Garuda

| Garuda | |

|---|---|

Garuda at the National Museum in New Delhi. |

The Garuda is a legendary bird or bird-like creature in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain mythology.[1][2][3] He is variously the vehicle mount (vahana) of the Hindu god Vishnu, a dharma-protector and Astasena in Buddhism, and the Yaksha of the Jain Tirthankara Shantinatha.[2][3][4]

Garuda is described as the king of birds and a kite-like figure.[5][6] He is shown either in zoomorphic form (giant bird with partially open wings) or an anthropomorphic form (man with wings and some bird features). Garuda is generally a protector with power to swiftly go anywhere, ever watchful and an enemy of the serpent.[1][6][7] He is also known as Tarkshya and Vynateya.[8]

Garuda is a part of state insignia in India, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia and Indonesia. The Indonesian official coat of arms is centered on the Garuda. The national emblem of Indonesia is called Garuda Pancasila.[9]

Hinduism

In Hinduism, Garuda is a divine eagle-like sun bird and the king of birds.[5] A Garutman is mentioned in the Rigveda who is described as celestial deva with wings.[10][11] The Shatapatha Brahmana embedded inside the Yajurveda text mentions Garuda as the personification of courage. In the Mahabharata, Garutman is stated to be same as Garuda, then described as the one who is fast, who can shapeshift into any form and enter anywhere.[10] He is a powerful creature in the epics, whose wing flapping can stop the spinning of heaven, earth and hell. He is described to be the vehicle mount of the Hindu god Vishnu, and typically they are shown together.[10]

According to George Williams, Garuda has roots in the verb gri, or speak.[11] He is a metaphor in the Vedic literature for Rik (rhythms), Saman (sounds), Yajna (sacrifices), and the atman (Self, deepest level of consciousness). In the Puranas, states Williams, Garuda becomes a literal embodiment of the idea, and the Self who attached to and inseparable from the Supreme Self (Vishnu).[11][12] Though Garuda is an essential part of the Vaishnavism mythology, he also features prominently in Shaivism mythology, Shaiva texts such as the Garuda Tantra and Kirana Tantra, and Shiva temples as a bird and as a metaphor of atman.[12][13][14]

Iconography

The Hindu texts on Garuda iconography vary in their details. If in the bird form, he is eagle-like, typically with the wings slightly open as if ready and willing to fly wherever he needs to.[6] In part human-form, he may have an eagle-like nose, beak or legs, his eyes are open and big, his body is the color of emerald, his wings are golden-yellow. He may be shown with either two or four hands.[6] If he is not carrying Vishnu, he holds a jar of amrita (immortality nectar) in one hand in the rear and an umbrella in the other, while the front pair of hands are in anjali (namaste) posture. If he is carrying Vishnu, the rear hands provide the support for Vishnu's feet.[6][7]

According to the text Silparatna, states Rao, Garuda is best depicted with only two hands and with four bands of colors: "golden yellow color from feet to knees, white from knees to navel, scarlet from navel to neck, and black above the neck". His hands, recommends the text, should be in abhaya (nothing to fear) posture.[6] In Sritatvanidhi text, the recommended iconography for Garuda is a kneeling figure, who wears one or more serpents, pointed bird-beak like nose, his two hands in namaste posture. This style is commonly found in Hindu temples dedicated to Vishnu.[6]

In some iconography, Garuda carries Lord Vishnu and his two consorts by his side: Lakshmi(Thirumagal) and Bhūmi (Bhuma-Devi).[8][16]

Garuda iconography is found in early temples of India, such as on the underside of the eave at Cave 3 entrance of the Badami cave temples (6th-century).[6][17]

Mythology

_in_the_background.jpg)

Garuda mythology is linked to that of Aruna – the charioteer of Surya (Sun god). However, these Indian mythologies are different, inconsistent across the texts. Both, Aruna and Garuda, developed from egg. According to one version, states George Williams, Kashyapa Prajapati's two wives Vinata and Kadru wanted to have children. Kashyapa granted them a boon.[18] Kadru asked for one thousand Nāga sons, while Vinata wanted two, each equal to Kadru's thousand naga sons. Kashyapa blessed them, and then went away to a forest to meditate. Later, Kadru gave birth to one thousand eggs, while Vinata gave birth to two eggs. These incubated for five hundred years, upon which Kadru's eggs broke open and out came her 1,000 sons. Vinata eager for her sons, impatiently broke one of the eggs from which emerged the partially formed Aruna, who looked radiant and reddish as the morning sun but not as bright as the midday sun.[18][19] Aruna chided his mother, Vinata for her impatience since he was born without legs and warned her to not break open the second egg but wait. Aruna then left to become the charioteer of Surya, the sun god.

