Architecture of India

The architecture of India is rooted in its history, culture and religion. Indian architecture progressed with time and assimilated the many influences that came as a result of India's global discourse with other regions of the world throughout its millennia-old past. The architectural methods practiced in India are a result of examination and implementation of its established building traditions and outside cultural interactions.[1]

Though old, this Eastern tradition has also incorporated modern values as India became a modern nation-state. The economic reforms of 1991 further bolstered the urban architecture of India as the country became more integrated with the world's economy. Traditional Vastu Shastra remains influential in India's architecture during the contemporary era.[1]

Indus Valley Civilization (3300 BCE - 1700 BCE)

The Indus Valley Civilization (3300 BCE - 1700 BCE) covered a large area around the Indus River basin and beyond. In its mature phase, from about 2600 to 1900 BCE, it produced several cities marked by great uniformity within and between sites, including Harappa, Lothal, and the UNESCO World Heritage Site Mohenjo-daro. The civic and town planning and engineering aspects of these are remarkable, but the design of the buildings is "of a startling utilitarian character". There are granaries, drains, water-courses and tanks, but neither palaces nor temples have been identified, though cities have a central raised and fortified "citadel".[3] Mohenjo-daro has wells which may be the predecessors of the stepwell.[4] As many as 700 wells have been discovered in just one section of the city, leading scholars to believe that 'cylindrical brick lined wells' were invented by the Indus Valley Civilization.[4]

The architectural decoration is extremely minimal, though there are "narrow pointed niches" inside some buildings. Most of the art found is in miniature forms like seals, and mainly in terracotta, but there are a very few larger sculptures of figures. In most sites fired mud-brick (not sun-baked as in Mesopotamia) is used exclusively as the building material, but a few such as Dholavira are in stone. Most houses have two stories, and very uniform sizes and plans. The large cities declined relatively quickly, for unknown reasons, leaving a less sophisticated village culture behind.[5]

Mahajanapadas (600 BCE—320 BCE)

Urban architecture

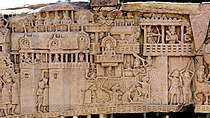

From the time of the Mahajanapadas (600 BCE—320 BCE), walled and moated cities with large gates and multi-storied buildings which consistently used arched windows and doors and made an intense use of wooden architecture, are important features of the architecture during this period.[6] The reliefs of Sanchi, dated to the 1st centuries BCE-CE, show cities such as Kushinagar or Rajagriha as spendid walled cities during the time of the Buddha (5th century BCE), as in the Royal cortege leaving Rajagriha or War over the Buddha's relics. These views of ancient Indian cities have been relied on for the understanding of ancient Indian urban architecture. Archaeologically, this period corresponds in part to the Northern Black Polished Ware culture.[7] Geopolitically, the Achaemenid Empire started to occupy the northwestern part of the subcontinent from around 518 BCE.[8][9]

Various types of individual housing of the time of the Buddha (c. 563/480 or c. 483/400 BCE), resembling huts with chaitya-decorated doors, are also described in the reliefs of Sanchi. Particularly, the Jetavana at Sravasti, shows the three favourite residences of the Buddha: the Gandhakuti, the Kosambakuti and the Karorikuti, with the throne of the Buddha in the front of each. The Jetavana garden was presented to the Buddha by the rich banker Anathapindika, who purchased it for as many gold pieces as would cover the surface of the ground. Hence, the foreground of the relief is shown covered with ancient Indian coins (karshapanas), just as it is in the similar relief at Bharhut.[10] Although the reliefs of Sanchi are dated to the 1st century BCE/CE, portraying scene taking place during the time of the Buddha, four centuries before, they are considered as an important indication of building traditions in these early times.[11]

Religious architecture

- Buddhist caves

During the time of the Buddha (c. 563/480 or c. 483/400 BCE), Buddhist monks were also in the habit of using natural caves, such as the Saptaparni Cave, southwest from Rajgir, Bihar.[12][13] Many believe it to be the site in which Buddha spent some time before his death,[14] and where the first Buddhist council was held after the Buddha died (paranirvana).[12][15][16] The Buddha himself had also used the Indrasala Cave for meditation, starting a tradition of using caves, natural or man-made, as religious retreats, that would last for over a millennium.[17]

- Monasteries

The first monasteries, such as the Jivakarama vihara in Rajgir, Bihar, were built from the time of the Buddha, in the 6th or 5th centuries BCE.[18][19][20] The initial Jivakarama monastery was formed of two long parallel and oblong halls, large dormitories where the monks could eat and sleep, in conformity with the original regulations of the samgha, without any private cells.[18] Other halls were then constructed, mostly long, oblong building as well, which remind of the construction of several of the Barabar caves.[18][21] The Buddha is said to have been treated once in the monastery, after having been injured by Devadatta.[18][22]

- Stupas

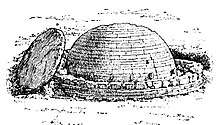

Religious buildings in the form of the Buddhist stupa, a dome shaped monument, started to be used in India as commemorative monuments associated with storing sacred relics of the Buddha.[23] The relics of the Buddha were spread between eight stupas, in Rajagriha, Vaishali, Kapilavastu, Allakappa, Ramagrama, Pava, Kushinagar, and Vethapida.[24] The Piprahwa stupa also seems to have been one of the first to be built.[24] Guard rails —consisting of posts, crossbars, and a coping— became a feature of safety surrounding a stupa.[6] The Buddha had left instructions about how to pay hommage to the stupas: "And whoever lays wreaths or puts sweet perfumes and colours there with a devout heart, will reap benefits for a long time".[25] This practice would lead to the decoration of the stupas with stone sculptures of flower garlands in the Classical period.[25]

Classical period (320 BCE-550 CE)

Monumental stone architecture

The next wave of building, relying on the first examples of true stone architecture, appears with the start of the Classical period (320 BCE-550 CE) and the rise of the Mauryan Empire. The capital city of Pataliputra was an urban marvel described by the Greek ambassador Megasthenes. Remains of monumental stone architecture with a strong Achaemenid and Greek influence can be seen through numerous artifacts recovered from Pataliputra, such as the Pataliputra capital. This cross-fertilization between different art streams converging on the subcontinent produced new forms that, while retaining the essence of the past, succeeded in the integrating selected elements of the new influences.

