Sioux

| Očhéthi Šakówiŋ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 170,110[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

US: (SD, MN, NE, MT, ND, IA, WI, IL, WY) Canada: (MB, SK) | |

| Languages | |

| Sioux language (Lakota, Western Dakota, Eastern Dakota), Assiniboine, Stoney, English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (incl. syncretistic forms), traditional religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Assiniboine, Dakota, Lakota, Nakoda (Stoney), and other Siouan-speaking peoples |

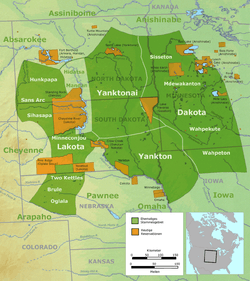

The Sioux (/suː/), also known as Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations peoples in North America. The term can refer to any ethnic group within the Great Sioux Nation or to any of the nation's many language dialects. The Sioux comprise three major divisions based on language divisions: the Dakota, Lakota and Nakota.

The Santee Dakota (Isáŋyathi; "Knife") reside in the extreme east of the Dakotas, Minnesota and northern Iowa. The Yankton and Yanktonai Dakota (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ and Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna; "Village-at-the-end" and "Little village-at-the-end"), collectively also referred to by the endonym Wičhíyena, reside in the Minnesota River area. They are considered to be the middle Sioux, and have in the past been erroneously classified as Nakota.[2] The actual Nakota are the Assiniboine and Stoney of Western Canada and Montana. The Lakota, also called Teton (Thítȟuŋwaŋ; possibly "Dwellers on the prairie"), are the westernmost Sioux, known for their hunting and warrior culture.

Today, the Sioux maintain many separate tribal governments scattered across several reservations, communities, and reserves in North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Minnesota, and Montana in the United States; and Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan, and Alberta in Canada.

Names

The name "Sioux" was adopted in English by the 1760s from French. It is abbreviated from Nadouessioux, first attested by Jean Nicolet in 1640.[3] The name is sometimes said to be derived from an Ojibwe exonym for the Sioux meaning "little snakes" (compare nadowe "big snakes", used for the Iroquois).[4] The spelling in -x is due to the French plural marker.[5] The Proto-Algonquian form *na·towe·wa, meaning "Northern Iroquoian", has reflexes in several daughter languages that refer to a small rattlesnake (massasauga, Sistrurus).[6] An alternative explanation is derivation from an (Algonquian) exonym na·towe·ssiw (plural na·towe·ssiwak), from a verb *-a·towe· meaning "to speak a foreign language".[5] The current Ojibwe term for the Sioux and related groups is Bwaanag (singular Bwaan), meaning "roasters".[7][8] Presumably, this refers to the style of cooking the Sioux used in the past.

Some of the tribes have formally or informally adopted traditional names: the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is also known as the Sičháŋǧu Oyáte, and the Oglala often use the name Oglála Lakȟóta Oyáte, rather than the English "Oglala Sioux Tribe" or OST. The alternative English spelling of Ogallala is considered improper.[3]

The historical Sioux referred to the Great Sioux Nation as the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (pronounced [oˈtʃʰetʰi ʃaˈkowĩ]), meaning "Seven Council Fires". Each fire was a symbol of an oyate (people or nation). The seven nations that comprise the Sioux are: Bdewákaŋthuŋwaŋ (Mdewakanton), Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ (Wahpeton), Waȟpékhute (Wahpekute), Sisíthuŋwaŋ (Sisseton), the Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ (Yankton), Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna (Yanktonai), and the Thítȟuŋwaŋ (Teton or Lakota).[3] The Seven Council Fires would assemble each summer to hold council, renew kinships, decide tribal matters, and participate in the Sun Dance.[9] The seven divisions would select four leaders known as Wičháša Yatápika from among the leaders of each division.[9] Being one of the four leaders was considered the highest honor for a leader; however, the annual gathering meant the majority of tribal administration was cared for by the usual leaders of each division. The last meeting of the Seven Council Fires was in 1850.[9]

Today the Teton, Santee (mixture of the four Dakota tribes) and the Minnesota Dakota, and Yankton/Yanktonai are usually known, respectively, as the Lakota, Eastern Dakota, or Western Dakota.[3][10] In any of the three main dialects, Lakota or Dakota translate to mean "friend" or "ally", referring to the alliance that once bound the Great Sioux Nation.

