Racism in the United States

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Racial segregation |

|---|

|

| Germany |

| South Africa |

| United States |

Racism in the United States has been widespread since the colonial era. Legally or socially sanctioned privileges and rights were given to white Americans but denied to all other races. European Americans (particularly affluent white Anglo-Saxon Protestants) were granted exclusive privileges in matters of education, immigration, voting rights, citizenship, land acquisition, and criminal procedure over a period of time extending from the 17th century to the 1960s. However, non-Protestant immigrants from Europe, particularly Irish people, Poles, and Italians, often suffered xenophobic exclusion and other forms of ethnicity-based discrimination in American society until the late 1800s and early 1900s. In addition, Middle Eastern American groups like Jews and Arabs have faced continuous discrimination in the United States, and as a result, some people belonging to these groups do not identify as white. East and South Asians have similarly faced racism in America.

Major racially and ethnically structured institutions include slavery, segregation, Native American reservations, Native American boarding schools, immigration and naturalization law, and internment camps.[1] Formal racial discrimination was largely banned in the mid-20th century and came to be perceived as socially and morally unacceptable. Racial politics remains a major phenomenon, and racism continues to be reflected in socioeconomic inequality.[2][3] Racial stratification continues to occur in employment, housing, education, lending, and government.

In the view of the United Nations and the U.S. Human Rights Network, "discrimination in the United States permeates all aspects of life and extends to all communities of color."[4] While the nature of the views held by average Americans have changed significantly over the past several decades, surveys by organizations such as ABC News have found that even in modern America, large sections of Americans admit to holding discriminatory viewpoints. For example, a 2007 article by ABC stated that about one in ten admitted to holding prejudices against Hispanic and Latino Americans and about one in four did so regarding Arab-Americans.[5] A 2018 YouGov/Economist poll found that 17% of Americans oppose interracial marriage, with 19% of "other" ethnic groups, 18% of blacks, 17% of whites, and 15% of Hispanics opposing.[6]

Some Americans saw the presidential candidacy of Barack Obama, and his election in 2008 as the first black president of the United States, as a sign that the nation had entered a new, post-racial era.[7][8] The populist radio host Lou Dobbs claimed in November 2009, "We are now in a 21st-century post-partisan, post-racial society."[9] Two months later, Chris Matthews, an MSNBC host, said of President Obama, "He is post-racial by all appearances. You know, I forgot he was black tonight for an hour."[10] The election of President Donald Trump has been viewed by some commentators as a racist backlash against the election of Barack Obama.[11]

During the 2010s, American society continues to experience high levels of racism and discrimination. One new phenomenon has been the rise of the "alt-right" movement: a white nationalist coalition that seeks the expulsion of sexual and racial minorities from the United States.[12] In August 2017, these groups attended a rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, intended to unify various white nationalist factions. During the rally, a white supremacist demonstrator drove his car into a group of counter-protesters, killing one person and injuring 19.[13][14] Since the mid-2010s, the Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Bureau of Investigation have considered white supremacist violence to be the leading threat of domestic terrorism in the United States.[15][16]

African Americans

Pre-Civil War

Atlantic slave trade

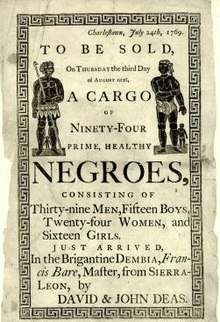

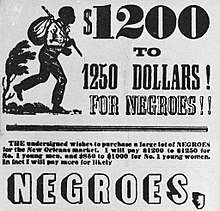

The Atlantic slave trade had an economic foundation. The dominant ideology among the European elite who structured national policy throughout the age of the Atlantic slave trade was mercantilism, the belief that national policy should be centered around amassing military power and economic wealth. Colonies were sources of mineral wealth and crops, to be used to the colonizing country's advantage.[17] Using Europeans for labor in the colonies proved unsustainably expensive, as well as harmful to the domestic labor supply of the colonizing countries. Instead, the colonies imported African slaves, who were "available in large numbers at prices that made plantation agriculture in the Americas profitable".[18]

It is also argued that along with the economic motives underlying slavery in the Americas, European world schemas played a large role in the enslavement of Africans. According to this view, the European in-group for humane behavior included the sub-continent, while African and American Indian cultures had a more localized definition of "an insider". While neither schema has inherent superiority, the technological advantage of Europeans became a resource to disseminate the conviction that underscored their schemas, that non-Europeans could be enslaved. With the capability to spread their schematic representation of the world, Europeans could impose a social contract, morally permitting three centuries of African slavery. While the disintegration of this social contract by the eighteenth century led to abolitionism, it is argued that the removal of barriers to "insider status" is a very slow process, uncompleted even today (2017).[19]

As a result of the above, the Atlantic slave trade prospered. According to estimates in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, between 1626 and 1860 more than 470,000 slaves were forcibly transported from Africa to what is now the United States.[20][21] Prior to the Civil War, eight serving presidents owned slaves, a practice protected by the U.S. Constitution.[22] Providing wealth for the white elite, approximately one Southern family in four held slaves prior to the Civil War. According to the 1860 U.S. census, there were about 385,000 slave owners out of a white population in the slave states of approximately 7 million.[23][24]

Steps toward abolition of slavery

In the early part of the 19th century, a variety of organizations were established advocating the movement of black people from the United States to locations where they would enjoy greater freedom; some endorsed colonization, while others advocated emigration. During the 1820s and 1830s the American Colonization Society (A.C.S.) was the primary vehicle for proposals to return black Americans to greater freedom and equality in Africa,[25] and in 1821 the A.C.S. established the colony of Liberia, assisting thousands of former African-American slaves and free black people (with legislated limits) to move there from the United States. The colonization effort resulted from a mixture of motives with its founder Henry Clay stating, "unconquerable prejudice resulting from their color, they never could amalgamate with the free whites of this country. It was desirable, therefore, as it respected them, and the residue of the population of the country, to drain them off".[26]

Although in 1820 the Atlantic slave trade was equated with piracy, punishable by death,[27] the practice of chattel slavery existed for the next half century. The domestic slave trade was a major economic activity in the U.S. which lasted until the 1860s.[28] Enslaved family members would be split up never to see each other again.[28] Between 1830 and 1840 nearly 250,000 slaves were taken across state lines.[28] In the 1850s more than 193,000 were transported, and historians estimate nearly one million in total took part in the forced migration.[28]

.jpg)

The historian Ira Berlin called this forced migration of slaves the "Second Middle Passage", because it reproduced many of the same horrors as the Middle Passage (the name given to the transportation of slaves from Africa to North America). These sales of slaves broke up many families, with Berlin writing that whether slaves were directly uprooted or lived in fear that they or their families would be involuntarily moved, "the massive deportation traumatized black people".[29] Individuals lost their connection to families and clans. Added to the earlier colonists combining slaves from different tribes, many ethnic Africans lost their knowledge of varying tribal origins in Africa. Most were descended from families who had been in the U.S. for many generations.[28]

All slaves in only the areas of the Confederate States of America that were not under direct control of the United States government were declared free by the Emancipation Proclamation, which was issued on January 1, 1863, by President Abraham Lincoln.[30] While personally opposed to slavery, Lincoln believed that the Constitution did not give Congress the power to end slavery, stating in his first Inaugural Address that he "had no objection to [this] being made express and irrevocable" via the Corwin Amendment.[31] On social and political rights for blacks, Lincoln stated, "I am not, nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people, I as much as any man am in favor of the superior position assigned to the white race."[32] The Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to areas loyal to, or controlled by, the Union. Slavery was not actually abolished in the U.S. until the passage of the 13th Amendment which was declared ratified on December 6, 1865.[33]

About four million black slaves were freed in 1865. Ninety-five percent of blacks lived in the South, comprising one third of the population there as opposed to one percent of the population of the North. Consequently, fears of eventual emancipation were much greater in the South than in the North.[34] Based on 1860 census figures, 8% of males aged 13 to 43 died in the civil war, including 6% in the North and 18% in the South.[35]

