 2,413,907 | 112 |

| 5 | Province No. 5 | Butwal | 12 | 22,288 km2 | 4,891,025 | 219 |

| 6 | Karnali Pradesh | Birendranagar | 10 | 27,984 km2 | 1,168,515 | 41 |

| 7 | Sudurpashchim Pradesh | Godavari | 9 | 19,539 km2 | 2,552,517 | 130 |

| Total | Nepal | Kathmandu | 77 | 147,181 km2 | 26,494,504 | 180 |

Foreign relations and military

Nepal has close ties with both of its neighbors, India and China. In accordance with a long-standing treaty, Indian and Nepali citizens may travel to each other's countries without a passport or visa. Nepali citizens may work in India without legal restriction. The Indian Army maintains seven Gorkha regiments consisting of Gorkha troops recruited mostly from Nepal.

However, in the years since the Government of Nepal has been communised and dominated by socialists, and India's government has been controlled by more right-wing parties, India has been remilitarising the "porous" Indo-Nepali border to stifle the flow of Islamist groups.[91]

Nepal established relations with the People's Republic of China on 1 August 1955, and relations since have been based on the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence. Nepal has aided China in the aftermath of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, and China has provided economic assistance for Nepali infrastructure. Both countries have cooperated to host the 2008 Summer Olympics summit of Mt. Everest.[92] Nepal has assisted in curbing anti-China protests from the Tibetan diaspora.[93]

Nepal's military consists of the Nepali Army, which includes the Nepali Army Air Service. The Nepali Police Force is the civilian police and the Armed Police Force Nepal[94] is the paramilitary force. Service is voluntary and the minimum age for enlistment is 18 years. Nepal spends $99.2 million (2004) on its military—1.5% of its GDP. Much of the equipment and arms are imported from India. Consequently, the US provided M16s, M4s, and other Colt weapons to combat communist (Maoist) insurgents. The standard-issue battle rifle of the Nepali army is the Colt M16.[95]

In the new regulations by Nepali Army, female soldiers have been barred from participating in combat situations and fighting in the frontlines of war. However, they are allowed to be a part of the army in sections like intelligence, headquarters, signals, and operations.[96]

Economy

.jpg)

Nepal's gross domestic product (GDP) for 2012 was estimated at over $17.921 billion (adjusted to nominal GDP).[9] In 2010, agriculture accounted for 36.1%, services comprised 48.5%, and industry 15.4% of Nepal's GDP.[97] While agriculture and industry are contracting, the contribution by the service sector is increasing.[97][98]

Agriculture employs 76% of the workforce, services 18% and manufacturing and craft-based industry 6%. Agricultural produce – mostly grown in the Terai region bordering India – includes tea, rice, corn, wheat, sugarcane, root crops, milk, and water buffalo meat. Industry mainly involves the processing of agricultural produce, including jute, sugarcane, tobacco, and grain. Its workforce of about 10 million suffers from a severe shortage of skilled labour.

Nepal's economic growth continues to be adversely affected by the political uncertainty. Nevertheless, real GDP growth was estimated to increase to almost 5 percent for 2011–2012. This is an improvement from the 3.5 percent GDP growth in 2010–2011 and would be the second-highest growth rate in the post-conflict era.[99] Sources of growth include agriculture, construction, financial and other services. The contribution of growth by consumption fuelled by remittances has declined since 2010/2011. While remittance growth slowed to 11 percent (in Nepali Rupee terms) in 2010/2011, it has since increased to 37 percent. Remittances are estimated to be equivalent to 25–30 percent of GDP. Inflation has been reduced to a three-year low of 7 percent.[99]

The proportion of poor people has declined substantially since 2003. The percentage of people living below the international poverty line (people earning less than US$1.25 per day) has halved in seven years.[99] At this measure of poverty the percentage of poor people declined from 53.1% in 2003/2004 to 24.8% in 2010/2011.[99] With a higher poverty line of US$2 per-capita per day, poverty declined by one-quarter to 57.3%.[99] However, the income distribution remains grossly uneven.[100]

In a recent survey, Nepal has performed extremely well in reducing poverty along with Rwanda and Bangladesh as the percentage of poor dropped to 44.2 percent of the population in 2011 from 64.7 percent in 2006—4.1 percentage points per year, which means that Nepal has made improvement in sectors like nutrition, child mortality, electricity, improved flooring and assets. If the progress of reducing poverty continues at this rate, then it is predicted that Nepal will halve the current poverty rate and eradicate it within the next 20 years.[101][102]