History

First contact with Europeans

The Dakota are first recorded to have resided at the source of the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes during the seventeenth century.[11] They were dispersed west in 1659 due to warfare with the Iroquois. By 1700 the Dakota Sioux were living in Wisconsin and Minnesota, at this time they exterminated the Wicosawan, another Siouan people in 1710. A split of branch known as the Lakota had migrated to present-day South Dakota.[12] Late in the 17th century, the Dakota entered into an alliance with French merchants.[13] The French were trying to gain advantage in the struggle for the North American fur trade against the English, who had recently established the Hudson's Bay Company.

Relationship with French traders

The first recorded encounter between the Sioux and the French occurred when Radisson and Groseilliers reached what is now Wisconsin during the winter of 1659–60. Later visiting French traders and missionaries included Claude-Jean Allouez, Daniel Greysolon Duluth, and Pierre-Charles Le Sueur who wintered with Dakota bands in early 1700.[14] In 1736 a group of Sioux killed Jean Baptiste de La Vérendrye and twenty other men on an island in Lake of the Woods.[15] However, trade with the French continued until the French gave up North America in 1763.

Relationship with Pawnees

Author and historian Mark van de Logt wrote: "Although military historians tend to reserve the concept of "total war" for conflicts between modern industrial nations, the term nevertheless most closely approaches the state of affairs between the Pawnees and the Sioux and Cheyennes. Both sides directed their actions not solely against warrior-combatants but against the people as a whole. Noncombatants were legitimate targets. ... It is within this context that the military service of the Pawnee Scouts must be viewed."[16]

The battle of Massacre Canyon on August 5, 1873, was the last major battle between the Pawnee and the Sioux.[17]

Dakota War of 1862

By 1862, shortly after a failed crop the year before and a winter starvation, the federal payment was late. The local traders would not issue any more credit to the Santee and one trader, Andrew Myrick, went so far as to say, "If they're hungry, let them eat grass."[18] On August 17, 1862 the Dakota War began when a few Santee men murdered a white farmer and most of his family. They inspired further attacks on white settlements along the Minnesota River. The Santee attacked the trading post. Later, settlers found Myrick among the dead with his mouth stuffed full of grass.[19]

On November 5, 1862 in Minnesota, in courts-martial, 303 Santee Sioux were found guilty of rape and murder of hundreds of American settlers. They were sentenced to be hanged. No attorneys or witnesses were allowed as a defense for the accused, and many were convicted in less than five minutes of court time with the judge.[20] President Abraham Lincoln commuted the death sentences of 284 of the warriors, while signing off on the hanging of 38 Santee men on December 26, 1862 in Mankato, Minnesota. It was the largest mass-execution in U.S. history, on US soil.[21]

Afterwards, the US suspended treaty annuities to the Dakota for four years and awarded the money to the white victims and their families. The men remanded by order of President Lincoln were sent to a prison in Iowa, where more than half died.[20]

During and after the revolt, many Santee and their kin fled Minnesota and Eastern Dakota to Canada, or settled in the James River Valley in a short-lived reservation before being forced to move to Crow Creek Reservation on the east bank of the Missouri.[20] A few joined the Yanktonai and moved further west to join with the Lakota bands to continue their struggle against the United States military.[20]

Others were able to remain in Minnesota and the east, in small reservations existing into the 21st century, including Sisseton-Wahpeton, Flandreau, and Devils Lake (Spirit Lake or Fort Totten) Reservations in the Dakotas. Some ended up in Nebraska, where the Santee Sioux Reservation today has a reservation on the south bank of the Missouri.

Those who fled to Canada now have descendants residing on nine small Dakota Reserves, five of which are located in Manitoba (Sioux Valley, Long Plain, Dakota Tipi, Birdtail Creek, and Oak Lake [Pipestone]) and the remaining four (Standing Buffalo, Moose Woods [White Cap], Round Plain [Wahpeton], and Wood Mountain) in Saskatchewan.

Red Cloud's War

Red Cloud's War (also referred to as the Bozeman War) was an armed conflict between the Lakota and the United States Army in the Wyoming Territory and the Montana Territory from 1866 to 1868. The war was fought over control of the Powder River Country in north central Wyoming.

The war is named after Red Cloud, a prominent Sioux chief who led the war against the United States following encroachment into the area by the U.S. military. The war ended with the Treaty of Fort Laramie. The Sioux victory in the war led to their temporarily preserving their control of the Powder River country.[22]

Great Sioux War of 1876

The Great Sioux War of 1876 comprised a series of battles between the Lakota and allied tribes such as the Cheyenne against the United States military. The earliest engagement was the Battle of Powder River, and the final battle was the Wolf Mountain. Included are the Battle of the Rosebud, Battle of the Little Bighorn, Battle of Warbonnet Creek, Battle of Slim Buttes, Battle of Cedar Creek, and the Dull Knife Fight. The Great Sioux War of 1876–77 was also known as the Black Hills War, and was centered on the Lakota tribes of the Sioux, although several natives believe that the primary target of the United States military was the Northern Cheyenne tribe. The series of battles occurred in Montana territory, Dakota territory, and Wyoming territory, and resulted in a victory for the United States military.

