Economy of Indonesia

The Sudirman Central Business District in Jakarta, the financial capital of Indonesia | |

| Currency |

Rupiah (IDR) = 0.000069 USD 1 rupiah = 100 sen |

|---|---|

| 1 January – 31 December | |

Trade organizations | APEC, WTO, G-20, IOR-ARC, RCEP, others |

| Statistics | |

| GDP |

$1.015 trillion (nominal; 2017)[1] $3.242 trillion (PPP; 2017)[1] |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

4.9% (2015), 5.% (2016), 5.1% (2017e), 5.2% (2018f) [2] |

GDP per capita |

$3,876 (nominal; 2017)[1] $12,378 (PPP; 2017)[1] |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector | agriculture: 13.9%, industry: 40.3%, services: 45.9% (2017 est.) |

| 4% (2017 est.) | |

Population below poverty line | 10.9% (2016)[3] |

|

| |

|

| |

Labour force | 126.1 million (2017 est.) |

Labour force by occupation | Agriculture: 32%, industry: 21%, services: 47% (2016 est.) |

| Unemployment | 5.4% (2017 est.)[6] |

Main industries | petroleum and natural gas, textiles, automotive, electrical appliances, apparel, footwear, mining, cement, medical instruments and appliances, handicrafts, chemical fertilizers, plywood, rubber, processed food, jewelry, and tourism |

| 72nd (2018)[7] | |

| External | |

| Exports |

|

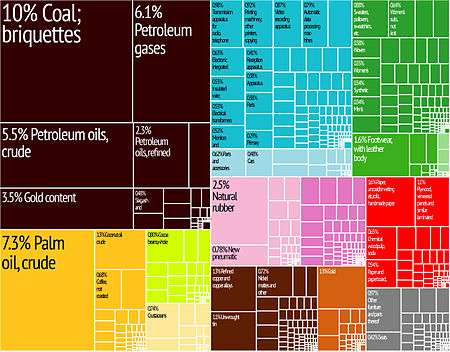

Export goods | Oil and gas, cement, food, electrical appliances, construction, plywood, textiles, rubber |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports |

|

Import goods | machinery and equipment, chemicals, fuels, foodstuffs |

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock | $247.7 billion (2017)[11] |

Gross external debt | $352.2 billion (31 December 2017est.) |

| Public finances | |

|

| |

| Revenues | $173.6 billion (2017 est.) |

| Expenses | $213.3 billion (2017 est.) |

Foreign reserves | $131.98 billion (December 2017)[16] |

Indonesia has the largest economy in Southeast Asia and is one of the emerging market economies of the world. The country is also a member of G-20 major economies and classified as a newly industrialised country.[17] It is the sixteenth largest economy in the world by nominal GDP and is the seventh largest in terms of GDP (PPP). Its GDP per capita however ranks below the world average. Indonesia still depends on domestic market and government budget spending and its ownership of state-owned enterprises (the central government owns 141 enterprises). The administration of prices of a range of basic goods (including rice and electricity) also plays a significant role in Indonesia's market economy. However, since the 1990s, the majority of the economy has been controlled by private Indonesians and foreign companies.[18][19][20]

In the aftermath of the financial and economic crisis that began in mid-1997 the government took custody of a significant portion of private sector assets through acquisition of nonperforming bank loans and corporate assets through the debt restructuring process and the companies in custody were sold for privatization several years later. Since 1999 the economy has recovered and growth has accelerated to over 4–6% in recent years.[21]

In 2012 Indonesia replaced India as the second-fastest-growing G-20 economy, behind China. Since then the annual growth rate slowed down and stagnates at the rate of 5%.[22]

History

Sukarno era

In the years immediately following the declaration of independence, both the Japanese occupation and conflict between Dutch and Republican forces had crippled the country's production, with exports of commodities such as rubber and oil being reduced to 12 and 5 percent their pre-WW2 levels, respectively.[23] The first Republican government-controlled bank, Bank Negara Indonesia (Indonesian State Bank) or BNI, was founded on July 5, 1946 and initially acted as the manufacturer and distributor of ORI (Oeang Republik Indonesia/Money of the Republic of Indonesia), a currency issued by the Republican Government which was the predecessor of Rupiah.[24] Despite so, currency issued during the Japanese occupation and by Dutch authorities were still in circulation, and simplicity of the ORI made its counterfeiting straightforward, worsening matters.[25] Once the nation's independence has been recognized by the Netherlands on December 1949, the next 10 years saw the devaluation of Dutch banknotes into half their value (Gunting Sjafruddin),[26] dissolution of the United States of Indonesia in August 1950, and during the liberal democracy period the nationalization of De Javasche Bank into modern Bank Indonesia[27] and the takeover of Dutch corporate assets following the West New Guinea dispute.[28]

During the guided democracy era in the 1960s, the economy deteriorated drastically as a result of political instability. The government was inexperienced in implementing macro-economic policies, which resulted in severe poverty and hunger. By the time of Sukarno's downfall in the mid-1960s, the economy was in chaos with 1,000% annual inflation, shrinking export revenues, crumbling infrastructure, factories operating at minimal capacity, and negligible investment. Nevertheless, Indonesia´s post-1960 economic improvement was quite remarkable when one considers how few indigenous Indonesians in the 1950s had received a formal education under Dutch colonial policies.[29]

New Order

Following President Sukarno's downfall the New Order administration brought a degree of discipline to economic policy that quickly brought inflation down, stabilised the currency, rescheduled foreign debt, and attracted foreign aid and investment. (See Inter-Governmental Group on Indonesia and Berkeley Mafia). Indonesia was until recently Southeast Asia's only member of OPEC, and the 1970s oil price raises provided an export revenue windfall that contributed to sustained high economic growth rates, averaging over 7% from 1968 to 1981.[30]

High levels of regulation and a dependence on declining oil prices, growth slowed to an average of 4.5% per annum between 1981 and 1988. A range of economic reforms were introduced in the late 1980s including a managed devaluation of the rupiah to improve export competitiveness, and de-regulation of the financial sector,[31] Foreign investment flowed into Indonesia, particularly into the rapidly developing export-oriented manufacturing sector, and from 1989 to 1997, the Indonesian economy grew by an average of over 7%.[32][33] GDP per capita grew 545% from 1970 to 1980 as a result of the sudden increase in oil export revenues from 1973 to 1979.[34]