Reconstruction Era to World War II

Reconstruction Era

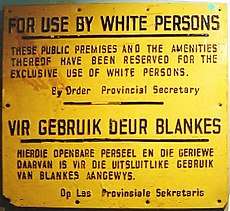

After the Civil War, the 13th amendment in 1865, formally abolishing slavery, was ratified. Furthermore, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which broadened a range of civil rights to all persons born in the United States. Despite this, the emergence of "Black Codes", sanctioned acts of subjugation against blacks, continued to bar African-Americans from due civil rights. The Naturalization Act of 1790 limited U.S. citizenship to whites only, and in 1868 the effort toward civil rights was underscored with the 14th amendment which granted citizenship to blacks.[37] The Civil Rights Act of 1875 followed, which was eliminated in a decision that undermined federal power to thwart private racial discrimination.[38] Nonetheless, the last of the Reconstruction Era amendments, the 15th amendment promised voting rights to African-American men (previously only white men of property could vote), and these cumulative federal efforts, African-Americans began taking advantage of enfranchisement. African-Americans began voting, seeking office positions, utilizing public education. Yet by the end of Reconstruction in the mid 1870s, violent white supremacists came to power via paramilitary groups such as the Red Shirts and the White League and imposed Jim Crow laws that deprived African-Americans of voting rights and instituted systemic discriminatory policies through policies of unequal racial segregation.[39] Segregation, which began with slavery, continued with Jim Crow laws, with signs used to show blacks where they could legally walk, talk, drink, rest, or eat.[40] For those places that were racially mixed, non-whites had to wait until all white customers were dealt with.[40] Segregated facilities extended from white only schools to white only graveyards.[41]

Post-Reconstruction Era

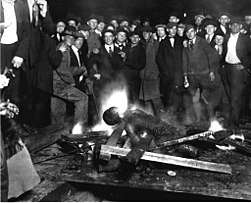

The new century saw a hardening of institutionalized racism and legal discrimination against citizens of African descent in the United States. Throughout this post Civil War period, racial stratification was informally and systemically enforced, in order to solidify the pre-existing social order. Although technically able to vote, poll taxes, pervasive acts of terror such as lynching in the United States (often perpetrated by groups such as the reborn Ku Klux Klan, founded in the Reconstruction South), and discriminatory laws such as grandfather clauses kept black Americans (and many Poor Whites) disenfranchised particularly in the South. Furthermore, discrimination extended to state legislation that "allocated vastly unequal financial support" for black and white schools. In addition to this, county officials sometimes redistributed resources earmarked for blacks to white schools, further undermining educational opportunities.[43] In response to de jure racism, protest and lobbyist groups emerged, most notably, the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) in 1909.[44]

This time period is sometimes referred to as the nadir of American race relations because racism, segregation, racial discrimination, and expressions of white supremacy all increased. So did anti-black violence, including race riots such as the Atlanta Race riot of 1906 and the Tulsa race riot of 1921. The Atlanta riot was characterized by the French newspaper Le Petit Journal as a "racial massacre of negroes".[45] The Charleston News and Courier wrote in response to the Atlanta riots: "Separation of the races is the only radical solution of the negro problem in this country. There is nothing new about it. It was the Almighty who established the bounds of the habitation of the races. The negroes were brought here by compulsion; they should be induced to leave here by persuasion."[46]

The Great Migration

In addition, racism which had been viewed primarily as a problem in the Southern states, burst onto the national consciousness following the Great Migration, the relocation of millions of African Americans from their roots in the Southern states to the industrial centers of the North after World War I, particularly in cities such as Boston, Chicago, and New York City (Harlem). Within Chicago, for example, between 1910 and 1970, the percentage of African-Americans leapt from 2.0 percent to 32.7 percent.[48] The demographic patterns of black migrants and external economic conditions are largely studied stimulants regarding the Great Migration.[49] For example, migrating blacks (between 1910 and 1920) were more likely to be literate than blacks that remained in the South. Known economic push factors played a role in migration, such as the emergence of a split labor market and agricultural distress from the boll weevil destruction of the cotton economy.[50]

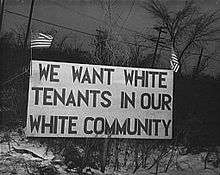

Southern migrants were often treated in accordance with pre-existing racial stratification. The rapid influx of blacks into the North disturbed the racial balance within cities, exacerbating hostility between both black and white Northerners. Stereotypic schemas of Southern blacks were used to attribute issues in urban areas, such as crime and disease, to the presence of African-Americans. Overall, African-Americans in Northern cities experienced systemic discrimination in a plethora of aspects of life. Within employment, economic opportunities for blacks were routed to the lowest-status and restrictive in potential mobility. Within the housing market, stronger discriminatory measures were used in correlation to the influx, resulting in a mix of "targeted violence, restrictive covenants, redlining and racial steering".[51]

Throughout this period, racial tensions exploded, most violently in Chicago, and lynchings—mob-directed hangings, usually racially motivated—increased dramatically in the 1920s. Urban riots—whites attacking blacks—became a northern problem.[52] Many whites defended their space with violence, intimidation, or legal tactics toward African Americans, while many other whites migrated to more racially homogeneous suburban or exurban regions, a process known as white flight.[53] Racially restrictive housing covenants were ruled unenforceable under the Fourteenth Amendment in the 1948 landmark Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer.[54]

Elected in 1912, President Woodrow Wilson ordered segregration throughout the federal government.[55] In World War I, blacks served in the United States Armed Forces in segregated units. Black soldiers were often poorly trained and equipped, and were often put on the frontlines in suicide missions. The U.S. military was still heavily segregated in World War II. The Air Force and the Marines had no blacks enlisted in their ranks. There were blacks in the Navy Seabees. In addition, no African-American would receive the Medal of Honor during the war, and black soldiers had to sometimes give up their seats in trains to the Nazi prisoners of war.[56]

World War II to Civil Rights Era

The Jim Crow Laws were state and local laws enacted in the Southern and border states of the United States and enforced between 1876 and 1965. They mandated "separate but equal" status for black Americans. In reality, this led to treatment and accommodations that were almost always inferior to those provided to white Americans. The most important laws required that public schools, public places and public transportation, like trains and buses, have separate facilities for whites and blacks. State-sponsored school segregation was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education. One of the first federal court cases to challenge segregation in schools was Mendez v. Westminster in 1946.

.jpg)

.jpg)

By the 1950s, the Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum. Membership in the NAACP increased in states across the U.S. A 1955 lynching that sparked public outrage about injustice was that of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago. Spending the summer with relatives in Money, Mississippi, Till was killed for allegedly having wolf-whistled at a white woman. Till had been badly beaten, one of his eyes was gouged out, and he was shot in the head before being thrown into the Tallahatchie River, his body weighed down with a 70-pound (32 kg) cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire. David Jackson writes that Mamie Till, Emmett's Mother, "brought him home to Chicago and insisted on an open casket. Tens of thousands filed past Till's remains, but it was the publication of the searing funeral image in Jet, with a stoic Mamie gazing at her murdered child's ravaged body, that forced the world to reckon with the brutality of American racism."[57] News photographs circulated around the country, and drew intense public reaction. The visceral response to his mother's decision to have an open-casket funeral mobilized the black community throughout the U.S.[58] Vann R. Newkirk wrote "the trial of his killers became a pageant illuminating the tyranny of white supremacy".[58] The state of Mississippi tried two defendants, but they were speedily acquitted by an all-white jury.[59]

In response to heightening discrimination and violence, non-violent acts of protest began to occur. For example, in February 1960, in Greensboro, North Carolina, four young African-American college students entered a Woolworth store and sat down at the counter but were refused service. The men had learned about non-violent protest in college, and continued to sit peacefully as whites tormented them at the counter, pouring ketchup on their heads and burning them with cigarettes. After this, many sit-ins took place in order to non-violently protest against racism and inequality. Sit-ins continued throughout the South and spread to other areas. Eventually, after many sit-ins and other non-violent protests, including marches and boycotts, places began to agree to desegregate.[60]

