Vannes

| Vannes Gwened | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prefecture and commune | |||

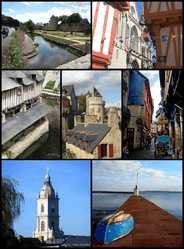

Montage of Vannes Top left: View of Ramparts Garden of Vannes and Gaillard Castle Museum; Top right: Saint Peters Cathedral; Middle left: Vieux lavoirs, old washing place; Center: Connetable Tower; Middle right: Intra Muros narrow street; Bottom left: Saint Paterne Church; Bottom right: Conleau Pier | |||

| |||

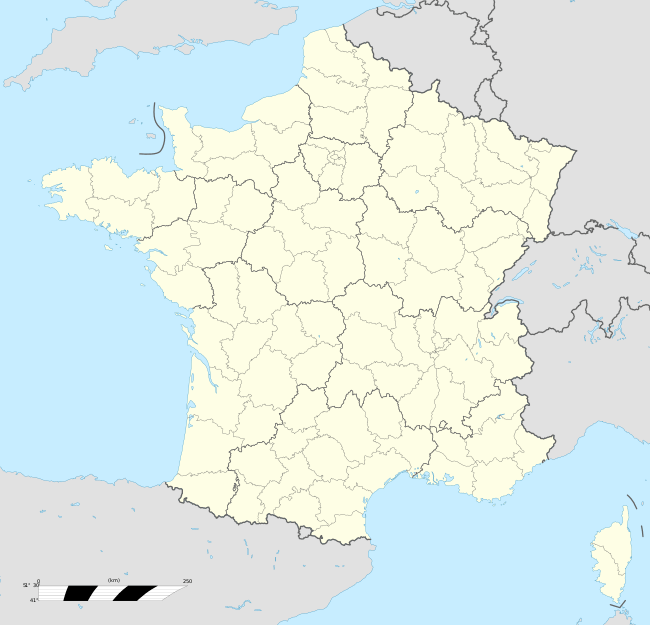

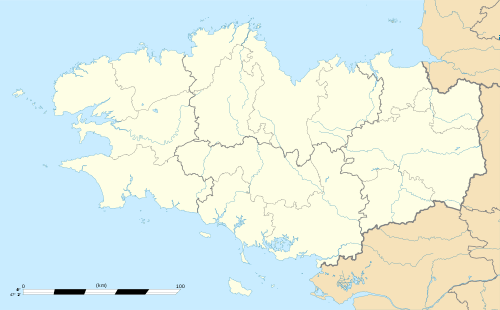

Vannes Location within Brittany region  Vannes | |||

| Coordinates: 47°39′21″N 2°45′37″W / 47.6559°N 2.7603°WCoordinates: 47°39′21″N 2°45′37″W / 47.6559°N 2.7603°W | |||

| Country | France | ||

| Region | Brittany | ||

| Department | Morbihan | ||

| Arrondissement | Vannes | ||

| Canton | Vannes-1, 2 and 3 | ||

| Intercommunality | Golfe du Morbihan - Vannes Agglomération | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor (2011–2016) | David Robo | ||

| Area1 | 32.3 km2 (12.5 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2012)2 | 52,648 | ||

| • Density | 1,600/km2 (4,200/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | ||

| INSEE/Postal code | 56260 /56000 | ||

| Elevation |

0–56 m (0–184 ft) (avg. 22 m or 72 ft) | ||

|

1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. 2 Population without double counting: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | |||

Vannes (French pronunciation: [van]; Breton: Gwened) is a commune in the Morbihan department in Brittany in north-western France. It was founded over 2,000 years ago.[1]

Geography

Vannes is located on the Gulf of Morbihan at the mouth of two rivers, the Marle and the Vincin. It is around 100 kilometres (62 miles) northwest of Nantes and 450 km (280 mi) south west of Paris. Vannes is a market town and often linked to the sea.

History

The name Vannes comes from the Veneti, a seafaring Celtic people who lived in the south-western part of Armorica in Gaul before the Roman invasions. The region seems to have been involved in a cross channel trade for thousands of years, probably using hide boats and perhaps Ferriby Boats.[2] Wheat that apparently was grown in the Middle East was part of this trade.[3] At about 150 BC the evidence of trade (such as Gallo-Belgic coins) with the Thames estuary area of Great Britain dramatically increased.[4]

The Veneti were defeated by Julius Caesar's fleet in 56 BC in front of Locmariaquer; many of the Veneti were then either slaughtered or sold into slavery. The Romans settled a town called Darioritum in a location previously belonging to the Veneti. From the 5th to the 7th century, the remaining Gauls were displaced or assimilated by waves of immigrant Britons fleeing the Saxon invasions of Britain. Under the Breton name Gwened (also derived from the Veneti), the town was the center of an independent principality or kingdom variously called Bro-Wened ("Vannes") or Bro-Ereg ("land of Gwereg"), the latter for a prominent member of its dynasty, which claimed descent from Caradog Strongarm. The diocese of Vannes was erected in the 5th century. The Council of Vannes was held there in 461. The realm annexed Cornouaille for a time in the early 6th century but was permanently joined with Domnonia under its king and saint Judicaël around 635.