High levels of economic growth from 1987 to 1997 masked a number of structural weaknesses in Indonesia's economy. Growth came at a high cost in terms of weak and corrupt governmental institutions, severe public indebtedness through mismanagement of the financial sector, the rapid depletion of Indonesia's natural resources, and a culture of favors and corruption in the business elite.[35]

Corruption particularly gained momentum in the 1990s, reaching to the highest levels of the political hierarchy as Suharto became the most corrupt leader according to Transparency International's corrupt leaders list.[36][37] As a result, the legal system was very weak, and there was no effective way to enforce contracts, collect debts, or sue for bankruptcy. Banking practices were very unsophisticated, with collateral-based lending the norm and widespread violation of prudential regulations, including limits on connected lending. Non-tariff barriers, rent-seeking by state-owned enterprises, domestic subsidies, barriers to domestic trade and export restrictions all created economic distortions.

1997 Asian financial crisis

The Asian financial crisis that began to affect Indonesia in mid-1997 became an economic and political crisis. Indonesia's initial response was to float the rupiah, raise key domestic interest rates, and tighten fiscal policy. In October 1997, Indonesia and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reached agreement on an economic reform program aimed at macroeconomic stabilisation and elimination of some of the country's most damaging economic policies, such as the National Car Program and the clove monopoly, both involving family members of President Soeharto. The rupiah remained weak, however, and President Soeharto was forced to resign in May 1998 after massive riots erupted. In August 1998, Indonesia and the IMF agreed on an Extended Fund Facility (EFF) under President B. J. Habibie that included significant structural reform targets. President Abdurrahman Wahid took office in October 1999, and Indonesia and the IMF signed another EFF in January 2000. The new program also has a range of economic, structural reform, and governance targets.

The effects of the financial and economic crisis were severe. By November 1997, rapid currency depreciation had seen public debt reach US$ 60 billion, imposing severe strains on the government's budget.[38] In 1998, real GDP contracted by 13.1%. The economy reached its low point in mid-1999 and real GDP growth for the year was 0.8%. Inflation reached 72% in 1998 but slowed to 2% in 1999.

The rupiah, which had been in the Rp 2,600/USD1 range at the start of August 1997 fell to 11,000/USD1 by January 1998, with spot rates around 15,000 for brief periods during the first half of 1998.[39] It returned to 8,000/USD1 range at the end of 1998 and has generally traded in the Rp 8,000–10,000/USD1 range ever since, with fluctuations that are relatively predictable and gradual. However, the rupiah began devaluing past 11,000 in 2013 and as of November 2016 is around 13,000 USD.[40]

Post-Suharto era

| Share of world GDP (PPP)[41] | |

|---|---|

| Year | Share |

| 1980 | 1.40% |

| 1990 | 1.89% |

| 2000 | 1.92% |

| 2010 | 2.24% |

| 2017 | 2.55% |

_banknotes.png)

Since an inflation target was introduced in 2000, the GDP deflator and the CPI have grown at an average annual pace of 10¾% and 9%, respectively, similar to the pace recorded in the two decades prior to the 1997 crisis, but well below the pace in the 1960s and 1970s.[42] Inflation has also generally trended lower through the 2000s, with some of the fluctuations in inflation reflecting government policy initiatives such as the changes in fiscal subsidies in 2005 and 2008, which caused large temporary spikes in CPI growth.[43]

In late 2004 Indonesia faced an 'economic mini-crisis' due to international oil prices rises and imports. The currency exhange rate reached Rp 12,000/USD1 before stabilising. Under President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, the government was forced to cut its massive fuel subsidies, which were planned to cost $14 billion for 2005, in October.[44] This led to a more than doubling in the price of consumer fuels, resulting in double-digit inflation. The situation had stabilised, but the economy continued to struggle with inflation at 17% in late 2005.

For 2006, Indonesia's economic outlook was more positive. Economic growth accelerated to 5.1% in 2004 and reached 5.6% in 2005. Real per capita income has reached fiscal year 1996/1997 levels. Growth was driven primarily by domestic consumption, which accounts for roughly three-fourths of Indonesia's gross domestic product. The Jakarta Stock Exchange was the best performing market in Asia in 2004 up by 42%. Problems that continue to put a drag on growth include low foreign investment levels, bureaucratic red tape, and very widespread corruption which causes 51.43 trillion Rupiah or 5.6573 billion US Dollar or approximately 1.4% of GDP to be lost on a yearly basis.[45] However, there is very strong economic optimism due to the conclusion of peaceful elections during the year 2004.

The unemployment rate (in February 2007) was 9.75%.[46] Despite a slowing global economy, Indonesia's economic growth accelerated to a ten-year high of 6.3% in 2007. This growth rate was sufficient to reduce poverty from 17.8% to 16.6% based on the Government's poverty line and reversed the recent trend towards jobless growth, with unemployment falling to 8.46% in February 2008.[47][48] Unlike many of its more export-dependent neighbours, it has managed to skirt the recession, helped by strong domestic demand (which makes up about two-thirds of the economy) and a government fiscal stimulus package of about 1.4% of GDP, announced earlier this year. After India and China, Indonesia is currently the third fastest growing economy in the Group of Twenty (G20) industrialised and developing economies. The $512 billion economy expanded 4.4% in the first quarter from a year earlier and last month, the IMF revised its 2009 forecast for the country to 3–4% from 2.5%. Indonesia enjoyed stronger fundamentals with the authorities implemented wide-ranging economic and financial reforms, including a rapid reduction in public and external debt, strengthening of corporate and banking sector balance sheets and reducing bank vulnerabilities through higher capitalisation and better supervision.[49]

In 2012, Indonesia's real GDP growth reached 6%, then it steadily decreased below 5% until 2015. After Yudhoyono was succeeded by Jokowi, the government took measures to ease regulations for foreign direct investments to stimulate the economy.[50] Indonesia managed to increased its GDP growth slightly above 5% in 2016–2017.[51] However the government is currently still facing problems such as the weakening currency, decreasing exports and stagnating consumer spending.[52][53] The current unemployment rate of Indonesia for 2017 is at 5.5%.[54]

Investment

Since the late 1980s, Indonesia has made significant changes to its regulatory framework to encourage economic growth. This growth was financed largely from private investment, both foreign and domestic. US investors dominated the oil and gas sector and undertook some of Indonesia's largest mining projects. In addition, the presence of US banks, manufacturers, and service providers expanded, especially after the industrial and financial sector reforms of the 1980s. Other major foreign investors included India, Japan, the United Kingdom, Singapore, the Netherlands, Qatar, Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea.

