Julius (restaurant)

Julius' is a tavern in Manhattan's Greenwich Village neighborhood in New York City, located at 159 West 10th Street at Waverly Place. It is often called the oldest continuously operating gay bar in New York City. Its management, however, was actively unwilling to operate as such, and harassed gay customers until 1966.

Julius' Bar | |

South (front) facade in 2008 | |

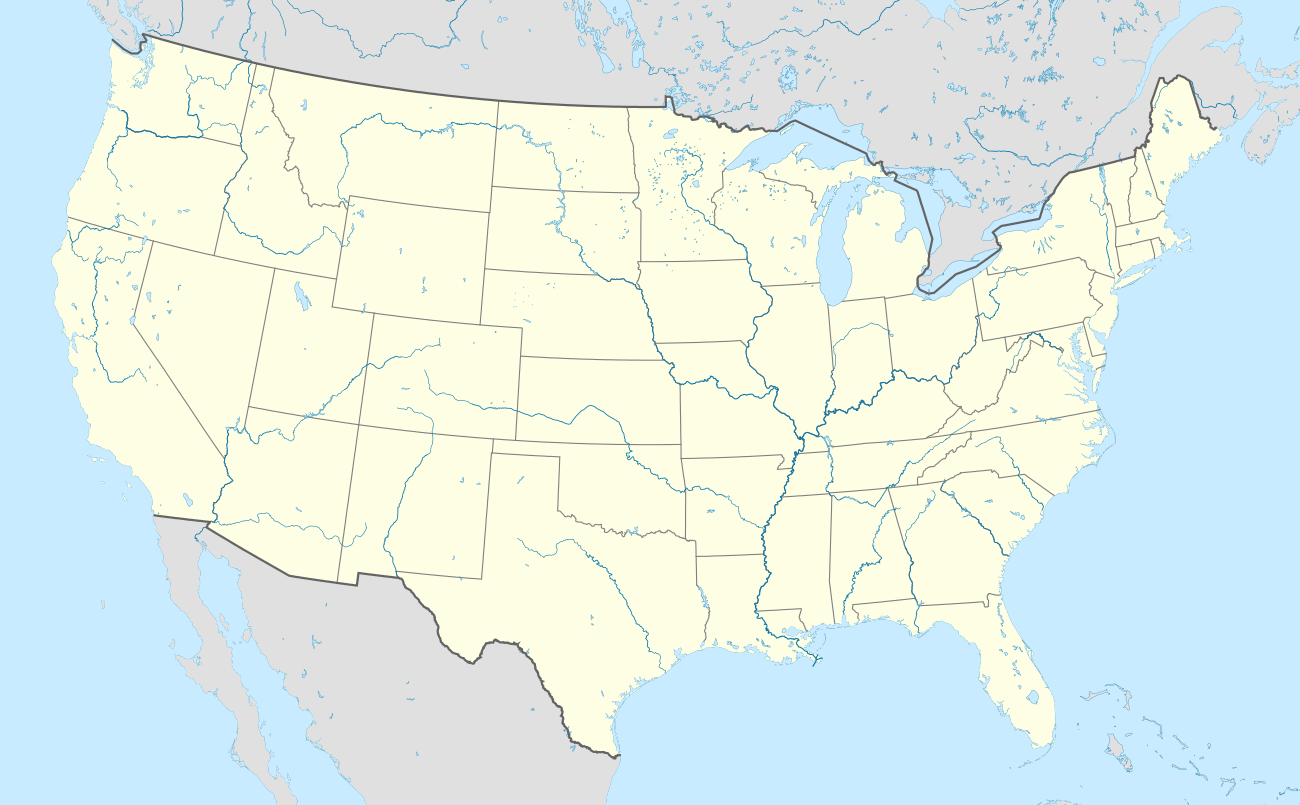

Location in New York City  Julius (restaurant) (New York City)  Julius (restaurant) (New York)  Julius (restaurant) (the United States) | |

| Location | West Village, Manhattan, NY |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°44′4″N 74°0′5″W |

| Built | 1867 |

| Website | juliusbarny |

| NRHP reference No. | 16000242 |

| Added to NRHP | April 20, 2016 |

The April 1966 "Sip-In" at Julius, located a block northeast of the Stonewall Inn, established the right of homosexuals to be served in licensed premises in New York.[1] This action helped clear the way for gay premises with state liquor licenses.