Wounded Knee Massacre

The massacre at Wounded Knee Creek was the last major armed conflict between the Lakota and the United States. It was described as a "massacre" by General Nelson A. Miles in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs.[23]

On December 29, 1890, five hundred troops of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, supported by four Hotchkiss guns (a lightweight artillery piece capable of rapid fire), surrounded an encampment of the Lakota bands of the Miniconjou and Hunkpapa[24] with orders to escort them to the railroad for transport to Omaha, Nebraska.

By the time it was over, 25 troopers and more than 150 Lakota Sioux lay dead, including men, women, and children. It remains unknown which side was responsible for the first shot; some of the soldiers are believed to have been the victims of "friendly fire" because the shooting took place at point-blank range in chaotic conditions.[25] Around 150 Lakota are believed to have fled the chaos, many of whom may have died from hypothermia.[26]

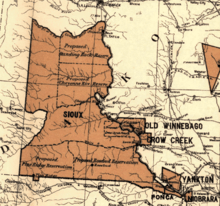

Reservations and reserves

In the late 19th century, railroads wanted to build tracks through Indian lands. The railroad companies hired hunters to exterminate the bison herds, the Plains Indians' primary food supply. The Dakota and Lakota were forced to accept US-defined reservations in exchange for the rest of their lands and farming and ranching of domestic cattle, as opposed to a nomadic, hunting economy. During the first years of the Reservation Era, the Sioux people depended upon annual federal payments guaranteed by treaty for survival.

In Minnesota, the treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota in 1851 left the Dakota with a reservation 20 miles (32 km) wide on each side of the Minnesota River.

Today, half of all enrolled Sioux in the United States live off reservation. Enrolled members in any of the Sioux tribes in the United States are required to have ancestry that is at least 1/4 degree Sioux (the equivalent to one grandparent).[27]

In Canada, the Canadian government recognizes the tribal community as First Nations. The land holdings of these First Nations are called Indian reserves.

Modern reservations, reserves, and communities

- Reserves shared with other First Nations

20th century activism

Wounded Knee incident

The Wounded Knee incident began February 27, 1973 when the town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota was seized by followers of the American Indian Movement. The occupiers controlled the town for 71 days while various state and federal law enforcement agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the United States Marshals Service laid siege. Two members of A.I.M. were killed by gunfire during the incident.

Republic of Lakotah

The Lakota Freedom Delegation, a group of controversial Native American activists, declared on December 19, 2007 the Lakota were withdrawing from all treaties signed with the United States to regain sovereignty over their nation. One of the activists, Russell Means, claimed that the action is legal and cites natural, international and US law.[28] The group considers Lakota to be a sovereign nation, although as yet the state is generally unrecognized. The proposed borders reclaim thousands of square kilometres of North and South Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska and Montana.[29]

Current activism

The Lakota made national news when NPR's "Lost Children, Shattered Families investigative story aired. It exposed what many critics consider to be the "kidnapping" of Lakota children from their homes by the state of South Dakota's Department of Social Services (D.S.S.). Lakota activists such as Madonna Thunder Hawk and Chase Iron Eyes, along with the People's Law Project, have alleged that Lakota grandmothers are illegally denied the right to foster their own grandchildren. They are currently working to redirect federal funding away from the state of South Dakota's D.S.S. to new tribal foster care programs. This would be a historic shift away from the state's traditional control over Lakota foster children.

Protest against the Dakota Access oil pipeline

In the summer of 2016, Sioux Indians and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe began a protest against construction of the Dakota Access oil pipeline, also known as the Bakken pipeline, which, if completed, is designed to carry hydrofracked crude oil from the Bakken oil fields of North Dakota to the oil storage and transfer hub of Patoka, Illinois.[30] The pipeline travels only half a mile north of the Standing Rock Sioux reservation and is designed to pass underneath the Missouri River and upstream of the reservation, causing many concerns over the tribe's drinking water safety, environmental protection, and harmful impacts on culture.[31][32] The pipeline company claims that the pipeline will provide jobs, reduce American dependence on foreign oil and reduce the price of gas.[33]