The spectacular landscape and diverse, exotic cultures of Nepal represent considerable potential for tourism, but growth in the industry has been stifled by political instability and poor infrastructure. Despite these problems, in 2012 the number of international tourists visiting Nepal was 598,204, a 10% increase on the previous year.[103] The tourism sector contributed nearly 3% of national GDP in 2012 and is the second-biggest foreign income earner after remittances.[104]

The rate of unemployment and underemployment approaches half of the working-age population. Thus many Nepali citizens move to other countries in search of work. Destinations include India, Qatar, the United States, Thailand, the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Brunei Darussalam, Australia, and Canada.[105][106] Nepal receives $50 million a year through the Gurkha soldiers who serve in the Indian and British armies and are highly esteemed for their skill and bravery. As of 2010, the total remittance value is around $3.5 billion.[106] In 2009 alone, the remittance contributed to 22.9% of the nation's GDP.[106]

A long-standing economic agreement underpins a close relationship with India. The country receives foreign aid from the UK,[107][108] India, Japan, the US, the EU, China, Switzerland, and Scandinavian countries. Poverty is acute; per-capita income is around $1,000.[109] The distribution of wealth among the Nepali is consistent with that in many developed and developing countries: the highest 10% of households control 39.1% of the national wealth and the lowest 10% control only 2.6%.

The government's budget is about $1.153 billion, with an expenditure of $1.789 billion (FY 20005/06). The Nepali rupee has been tied to the Indian rupee at an exchange rate of 1.6 for many years. Since the loosening of exchange rate controls in the early 1990s, the black market for foreign exchange has all but disappeared. The inflation rate has dropped to 2.9% after a period of higher inflation during the 1990s.

Nepal's exports of mainly carpets, clothing, hemp, leather goods, jute goods and grain total $822 million. Import commodities of mainly gold, machinery and equipment, petroleum products and fertiliser total US$2 billion. European Union (EU) (46.13%), the US (17.4%), and Germany (7.1%) are its main export partners. The European Union has emerged the largest buyer of Nepali ready-made garments (RMG). Exports to the EU accounted for "46.13 percent of the country's total garment exports".[110] Nepal's import partners include India (47.5%), the United Arab Emirates (11.2%), China (10.7%), Saudi Arabia (4.9%), and Singapore (4%).

Besides having landlocked, rugged geography, few tangible natural resources and poor infrastructure, the ineffective post-1950 government and the long-running civil war are also factors in stunting the nation's economic growth and development.[111][112][113]

Infrastructure

Energy

The bulk of the energy in Nepal comes from fuel wood (68%), agricultural waste (15%), animal dung (8%), and imported fossil fuels (8%).[114][115] Except for some lignite deposits, Nepal has no known oil, gas or coal deposits. All commercial fossil fuels (mainly oil and coal) are either imported from India or from international markets routed through India and China. Fuel imports absorb over one-fourth of Nepal's foreign exchange earnings.[115]

Only about 1% energy need is fulfilled by electricity. The perennial nature of Nepali rivers and the steep gradient of the country's topography provide ideal conditions for the development of some of the world's largest hydroelectric projects. Current estimates put Nepal's economically feasible hydropower potential to be approximately 83,000 MW from 66 hydropower project sites.[115][116] However, currently Nepal has been able to exploit only about 600 MW from 20 medium to large hydropower plants and a number of small and micro hydropower plants.[114] There are 9 major hydropower plants under construction, and additional 27 sites considered for potential development.[114] Only about 40% of Nepal's population has access to electricity.[114] There is a great disparity between urban and rural areas. The electrification rate in urban areas is 90%, whereas the rate for rural areas is only 5%.[115] Power cuts of up to 22 hours a day take place in peak demand periods of winter and the peak electricity demand is almost the double the capability or dependable capacity.[117] The position of the power sector remains unsatisfactory because of high tariffs, high system losses, high generation costs, high overheads, over staffing, and lower domestic demand.[115]

Transport

Nepal remains isolated from the world's major land, air and sea transport routes although, within the country, aviation is in a better state, with 47 airports, 11 of them with paved runways;[118] flights are frequent and support a sizable traffic. The hilly and mountainous terrain in the northern two-thirds of the country has made the building of roads and other infrastructure difficult and expensive. In 2007 there were just over 10,142 km (6,302 mi) of paved roads, and 7,140 km (4,437 mi) of unpaved road, and one 59 km (37 mi) railway line in the south.[118]

More than one-third of its people live at least a two hours walk from the nearest all-season road. Only recently all district headquarters (except for Simikot and Dunai) became reachable by road from Kathmandu. In addition, around 60% of the road network and most rural roads are not operable during the rainy season.[119] The only practical seaport of entry for goods bound for Kathmandu is Kolkata in West Bengal state of India. Internally, the poor state of development of the road system makes access to markets, schools, and health clinics a challenge.[111]