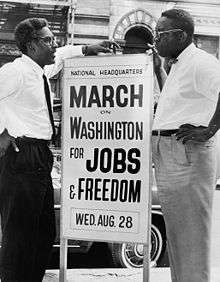

The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing marked a turning point during the Civil Rights Era. On Sunday, September 15, 1963 with a stack of dynamite hidden on an outside staircase, Ku Klux Klansmen destroyed one side of the Birmingham church. The bomb exploded in proximity to twenty-six children who were preparing for choir practice in the basement assembly room. The explosion killed four black girls, Carole Robertson (14), Cynthia Wesley (14), Denise McNair (11) and Addie Mae Collins (14).[61][62]

With the bombing occurring only a couple of weeks after Martin Luther King Jr.'s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, it became an integral aspect of transformed perceptions of conditions for blacks in America. It influenced the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (that banned discrimination in public accommodations, employment, and labor unions) and Voting Rights Act of 1965 which overruled remaining Jim Crow laws. Nonetheless, neither had been implemented by the end of the 1960s as civil rights leaders continued to strive for political and social freedom.

Many U.S. states banned interracial marriage. In 1967, Mildred Loving, a black woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, were sentenced to a year in prison in Virginia for marrying each other.[63] Their marriage violated the state's anti-miscegenation statute, the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which prohibited marriage between people classified as white and people classified as "colored" (persons of non-white ancestry).[64] In the Loving v. Virginia case in 1967, the Supreme Court invalidated laws prohibiting interracial marriage in the U.S.[65]

Segregation continued even after the demise of the Jim Crow laws. Data on house prices and attitudes toward integration suggest that in the mid-20th century, segregation was a product of collective actions taken by whites to exclude blacks from their neighborhoods.[66] Segregation also took the form of redlining, the practice of denying or increasing the cost of services, such as banking, insurance, access to jobs,[67] access to health care,[68] or even supermarkets[69] to residents in certain, often racially determined,[70] areas. Although in the U.S. informal discrimination and segregation have always existed, redlining began with the National Housing Act of 1934, which established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). The practice was fought first through passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968 (which prevents redlining when the criteria for redlining are based on race, religion, gender, familial status, disability, or ethnic origin), and later through the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, which requires banks to apply the same lending criteria in all communities.[71] Although redlining is illegal some argue that it continues to exist in other forms.

Up until the 1940s, the full revenue potential of what was called "the Negro market" was largely ignored by white-owned manufacturers in the U.S. with advertising focused on whites.[72] Blacks were also denied commercial deals. On his decision to take part in exhibition races against racehorses in order to earn money, Olympic champion Jesse Owens stated, "People say that it was degrading for an Olympic champion to run against a horse, but what was I supposed to do? I had four gold medals, but you can't eat four gold medals."[73] On the lack of opportunities, Owens added, "There was no television, no big advertising, no endorsements then. Not for a black man, anyway."[74] In the reception to honor his Olympic success Owens was not permitted to enter through the main doors of the Waldorf Astoria New York and instead forced to travel up to the event in a freight elevator.[75] The first black Academy Award recipient Hattie McDaniel was not permitted to attend the premiere of Gone with the Wind with Georgia being racially segregated, and at the Oscars ceremony in Los Angeles she was required to sit at a segregated table at the far wall of the room; the hotel had a strict no-blacks policy, but allowed McDaniel in as a favor.[76]

1980s to present

_Church_Corrected.jpg)

While substantial gains were made in the succeeding decades through middle class advancement and public employment, black poverty and lack of education continued in the context of de-industrialization.[78][79] Despite gains made after the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, some violence against black churches has also continued – 145 fires were set to churches around the South in the 1990s,[80] and a mass shooting in Charleston was perpetrated in 2015 at the historic Mother Emanuel Church.[81]

From 1981 to 1997, the United States Department of Agriculture discriminated against tens of thousands of black American farmers, denying loans that were provided to white farmers in similar circumstances. The discrimination was the subject of the Pigford v. Glickman lawsuit brought by members of the National Black Farmers Association, which resulted in two settlement agreements of $1.25 billion in 1999 and of $1.15 billion in 2009.[82]

During the 1980s and '90s a number of riots occurred that were related to longstanding racial tensions between police and minority communities. The 1980 Miami riots were catalyzed by the killing of an African-American motorist by four white Miami-Dade Police officers. They were subsequently acquitted on charges of manslaughter and evidence tampering. Similarly, the six-day 1992 Los Angeles riots erupted after the acquittal of four white LAPD officers who had been filmed beating Rodney King, an African-American motorist. Khalil Gibran Muhammad, the Director of the Harlem-based Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture has identified more than 100 instances of mass racial violence in the United States since 1935 and has noted that almost every instance was precipitated by a police incident.[83]

Politically, the "winner-take-all" structure that applies to 48 out of 50 states[84] in the electoral college benefits white representation, as no state has voters of color as the majority of the electorate.[85] This has been described as structural bias and often leads voters of color to feel politically alienated, and therefore not to vote. The lack of representation in Congress has also led to lower voter turnout.[85] As of 2016, African Americans only made up 8.7% of Congress, and Latinos 7%.[86]

Many cite the United States presidential election, 2008 as a step forward in race relations: white Americans played a role in electing Barack Obama, the country's first black president.[87] In fact, Obama received a greater percentage of the white vote (43%),[88] than did the previous Democratic candidate, John Kerry (41%).[89] Racial divisions persisted throughout the election; wide margins of Black voters gave Obama an edge during the presidential primary, where 8 out of 10 African-Americans voted for him in the primaries, and an MSNBC poll found that race was a key factor in whether a candidate was perceived as being ready for office. In South Carolina, for instance,"Whites were far likelier to name Clinton than Obama as being most qualified to be commander in chief, likeliest to unite the country and most apt to capture the White House in November. Blacks named Obama over Clinton by even stronger margins—two- and three-to one—in all three areas."[90]

Sociologist Russ Long stated in 2013 that there is now a more subtle racism that associates a specific race with a specific characteristic.[91] In a 1993 study conducted by Katz and Braly, it was presented that "blacks and whites hold a variety of stereotypes towards each other, often negative".[92] The Katz and Braley study also found that African-Americans and whites view the traits that they identify each other with as threatening, interracial communication between the two is likely to be "hesitant, reserved, and concealing".[92] Interracial communication is guided by stereotypes; stereotypes are transferred into personality and character traits which then have an effect on communication. Multiple factors go into how stereotypes are established, such as age and the setting in which they are being applied.[92] For example, in a study done by the Entman-Rojecki Index of Race and Media in 2014, 89% of black women in movies are shown swearing and exhibiting offensive behavior while only 17% of white women are portrayed in this manner.[93]

In 2012, Trayvon Martin, a seventeen-year-old teenager was fatally shot by George Zimmerman in Sanford, Florida. Zimmerman, a neighborhood-watch volunteer, claimed that Martin was being suspicious and called the Sanford police to report.[94] Between ending his call with police and their arrival, Zimmerman fatally shot Martin outside of the townhouse he was staying at. National outrage occurred when Zimmerman was not charged in the shooting. The national coverage of the incident forced Sandford leaders to arrest Zimmerman. He was charged with second-degree murder, but was found not guilty. Public outcry occurred following his release and created an abundance of mistrust between minorities and the Sanford police.

In 2014, following the Shooting of Michael Brown, the Ferguson unrest took place. In the years following, mass media has followed shootings against other innocent black men and women, often with video evidence from body-worn cameras which places officers in real time. The U.S. Justice department launched the National Center for Building Community Trust and Justice in 2014.[95] This program is center on collected data concerning racial profiling to create a change in the criminal justice program concerning implicit and explicit racial bias towards African-Americans as well as other minorities.

