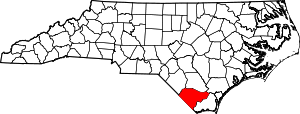

Columbus County, North Carolina

Columbus County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina, on its southeastern border. As of the 2010 census, the population was 58,098.[1] Its county seat is Whiteville.[2]

Columbus County | |

|---|---|

Columbus County Courthouse, Whiteville | |

Location within the U.S. state of North Carolina | |

North Carolina's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 34°16′N 78°40′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1808 |

| Named for | Christopher Columbus |

| Seat | Whiteville |

| Largest city | Whiteville |

| Area | |

| • Total | 954 sq mi (2,470 km2) |

| • Land | 937 sq mi (2,430 km2) |

| • Water | 16 sq mi (40 km2) 1.7%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2018) | 55,655 |

| • Density | 160/sq mi (62/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 7th |

| Website | www |

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 954 square miles (2,470 km2), of which 937 square miles (2,430 km2) is land and 16 square miles (41 km2) (1.7%) is water.[3] It is the third-largest county in North Carolina by land area. There are several large lakes within the county, including Lake Tabor and Lake Waccamaw.

One of the most significant geographic features is the Green Swamp, a 15,907-acre area in the north-eastern portion of the county. Highway 211 passes alongside it. The swamp contains several unique and endangered species, such as the venus flytrap. The area contains the Brown Marsh Swamp, and has a remnant of the giant longleaf pine forest that once stretched across the Southeast from Virginia to Texas.[4]

History

The third largest county in North Carolina was formed in 1808 in the early federal period from parts of Bladen and Brunswick counties. Named for Christopher Columbus, the county was formed by an Act of the General Assembly because of the difficulties of the inhabitants getting to a county seat to transact legal business.[5] The area comprising the county was once part of Bath precinct, organized under the English Crown in 1696. It was at least 50 years after that before the area began to achieve more than meager settlement by European settlers. Until then it was the land of the Waccamaw Siouan Indians.[6]

Waccamaw Siouan Indian tribe

The Waccamaw Siouan Indians are one of eight state-recognized tribes. Their homeland territory is at the edge of Green Swamp in present-day Columbus County. Historically, the "eastern Siouans" had territories extending through the area of Columbus County prior to any European exploration or settlement in the 16th century.

English colonial settlement in what was known as Carolina did not increase until the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Following epidemics of infectious disease, the indigenous peoples suffered disruption and fatalities during the colonial Tuscarora and Yamasee wars. Afterward most of the Tuscarora people migrated north, joining other Iroquoian-speaking peoples of the Iroquois Confederacy in New York State by 1722, when they declared their migration ended and the tribe officially relocated to that area.

The Waccamaw Siouan ancestors retreated for safety to an area of Green Swamp near Lake Waccamaw.[7] Throughout the 19th century, the Waccamaw Siouan were seldom mentioned in the historical record. Toward the end of the century, the U.S. Census recorded common Waccamaw surnames among individuals in the small isolated communities of this area.[8]

In 1910, the earliest-known governmental body of the Waccamaw Indians was officially created, named the Council of Wide Awake Indians. At a time of racial segregation in North Carolina schools, Native American children were grouped with African American children as students. The Council sought to gain public funding for Indian schools, as the Lumbee (then known as Croatan Indians) had achieved in the late 19th century. They also hoped to gain federal recognition as a tribe. This was rare for landless Indians. Federal recognition had been associated with the treaty making that was related to land cessions and removal of Indians to reservations.

The Council opened its first publicly funded school in 1933, and founded others soon after. They continued to have difficulty in getting state funding for schools. Minorities had been effectively disenfranchised in North Carolina since passage of a suffrage amendment in 1900 that created barriers to voter registration. The Council campaigned for federal recognition in 1940 during the President Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, believing it sympathetic to Native Americans. It had passed the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which encouraged tribes to re-establish self-government.[8]

The name Waccamaw Siouan was first officially used in US government documents in 1949, when a bill intended to grant the tribe federal recognition was introduced in Congress by the representative of this district.[8] The bill was defeated in committee the following year. But changes in federal policy following Native American activism in the 1960s and 1970s enabled the Waccamaw Indians to obtain more public funding and economic assistance even without federal recognition.[8]

