Booker T. Washington State Park (West Virginia)

| Booker T. Washington State Park | |

| Former West Virginia State Park | |

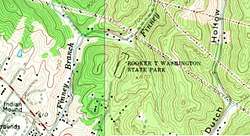

A topographic map from 1958 showing the location of Booker T. Washington State Park. | |

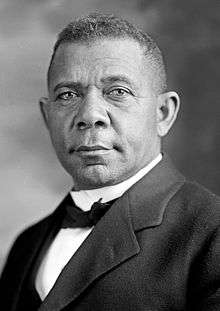

| Name origin: Booker T. Washington | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| State | West Virginia |

| County | Kanawha |

| City | Institute |

| Elevation | 732 ft (223 m) [1] |

| Coordinates | 38°22′55″N 81°44′53″W / 38.38194°N 81.74806°W [1] |

| Area | 7.43 acres (3 ha) [2] |

| Established | 1949 [3][4] |

| - Opened | 1949 [3][4] |

| - Closed | By 1959 [lower-alpha 1] |

| Owner | West Virginia Conservation Commission Division of State Parks [6][8][9] |

| Commons category | Booker T. Washington State Park (West Virginia) |

Location of Booker T. Washington State Park in West Virginia  Booker T. Washington State Park (West Virginia) (the US) | |

Booker T. Washington State Park is a former state park near the community of Institute in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The park was operated by the West Virginia Conservation Commission, Division of State Parks, from 1949 until the late 1950s.

The park was a day-use picnic area located on 7.43 acres (3 ha) of secondary forest outside Institute, approximately 0.86 miles (1.4 km) east of the West Virginia State College (now University) campus. The park was integrated shortly after the Brown v. Board of Education decision by the United States Supreme Court in May 1954.

The land and the vicinity of this park were once part of a dense concentration of Late Adena Native American mounds and earthworks along the Kanawha River, including the nearby Shawnee Reservation Mound. In the 18th century, the area became a part of a large land tract owned by George Washington. In 1853 Samuel I. Cabell purchased 967 acres (391 ha) of the valley. He and his wife Mary Barnes Cabell (a freedwoman) operated a plantation near the park's location, and following the American Civil War his children and the plantation's freed slaves settled the community of Piney Grove. Under the provisions of the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1890, the West Virginia Legislature established the West Virginia Colored Institute for the education of African Americans in 1891. The institute opened at Piney Grove in 1892, and the town's name was changed to Institute. In 1949 the West Virginia Conservation Commission, Division of State Parks, opened Booker T. Washington State Park, which was named for African American educator and West Virginia native Booker T. Washington. Following the park's integration in 1954, it remained open as a day-use picnic area until the late 1950s. By 1959 Booker T. Washington State Park was no longer listed in that year's West Virginia Blue Book listing of state parks.

Geography and setting

Booker T. Washington State Park was just outside the unincorporated community of Institute, Kanawha County, West Virginia, approximately 0.86 miles (1.4 km) east of the West Virginia State College (now University) campus.[10][11][12] The Shawnee Reservation Mound, a Late Adena Native American mound within present-day Shawnee Regional Park in Institute, is located 0.70 miles (1 km) southwest of the former park site.[11][12][13]

The park was situated on 7.43 acres (3 ha) at an elevation of 732 feet (223 m)[1] on the northern edge of the Kanawha River valley. It was bound by forested hills to its west and east, the confluence of Finney Branch and an unnamed stream in a hollow to its north, and the northern end of Pinewood Drive to its south.[10][11][12] Finney Branch is a tributary stream of the Kanawha River, which flows 1.22 miles (2 km) southwest of the park's location.[11][14] Dutch Hollow, formed by a Finney Branch tributary, is approximately 0.59 miles (1 km) east of the park's location and is the site of the Dutch Hollow Wine Cellars, presently located within Dunbar's Wine Cellar Park.[10][15][16] The former park land is covered in secondary forest consisting of tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), several species of oak (Quercus), American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), several species of pine (Pinus), and other deciduous species.[4]