It is reported that in 2015, there were 315,254 African-Americans deaths.[96] Only a few gain national media attention. For example, amongst 15 high-profile cases of an African-American being shot, only 1 officer faces prison time.[97]

Asian Americans

The Naturalization Act of 1790 made Asians ineligible for citizenship, with citizenship limited to whites only.[98]

Asian Americans, including those of East Asian, Southeast Asian, and South Asian descent, have experienced racism since the first major groups of Chinese immigrants arrived in America. First-generation immigrants, children of immigrants, and Asians adopted by non-Asian families have all been impacted.[99]

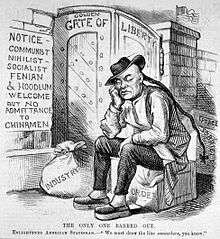

In the 19th century, America was undergoing rapid industrialization, leading to labor shortages in the mining and rail industries. Chinese immigrant labor was often used to fill this gap, most notably with the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad, leading to large-scale Chinese immigration.[99] These Chinese immigrants were despised because they took the jobs of whites for cheaper pay, and the phrase Yellow Peril, which predicted the demise of Western Civilization as a result of Chinese immigrants, gained popularity.[100] This discrimination apexed with the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned Chinese immigration to the United States. This was the first time that a law was passed to exclude a major group from the nation that was based on ethnicity and class.[99]

Local discriminatory laws were also enacted to stifle Chinese business and job opportunities; for example, in the 1886 Supreme Court case of Yick Wo v. Hopkins, a San Francisco city ordinance requiring permits for laundries (which were mostly Chinese-owned) was struck down, as it was clear the law solely targeted Chinese Americans. When the law was in effect, the city issued permits to virtually all non-Chinese permit applicants, while only granting one permit out of two hundred applications from Chinese laundry owners. When the Chinese laundries continued to operate, the city tried to fine the owners. In 1913, California, home to many Chinese immigrants, enacted an Alien Land Law, which significantly restricted land ownership by Asian immigrants, and extended it in 1920, ultimately banning virtually all land ownership by Asians.[101]

In 1907, Japanese immigrants, which were unaffected by the Exclusion Act, began to enter the United States, filling labor shortages that were once filled by Chinese workers. This influx also led to discrimination and was stymied when President Theodore Roosevelt restricted Japanese immigration. Later, Japanese immigration was closed when Japan entered into the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 to stop issuing passports to Japanese workers intending to move to the U.S.[102]

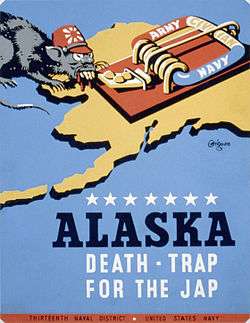

During World War II, the Republic of China was an ally of the United States, and the federal government praised the resistance of the Chinese against Japan in the Second Sino-Japanese War, attempting to reduce anti-Chinese sentiment. In 1943, the Magnuson Act was passed by Congress, repealing the Chinese Exclusion Act and reopening Chinese immigration. However, at the time, the United States was actively fighting the Empire of Japan, which was a member of the Axis powers. Anti-Japanese racism, which spiked after the attack on Pearl Harbor, was tacitly encouraged by the government, which used slurs such as "Jap" in propaganda posters and even interned Japanese Americans, citing possible security threats. Soldiers in the Pacific theater seem often dehumanized their enemy leading to American mutilation of Japanese war dead.[103] The racist nature of this dehumanization is apparent in the inconsistency of the treatment of corpses in the Pacific and the European theaters. Apparently some soldiers mailed home Japanese skulls as souvenirs, while none mailed home German or Italian skulls.[104] This prejudice continued for some time after the war, and Asian racism affected U.S. policy in the Korean and Vietnam Wars, even though Asians were on both sides of those wars as well as World War II. Some historians have alleged that a climate of racism, with unofficial rules like the "mere gook rule",[105][106] allowed for a pattern in which South Vietnamese civilians were treated as less than human and war crimes became common.[107]

Prior to 1965, Indian immigration to the U.S. was small and isolated, with fewer than fifty thousand Indian immigrants in the country. The Bellingham riots in Bellingham, Washington, on September 5, 1907, epitomized the low tolerance in the U.S. for Indians and Hindus. While anti-Asian racism was embedded in U.S. politics and culture in the early 20th century, Indians were also racialized for their anticolonialism, with U.S. officials, casting them as a Hindu menace, pushing for Western imperial expansion abroad.[108] In the 1923 case, United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, the Supreme Court ruled that high caste Hindus were not "white persons" and were therefore racially ineligible for naturalized citizenship.[109] The Court argued that the racial difference between Indians and whites was so great that the "great body of our people" would reject assimilation with Indians.[109] It was after the Luce–Celler Act of 1946 that a quota of 100 Indians per year could immigrate to the U.S. and become citizens.[110]

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 dramatically opened entry to the U.S. to immigrants other than traditional Northern European and Germanic groups, and as a result would significantly, and unintentionally, alter the demographic mix in the U.S.[111] On the U.S. immigration laws prior to 1965, sociologist Stephen Klineberg states the law "declared that Northern Europeans are a superior subspecies of the white race."[111] In 1990, Asian immigration was encouraged when nonimmigrant temporary working visas were given to help with the shortage of skilled labor within the United States.[99]

In modern times, Asians have been perceived as a "model minority". They are seen as more educated and successful, and are stereotyped as intelligent and hard-working, but socially inept.[112] Asians may experience expectations of natural intelligence and excellence from whites as well as other minorities.[101][113] This has led to discrimination in the workplace, as Asian Americans may face unreasonable expectations because of the "model minority" stereotype. In 2000, out of 1,218 adult Asian Americans, 92 percent of those who experienced personal discrimination believed that the unfair treatment was due to their ethnicity.[112]

Asian American stereotypes can also obstruct career paths; because Asians are seen as better skilled in engineering, computing, and mathematics, they are often encouraged to pursue technical careers. They are also discouraged from pursuing non-technical occupations or executive occupations requiring more social interaction, since Asians are expected to have poor social skills. In the 2000 study, forty percent of those surveyed who experienced discrimination believed that they had lost hiring or promotion opportunities. In 2007, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission reported that Asians make up 10 percent of professional jobs, while 3.7 percent of them held executive, senior level, or manager positions.[112]

Other forms of discrimination include racial profiling and hate crimes. Research shows that discrimination has led to more use of informal mental health services by Asian Americans.[114] Asian Americans who feel discriminated against also tend to smoke more.[115]

European Americans

Various European American immigrant groups have been subject to discrimination either on the basis of their immigrant status (known as "Nativism") or on the basis of their ethnicities (country of origin).

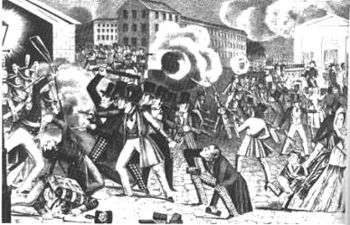

In the 19th century, this was particularly true of anti-Irish prejudice, which was partly anti-Catholic sentiment, partly anti-Irish as an ethnicity. This was especially true for Irish Catholics who immigrated to the U.S. in the mid-19th century; the large number of Irish (both Catholic and Protestant) who settled in America in the 18th century had largely (but not entirely) escaped such discrimination and eventually blended into the American white population. During the 1830s in the U.S., riots for control of job sites broke out in rural areas among rival labour teams from different parts of Ireland, and between Irish and local American work teams competing for construction jobs.[116]

The Native American Party, commonly called the Know Nothing movement was a political party, whose membership was limited to Protestant men, that operated on a national basis during the mid-1850s and sought to limit the influence of Irish Catholics and other immigrants, thus reflecting nativism and anti-Catholic sentiment. There was widespread anti-Irish job discrimination in the United States and "No Irish need apply" signs were common.[117][118][119]

The second era Ku Klux Klan was a very large nationwide organization in the 1920s, consisting of between four to six million members (15% of the nation's eligible population) that especially opposed Catholics.[120] The revival of the Klan was spurred by the release of the 1915 film The Birth of a Nation.[121] The second and third incarnations of the Ku Klux Klan made frequent references to America's "Anglo-Saxon" blood.[122] Anti-Catholic sentiment, which appeared in North America with the first Pilgrim and Puritan settlers in New England in the early 17th century, remained evident in the United States up to the presidential campaign of John F. Kennedy, who went on to become the first Catholic (and first non-Protestant) U.S. president in 1961.[123]

The 20th century saw discrimination against immigrants from southern and eastern Europe (notably Italian Americans and Polish Americans), partly from anti-Catholic sentiment (as well as discrimination against Irish Americans), and partly from Nordicism, which considered all non-Germanic immigrants as racially inferior.