Telecommunications and mass media

According to the Nepal Telecommunication Authority MIS May 2012 report,[120] there are seven operators and the total voice telephony subscribers including fixed and mobile are 16,350,946, which gives a penetration rate of 61.42%. The fixed telephone service account for 9.37%, mobile for 64.63%, and other services (LM, GMPCS) for 3.76% of the total penetration rate. Similarly, the numbers of subscribers to data/internet services are 4,667,536, which represents 17.53% penetration rate. Most of the data service is accounted by GPRS users. Twelve months earlier the data/internet penetration was 10.05%, thus this represents a growth rate of 74.77%.[120]

Not only has there been strong subscriber growth, especially in the mobile sector, but there was evidence of a clear vision in the sector, including putting a reform process in place and planning for the building of necessary telecommunications infrastructure. Most importantly, the Ministry of Information and Communications (MoIC) and the telecom regulator, the National Telecommunications Authority (NTA), have both been very active in the performance of their respective roles.[121]

Despite all the effort, there remained a significant disparity between the high coverage levels in the cities and the coverage available in the underdeveloped rural regions. Progress on providing some minimum access had been good. Of a total of 3,914 village development committees across the country, 306 were unserved by December 2009.[121] In order to meet future demand, it was estimated that Nepal needed to invest around US$135 million annually in its telecom sector.[121] In 2009, the telecommunication sector alone contributed to 1% of the nation's GDP.[122] As of 30 September 2012, Nepal has 1,828,700 Facebook users.[123]

As of 2007, the state operates two television stations as well as national and regional radio stations. There are roughly 30 independent TV channels registered, with only about half in regular operation. Nearly 400 FM radio stations are licensed with roughly 300 operational.[118] According to the 2011 census, the percentage of households possessing radio was 50.82%, television 36.45%, cable TV 19.33%, computer 7.23%.[2] According to the Press Council Nepal, as of 2012 there are 2,038 registered newspapers in Nepal, among which 514 are in publication.[124] In 2013, Reporters Without Borders ranked Nepal at 118th place in the world in terms of press freedom.[125][126]

Science and technology

Historical kingdoms that existed in the Kathmandu valley are found to have made use of some clever technologies in numerous areas such as architecture, agriculture, civil engineering, water management, etc. The Gopals and Abhirs, who ruled the valley up until c. 1000 BC, used temporary materials for construction such as bamboo, hay, timber, etc. The Kirat period (700 BC – 110 AD) employed the technology of brick firing as well as produced quality woolen shawls. Similarly, stupas, idols, canals, self-recharging ponds, reservoirs, etc. constructed during the Lichhavi era (110–879 AD) are intact to this day, which manifests the ingenuity of traditional architecture. Moreover, the Malla period (1200–1768 AD) saw an impressive growth in architecture, on par with its advanced contemporaries. An archetypal example of Malla architecture is Nyatapola, a five-storied, 30-metre tall temple in Bhaktapur, which has strangely survived at least four major earthquakes, including the April 2015 Nepal earthquake.[127]

Nepal was a late entrant into the modern world of science and technology. Nepal’s first institution of higher education, Tri-Chandra College, was established by Chandra Shumsher in 1918. The college introduced science at the Intermediate level a year later, marking the genesis of formal science education in the country.[127] However, the college was not accessible to the general public, but only to a handful of members of the Rana regime. Throughout the Rana regime that lasted for well over a century, Nepal was effectively isolated from the rest of the world. Owing to this isolation, Nepal was relatively untouched by and unfamiliar of social transformations brought about by the British invasion in India and the Industrial Revolution in the West.[128] However, after the advent of democracy and abolition of Rana regime in 1951, Nepal broke free from the shackles of self-imposed isolation and opened up to the outside world. This opening marked the initiation of S&T activities in the country.[129]

An underdeveloped country, Nepal is plagued with problems such as poverty, illiteracy, unemployment, and the like. Consequently, science and technology have invariably lagged behind in the priority list of the government. On the other hand, citing poor university education at home, tens of thousands of Nepali students leave the country every year, with half of them never returning.[130][131] These factors have been huge deterrents to the development of science and technology in Nepal.

