Canadian cuisine

|

| Part of a series on |

| Canadian cuisine |

|---|

|

Regional cuisines |

|

Styles and dishes

|

|

Religious and ethnic |

|

Canadian cuisine varies widely depending on the regions of the nation. The three earliest cuisines of Canada have First Nations, English, Scottish and French roots, with the traditional cuisine of English Canada closely related to British cuisine, while the traditional cuisine of French Canada has evolved from French cuisine and the winter provisions of fur traders. With subsequent waves of immigration in the 19th and 20th century from Central, Southern, and Eastern Europe, South Asia, East Asia, and the Caribbean, the regional cuisines were subsequently augmented.

Definitions

Although certain dishes may be identified as "Canadian" due to the ingredients used or the origin of its inception, an overarching style of Canadian cuisine is more difficult to define. Some Canadians such as the former Canadian prime minister Joe Clark believe that Canadian cuisine is a collage of dishes from the cuisines of other cultures. Clark himself has been paraphrased to have noted: "Canada has a cuisine of cuisines. Not a stew pot, but a smorgasbord.".[1]

Some define Canadian cuisine by the foods native to North America, now used worldwide, such as squash, beans, peppers, berries, wild rice, salmon, and large claw lobster. Some define Canadian cuisine by recipes altered due to lack of ingredients of the original dish found elsewhere, such as tourtière made with pork not pigeon, sushi made with salmon not tuna, candy made with maple syrup instead of molasses. Some have sought to define Canadian cuisine along the line of how Claus Meyer defined Nordic cuisine in his Manifesto for the New Nordic Kitchen; namely that dishes in Canadian cuisine should reflect Canadian seasons, that they should use locally sourced ingredients that thrive in the Canadian climate, and that they are combined with good taste and health in mind.[2] Others believe that Canadian cuisine is still in the process of being defined from the cuisines of the numerous cultures that have influenced it, and that being a culture of many cultures, Canada and its cuisine is less about a particular dish but rather how the ingredients are combined.[2]

Aboriginal food in particular is considered very Canadian. Métis food is especially so, since the Métis people had such an integrated role in how Canada, and Canadian food, came to be. Foods such as bannock, moose, deer, bison, pemmican, maple taffy, and Métis stews such as barley stew, all originated either in Canada or through aboriginal peoples, and are eaten widely throughout the country. Other foods that originated in Canada are often thought of in the same overarching group of Canadian food as aboriginal foods, despite not being so, such as peameal bacon, cajun seasoning, and Nanaimo bars. There are also some foods of non-Canadian origin that are eaten very frequently. Perogies (a Ukrainian food) are an example of this, due to the large number of early Ukrainian immigrants. There are, however, some regional foods that are not eaten as often on one side of the country as on the other, such as dulse in the Maritimes, stews in the Territories, or poutine in the Francophone areas of Canada (not limited to Québec). In general, Canadian foods contain a lot of starch, breads, game meats (such as deer, moose, bison, etc), and often involve a lot of stews and soups, most notably Métis-style and split-pea soup.

Cultural contributions

Canadian food has been shaped and impacted by continual waves of immigration, with the types of foods and from different regions and periods of Canada reflecting this immigration.[3]

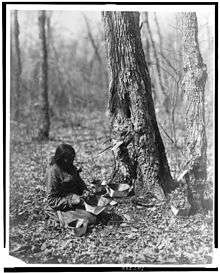

Aboriginal people

The traditional aboriginal cuisine of Canada was based on a mixture of wild game, foraged foods, and farmed agricultural products. Each region of Canada with its own First Nations and Inuit people used their local resources and own food preparation techniques for their cuisines.

Maple syrup was first collected and used by aboriginal people of Eastern Canada and North Eastern US. Canada is the world's largest producer of maple syrup.[4] The origins of maple syrup production are not clear though the first syrups were made by repeatedly freezing the collected maple sap and removing the ice to concentrate the sugar in the remaining sap.[5] Maple syrup is one of the most commonly consumed Canadian foods of Aboriginal origins.

In most of the Canadian West Coast and Pacific Northwest, Pacific salmon was an important food resource to the First Nations peoples, along with certain marine mammals. Salmon were consumed fresh when spawning or smoked dry to create a jerky-like food that could be stored year-round. The latter food is commonly known and sold as "salmon jerky". Whipped Soapberry, known as xoosum (HOO-shum, "Indian ice cream") in the Interior Salish languages of British Columbia, is consumed similarly to ice cream or as a cranberry-cocktail-like drink. It is known for being a kidney tonic, which are called agutak in Arctic Canada (with animal/fish fat).