Biological laws tell us that certain divergent people will not mix or blend. The Nordics propagate themselves successfully. With other races, the outcome shows deterioration on both sides.

An advocate of the U.S. immigration laws that favored Northern Europeans, the Klansman Lothrop Stoddard wrote primarily on the alleged dangers posed by "colored" peoples to white civilization, with his most famous book The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy in 1920. Nordicism led to the reduction in Southern European, along with Slavic Eastern European and Russian immigrants in the National Origins Formula of the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924, whose goal was to maintain the status quo distribution of ethnicity by limiting immigration of non-Northern Europeans. According to the U.S. Department of State the purpose of the act was "to preserve the ideal of American homogeneity".[125] The racial term Untermensch originates from the title of Stoddard's 1922 book The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Under-man.[126] It was later adopted by the Nazis (and its chief racial theorist Alfred Rosenberg) from that book's German version Der Kulturumsturz: Die Drohung des Untermenschen (1925).[127]

There was also discrimination against German Americans and Italian Americans due to Germany and Italy being enemy countries during World War I (Germany) and World War II (Germany and Italy). This resulted in a sharp decrease in German-American ethnic identity and a sharp decrease in the use of German in the United States following World War I, which had hitherto been significant, and to German American internment and Italian American internment during World War II; see also World War I anti-German sentiment.

Beginning in World War I, German Americans were sometimes accused of having political allegiances to Germany, and thus not to the United States.[128] The Justice Department attempted to prepare a list of all German aliens, counting approximately 480,000 of them, more than 4,000 of whom were imprisoned in 1917–18. The allegations included spying for Germany, or endorsing the German war effort.[129] Thousands were forced to buy war bonds to show their loyalty.[130] The Red Cross barred individuals with German last names from joining in fear of sabotage. One person was killed by a mob; in Collinsville, Illinois, German-born Robert Prager was dragged from jail as a suspected spy and lynched.[131] Questions of German American loyalty increased due to events like the German bombing of Black Tom island[132] and the U.S. entering World War I, many German Americans were arrested for refusing allegiance to the U.S.[133] War hysteria led to the removal of German names in public, names of things such as streets,[134] and businesses.[135] Schools also began to eliminate or discourage the teaching of the German language.[136] Years later during the Second World War, German Americans were once again the victims of war hysteria discrimination. Following its entry into the Second World War, the US Government interned at least 11,000 American citizens of German ancestry. The last to be released, a German-American, remained imprisoned until 1948 at Ellis Island,[137] three and a half years after the cessation of hostilities against Germany.

Specific racism against other European-American ethnicities significantly diminished as a political issue in the 1930s, being replaced by a bi-racialism of black/white, as described and predicted by Lothrop Stoddard, due to numerous causes. The National Origins Formula significantly reduced inflows of non-Nordic ethnicities; the Great Migration (of African-Americans out of the South) displaced anti-white immigrant racism with anti-black racism.[53]

Anti-Romanyism

The Roma population in America has blended more-or-less seamlessly into the rest of society. In the United States, the term "Gypsy" has come to be associated with a trade, profession, or lifestyle more than with the Romani ethnic/racial group. Some Americans, especially those self-employed in the fortune-telling and psychic reading business,[138] use the term "Gypsy" to describe themselves or their enterprise, despite having no ties to the Roma people. This can be chalked up to misperception and ignorance regarding the term rather than any bigotry or even anti-ziganism.[139]

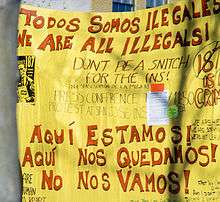

Hispanic and Latino Americans

Americans of Latin American ancestry (often categorized as "Hispanic") come from a wide variety of racial and ethnic backgrounds. Latinos are not all distinguishable as a racial minority.

After the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), the United States annexed much of the current Southwestern region from Mexico. Mexicans residing in that territory found themselves subject to discrimination. It is estimated that at least 597 Mexicans were lynched between 1848 and 1928 (this is a conservative estimate due to lack of records in many reported lynchings). Mexicans were lynched at a rate of 27.4 per 100,000 of population between 1880 and 1930. This statistic is second only to that of the African American community during the same period, which suffered an average of 37.1 per 100,000 of population.[140] Between 1848 and 1879, Mexicans were lynched at an unprecedented rate of 473 per 100,000 of population.[141]

During The Great Depression, the U.S. government sponsored a Mexican Repatriation program which was intended to encourage Mexican immigrants to voluntarily return to Mexico, however, many were forcibly removed against their will. In total, up to one million persons of Mexican ancestry were deported, approximately 60 percent of those individuals were actually U.S. citizens.

The Zoot Suit riots were vivid incidents of racial violence against Latinos (e.g., Mexican-Americans) in Los Angeles in 1943. Naval servicemen stationed in a Latino neighborhood conflicted with youth in the dense neighborhood. Frequent confrontations between small groups and individuals had intensified into several days of non-stop rioting. Large mobs of servicemen would enter civilian quarters looking to attack Mexican American youths, some of whom were wearing zoot suits, a distinctive exaggerated fashion popular among that group.[142] The disturbances continued unchecked, and even assisted, by the local police for several days before base commanders declared downtown Los Angeles and Mexican American neighborhoods off-limits to servicemen.[143]

Many public institutions, businesses, and homeowners associations had official policies to exclude Mexican Americans. School children of Mexican American descent were subject to racial segregation in the public school system. In many counties, Mexican Americans were excluded from serving as jurors in court cases, especially in those that involved a Mexican American defendant. In many areas across the Southwest, they lived in separate residential areas, due to laws and real estate company policies.[144][145][146][147]

During the 1960s, Mexican American youth formed the Chicano Civil Rights Movement.

Jewish Americans

Antisemitism has also played a role in the United States. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Jews were escaping the pogroms in Europe. They boarded boats from ports on the Baltic Sea and in Northern Germany, and largely arrived at Ellis Island, New York.[148]

It is suggested by Leo Rosten, in his book The Joys of Yiddish, that as soon as they left the boat, they were subject to racism from the port immigration authorities. The derogatory term kike was adopted when referring to Jews (because they often could not write so they may have signed their immigration papers with circles – or kikel in Yiddish).[149] Efforts were also made by the Asiatic Exclusion League to bar Jewish immigrants (along with other Middle Eastern ethnic groups, like Arabs, Assyrians, and Armenians) from naturalization, but they (along with Assyrians and Armenians) were nevertheless granted US citizenship, despite being classified as Asian.[150]

From the 1910s, the Southern Jewish communities were attacked by the Ku Klux Klan, who objected to Jewish immigration, and often used "The Jewish Banker" in their propaganda. In 1915, Leo Frank was lynched in Georgia after being convicted of rape and sentenced to death (his punishment was commuted to life imprisonment).[151] This event was a catalyst in the re-formation of the new Ku Klux Klan.[152]

The events in Nazi Germany also attracted attention from the United States. Jewish lobbying for intervention in Europe drew opposition from the isolationists, amongst whom was Father Charles Coughlin, a well known radio priest, who was known to be critical of Jews, believing that they were leading the United States into the war.[153] He preached in weekly, overtly anti-Semitic sermons and, from 1936, began publication of a newspaper, Social Justice, in which he printed anti-Semitic accusations such as The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.[154]