Community forestry

The Community Forestry Program in Nepal is a participatory environmental governance that encompasses well-defined policies, institutions, and practices. The program addresses the twin goals of forest conservation and poverty reduction. As more than 70 percent of Nepal's population depends on agriculture for their livelihood, community management of forests has been a critically important intervention. Through legislative developments and operational innovations over three decades, the program has evolved from a protection-oriented, conservation-focused agenda to a much more broad-based strategy for forest use, enterprise development, and livelihood improvement. By April 2009, one-third of Nepal's population was participating in the program, directly managing more than one-fourth of Nepal's forest area.[132][133]

The immediate livelihood benefits derived by rural households bolster strong collective action wherein local communities actively and sustainably manage forest resources. Community forests also became the source of diversified investment capital and raw material for new market-oriented livelihoods. Community forestry shows traits of political, financial, and ecological sustainability, including an emergence of a strong legal and regulatory framework, and robust civil society institutions and networks. However, a continuing challenge is to ensure equitable distribution of benefits to women and marginalised groups. Lessons for replication emphasise experiential learning, establishment of a strong civil society network, flexible regulation to encourage diverse institutional modalities, and responsiveness of government and policymakers to a multistakeholder collaborative learning process.[134][135]

Crime and law enforcement

Law enforcement in Nepal is primarily the responsibility of the Nepali Police Force, which is the national police of Nepal.[136] It is independent of the Nepali Army. In the days of its establishment, Nepal Police personnel were mainly drawn from the armed forces of the Nepali Congress Party that fought against the feudal Rana autocracy in Nepal. The Central Investigation Bureau (CIB) and National Investigation Department of Nepal (NID) are the investigation agencies of Nepal. They have offices in all 75 administrative districts, including regional offices in five regions and zonal offices in 14 zones. Numbers vary from three to five members at each district level in rural districts, and numbers can be higher in urban districts. They have both Domestic and International surveillance units, which mainly deals with cross border terrorists, drug trafficking and money laundering.[137][138][139][140]

A 2010 survey estimated about 46,000 hard drug users in the country, with 70% of the users to be within the age group of 15 to 29.[141] The same survey also reported that 19% of the users had been introduced to hard drugs when they were less than 15 years old; and 14.4% of drug users were attending school or college.[141] Only 12 of the 17 municipalities studied had any type of rehabilitation centre.[141][142] There has been a sharp increase in the seizure of drugs such as hashish, heroin and opium in the past few years; and there are indications that drug traffickers are trying to establish Nepal as a transit point.[143]

Human trafficking and child labour are major problems in Nepal.[144][145][146] Nepali victims are trafficked within Nepal, to India, the Middle East, and other areas such as Malaysia and forced to become prostitutes, domestic servants, beggars, factory workers, mine workers, circus performers, child soldiers, and others. Sex trafficking is particularly rampant within Nepal and to India, with as many as 5,000 to 10,000 women and girls trafficked to India alone each year.[147][148][149]

Capital punishment was abolished in Nepal in 1997.[150] In 2008, the Nepali government abolished the Haliya system of forced labour, freeing about 20,000 people.[151] However, the effectiveness of this has been questioned by the Asian Legal Resource Centre.[152]

Demographics

According to the 2011 census, Nepal's population grew from 9 million people in 1950 to 26.5 million. From 2001 to 2011, the average family size declined from 5.44 to 4.9. The census also noted some 1.9 million absentee people, over a million more than in 2001; most are male labourers employed overseas, predominantly in South Asia and the Middle East. This correlated with the drop in sex ratio from 94.41 as compared to 99.80 for 2001. The annual population growth rate is 1.35%.[2]

The citizens of Nepal are known as Nepali or Nepalese. The country is home to people of many different national origins. As a result, Nepalese do not equate their nationality with ethnicity, but with citizenship and allegiance. Although citizens make up the majority of Nepalese, non-citizen residents, dual citizens, and expatriates may also claim a Nepalese identity. Nepal is multicultural and multiethnic country because it became a country by occupying several small kingdoms such as Mustang, Videha (Mithila), Madhesh, and Limbuwan in the 18th century. The oldest settlements in Mithila and Tharuhat are Maithil. Northern Nepal is historically inhabited by Kirants Mongoloid, Rai and Limbu people. The mountainous region is sparsely populated above 3,000 m (9,800 ft), but in central and western Nepal ethnic Sherpa and Lamapeople inhabit even higher semi-arid valleys north of the Himalaya. The Nepali speaking Khas people mostly inhabit central and southern regions. Kathmandu Valley, in the middle hill region, constitutes a small fraction of the nation's area but is the most densely populated, with almost 5 percent of the nation's population. The Nepali are descendants of three major migrations from India, Tibet, and North Burma and the Chinese state of Yunnan via Assam. Among the earliest inhabitants were the Kirat of east mid-region, Newars of the Kathmandu Valley, aboriginal Tharus of Tharuhat,

Despite the migration of a significant section of the population to the Madhesh (southern plains) in recent years, the majority of Nepalese still live in the central highlands; the northern mountains are sparsely populated. Kathmandu, with a population of over 2.6 million (metropolitan area: 5 million), is the largest city in the country and the cultural and economic heart.