The Indian emperor Ashoka (rule: 273—232 BCE) established the Pillars of Ashoka throughout his realm, generally next to Buddhist stupas. According to Buddhist tradition, Ashoka recovered the relics of the Buddha from the earlier stupas (except from the Ramagrama stupa), and erected 84.000 stupas to distribute the relics across India. In effect, many stupas are thought to date originally from the time of Ashoka, such as Sanchi or Kesariya, where he also erected pillars with his inscriptions, and possibly Bharhut, Amaravati or Dharmarajika in Gandhara.[24]

Ashoka also built the initial Mahabodhi temple in Bodh Gaya around the Bodhi tree, including masterpieces such as the Diamond throne ("Vajrasana"). He is also said to have established a chain of hospitals throughout the Mauryan empire by 230 BCE.[26] One of the edicts of Ashoka reads: "Everywhere King Piyadasi (Ashoka) erected two kinds of hospitals, hospitals for people and hospitals for animals. Where there were no healing herbs for people and animals, he ordered that they be bought and planted."[27] Indian art and culture has absorbed extraneous impacts by varying degrees and is much richer for this exposure.

Fortified cities with stūpas, viharas, and temples were constructed during the Maurya empire (c. 321–185 BCE).[6] Architectural creations of the Mauryan period, such as the city of Pataliputra, the Pillars of Ashoka, are outstanding in their achievements, and often compare favourably with the rest of the world at that time. Commenting on Mauryan sculpture, John Marshall once wrote about the "extraordinary precision and accuracy which characterizes all Mauryan works, and which has never, we venture to say, been surpassed even by the finest workmanship on Athenian buildings".[28][29]

Ruins of pillared hall at the Kumrahar site at Pataliputra.

Ruins of pillared hall at the Kumrahar site at Pataliputra. Mauryan polished stone pillar from Pataliputra.

Mauryan polished stone pillar from Pataliputra.

Rock-cut caves

Around the same time rock-cut architecture began to develop, starting with the already highly sophisticated and state-sponsored Barabar caves in Bihar, personally dedicated by Ashoka circa 250 BCE.[6] These artificial caves exhibit an amazing level of technical proficiency, the extremely hard granite rock being cut in geometrical fashion and polished to a mirror-like finish.[17]

Probably owing to the 2nd century BCE fall of the Mauryan Empire and the subsequent persecutions of Buddhism under Pushyamitra Sunga, it is thought that many Buddhists relocated to the Deccan under the protection of the Andhra dynasty, thus shifting the cave-building effort to western India: an enormous effort at creating religious caves (usually Buddhist or Jain) continued there until the 2nd century CE, culminating with the Karla caves or the Pandavleni caves.[17] These caves generally followed an apsidal plan with a stupa in the back fot the chaityas, and a rectangular plan with surrounding cells for the viharas.[17] Numerous donors provided the funds for the building of these caves and left donatory inscriptions, including laity, members of the clergy, government officials, and even foreigners such as Yavanas (Greeks) representing about 8% of all inscriptions.[31]

The construction of caves would wane after the 2nd century CE, possibly due to the rise of Mahayana Buddhism and the associated intense architectural and artistic production in Gandhara and Amaravati.[17] The building of rock-cut caves would revive briefly in the 5th century CE, with the magnificent achievements of Ajanta and Ellora, before finally subsiding as Hinduism replaced Buddhism in the sub-continent, and stand-alone temples became more prevalent.[6][17]

Rock-cut architecture also developed with the apparition of stepwells in India, dating from 200–400 CE.[32] Subsequently, the construction of wells at Dhank (550–625 CE) and stepped ponds at Bhinmal (850–950 CE) took place.[32]

- Jain cave monastery in Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves (2nd century BCE).

The Great Chaitya in the Karla Caves, Maharashtra, India, c. 120 CE.

The Great Chaitya in the Karla Caves, Maharashtra, India, c. 120 CE..jpg) Gautamiputra vihara at Pandavleni Caves built in the 2nd century CE by the Satavahana dynasty.

Gautamiputra vihara at Pandavleni Caves built in the 2nd century CE by the Satavahana dynasty. The Ajanta Caves are 30 rock-cut Buddhist cave monument built under the Vakatakas, c. 5th century CE.

The Ajanta Caves are 30 rock-cut Buddhist cave monument built under the Vakatakas, c. 5th century CE.

Decorated stupas

Stupas were soon to be richly decorated with sculptural reliefs, following the first attempts at Sanchi Stupa No.2 (125 BCE). Full-fledged sculptural decorations and scenes of the life of the Buddha would soon follow at Bharhut (115 BCE), Bodh Gaya (60 BCE), Mathura (125-60 BCE), again at Sanchi for the elevation of the toranas (1st century BCE/CE) and then Amaravati (1st-2nd century CE).[33] The decorative embellishment of stupas also had a considerable development in the northwest in the area of Gandhara, with decorated stupas such as the Butkara Stupa ("monumentalized" with Hellenistic decorative elements from the 2nd century BCE)[34] or the Loriyan Tangai stupas (2nd century CE). Stupa architecture was adopted in Southeast and East Asia, where it became prominent as a Buddhist monument used for enshrining sacred relics.[23] The Indian gateway arches, the torana, reached East Asia with the spread of Buddhism.[35] Some scholars hold that torii derives from the torana gates at the Buddhist historic site of Sanchi (3rd century BCE – 11th century CE).[36]

Sanchi Stupa No.2, the earliest known stupa with important displays of decorative reliefs, circa 125 BCE.[37]

Sanchi Stupa No.2, the earliest known stupa with important displays of decorative reliefs, circa 125 BCE.[37]

Stand-alone temples

Temples —built on elliptical, circular, quadrilateral, or apsidal plans— were initially constructed using brick and timber.[6] Some temples of timber with wattle-and-daub may have preceded them, but none remain to this day.[40]

- Circular temples

Some of the earliest free-standing temples may have been of a circular type, as the Bairat Temple in Bairat, Rajasthan, formed of a central stupa surrounded by a circular colonnade and an enclosing wall.[40] It was built during the time of Ashoka, and near it were found two of Ashoka's Minor Rock Edicts.[40] Ashoka also built the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya circa 250 BCE, also a circular structure, in order to protect the Bodhi tree under which the Buddha had found enlightenment. Representations of this early temple structure are found on a 100 BCE relief sculpted on the railing of the stupa at Bhārhut, as well as in Sanchi.[41] From that period the Diamond throne remains, an almost intact slab of sandstone decorated with reliefs, which Ashoka had established at the foot of the Bodhi tree.[42][43] These circular-type temples were also found in later rock-hewn caves such as Tulja Caves or Guntupalli.[40]

Remains of the circular Bairat Temple, circa 250 BCE. A stupa was located in the center.

Remains of the circular Bairat Temple, circa 250 BCE. A stupa was located in the center. Relief of a circular temple, Bharhut, circa 100 BCE.

Relief of a circular temple, Bharhut, circa 100 BCE.