The Waccamaw Siouan tribe gained recognition in 1971 by the North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs as one of eight state-recognized tribes. The tribe organized as the Waccamaw Siouan Development Association (WSDA), a nonprofit group founded in 1972. The group is headed by a nine-member board of directors, elected by secret ballot in elections open to all enrolled tribal members over the age of 18. In addition, the board includes a chief, whose role is largely symbolic.[8]

Settlement

Some settlers came from Barbados up the Cape Fear River in search of land. Their home island was becoming overcrowded and these people came in search of new opportunities in a new frontier. Other early settlers came mostly from Britain, but a number of other nationalities were represented. Not to be overlooked are the number of freedmen from Virginia and northeastern North Carolina who settled in the area.

Most of the free African Americans of Virginia and North Carolina originated in Virginia where they became free in the seventeenth and eighteenth century before chattel slavery and racism fully developed in the colonies. In his book Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware, author Paul Heinegg said, "When they arrived in Virginia, Africans joined a society which was divided between master and white servant - a society with such contempt for white servants that masters were not punished for beating them to death in 1624. They joined the same households with white servants - working, eating, sleeping, getting drunk, and running away together." A number of Columbus families descend from slaves who were freed before the 1723 Virginia law which required legislative approval for manumissions. Many were landowners who were generally accepted by their white neighbors. Intermarriage between ethnic groups has produced a diverse population, with many descendants today not truly understanding their family history due to assumptions based on appearance.[9]

John Burgwin (1731-1803), colonial officer and merchant, left his native South Wales, England after his elder brother inherited their father's estate. Seeking his own fortune elsewhere, by early in 1750/51, Burgwin was employed as a merchant in Charleston, South Carolina with the firm of Hooper, Alexander and Company. The firm did business in Wilmington, and Burgwin apparently moved to the Cape Fear River area of North Carolina shortly thereafter. He built what is now known as the Burgwin-Wright house in Wilmington, which served as Lord Cornwallis' headquarters while he occupied the city in 1781. In addition to his Wilmington townhouse, Burgwin inherited from his wife the Hermitage Plantation and adjoining Castle Haynes Plantation. He also owned Marsh Castle at Lake Waccamaw in Columbus (then Bladen) County.[10]

At least two skirmishes of the American Revolution were fought on Columbus soil, one was the Battle of Seven Creeks near Pireway. After this battle, General Joseph Graham said "We fixed the wounded, buried the dead, and then marched to Marsh Castle and encamped on the White Marsh." The next day they learned of Cornwallis' surrender as they marched by Lake Waccamaw and joined Colonel Smith above Livingston Creek.[11]

The other skirmish was at Brown Marsh. General Graham wrote "The army continued to move down the Raft Swamp, from thence to Brown Marsh, where General Butler had had a battle with the British and Tories some weeks before, and encamped for several days near that place."[11] Bullets from this battle have been plowed up on a farm on the east side of the Brown Marsh.

Some of those who joined the Patriots:

- Stephen Smith (1746-1784) who married Joanna Council (1753-1833), daughter of Capt James Council (1716-1804). Stephen is buried in Hallsboro, his grave marked with a Revolutionary War plaque. James Council was Paymaster of Troops, member of the Provincial Congress which sat at Halifax, North Carolina and Wilmington District Bladen County Regiment company commander at the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge.

- William Norris (1766-1860), listed in the 1860 census as a "Farmer and Soldier of the American Revolution."

- Coleman Nichols (1737-1825)

- Elias Duncan (1750-1830, Militia, Wilmington District[12]

William Bartram, botanist from Pennsylvania, journeyed to Lake Waccamaw to study the flora and fauna of the region in the 1770s. William was the son of John Bartram, the first person to form a botanic garden for American plants in America. William chronicled his travels through the American South in his extensive and insightful book, Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida..., published in 1791.[13]

Firsts in Columbus County:

- First bale of cotton grown in 1815 by Dr. Formy Duvall

- First schoolhouse in Whiteville built shortly after the Civil War

- First house in Chadbourn erected 1882

- First mayor of Chadbourn was James B. Chadbourn, Jr.

- First schoolhouse in Chadbourn built in 1886 by James H. Chadbourn, Jr.