According to the World Refugee Survey 2008, published by the US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, Nepal hosted a population of refugees and asylum seekers in 2007 numbering approximately 130,000. Of this population, approximately 109,200 persons were from Bhutan and 20,500 from People's Republic of China.[153][154] The government of Nepal restricted Bhutanese refugees to seven camps in the Jhapa and Morang districts, and refugees were not permitted to work in most professions.[153] At present, the United States is working towards resettling more than 60,000 of these refugees in the US.[48]

| Data | Size |

|---|---|

| Population | 26,494,504 (2011) |

| Growth rate | 1.35% |

| Population below 14 Years old | 34.19% |

| Population of age 15 to 59 | 54.15% |

| Population above 60 | 8.13% |

| Median age (average) | 20.07 |

| Median age (male) | 19.91 |

| Median age (females) | 20.24 |

| Ratio (male:female) | 100:94.16 |

| Life expectancy (average) (reference:[155]) | 66.16 Years |

| Life expectancy (male) | 64.94 |

| Life expectancy (female) | 67.44 |

| Literacy rate (average) | 65.9% |

| Literacy rate (male) | 75.1% |

| Literacy rate (female) | 57.4% |

Languages

Nepal's diverse linguistic heritage stems from three major language groups: Indo-Aryan, Tibeto-Burman, and various indigenous language isolates. The major languages of Nepal (percent spoken as native language) according to the 2011 census are Nepali (44.6%), Maithili (11.7%), Bhojpuri (6.0%), Tharu (5.8%), Tamang (5.1%), Nepal Bhasa (3.2%), Bajjika (3%) and Magar (3.0%), Doteli (3.0%), Urdu (2.6%), Awadhi (1.89%), and Sunwar. Nepal is home to at least four indigenous sign languages.

Derived from Sanskrit, Nepali is written in Devanagari script. Nepali is the official language and serves as lingua franca among Nepali of different ethnolinguistic groups. The regional languages Maithili, Awadhi, Bhojpuri and rarely Urdu of Nepali Muslims are spoken in the southern Madhesh region. Many Nepali in government and business speak Maithili as the main language and Nepali as their de facto lingua franca. Varieties of Tibetan are spoken in and north of the higher Himalaya where standard literary Tibetan is widely understood by those with religious education. Local dialects in the Terai and hills are mostly unwritten with efforts underway to develop systems for writing many in Devanagari or the Roman alphabet.

Religion

The significant majority of the Nepalese population follows Hinduism. Shiva is regarded as the guardian deity of the country.[156] Nepal is home to the famous Lord Shiva temple, the Pashupatinath Temple, where Hindus from all over the world come for pilgrimage. According to Hindu mythology, the goddess Sita of the epic Ramayana, was born in the Mithila Kingdom of King Janaka Raja.

Lumbini is a Buddhist pilgrimage site and UNESCO World Heritage Site in the Kapilavastu district. Traditionally it is held to be the birthplace in about 563 B.C. of Siddhartha Gautama, a Kshatriya caste prince of the Sakya clan, who as the Buddha Gautama, founded Buddhism.

The holy site of Lumbini is bordered by a large monastic zone, in which only monasteries can be built. All three main branches of Buddhism exist in Nepal and the Newa people have their own branch of the faith.[157] Buddhism is also the dominant religion of the thinly populated northern areas, which are mostly inhabited by Tibetan-related peoples, such as the Sherpa.

The Buddha, born as a Hindu, is also said to be a descendant of Vedic Sage Angirasa in many Buddhist texts.[158] The Buddha's family surname is associated with Gautama Maharishi.[159] Differences between Hindus and Buddhists have been minimal in Nepal due to the cultural and historical intermingling of Hindu and Buddhist beliefs. Moreover, traditionally Buddhism and Hinduism were never two distinct religions in the western sense of the word. In Nepal, the faiths share common temples and worship common deities. Among other natives of Nepal, those more influenced by Hinduism were the Magar, Sunwar, Limbu and Rai and the Gurkhas.[160] Hindu influence is less prominent among the Gurung, Bhutia, and Thakali groups who employ Buddhist monks for their religious ceremonies.[160] Most of the festivals in Nepal are Hindu.[161] The Machendrajatra festival, dedicated to Hindu Shaiva Siddha, is celebrated by many Buddhists in Nepal as a main festival.[162] As it is believed that Ne Muni established Nepal,[163] some important priests in Nepal are called "Tirthaguru Nemuni". Islam is a minority religion in Nepal, with 4.2% of the population being Muslim according to a 2006 Nepali census.[164] Mundhum, Christianity and Jainism are other minority faiths.[165]