A number of Jewish organizations, Christian organizations, Muslim organizations, and academics consider the Nation of Islam to be anti-Semitic. Specifically, they claim that the Nation of Islam has engaged in revisionist and antisemitic interpretations of the Holocaust and exaggerates the role of Jews in the African slave trade.[155] The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) alleged that the NOI's Health Minister, Dr. Abdul Alim Muhammad, accused Jewish doctors of injecting blacks with the AIDS virus,[156] an allegation that Muhammad and The Washington Post have refuted.[157]

Although Jews are often perceived as white in the American mainstream, the relationship of Jews to whiteness remains complex, with some preferring not to identify as white.[158][159][160][161] Prominent activist and rabbi Michael Lerner argues, in a 1993 Village Voice article, that "in America, to be 'white' means to be the beneficiary of the past 500 years of European exploration and exploitation of the rest of the world" and that "Jews can only be deemed white if there is massive amnesia on the part of non-Jews about the monumental history of anti-Semitism".[161] African-American activist Cornel West, in an interview with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, has explained:

Even if some Jews do believe that they're white, I think that they've been duped. I think that antisemitism has proven itself to be a powerful force in nearly every post of Western civilization where Christianity has a presence. And so even as a Christian, I say continually to my Jewish brothers and sisters: don't believe the hype about your full scale assimilation and integration into the mainstream. It only takes an event or two for a certain kind of anti-Jewish, antisemitic sensibility to surface in places that you would be surprised. But I'm just thoroughly convinced that America is not the promised land for Jewish brothers and sisters. A lot of Jewish brothers say, "No, that's not true. We finally ..." Yeah—they said that in Alexandria. You said that in Weimar Germany.[162]

New antisemitism

In recent years some scholars have advanced the concept of New antisemitism, coming simultaneously from the Far Left, the far right, and radical Islam, which tends to focus on opposition to the creation of a Jewish homeland in the State of Israel, and argue that the language of Anti-Zionism and criticism of Israel are used to attack Jews more broadly. In this view, the proponents of the new concept believe that criticisms of Israel and Zionism are often disproportionate in degree and unique in kind, and attribute this to antisemitism.[163]

Yehuda Bauer, Professor of Holocaust Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has argued that the concept of a "new antisemitism" is essentially false since it is in fact an alternative form of the old antisemitism of previous decades, which he believes remains latent at times but recurs whenever it is triggered. In his view, the current trigger is the Israeli situation; if a compromise making ground in the Arab-Israeli peace process were achieved, he believes that antisemitism would decline but not disappear.

Noted critics of Israel, such as Noam Chomsky and Norman Finkelstein, question the extent of new antisemitism in the United States. Chomsky has written in his work Necessary Illusions that the Anti-Defamation League casts any question of pro-Israeli policy as antisemitism, conflating and muddling issues as even Zionists receive the allegation.[164] Finkelstein has stated that supposed "new antisemitism" is a preposterous concept advanced by the ADL to combat critics of Israeli policy.[165]

Middle Eastern and South Asian Americans

People of Middle Eastern and South Asian descent historically occupied an ambiguous racial status in the United States. Middle Eastern and South Asian immigrants were among those who sued in the late 19th and early 20th century to determine whether they were "white" immigrants as required by naturalization law. By 1923, courts had vindicated a "common-knowledge" standard, concluding that "scientific evidence", including the notion of a "Caucasian race" including Middle Easterners and many South Asians, was incoherent. Legal scholar John Tehranian argues that in reality this was a "performance-based" standard, relating to religious practices, education, intermarriage and a community's role in the United States.[167]

Arab Americans

Racism against Arab Americans[168] and racialized Islamophobia against Muslims has risen concomitantly with tensions between the American government and the Islamic world.[169] Following the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, discrimination and racialized violence has markedly increased against Arab Americans and many other religious and cultural groups.[170] Scholars, including Sunaina Maira and Evelyn Alsultany, argue that in the post-September 11 climate, Muslim Americans have been racialized within American society, although the markers of this racialization are cultural, political, and religious rather than phenotypic.[171][172]

Arab Americans in particular were most demonized which led to hatred towards Middle Easterners living in the United States and elsewhere in the Western world.[173][174] There have been attacks against Arabs not only on the basis of their religion (Islam), but also on the basis of their ethnicity; numerous Christian Arabs have been attacked based on their appearances.[175] In addition, other Middle Eastern peoples (Iranians, Assyrians, Armenians, Jews, Turks, Yezidis, Kurds, etc.) who are mistaken for Arabs because of perceived similarities in appearance have been collateral victims of anti-Arabism.

Non-Arab and non-Muslim Middle Eastern people, as well as South Asians of different ethnic/religious backgrounds (Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs) have been stereotyped as "Arabs". The case of Balbir Singh Sodhi, a Sikh who was murdered at a Phoenix gas station by a white supremacist for "looking like an Arab terrorist" (because of the turban that is a requirement of Sikhism), as well as that of Hindus being attacked for "being Muslims" have achieved prominence and criticism following the September 11 attacks.[176][177]

Those of Middle Eastern descent who are in the United States military sometimes face racism from fellow soldiers. Army Spc Zachari Klawonn endured numerous instances of racism during his enlistment at Fort Hood, Texas. During his basic training he was made to put cloth around his head and play the role of terrorist. His fellow soldiers had to take him down to the ground and draw guns on him. He was also called things such as "raghead", "sand monkey", and "Zachari bin Laden".[178][179]

According to a 2004 study, although official parameters encompass Arabs as part of the "white American" racial category, some Arab American adolescents do not identify as white.[180]

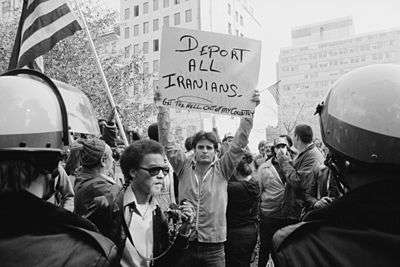

Iranian Americans

The November 1979 Iranian hostage crisis of the U.S. embassy in Tehran precipitated a wave of anti-Iranian sentiment in the United States, directed both against the new Islamic regime and Iranian nationals and immigrants. Even though such sentiments gradually declined after the release of the hostages at the start of 1981, they sometimes flare up. In response, some Iranian immigrants to the U.S. have distanced themselves from their nationality and instead identify primarily on the basis of their ethnic or religious affiliations.[181]

Since the 1980s and especially since the 1990s, it has been argued, Hollywood's depiction of Iranians has gradually shown signs of vilifying Iranians.[182] Hollywood network productions such as 24,[183] John Doe, On Wings of Eagles (1986),[184] Escape from Iran: The Canadian Caper (1981),[185] and JAG almost regularly host Persian speaking villains in their storyline.

Indian Americans

Indian Americans have sometimes been mistaken in the United States for Arab or Muslim, and thus many of the same prejudices faced by Arab Americans have been experienced by Indian Americans also, regardless of actual religious or ethnic background.