Background

Area history

The 10-mile (16 km) section of the Kanawha River valley between present-day Charleston and St. Albans was once the site of a dense concentration of Late Adena Native American mounds and earthworks, including Institute's Shawnee Reservation Mound.[13][17] The Shawnee Reservation Mound is one of only three mounds that remain from this original complex of mounds and earthworks.[13]

This region of the Kanawha River valley was granted to George Washington, recently returned from fighting in the French and Indian War, following Virginia Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie's Proclamation of 1754.[18][19] The Proclamation of 1754 encouraged enlistment for the Monongahela expedition in exchange for a reward of land from a 200,000-acre (80,937 ha) reservation in western Virginia.[19] Between 1772 and 1774, Washington claimed four large land tracts in the Kanawha River valley totaling 23,216 acres (9,395 ha).[19] Washington leased the four tracts to James Welch in 1797, and following Welch's death the tracts reverted to Washington's estate.[19] These tracts were divided and sold into the 19th century by Washington's heirs.[18][19]

In Dutch Hollow, to the east of the Cabell property and the state park land, a vineyard and the Dutch Hollow Wine Cellars were established by Tom Friend around 1860 and operated for about three years.[20] The area's wine industry shuttered following the American Civil War possibly due to high labor costs, unreliable grape crops, and competition from out-of-state wineries.[20]

In 1853 Samuel I. Cabell purchased 967 acres (391 ha) encompassing the Kanawha River valley bottomlands between Sattes and the western area of present-day Dunbar.[18] Cabell, his wife Mary Barnes Cabell (a freedwoman), their family, and their slaves relocated to this property where Cabell operated a plantation.[18][21] In 1870 the Kanawha County Commissioners divided the former Cabell plantation land tract among his widow and his children, providing each with a strip of land extending between the hills to the north (where the park would later be located) and the Kanawha River bank to the south.[18] The present-day community of Institute is situated on land that was once part of Cabell's plantation.[18] Cabell's descendants and his former slaves remained in the vicinity of his plantation and settled a community known variously as Cabell Farm and Piney Grove.[18][21] A post office opened at Piney Grove in 1876, and Cabell's daughter Marina Cabell Hurt served as its postmaster.[18][22] Hurt is thought to have been the first African American female postmaster in the United States.[18] Piney Grove was renamed Cabell, then renamed Institute after the West Virginia Colored Institute.[18]

Under the provisions of the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1890, the West Virginia Legislature established the West Virginia Colored Institute for the education of African Americans in 1891.[21][23] The state purchased a 30-acre (12 ha) tract of land from Elijah and Marina Cabell Hurt, and commenced construction of the institute's campus.[18][21][24] The state gradually acquired adjacent lots until the campus consisted of approximately 80 acres (32 ha).[18]

The co-educational West Virginia Colored Institute opened in 1892 and added a military education program in 1899.[21] African American educator Booker T. Washington, a former Kanawha River valley resident from nearby Malden, frequently visited the institute's campus as a guest lecturer.[21] The institute's first president, Byrd Prillerman, was a friend of Washington, who had recommended Prillerman for the position in 1909.[21] The West Virginia Colored Institute gradually became the center of African American intellectual and academic life in West Virginia, and in 1915 it became known as the West Virginia Collegiate Institute to reflect its authority to grant college degrees as a post-secondary educational institution.[21] In 1929 the institution's name was changed to West Virginia State College.[21]

Development of state recreational facilities for African Americans

In response to the tremendous damage to West Virginia's natural environment from mineral and lumber exploitation, the state began the development of its state park system in the 1920s.[25][26] The state recognized the need to designate and protect lands worthy of conservation, and in 1925 the Legislature established the West Virginia State Forest, Park and Conservation Commission to assess the state's opportunities and needs for forests, parks, game preserves, and recreational areas.[25][26][27] The Legislature established the West Virginia Conservation Commission, Division of State Parks, in 1933 to manage the state's growing park system, and to leverage the resources and expertise of the New Deal-era programs for park development.[28] The park system continued to expand and consisted of approximately 30,000 acres (12,141 ha) by the mid-1930s.[26]