- Apsidal temples

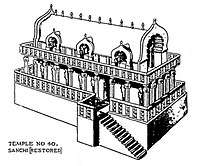

Another early free-standing temple in India, this time apsidal in shape, appears to be Temple 40 at Sanchi, which is also dated to the 3rd century BCE.[46] It was an apsidal temple built of timber on top of a high rectangular stone platform, 26.52x14x3.35 metres, with two flights of stairs to the east and the west. The temple was burnt down sometime in the 2nd century BCE.[47][48] This type of apsidal structure was also adopted for most of the cave temple (Chaitya-grihas), as in the 3rd century BCE Barabar Caves and most caves thereafter, with side, and then frontal, entrances.[40] A freestanding apsidal temple remains to this day, although in a modified form, in the Trivikrama Temple in Ter, Maharashtra.[49]

Trivikrama Temple at Ter: an early Buddhist apsidal temple, in front of which was later added an Hindu square mandapa.

Trivikrama Temple at Ter: an early Buddhist apsidal temple, in front of which was later added an Hindu square mandapa. Chejarla apsidal temple, also later converted to Hinduism.

Chejarla apsidal temple, also later converted to Hinduism.

- Truncated pyramidal temples

It is thought that the temple in the shape of a truncated pyramid was derived from the design of the stepped stupas which had developed in Gandhara.[50] The Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya is one such example, adapting the Gandharan design of a succession of steps with niches containing Buddha images, alternating with Greco-Roman pillars, as seen in the stupas of Jaulian.[50] The structure is crowned by the shape of an hemispherical stupa topped by finials, forming a logical elongation of the stepped Gandharan stupas.[50]

Although the current structure of the Mahabdhodi Temple dates to the Gupta period (5th century CE), the "Plaque of Mahabhodi Temple", discovered in Kumrahar and dated to 150-200 CE based on its dated Kharoshthi inscriptions and combined finds of Huvishka coins, suggests that the pyramidal structure already existed in the 2nd century CE.[50] This is confirmed by archaeological excavations in Bodh Gaya.[50]

This truncated pyramid design also marked the evolution from the aniconic stupa dedicated to the cult of relics, to the iconic temple with multiple images of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas.[50] This design was very influential in the development of later Hindu temples.[51]

- Square prostyle temples

The Gupta Empire later also built Buddhist stand-alone temples (following the great cave temples of Indian rock-cut architecture), such as Temple 17 at Sanchi, dating to the early Gupta period (5th century CE). It consists of a flat roofed square sanctum with a portico and four pillars. From an architectural perspective, this is a tetrastyle prostyle temple of Classical appearance .[52] The interior and three sides of the exterior are plain and undecorated but the front and the pillars are elegantly carved,[52] not unlike the 2nd century rock-cut cave temples of the Nasik caves. Nalanda and Valabhi universities, housing thousands of teachers and students, flourished between the 4th–8th centuries.[53]

End of the Classical period

This period ends with the destructive invasions of the Alchon Huns in the 6th century CE. During the rule of the Hunnic king Mihirakula, over a thousand Buddhist monasteries throughout Gandhara are said to have been destroyed.[54] The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang, writing in 630 CE, explained that Mihirakula ordered the destruction of Buddhism and the expulsion of monks.[55] He reported that Buddhism had drastically declined, and that most of the monasteries were deserted and left in ruins.[56] The Buddhist art of Gandhara, in particular Greco-Buddhist art, becomes essentially extinct around that period. The invasions mark the beginning of the decline of Buddhism in India.

Although only spanning a few decades, the invasions had long-term effects on India, and in a sense brought an end to Classical India.[57] Soon after the invasions, the Gupta Empire, already weakened by these invasions and the rise of local rulers, ended as well.[58] Following the invasions, northern India was left in disarray, with numerous smaller Indian powers emerging after the crumbling of the Guptas.[59]

Early Middle Ages (550 CE—1200 CE)

South Indian temple architecture—visible as a distinct tradition during the 7th century CE.[60]

Māru-Gurjara temple architecture originated somewhere in the sixth century in and around areas of Rajasthan. Māru-Gurjara Architecture shows the deep understanding of structures and refined skills of Rajasthani craftsmen of the bygone era. Māru-Gurjara Architecture has two prominent styles Maha-Maru and Maru-Gurjara. According to M. A. Dhaky, Maha-Maru style developed primarily in Marudesa, Sapadalaksha, Surasena and parts of Uparamala whereas Maru-Gurjara originated in Medapata, Gurjaradesa-Arbuda, Gurjaradesa-Anarta and some areas of Gujarat.[61] Scholars such as George Michell, M.A. Dhaky, Michael W. Meister and U.S. Moorti believe that Māru-Gurjara Temple Architecture is entirely Western Indian architecture and is quite different from the North Indian Temple architecture.[62] There is a connecting link between Māru-Gurjara Architecture and Hoysala Temple Architecture. In both of these styles architecture is treated sculpturally.[63] Regional styles include Architecture of Karnataka, Kalinga architecture, Dravidian architecture, Western Chalukya architecture, and Badami Chalukya Architecture.

The South Indian temple consists essentially of a square-chambered sanctuary topped by a superstructure, tower, or spire and an attached pillared porch or hall (maṇḍapa or maṇṭapam), enclosed by a peristyle of cells within a rectangular court. The external walls of the temple are segmented by pilasters and carry niches housing sculpture. The superstructure or tower above the sanctuary is of the kūṭina type and consists of an arrangement of gradually receding stories in a pyramidal shape. Each story is delineated by a parapet of miniature shrines, square at the corners and rectangular with barrel-vault roofs at the centre.

North Indian temples showed increased elevation of the wall and elaborate spire by the 10th century.[64] Richly decorated temples—including the complex at Khajuraho—were constructed in Central India.[64] Indian traders brought Indian architecture to South east Asia through various trade routes.[65] Grandeur of construction, beautiful sculptures, delicate carvings, high domes, gopuras and extensive courtyards were the features of temple architecture in India. Examples include the Lingaraj Temple at Bhubaneshwar in Odisha, Sun Temple at Konark in Odisha, Brihadeeswarar Temple at Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu.

The rock-cut Shore Temple of the temples in Mahabalipuram, 700-728 CE.

The rock-cut Shore Temple of the temples in Mahabalipuram, 700-728 CE. The Kandariya Mahadeva Temple at the Khajuraho Temple Complex in the shikhara style architecture, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Kandariya Mahadeva Temple at the Khajuraho Temple Complex in the shikhara style architecture, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The ruins of Mahavihara at Nalanda.

The ruins of Mahavihara at Nalanda..jpg)

Galaganatha Temple at Pattadakal complex is an example of Badami Chalukya architecture.

Galaganatha Temple at Pattadakal complex is an example of Badami Chalukya architecture..jpg) Martand Sun Temple Central shrine, dedicated to the deity Surya.