The economic crisis made continued private financing imperative but problematic. New foreign investment approvals fell by almost two-thirds between 1997 and 1999. The crisis further highlighted areas where additional reform was needed. Frequently cited areas for improving the investment climate were establishment of a functioning legal and judicial system, adherence to competitive processes, and adoption of internationally acceptable accounting and disclosure standards. Despite improvements in the laws in recent years, Indonesia's intellectual property rights regime remains weak; lack of effective enforcement is a major concern.

Under Suharto, Indonesia had moved toward private provision of public infrastructure, including electric power, toll roads, and telecommunications. The financial crisis brought to light serious weaknesses in the process of dispute resolution, however, particularly in the area of private infrastructure projects. Although Indonesia continued to have the advantages of a large labour force, abundant natural resources and modern infrastructure, private investment in new projects largely ceased during the crisis.

As of 28 June 2010, the Indonesia Stock Exchange had 341 listed companies with a combined market capitalisation of $269.9 billion.[55] As at November 2010, two-thirds of the market capitalisation was in the form of foreign funds and only around 1% of the Indonesian population have stock investments.[56] Efforts are further being made to improve the business and investment environment. Within the World Bank's Doing Business Survey,[57] Indonesia rose to 122 out of 178 countries in 2010, from 129 in the previous year. Despite these efforts, the rank is still below regional peers and an unfavourable investment climate persists. For example, potential foreign investors and their executive staff cannot maintain their own bank accounts in Indonesia, unless they are tax-paying local residents (paying tax in Indonesia for their worldwide income).

From 1990 to 2010, Indonesian companies have been involved in 3,757 mergers and acquisitions as either acquiror or target with a total known value of $137bn.[58] In 2010, 609 transactions have been announced which is a new record. Numbers had increased by 19% compared to 2009. The value of deals in 2010 was 17 bil. USD which is the second highest number ever. In the entire year of 2012, Indonesia realised total investments $32.5 billion, surpassing its annual target $25 billion, Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM) reported on 22 January. The primary investments were in the mining, transport and chemicals sectors.[59]

In 2011, the Indonesian government announced a new Masterplan (known as the MP3EI, or Masterplan Percepatan dan Perluasan Pembangunan Ekonomi Indonesia, the Masterplan to Accelerate and Expand Economic Development in Indonesia). The aim of the Masterplan was to encourage increased investment, particularly in infrastructure projects across Indonesia.[60]

Investment Grade

Indonesia regained its investment grade rating from Fitch Rating in late 2011, and from Moody's Rating in early 2012, after losing its investment grade rating in December 1997 at the onset of the Asian financial crisis, during which Indonesia spent more than Rp450 trillion ($50 billion) to bail out lenders from banks. Fitch raised Indonesia's long-term and local currency debt rating to BBB- from BB+ with both ratings is stable. Fitch also predicted that economy will grow at least 6.0% on average per year through 2013, despite a less conducive global economic climate. Moody's raised Indonesia's foreign and local currency bond ratings to Baa3 from Ba1 with a stable outlook.[61]

On May 2017 S&P Global raised Indonesia's investment grade from BB+ to BBB- with a stable outlook, due to Indonesia's economy experienced rebound in exports and strong consumer spending during the early 2017.[62]

Economic relations with other countries

China

Trade with China has increased in the beginning of 1990s, and in 2014 China became Indonesia's second largest export destination after Japan.[63] With China's economic rise, Indonesia has been intensifying its trade relationship with China to counterbalance its ties with Western countries.[64]

Japan

Japan is Indonesia's main export partner. The two countries signed the Indonesia-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (IJEPA), which had come into effect on 1 July 2008. The agreement was Indonesia’s first bilateral free-trade agreement to ease the cross-border flow of goods and people as well as investment between both countries.[65]

United States

At the beginning of the New Order, US exports to Indonesia in 1999 totalled $2.0 billion, down significantly from $4.5 billion in 1997. The main exports were construction equipment, machinery, aviation parts, chemicals, and agricultural products. US imports from Indonesia in 1999 totalled $9.5 billion and consisted primarily of clothing, machinery and transportation equipment, petroleum, natural rubber, and footwear. Economic assistance to Indonesia is coordinated through the Consultative Group on Indonesia (CGI), formed in 1989. It includes 19 donor countries and 13 international organisations that meet annually to co-ordinate donor assistance.

Macro-economic trend

This is a chart of trend of gross domestic product of Indonesia at market prices[66] by the IMF with figures in millions of rupiah.

| Year | GDP | USD exchange (rupiah) | Inflation

rate (%) |

Nominal GDP per capita (as % of US) | GDP PPP per capita (as % of US) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 60,143.191 | 627 | 18.0 | 5.25 | 5.93 |

| 1985 | 112,969.792 | 1,111 | 4.7 | 3.47 | 5.98 |

| 1990 | 233,013.290 | 1,843 | 7.8 | 3.01 | 6.63 |

| 1995 | 502,249.558 | 2,249 | 9.4 | 4.11 | 8.14 |

| 2000 | 1,389,769.700 | 8,396 | 3.8 | 2.32 | 6.92 |

| 2005 | 2,678,664.096 | 9,705 | 10.5 | 3.10 | 7.51 |

| 2010 | 6,422,918.230 | 8,555 | 5.1 | 6.38 | 9.05 |

| 2015 | 11,531,700,000 | 13,824 | 6.4 | 4.75 | 19.63 |

For purchasing power parity comparisons, the exchange rate for 1 US dollar is set at 3,094.57 rupiah.