Despite West Virginia's growth in state parks, in both acreage and in number of locations, its state park system was not accessible by African Americans.[26] During the 1930s, West Virginia's historically black colleges (Bluefield State Teachers College, Storer College, and, primarily, West Virginia State College and its extension service) became the center of a movement to provide educational outdoor and recreational activities for West Virginia's African American youth.[29] The movement succeeded in taking advantage of available West Virginia Board of Control funding from the Works Progress Administration (WPA) when the Legislature established Camp Washington-Carver in 1937 near Clifftop in Fayette County.[26][30] The 583-acre (236 ha) African American 4-H camp was constructed by the WPA between 1939 and 1942 and was transferred from the West Virginia Board of Control to the West Virginia State College extension service, which offered instruction to African American children and adolescents in the subjects of agricultural education, soil conservation, home economics, and 4-H values.[31] West Virginia State named the 4-H camp complex after African American educators Booker T. Washington (a Kanawha River valley native) and George Washington Carver.[31] Its Great Chestnut Lodge is notable as being the largest log structure in West Virginia built entirely of chestnut.[32] Camp Washington-Carver was formally dedicated on July 26, 1942.[33]

Park establishment and operation

The West Virginia Conservation Commission, Division of State Parks, had expanded to 13 state parks by 1945;[34] however, West Virginia still restricted the access of African Americans to its state parks.[26] In 1940 the NAACP contacted the Division of State Parks and inquired about the accessibility of African Americans to West Virginia state parks.[26] The Division of State Parks responded by stating: "Negro citizens would feel ill at ease" at visiting state parks alongside white residents, and that the division was deliberating the construction of a state park for African Americans.[26]

By 1949 private citizens had donated 7.43 acres (3 ha) of deciduous forest land outside the largely African American community of Institute to the Division of State Parks for the construction of an African American recreational area.[4][26] On August 5, 1949, West Virginia Conservation Commission Director C. F. McClintic formally announced that a public day-use recreational area for African Americans was being developed in Institute, and would be named for Booker T. Washington.[4] At the time of the announcement, a water well was being drilled and picnic and sanitary facilities were being installed.[4] Present-day Pinewood Drive had already been constructed from West Virginia Route 25 to provide access to the park location, and a parking area for 15 cars had already been completed.[4] According to McClintic, the park's name was selected by the West Virginia Conservation Commission following consultation with West Virginia State College President Dr. John Warren Davis.[4]

Booker T. Washington State Park opened in 1949 as the only state park accessible to African Americans.[26][35][36] Following the park's completion, its limited facilities included the water well, ten picnic tables, fireplaces, toilets, and the parking area.[26] According to National Park Service (NPS) surveys of state parks in 1950 and 1955, Booker T. Washington State Park lacked swimming facilities, cabins, campsites, and refreshment stands.[8][9] Unlike other West Virginia state parks, Booker T. Washington also lacked scenic views and hiking trails.[26] Also unlike other state parks, the Division of State Parks did not keep statistics on its visitors.[26] By 1954, West Virginia's state park system consisted of 40,355 acres (16,331 ha), with only the 7.43-acre (3 ha) Booker T. Washington State Park explicitly open to African Americans.[26][37]