Martand Sun Temple Central shrine, dedicated to the deity Surya.

The granite tower of Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur was completed in 1010 CE by Raja Raja Chola I.

The granite tower of Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur was completed in 1010 CE by Raja Raja Chola I.

Late Middle Ages (1100 CE—1526 CE)

Vijayanagara Architecture of the period (1336 – 1565 CE) was a notable building style evolved by the Vijayanagar empire that ruled most of South India from their capital at Vijayanagara on the banks of the Tungabhadra River in present-day Karnataka.[67] The architecture of the temples built during the reign of the Vijayanagara empire had elements of political authority.[68] This resulted in the creation of a distinctive imperial style of architecture which featured prominently not only in temples but also in administrative structures across the deccan.[69] The Vijayanagara style is a combination of the Chalukya, Hoysala, Pandya and Chola styles which evolved earlier in the centuries when these empires ruled and is characterised by a return to the simplistic and serene art of the past.[70]

Hoysala architecture is the distinctive building style developed under the rule of the Hoysala Empire in the region historically known as Karnata, today's Karnataka, India, between the 11th and the 14th centuries.[71] Large and small temples built during this era remain as examples of the Hoysala architectural style, including the Chennakesava Temple at Belur, the Hoysaleswara Temple at Halebidu, and the Kesava Temple at Somanathapura. Other examples of fine Hoysala craftmanship are the temples at Belavadi, Amrithapura, and Nuggehalli. Study of the Hoysala architectural style has revealed a negligible Indo-Aryan influence while the impact of Southern Indian style is more distinct.[72] A feature of Hoysala temple architecture is its attention to detail and skilled craftsmanship. The temples of Belur and Halebidu are proposed UNESCO world heritage sites.[73] About a 100 Hoysala temples survive today.[74]

Konark Sun Temple at Konark, Orissa, built by Emperor Narasimhadeva I (1238–1264 CE) of the Eastern Ganga dynasty, it is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Konark Sun Temple at Konark, Orissa, built by Emperor Narasimhadeva I (1238–1264 CE) of the Eastern Ganga dynasty, it is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins.

Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins._(14465165685).jpg) Chennakesava Temple is a model example of the Hoysala architecture.

Chennakesava Temple is a model example of the Hoysala architecture. Elephant balustrades in the Bucesvara temple.

Elephant balustrades in the Bucesvara temple.- Stellate plan of the shrine in Chennakeshava Temple, Aralaguppe.

Kesava temple at the Chennakeshava Complex in Belur has been an active temple since its founding.

Kesava temple at the Chennakeshava Complex in Belur has been an active temple since its founding. Vijayanagara marketplace at Hampi, along with the sacred tank located on the side of Krishna temple.

Vijayanagara marketplace at Hampi, along with the sacred tank located on the side of Krishna temple. Stone temple car in Vitthala Temple at Hampi.

Stone temple car in Vitthala Temple at Hampi.- Virupaksha temple, Raya Gopura (main tower over entrance gate) at Hampi.

Early Modern period (1500 CE—1947 CE)

Rajput Architecture

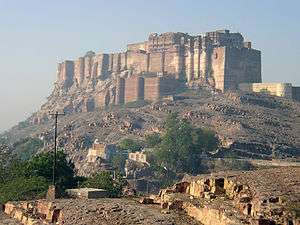

The Mughal architecture and painting influenced indigenous Rajput styles of art and architecture.[75] Rajput Architecture represents different types of buildings, which may broadly be classed either as secular or religious. The secular buildings are of various scales. These include temples, forts, stepwells, gardens, and palaces. The forts were specially built for defense and military purposes due to the Islamic invasions.

Built during the course of the 15th century by Rana Kumbha, the walls of the fort of Kumbhalgarh extend over 38 km, claimed to be the second-longest continuous wall after the Great Wall of China.

Built during the course of the 15th century by Rana Kumbha, the walls of the fort of Kumbhalgarh extend over 38 km, claimed to be the second-longest continuous wall after the Great Wall of China. Vijay Stambha is an imposing victory monument located within Chittorgarh fort.

Vijay Stambha is an imposing victory monument located within Chittorgarh fort..jpg)

City Palace was constructed by Udai Singh II after shifting his capital to Udaipur due to Muslim invasion.

City Palace was constructed by Udai Singh II after shifting his capital to Udaipur due to Muslim invasion. Chandramahal in City Palace, Jaipur, built by Kachwaha Rajputs.

Chandramahal in City Palace, Jaipur, built by Kachwaha Rajputs.

Ranakpur Jain temple was built in the 15th century with the support of the Rajput state of Mewar.

Ranakpur Jain temple was built in the 15th century with the support of the Rajput state of Mewar. Chaturbhuj Temple dedicated to Vishnu was the tallest structure in the Indian subcontinent from 1558 CE to 1970 CE.

Chaturbhuj Temple dedicated to Vishnu was the tallest structure in the Indian subcontinent from 1558 CE to 1970 CE. Umaid Bhawan Palace in Rajasthan, one of the world's largest private residences, built by Maharaja Umaid Singh, the ruler of Jodhpur State.

Umaid Bhawan Palace in Rajasthan, one of the world's largest private residences, built by Maharaja Umaid Singh, the ruler of Jodhpur State. Laxmi Niwas Palace, was built in Indo-Saracenic style, was commissioned by the Maharaja of Bikaner State.

Laxmi Niwas Palace, was built in Indo-Saracenic style, was commissioned by the Maharaja of Bikaner State.

Buddhist Architecture

Buddhist architecture developed in the Indian subcontinent. Three types of structures are associated with the religious architecture of early Buddhism: monasteries (viharas), places to venerate relics (stupas), and shrines or prayer halls (chaityas, also called chaitya grihas), which later came to be called temples in some places. The initial function of a stupa was the veneration and safe-guarding of the relics of Gautama Buddha. The earliest surviving example of a stupa is in Sanchi (Madhya Pradesh). In accordance with changes in religious practice, stupas were gradually incorporated into chaitya-grihas (prayer halls). These are exemplified by the complexes of the Ajanta Caves and the Ellora Caves (Maharashtra). The Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya in Bihar is another well-known example. The Pagoda is an evolution of the Indian stupa.

.jpg) Tawang Monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, was built in the 1600s, is the largest monastery in India and second largest in the world after the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet.

