Adena culture

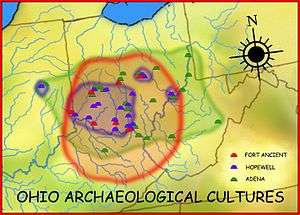

The Adena culture was a Pre-Columbian Native American culture that existed from 1000 to 200 BC, in a time known as the Early Woodland period. The Adena culture refers to what were probably a number of related Native American societies sharing a burial complex and ceremonial system. The Adena lived in an area including parts of present-day Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin, West Virginia, Kentucky, New York, Pennsylvania and Maryland.

Importance

The Adena Culture was named for the large mound on Thomas Worthington's early 19th-century estate located near Chillicothe, Ohio,[1] which he named "Adena",

Adena sites are concentrated in a relatively small area - maybe 200 sites in the central Ohio Valley, with perhaps another 200 scattered throughout Wisconsin, Indiana, Kentucky, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, although those in Ohio may once have numbered in the thousands. The importance of the Adena complex comes from its considerable influence on other contemporary and succeeding cultures.[2] The Adena culture is seen as the precursor to the traditions of the Hopewell culture, which are sometimes thought as an elaboration, or zenith, of Adena traditions.

The Adena were notable for their agricultural practices, pottery, artistic works and extensive trading network, which supplied them with a variety of raw materials, ranging from copper from the Great Lakes to shells from the Gulf Coast.[3][4][5]

Art and religion

Mounds

Lasting traces of Adena culture are still seen in the remains of their substantial earthworks. At one point, larger Adena mounds numbered in the hundreds, but only a small number of the remains of the larger Adena earthen monuments still survive today. These mounds generally ranged in size from 20 feet (6.1 m) to 300 feet (91 m) in diameter and served as burial structures, ceremonial sites, historical markers and possibly gathering places. These earthen monuments were built using hundreds of thousands of baskets full of specially selected and graded earth. According to archaeological investigations, Adena earthworks were often built as part of their burial rituals, in which the earth of the earthwork was piled immediately atop a burned mortuary building. These mortuary buildings were intended to keep and maintain the dead until their final burial was performed. Before the construction of the earthworks, some utilitarian and grave goods would be placed on the floor of the structure, which was burned with the goods and honored dead within. The earthwork would then be constructed, and often a new mortuary structure would be placed atop the new earthwork. After a series of repetitions, mortuary/earthwork/mortuary/earthwork, a quite prominent earthwork would remain. In the later Adena period, circular ridges of unknown function were sometimes constructed around the burial earthworks.[2]

Prominent mounds

| Site | Image | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Adena Mound |  |

The Adena Mound, the type site for the culture, is a registered historic structure near Chillicothe, Ohio. |

| Biggs Site |  |

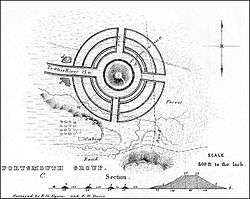

The site, located in Greenup County, Kentucky, is a conical abide surrounded by a series of circular ditches and embankments. It is connected to the Portsmouth Earthworks directly across the Ohio River in Portsmouth, Ohio.[6][7] |

| Criel Mound |  |

A 35-foot (11 m) high and 175-foot (53 m)-diameter conical mound, it is the second largest of its type in West Virginia. It is located in South Charleston, West Virginia. P. W. Norris of the Smithsonian Institution oversaw the excavation. His team discovered numerous skeletons along with weapons and jewelry.[8] |

| Enon Mound |  |

Ohio's second largest conical burial mound, it is believed to have been built by the Adena. |

| Grave Creek Mound |  |

At 69 feet (21 m) high and 295 feet (90 m) in diameter, it is one of the largest conical-type burial mounds in the United States. It is located in Moundsville, West Virginia. In 1838, much of the archaeological evidence in this mound was destroyed when several non-archaeologists tunneled into the mound.[8][8] |

| Miamisburg Mound |  |

Once serving as an ancient burial site, the Miamisburg Mound is the most recognizable landmark in Miamisburg. It is the largest conical burial mound in Ohio, and remains virtually intact. Located in a city park at 900 Mound Avenue, it is an Ohio historical site and serves as a popular attraction and picnic destination for area families. Visitors can climb to the top of the mound via stone-masonry steps. |

| Wolf Plains Group |  |

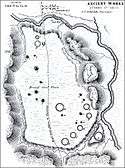

A Late Adena group of 30 earthworks including 22 conical mounds and nine circular enclosures.[9] It is located a few miles to the northwest of Athens, Ohio. |