The conflict sparked a nationwide debate and much news media coverage. Thousands of indigenous and non-indigenous supporters joined the protest, and several camp sites were set up south of the construction zone. The protest was peaceful, and alcohol, drugs and firearms were not allowed at the campsite or the protest site.[34] On August 23, Standing Rock Sioux Tribe released a list of 87 tribal governments who wrote resolutions, proclamations and letters of support stating their solidarity with Standing Rock and the Sioux people.[35] Since then, many more Native American organizations, environmental groups and civil rights groups have joined the effort in North Dakota, including the Black Lives Matter movement, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, the 2016 Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein and her running mate Ajamu Baraka, and many more.[36] The Washington Post called it a "National movement for Native Americans."[37]

Political organization

The historical political organization was based on individual participation and the cooperation of many to sustain the tribe's way of life. Leaders were chosen based upon noble birth and demonstrations of chiefly virtues, such as bravery, fortitude, generosity, and wisdom.[9]

- Political leaders were members of the Načá Omníčiye society and decided matters of tribal hunts, camp movements, whether to make war or peace with their neighbors, or any other community action.[38]

- Societies were similar to fraternities; men joined to raise their position in the tribe. Societies were composed of smaller clans and varied in number among the seven divisions.[9] There were two types of societies: Akíčhita, for the younger men, and Načá, for elders and former leaders.[9]

- Akíčhita (Warrior) societies existed to train warriors, hunters, and to police the community.[38] There were many smaller Akíčhita societies, including the Kit-Fox, Strong Heart, Elk, and so on.[38]

- Leaders in the Načá societies, per Načá Omníčiye, were the tribal elders and leaders. They elected seven to ten men, depending on the division, each referred to as Wičháša Itȟáŋčhaŋ ("chief man"). Each Wičháša Itȟáŋčhaŋ interpreted and enforced the decisions of the Načá.[38]

- The Wičháša Itȟáŋčhaŋ would elect two to four Shirt Wearers, who were the voice of the society. They settled quarrels among families and also foreign nations.[9] Shirt Wearers were often young men from families with hereditary claims of leadership. However, men with obscure parents who displayed outstanding leaderships skills and had earned the respect of the community might also be elected. Crazy Horse is an example of a common-born "Shirt Wearer".[9]

- A Wakíčhuŋza ("Pipe Holder") ranked below the "Shirt Wearers". The Pipe Holders regulated peace ceremonies, selected camp locations, and supervised the Akíčhita societies during buffalo hunts.[38]

Religion

The Sioux tribe, like many North American tribal religions, "were performative, oral, and variable within each community as each generation drew upon its tradition in order to create its own religious forms, derived from experience".[39] "Aboriginal Indian Religions, North of Mexico, were locally produced modes of relationships between communities of associated individuals and their ultimate sources of life... wind, sun, thunderers, animals, corn, etc".[39] Sioux Nation religious beliefs revolve around the Wakan Tanka, which is synonymous with the Great Spirit. Two of their central religious ceremonies are the Sun Dance and the Ghost Dance.[40] The Sioux Nation was one of the few Native American peoples who practiced the Sun Dance and the Ghost Dance.

Linguistics

The Sioux comprise three closely related language groups:

- Eastern Dakota (also known as Santee-Sisseton or Dakhóta)

- Santee (Isáŋyáthi: Bdewákhathuŋwaŋ, Waȟpékhute)

- Sisseton (Sisíthuŋwaŋ, Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ)

- Western Dakota (or Yankton-Yanktonai or Dakȟóta)

- Yankton (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ)

- Yanktonai (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna)

- Lakota (or Lakȟóta, Teton, Teton Sioux)

The earlier linguistic three-way division of the Sioux language identified Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota as dialects of a single language, where Lakota = Teton, Dakota = Santee-Sisseton and Nakota = Yankton-Yanktonai.[6] However, the latest studies[10][41] show that Yankton-Yanktonai never used the autonym Nakhóta, but pronounced their name roughly the same as the Santee (i.e. Dakȟóta).

These later studies identify Assiniboine and Stoney as two separate languages, with Sioux being the third language. Sioux has three similar dialects: Lakota, Western Dakota (Yankton-Yanktonai) and Eastern Dakota (Santee-Sisseton). Assiniboine and Stoney speakers refer to themselves as Nakhóta or Nakhóda[10] (cf. Nakota).

The term Dakota has also been applied by anthropologists and governmental departments to refer to all Sioux groups, resulting in names such as Teton Dakota, Santee Dakota, etc. This was mainly because of the misrepresented translation of the Ottawa word from which Sioux is derived.[9]

Music

Modern geographic divisions

The Sioux maintain many separate tribal governments scattered across several reservations and communities in North America: in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Montana in the United States; and in Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan and Alberta in Canada.