Average net wage in Indonesia is varied by sector. In February 2017 the electricity, gas, and water sector is the sector with the highest average net wage, while the agriculture sector is the lowest.[67]

Inflation

At the end of 2017, Indonesia's inflation rate was 3.61 percent, above the government-set forecast of 3.0–3.5 percent.[68]

Economy by sector

Structure of the Indonesian economy, as per 2006 data

| Sector | Subsector | Output 2006

(Rp trillion) |

Growth since 2003

(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, etc. | Food crops | 223 | 35 |

| Estate crops | 63 | 34 | |

| Livestock, etc. | 51 | 27 | |

| Forestry | 30 | 63 | |

| Fisheries | 73 | 60 | |

| Mining | Oil and gas | 188 | 97 |

| Non oil and gas | 131 | 145 | |

| Quarrying | 36 | 87 | |

| Oil and gas manufacturing | Petroleum refining | 120 | 139 |

| Natural gas | 54 | 94 | |

| Quarrying | 213 | 35 | |

| Non oil and gas manufacturing | Food, tobacco, beverages | 213 | 38 |

| Textiles, footwear, etc. | 91 | 34 | |

| Wood, wood products | 44 | 48 | |

| Paper, printing | 40 | 43 | |

| Fertilisers, chemicals, rubber | 96 | 68 | |

| Cement, non-metallic quarry | 29 | 50 | |

| Iron, steel, basic metals | 20 | 52 | |

| Transport equipment, machinery | 222 | 87 | |

| Other manufacturing | 7 | 67 | |

| Electricity, gas, water | Electricity | 21 | 51 |

| Gas | 5 | 119 | |

| Water supply | 4 | 43 | |

| Construction & building | Construction, building | 249 | 98 |

| Trade, hotels, restaurants | Trade, wholesale and retail | 387 | 48 |

| Hotels | 17 | 52 | |

| Restaurants | 92 | 45 | |

| Transport | Road | 81 | 106 |

| Sea | 16 | 43 | |

| Rivers, ferries | 5 | 54 | |

| Air transport | 15 | 96 | |

| Other | 2 | 49 | |

| Communication | Communications | 88 | 123 |

| Finance, real estate, business | Banking | 98 | 31 |

| Non-bank finance | 27 | 87 | |

| Associated services | 2 | 82 | |

| Real estate | 98 | 72 | |

| Business services | 47 | 71 | |

| Public sector services | Government, defense | 104 | 63 |

| Private sector services | Social services, community services | 60 | 92 |

| Amusement, recreation | 10 | 46 | |

| Personal, household services | 100 | 69 |

Source: Indonesian Statistics Bureau (Biro Pusat Statistik), annual production data.

Agriculture, livestock, forestry and fishery

Agriculture is a key sector which contributed to 14.43 percent of nation's GDP.[69] Currently there are around 30 percent of Indonesian land area that is used for agriculture purpose, and employed around 49 million Indonesians (41% of total Indonesian work force).[70] Indonesia's important agricultural commodities are palm oil, natural rubber, cocoa, coffee, tea, cassava, rice and tropical spices.[70] Indonesia's main agriculture commodities are rice, cassava (tapioca), peanuts, rubber, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, copra; poultry, beef, pork, and eggs. Palm oil production is important to the economy as Indonesia is the world's biggest producer and consumer of the commodity, providing about half of the world's supply.[71] Plantations in the country stretch across 6 million hectares as of 2007,[72] with a replanting plan set for an additional 4.7 million to boost productivity in 2017.[73] As of 2012, Indonesia produces 35% of the world's certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO).[74]

Hydrocarbons

Indonesia was the only Asian member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) outside of the Middle East until 2008, and is currently a net oil importer. In 1999, Crude and condensate output averaged 1.5 million barrels (240,000 m3) per day, and in the 1998 calendar year the oil and gas sector, including refining, contributed approximately 9% to GDP. As of 2005, Indonesian crude oil and condensate output was 1.07 million barrels (170,000 m3) per day. This is a substantial decline from the 1990s, due primarily to ageing oil fields and a lack of investment in oil production equipment. This decline in production has been accompanied by a substantial increase in domestic consumption, about 5.4% per year, leading to an estimated US$1.2 billion cost for importing oil in 2005.

The state owns all petroleum and mineral rights. Foreign firms participate through production-sharing and work contracts. Oil and gas contractors are required to finance all exploration, production, and development costs in their contract areas; they are entitled to recover operating, exploration, and development costs out of the oil and gas produced. Pertamina, Indonesia's state-owned oil company.

Indonesia's fuel production has declined significantly over the years, owing to ageing oil fields and lack of investment in new equipment. As a result, despite being an exporter of crude oil, Indonesia is now a net importer of oil products. It had previously subsidised fuel prices to keep prices low, costing US$7 billion in 2004 .[75] The current president has mandated a significant reduction of government subsidy of fuel prices in several stages .[76] The government has stated the cuts in subsidies are aimed at reducing the budget deficit to 1% of gross domestic product (GDP) this year, down from around 1.6% last year. At the same time, to alleviate economic hardships, the government has offered one-time subsidies to qualified citizens.

Mining

Indonesia is the world's largest tin market. Although mineral production traditionally centred on bauxite, silver, and tin, Indonesia is expanding its copper, nickel, gold, and coal output for export markets.

In mid-1993, the Department of Mines and Energy reopened the coal sector to foreign investment, with the result that the leading Indonesian coal producer now is a joint venture between UK firms – BP and Rio Tinto. Total coal production reached 74 million metric tons in 1999, including exports of 55 million tons. 2011 coal production was 353 million tons. As of 2014, Indonesia is the third largest producer with a total production of 458 Mt and export of 382 Mt.[77] At this production rate, the reserves will be used up in 61 years, i.e. around the year 2075.[78] Not all of the productions can be exported due to there are Domestic Market Obligation (DMO) regulation which should fulfill the domestic market. In 2012, the DMO is 24.72%. And starting 2014, there are no low-grade coal exports allowed, so the upgraded brown coal process which crank up the calorie value of coal from 4,500 kcal/kg to 6,100 kcal/kg will be built in South Kalimantan and South Sumatra.[79]

Two US firms operate three copper/gold mines in Indonesia, with a Canadian and British firm holding significant other investments in nickel and gold, respectively. In 1998, the value of Indonesian gold production was $1 billion and copper, $843 million. Receipts from gold, copper, and coal comprised 84% of the $3 billion. Earned in 1998 by the mineral mining sector. India fortune groups like Vedanta Resources and Tata Group have significant mining operations in Indonesia.