- First tobacco grown in county in 1896 by John Morley near Fair Bluff

- First tobacco warehouse in 1896 at Fair Bluff

- First strawberries for shipment grown in 1896 by Joseph A. Brown

- First bank in the county was Bank of Whiteville in 1903[11]

COLCOR

From January 1979 through December 1982,[14] State and Federal investigators conducted Operation NC Gateway, an investigation into the activities of several elected officials in Brunswick and Columbus counties. Law enforcement seized 37 million dollars of illegal drugs, and arrested several leading citizens in the area. The scandal was labeled "COLCOR" in the press, shorthand for Columbus Corruption.[15] The federal investigation culminated in federal convictions of former Brunswick County Sheriff Herman Strong and former Shallotte Police Chief Hoyal Varnum Jr., among other government officials.[16] The 1983 street value of the narcotics in Strong and his co-conspirators’ criminal enterprise was $180 million.[17]

COLCOR's success was largely due to the deep undercover work by FBI Special Agent Robert Drdak. His testimony to the Grand Jury led to the arrest of a long list of prominent Brunswick and Columbus County citizens. In addition, former U.S. Attorney, Samuel Currin, was the force behind operations ColCor and Operation Gateway. The special investigative grand jury in Brunswick County indicted 22 persons,[17] and 35 were indicted in Columbus County.[14] Among those indicted were:[14][18][19]

- Brunswick County Sheriff Herman Strong (numerous charges of conspiring to smuggle drugs, providing protection to drug smugglers, accepting bribes and two incidents of drug smuggling marijuana and methaqualone tablets). Strong was released from prison on June 17, 1987, after serving less than four years.[17]

- Shallotte Police Chief Hoyal "Red" Varnum (conspiring to possess with intent to distribute 1,100 to 1,400 pounds of marijuana)

- Hoyal's brother Steve Varnum (a past Chairman of the Brunswick County Commissioners),

- Lake Waccamaw Police Chief L. Harold Lowery (racketeering in connection with taking $1,650 in bribes for protection money)

- Former Columbus County Commissioner Edward Walton Williamson (who gave the undercover agent money to deal with Star News reporter Judith Tillman and send her back to Alabama)[20]

- District Court Judge J. Wilton Hunt (racketeering and interstate gambling) A federal judge sentenced Hunt to 14 years in prison and a $10,000 for his role in the corruption ring.[17]

- State Rep. G. Ronald Taylor, (burning three warehouses belonging to another state senator who was Taylor's competition in the farm-implement business)

- Lt. Governor James C. Green (charged with taking a $2,000 bribe and conspiring to take $10,000 in bribes a month) [18][19] The jury found insufficient evidence for the charges and acquitted Green.[21]

- NC State Senator R C Soles was indicted on federal charges of aiding and abetting a former Columbus County commissioner in obtaining bribes from undercover FBI agents, conspiracy, vote-buying and perjury, but these charges were later dismissed.[22]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 3,022 | — | |

| 1820 | 3,912 | 29.5% | |

| 1830 | 4,141 | 5.9% | |

| 1840 | 3,941 | −4.8% | |

| 1850 | 5,909 | 49.9% | |

| 1860 | 8,597 | 45.5% | |

| 1870 | 8,474 | −1.4% | |

| 1880 | 14,439 | 70.4% | |

| 1890 | 17,856 | 23.7% | |

| 1900 | 21,274 | 19.1% | |

| 1910 | 28,020 | 31.7% | |

| 1920 | 30,124 | 7.5% | |

| 1930 | 37,720 | 25.2% | |

| 1940 | 45,663 | 21.1% | |

| 1950 | 50,621 | 10.9% | |

| 1960 | 48,973 | −3.3% | |

| 1970 | 46,937 | −4.2% | |

| 1980 | 51,037 | 8.7% | |

| 1990 | 49,587 | −2.8% | |

| 2000 | 54,749 | 10.4% | |

| 2010 | 58,098 | 6.1% | |

| Est. 2018 | 55,655 | [23] | −4.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[24] 1790-1960[25] 1900-1990[26] 1990-2000[27] 2010-2013[1] | |||

As of the census[28] of 2000, there were 54,749 people, 21,308 households, and 15,043 families residing in the county. The population density was 58/sq mi (23/km²). As of 2004, there were 24,668 housing units at an average density of 26/sq mi (10/km²). The racial makeup for the county was 68.9% White, 23.1% Black or African American, 5.1% Native American, 0.2% Asian, 4.7% from other races, and 0.6% from two or more races. 2.7% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

By 2005 62.3% of the county population was White, 31.1% of the population was African-American, and 3.2% of the population was Native American. According to the 2010 census, 1,025 people in Columbus County self-identify as Waccamaw Siouan.[29] 2.8% of the population was Latino.