The earliest known European record of the Sioux identified them in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin.[6] After the introduction of the horse in the early 18th century, the Sioux dominated larger areas of land—from present day Central Canada to the Platte River, from Minnesota to the Yellowstone River, including the Powder River country.[38]

Santee (Isáŋyathi or Eastern Dakota)

The Santee migrated north and westward from the Southeastern United States, first into Ohio, then to Minnesota. Some came up from the Santee River and Lake Marion, area of South Carolina. The Santee River was named after them, and some of their ancestors' ancient earthwork mounds have survived along the portion of the dammed-up river that forms Lake Marion. In the past, they were a Woodland people who thrived on hunting, fishing and farming.

Migrations of Ojibwe from the east in the 17th and 18th centuries, with muskets supplied by the French and British, pushed the Dakota further into Minnesota and west and southward. The US gave the name "Dakota Territory" to the northern expanse west of the Mississippi River and up to its headwaters.[6]

Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ-Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna (Yankton-Yanktonai or Western Dakota)

The Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ-Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna, also known by the anglicized spelling Yankton (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ: "End village") and Yanktonai (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna: "Little end village") divisions consist of two bands or two of the seven council fires. According to Nasunatanka and Matononpa in 1880, the Yanktonai are divided into two sub-groups known as the Upper Yanktonai and the Lower Yanktonai (Hunkpatina).[6]

They were involved in quarrying pipestone. The Yankton-Yanktonai moved into northern Minnesota. In the 18th century, they were recorded as living in the Mankato region of Minnesota.[42]

Lakota (Teton or Thítȟuŋwaŋ)

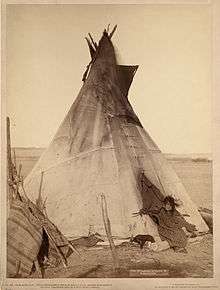

The Sioux likely obtained horses sometime during the seventeenth century (although some historians date the arrival of horses in South Dakota to 1720, and credit the Cheyenne with introducing horse culture to the Lakota). The Teton (Lakota) division of the Sioux emerged as a result of this introduction. Dominating the northern Great Plains with their light cavalry, the western Sioux quickly expanded their territory further to the Rocky Mountains (which they call Heska, "white mountains"). The Lakota once subsisted on the bison hunt, and on corn. They acquired corn mostly through trade with the eastern Sioux and their linguistic cousins, the Mandan and Hidatsa along the Missouri River.[6] The name Teton or Thítȟuŋwaŋ is archaic among the people, who prefer to call themselves Lakȟóta.[10]

Ethnic divisions

The Sioux are divided into three ethnic groups, the larger of which are divided into sub-groups, and further branched into bands.

- The Santee live on reservations, reserves, and communities in Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Canada. However, after the Dakota war of 1862 many Santee were sent to Crow Creek Indian Reservation and in 1864 some from the Crow Creek Reservation were sent to the Santee Sioux Reservation.

- Most of the Yanktons live on the Yankton Indian Reservation in southeastern South Dakota. Some Yankton live on the Lower Brule Indian Reservation and Crow Creek Indian Reservation. The Yanktonai are divided into Lower Yanktonai, who occupy the Crow Creek Reservation; and Upper Yanktonai, who live in the northern part of Standing Rock Indian Reservation, on the Spirit Lake Tribe in central North Dakota, and in the eastern half of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeastern Montana. In addition, they reside at several Canadian reserves, including Birdtail, Oak Lake, and Moose Woods.[10]

- The Lakota are the westernmost of the three groups, occupying lands in both North and South Dakota.

Today, many Sioux also live outside their reservations.

- Santee division (Eastern Dakota) (Isáŋyathi)[10]

- Mdewakantonwan (Bdewékhaŋthuŋwaŋ "Spirit Lake Village")[10]

- notable persons: Little Crow

- Sisseton (Sisíthuŋwaŋ, perhaps meaning "Fishing Grounds Village")

- Wahpekute (Waȟpékhute, "Leaf Archers")[10]

- notable persons: Inkpaduta

- Wahpetonwan (Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ, "Leaf Village")[10]

- Mdewakantonwan (Bdewékhaŋthuŋwaŋ "Spirit Lake Village")[10]

- Yankton-Yanktonai division (Western Dakota) (Wičhíyena)

- Teton division (Lakota) (Thítȟuŋwaŋ,[10] perhaps meaning "Dwellers on the Prairie"):

- Oglála (perhaps meaning "Those Who Scatter Their Own")

- notable persons: Crazy Horse, Red Cloud, Black Elk, Blue Horse, Iron Tail, Flying Hawk and Billy Mills (Olympian)