Shamanism

Although the mounds are beautiful artistic achievements themselves, Adena artists created smaller, more personal pieces of art. Art motifs that became important to many later Native Americans began with the Adena.[10] Motifs such as the weeping eye and cross and circle design became mainstays in many succeeding cultures. Many pieces of art seemed to revolve around shamanic practices, and the transformation of humans into animals—particularly birds, wolves, bears and deer—and back to human form. This may indicate a belief that the practice imparted the animals' qualities to the wearer or holder of the objects. Deer antlers, both real and constructed of copper, wolf, deer and mountain lion jawbones, and many other objects were fashioned into costumes, necklaces and other forms of regalia by the Adena.[11] Distinctive tubular smoking pipes, with either flattened or blocked-end mouthpieces, suggest the offering of smoke to the spirits. The objective of pipe smoking may have been altered states of consciousness, achieved through the use of the hallucinogenic plant Nicotiana rustica. All told, Adena was a manifestation of a broad regional increase in the number and kind of artifacts devoted to spiritual needs.[10]

Stone tablets

The Adena also carved small stone tablets, usually 4 or 5 inches by 3 or 4 inches by .5 inches thick. On one or both flat sides were gracefully composed stylized zoomorphs or curvilinear geometric designs in deep relief. Paint has been found on some Adena tablets, leading archaeologists to propose that these stone tablets were probably used to stamp designs on cloth or animal hides, or onto their own bodies.[11] It is possible that they were used to outline designs for tattooing.[12]

Pottery

Unlike in other cultures, Adena pottery was not buried with the dead or the remains of the cremated, as were other artifacts. Usually Adena pottery was tempered with grit or crushed limestone and was very thick; its decoration was largely plain, cord-marked or fabric marked, although one type bore a nested-diamond design incised into its surface. The vessel shapes were sub-conoidal or flat-bottomed jars, sometimes with small foot-like supports.[13]

Domestic life

Settlement patterns

The large and elaborate mound sites served a nearby scattering of people. The population was dispersed in small settlements of one to two structures. A typical house was built in a circle form from 15 to 45 feet in diameter. The walls were made of paired posts tilted outward, that were then joined to other pieces of wood to form a cone shaped roof. The roof was then covered with bark and the walls may have been bark and/or wickerwork.[14]

Food sources

Their sustenance was acquired through foraging and the cultivation of native plants.

Tools

The Adena ground stone tools and axes. Somewhat rougher slab-like stones with chipped edges were probably used as hoes. Bone and antler were used in small tools, but even more prominently in ornamental objects such as beads, combs, and worked animal-jaw gorgets or paraphernalia. Spoons, beads and other implements were made from the marine conch. A few copper axes have been found, but otherwise the metal was hammered into ornamental forms, such as bracelets, rings, beads, and reel-shaped pendants.[13]

See also

| Preceded by Early Woodland Period |

Adena culture 1000 BC–200 AD |

Succeeded by Ohio Hopewell |

References

- ↑ "Identifying Flint Artifacts/Early Woodland People". Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- 1 2 "Native Peoples of North America–Adena". Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ↑ "Civilizations Of The Americas, The Peoples To The North". Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ↑ "Early Woodland: Northeastern Middlesex Tradition". Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ↑ "Grave Creek Mound Archaeological Complex". Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ↑ "Portsmouth Earthworks-Ohio Central History". Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ↑ Lewis, R. Barry (1996). Kentucky Archaeology. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-1907-6.

- 1 2 3 "Mounds and Mound Builders". Archived from the original on 2008-06-23. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ↑ "The Archaeological Conservancy-2008 Annual Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- 1 2 "Adena-Definition from Answers.com". Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- 1 2 Power, Susan (2004). Early Art of the Southeastern Indians-Feathered Serpents and Winged Beings. University of Georgia Press. pp. 29–34. ISBN 978-0-8203-2501-9.

- ↑ "Virtual First Ohioans".

- 1 2 "Adena Site". Archived from the original on 2009-05-09. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ↑ "The Adena Mounds". Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ↑ "NA Archaeology : Adena". Archived from the original on 2008-06-27. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ↑ Whitaker, Alex. "The Mound Builders". www.ancient-wisdom.com. Retrieved 2017-04-09.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Adena culture. |

- Ohio Memory

- Ohio Historical Society's Archaeology Page

- Virtual First Ohioans's webpage on the Adena

- Introduction to North America's Native People: Adena people

- Ancient Earthworks of Eastern North America Photo Galleries

Coordinates: 38°04′21″N 83°57′03″W / 38.07250°N 83.95083°W