Vinata waited, and after many years the second egg hatched, and Garuda was born. Garuda later went to war with his step brothers, the Nagas.[18][20]

Some myths present Garuda as so massive that he can block out the sun.[21] The text Garuda Purana is named after him.[22]

Garuda is presented in the Mahabharata mythology as one who eats snake meat, such as the story about he planning to kill and eat Sumukha snake, where Indra attempts to intervene.[23] Garudas are also a race of birds who devour snakes in the epic.[23]

Symbolism

Garuda's links to Vishnu – the Hindu god who fights injustice and destroys evil in his various avatars to preserve dharma, has made him an iconic symbol of king's duty and power, an insignia of royalty or dharma. His eagle-like form is shown either alone or with Vishnu, signifying divine approval of the power of the state.[11] He is found on the faces of many early Hindu kingdom coins with this symbolism, either as a single headed bird or a three-headed bird that watches all sides.[24]

Throughout the Mahabharata, Garuda is invoked as a symbol of impetuous violent force, of speed, and of martial prowess. Powerful warriors advancing rapidly on doomed foes are likened to Garuda swooping down on a serpent. Defeated warriors are like snakes beaten down by Garuda. The Mahabharata character Drona uses a military formation named after Garuda. Krishna even carries the image of Garuda on his banner.

Buddhism

Garuda, also referred to as Garula (Pali Cheeki Breeki), are golden-winged birds in Buddhist texts. Under the Buddhist concept of saṃsāra, they are one of the Aṣṭagatyaḥ, the eight classes of inhuman beings. In Buddhist arts, they are shown as sitting and listening to the sermons of the Buddha.[1] They are enemies of Nagas (snakes) and therefore sometimes depicted with a serpent held between their claws. Like the Hindu arts, both zoomorphic (giant eagle-like bird) and partially anthropomorphic (part bird, part human) iconography has been common in Buddhism.[1]

In Buddhism, the Garuda (Pāli: garuḷā) are enormous predatory birds with wings span of 330 yojanas.[1] They are described as beings with intelligence and social organization. Another name for the Garuda is suparṇa (Pāli: supaṇṇa), meaning "well-winged, having good wings". Like the Naga, they combine the characteristics of animals and divine beings, and may be considered to be among the lowest devas.[1] The Garudas have kings and cities, and at least some of them have the magical power of changing into human form when they wish to have dealings with people. On some occasions Garuda kings have had romances with human women in this form. Their dwellings are in groves of the simbalī, or silk-cotton tree.

Jataka stories describe them to be residents of Nagadipa or Seruma.[1]

The Garuda are enemies to the nāga, a race of intelligent serpent- or dragon-like beings, whom they hunt. The Garudas at one time caught the nāgas by seizing them by their heads; but the nāgas learned that by swallowing large stones, they could make themselves too heavy to be carried by the Garudas, wearing them out and killing them from exhaustion. This secret was divulged to one of the Garudas by the ascetic Karambiya, who taught him how to seize a nāga by the tail and force him to vomit up his stone (Pandara Jātaka, J.518).

The Garudas were among the beings appointed by Śakra to guard Mount Sumeru and the Trāyastriṃśa heaven from the attacks of the asuras.

In the Maha-samaya Sutta (Digha Nikaya 20), the Buddha is shown making temporary peace between the Nagas and the Garudas.