- Hunkpapa (Húŋkpapȟa,[10] meaning "Those who Camp by the Door" or "Wanderers")

- notable persons: Sitting Bull

- Sihasapa (Sihásapa, "Blackfoot Sioux,"[10] not to be confused with the Algonquian-speaking Piegan Blackfeet)

- Miniconjou (Mnikȟówožu, "Those who Plant by Water")[10]

- notable persons: Lone Horn, Touch the Clouds

- Brulé (French translation of Sičháŋǧu, "Burned Thigh")[10]

- Sans Arc (French translation of Itázipčho, "Those Without Bows")[10]

- Two Kettles (Oóhenupa, "Two Boilings")[10]

- Oglála (perhaps meaning "Those Who Scatter Their Own")

In popular media

- The Richard Harris film A Man Called Horse and its two sequels are fictional accounts of Sioux people

- The HBO movie Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee depicts the relocation and reservations of the people from the Sioux perspective, based on the book by Dee Brown.

- The films Dances with Wolves and Thunderheart contain fictional depictions of the Sioux People.

- The game "Age of Empires III: The WarChiefs" employs the Sioux as a playable civilization.

Notable Sioux

Historical

- Šóta (Old Chief Smoke) — an original Oglala Lakota head chief

- Siŋté Glešká (Spotted Tail) — Brulé chief who resisted joining Red Cloud's War

- Thaóyate Dúta (Little Crow/His Red Nation) — Mdewakanton Dakota chief and warrior

- Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake (Sitting Bull) — Famous Hunkpapa Lakota chief and holy man

- Tȟašúŋke Witkó (Crazy Horse) — Famous Oglala Lakota warrior

- Maȟpíya Ičáȟtagye (Touch the Clouds) – Minneconjou Lakota chief and warrior

- Maȟpíya Lúta (Red Cloud) — Famous Oglala Lakota chief and spokesperson

- Heȟáka Sápa (Black Elk) — Famous Oglala Lakota medicine and holy man

- Ité Omáǧažu (Rain-in-the-Face) — Hunkpapa Lakota war chief

- Tȟáȟča Hušté (Lame Deer) — Mineconju Lakota holy man and spiritual preserver

- Wí Sápa (Black Moon) — Miniconjou Lakota chief

- Matȟó Héȟloǧeča (Hollow Horn Bear) — Sicangu (Brulé) Lakota leader

- Phizí (Gall) — Hunkpapa Lakota war chief

- Ógle Lúta (Red Shirt) — Oglala Lakota warrior and chief

- Inkpáduta (Scarlet Point/Red End) — Wahpekute Dakota war chief

- Waŋbdí Tháŋka (Big Eagle) — Mdewakanton Dakota chief

- Tamaha (One Eye/Standing Moose) — Mdewekanton Dakota chief

- Óta Kté (Luther Standing Bear/Plenty Kill) — Oglala Lakota writer and actor

- Núŋp Kaȟpá (Two Strike) — Sicangu Lakota chief

- Čhetáŋ Sápa (Black Hawk) — Itázipčho Lakota ledger artist

- Tȟatȟóka Íŋyaŋke (Running Antelope) — Hunkpapa Lakota chief

- Matȟó Watȟákpe (John Grass/Charging Bear) — Sihasapa Lakota chief

- Tȟatȟáŋka Ská (White Bull) — Miniconjou Lakota warrior and nephew of Sitting Bull

- Waŋblí Kté (Kill Eagle) — Sihasapa Lakota warrior and leader

- Šúŋkawakȟáŋ Tȟó (Blue Horse) — Oglala chief, warrior, educator and statesman

- Matȟó Wayúhi (Conquering Bear) — Sičháŋǧu Lakota chief

- Čhetáŋ Kiŋyáŋ (Flying Hawk) — Oglala Lakota chief, philosopher, and historian

- Matȟó Wanáȟtake (Kicking Bear) — Oglala born Miniconjou Lakota warrior and chief

- Uŋpȟáŋ Glešká (Spotted Elk/Big Foot) — Miniconjou Lakota chief

- Hé Waŋžíča (Lone Horn) — Miniconjou Lakota chief

- Kȟaŋǧí Yátapi (Crow King/Medicine Bag That Burns) — Hunkpapa Lakota war chief

- Wičháša Tȟáŋkala (Little Big Man/Charging Bear) — Oglala Lakota Warrior

- Šúŋka Khúčiyela (Low Dog) — Oglala Lakota chief and warrior

- Wašíčuŋ Tȟašúŋke (American Horse) ("The Younger") — Oglala Lakota Chief

- Wašíčuŋ Tȟašúŋke (American Horse) ("The Elder") — Oglala Lakota Chief

- Tȟašúŋke Kȟokípȟapi (Young Man Afraid Of His Horses) — Oglala Lakota Chief

- Ištáȟba (Sleepy Eye) — Sisseton Dakota chief

- Ohíyes’a (Charles Eastman) — Author, physician and reformer

- Colonel Gregory "Pappy" Boyington — World War II Fighter Ace and Medal of Honor recipient; 1/4 Sioux

