Warren County, North Carolina

Warren County is a county located in the northeastern Piedmont region of the U.S. state of North Carolina, on the northern border with Virginia. As of the 2010 Census, the population was 20,972.[1] Its county seat is Warrenton.[2] It was a center of tobacco and cotton plantations, education, and later textile mills.

Warren County | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Warren County Courthouse in Warrenton | |

Seal | |

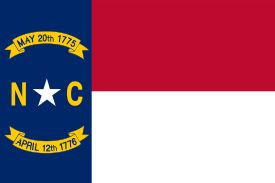

Location within the U.S. state of North Carolina | |

North Carolina's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 36°24′N 78°06′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1779 |

| Named for | Joseph Warren |

| Seat | Warrenton |

| Largest town | Norlina |

| Area | |

| • Total | 444 sq mi (1,150 km2) |

| • Land | 428 sq mi (1,110 km2) |

| • Water | 15 sq mi (40 km2) 3.4%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2018) | 19,807 |

| • Density | 49/sq mi (19/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 1st |

| Website | www |

History

The county was formed in 1779 from the northern half of Bute County. It was named for Joseph Warren of Massachusetts, a physician and general in the American Revolutionary War who was killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Developed as tobacco and cotton farming area. Its county seat of Warrenton became a center of commerce and was one of the wealthiest towns in the state from 1840 to 1860. Many planters built fine homes there.[3]

In the later nineteenth century, the county developed textile mills. In 1881, parts of Warren County, Franklin County, and Granville County were combined to form Vance County. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Warren County's continued reliance on agriculture slowed its development. Many residents migrated to cities for work.

Since the late 20th century, county residents have worked to attract other industrial and business development. Soul City, a "planned community" development, was funded by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). It has not been successful in attracting business and industry, and has not developed as much housing as intended.

Beginning in 1982, Warren County was the site of the Warren County PCB Landfill. Residents of the county have pursued a long environmental justice struggle to remove dangerous pollutants from the site, to improve the health of citizens. The site was not made safe until 2004.

The state of North Carolina evaluated 90 different locations before determining Warren County was the best available site for the PCB landfill. As described in a General Accounting Office (GAO) report published on June 1, 1983, North Carolina wanted the landfill to be in an area bounded by the counties where the PCB spills had occurred, with a minimum area of 16 acres, isolated from highly populated areas, and accessible by road with a deeded right-of-way.[4]

The site of the Warren County PCB landfill at the time of the 1980 census was 66% black. Additionally, the area had a mean family income of $10,367 (amongst the lowest of any of the 90 sites considered), and 90% of the black population living under the poverty level.[4]

The final two locations for the landfill came down to Warren County and a county called Chatham that was eventually dropped because it was publicly owned land. On July 2, 1982, the NAACP made a final attempt to block the creation of the landfill on the basis of racial discrimination. Their plea was denied by the Federal District court stating that race was not an issue because “throughout all the Federal and State hearings and private party suits, it was never suggested that race was a motivating factor in the location of the landfill”.[4]

In response to the court's decision to make Warren County the site of the PCB landfill, protests ensued. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) staged a massive protest where more than 500 protesters were arrested.[5]

Not only did the protest that happened in Warren County impact the community itself, but it emerged as the birthplace of many environmental justice studies in regard to hazardous waste facilities being placed in minority communities. Without the protests and displeasures that the African Americans voiced in Warren County, the United Church of Christ would not have studied the implicit bias found while examining where hazardous waste facilities were placed all over the United States.

Five years later, the United Church of Christ published a report that race was the most significant factor in determining where hazardous waste facilities would be placed. Finding 3 out of every 5 African Americans and Hispanics live in a community housing a toxic waste site. This led to both Presidents George Bush Sr. and Bill Clinton to implement policy to make sure that waste sites would not be placed in completely minority neighborhoods.[5]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 444 square miles (1,150 km2), of which 428 square miles (1,110 km2) is land and 15 square miles (39 km2) (3.4%) is water.[6]