April 2011: With additional of Tayan, West Kalimantan Alumina project which produce 5% of the world's alumina production, Indonesia will be the world's second largest Alumina producer. The project will not make the ores to become Aluminium due to there are 100 types of Alumina derivatives which can be developed further by other companies in Indonesia.[80]

Joko Widodo's administration continued the resource nationalism policy of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, nationalizing some assets controlled by multinational companies such as Freeport McMoRan, Total SA and Chevron. In 2018, in a move aimed to cut imports, oil companies operating in Indonesia were ordered to sell their crude oil to state-owned Pertamina.[81]

Non-oil and gas manufacturing

In 2010, Indonesia sales 7.6 million motorcycles, which mainly produce in Indonesia with almost 100% local components. Honda led the market with a 50.95% market share, followed by Yamaha with 41.37% market share.[82]

In 2011, the retail car sales total was 888,335 units, a 19.26% increase from last year. Toyota dominated the domestic car market by 35.34%, followed by Daihatsu and Mitsubishi with 15.44% and 14.56%, respectively.[83] Since 2011, some origin local car makers have introduced some Indonesian national cars which can be categorised as Low Cost Green Car (LCGC). In 2012, significant increased by 24.8 percent made automobile sales broke 1 million units with 1.116 million units.[84]

Indonesian Textile Association has reported that in 2013, the textile sector is likely to attract investment of around $175 million. In 2012, the investment in this sector was $247 million, of which only $51 million was for new textile machinery.[85] Exports from the textile sector in 2012 was $13.7 billion.

Electricity, gas and water supply

Main statistics on output in 2006 are provided in the table above.

Indonesia has expressed interest recently in possible use of nuclear plants. Indonesia has run 3 research reactors.

Pertamina and Perusahaan Gas Negara are the state-owned oil company. Perusahaan Listrik Negara is the state-owned electricity company.

Transportation and communication

According to Deloitte, in 2011 Internet-related activities in Indonesia have generated 1.6% of the nation's gross domestic product (GDP). This is bigger than electronic and electrical equipment exports and liquified natural gas at 1.51% and 1.45% respectively.[86]

Finance, real estate and business services

In 2015, Indonesia financial services covered Rp 7,289 trillion, 70.5 percent held by 50 conglomerations (domestic and/or foreign ownerships) which 14 of it were vertical conglomerations, 28 were horizontal conglomerations and 8 are mixed conglomerations. 35 mainly entities are in bank industries, 1 was in capital market industries, 13 were in non-bank industries, and 1 was in special financial industries.[87]

Micro-businesses

There are 50 million small businesses in Indonesia with online usage growth of 48% in 2010, so Google will open a local office in Indonesia before 2012.[88]

Automotive

Year to date August 2014, Indonesia export 126,935 Completelety Build Up (CBU) vehicle units and 71,000 Completely Knock Down (CKD) vehicle units, while the total production is 878,000 vehicle units, so the export is 22.5 percent of total production. Automotive export is more than double of its import. Prediction, by 2020 the automotive export will be the third after CPO export and shoes export.[89]

While year to date August 2015, Indonesia export 123,790 motorcycles. The dominant manufactures, export 83,641 motorcycles and announced to make Indonesia as a base of exporting country of its products.[90]

The country produced almost 1.2 million motor vehicles in 2017, ranking it as the 18th largest producer in the world.[91] Nowadays, Indonesian automotive companies are able to produce cars with high ratio of local content (80%–90%).[92]

Public assets & services

Up to end of June 2011, the fixed state assets was Rp 1,265 trillion ($128 billion), while the value of state stocks was Rp 50 trillion ($5.0 billion) and other state assets was Rp 24 trillion ($2.4 billion). .[93]

Expatriate & migrant workers

In 2011, Indonesia released 55,010 foreigners working visas, increased by 10% compared to 2010, while the number of foreign residents in Indonesia, excluding tourists and foreign emissaries was 111,752 persons, rose by 6% to last year. Those who received visas for 6 months to one year were mostly Chinese, Japanese, South Korean, Indian, American and Australian. A few of them were entrepreneurs who made new businesses.

The most common destination of Indonesian migrant workers is Malaysia (including illegal workers). In 2010, according to a World Bank report, Indonesia was among the world's top ten remittance receiving countries with value of totalling $7 billion.[94]

In May 2011 there are 6 million Indonesian citizens working overseas, 2.2 million of whom reside in Malaysia and another 1.5 million in Saudi Arabia.[95]

Public expenditure

The total Indonesian public spending amounted to Rp 1,806 trillion (US$130.88 billion, 15.7% of GDP) in 2015. Indonesian government revenues, including revenues from state-owned enterprises, numbered Rp 1,508 trillion (US$ 109.28 billion, 13.1% of GDP) resulting in a deficit of 2.6%.[96]

Since the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s which contributed to the end of the Suharto regime in May 1998, Indonesia's public finances have undergone a major transformation. The financial crisis caused a huge economic contraction and a commensurate decline in public spending. Debt and public subsidies increased dramatically while development spending was sharply curtailed.

Now, one decade later, Indonesia has moved out of crisis and into a situation in which the country once again has sufficient financial resources to address its development needs. This change has come about as a result of prudent macroeconomic policies, the most important of which has been very low budget deficits. Also, the way in which the government spends money has been transformed by the 2001 "big bang" decentralisation, which has resulted in over one-third of all government spending being transferred to sub-national governments by 2006. Equally important, in 2005, spiraling international oil prices caused Indonesia's domestic fuel subsidies to run out of control, threatening the country's hard won macroeconomic stability. Despite the political risks of major price hikes in fuel driving more general inflation, the government took the brave decision to slash fuel subsidies.