Tawang Monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, was built in the 1600s, is the largest monastery in India and second largest in the world after the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet. Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim was built under the direction of Changchub Dorje, 12th Karmapa Lama in the mid-1700s.[76]

Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim was built under the direction of Changchub Dorje, 12th Karmapa Lama in the mid-1700s.[76]

Indo-Islamic Architecture

The earliest examples of Indo-Islamic Architecture are the buildings constructed by the Delhi Sultanates, most famously the Qutb Minar complex, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993. The complex consists of Qutb Minar, a brick minaret commissioned by Qutub-ud-Din Aibak, as well as other monuments built by successive Delhi Sultans.[77]

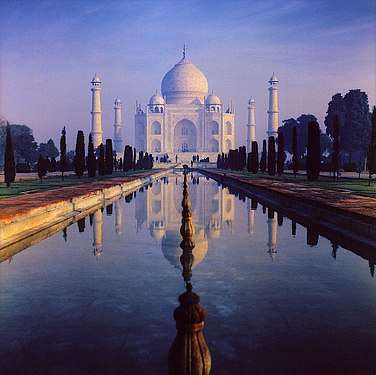

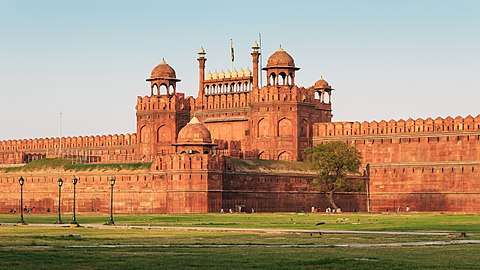

The most famous Indo-Islamic style is Mughal architecture. Its most prominent examples are the series of imperial mausolea, which started with the pivotal Tomb of Humayun, but is best known for the Taj Mahal. The Red Fort at Agra (1565–74) and the walled city of Fatehpur Sikri (1569–74) are among the architectural achievements of this time—as is the Taj Mahal, built as a tomb for Queen Mumtaz Mahal by Shah Jahan (1628–58).[78] Employing the double dome, the recessed archway, the depiction of any animal or human—an essential part of the Indian tradition—was forbidden in places of worship under Islam. The Taj Mahal does contain tilework of plant ornaments.[1] The architecture during the Mughal Period, with its rulers being of Turco-Mongol origin, has shown a notable blend of Indian style combined with the Islamic. Taj Mahal in Agra, India is one of the wonders of the world.

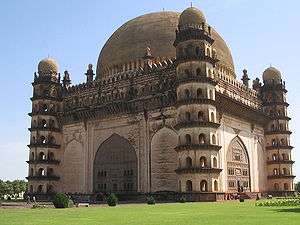

The Deccan sultanates in the Southern regions of the Indian subcontinent developed the Indo-Islamic Deccani architectural styles like Charminar, Mecca Masjid, Qutb Shahi Tombs and Gol Gumbaz.[79]

Within the Indian subcontinent, the Bengal region developed a distinct regional style under the independent Bengal Sultanate. It incorporated influences from Persia, Byzantium and North India,[80] which were with blended indigenous Bengali elements, such as curved roofs, corner towers and complex terracotta ornamentation. One feature in the sultanate was the relative absence of minarets.[81] Many small and medium-sized medieval mosques, with multiple domes and artistic niche mihrabs, were constructed throughout the region.[81] The grand mosque of Bengal was the 14th century Adina Mosque, the largest mosque in the Indian subcontinent. Built of stone demolished from temples, it featured a monumental ribbed barrel vault over the central nave, the first such giant vault used anywhere in the subcontinent. The mosque was modeled on the imperial Sasanian style of Persia.[82] The Sultanate style flourished between the 14th and 16th centuries. A provincial style influenced by North India evolved in Mughal Bengal during the 17th and 18th centuries. The Mughals also copied the Bengali do-chala roof tradition for mausoleums in North India.[83]

Qutub Minar built at the start of the Delhi Sultanate, a massive statement of conquest.

Qutub Minar built at the start of the Delhi Sultanate, a massive statement of conquest.

Gol Gumbaz built by the Bijapur Sultanate in Deccani style, the world's 2nd largest pre-modern.[note 1]

Gol Gumbaz built by the Bijapur Sultanate in Deccani style, the world's 2nd largest pre-modern.[note 1] Charminar at Old City in Hyderabad, legend has it that it was built by Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah to commemorate the end of a plague that ravaged the city.

Charminar at Old City in Hyderabad, legend has it that it was built by Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah to commemorate the end of a plague that ravaged the city.- Adina Mosque, the largest mosque of Bengali Muslim architecture.

Maratha Architecture

The Marathas ruled over much of the Indian subcontinent from the mid-17th to the early 19th centuries.[85] Their religious activity took full shape and soon the skylines of Maharashtrian towns were dominated by rising temple spires. Old forms returned with this 'renewal' of Hindu architecture, infused by the Sultanate and later the Mughal traditions. The architecture of Maratha period was planned with courtyards suited to tropical climates. The Maratha Architecture is known for its simplicity, visible logic and austere aesthetic, made rich by beautiful detailing, rhythm, and repetition. The aisles and arcades, punctured by delicate niches, doors, and windows create space in which the articulation of open, semi-open and covered areas is effortless and enchanting. The materials used during those times for construction were –

- Thin bricks

- Lime mortar

- Lime plaster

- Wooden columns

- Stone bases

- Basalt stone flooring

- Brick pavements

Maharashtra is famous for its caves and rock-cut architectures. It is said that the varieties found in Maharashtra are wider than the caves and rock-cut architectures found in the rock-cut areas of Egypt, Assyria, Persia, and Greece. The Buddhist monks first started these caves in the 2nd century BC, in search of serene and peaceful environment for meditation, and they found these caves on the hillsides.

Sikh Architecture

Sikh Architecture is a style of architecture that is characterized by values of progressiveness, exquisite intricacy, austere beauty and logical flowing lines. Due to its progressive style, it is constantly evolving into many newly developing branches with new contemporary styles. Although Sikh architecture was initially developed within Sikhism its style has been used in many non-religious buildings due to its beauty. 300 years ago, Sikh architecture was distinguished for its many curves and straight lines; Shri Keshgarh Sahib and the Sri Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) are prime examples.

European colonial architecture

As with the Mughals, under European colonial rule, architecture became an emblem of power, designed to endorse the occupying power. Numerous European countries invaded India and created architectural styles reflective of their ancestral and adopted homes. The European colonizers created architecture that symbolized their mission of conquest, dedicated to the state or religion.[86]

The British, French, Dutch and the Portuguese were the main European powers that colonized parts of India.[87][88]

British Colonial Era: 1615 to 1947

The British arrived in 1615 and over the centuries, gradually overthrew the Maratha and Sikh empires and other small independent kingdoms. Britain was present in India for over three hundred years and their legacy still remains through some building and infrastructure that exist in their former colonies.[89] The major cities colonized during this period were Madras, Calcutta, Bombay, Delhi, Agra, Bankipore, Karachi, Nagpur, Bhopal and Hyderabad,[90][88] which saw the rise of Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture.