In the 1980s, a gang known as the Dotbusters specifically targeted Indian Americans in Jersey City, New Jersey with violence and harassment.[186] Studies of racial discrimination, as well as stereotyping and scapegoating of Indian Americans have been conducted in recent years.[187] In particular, racial discrimination against Indian Americans in the workplace has been correlated with Indophobia due to the rise in outsourcing/offshoring, whereby Indian Americans are blamed for US companies offshoring white-collar labor to India.[188][189] According to the offices of the Congressional Caucus on India, many Indian Americans are severely concerned of a backlash, though nothing serious has taken place yet.[189] Due to various socio-cultural reasons, implicit racial discrimination against Indian Americans largely go unreported by the Indian American community.[187]

Numerous cases of religious stereotyping of American Hindus (mainly of Indian origin) have also been documented.[190]

Since the September 11, 2001 attacks, there have been scattered incidents of Indian Americans becoming mistaken targets for hate crimes. In one example, a Sikh, Balbir Singh Sodhi, was murdered at a Phoenix gas station by a white supremacist. This happened after September 11, and the murderer claimed that his turban made him think that the victim was a Middle Eastern American. In another example, a pizza deliverer was mugged and beaten in Massachusetts for "being Muslim" though the victim pleaded with the assailants that he was in fact a Hindu.[191] In December 2012, an Indian American in New York City was pushed from behind onto the tracks at the 40th Street-Lowery Street station in Sunnyside and killed.[192] The police arrested a woman, Erika Menendez, who admitted to the act and justified it, stating that she shoved him onto the tracks because she believed he was "a Hindu or a Muslim" and she wanted to retaliate for the attacks of September 11, 2001.[193]

Native Americans

Native Americans, who have lived on the North American continent for at least 10,000 years,[194] had an enormously complex impact on American history and racial relations. During the colonial and independent periods, a long series of conflicts were waged, often with the objective of obtaining resources of Native Americans. Through wars, forced displacement (such as in the Trail of Tears), and the imposition of treaties, land was taken. The loss of land often resulted in hardships for Native Americans. In the early 18th century, the English had enslaved nearly 800 Choctaws.[195] After the creation of the United States, the idea of Indian removal gained momentum. However, some Native Americans chose or were allowed to remain and avoided removal whereafter they were subjected to official racism. The Choctaws in Mississippi described their situation in 1849, "we have had our habitations torn down and burned, our fences destroyed, cattle turned into our fields and we ourselves have been scourged, manacled, fettered and otherwise personally abused, until by such treatment some of our best men have died."[196] Joseph B. Cobb, who moved to Mississippi from Georgia, described Choctaws as having "no nobility or virtue at all," and in some respect he found blacks, especially native Africans, more interesting and admirable, the red man's superior in every way. The Choctaw and Chickasaw, the tribes he knew best, were beneath contempt, that is, even worse than black slaves.[197]

In the 1800s, conflicts were spurred by ideologies such as Manifest destiny, which held that the United States was destined to expand from coast to coast on the North American continent. In the years leading up to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 there were many armed conflicts between settlers and Native Americans.[198] A justification for the policy of conquest and subjugation of the indigenous people emanated from the stereotyped perceptions of all Native Americans as "merciless Indian savages" (as described in the United States Declaration of Independence).[199] Simon Moya-Smith, culture editor at Indian Country Today, states, "Any holiday that would refer to my people in such a repugnant, racist manner is certainly not worth celebrating. [July Fourth] is a day we celebrate our resiliency, our culture, our languages, our children and we mourn the millions – literally millions – of indigenous people who have died as a consequence of American imperialism."[200] In 1861, residents of Mankato, Minnesota, formed the Knights of the Forest, with a goal of 'eliminating all Indians from Minnesota.' An egregious attempt occurred with the California gold rush, the first two years of which saw the deaths of thousands of Native Americans. Under Mexican rule in California, Indians were subjected to de facto enslavement under a system of peonage by the white elite. While in 1850, California formally entered the Union as a free state, with respect to the issue of slavery, the practice of Indian indentured servitude was not outlawed by the California Legislature until 1863.[201] The 1864 deportation of the Navajos by the U.S. government occurred when 8,000 Navajos were forced to an internment camp in Bosque Redondo,[202] where, under armed guards, more than 3,500 Navajo and Mescalero Apache men, women, and children died from starvation and disease.[202]

Native American nations on the plains in the west continued armed conflicts with the U.S. throughout the 19th century, through what were called generally Indian Wars.[204] Notable conflicts in this period include the Dakota War, Great Sioux War, Snake War and Colorado War. In the years leading up to the Wounded Knee massacre the U.S. government had continued to seize Lakota lands. A Ghost Dance ritual on the Northern Lakota reservation at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, led to the U.S. Army's attempt to subdue the Lakota. The dance was part of a religion founded by Wovoka that told of the return of the Messiah to relieve the suffering of Native Americans and promised that if they would live righteous lives and perform the Ghost Dance properly, the European American invaders would vanish, the bison would return, and the living and the dead would be reunited in an Edenic world.[205] On December 29, 1890, at Wounded Knee, gunfire erupted, and U.S. soldiers killed up to 300 Indians, mostly old men, women and children.[206]

During the period surrounding the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre, author L. Frank Baum wrote two editorials about Native Americans. Five days after the killing of the Lakota Sioux holy man, Sitting Bull, Baum wrote, "The proud spirit of the original owners of these vast prairies inherited through centuries of fierce and bloody wars for their possession, lingered last in the bosom of Sitting Bull. With his fall the nobility of the Redskin is extinguished, and what few are left are a pack of whining curs who lick the hand that smites them. The Whites, by the law of conquest, by a justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians. Why not annihilation? Their glory has fled, their spirit broken, their manhood effaced; better that they die than live the miserable wretches that they are."[207] Following the December 29, 1890, massacre, Baum wrote, "The Pioneer has before declared that our only safety depends upon the total extermination [sic] of the Indians. Having wronged them for centuries we had better, in order to protect our civilization, follow it up by one more wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the earth. In this lies safety for our settlers and the soldiers who are under incompetent commands. Otherwise, we may expect future years to be as full of trouble with the redskins as those have been in the past."[207][208]

Military and civil resistance by Native Americans has been a constant feature of American history. So too have a variety of debates around issues of sovereignty, the upholding of treaty provisions, and the civil rights of Native Americans under U.S. law.

Reservation marginalization

Once their territories were incorporated into the United States, surviving Native Americans were denied equality before the law and often treated as wards of the state.[209]

Many Native Americans were moved to reservations—constituting 4% of U.S. territory. In a number of cases, treaties signed with Native Americans were violated. Tens of thousands of American Indians and Alaska Natives were forced to attend a residential school system which sought to reeducate them in white settler American values, culture and economy.[210][211]

The treatment of the Native Americans was admired by the Nazis.[212] Nazi expansion eastward was accompanied with invocation of America's colonial expansion westward under the banner of Manifest Destiny, with the accompanying wars on the Native Americans.[213] In 1928, Hitler praised Americans for having "gunned down the millions of Redskins to a few hundred thousand, and now kept the modest remnant under observation in a cage" in the course of founding their continental empire.[214] On Nazi Germany's expansion eastward, Hitler stated, "Our Mississippi [the line beyond which Thomas Jefferson wanted all Indians expelled] must be the Volga, and not the Niger."[213]

Further dispossession of various kinds continues into the present, although these current dispossessions, especially in terms of land, rarely make major news headlines in the country (e.g., the Lenape people's recent fiscal troubles and subsequent land grab by the State of New Jersey), and sometimes even fail to make it to headlines in the localities in which they occur. Through concessions for industries such as oil, mining and timber and through division of land from the Allotment Act forward, these concessions have raised problems of consent, exploitation of low royalty rates, environmental injustice, and gross mismanagement of funds held in trust, resulting in the loss of $10–40 billion.[215]

The Worldwatch Institute notes that 317 reservations are threatened by environmental hazards, while Western Shoshone land has been subjected to more than 1,000 nuclear explosions.[216]

Assimilation

.jpg)

The government appointed agents, like Benjamin Hawkins, to live among the Native Americans and to teach them, through example and instruction, how to live like whites.[217] America's first president, George Washington, formulated a policy to encourage the "civilizing" process.[218]

The Naturalization Act of 1790 limited citizenship to whites only. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted U.S. citizenship to all Native Americans. Prior to the passage of the act, nearly two-thirds of Native Americans were already U.S. citizens.[219] The earliest recorded date of Native Americans becoming U.S. citizens was in 1831 when the Mississippi Choctaw became citizens after the United States Legislature ratified the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. Under article XIV of that treaty, any Choctaw who elected not to move to Native American Territory could become an American citizen when he registered and if he stayed on designated lands for five years after treaty ratification.