Following the Brown v. Board of Education decision by the United States Supreme Court in May 1954, West Virginia Conservation Commission Director Carl J. Johnson announced the integration of Booker T. Washington State Park, thus allowing whites to utilize the park's facilities.[35][36][38] Johnson also stated that Booker T. Washington was the only state park operated on the basis of segregation and that no further changes would be made to state park policies following the Brown v. Board of Education ruling.[35][36][38] Booker T. Washington remained a day-use state park with picnic facilities;[39] however, by 1957 it was without a supervisor.[40] The park was no longer in operation by 1959 when it was omitted from the listing of state parks in the West Virginia Blue Book[5] and the park was also omitted when the NPS released its 1960 survey of U.S. state parks.[6] The 1958 West Virginia Blue Book did not include a listing of West Virginia state parks.[7]

Significance and legacy

Booker T. Washington State Park was the only state park ever to operate in Kanawha County. When the West Virginia State Park History Committee and former Division of State Parks chief Kermit McKeever published their book Where People and Nature Meet: A History of the West Virginia State Parks in 1988, there was no mention of Booker T. Washington State Park.[41]

See also

Explanatory notes

References

- 1 2 3 Geographic Names Information System; United States Geological Survey. "Geographic Names Information System: Feature Detail Report for Booker T Washington State Park (historical) (Feature ID: 1536226)". Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ↑ West Virginia Legislature 1954, p. 745.

- 1 2 O'Brien 2016, pp. 105–106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Park Named For Negro Educator". Charleston Daily Mail. Charleston, West Virginia. August 5, 1949. p. 8. Retrieved December 10, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- 1 2 West Virginia Legislature 1959, p. 808.

- 1 2 3 National Park Service 1960, p. 53.

- 1 2 West Virginia Legislature 1958

- 1 2 National Park Service Division of Recreation Planning 1950, p. 42.

- 1 2 National Park Service Division of Cooperative Activities 1955, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 Pocatalico Quadrangle, West Virginia (PDF) (Map). 1 : 24,000. 7.5 Minute Series (Topographic). United States Geological Survey. 1958. OCLC 35967285. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Saint Albans Quadrangle, West Virginia (PDF) (Map). 1 : 24,000. 7.5 Minute Series (Topographic). United States Geological Survey. 1958. OCLC 36364802. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Map centered on the location of Booker T. Washington State Park (Map). Google Maps. 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Woodward & McDonald 1986, p. 102.

- ↑ Alum Creek Quadrangle, West Virginia (PDF) (Map). 1 : 24,000. 7.5 Minute Series (Topographic). United States Geological Survey. 1958. OCLC 34325933. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ↑ Powers 1970, p. 5 of the PDF file.

- ↑ "Wine Cellar Park". City of Dunbar website. City of Dunbar, West Virginia. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ↑ Olsen 2008, p. 355.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Haught 1971, pp. 101–107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 DiSarno, Nicole. "The Kanawha Tracts". George Washington Digital Encyclopedia. Mount Vernon, Virginia: Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. Archived from the original on December 17, 2017 – via George Washington Digital Encyclopedia.

- 1 2 Powers 1970, pp. 2–3 of the PDF file.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 West Virginia State University 2014, p. 8 of the PDF file.

- ↑ "Virginia and West Virginia Postal Affairs". Daily Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. May 10, 1876. p. 3. Archived from the original on December 17, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2017 – via Library of Virginia.

- ↑ West Virginia State Department of Education 1907, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ West Virginia State Department of Education 1907, p. 101.

- 1 2 Sweeten 2010, p. 4 of the PDF file.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 O'Brien 2016, p. 105.

- ↑ West Virginia State Park History Committee 1988, p. 8.

- ↑ Sweeten 2010, p. 6 of the PDF file.

- ↑ Collins & Turley 1980, p. 5 of the PDF file.

- ↑ Collins & Turley 1980, p. 2 and 5 of the PDF file.

- 1 2 Collins & Turley 1980, p. 2 of the PDF file.

- ↑ Collins & Turley 1980, p. 3 of the PDF file.

- ↑ Collins & Turley 1980, p. 6 of the PDF file.