There were 21,308 households out of which 31.50% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.80% were married couples living together, 15.80% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.40% were non-families. 26.50% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.70% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.50 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the county, the population was spread out with 25.70% under the age of 18, 8.70% from 18 to 24, 27.40% from 25 to 44, 24.40% from 45 to 64, and 13.80% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females there were 92.60 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.40 males.

The 2003 median income for a household in the county was $27,659, and the median income for a family was a little more than $33,800. Males had a median income of $28,494 versus $19,867 for females. The per capita income for the county was $14,415. About 17.60% of families and 20.30% of the population were below the poverty line, including 30.00% of those under age 18 and 25.50% of those age 65 or over.

Columbus County led the state in opioid pills per person from 2006-2012 averaging 113.5 pills per person per year.[30]

Economics

The economy of Columbus County centers on agriculture and manufacturing. Columbus farmers produce crops such as pecans and peanuts, along with soybeans, potatoes, and corn. Cattle, poultry, and catfish are other agricultural products in the county.

Factories in the region produce textiles, tools, and plywood. Household products such as doors, furniture, and windows are also manufactured in Columbus.[31]

Carolina Southern stopped railroad service to the county in 2012, and efforts to restore service have proven difficult.[32] However, as of July 2014, positive developments were reported to return railroad service to the area, which was considered integral to spur economic development.[33]

in July 2014, Carolina Southern agreed to begin the process of allowing the counties of Horry County, South Carolina, Marion, South Carolina and Columbus County, NC to assume control of the area rail lines. The goal was to repair the railroad tracks and bridges through local governments and then to find a buyer to re-establish service to the area.[34] A public hearing on the matter was held on October 6, 2014.[35] During that meeting, the Columbus County Commissioners voted to support the initiative to restart rail service with a 10-year grant for the program. Some of the commissioners may not have revealed that they will benefit from the re-establishment of rail service.[36] The Horry County Council in October 2014 also voted to provide funding to reestablish railroad service to the area.[37] Although originally it was thought service could be restored as early as spring 2015,[38] however, the sale of the railroad was not completed until August, 2015 to R.J. Coleman Railroad..[39] A new target date of February 2016 was announced, as millions of dollars are expected to be spent repairing the rail lines that have been idle since 2011.[40]

Law and government

Columbus County is governed by a board of seven Commissioners, elected from single-member districts.

The county is a member of the regional Cape Fear Council of Governments, where it participates in area planning on a variety of issues.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 60.1% 14,272 | 38.2% 9,063 | 1.7% 397 |