In the Qing Dynasty fiction The Story of Yue Fei (1684), Garuda sits at the head of the Buddha's throne. But when a celestial bat (an embodiment of the Aquarius constellation) flatulates during the Buddha’s expounding of the Lotus Sutra, Garuda kills her and is exiled from paradise. He is later reborn as Song Dynasty General Yue Fei. The bat is reborn as Lady Wang, wife of the traitor Prime Minister Qin Hui, and is instrumental in formulating the "Eastern Window" plot that leads to Yue's eventual political execution.[25] The Story of Yue Fei plays on the legendary animosity between Garuda and the Nagas when the celestial bird-born Yue Fei defeats a magic serpent who transforms into the unearthly spear he uses throughout his military career.[26] Literary critic C. T. Hsia explains the reason why Qian Cai, the book's author, linked Yue with Garuda is because of the homology in their Chinese names. Yue Fei's courtesy name is Pengju (鵬舉).[27] A Peng (鵬) is a giant mythological bird likened to the Middle Eastern Roc.[28] Garuda's Chinese name is Great Peng, the Golden-Winged Illumination King (大鵬金翅明王).[27]

Jainism

The garuda is a yaksha or guardian for Shantinatha in Jain iconography and mythology.[2][3] Jain iconography shows Garuda as a human figure with wings and a strand-circle.[29]

As a cultural and national symbol

In India, Indonesia and the rest of Southeast Asia the eagle symbolism is represented by Garuda, a large bird with eagle-like features that appears in both Hindu and Buddhist epic as the vahana (vehicle) of the god Vishnu. Garuda became the national emblem of Thailand and Indonesia; Thailand's Garuda is rendered in a more traditional anthropomorphic style, while that of Indonesia is rendered in heraldic style with traits similar to the real Javan hawk-eagle.

India

India primarily uses Garuda as a martial motif:

- Garud Commando Force is a Special Forces unit of the Indian Air Force, specializing in operations deep behind enemy lines.[30]

- Brigade of the Guards of the Indian Army uses Garuda as their symbol

- Elite bodyguards of the medieval Hoysala kings were called Garudas

- Kerala and Andhra pradesh state road transport corporations use Garuda as the name for a/c moffusil buses

- Garuda rock, a rocky cliff in Tirumala in Andhra pradesh

- The insignia of the 13th century Aragalur chief, Magadesan, included Rishabha the sacred bull and the Garuda

Cambodia

The word Garuda (Khmer: គ្រុឌ - " Krud ") is literally derived from Sanskrit.

- In Cambodia, Khmer architects have used the Garuda sculptures as the exquisite ornate to equip on temples, viharas of wat and many elite houses since ancient time, especially from Khmer empire era until nowadays.

- Garuda is also mentioned in many legendary tales as the vehicle of Vishnu and its main rival is Naga.[31]

Indonesia

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Garuda in Indonesia. |

Indonesia uses the Garuda, called the Garuda Pancasila, as its national symbol. It is somewhat intertwined with the concept of the phoenix.

- Garuda Pancasila is coloured or gilt gold, symbolizes the greatness of the nation and is a representation of the elang Jawa or Javan hawk-eagle Nisaetus bartelsi. The black color represents nature. There are 17 feathers on each wing, 8 on the lower tail, 19 on the upper tail and 45 on the neck, which represent the date Indonesia proclaimed its independence: 17 August 1945. The shield it carries with the Indonesian Panca Sila heraldry symbolizes self-defense and protection in struggle.[9]

- Indonesian national airline is Garuda Indonesia.

- Indonesian Armed Forces United Nations peacekeeping missions is known as Pasukan Garuda or Garuda Contingent

- Airlangga University, one of the oldest and leading university in Indonesia uses Garuda on its emblem. The emblem, containing a Garuda in a blue and yellow circle, is called "Garudamukha", and depicts Garuda as the bearer of knowledge, carrying a jug of Amrita, the water of eternity, symbolizing eternal knowledge.

- In Bali and Java Garuda has become a cultural symbol, the wooden statue and mask of Garuda is a popular artworks and souvenirs.

- In Bali, we can find the tallest Garuda statue of 18 metres tall made from tons of copper and brass. The statue is located in Garuda Wisnu Kencana complex.

- Garuda has identified as Indonesian national football team in international games, namely "The Garuda Team".[32]

- The stylized brush stroke that resemble Garuda appears in the logo of 2011 Southeast Asian Games, held in Palembang and Jakarta, Indonesia.

- The stylized curves that took form of Garuda Pancasila appears in the logo of Wonderful Indonesia tourism campaign.

- Garuda becomes the inspiration for national costumes worn by Puteri Indonesia at Miss Universe 2012 and Miss Universe 2016 beauty pageant.

Japan

- The Karura (迦楼羅?) is a divine creature with human torso and birdlike head in Japanese Hindu-Buddhist epics.[33]

- The name is a transliteration of Garuda (Sanskrit: Garuḍa गरुड ; Pāli: Garuḷa) a race of enormously gigantic birds in Hinduism, upon which the Japanese Buddhist version is based. The same creature may go by the name of konjichō (金翅鳥?, lit. "gold-winged bird", Skr. suparṇa).