Adjacent counties

- Brunswick County, Virginia - north

- Northampton County - northeast

- Halifax County - east

- Franklin County - south

- Vance County - west

- Mecklenburg County, Virginia - northwest

- Nash County- southeast

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 9,379 | — | |

| 1800 | 11,284 | 20.3% | |

| 1810 | 11,004 | −2.5% | |

| 1820 | 11,158 | 1.4% | |

| 1830 | 11,877 | 6.4% | |

| 1840 | 12,919 | 8.8% | |

| 1850 | 13,912 | 7.7% | |

| 1860 | 15,726 | 13.0% | |

| 1870 | 17,768 | 13.0% | |

| 1880 | 22,619 | 27.3% | |

| 1890 | 19,360 | −14.4% | |

| 1900 | 19,151 | −1.1% | |

| 1910 | 20,266 | 5.8% | |

| 1920 | 21,593 | 6.5% | |

| 1930 | 23,364 | 8.2% | |

| 1940 | 23,145 | −0.9% | |

| 1950 | 23,539 | 1.7% | |

| 1960 | 19,652 | −16.5% | |

| 1970 | 15,810 | −19.6% | |

| 1980 | 16,232 | 2.7% | |

| 1990 | 17,265 | 6.4% | |

| 2000 | 19,972 | 15.7% | |

| 2010 | 20,972 | 5.0% | |

| Est. 2018 | 19,807 | [7] | −5.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[8] 1790-1960[9] 1900-1990[10] 1990-2000[11] 2010-2013[1] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 20,972 people living in the county. 52.3% were Black or African American, 38.8% White, 5.0% Native American, 0.2% Asian, 2.0% of some other race and 1.6% of two or more races. 3.3% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race).

As of the census[12] of 2000, there were 19,972 people, 7,708 households, and 5,449 families living in the county. The population density was 47 people per square mile (18/km²). There were 10,548 housing units at an average density of 25 per square mile (10/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 54.49% Black or African American, 38.90% White, 4.79% Native American, 0.13% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.79% from other races, and 0.88% from two or more races. 1.59% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 7,708 households out of which 28.20% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.20% were married couples living together, 17.30% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.30% were non-families. 26.20% of all households were made up of individuals and 12.20% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 2.97.

In the county, the population was spread out with 23.50% under the age of 18, 8.00% from 18 to 24, 26.30% from 25 to 44, 24.80% from 45 to 64, and 17.40% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females there were 96.60 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.00 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $28,351, and the median income for a family was $33,602. Males had a median income of $26,928 versus $20,787 for females. The per capita income for the county was $14,716. About 15.70% of families and 19.40% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.90% of those under age 18 and 20.80% of those age 65 or over.

Warren County is heavily populated by the Haliwa-Saponi, descendants of a long existing tri-racial isolate deeply rooted in the area.

Law and government

The county favors Democratic candidates over Republicans. In the 2004 election, the county's voters favored Democrat John F. Kerry over Republican George W. Bush by 65% to 35%.[13]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 32.7% 3,214 | 65.2% 6,413 | 2.2% 215 |

| 2012 | 30.9% 3,140 | 68.7% 6,978 | 0.4% 44 |

| 2008 | 30.0% 3,063 | 69.5% 7,086 | 0.5% 46 |

| 2004 | 35.4% 2,840 | 64.4% 5,171 | 0.2% 16 |

| 2000 | 32.4% 2,202 | 67.3% 4,576 | 0.3% 17 |

| 1996 | 29.4% 1,861 | 65.3% 4,141 | 5.3% 337 |

| 1992 | 24.8% 1,767 | 65.4% 4,656 | 9.9% 702 |

| 1988 | 33.6% 2,163 | 66.1% 4,249 | 0.3% 17 |

| 1984 | 40.3% 2,664 | 59.6% 3,946 | 0.1% 8 |

| 1980 | 29.1% 1,582 | 69.1% 3,750 | 1.8% 98 |

| 1976 | 30.8% 1,427 | 68.7% 3,185 | 0.5% 23 |

| 1972 | 59.6% 2,603 | 38.9% 1,698 | 1.5% 65 |

| 1968 | 14.8% 796 | 42.6% 2,293 | 42.6% 2,294 |

| 1964 | 40.1% 1,909 | 59.9% 2,849 | |

| 1960 | 19.3% 717 | 80.7% 2,997 | |

| 1956 | 20.8% 718 | 79.2% 2,733 | |

| 1952 | 18.3% 664 | 81.7% 2,960 | |

| 1948 | 6.9% 192 | 85.8% 2,376 | 7.3% 203 |

| 1944 | 8.9% 242 | 91.1% 2,480 | |

| 1940 | 8.5% 247 | 91.6% 2,676 | |

| 1936 | 4.4% 140 | 95.6% 3,047 | |

| 1932 | 4.0% 110 | 95.8% 2,661 | 0.2% 6 |

| 1928 | 15.7% 379 | 84.3% 2,037 | |

| 1924 | 8.4% 166 | 88.4% 1,742 | 3.2% 62 |

| 1920 | 13.7% 295 | 86.3% 1,865 | |

| 1916 | 15.7% 227 | 84.3% 1,217 | |

| 1912 | 9.8% 112 | 86.2% 987 | 4.0% 46 |

In the 2004 governor's race, Warren County supported Democrat Mike Easley by 74% to 25% over Republican Patrick J. Ballantine.[15] Warren County is represented in the North Carolina House of Representatives by Rep. Michael H. Wray (D-Gaston) and in the North Carolina Senate by Sen. Doug Berger (D-Youngsville). It also forms part of the 1st congressional district, which seat is held by U.S. Rep. G. K. Butterfield (D).