Education

The overall literacy rate (for population age 5 years and above) increased from 54.1% in 2001 to 65.9% in 2011. The male literacy rate was 75.1% compared to the female literacy rate of 57.4%. The highest literacy rate was reported in Kathmandu district (86.3%) and lowest in Rautahat (41.7%).[2] While the net primary enrollment rate was 74% in 2005;[166] in 2009, that enrollment rate was 90%.[167]

However, increasing access to secondary education (grade 9–12) remains a major challenge, as evidenced by the low net enrollment rate of 24% at this level. More than half of primary students do not enter secondary schools, and only one-half of them complete secondary schooling. In addition, fewer girls than boys join secondary schools and, among those who do, fewer complete the 10th grade.[168]

Nepal has seven universities: Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu University, Pokhara University, Purbanchal University, Mahendra Sanskrit University, Far-western University, and Agriculture and Forestry University.[169] Some newly proposed universities are Lumbini Bouddha University, and Mid-Western University. Some fine scholarship has emerged in the post-1990 era.[170]

Health

Public health and health care services in Nepal are provided by both the public and private sectors and fare poorly by international standards. According to 2011 census, more than one-third (38.17%) of the total households do not have a toilet.[2] Tap water is the main source of drinking water for 47.78% of households, tube well/hand pump is the main source of drinking water for about 35% of households, while spout, uncovered well/kuwa, and covered well/kuwa are the main source for 5.74%, 4.71%, and 2.45% respectively.[2] Based on 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) data, Nepal ranked 139th in life expectancy in 2010 with the average Nepali living to 65.8 years.[171][172]

Diseases are more prevalent in Nepal than in other South Asian countries, especially in rural areas. Leading diseases and illnesses include diarrhea, gastrointestinal disorders, goitres, intestinal parasites, leprosy, visceral leishmaniasis and tuberculosis.[173] About 4 out of 1,000 adults aged 15 to 49 had human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and the HIV prevalence rate was 0.5%.[174][175] Malnutrition also remains very high: about 47% of children under five are stunted, 15 percent wasted, and 36 percent underweight, although there has been a declining trend for these rates over the past five years, they remain alarmingly high.[176] In spite of these figures, improvements in health care have been made, most notably in maternal-child health. In 2012, the under-five infant mortality was estimated to be 41 out of every 1000 children.[177][178] Overall Nepal's Human Development Index (HDI) for health was 0.77 in 2011, ranking Nepal 126 out of 194 countries, up from 0.444 in 1980.[179][180]

Largest cities

As Nepal is one of the developing or so called under developed country, like other things it's cities or urban areas are also increasing day by day. More than 20 % people lives in the urban area or simply in cities. Kathmandu is the largest city of Nepal. People of Kathmandu are lucky enough to travel in Aeroplane before any land transport. It is also called as the City of Temple as it has numerous temples of Hindus god and goddess and that's of Buddhism. It also have 5 UNESCO World Heritage Sites. It is one of the oldest city of South Asia. It is also the capital city of Nepal. It also have many palace and historically important sites such as Singha Durbar, The other largest cities of Nepal are Pokhara, Biratnagar, Lalitpur, Bharatpur, Birgunj, Dharan, Hetauda and Nepalgunj.

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kathmandu Pokhara |

1 | Kathmandu | Province No. 3 | 975,453 | 11 | Tulsipur | Province No. 5 | 141,528 |  Lalitpur  Bharatpur |

| 2 | Pokhara | Gandaki | 414,141 | 12 | Itahari | Province No. 1 | 140,517 | ||

| 3 | Lalitpur | Province No. 3 | 284,922 | 13 | Nepalgunj | Province No. 5 | 138,951 | ||

| 4 | Bharatpur | Province No. 3 | 280,502 | 14 | Butwal | Province No. 5 | 138,741 | ||

| 5 | Birgunj | Province No. 2 | 240,922 | 15 | Dharan | Province No. 1 | 137,705 | ||

| 6 | Biratnagar | Province No. 1 | 214,662 | 16 | Kalaiya | Province No. 2 | 123,659 | ||

| 7 | Janakpur | Province No. 2 | 159,468 | 17 | Jitpur Simara | Province No. 2 | 117,496 | ||

| 8 | Ghorahi | Province No. 5 | 156,164 | 18 | Mechinagar | Province No. 1 | 111,797 | ||

| 9 | Hetauda | Province No. 3 | 152,875 | 19 | Budhanilkantha | Province No. 3 | 107,918 | ||

| 10 | Dhangadhi | Sudurpashchim | 147,741 | 20 | Gokarneshwar | Province No. 3 | 107,351 | ||

Culture

Folklore is an integral part of Nepali society. Traditional stories are rooted in the reality of day-to-day life, tales of love, affection and battles as well as demons and ghosts and thus reflect local lifestyles, culture, and beliefs. Many Nepali folktales are enacted through the medium of dance and music.