Mongolia

- The Garuda, known as Khangarid, is the symbol of the capital city of Mongolia, Ulan Bator.[34] According to popular Mongolian belief, Khangarid is the mountain spirit of the Bogd Khan Uul range who became a follower of Buddhist faith. Today he is considered the guardian of that mountain range and a symbol of courage and honesty.

- Khangarid (Хангарьд), a football (soccer) team in the Mongolia Premier League also named after Garuda.

- Garuda Ord (Гаруда Орд), a private construction and trading company based in Ulaanbaatar, also named after Garuda.

- State Garuda (Улсын Гарьд) is a title given to the debut runner up in wrestling tournament during Mongolian National Festival Naadam.

Myanmar

Nepal

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Garuda in Nepal. |

Garuda is found in Nepalese traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism.

Suriname

- In Suriname, there is a radio and TV station called Radio en Televisie Garuda, which broadcasts programming from Indonesia, particularly Java, aimed at the Javanese Surinamese population.

Thailand

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Garuda in Thailand. |

Thailand uses the Garuda (Thai: ครุฑ, khrut) as its national symbol,[36] as well as their currency.[37]

- One form of the Garuda used in Thailand as a sign of the royal family is called Khrut Pha, meaning "Garuda, the vehicle (of Vishnu)."

- Kingdom of Siam has an image of Garuda in their coins at least since Ayutthaya era.[37]

- The statue and images of Garuda adorn many Buddhist temples in Thailand. It also has become the cultural symbol of Thailand.

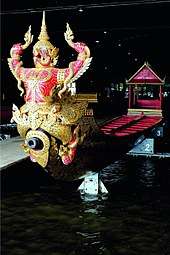

- The figure of Garuda also installed as the figurehead or masthead of Thai royal barges.

Gallery

- Insignia

Garuda as national symbol of Indonesia

Garuda as national symbol of Indonesia Garuda as national symbol of Thailand

Garuda as national symbol of Thailand Garuda (Khangardi) as the symbol of Ulan Bator, Mongolia

Garuda (Khangardi) as the symbol of Ulan Bator, Mongolia

- Coins

- Garuda iconography at a Radha Krishna Temple in Kolkata.

5th-century Gupta-era coin, Garuda with snakes in his claws

5th-century Gupta-era coin, Garuda with snakes in his claws 6th century coin with Garuda and Vishnu's chakra and conch on side

6th century coin with Garuda and Vishnu's chakra and conch on side

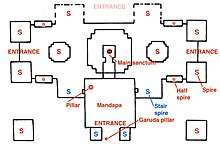

- Temples

8th century Garuda carrying Vishnu in Aihole, Karnataka, India

8th century Garuda carrying Vishnu in Aihole, Karnataka, India 8th century Garuda pillar location at a Shiva temple, Masrur Temples, Himachal Pradesh India

8th century Garuda pillar location at a Shiva temple, Masrur Temples, Himachal Pradesh India

The statues of Krut battling naga serpent, a Thai Buddhist adaptation of Garuda in Wat Phra Kaeo temple, Thailand.

The statues of Krut battling naga serpent, a Thai Buddhist adaptation of Garuda in Wat Phra Kaeo temple, Thailand. Garuda figure, gilt bronze, Khmer Empire Cambodia, 12th-13th century, John Young Museum, University of Hawaii at Manoa

Garuda figure, gilt bronze, Khmer Empire Cambodia, 12th-13th century, John Young Museum, University of Hawaii at Manoa

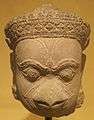

Head of a Garuda during the 14th century Cambodia, Honolulu Museum of Art

Head of a Garuda during the 14th century Cambodia, Honolulu Museum of Art Garuda returning with the vase of Amrita

Garuda returning with the vase of Amrita- Garuda at Srivilliputur Temple, Tamil Nadu, India

- Garuda pillar, Nepal

- Garuda at Durbar square in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Garuda at the funeral of King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand in 2017

Garuda at the funeral of King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand in 2017

In other media

A Garuda voiced by Robin Williams appears in the film Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb.[38]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. pp. 314–315. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- 1 2 3 Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- 1 2 3 Helmuth von Glasenapp (1999). Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 532. ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2.