Warren County has a council-manager government, governed by a five-member Board of Commissioners. County commissioners are elected to staggered four-year terms and represent one of five single-member districts of roughly equal population. The council hires a county manager for daily administration.

| District | Name | First elected |

Next election |

Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Barry Richardson | 2004 | 2012 | Chairman |

| 2 | Ulysses S. Ross | 2002 | 2010 | Vice Chairman |

| 3 | Ernest Fleming | 2006 | 2010 | |

| 4 | Bill Davis | 2006 | 2010 | |

| 5 | Jennifer Jordan | 2008 | 2012 |

Warren County is a member of the Kerr-Tar Regional Council of Governments.

Communities

Unincorporated communities

- Afton

- Alert

- Arcola

- Axtell

- Bucks Springs

- Burchette Chapel

- Bute Bridge

- Bute City

- Church Hill

- Cole Bridge

- Coley Spring

- Cool Springs

- Countyline

- Creek

- Creekside

- Crossroads Point

- Crowder Pond

- Drewry

- Eaton Ferry

- Elams

- Elbron

- Embro

- Enterprise

- Epworth

- Essex

- Fishing Creek

- Fiveforks

- Greenwood Village

- Grove Hill

- Hawtree

- Hecksgrove

- Hollister

- Inez

- Jones Springs

- Judkins

- Kimball Point

- Kimballtown

- Lake Gaston

- Lake Gaston Estates

- Largo Lake

- Limertown

- Limertown

- Lirbera

- Littleton

- Lizard Creek

- Manson

- Marmaduke

- Nocava

- Nutbush

- Oakville

- Odell

- Oine

- Old Bethlehem

- Pancrea Springs

- Parktown

- Paschall

- Perry Hill

- Perrytown

- Polar Mountain

- Providence

- Quick City

- Red hill

- Richardson

- Ridgeway

- River

- Roanoke

- Robertson Ferry

- Rocky Hill

- Rose Hill

- Russell Union

- Sandy Creek

- Schoco

- Seoul

- Shocco Creek

- Shocco Springs

- Six Pound

- Smith Creek

- Snow Hill

- Soul City

- Timbuktu

- Tradepost Crossroads

- Vaughan

- Vicksboro

- Warren Hills

- Warren Plains

- Wildwood

- Wise

Notable residents

- North Carolina governors James Turner, William Miller and Thomas Bragg all were born in or lived in Warren County.

- Nathaniel Macon, a Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. senator

- Matt Ransom, US senator, and his brother, Robert Ransom, both Confederate generals.

- Benjamin Hawkins, US senator and Superintendent for Indian Affairs (1798-1818), for the territory south of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi

- John H. Kerr, Congressman

- Eva Clayton, Congresswoman, formerly lived in Soul City

- Braxton Bragg, a Confederate General, and his brother, Confederate Attorney General Thomas Bragg, were from Warrenton.

- Reynolds Price (1933–2011), professor emeritus of English at Duke University and major author and essayist of the South, grew up in the village of Macon.

- Kirkland Donald, United States Navy Admiral[16] (1953 - ), the fifth Director of the U.S. Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program, grew up in the village of Norlina.

- Andrew Marlin, singer, songwriter and musician, member of the group Mandolin Orange.

See also

- List of North Carolina counties

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Warren County, North Carolina

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Wellman, Manly Wade (10 October 2017). The County of Warren, North Carolina, 1586-1917. UNC Press Books. ISBN 9781469617077 – via Google Books.

- "Siting of Hazardous Waste Landfills and Their Correlation With Racial & Economic Status Surrounding Communities" (PDF). General Accounting Office. General Accounting Office (GAO). Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Environmental Justice History". United States Department of Energy. United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Election 2004, CNN.com

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- 2004 Governor's Race Archived 2008-08-04 at the Wayback Machine, State Board of Elections

- Leadership Biographies. Navy.mil. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.