In 1342, Vannes was besieged four times between forces from both sides of the Breton War of Succession. The city's defending commander, Olivier de Clisson IV was captured by the English, but finally released. The French eventually executed him on suspicion that the ransom was unusually low and therefore he may have been a traitor.

In 1759, Vannes was used as the staging point for a planned French invasion of Britain. A large army was assembled there, but it was never able to sail following the French naval defeat at the Battle of Quiberon Bay in November 1759.

In 1795, during the French Revolution, French forces based in Vannes successfully repelled a planned British-Royalist invasion.

Population

Inhabitants of Vannes are called Vannetais.

| Year | 1911 | 1936 | 1954 | 1962 | 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2008 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 23,748 | 24,068 | 25,089 | 30,411 | 36,576 | 40,359 | 42,178 | 45,644 | 51,759 | 52,983 | 52,648 |

Breton language

The municipality launched a linguistic plan through Ya d'ar brezhoneg on 12 October 2007.

In 2008, 7.71% of the children attended the bilingual schools in primary education.[5]

Transport

Train

The Gare de Vannes railway station offers connections to Quimper, Rennes, Nantes, Paris and several regional destinations.

With the fast train TGV, the journey takes:

– 30 minutes to Lorient,

– 1 hour to Nantes or Rennes,

– 3.5 to 4 hours to Paris.

The Transport express régional or TER is a slower train to join railway stations in the close neighborhood, as Auray or Questembert.

There is no direct railway from Vannes to Saint-Brieuc (118 km away in the north of Brittany), so the train from Vannes to Saint Brieuc goes via Rennes, which doubles the travel time and cost: it takes 2 to 3 hours to go from Vannes to Saint Brieuc by train.

Car

Two highways, in the north of Vannes, provide fast connections by car:

– N165: drive west to Lorient (58 km) and Quimper (122 km), south east to Nantes (111 km)

– N166: drive north east to Rennes (113 km)

+ a network of small roads connects Vannes to smaller cities.

There is no highway from Vannes to Saint-Brieuc, so the way to northern Brittany consists of small roads. The lack of highway or railway between Vannes and Saint-Brieuc (118 km north) cuts the communications between northern and southern Brittany, and limits Brittany economic performance.

Airplanes

Vannes has a small airfield in the village of Monterblanc, called Vannes-Meucon airport, or "Vannes – Golfe du Morbihan airport". It used to be a military airport, but it is now dedicated to general aviation aircraft. It belongs to Vannes Agglomeration community, the group of cities gathered around Vannes, and the main users of this airfield are Vannes flying club, the local ultralight aviation club, and Vannes school of skydiving.

Bus

There are 2 bus networks in Vannes:

– Kicéo, proposes short travels starting from Vannes Place de la Republique on behalf of Vannes Agglomeration community,

– CAT, propose longer travel starting from the railway station on behalf of Morbihan.

So there are 2 central bus stations in Vannes: one on Place de la Libération, the other at the railway station.

Bike

Vannes city had a public bicycle rental program, called Velocea based on the same idea as the Paris Vélib'.

Hundreds of bicycles are available in 20 automated rental stations each with 10 to fifteen bikes/spaces.

Each Velocea service station is equipped with an automatic rental terminal and stands for bicycles.

The bicycles were robust and heavy 18 kilograms (40 lb), and the user could take a bike in any station, and let it in any station, for a cost as: free the first 4 hours, 1 euro the next 30 minutes, 2 euros per hour.

Unfortunatelly, the service was discontinued by August 2017.

Monuments and sights

- Cathedral of St Peter, gothic cathedral

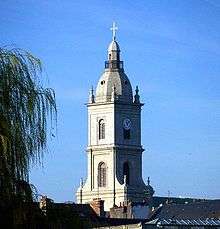

- Church of St Patern, classic church

- Chapel of Saint-Yves, baroque church

- Château Gaillard (medieval house now used as an archaeological museum)

- Musée de la Cohue (fine arts museum)

- Hôtel de Ville

- Old city walls, which include :

- Tour du Connétable (a large medieval tower part of the old city walls)

- Château de l'Hermine (former castle, transformed into a palace in the 17th century, and a residence of the Dukes of Brittany between the 13th and 16th centuries)

- Porte Calmont, medieval city gate

- Porte Prison, medieval city gate

- Porte Poterne, medieval city gate

- Porte Saint-Jean, medieval city gate

- Porte Saint-Vincent, 18th century city gate

- Many timber-framed houses in the old town

- "Vannes and his wife", a funny painted granite sculpture from the 15th century in front of Château Gaillard

- The harbour

Education

In fiction

- In the last of the Three Musketeers novels of Alexandre Dumas, The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later, published in 1847, the musketeer Aramis appears as bishop of Vannes before becoming General of the Society of Jesus.