- ↑ Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. pp. 249–250. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- 1 2 George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 21, 24, 63, 138. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2. , Quote: "His vehicle was Garuda, the sun bird" (p. 21); "(...) Garuda, the great sun eagle, (...)" (p. 74)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 285–287. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2.

- 1 2 3 Thomas E. Donaldson (2001). The iconography of Vaiṣṇava images in Orissa. DK Printworld. pp. 253–259.

- 1 2 Roshen Dalal (2010). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin Books. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6.

- 1 2 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 August 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- 1 2 3 4 George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- 1 2 Mark S. G. Dyczkowski (1988). The Canon of the Saivagama and the Kubjika: Tantras of the Western Kaula Tradition. State University of New York Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-88706-494-4.

- ↑ Peter Heehs (2002). Indian Religions: A Historical Reader of Spiritual Expression and Experience. New York University Press. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-0-8147-3650-0.

- ↑ Dominic Goodall (2001). Hindu Scriptures. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 341–358. ISBN 978-81-208-1770-8.

- ↑ Gupta, The Roots of Indian Art, 1980, p.29

- ↑ Bhūmi

- ↑ George Michell (2015). Badami, Aihole, Pattadakal. Jaico Publishing. pp. 49–52. ISBN 978-81-8495-600-9.

- 1 2 3 George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- ↑ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam, ed. India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 70.

- ↑ Ashok, Banker K (2012). Forest of Stories. Westland. pp. 173–175. ISBN 978-93-81626-37-5. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ Brenda Rosen (2010). Mythical Creatures Bible. Godsfield Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-1402765360.

- ↑ Ludo Rocher (1986). The Purāṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 175–177. ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5.

- 1 2 Johannes Adrianus Bernardus Buitenen (1973). The Mahabharata, Volume 3 (Book 4: The Book of the Virata; Book 5: The Book of the Effort). University of Chicago Press. pp. 167–168, 389–393. ISBN 978-0-226-84665-1.

- ↑ K. D. Bajpai (October 2004). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. pp. 19–24, 84–85, 120–124. ISBN 978-81-7017-035-8.

- ↑ Hsia, C.T. C. T. Hsia on Chinese Literature. Columbia University Press, 2004 ( ISBN 0231129904), 154

- ↑ Hsia, C. T. Hsia on Chinese Literature, pp. 149

- 1 2 Hsia, C.T. C. T. Hsia on Chinese Literature, pp. 149 and 488, n. 30

- ↑ Chau, Ju-Kua, Friedrich Hirth, and W.W. Rockhill. Chau Ju-Kua: His Work on the Chinese and Arab Trade in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, entitled Chu-Fan-Chi. St. Petersburg: Printing Office of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, 1911, p. 149, n. 1

- ↑ studies in south asian culture, Universiteit van Amsterdam. Institute of South Asian archaeology, p. 24

- ↑ Abhishek Saksena (4 January 2016). "Here's everything you need to know about Indian Air Force's elite Garud Commandos #Pathankotattacks". India Times.

- ↑ Khmer dictionary of Buddhist institute of Cambodia

- ↑ Garuda Team, http://www.google.co.nz/search?q=tim+garuda&hl=en&prmd=ivnsfd&source=lnms&tbm=isch&ei=_T2WTaaVBY_EsAO6-om7BQ&sa=X&oi=mode_link&ct=mode&cd=2&sqi=2&ved=0CBYQ_AUoAQ&biw=1920&bih=878

- ↑ "Karura 迦楼羅, Karura-Ō 迦楼羅王 (Skt. = Garuda) Bird of Life, Celestial Eagle, Half Bird Half Man". Japanese Buddhist Statuary.

- ↑ Michael Kohn. Mongolia. Lonely Planet, 2005. p. 52.

- ↑ Maitrii Aung-Thwin (2011). The Return of the Galon King: History, Law, and Rebellion in Colonial Burma. NUS Press. p. 122. ISBN 9789971695095.

- ↑ "Thailand Information". Royal Embassy of Thailand in Doha, Qatar.

- 1 2 "Garuda: a symbol on Thai currency". emuseum.treasury.go.th.

- ↑ curl=https://www.britishmuseum.org/visiting/family_visits/night_at_the_museum/fact_vs_fiction.aspx

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Garuda. |