In the Arctic, Inuit traditionally survived on a diet consisting of land and marine mammals, fish, and foraged plant products. Meats were consumed fresh but also often prepared, cached, and allowed to ferment into igunaq or kiviak. These fermented meats have the consistency and smell of certain soft aged cheeses. Snacks such as muktuk, which consist of whale skin and blubber is eaten plain, though sometimes dipped in soy sauce. Chunks of muktuk are sliced with an ulu prior to or during consumption. Fish are eaten boiled, fried, and prior to today's settlements, often in dried forms. The so-called "Eskimo potato" (Inuit: oatkuk: Claytonia tuberosa)[6] and other "mousefoods" are some of the plants consumed in the arctic.

Foods such as "bannock", popular with First Nations and Inuit, reflect the historic exchange of these cultures with French fur traders, who brought with them new ingredients and foods.[7] Common contemporary consumption of bannock, powdered milk, and bologna by aboriginal Canadians reflects the legacy of Canadian colonialism in the prohibition of hunting and fishing, and the institutional food rations provided to Indian reserves.[8] Due to similarities in treatment under colonialism, many Native American communities throughout the continent consume similar food items with some emphasis on local ingredients.

Europeans

Settlers and traders from the British Isles account for the culinary influences of early English Canada in the Maritimes and Southern Ontario (Upper Canada),[3] while French settlers account for the cuisine of southern Quebec (Lower Canada), Northeastern Ontario, and New Brunswick.[3] Southwestern regions of Ontario have strong Dutch and Scandinavian influences.

In Canada's Prairie provinces, which saw massive immigration from Eastern and Northern Europe in the pre-WW1 era, Ukrainian, German, and Polish cuisines are strong culinary influences. Also noteworthy in some areas of the British Columbia Interior and the Prairies is the cuisine of the Doukhobors, Russian-descended vegetarians.[3]

The Waterloo, Ontario, region and the southern portion of the Province of Manitoba have traditions of Mennonite and Germanic cookery.

The cuisines of Newfoundland and the Maritime provinces derive mainly from British and Irish cooking, with a preference for salt-cured fish, beef, and pork. Ontario, Manitoba and British Columbia also maintain strong British cuisine traditions.

Jewish immigrants to Canada during the late 1800s played a significant culinary role within Canada, chiefly renowned for Montreal-style bagels and Montreal-style smoked meat. A regional variation of both emerged within Winnipeg, Manitoba's Jewish community, which also derived Winnipeg-style Cheesecake from New York recipes. Winnipeg has given birth to numerous other unique dishes, such as the schmoo torte, smoked goldeye and "co-op style" rye bread and cream cheese.

East Asian

Much of what are considered "Chinese dishes" in Canada are more likely to be Canadian or North American inventions, with the Chinese restaurants of each region tailoring their traditional cuisine to local tastes.[3] This "Canadian Chinese cuisine" is widespread across the country, with great variation from place to place.

The Chinese buffet, although found in the United States and other parts of Canada, had its origins in early Gastown, Vancouver, c.1870. This serving setup came out of the practice of the many Scandinavians working in the woods and mills around the shantytown getting the Chinese cook to put out a steam table on a sideboard.

In Toronto, a style of medium-thick crust margarita pizza topped with garlic and basil oil topping is popular, which combines Italian pizza with the Vietnamese tradition of using herbed oil toppings in food.[9]

National food of Canada

Common contenders as the Canadian national food include:

According to an informal survey by The Globe and Mail conducted through Facebook from collected comments, users considered the following to be the Canadian national dish, with maple syrup likely above all the other foods if it were considered:[13]

- Poutine (51%)

- Montreal-style bagels (14%)

- Salmon jerky (dried smoked salmon) (11%)

- Perogy/Pierogi (10%)

- Ketchup chips (7%)

- Nova Scotian donair (4%)

- California roll (1%)

In another survey from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in the summer of 2012:[17]

Regional

While many ingredients are commonly found throughout Canada, each region with its own history and local population has unique ingredients, which are used to define unique dishes.