- In Sébastien Roch, a novel by Octave Mirbeau published in 1890, Sebastien is sent to a school in Vannes, Saint-François-Xavier, where he is a victim of sexual abuse.

- In Sir Nigel, a novel by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published in 1906, Nigel is made seneschal of the Castle of Vannes after a battle in Brittany. He doesn't remain in Vannes, since after winning in another battle, the Black Prince dubs him a knight and Nigel returns to England to wed the Lady Mary.

- Jean-François Parot has written a series of crime fictions printed up to 2010 taking place in the 18th century, whose main character is Nicolas Le Floch, a Police Commissioner who was also educated in the school of Saint François-Xavier in Vannes, but he didn't share Sebastien Roch's misfortune. The Nicolas Le Floch novels have been adapted as a television series.

- In The Secret Of The Missing Boat, a children's book by Paul Berna published in 1966 as La Voile Rouge.

- In "Charlemagne and Florent," a short story by Ranylt Richildis published in 2014 by Myths Inscribed.

- Vannes is a major location in C.J. Adrien's novel The Oath of the Father, published in 2015, about the Viking raids in Brittany.

Notable people

Vannes was the birthplace of:

- Albinus of Angers (born 469), Roman Catholic saint

- Saint Emilion (Emilianus) (?-767), monk and Roman Catholic saint, he gave his name to one of the main red wine areas of Bordeaux

- Duke François I (1414–1450) of Brittany

- Louis-Marie Autissier (1772–1830), painter

- Louise Bourgoin (born 1981), actress

- Gabriel Fabre (1774–1858), general of the First French Empire

- Pierre de La Gorce (1846–1934), historian

- Paul César Helleu (1859–1927), painter

- Émile Jourdan (1860–1931), painter of Pont-Aven School

- Delly (alias Frédéric Petitjean de la Rosière) (1876–1949), novel writer with his sister Jeanne-Marie

- Alain de Goué (1879–1918), historian

- Alphonse Barbé (1885–1983), journalist and anarchist

- Louis Martin-Chauffier (1894–1980), writer, journalist and member of the French Resistance

- Yves Rocard (1903–1992), physicist

- Colonel Remy (alias Gilbert Renault) (1904–1984), secret agent of the French Resistance

- Alain Resnais (1922-2014), film director

- Jean Vezin (1933–), palaeographer

- Yves Coppens (born 1934), paleontologist

- Serge Latouche (born 1940), economist

- Jacques Ramouillet (born 1941), mountaineer

- Cédric Morgan (born 1943), writer, winner of the Prix Breizh in 2015

- Claude-Michel Schönberg, (born 1944), singer and songwriter

- Bernard Poignant (born 1945), French politician

- Hélène de Fougerolles (born 1973), actress

- Mathieu Berson (born 1980), footballer

- Joris Marveaux footballer

- Sylvain Marveaux footballer

- Yann Kermorgant footballer

Sport

The local football team is Vannes OC, members of the Championnat de France de Ligue 2 for the 2009-10 season.

The Rugby Club Vannes is the rugby union team and competed in Pro D2 for the 2015-16 season.

Both teams play at the Stade de la Rabine built in 2001.

The town was the start line for stage 9 of the 2015 Tour de France

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Vannes is twinned with:

| Town | Region | Country |

Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mons | Wallonia | 1952 | |

| Cuxhaven | Lower Saxony | 1963 | |

| Hampshire | 1967 |

Vannes also has partnerships (‘partenariats’) with:

See also

- Saint-Vincent Gate (Vannes)

- Veneti (Gaul)

- Saint Meriasek

- Operation Dingson

- Communes of the Morbihan department

- Pierre Marie François Ogé Sculpture in Vannes town hall.

- Eleanor, a Nile Crocodile resident of the Aquarium du Vannes.

Gallery

Panorama of the old town

Panorama of the old town In the old town centre

In the old town centre Place des Lices

Place des Lices Old washing-places

Old washing-places Château de l'Hermine

Château de l'Hermine Port de Vannes

Port de Vannes Garden of the Château de l'Hermine

Garden of the Château de l'Hermine Street in town center

Street in town center

St. Patern church

St. Patern church The port, at the foot of St. Vincent gate

The port, at the foot of St. Vincent gate

References

- Notes

- ↑ History of Vannes Official website of the city

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry (2008). Britain and the continent: networks of interaction. A Companion to Roman Britain. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–11.

- ↑ Balter, Michael. "DNA recovered from underwater British site may rewrite history of farming in Europe". Science News. Science. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry (2008). Britain and the continent: networks of interaction." A Companion to Roman Britain. John Wiley & Sons. p. 528. ISBN 9780470998854. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ (in French) Ofis ar Brezhoneg: Enseignement bilingue

- ↑ "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vannes. |

- (in French) Official web site of the city

- (in French) French Ministry of Culture list for Vannes