St Andrews Kirk, Madras is known for its colonial architecture. The building is circular in form and is sided by two rectangular sections one is the entrance porch. The entrance is lined with twelve colonnades and two British lions and motto of East India Company engraved on them. The interior holds sixteen columns and the dome is painted blue with decorated with gold stars.[91]

Black Town described in 1855 as "the minor streets, occupied by the natives are numerous, irregular and of various dimensions. Many of them are extremely narrow and ill-ventilated ... a hallow square, the rooms opening into a courtyard in the centre."[92]

Garden houses were originally used as weekend houses for recreational use by the upper class British. Nonetheless, the garden house became ideal a full-time dwelling, deserting the fort in the 19th Century.[93]

Calcutta – Madras and Calcutta were similarly bordered by water and division of Indian in the north and British in the south. An Englishwoman noted in 1750 "the banks of the river are as one may say absolutely studded with elegant mansions called here as at Madras, garden houses." Esplanade-row is fronts the fort with lined palaces.[94][95]

Indian villages in these areas consisted of clay and straw houses which later transformed into the metropolis of brick and stone.[96]

The Victoria Memorial in Calcutta is the most effective symbolism of British Empire, built as a monument in tribute to Queen Victoria’s reign. The plan of the building consists of one large central part covered with a larger dome. Colonnades separate the two chambers. Each corner holds a smaller dome and is floored with marble plinth. The memorial stands on 26 hectares of garden surrounded by reflective pools.[97]

Rashtrapati Bhavan is a residence in New Delhi built for the British Viceroy.

Rashtrapati Bhavan is a residence in New Delhi built for the British Viceroy. The Victoria Memorial in Kolkata illuminated at night.

The Victoria Memorial in Kolkata illuminated at night. The Gateway of India was a monument erected to commemorate the landing of King George V and Queen Mary.

The Gateway of India was a monument erected to commemorate the landing of King George V and Queen Mary.

Madras High Court buildings are a prime example of Indo-Saracenic architecture, designed by J W Brassington under the guidance of British architect Henry Irwin.

Madras High Court buildings are a prime example of Indo-Saracenic architecture, designed by J W Brassington under the guidance of British architect Henry Irwin..jpg) The Victoria Terminus (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus) is a historic railway station in Mumbai, 1878-88 CE.

The Victoria Terminus (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus) is a historic railway station in Mumbai, 1878-88 CE.

Republic of India (1947 CE—present)

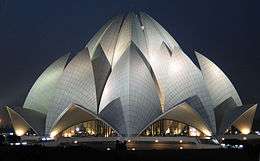

Lotus Temple in Delhi, completed in 1986 and one of the largest Bahá'í House of Worship in the world.

Lotus Temple in Delhi, completed in 1986 and one of the largest Bahá'í House of Worship in the world. Akshardham Temple in Delhi, completed in 2005 and one of the largest Hindu temples in the world.

Akshardham Temple in Delhi, completed in 2005 and one of the largest Hindu temples in the world..jpg) Golden Pagoda in Namsai, completed in 2010 and one of the notable Buddhist temples in India.

Golden Pagoda in Namsai, completed in 2010 and one of the notable Buddhist temples in India.

In recent times there has been a movement of population from rural areas to urban centres of industry, leading to price rise in property in various cities of India.[99] Urban housing in India balances space constrictions and is aimed to serve the working class.[100] Growing awareness of ecology has influenced architecture in India during modern times.[101]

Climate responsive architecture has long been a feature of India's architecture but has been losing its significance as of late.[102] Indian architecture reflects its various socio-cultural sensibilities which vary from region to region.[102] Certain areas are traditionally held to be belonging to women.[102] Villages in India have features such as courtyards, loggias, terraces and balconies.[100] Calico, chintz, and palampore—of Indian origin—highlight the assimilation of Indian textiles in global interior design.[103] Roshandans, which are skylights-cum-ventilators, are a common feature in Indian homes, especially in North India.[104][105]

Gallery

Dakshineswar Kali Temple is famous for its association with Ramakrishna.

Dakshineswar Kali Temple is famous for its association with Ramakrishna.

Dilwara Temples are famous for their use of marble and intricate marble carvings.

Dilwara Temples are famous for their use of marble and intricate marble carvings. Maha-Bodhi Mulagandhakuti Buddhist Temple at Sarnath.

Maha-Bodhi Mulagandhakuti Buddhist Temple at Sarnath.- Global Vipassana Pagoda is a Meditation Dome Hall with a capacity to seat around 8,000 Vipassana meditators, largest such meditation hall in the world, near Gorai, North-west of Mumbai, India.

Gurudwara Bangla Sahib is one of the most prominent Sikh gurdwara.

Gurudwara Bangla Sahib is one of the most prominent Sikh gurdwara.

- Makkah Masjid in Hyderabad is one of the largest and oldest mosque in South India.

Rang Ghar, built by Pramatta Singha in Ahom Kingdom's capital Rongpur, is one of the earliest pavilions of outdoor stadia in the Indian subcontinent.

Rang Ghar, built by Pramatta Singha in Ahom Kingdom's capital Rongpur, is one of the earliest pavilions of outdoor stadia in the Indian subcontinent.

See also

- Western Chalukya architecture

- Badami Chalukya architecture

- Hoysala architecture

- Vijayanagara architecture

- Dravidian architecture

- Architecture of Karnataka

- Hindu temple architecture

- Hoysala architecture

- Badami cave temples

- Temples of North Karnataka

- Indian vernacular architecture

- Rajasthani architecture

- Hemadpanthi

- Jainism in North Karnataka

- List of Indian architects

- Kalinga Architecture

- Architecture of Kerala

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Architecture of India. |

Notes

- 1 2 3 See Raj Jadhav, pp. 7–13 in Modern Traditions: Contemporary Architecture in India.

- ↑ Takezawa, Suichi. "Stepwells -Cosmology of Subterranean Architecture as seen in Adalaj" (pdf). The Diverse Architectural World of The Indian Sub-Continent. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ↑ Rowland, 31-34, 32 quoted; Harle, 15-18

- 1 2 Livingstone & Beach, 19

- ↑ Rowland, 31-34, 33 quoted; Harle, 15-18

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chandra (2008)

- ↑ J.M. Kenoyer (2006), "Cultures and Societies of the Indus Tradition. In Historical Roots" in the Making of ‘the Aryan’, R. Thapar (ed.), pp. 21–49. New Delhi, National Book Trust.

- ↑ Roy, Kaushik (2015). Military Manpower, Armies and Warfare in South Asia. Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 9781317321279.

- ↑ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2016). A History of India. Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 9781317242123.

- ↑ John Marshall, A Guide to Sanchi, 1918 p.58ff (Public Domain text)

- ↑ Brown, Percy (1959). Indian Architecture (Buddhist And Hindu). pp. 3–5.