| Ingredient | Defining dish | Pacific | Mountain | The Prairies | Ontario | Quebec | Atlantic | Northern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caribou | Caribou stew | X | X | X | ||||

| Potatoes | Poutine | X | X | X | ||||

| Saskatoon berries | Saskatoon berry jam | X | X | X | ||||

| Fiddlehead ferns | Boiled fiddleheads | X | X | X | ||||

| Cloudberry | Bakeapple pie | X | X | |||||

| Maple syrup | Pancake topping | X | X | X | ||||

| Dulse | Dulse crisps | X | ||||||

| Harp seal | Flipper pie | X | X | |||||

| Sockeye | Smoked salmon | X | ||||||

| Pacific salmon | Cedar-plank salmon | X | ||||||

| Atlantic salmon | Smoked salmon | X | X | |||||

| Atlantic cod | Fish and brewis | X | X | |||||

| Lobster | Boiled lobster | X | X | |||||

| Winnipeg goldeye | Smoked goldeye | X | ||||||

| Pork | Farmer sausage | X | ||||||

| Summer savory | Dressing | X |

Wild game of all sorts is still hunted and eaten by many Canadians, though not commonly in urban centres. Venison, from white-tailed deer, moose, elk (wapiti) or caribou, is eaten across the country and is considered quite important to many First Nations cultures.[18] Seal meat is eaten, particularly in the Canadian North, the Maritimes, and Newfoundland and Labrador. Wild fowl like ducks and geese, grouse (commonly called partridge) and ptarmigan are also regularly hunted. Other animals like bear and beaver may be eaten by dedicated hunters or indigenous people, but are not generally consumed by much of the population.

West-Coast salmon varieties include Sockeye, Coho, Tyee a.k.a. Chinook or King, and Pink.

Wild chanterelle, pine, morel, lobster, puffball, and other mushrooms are commonly consumed. Canada produces good cheeses and many successful beers, and is known for its excellent ice wines and ice ciders. Gooseberries, salmonberries, pearberries, cranberries and strawberries are gathered wild or grown.

Some Canadian foods

Savoury foods

Although there are considerable overlaps between Canadian food and the rest of the cuisine in North America, many unique dishes (or versions of certain dishes) are found and available only in the country. Some are more commonly eaten than others.

| Dish | Description | Pacific | Mountain | The Prairies | Ontario | Quebec | Atlantic | Northern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calgary-style Ginger beef | Candied and deep fried beef, with sweet ginger sauce. | X | O | X | ||||

| Roast beef with Yorkshire pudding | Common Sunday dinner in English Canada, especially amongst Canadians of British ancestry | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Roast turkey | North American roast turkey | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Baked beans | Beans cooked with maple syrup | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Pig's Feet Meatball Ragout | Common ragout during Christmas time | O | ||||||

| Jiggs dinner | A Sunday meal similar to the New England boiled dinner | O | ||||||

| Back or peameal bacon | Called Canadian bacon in the US | X | X | X | O | X | ||

| Tourtière | A meat pie made of pork and lard | X | X | X | X | O | ||

| Montreal-style smoked meat | Deli style cured beef | X | X | O | X | |||

| Bannock | A fried bread and dough food | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Bouilli | Québécois beef and vegetable potroast | O | ||||||

| Bologna stew | A stew made of cubed chunks of Bologna sausage | O | ||||||

| Cod tongues and scrunchions | Baked cod tongue and deep fried pork fat | O | ||||||

| Yellow pea soup | Split pea soup eaten by settlers such as the Habitant | X | O | X | ||||

| Poutine | A dish of fries topped with cheese curds and gravy | X | X | X | X | O | X | X |

| Montreal-style bagels | A sweet, firm, wood-fired bagel | X | O | |||||

| Pemmican | Ground dried meat, fat, and berries | X | X | |||||

| Oka cheese | Cheese originally manufactured by Trappist monks | X | X | O | ||||

| Flipper pie | Pie made with harp seal flipper | O | ||||||

| Hot chicken sandwich | Chicken (or turkey) sandwich doused in gravy and peas | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Toutons | Fried bread from Newfoundland | O | ||||||

| Fish and brewis | Salt cod and hardtack, with pork cracklings | O | ||||||

| Rappie pie | Grated potato and meat casserole | O | ||||||

| Cretons | Pork spread containing onions and spices | X | O | |||||

| Poutine râpée | Grated Acadian stuffed potato dumpling | O | ||||||

| Nova Scotian donair | Ground beef doner kebab served with a sweet milk sauce | X | X | O | ||||

| Garlic fingers | Dough with cheese, garlic, and sometimes meat on top, similar to pizza | X | X | X | X | O | ||

| Lobster roll | Lobster meat mixed with mayonnaise and served in a toasted hot dog bun | X | X | O | ||||

| Cipaille/sea-pie | Fish and meat layered in a pie | X | O | X |

Sweets

- Beaver tails — also known as elephant ears, moose antlers or whale tails

- Bumbleberry pie — bumbleberry is a mixture of fruit, berries, and rhubarb

- Butter tarts – said to be invented in Eastern Ontario around 1915. The main ingredients for the filling include butter, sugar and eggs, but raisins and pecans are often added for additional flavour.