| 2012 | 53.4% 12,941 | 45.6% 11,050 | 1.0% 252 |

| 2008 | 53.5% 12,994 | 45.6% 11,076 | 0.9% 212 |

| 2004 | 50.8% 10,773 | 48.8% 10,343 | 0.4% 75 |

| 2000 | 45.3% 8,342 | 54.2% 9,986 | 0.5% 97 |

| 1996 | 37.0% 6,017 | 55.4% 9,019 | 7.6% 1,244 |

| 1992 | 28.9% 5,462 | 60.6% 11,469 | 10.5% 1,985 |

| 1988 | 41.9% 6,659 | 57.8% 9,172 | 0.3% 51 |

| 1984 | 51.1% 9,150 | 48.8% 8,728 | 0.2% 26 |

| 1980 | 34.6% 5,522 | 64.1% 10,212 | 1.3% 206 |

| 1976 | 22.1% 3,184 | 77.4% 11,148 | 0.5% 69 |

| 1972 | 70.6% 8,468 | 27.6% 3,305 | 1.8% 214 |

| 1968 | 26.2% 3,881 | 28.6% 4,243 | 45.2% 6,693 |

| 1964 | 33.2% 4,471 | 66.8% 9,004 | |

| 1960 | 25.9% 3,655 | 74.1% 10,455 | |

| 1956 | 22.8% 2,300 | 77.2% 7,805 | |

| 1952 | 30.2% 3,001 | 69.8% 6,941 | |

| 1948 | 15.0% 1,105 | 74.8% 5,511 | 10.2% 753 |

| 1944 | 21.4% 1,552 | 78.7% 5,717 | |

| 1940 | 13.7% 934 | 86.3% 5,900 | |

| 1936 | 16.0% 1,214 | 84.0% 6,359 | |

| 1932 | 12.6% 739 | 86.6% 5,098 | 0.9% 53 |

| 1928 | 55.3% 3,533 | 44.7% 2,854 | |

| 1924 | 36.9% 1,629 | 62.5% 2,757 | 0.6% 26 |

| 1920 | 36.4% 1,783 | 63.6% 3,111 | |

| 1916 | 38.2% 1,327 | 61.7% 2,143 | 0.1% 2 |

| 1912 | 5.7% 155 | 61.4% 1,668 | 32.9% 892 |

Columbus County Animal Shelter

Columbus County maintains an animal shelter at 288 Legion Drive in Whiteville, NC. It has been the subject of critics - both government regulators and animal welfare activists.[42] Problems have been reported in its operations for "years and years and years." [43] In the past, the shelter has been fined [44] and has been warned by state regulators for shortcomings on various issues.[45]

In September 2015, a new manager was hired to combat these issues,[46] and he announced an ambitious plan to improve the shelter. In late October 2015, WECT reported that conditions at the shelter were improving, highlighting a large donation from Austria that was made possible by coordination on Facebook. The story also enumerated changes that the new director had made to improve conditions.[42] As of November 2015, the volunteers maintain a Facebook page showing the animals the shelter has available for adoption.[47]

Libraries

The county maintains a system of 6 libraries. The first public library for the county opened in 1921.[48]

Prisons

There are two state prisons in the county, one at Tabor City, the Tabor City Correctional Institution, and one at Brunswick,[49]

Sheriff Department

The Sheriff's office provides law enforcement services for the county as well as operating the Columbus County Detention Center. As of January 2016, the current sheriff was Lewis Hatcher.[50] In 2018, Republican candidate Jody Greene appeared to win by 37 votes. Since the election, the state board of elections has not allowed the local board of elections to certify the vote because of alleged fraud. Three issues have been outlined. 1. Evidence suggests that Jody Greene did not keep a permanent residence in Columbus County for the 12 calendar months before he filed to run for office.[51] 2. Jody Greene paid a consulting firm to manage absentee ballots, among other political activities, that has been accused of voter fraud. 181 absentee ballots are in question.[52][53] 3. Polling Issues that cast doubt on the voting process.[54] While Mr. Greene was sworn in as sheriff, the state board of elections and state attorney general said that it was in error.[55] A hearing in the matter was scheduled for January 18, 2019,[56] however after several delays it was agreed that neither candidate would serve until "state officials can sort out who officially won November’s election"[57] An attorney representing one of the candidates was arrested on drug charges.[58]

Communities

Cities

- Whiteville (named county seat in 1832 [45])

Towns

- Boardman

- Bolton

- Brunswick

- Cerro Gordo

- Chadbourn

- Fair Bluff

- Hallsboro

- Lake Waccamaw

- Sandyfield

- Tabor City (Incorporated as a town)

Townships

- Bogue

- Bolton

- Bug Hill

- Cerro Gordo

- Chadbourn

- Fair Bluff

- Lees

- Ransom

- South Williams

- Tatums

- Waccamaw

- Welch Creek

- Western Prong

- Williams

- Whiteville

Census-designated places

Unincorporated areas

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "The Green Swamp", My Reporter, April 2009

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 88.

- Rogers, James A, editor (1946). Columbus County, North Carolina 1946. Whiteville, North Carolina: The New Reporter.

- William S. Powell, Encyclopedia of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 1170.

- Powell, Encyclopedia of North Carolina, 1170.