- ↑ West Virginia State Park History Committee 1988, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 "Negro W. Va. State Park Opened To Whites". Jet. 6 (5): 8. June 10, 1954. ISSN 0021-5996. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2017 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 "Booker T. Washington Park, Opened To Whites". Delta Democrat Times. Greenville, Mississippi. May 26, 1954. p. 8. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ National Park Service Division of Cooperative Activities 1955, p. 7.

- 1 2 "Public-Owned Negro Park In Charleston Opened To Whites". New York Age. New York. June 12, 1954. p. 22. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ West Virginia Legislature 1957, p. 786.

- ↑ West Virginia Legislature 1957, p. 41.

- ↑ O'Brien 2016, p. 106.

Bibliography

- Collins, Rodney S.; Turley, C. E. (April 29, 1980). National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form: Camp Washington-Carver Complex (PDF). United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- Haught, James A. (January 1971). "Institute: It Springs from Epic Love Story". West Virginia History. 32 (2). Charleston, West Virginia: West Virginia Archives and History. pp. 101–107. OCLC 11393600. Archived from the original on December 17, 2017 – via West Virginia Division of Culture and History.

- National Park Service (1960). State Parks: Areas, Acreages and Accommodations. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior National Park Service. OCLC 5217001 – via Internet Archive.

- National Park Service Division of Cooperative Activities (1955). State Parks: Areas, Acreages and Accommodations. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Division of Cooperative Activities. OCLC 12371526 – via Internet Archive.

- National Park Service Division of Recreation Planning (1950). State Parks: Areas, Acreages and Accommodations. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Division of Recreation Planning. OCLC 966910016 – via Internet Archive.

- O'Brien, William E. (2016). Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-1-61376-360-5. OCLC 973123431 – via Internet Archive.

- Olsen, Brad (2008). Sacred Places, North America: 108 Destinations. San Francisco: Consortium of Collective Consciousness. ISBN 978-1-888729-33-7. OCLC 228099372 – via Internet Archive.

- Powers, Michael J. (July 17, 1970). National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form: Dutch Hollow Wine Cellars (PDF). United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- Sweeten, Lena L. (May 11, 2010). National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form: New Deal Resources in West Virginia State Parks and State Forests (PDF). United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 1, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- West Virginia Legislature (1954). J. Howard Myers, Clerk of the West Virginia Senate, ed. West Virginia Blue Book, 1954. Charleston, West Virginia: Jarrett Printing Company. ISSN 0364-7323. OCLC 1251675.

- West Virginia Legislature (1957). J. Howard Myers, Clerk of the West Virginia Senate, ed. West Virginia Blue Book, 1957. Charleston, West Virginia: Jarrett Printing Company. ISSN 0364-7323. OCLC 1251675.

- West Virginia Legislature (1958). J. Howard Myers, Clerk of the West Virginia Senate, ed. West Virginia Blue Book, 1958. Charleston, West Virginia: Jarrett Printing Company. ISSN 0364-7323. OCLC 1251675.

- West Virginia Legislature (1959). J. Howard Myers, Clerk of the West Virginia Senate, ed. West Virginia Blue Book, 1959. Charleston, West Virginia: Jarrett Printing Company. ISSN 0364-7323. OCLC 1251675.

- West Virginia State Department of Education, ed. (1907). The History of Education in West Virginia Revised Edition. Charleston, West Virginia: Tribune Publishing Company. OCLC 578625783 – via Internet Archive.

- West Virginia State Park History Committee (1988). Where People and Nature Meet: A History of the West Virginia State Parks. Charleston, West Virginia: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-933126-91-6. OCLC 22116273.

- West Virginia State University (2014). Vision 2020: State's Roadmap To The Future (PDF). Institute, West Virginia: West Virginia State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 10, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- Woodward, Susan L.; McDonald, Jerry N. (1986). Indian Mounds of the Middle Ohio Valley: A Guide to Adena and Ohio Hopewell Sites. Blacksburg, Virginia: The McDonald and Woodward Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-939923-00-7. OCLC 15010555 – via Internet Archive.

External links