- Charging Thunder (1877–1929), Blackfoot Sioux chief who was part of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in 1903, but remained in England when the show returned to America. He married Josephine, an American horse trainer who had just given birth to their first child, Bessie, and together they settled in Darwen, before moving to Gorton. His name became George Edward Williams, after registering with the British immigration authorities to enable him to find work. Williams ended up working at the Belle Vue Zoo as an elephant keeper. He died from pneumonia on July 28, 1929. His interment was at Gorton's cemetery.

- Óta Kté (Luther Standing Bear) — Author, educator, philosopher and actor

- Ziŋtkála-Šá (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin) — Author, educator, musician and political activist

Contemporary

Contemporary Sioux people are listed under the tribes to which they belong.

- Category:Sioux people

- Assiniboine people

- Lakota

By individual tribe

- Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation

- Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe of the Cheyenne River Reservation

- Crow Creek Sioux Tribe of the Crow Creek Reservation

- Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe

- Lower Brule Sioux Tribe of the Lower Brule Reservation

- Rosebud Sioux Tribe of the Rosebud Indian Reservation

- Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community

- Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate

- Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North & South Dakota

- Yankton Sioux Tribe of South Dakota

Legacy

A Manitoba Historical Plaque was erected at the Spruce Woods Provincial Park by the province to commemorate Assiniboin (Nakota) First Nation's role in Manitoba's heritage.[44]

See also

- Sault (disambiguation), pronounced like Sioux

- Soo (disambiguation), pronounced like Sioux

- Sue (disambiguation), pronounced like Sioux

References

- ↑ Norris, Tina; Vines, Paula L.; Hoeffel, Elizabeth M. (January 2012). "The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ↑ for a report on the long-established blunder of misnaming as "Nakota", the Yankton and the Yanktonai, see the article Nakota

- 1 2 3 4 5 Johnson, Michael (2000). The Tribes of the Sioux Nation. Osprey Publishing Oxford. ISBN 1-85532-878-X.

- ↑ Learn about the history of the Sioux Indians. Indians.org. Retrieved on 2012-07-08.

- 1 2 "Sioux". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Riggs, Stephen R. (1893). Dakota Grammar, Texts, and Ethnography. Washington Government Printing Office, Ross & Haines, Inc. ISBN 0-87018-052-5.

- ↑ "a Dakota". The Ojibwe People's Dictionary. University of Minnesota Board of Regents. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ Ningewance, Patricia M. (2009). Zagataagan, A Northern Ojibwe Dictionary, Anishinaabemowin Ikidowinan gaa-niibidebii'igadegin dago gaye ewemitigoozhiibii'igaadegin, Ojibwe-English Volume 2. 61 King St. Sioux Lookout ON. Canada: Kwayaciiwin Education Resource Centre. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-897579-15-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hassrick, Royal B.; Maxwell, Dorothy; Bach, Cile M. (1964). The Sioux: Life and Customs of a Warrior Society. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0607-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Ullrich, Jan (2008). New Lakota Dictionary (Incorporating the Dakota Dialects of Yankton-Yanktonai and Santee-Sisseton). Lakota Language Consortium. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-9761082-9-1.

- ↑ Hyde, George E. (1984). Red Cloud's Folk: A History of the Oglala Sioux Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-8061-1520-3.

- ↑ Johnson, Michael; Smith, Jonathan (2000). Tribes of the Sioux Nation. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 1-85532-878-X.

- ↑ van Houten, Gerry (1991). Corporate Canada An Historical Outline. Toronto: Progress Books. pp. 6–8. ISBN 0-919396-54-2.

- ↑ Gibbon, Guy E (2003). The Sioux: The Dakota and Lakota Nations. Blackwell. pp. 48–52. ISBN 1-55786-566-3.

- ↑ "Where is the real Massacre Island?". Archived from the original on 2013-06-14. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- ↑ van de Logt, Mark (2012). War Party in Blue: Pawnee Scouts in the U.S. Army. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 0806184396

- ↑ Paul, R. Eli (1998) The Nebraska Indian Wars reader, 1865–1877. University of Nebraska Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-8032-8749-6

- ↑ Dillon, Richard (1993). North American Indian Wars. City: Booksales. p. 126. ISBN 1-55521-951-9.