- Heinegg, Paul (2009). "Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware". Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Lennon, Donald R. (1979). "John Burgwin". NCPedia. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Rogers, Columbus County, North Carolina 1946

- Roster of Soldiers from North Carolina in the American Revolution. Seeman Press, Durham, North Carolina: North Carolina Daughters of the American Revolution. 1932. p. 374.

- Bartram, William (1791). Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws; Containing An Account of the Soil and Natural Productions of Those Regions, Together with Observations on the Manners of the Indians. Philadelphia: James & Johnson.

- "Operation N.C. Gateway stings Brunswick's former sheriff in early 80s | BrunswickBeacon.com". www.brunswickbeacon.com. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- "COLCOR REDUX". crime.blogs.com. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- "Operation N.C. Gateway stings Brunswick's former sheriff in early 80s". brunswickbeacon.com. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- "Under investigation: A tale of three decades - BrunswickBeacon.com". brunswickbeacon.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "COLCOR REDUX". CRIME REPORT. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- AP. "GRAND JURY INDICTS LIEUT. GOV. GREEN OF NORTH CAROLINA". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Then, Scott Nunn Back. "1982: FBI arrests Waccamaw police chief, 20 others". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Political Grudges Are Nothing New". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Timeline of R.C. Soles' career". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Commission on Indian Affairs, North Carolina Department of Administration. (2010). "Total Population by Tribe by County in North Carolina." "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-04-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Columbus led state in opioid pills per person; Unsealed data reveals 'virtual road map to the opioid epidemic'". The News Reporter. 2019-07-30. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- http://mangowebdesign.com, Website design and web development by Mango Web Design. "Columbus County (1808) - North Carolina History Project". North Carolina History Project. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- Jones, Steve. "STB filing: Railroad revenue not important in reaching a decision | Business". MyrtleBeachOnline.com. Archived from the original on 2014-04-16. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- "Tabor-Loris Tribune – July 16, 2014". tabor-loris.com. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- "Local news". The Sun News in Myrtle Beach, SC. myrtlebeachonline.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-28. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- "Tabor-Loris Tribune – September 17, 2014". tabor-loris.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- Justin Smith (2014-10-07). "Commissioner could benefit from railroad receiving county incentives". wect.com. WECT TV6. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- "CONWAY: Horry County Council approves $1.8 m commitment to help purchase Carolina Southern Railroad | Local News | MyrtleBeachOnline.com". myrtlebeachonline.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-13. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- "Carolina Southern could roll again by next spring | Business | MyrtleBeachOnline.com". myrtlebeachonline.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-16. Retrieved 2014-12-06.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-09-10. Retrieved 2015-11-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Done Deal: Railroad that serves Columbus County changes hands". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- http://www.wect.com/clip/11957953/new-animal-control-director-seeks-to-improve-columbus-co-shelter%5B%5D

- "Columbus County > Departments > Animal Control". columbusco.org. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Columbus County Animal Shelter fined again". WWAY TV3. 24 June 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "NCDA&CS Veterinary Division Animal Welfare Section Civil Penalties and Other Legal Issues". ncagr.gov. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Log In or Sign Up to View". facebook.com. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Columbus County Public Library System Copy". Columbus County Public Library System Copy. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "North Carolina Division of Prisons". doc.state.nc.us. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Office, Columbus County Sheriff's. "Home". columbuscountysheriff.com. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- McAdams, Ann. "Evidence indicates Sheriff Jody Greene may not live in Columbus County". wect.com. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- McAdams, Ann. "NC election fraud: Concerning number of absentee ballots not returned in Columbus Co". wect.com. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- Featherston, Emily. "Columbus County sheriff paid group under investigation for NC9 election fraud". wect.com. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- Tracy, Kailey. "Board of Elections director says human error likely caused Columbus Co. poll issues". wect.com. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- "UPDATE: SBOE says that Hatcher is still sheriff". The News Reporter. 2018-12-20. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- News, WWAY (2019-01-14). "Hearing scheduled for Lewis Hatcher's injunction". WWAY TV. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- Brosseau, Carli (February 8, 2019). "Columbus County sheriff's candidates agree that, for now, neither will be sheriff". Raleigh News & Observer. Retrieved 2019-08-24.

- "Whiteville attorney cited for marijuana possession". The News Reporter. 2019-03-04. Retrieved 2019-08-24.