While formal equality has been legally recognized, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders remain among the most economically disadvantaged groups in the country, and according to National mental health studies, American Indians as a group tend to suffer from high levels of alcoholism, depression and suicide.[220]

Consequences

Developmental

Using The Schedule of Racist Events (SRE), an 18-item self-report inventory that assesses the frequency of racist discrimination, Hope Landrine and Elizabeth A. Klonoff found that racist discrimination is rampant in the lives of African Americans and is strongly related to psychiatric symptoms.[221] A study on racist events in the lives of African American women found that lifetime experiences of racism were positively related to lifetime history of both physical disease and frequency of recent common colds. These relationships were largely unaccounted for by other variables. Demographic variables such as income and education were not related to experiences of racism. The results suggest that racism can be detrimental to African American's well being.[222] The physiological stress caused by racism has been documented in studies by Claude Steele, Joshua Aronson, and Steven Spencer on what they term "stereotype threat."[223] Quite similarly, another example of the psychosocial consequences of discrimination have been observed in a study sampling Mexican-origin participants in Fresno, California. It was found that perceived discrimination is correlated with depressive symptoms, especially for those less acculturated in the United States, like Mexican immigrants and migrants.[224]

Along the vein of somatic responses to discrimination, Kennedy et al. found that both measures of collective disrespect were strongly correlated with black mortality (r = 0.53 to 0.56), as well as with white mortality (r = 0.48 to 0.54). These data suggest that racism, measured as an ecologic characteristic, is associated with higher mortality in both blacks and whites.[225] Some researchers also suggest that racial segregation may lead to disparities in health and mortality. Thomas LaVeist (1989; 1993) tested the hypothesis that segregation would aid in explaining race differences in infant mortality rates across cities. Analyzing 176 large and midsized cities, LaVeist found support for the hypothesis. Since LaVeist's studies, segregation has received increased attention as a determinant of racial disparities in mortality. Studies have shown that mortality rates for male and female African Americans are lower in areas with lower levels of residential segregation. Mortality for male and female whites was not associated in either direction with residential segregation.[226]

Researchers Sharon A. Jackson, Roger T. Anderson, Norman J. Johnson and Paul D. Sorlie found that, after adjustment for family income, mortality risk increased with increasing minority residential segregation among Blacks aged 25 to 44 years and non-Blacks aged 45 to 64 years. In most age/race/gender groups, the highest and lowest mortality risks occurred in the highest and lowest categories of residential segregation, respectively. These results suggest that minority residential segregation may influence mortality risk and underscore the traditional emphasis on the social underpinnings of disease and death.[227] Rates of heart disease among African Americans are associated with the segregation patterns in the neighborhoods where they live (Fang et al. 1998). Stephanie A. Bond Huie writes that neighborhoods affect health and mortality outcomes primarily in an indirect fashion through environmental factors such as smoking, diet, exercise, stress, and access to health insurance and medical providers.[228] Moreover, segregation strongly influences premature mortality in the US.[229]

As early as 1866, the Civil Rights Act provided a remedy for intentional race discrimination in employment by private employers and state and local public employers. The Civil Rights Act of 1871 applies to public employment or employment involving state action prohibiting deprivation of rights secured by the federal constitution or federal laws through action under color of law. Title VII is the principal federal statute with regard to employment discrimination prohibiting unlawful employment discrimination by public and private employers, labor organizations, training programs and employment agencies based on race or color, religion, gender, and national origin. Title VII also prohibits retaliation against any person for opposing any practice forbidden by statute, or for making a charge, testifying, assisting, or participating in a proceeding under the statute. The Civil Rights Act of 1991 expanded the damages available in Title VII cases and granted Title VII plaintiffs the right to a jury trial. Title VII also provides that race and color discrimination against every race and color is prohibited.

Societal

Schemas and stereotypes

Media

Popular culture (songs, theater) for European American audiences in the 19th century created and perpetuated negative stereotypes of African Americans. One key symbol of racism against African Americans was the use of blackface. Directly related to this was the institution of minstrelsy. Other stereotypes of African Americans included the fat, dark-skinned "mammy" and the irrational, hypersexual male "buck".

In recent years increasing numbers of African-American activists have asserted that rap music videos commonly utilize scantily clothed African-American performers posing as thugs or pimps. The NAACP and the National Congress of Black Women also have called for the reform of images on videos and on television. Julian Bond said that in a segregated society, people get their impressions of other groups from what they see in videos and what they hear in music.[230][231][232][233]

In a similar vein, activists protested against the BET show, Hot Ghetto Mess, which satirizes the culture of working-class African-Americans. The protests resulted in the change of the television show name to We Got to Do Better.[230]

It is understood that representations of minorities in the media have the ability to reinforce or change stereotypes. For example, in one study, a collection of white subjects were primed by a comedy skit either showing a stereotypical or neutral portrayal of African-American characters. Participants were then required to read a vignette describing an incident of sexual violence, with the alleged offender either white or black, and assign a rating for perceived guilt. For those shown the stereotypical African-American character, there was a significantly higher guilt rating for black alleged offender in the subsequent vignette, in comparison to the other conditions.[234]

While schemas have an overt societal consequence, the strong development of them have lasting effect on recipients. Overall, it is found that strong in-group attitudes are correlated with academic and economic success. In a study analyzing the interaction of assimilation and racial-ethnic schemas for Hispanic youth found that strong schematic identities for Hispanic youth undermined academic achievement.[235]

Additional stereotypes attributed to minorities continue to influence societal interactions. For example, a 1993 Harvard Law Review article states that Asian-Americans are commonly viewed as submissive, as a combination of relative physical stature and Western comparisons of cultural attitudes. Furthermore, Asian-Americans are depicted as the model minority, unfair competitors, foreigners, and indistinguishable. These stereotypes can serve to dehumanize Asian-Americans and catalyze hostility and violence.[236]

Formal discrimination

Formal discrimination against minorities has been present throughout American history. Leland T. Saito, Associate Professor of Sociology and American Studies & Ethnicity at the University of Southern California, writes, "Political rights have been circumscribed by race, class and gender since the founding of the United States, when the right to vote was restricted to white men of property. Throughout the history of the United States race has been used by whites – a category that has also shifted through time – for legitimizing and creating difference and social, economic and political exclusion."[237]

Within education, a survey of black students in sixteen majority white universities found that four of five African-Americans reported some form of racial discrimination. For example, in February 1988, the University of Michigan enforced a new anti discrimination code following the distribution of fliers saying blacks "don't belong in classrooms, they belong hanging from trees". Other forms of reported discrimination were refusal to sit next to black in lecture, ignored input in class settings, and informal segregation. While the penalties are imposed, the psychological consequences of formal discrimination can still manifest. Black students, for example, reported feelings of heightened isolation and suspicion. Furthermore, studies have shown that academic performance is stunted for black students with these feelings as a result of their campus race interactions.[238]

Minority-minority racism

Minority racism is sometimes considered controversial because of theories of power in society. Some theories of racism insist that racism can only exist in the context of social power to impose it upon others.[239] Yet discrimination and racism between racially marginalized groups has been noted. For example, there has been ongoing violence between African American and Mexican American gangs, particularly in Southern California.[240][241][242][243] There have been reports of racially motivated attacks against Mexican Americans who have moved into neighborhoods occupied mostly by African Americans, and vice versa.[244][245] According to gang experts and law enforcement agents, a longstanding race war between the Mexican Mafia and the Black Guerilla Family, a rival African American prison gang, has generated such intense racial hatred among Mexican Mafia leaders, or shot callers, that they have issued a "green light" on all blacks. This amounts to a standing authorization for Latino gang members to prove their mettle by terrorizing or even murdering any blacks sighted in a neighborhood claimed by a gang loyal to the Mexican Mafia.[246] There have been several significant riots in California prisons where Mexican American inmates and African Americans have targeted each other particularly, based on racial reasons.[247][248]