- Candy apple — also known by the British term "toffee apple", candied apples are far more popular than in the United States, where the caramel apple is common

- Figgy duff – a pudding from Newfoundland

- Jam busters — prairie jelly doughnuts

- Flapper pie – wafer pie in Manitoba; a custard pie popular in Western Canada

- Grandpères — dough dumplings boiled in maple syrup

- Maple syrup — especially tire d'érable sur la neige or "maple toffee", also as flavouring, for example in maple leaf cream cookies

- Matrimonial cake — date filled desserts

- Moosehunters — molasses cookies

- Nanaimo bars – most common in British Columbia

- Nougabricot — a Québécois preserve consisting of apricots, almonds, and pistachios.

- Persians — somewhat like a cross between a large cinnamon bun and a doughnut, topped with strawberry icing, unique to Thunder Bay, Ontario

- Pets de sœurs — lit. "farts of [holy] sisters"; pastry dough wrapped around a brown sugar and butter filling

- Pouding chômeur

- Sucre à la crème — Québécois sweet milk squares

- Sugar pie

Commercially prepared food and beverages

- Canadian pizza — typically includes tomato sauce, mozzarella cheese, bacon, pepperoni, and mushrooms; variations exist.[19]). The recipe is also known internationally by this name.[20] The classic preparation, however, is often referred to in the province of Quebec as pizza québécoise.[21]

- Candy

- Bridge mixture (bridge mix)

- Chocolate bars: Coffee Crisp, Mr. Big, Caramilk, Big Turk, Cherry Blossom, Crunchie, Crispy Crunch, Aero, Pal-O-Mine

- Glosette pieces (peanut, raisin, or almonds)

- Cereal

- Coffee

- Nabob Coffee

- Second Cup Coffee

- Tim Hortons

- Double Double

- Timbits

- Cows ice cream

- Honey dill sauce

- Kraft Dinner (also a proprietary eponym)

- Non-alcoholic drinks

- Bagged milk

- Brio chinotto

- Canada Dry ginger ale

- London Fog[22]

- Red Rose Tea

- Spruce beer — bière d'épinette, non-alcoholic soft drink from Quebec

- Snacks

- Ketchup, salt and vinegar, dill pickle, and "all dressed" flavoured potato chips

- Hawkins Cheezies

- Hickory Sticks

- Ringolos and Humpty Dumpty Party Mix

- Tiger tail ice cream — the once omnipresent black licorice and orange flavour ice cream popular throughout Canada

Alcohol

Straight

- Alcohol Global 94%

- Canadian beer

- Canadian whisky, "rye" whisky

- Canadian wine

- Ice cider

- Newfoundland Screech

- Yukon Jack — a Canadian liqueur made of whisky and honey

Mixes

- The Caesar, originally called the Bloody Caesar, is a cocktail made from vodka, clamato juice (clam-tomato juice), Worcestershire sauce, and Tabasco sauce, in a salt-rimmed glass (table salt or celery salt), and garnished with a stalk of celery, or more adventurously with a spoonful of horseradish or a shot of beef bouillon. The Caesar was invented in 1969 in Calgary, Alberta, by bartender Walter Chell, to mark the opening of a new restaurant, Marco's.[23]

- Caribou — a mix of red wine, maple syrup, and Canadian whisky; consumed during winter festivals in Quebec

- Maple liqueur — sold bottled as Sortilege, this drink combines Canadian whisky and maple syrup

- Moose Milk — a cream and hard liquor drink served and consumed at celebratory events of the Canadian Armed Forces

- Rye & Ginger — Canadian whisky and ginger ale

Street food

While most major cities in Canada (including Montreal, in a pilot project) offer a variety of street food, regional "specialties" are notable. While poutine is available in most of the country, it is far more common in Quebec. Similarly, sausage stands can be found across Canada, but are far more common in Ontario (often sold from mobile canteen trucks, usually referred to as "fry trucks" or "chip trucks" and the sausages "street meat") than in Vancouver or Victoria (where the "Mr. Tube Steak" franchise is notable and the term "smokies" or "smokeys" refers to Ukrainian sausage rather than frankfurters).