- 1 2 Paul Gwynne (30 May 2017). World Religions in Practice: A Comparative Introduction. Wiley. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-1-118-97228-1.

- ↑ Jules Barthélemy Saint-Hilaire (1914). The Buddha and His Religion. Trübner. pp. 376–377.

- ↑ Digha Nikaya 16, Maha-Parinibbana Sutta, Last Days of the Buddha, Buddhist Publication Society

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain (1991). Lord Mahāvīra and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 66. ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8.

- ↑ Chakrabartia, Dilip K (1976). "Rājagriha: An early historic site in East India". World Archaeology. 7 (3): 261–268. doi:10.1080/00438243.1976.9979639.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, p.97-99

- 1 2 3 4 Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. pp. 48–49. ISBN 9780984404308.

- ↑ "The rubble-built building complex of Jivakamravana at Rajgir probably represents one of the earliest monasteries of India dating from the Buddha's time." in Mishra, Phanikanta; Mishra, Vijayakanta (1995). Researches in Indian archaeology, art, architecture, culture and religion: Vijayakanta Mishra commemoration volume. Sundeep Prakashan. p. 178. ISBN 9788185067803.

- ↑ Tadgell, Christopher (2015). The East: Buddhists, Hindus and the Sons of Heaven. Routledge. p. 498. ISBN 9781136753831.

- ↑ Handa, O. C.; Hāṇḍā, Omacanda (1994). Buddhist Art & Antiquities of Himachal Pradesh, Upto 8th Century A.D. Indus Publishing. p. 162. ISBN 9788185182995.

- ↑ Monuments of Bihar. Department of Art, Culture & Youth, Government of Bihar. 2011. pp. Jivakarama vihara entry.

- 1 2 Encyclopædia Britannica (2008), Pagoda.

- 1 2 3 Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, p.140-174

- 1 2 Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, p.143

- ↑ Piercey & Scarborough (2008)

- ↑ See Stanley Finger (2001), Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations Into Brain Function, Oxford University Press, p. 12, ISBN 0-19-514694-8.

- ↑ The Early History of India by Vincent A. Smith

- ↑ Annual report 1906-07 p.89

- ↑ Ashoka in Ancient India by Nayanjot Lahiri p. 231

- ↑ Buddhist architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, p.98-99

- 1 2 Livingston & Beach, xxiii

- 1 2 3 Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, p.149-150

- ↑ "De l'Indus a l'Oxus: archaeologie de l'Asie Centrale", Pierfrancesco Callieri, p212: "The diffusion, from the second century BCE, of Hellenistic influences in the architecture of Swat is also attested by the archaeological searches at the sanctuary of Butkara I, which saw its stupa "monumentalized" at that exact time by basal elements and decorative alcoves derived from Hellenistic architecture".

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica (2008), torii

- ↑ Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System (2001), torii.

- ↑ Didactic Narration: Jataka Iconography in Dunhuang with a Catalogue of Jataka Representations in China, Alexander Peter Bell, LIT Verlag Münster, 2000 p.15ff

- ↑ World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India, Volume 1 p.50 by Alī Jāvīd, Tabassum Javeed, Algora Publishing, New York

- ↑ Luders, Heinrich (1963). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol.2 Pt.2 Bharhut Inscriptions. p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Le Huu Phuoc, 2009, p.233-237

- ↑ "Sowing the Seeds of the Lotus: A Journey to the Great Pilgrimage Sites of Buddhism, Part I" by John C. Huntington. Orientations, November 1985 pg 61

- ↑ Buddhist Architecture, Huu Phuoc Le, Grafikol, 2010 p.240

- ↑ A Global History of Architecture, Francis D. K. Ching, Mark M. Jarzombek, Vikramaditya Prakash, John Wiley & Sons, 2017 p.570ff

- ↑ Hardy, Adam (1995). Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation : the Karṇāṭa Drāviḍa Tradition, 7th to 13th Centuries. Abhinav Publications. p. 39. ISBN 9788170173120.

- ↑ Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 238. ISBN 9780984404308.

- 1 2 Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, p.147

- ↑ Abram, David; (Firm), Rough Guides (2003). The Rough Guide to India. Rough Guides. ISBN 9781843530893.

- ↑ Marshall, John (1955). Guide to Sanchi.

- ↑ Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 237. ISBN 9780984404308.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Le Huu Phuoc, Buddhist Architecture, pp.238-248

- ↑ Le Huu Phuoc, Buddhist Architecture, p.234

- 1 2 3 2500 Years of Buddhism by P.V. Bapat, p.283

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica (2008), education, history of.

- ↑ Behrendt, Kurt A. (2004). Handbuch der Orientalistik. BRILL. ISBN 9789004135956.

- ↑ Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks by Jason Neelis p.168

- ↑ The Spread of Buddhism by Ann Heirman,Stephan Peter Bumbacher p.60 sq

- ↑ The First Spring: The Golden Age of India by Abraham Eraly p.48 sq

- ↑ Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen p.221

- ↑ A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India p.174

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica (2008), South Indian temple architecture.

- ↑ The sculpture of early medieval Rajasthan By Cynthia Packert Atherton

- ↑ Beginnings of Medieval Idiom c. A.D. 900–1000 by George Michell

- ↑ The legacy of G.S. Ghurye: a centennial festschrift By Govind Sadashiv Ghurye, A. R. Momin, p-205

- 1 2 Encyclopædia Britannica (2008), North Indian temple architecture.

- ↑ Moffett et al., 75

- ↑ K. D. Bajpai (2006). History of Gopāchala. Bharatiya Jnanpith. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-263-1155-2.

- ↑ See Percy Brown in Sūryanātha Kāmat's A concise history of Karnataka: from pre-historic times to the present, p. 132.

- ↑ See Carla Sinopoli, Echoes of Empire: Vijayanagara and Historical Memory, Vijayanagara as Historical Memory, p. 26.

- ↑ See Carla Sinopoli, The Political Economy of Craft Production: Crafting Empire in South India, C. 1350–1650, p. 209.

- ↑ See Percy Brown in Sūryanātha Kāmat's A concise history of Karnataka: from pre-historic times to the present, p. 182.

- ↑ MSN Encarta (2008), Hoysala_Dynasty. Archived 2009-10-31.

- ↑ See Percy Brown in Sūryanātha Kāmat's A concise history of Karnataka: from pre-historic times to the present, p. 134.

- ↑ The Hindu (2004), Belur for World Heritage Status.

- ↑ Foekema, 16

- ↑ Kossak, Steven; Watts, Edith Whitney (2001). The Art of South and Southeast Asia: A Resource for Educators. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870999925.