This decision freed up an extra US$10 billion for government spending on development programs.[97] Meanwhile, by 2006 an additional US$5 billion had become available thanks to a combination of increased revenues boosted by steady growth of the overall economy, and declining debt service payments, a hangover from the economic crisis.[97] This meant that in 2006 the government had an extra US$15 billion to spend on development programs.[97] The country has not seen "fiscal space" of such magnitude since the revenue windfall experienced during the oil boom of the mid-1970s. However, an important difference is that the 1970s oil revenue windfall was just that: a lucky and unforeseen financial boon. In contrast, the current fiscal space has been achieved as a direct result of sound and carefully thought through government policy decisions.

However, while Indonesia has made significant progress in freeing up financial resources for its development needs, and this situation is set to continue in the next few years, subsidies continue to place a heavy burden on the government’s budget. The 2005 reductions on subsidies notwithstanding, total subsidies still accounted for close to US$30 billion in government spending in 2012, or over 15% of the total budget.[97]

One of the results of the Habibie government (May 1998 to August 2001) to decentralise power across the country in 2001 was that increasingly high shares of government spending have been channelled through sub-national governments. As a result, provincial and district governments in Indonesia now spend around 40% of total public funds, which represents a level of fiscal decentralisation that is even higher than the OECD average.

Given the level of decentralisation that has occurred in Indonesia and the fiscal space now available, the Indonesian government has a unique opportunity to revamp the country’s neglected public services. If carefully managed, this could allow the lagging regions of eastern Indonesian to catch up with other more affluent areas of the country in terms of social indicators. It could also enable Indonesian to focus on the next generation of reforms, namely improving quality of public services and targeted infrastructure provision. In effect, the correct allocation of public funds and the careful management of those funds once they have been allocated have become the main issues for public spending in Indonesia going forward.

For example, while education spending has now reached 17.2% of total public spending ─ the highest share of any sector and a share of 3.9% of GDP in 2006, compared with only 2.0% of GDP in 2001 ─ in contrast total public health spending remains below 1.0% of GDP.[97] Meanwhile, public infrastructure investment has still not fully recovered from its post-crisis lows and remains at only 3.4% of GDP.[97] One other area of concern is that the current level of expenditure on administration is excessively high. Standing at 15% in 2006, this suggests a significant waste of public resources.[97][98]

Economic challenges

It was only until changes in government in 1965 that triggered off essential progress in lowering the country's poverty rate. From a steep recession in 1965 with an 8% decline in GDP, the country began to develop economically in the 1970s, earning much benefit from the oil shock. This development continued throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s despite the oil counter-shocks. During these periods, GDP level rose at an average rate of 7.1%. Indonesia saw consistent growth, with the official poverty rate falling from 60% to 15%.[99] Despite this development, an estimated 13.33% of the population (2010 estimate) remains below the poverty line.[100]

Labor unrest

As of 2011 labour militancy was increasing in Indonesia with a major strike at the Grasberg mine and numerous strikes elsewhere. A common issue was attempts by foreign-owned enterprises to evade Indonesia's strict labour laws by calling their employees contract workers. The New York Times expressed concern that Indonesia's cheap labour advantage might be lost. However, a large pool of unemployed who will accept substandard wages and conditions remains available. One factor in the increase of militancy is increased awareness via the internet of prevailing wages in other countries and the generous profits foreign companies are making in Indonesia.[101]

On 1 September 2015, thousands of workers in Indonesia staged demonstrations across the country in pursuit of higher wages and improved labour laws. Approximately 35,000 people rallied in several parts of the country. They demanding 22 to 25 per cent increase in minimum wage by 2016 and lower prices on essential goods, including fuel. The unions also want government to ensure job security and provide the basic rights of the workers.[102]

Inequality in development

Economic disparity and the flow of natural resource profits to Jakarta has led to discontent and even contributed to separatist movements in areas such as Aceh and Irian Jaya. Geographically, the poorest fifth regions account for just 8% of consumption, while the richest fifth account for 45%. While there are new laws on decentralisation that may address the problem of uneven growth and satisfaction partially, there are many hindrances in putting this new policy into practice.[99]

At the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (Kadin) meeting at Makassar on April 2011, Disadvantaged Regions Minister said there are 184 regencies classified as disadvantaged areas in Indonesia with around 120 regencies were located in the eastern part of Indonesia.[103]

Unequal distribution of wealth

Indonesia can be categorized as an unequal country due to in June 2016, one percent of its population have 49.3 percent of the Indonesia's $1.8 trillion wealth. The number is better than last year number with 53.5 percent, however it is the fourth rank after Russia with 74.5 percent, India 58.4 percent and Thailand 58 percent.[104]

Inflation

Inflation has long been another problem in Indonesia. Because of political turmoil, the country had once suffered hyperinflation, with 1,000% annual inflation between 1964 and 1967,[105] and this had been enough to create severe poverty and hunger.[106] Even though the economy recovered very quickly during the first decade of New Order administration (1970–1981), never once was the inflation less than 10% annually. The inflation slowed during the mid-1980s, however, the economy was also languid due to the decrease of oil price that reduced its export revenue dramatically. The economy was again experiencing rapid growth between 1989–1997 due to the improving export-oriented manufacturing sector, still the inflation rate was higher than economic growth, and this caused widening gap among several Indonesians. The inflation peaked in 1998 during the Asian financial crisis, with over 58%, causing the raise in poverty level as bad as the 1960s crisis.[107] During the economic recovery and growth in recent years, the government has been trying to decline the inflation rate. However, it seems that Indonesian inflation has been affected by the global fluctuation and domestic market competition.[108] As of 2010, the inflation rate was approximately 7%, when its economic growth was 6%. To date, inflation is affecting Indonesian lower middle class, especially those who can't afford food after price hikes.[109][110]

Regional economic performance

Based on the regional administration implementation performance evaluation of 2009, by an order the best performance were:

- 3 Provinces: North Sulawesi, South Sulawesi and Central Java;

- 10 Regencies: Jombang and Bojonegoro in East Java Province, Sragen and Pacitan in Central Java, Boalemo in Gorontalo, Enrekang in South Sulawesi, Buleleng in Bali, Luwu Utara in South Sulawesi, Karanganyar in Central Java and Kulon Progo in Yogyakarta;