- ↑ Steil, Mark; Post, Tim (2002-09-26). "Let them eat grass". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- 1 2 3 4 War for the Plains. Time-Life Books. 1994. ISBN 0-8094-9445-0.

- ↑ Steil, Mark; Post, Tim (2002-09-26). "Execution and expulsion". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 2011-10-02.

- ↑

- Brown, Dee (1970). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, ch. 6. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-11979-6.

- ↑ Letter: General Nelson A. Miles to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, March 13, 1917.

- ↑ Liggett, Lorie (1998). "Wounded Knee Massacre – An Introduction". Bowling Green State University. Retrieved 2007-03-02.

- ↑ Strom, Karen (1995). "The Massacre at Wounded Knee". hanksville.org.

- ↑ Jackson, Joe (2016-10-25). Black Elk: The Life of an American Visionary. Macmillan. ISBN 9780374253301.

- ↑ "Enrollment Ordinance". tribalresourcecenter.org. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28.

- ↑ Descendants of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse break away from US, Agence France-Presse news Archived 2008-08-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Harlan, Bill (21 December 2007). "Lakota group secedes from U.S." Rapid City Journal. Archived from the original on 12 July 2009. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ↑ Healy, Jack (2016-08-23). "Occupying the Prairie: Tensions Rise as Tribes Move to Block a Pipeline". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ↑ "More Than A Year After Spill, Colorado's Gold King Mine Named Superfund Site". Retrieved 2016-09-08.

- ↑ "Pipeline Spills Oil into Yellowstone River Again". 2015-01-21. Retrieved 2016-09-08.

- ↑ "What is the benefit of the Dakota Access Pipeline? - Dakota Access Pipeline Facts". Dakota Access Pipeline Facts. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ↑ Thompson, Dave (2016-08-18). "Dakota Access Pipeline construction stopped". news.prairiepublic.org.

- ↑ "Native Nations Rally in Support of Standing Rock Sioux". Indian Country Today Media Network.com. 2016-08-23. Archived from the original on 2016-08-25. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ↑ "Arrest warrants issued for Jill Stein, running mate after N.D. protest". Retrieved 2016-09-08.

- ↑ "Showdown over oil pipeline becomes a national movement for Native Americans". Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-09-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mails, Thomas E. (1973). Dog Soldiers, Bear Men, and Buffalo Women: A Study of the Societies and Cults of the Plains Indians. Prentice-Hall, Inc. ISBN 0-13-217216-X.

- 1 2 Davis, Mary B. (1994). Native America in the Twentieth Century; an Encyclopedia. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc. p. 538. ISBN 0-8240-4846-6.

- ↑ Gill, Sam D.; Sullivan, Irene F. (1992). Dictionary of Native American Mythology. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, Inc. pp. 101, 291–292. ISBN 0-87436-621-6.

- ↑ Parks, D. R.; DeMallie, R. J. (1992). "Sioux, Assiniboine, and Stoney Dialects: a Classification". Anthropological Linguistics. 34 (1–4).

- ↑ OneRoad, Amos E.; Skinner, Alanson (2003). Being Dakota: Tales and Traditions of the Sisseton and Wahpeton. Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-87351-453-X.

- ↑ not to be confused with the Oglala thiyóšpaye bearing the same name, "Unkpatila", the most famous member of which was Crazy Horse

- ↑ Manitoba Plaque. Gov.mb.ca. Retrieved on 2012-07-08.

Further reading

- Chaky, Doreen (2014). Terrible justice: Sioux Chiefs and U.S. Soldiers on the Upper Missouri, 1854–1868. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780870624148.

- Hassrick, Royal B (1977). The Sioux: life and customs of a warrior society. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0607-7.

- Gibbon, Guy E (2003). The Sioux: the Dakota and Lakota nations. Blackwell. ISBN 1-55786-566-3.

- McLaughlin, Marie L (2010). Myths and Legends of the Sioux. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-141-80554-9.

- Hyde, George E (1993). A Sioux chronicle. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2483-0.

- Standing Bear, Luther; Brininstool, E A (2006). My People the Sioux. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9332-1.

- In the Shadow of Wounded Knee August 2012 National Geographic (magazine) with Reservation map history

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sioux. |

- "Sioux," Encyclopedia of the Great Plains

- "Sioux," Countries and Their Cultures

- Myths And Legends Of The Sioux

- Lakota Sioux – Their Lands, Allies and Enemies

- Russell Means on late Lakota (Sioux) History