- ↑ Achary Tsultsem Gyatso; Mullard, Saul & Tsewang Paljor (Transl.): A Short Biography of Four Tibetan Lamas and Their Activities in Sikkim, in: Bulletin of Tibetology Nr. 49, 2/2005, p. 57.

- ↑ "Qutb Minar and its Monuments, Delhi". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica (2008), Mughal architecture.

- ↑ Michell, George & Mark Zebrowski. Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999, ISBN 0-521-56321-6, p.14 & pp.77–80.

- ↑ "Architecture - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- 1 2 Hasan, Perween (2007). Sultans and Mosques:The Early Muslim Architecture of Bangladesh. United Kingdom: I.B. Tauris. p. 23–27. ISBN 1-84511-381-0.

- ↑ "BENGAL – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ↑ Petersen, Andrew (2002). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. p. 33–35. ISBN 1-134-61366-0.

- ↑ Mukherjee, Anisha (3 June 2018). "Whose fort is it anyway". The Indian Express.

- ↑ An Advanced History of Modern India By Sailendra Nath Sen, p.16

- ↑ Thapar 2004, p. 122.

- ↑ Nilsson 1968, p. 9.

- 1 2 "(Brief) History of European – Asian trade". European Exploration. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ↑ Jaffar 1936, p. 230.

- ↑ Tadgell 1990, p. 14.

- ↑ Thapar 2004, p. 125.

- ↑ Evenson 1989, p. 2.

- ↑ Evenson 1989, p. 6.

- ↑ Evenson 1989, p. 20.

- ↑ Dutta, Arindam (29 March 2010). "Representing Calcutta: Modernity, Nationalism and the Colonial Uncanny". Journal of Architectural Education. 63 (2): 167–169. doi:10.1111/j.1531-314X.2010.01082.x.

- ↑ Nilsson 1968, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Thapar 2004, p. 129.

- ↑ Bhagwat, Ramu (19 December 2001). "Ambedkar memorial set up at Deekshabhoomi". Times of India. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ See Raj Jadhav, p. 11 in Modern Traditions: Contemporary Architecture in India.

- 1 2 Gast, 77

- ↑ Gast, 119

- 1 2 3 See Raj Jadhav, 13 in Modern Traditions: Contemporary Architecture in India.

- ↑ Savage 2008

- ↑ Thomas George Percival Spear; Margaret Spear, India remembered, Orient Longman, 1981, ISBN 978-0-86131-265-8,

... The bungalow was a typical north Indian one, with a large central room lit only by skylights (roshandans) and a number of others opening out from them ...

- ↑ Pavan K. Varma, Sondeep Shankar, Mansions at dusk: the havelis of old Delhi, Spantech Publishers, 1992, ISBN 978-81-85215-14-3,

... Thirdly, while obviating direct sunlight, it had to allow some light and air to enter through overhead roshandans ...

- ↑

References

- Foekema, Gerard (1996), A Complete Guide to Hoysaḷa Temples, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 81-7017-345-0.

- Gast, Klaus-Peter (2007), Modern Traditions: Contemporary Architecture in India, Birkhäuser, ISBN 978-3-7643-7754-0.

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Jaffar, S.M (1936). The Mughal Empire From Babar To Aurangzeb. Peshawar City: Muhammad Sadiq Khan. OU_1 60252.

- Keay, John, India, a History, 2000, HarperCollins, ISBN 0002557177

- Lach, Donald F. (1993), Asia in the Making of Europe (vol. 2), University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-46730-9.

- Livingston, Morna & Beach, Milo (2002), Steps to Water: The Ancient Stepwells of India, Princeton Architectural Press, ISBN 1-56898-324-7.

- Michell, George, (1977) The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to its Meaning and Forms, 1977, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-53230-1

- Nilsson, Sten (1968). European Architecture in India 1750 – 1850. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-08225-4.

- Rowland, Benjamin, The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, 1967 (3rd edn.), Pelican History of Art, Penguin, ISBN 0140561021

- Savage, George (2008), interior design, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Tadgell, Christopher (1990). The history of architecture in India : from the dawn of civilization to the end of the Raj. London: Architecture Design and Technology Press. ISBN 1-85454-350-4.

- Thapar, Bindia (2004). Introduction to Indian Architecture. Singapore: Periplus Editions. ISBN 0-7946-0011-5.

- Vastu-Silpa Kosha, Encyclopedia of Hindu Temple architecture and Vastu/S.K.Ramachandara Rao, Delhi, Devine Books, (Lala Murari Lal Chharia Oriental series) ISBN 978-93-81218-51-8 (Set)

- Chandra, Pramod (2008), South Asian arts, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Evenson, Norma (1989). The Indian Metropolis. New Haven and London: Yale University press. ISBN 0-300-04333-3.

- Mankekar, Kamla (2004). Temples of Goa. India: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of Ind. ISBN 978-81-2301161-5.

- Moffett, Marion; Fazio, Michael W.; Wodehouse Lawrence (2003), A World History of Architecture, McGraw-Hill Professional, ISBN 0-07-141751-6.

- Piercey, W. Douglas & Scarborough, Harold (2008), hospital, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (1996), "Mehrgarh", Oxford Companion to Archaeology edited by Brian Fagan, Oxford University Press.

- Rodda & Ubertini (2004), The Basis of Civilization-Water Science?, International Association of Hydrological Science, ISBN 1-901502-57-0.

- Sinopoli, Carla M. (2003), The Political Economy of Craft Production: Crafting Empire in South India, C. 1350–1650, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-82613-6.

- Sinopoli, Carla M. (2003), "Echoes of Empire: Vijayanagara and Historical Memory, Vijayanagara as Historical Memory", Archaeologies of memory edited by Ruth M. Van Dyke & Susan E. Alcock, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 0-631-23585-X.

- Singh, Vijay P. & Yadava, R. N. (2003), Water Resources System Operation: Proceedings of the International Conference on Water and Environment, Allied Publishers, ISBN 81-7764-548-X.

- Teresi, Dick (2002), Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science—from the Babylonians to the Maya, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-684-83718-8.

Further reading

- Havell, E.B. (1913). Indian Architecture, its psychology, structure, and history from the first Muhammadan invasion to the present day. J. Murray, London.

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. (1914). Viśvakarmā ; examples of Indian architecture, sculpture, painting, handicraft. London.

- Havell, E. B. (1915). The Ancient and Medieval Architecture of India: a study of Indo-Aryan civilisation. John Murray, London.

- Fletcher, Banister; Cruickshank, Dan, Sir Banister Fletcher's a History of Architecture, Architectural Press, 20th edition, 1996 (first published 1896). ISBN 0-7506-2267-9. Cf. Part Four, Chapter 26.

External links

- ↑ After the Byzantine Hagia Sophia.

.jpg)