Most houses in the rural lowlands of Nepal are made up of a tight bamboo framework and walls of a mud and cow-dung mix. These dwellings remain cool in summer and retain warmth in winter. Houses in the hills are usually made of unbaked bricks with thatch or tile roofing. At high elevations construction changes to stone masonry and slate may be used on roofs.

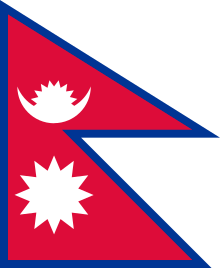

Nepal's flag is the only national flag in the world that is not rectangular in shape.[181] The constitution of Nepal contains instructions for a geometric construction of the flag.[182] According to its official description, the red in the flag stands for victory in war or courage, and is also the colour of the rhododendron, the national flower of Nepal. Red also stands for aggression. The flag's blue border signifies peace. The curved moon on the flag is a symbol of the peaceful and calm nature of Nepali, while the sun represents the aggressiveness of Nepali warriors.

Holidays and festivals

With 36 days a year, Nepal is the country that enjoys the most number of public holidays in the world.[183] The Nepali year begins in 1st of Baisakh in official Hindu Calendar of the country, the Bikram Sambat, which falls in mid-April and is divided into 12 months. Saturday is the official weekly holiday. Main annual holidays include the Martyr's Day (18 February), and a mix of Hindu and Buddhist festivals such as Dashain in autumn, Tihar in mid-autumn and Chhath in late autumn. During Swanti, the Newars perform the Mha Puja ceremony to celebrate New Year's Day of the lunar calendar Nepal Sambat. Being a Secular country Nepal has holiday on main festivals of minority religions in the nation too.[161]

Cuisine

The national cuisine of Nepal is Dhindo and Gundruk.The staple Nepali meal is dal bhat. Dal is a lentil soup, and is served over bhat (boiled rice), with tarkari (curried vegetables) together with achar (pickles) or chutni (spicy condiment made from fresh ingredients). It consists of non-vegetarian as well as vegetarian items. Mustard oil is a common cooking medium and a host of spices, including cumin, coriander, black pepper, sesame seeds, turmeric, garlic, ginger, methi (fenugreek), bay leaves, cloves, cinnamon, chilies and mustard seeds are used in cooking. Momo is a type of steamed dumpling with meat or vegetable fillings, and is a popular fast food in many regions of Nepal.

Sports

Association football is the most popular sport in Nepal[184] and was first played during the Rana dynasty in 1921.[185] The one and only international stadium in the country is the Dasarath Rangasala Stadium where the national team plays its home matches.[186]

Cricket has been gaining popularity since the last decade. Since the establishment of the national team, Nepal has played its home matches on the Tribhuvan University International Cricket Ground.[187] The national team has since won the 2012 ICC World Cricket League Division Four and the 2013 ICC World Cricket League Division Three[188] simultaneously, hence qualifying for 2014 Cricket World Cup Qualifier. They also qualified for the 2014 ICC World Twenty20 in Bangladesh,[189] and this qualification has been the farthest the team have ever made in an ICC event. On 28 June 2014, the ICC awarded T20I status to Nepal, who took part and performed exceptionally well in the 2014 ICC World Twenty20.[190][191] Nepal had already played three T20I matches before gaining the status, as ICC had earlier announced that all matches at the 2014 ICC World Twenty20 would have T20I status.[192] Nepal won the 2014 ICC World Cricket League Division Three held in Malaysia and qualified for the 2015 ICC World Cricket League Division Two.[193] Nepal finished fourth in the 2015 ICC World Cricket League Division Two in Namibia[194] and qualified for the 2015–17 ICC World Cricket League Championship.[195] But Nepal failed to secure promotion to Division One and qualification to 2015–17 ICC Intercontinental Cup after finishing third in the round-robin stage.[196][197] Basanta Regmi became the first bowler to take 100 wickets in the World Cricket League. He achieved this feat after taking 2 wickets against Netherlands in the tournament.[198] After finishing 2018 ICC World Cricket League Division Two at second place Nepal claims the place in 2018 Cricket World Cup Qualifier. On 15 March 2018 Nepal claimed One Day International (ODI) status for the first time with their win over Papua New Guinea in the 2018 Cricket World Cup Qualifier play off encounter.[199][200]

Units of measurement

Although the country has adopted the metric system as its official standard since 1968,[201] traditional units of measurement are still commonplace. The customary units of area employed in the Terai region – such as katha, bigha, etc. – sound similar to those used elsewhere in South Asia. However, they vary markedly in size, as they seem to have been standardised to different measures of area. For instance, a katha in Nepal is arbitrarily set at 338.63 m2, while a katha in Bangladesh means about 67 m2 of land area. In addition to native ones, imperial units pertaining to length (specifically inch and foot) and metric units such as kilogram and litre are also fairly common in everyday trade and commerce.