- 10 Cities: Surakarta and Semarang in Central Java, Banjar in West Java, Yogyakarta city in Yogyakarta, Cimahi in West Java, Sawahlunto in West Sumatra, Probolinggo and Mojokerto in East java, Sukabumi and Bogor in West Java.[111]

Based on JBIC Fiscal Year 2010 survey (22nd Annual Survey Report) found that in 2009, Indonesia has the highest satisfaction level in net sales and profits for the Japanese companies.[112]

High-net-worth individuals

According to Asia Wealth Report, Indonesia has the highest growth rate of high-net-worth individuals (HNWI) predicted among the 10 most Asian economies.[113]

The Wealth Report 2015 by Knight Frank reported that in 2014 there were 24 individuals with a net worth above US$ 1 billion. 18 of them lived in Jakarta and the others spread among other large cities in Indonesia. 192 persons can be categorised as centamillionaires with over US$ 100 million of wealth and 650 persons as high-net-worth individuals with wealth exceeding US$ 30 million.[114]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects – Indonesia". International Monetary Fund. April 2018.

- ↑ "World Bank forecast for Indonesia, June 2018 (p. 151)" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ↑ "The World Bank In Indonesia". World Bank. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ↑ "Strategies to Combat Indonesia's Income Distribution Inequality". Indonesia Investment. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2018" (PDF). United Nations Development Program. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ↑ "Vice President: Indonesia will move on". Investvine.com. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ↑ "Ease of Doing Business in Indonesia". World Bank. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ↑ "Federation of International Trade Associations : Indonesia profile". Fita.org. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Trade Profile of Indonesia". World Trade Organization. 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ↑ "Trade Profile of Indonesia". World Trade Organization. 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ↑ "COUNTRY COMPARISON :: STOCK OF DIRECT FOREIGN INVESTMENT – AT HOME". The World Factbook. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ↑ "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Moody's changes outlook on Indonesia's rating to positive from stable, affirms government bond rating at Baa3". Global Credit Research. February 8, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Fitch Affirms Indonesia at 'BBB'; Outlook Stable".

- ↑ "RI's forex reserves up $0.13 bln in October". Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ↑ What is the G-20 Archived 4 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine., g20.org. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ↑ "Kemenperin – Ketika Swasta Mendominasi". Archived from the original on 2017-08-05.

- ↑ "80 Persen Industri Indonesia Disebut Dikuasai Swasta". 3 March 2015.

- ↑ "Kemenperin – Pengelola Kawasan Industri Didominasi Swasta". Archived from the original on 2017-08-05.

- ↑ "Acicis – Dspp". Acicis.murdoch.edu.au. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ data.worldbank.org http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2016&locations=ID&start=2006. Retrieved 2017-08-05. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Lindblad, J. Thomas (2006). "Macroeconomic consequences of decolonization in Indonesia" (PDF). XIVth conference of the International Economic History Association. Helsinki. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ↑ "History – BNI". BNI. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ↑ Hakiem, Lukman (9 August 2017). "Hatta-Sjafruddin: Kisah Perang Uang di Awal Kemerdekaan" (in Indonesian). Republika. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ↑ "Period of Recognition of the Republic of Indonesia's Sovereignty up the Nationalization of DJB" (PDF). Bank Indonesia. Special Unit for Bank Indonesia Museum: History Before Bank Indonesia. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ↑ Lindblad, J. Thomas (2004). "From Java Bank to Bank Indonesia: A Case Study of Indonesianisasi in Practice" (PDF). Archived from the original on 27 March 2009.

- ↑ van de Kerkhog\f, Jasper (March 2005). "Dutch enterprise in independent Indonesia: cooperation and confrontation, 1949–1958" (PDF). IIAS Newsletter. 36. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ↑ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 292. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ↑ Schwarz (1994), pp. 52–7.

- ↑ (Schwarz (1994), pages 52–57)

- ↑ Schwarz (1994), pages 52–57.

- ↑ "Indonesia: Country Brief". Indonesia: Key Development Data & Statistics. The World Bank. September 2006.

- ↑ "GDP info". Earthtrends.wri.org. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Combating Corruption in Indonesia, World Bank 2003" (PDF). Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Transparency International Global Corruption Report 2004". Transparency.org. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Suharto tops corruption rankings". BBC News. 25 March 2004. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ Robison, Richard (17 November 2009). "A Slow Metamorphosis to Liberal Markets". Australian Financial Review.

- ↑ "Historical Exchange Rates". OANDA. 16 April 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ http://www.xe.com/currencycharts/?from=USD&to=IDR&view=10Y

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ↑ van der Eng, Pierre (4 February 2002). "Indonesia's growth experience in the 20th century: Evidence, queries, guesses" (PDF). Australian National University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ↑ Temple, Jonathan (15 August 2001). "Growing into trouble: Indonesia after 1966" (PDF). University of Bristol. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ↑ BBC News (31 August 2005). "Indonesia plans to slash fuel aid". BBC, London.

- ↑ The Jakarta Post. 2007 https://web.archive.org/web/20071214184114/http://www.thejakartapost.com/detailgeneral.asp?fileid=20071105212913&irec=37. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2007. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Beberapa Indikator Penting Mengenai Indonesia" (PDF) (Press release) (in Indonesian). Indonesian Central Statistics Bureau. 2 December 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ↑ "Indonesia: Economic and Social update" (PDF) (Press release). World Bank. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved April 2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Indonesia: BPS-STATISTICS INDONESIA STRATEGIC DATA" (PDF) (Press release). BPS-Statistic Indonesia. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2010. Retrieved November 2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "IMF Survey: Indonesia's Choice of Policy Mix Critical to Ongoing Growth". Imf.org. 28 July 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Indonesian President Joko 'Jokowi' Widodo Two Years On". Time. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ↑ "Jokowi Heads to 2018 With Backing of Stronger Indonesian Economy". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ↑ "Indonesian GDP Growth Disappoints, Adding to Currency Woes". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ↑ "Indonesian GDP growth falls short in 1Q, pressuring President Widodo". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ↑ Post, The Jakarta. "Number of unemployed rises to 7.04 million". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 2018-01-28.