Newspaper articles on the wall indicate it was the favorite bar of Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote and Rudolf Nureyev.[2] In 2016, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[3]

History

According to bar lore it was established around 1867 – the same year as the Jacob Ruppert Brewery in the Yorkville neighborhood. Per the current owner, the establishment opened in 1864. Barrels stamped "Jacob Ruppert" are used for tables. Vintage photos of racing horses, boxers and actors are on the wall include drawings of burlesque girls as well as an image signed by Walter Winchell saying that he loves Julius.[4] The bar became a popular watering hole in the 1930s and 1940s due to its proximity to the jazz club Nick's in the Village.[4]

By the late 1950s, it was attracting gay patrons. At the time the New York State Liquor Authority had a rule that ordered bars not to serve liquor to the disorderly, and homosexuals per se were considered "disorderly." Bartenders would often evict known homosexuals or order them not to face other customers in order to avoid cruising. Despite this, gay men continued to be a large part of the clientele into the early 1960s, and the management of Julius, steadfastly unwilling for it to become a gay bar, continued to harass them.[5]

The Sip-In

On April 21, 1966 members of the New York Chapter of the Mattachine Society staged a "Sip-In" at the bar which was to change the legal landscape.[6] Dick Leitsch and Craig Rodwell, the society's president and vice president respectively, and another society activist, John Timmons, planned to draw attention to the practice by identifying themselves as homosexuals before ordering a drink in order to bring court scrutiny to the regulation. The three were going to read from Mattachine stationary "We are homosexuals. We are orderly, we intend to remain orderly, and we are asking for service."

The three first targeted the Ukrainian-American Village Restaurant at St. Mark's Place and Third Avenue in the East Village, Manhattan which had a sign, "If you are gay, please go away." The three showed up after a New York Times reporter had asked a manager about the protest and the manager had closed the restaurant for the day.[1] Secondly, they targeted a bar called Dom's, which was also closed.[7] They then targeted a Howard Johnson's and a bar called Waikiki where they were served in spite of the note with a bartender saying later, "How do I know they're homosexual? They ain't doing nothing homosexual."

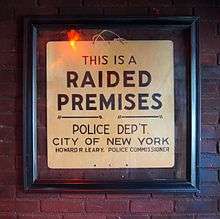

Frustrated, they then went to Julius, where a clergyman had been arrested a few days earlier for soliciting sex. A sign in the window read, "This is a raided premises." The bartender initially started preparing them a drink but then put his hand over the glass, which was photographed. The New York Times ran the headline "3 Deviates Invite Exclusion by Bars" the next day.[8]

The Mattachine Society then challenged the liquor rule in court and the courts ruled that gays had a right to peacefully assemble, which undercut the previous SLA contention that the presence of gay clientele automatically was grounds for charges of operating a "disorderly" premise. With this right established a new era of licensed, legally operating gay bars began. The bar now holds a monthly party called Mattachine.

Subsequent history

Scenes from the movie Boys in the Band (1970) were shot at the bar.[2]

Julius was the site of a scene shot in the movie Next Stop, Greenwich Village (1976). The scene included Lenny Baker and Christopher Walken.

In August 2007, the bar was closed briefly after being seized for non-payment of taxes.[9]

Julius was the site of a scene in Ira Sachs' gay indie movie Love is Strange (2014). The scene included John Lithgow and Alfred Molina. The wrap party also took place at the bar.[10]

Julius was also featured prominently in the 2018 film Can You Ever Forgive Me?, starring Melissa McCarthy and Richard E. Grant.

In 2012, in response to research and a request from the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, the New York State Division for Historic Preservation determined Julius eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. The letter of eligibility stated, "The building meets the criteria for listing in the area of social history for its association with the LGBT civil rights movement." It mentioned that the building's interior "remains remarkably intact from the 1966 era of significance."[11] It was listed in 2016.[3]

In fiction

The Julius's denial of service was dramatized in the film Stonewall (1995). However, filmmakers moved the denial of service from Julius to the Stonewall Inn.

See also

- List of pre-Stonewall LGBT actions in the United States

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan below 14th Street

References

- Watson, Steve (June 17, 2008). "Before Stonewall". Village Voice. Archived from the original on July 1, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- Biederman, Marcia (June 11, 2000). "Journey to an Overlooked Past". The New York Times. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- "Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties 4/25/16 through 4/29/16". U.S. National Park Service. May 6, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- Moss, Jeremiah (December 21, 2007). "Julius' Bar". Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- "Gay Sixties". Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- "Remembering a 1966 'Sip-In' for Gay Rights". Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- Pitman, Gayle E. (2019). The Stonewall Riots: Coming Out in the Streets. New York: Abrams Books. p. 41-45. ISBN 9781419737206..

- Johnson, Thomas A. (April 22, 1966). "3 Deviates Invite Exclusion by Bars; But They Visit Four Before Being Refused Service, in a Test of S.L.A. Rules". The New York Times. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- EaterWire AM Edition: Julius Closed, Seized For Nonpayment of Taxes – eater.com – August 29, 2007 Archived April 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Sightings…". Page Six. New York Post. October 3, 2013. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- "West Village Julius' Bar Eligible for State and National Historic Registers". Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Retrieved September 30, 2014.