See also

References

- ↑ "Nepal". Ethnologue. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

all Regional languages are now considered national language of Nepal

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "National Population and Housing Census 2011 (National Report)" (PDF). Central Bureau of Statistics (Nepal). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- 1 2 2011 Nepal Census Report Archived 18 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Shrestha, Khadga Man (2005). "Religious Syncretism and Context of Buddhism in Modern Nepal". Voice of History. 20 (1): 51–60.

- ↑ "Krishna Bahadur Mahara elected Speaker". My Republica. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ↑ "Nepal5". Royalark.net. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ "Vote to curb Nepal king's powers". BBC. 18 May 2006. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ↑ "World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision". ESA.UN.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Nepal". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ↑ "Human Development Report" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2017. Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ↑ "Nepal". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "CIA – The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ "The World Factbook: Rank order population". CIA. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ Shaha (1992), p. 1.

- ↑ Lawoti, Mahendra; Hangen, Susan (1 January 2013). "Nationalism and Ethnic Conflict in Nepal: Identities and Mobilization After 1990". Routledge – via Google Books.

- ↑ Paul, T. V. (9 August 2010). "South Asia's Weak States: Understanding the Regional Insecurity Predicament". Stanford University Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ Acharya, Baburam (15 August 2013). "The Bloodstained Throne: Struggles for Power in Nepal (1775–1914)". Penguin UK – via Google Books.

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/31/world/asia/31iht-nepal.html?pagewanted=1&_r=2%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D

- ↑ "UK and Nepal celebrate 200 years of friendship – News stories – GOV.UK".

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ↑ Dangol, Amrit (6 May 2007). "Alone in Kathmandu". Alone in Kathmandu. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ↑ Prasad, P. 4 The life and times of Maharaja Juddha Shumsher Jung Bahadur Rana of Nepal

- ↑ Khatri, P. 16 The Postage Stamps of Nepal

- ↑ W.B., P. 34 Land of the Gurkhas

- ↑ Malla, Kamal P. "Nepala: Archaeology of the Word" (PDF). Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2011. Page 7.

- ↑ Malla, Kamal P. "Nepala: Archaeology of the Word" (PDF). Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2011. Page 1.

- ↑ Majupuria, Trilok Chandra; Majupuria, Indra (1979). Glimpses of Nepal. Maha Devi. p. 8. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ↑ Turner, Ralph L. (1931). "A Comparative and Etymological Dictionary of the Nepali Language". London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2011. Page 353.

- ↑ Hodgson, Brian H. (1874). "Essays on the Languages, Literature and Religion of Nepal and Tibet". London: Trübner & Co. Retrieved 8 May 2011. Page 51.

- ↑ Krishna P. Bhattarai (2009). Nepal. Infobase publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0523-9.

- 1 2 P. 17 Looking to the Future: Indo-Nepal Relations in Perspective By Lok Raj Baral

- ↑ "India-Nepal relations". gktoday.in. 18 November 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- 1 2 Singh, G.P. (1990). Kiratas in Ancient India. New Delhi: Gian Pub. House. OCLC 555770473.

- 1 2 3 http://www.telegraphnepal.com/national/2014-02-19/the-lichhavi-and-kirat-kings-of-nepal

- 1 2 "India-Nepal Relations – General Knowledge Today". www.gktoday.in.

- ↑ Li, Rongxi (translator). 1995. The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions, pp. 219–220. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. Berkeley, California. ISBN 1-886439-02-8

- ↑ Watters, Thomas. 1904-5. On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India (A.D. 629–645), pp. 83–85. Reprint: Mushiram Manoharlal Publishers, New Delhi. 1973.

- ↑ "Nepal Monarchy: Thakuri Dynasty".

- ↑ "Nepal Monarchy: Thakuri Dynasty". royalnepal.synthasite.com.

- ↑ Giuseppe, Father (1799). "Account of the Kingdom of Nepal". Asiatick Researches. London: Vernor and Hood. Retrieved 2 June 2012. p. 308.

- 1 2 3 lawrence, harris, george; division, library of congress. federal research; matles, savada, andrea. "Nepal and Bhutan : country studies".