- ↑ Bloomberg Terminal

- ↑ "Economy risks losing momentum: Experts". The Jakarta Post. 26 November 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Doing Business Survey, World Bank". Doingbusiness.org. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Statistics on Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A)". Imaa-institute.org. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Indonesia aims to boost FDI by 23%". Investvine.com. 24 January 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ↑ A copy of the Masterplan is available at the website of the Indonesian Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs.

- ↑ "Moody's Also Says Indonesia Economy Now Investment Grade". 18 January 2012. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ "Indonesia Raised to Investment Grade by S&P on Budget Curbs". Bloomberg.com. 2017-05-19. Retrieved 2018-01-28.

- ↑ "Indonesia". Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Indonesia forges stronger ties with China to boost economy". November 19, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ↑ Investments, Indonesia. "Indonesia-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (IJEPA) Reviewed | Indonesia Investments". www.indonesia-investments.com. Retrieved 2018-01-28.

- ↑ "Edit/Review Countries". Imf.org. 14 September 2006. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Indonesia: average net wage by sector 2017 | Statistic". Statista. Retrieved 2018-01-28.

- ↑ "Indonesia's Dec annual inflation rate at 3.61 pct, above forecast". NASDAQ.com. 2018-01-01. Retrieved 2018-01-28.

- ↑ Estu Suryowati (12 August 2014). "Satu Dekade, Kontribusi Pertanian terhadap PDB Menurun". Kompas (in Indonesian).

- 1 2 "Pertanian di Indonesia (Agriculture in Indonesia)". Indonesia Investments. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ McClanahan, Paige (11 September 2013). "Can Indonesia increase palm oil output without destroying its forest?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ↑ "Palm Oil". Greenpeace. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "Indonesia to replant 4.7m hectares of palm oil plantation". UkrAgroConsult. 30 August 2017. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ↑ Sarif, Edy (17 June 2011). "Malaysia expected to maintain position as world's largest producer of Certified Sustainable Palm Oil". The Star Online. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ↑ "Tigers count the cost of easing fuel subsidies". Asia Times. 10 March 2005. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Indonesia plans to slash fuel aid". BBC News. 31 August 2005.

- ↑ http://www.indonesia-investments.com/business/commodities/coal/item236

- ↑ https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/pdf/energy-economics/statistical-review-2015/bp-statistical-review-of-world-energy-2015-full-report.pdf

- ↑ "Coal production may reach 370 million tons this year". 23 September 2011.

- ↑ "RI aims to be second largest alumina producer". Antara News. 12 April 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Economic nationalism is back in Indonesia as election approaches". The Straits Times. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ "Honda eyes larger share in premium bike market". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Local automobile sales hit all-time high". 5 January 2012.

- ↑ "Penjualan mobil capai 1,1 juta unit di 2012". 8 January 2013.

- ↑ "Indonesia textile sector faces challenge". Investvine.com. 2 February 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ↑ "Internet penetration and the connected archipelago". 31 December 2011.

- ↑ "Siaran Pers: OJK Awasi 50 Konglomerasi Keuangan". 26 June 2015. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ↑ "Google to Open Indonesia Office 'Before 2012'". Embassyofindonesia.org. 22 July 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Optimisme Ekspor Mobil Terus Menanjak". Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ "Roda dua makin ngacir ke luar negeri". 14 September 2015.

- ↑ "2017 Production Statistics". Organisation Internationale des Constructeurs d'Automobiles. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ↑ "Localization". PT. Toyota Motor Manufacturing Indonesia. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ↑ "Indonesia's State Assets Worth IDR1,338.7 Trillion". 2 January 2011. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ "Indonesia Among the World's Top 10 Remittance Receivers". Embassyofindonesia.org. 4 May 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "After Malaysia, RI seeks similar pact with S. Arabia". The Jakarta Post. 19 August 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Indonesia Economic Quarterly – January 2017" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Spending for Development: Making the Most of Indonesia's New Opportunities Indonesia Public Expenditure Review 2007" (PDF). Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "The Politics of Free Public Services in Decentralised Indonesia" (PDF). Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Indonesia Poverty and wealth, Information about Poverty and wealth in Indonesia". Nationsencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. 20 October 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ Sara Schonhardt (26 December 2011). "As Indonesia Grows, Discontent Sets in Among Workers". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ Kaniz Fatima (9 September 2015). "Textile workers protest for new minimum wage in Indonesia". BanglaApparel.com.

- ↑ "120 poor regencies are in the east". The Jakarta Post. 18 July 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Indonesia's Richest One Percent Controls Nearly Half of Nation's Wealth: Report". Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ↑ By the time of Sukarno's downfall in the mid-1960s, the economy was in chaos with 1,000% annual inflation, shrinking export revenues, crumbling infrastructure, factories operating at minimal capacity, and negligible investment. Schwarz (1994), pages 52–57

- ↑ "Ir Soekarno The First President of Indonesia". Welcome2indonesia.com. 18 May 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Imf.org. 14 September 2006. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Indonesia – Financial & Private Sector Development in Indonesia". World Bank. 18 October 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Faced With Skyrocketing Food Prices, Indonesian Govt to Speed Up Work on Food Estate". Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Indonesia Inflation Accelerates, Adding Pressure to Raise Rate :: Forex Trading Lebanon". Forextradinglb.com. 1 February 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Govt names 23 regions with best performance". Waspada.co.id. 25 April 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "The power nature and Indonesia's economy". The Jakarta Post. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ "Close to 100,000 Super Rich Indonesians By 2015: Report". 2 September 2011. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- ↑ Hilda B Alexander (19 March 2015). "18 Konglomerat Indonesia Tinggal di Jakarta".

Further reading

- Eng, Pierre van der (2010). "The sources of long-term economic growth in Indonesia, 1880–2008". Explorations in Economic History. 47 (3): 294–309. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2009.08.004.

External links

- Indonesia Economic Aftershock from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- BKPM – Indonesia Investment Coordinating Board And Indonesia Investment News

- Comprehensive current and historical economic data

- World Bank Summary Trade Statistics Indonesia

- Tariffs applied by Indonesia as provided by ITC's Market Access Map, an online database of customs tariffs and market requirements