Montreal offers a number of specialties including shish taouk, the Montreal hot dog, and dollar falafels. Although falafel is widespread in Vancouver, pizza slices are much more popular. Vancouver also has many sushi establishments. Shawarma is quite prevalent in Ottawa, and Windsor, while Halifax offers its own unique version of the döner kebab called the donair, which features a distinctive sauce made from condensed milk, sugar, garlic and vinegar. Ice cream trucks can be seen (and often heard due to a jingle being broadcast on loudspeakers) nationwide during the summer months. Recently, the city of Toronto has encouraged street vendors from around the world to sell their food.

Meal formats

- Chinese smorgasbord (see #East Asian)

- Lumberjack's breakfast, aka logger's breakfast, aka "The Lumby" — a gargantuan breakfast of three-plus eggs; rations of ham, bacon and sausages; and several large pancakes. This was invented by hotelier J. Houston c.1870, at his Granville Hotel on Water Street in old pre-railway Gastown, Vancouver, in response to requests from his clientele for a better "feed" at the start of a long, hard day of work.[24][25]

See also

References

- ↑ Pandi, George (2008-04-05), "Let's eat Canadian, but is there really a national dish?", The Gazette (Montreal) Also published as "Canadian cuisine a smorgasbord of regional flavours"

- 1 2 Voinigescu, Eva (January 24, 2013), "What is Canadian Cuisine, Anyway?", Toronto Standard

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jacobs, Hersch (2009), "Structural Elements in Canadian Cuisine", Cuizine: The Journal of Canadian Food Cultures, 2 (1)

- ↑ "Maple Syrup." Archived 2011-09-08 at the Wayback Machine. Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Accessed July 2011.

- ↑ Koelling, Melvin R; Laing, Fred; Taylor, Fred (1996). "Chapter 2: History of Maple Syrup and Sugar Production". In Koelling, Melvin R; Heiligmann, Randall B. North American Maple Syrup Producers Manual. Bulletin. 856. Ohio State University. Archived from the original on 29 April 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ↑ merriam-webster.com Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ↑ Michael D. Blackstock. "Bannock Awareness". Government of British Columbia. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- ↑ EFRON, SARAH (July 17, 2012), "Bannock tacos, fried baloney – this is aboriginal cuisine?", The Globe and Mail

- ↑ ROTSZTAIN, DANIEL (2015-10-09). "Meet Toronto's new masters of the pizza". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2016-08-23.

- ↑ Trillin, Calvin (2009-11-23), "Canadian Journal, "Funny Food,"", The New Yorker: 68–70

- ↑ Wong, Grace (2010-10-02), Canada's national dish: 740 calories -- and worth every bite?, CNN

- ↑ Sufrin, Jon (2010-04-22), "Is poutine Canada's national food? Two arguments for, two against", Toronto Life, archived from the original on 2011-03-22

- 1 2 Allemang, John (2010-07-03), "We like our symbols rooted in the past, and in Quebec", The Globe and Mail

- ↑ Baird, Elizabeth (2009-06-30), "Does Canada Have a National Dish?", Canadian Living

- ↑ DeMONTIS, RITA (2010-06-21), "Canadians butter up to this tart", Toronto Sun

- ↑ Chapman, Sasha (September 2012). "Manufacturing Taste". The Walrus. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ↑ O'Neil, Lauren (June 28, 2012), The CBC Community chooses Canada's most iconic food, CBC

- ↑ "Answers - The Most Trusted Place for Answering Life's Questions". Answers.com.

- ↑

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-09. Retrieved 2013-04-01.

- ↑

- ↑ "Cookbook:London Fog - Wikibooks, open books for an open world". en.wikibooks.org. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ↑ "Calgary's Bloody Caesar hailed as nation's favourite cocktail". CBC News Calgary. May 13, 2009. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ From Milltown to Metropolis, Alan Morley

- ↑ Early Vancouver, J.S. Skitt Matthews

Further reading

- Driver, Elizabeth (2008), Culinary landmarks: a bibliography of Canadian cookbooks, 1825–1949, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-4790-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cuisine of Canada. |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |