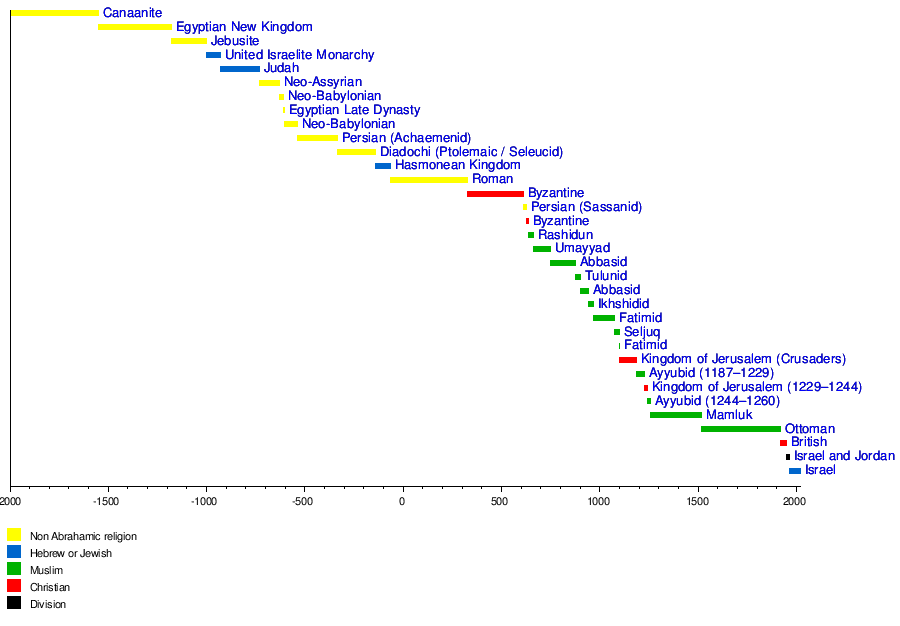

Timeline of Jerusalem

This is a timeline of major events in the History of Jerusalem; a city that had been fought over sixteen times in its history.[1] During its long history, Jerusalem has been destroyed twice, besieged 23 times, attacked 52 times, and captured and recaptured 44 times.[2]

Ancient period

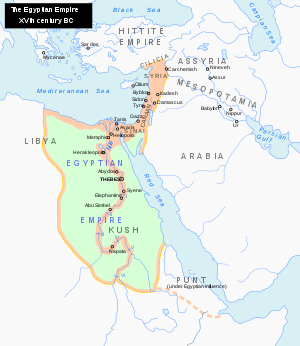

New Kingdom at its maximum territorial extent in the 15th century BCE

The Levant showing Jerusalem in c. 830 BCE

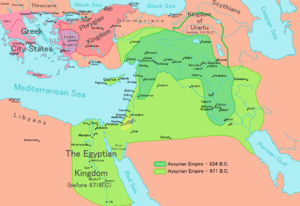

Neo-Assyrian Empire at its greatest extent

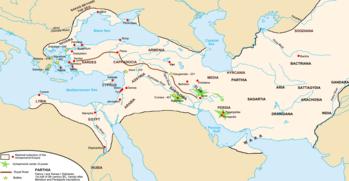

Achaemenid Empire under Darius III

Proto-Canaanite period

- 4500–3500 BCE: First settlement established near Gihon Spring (earliest archeological evidence).

- c. 2000 BCE: First known mention of the city, using the name Rusalimum, in the Middle Kingdom Egyptian Execration Texts although the identity of Rusalimum as Jerusalem has been challenged.[3][4][5] The Semitic root S-L-M in the name is thought to refer to either "peace" (Salam or Shalom in modern Arabic and Hebrew) or Shalim, the god of dusk in the Canaanite religion.

- c. 1850 BCE: According to the Book of Genesis, the Binding of Isaac takes place on a mountain in the land of Moriah (see Chronology of the Bible). Biblical scholars have often interpreted the location of the mountain to be Jerusalem, although this is disputed.

- c. 1700–1550 BCE: According to Manetho (via Josephus' Against Apion), the Hyksos invade the region.

Canaanite and New Kingdom Egyptian period

- c. 1550–1400 BCE: Jerusalem becomes a vassal to Egypt as the Egyptian New Kingdom reunites Egypt and expands into the Levant under Ahmose I and Thutmose I.

- c. 1330 BCE: Correspondence in the Amarna letters between Abdi-Heba, Canaanite ruler of Jerusalem (then known as Urusalim), and Amenhotep III, suggesting the city was a vassal to New Kingdom Egypt.

- 1178 BCE: The Battle of Djahy (Canaan) between Ramesses III and the Sea Peoples marks the beginning of the decline in power of the New Kingdom in the Levant during the Bronze Age collapse (depicted on the North Wall of the Medinet Habu temple and the Papyrus Harris).

- c. 1000 BCE: According to the Bible, Jerusalem is inhabited by Jebusites and is known as Jebus.

Independent Israel and Judah (House of David) period

- c. 1010 BCE: King David attacks and captures Jerusalem. Jerusalem becomes City of David and capital of the United Kingdom of Israel.[3]

- c. 962 BCE: King Solomon builds the First Temple.

- c. 931–930 BCE: Solomon dies, and the Golden Age of Israel ends. Jerusalem becomes the capital of the (southern) Kingdom of Judah led by Rehoboam after the split of the United Monarchy.

- 925 BCE: Egyptian Sack of Jerusalem – Pharaoh Sheshonk I of the Third Intermediate Period invades Canaan following the Battle of Bitter Lakes. Possibly the same as Shishak, the first Pharaoh mentioned in the Bible who captured and pillaged Jerusalem (see Bubastite Portal).

- 853 BCE: The Battle of Qarqar in which Jerusalem's forces were likely involved in an indecisive battle against Shalmaneser III of Neo-Assyria (Jehoshaphat of Judah was allied to Ahab of the Israel according to the Bible) (see Kurkh Monoliths).

- c. 850 BCE: Jerusalem is sacked by Philistines, Arabs and Ethiopians, who looted King Jehoram's house, and carried off all of his family except for his youngest son Jehoahaz.

- c. 830 BCE: Hazael of Aram Damascus conquers most of Canaan. According to the Bible, Jehoash of Judah gave all of Jerusalem's treasures as a tribute, but Hazael proceeded to destroy "all the princes of the people" in the city.

- 786 BCE: Jehoash of Israel sacks the city, destroys the walls and takes Amaziah of Judah prisoner.

- c. 740 BCE: Assyrian inscriptions record military victories of Tiglath Pileser III over Uzziah of Judah.

Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian Empires period

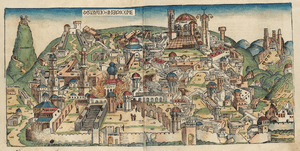

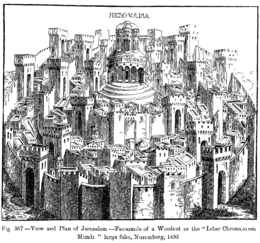

Illustration from the Nuremberg Chronicle of the destruction of Jerusalem under the Babylonian rule

- 733 BCE: According to the Bible, Jerusalem becomes a vassal of the Neo-Assyrian Empire[6][7] after Ahaz of Judah appeals to Tiglath Pileser III of the Neo-Assyrian Empire to protect the city from Pekah of Israel and Rezin of Aram. Tiglath Pileser III subsequently conquers most of the Levant. At around this time, the Siege of Gezer, 20 miles west of Jerusalem, is recorded on a stone relief at the Assyrian royal palace in Nimrud.

- c. 712 BCE: The Siloam Tunnel is built in order to keep water from the Gihon Spring inside the city. According to the Bible the tunnel was built by King Hezekiah in preparation for a siege by the Assyrians, along with an expansion of Jerusalem's fortifications across the Tyropoeon Valley to enclose the hill today known as Mount Zion.[8]

- 712 BCE: Assyrian Siege of Jerusalem – Jerusalem pays further tribute to the Neo-Assyrian Empire after the Neo-Assyrian King Sennacherib laid siege to the city.

- c. 670 BCE: Manasseh, the ruler of Jerusalem, is brought in chains to the Assyrian king, presumably for suspected disloyalty.[9]

- c. 627 BCE: The death of Ashurbanipal and the successful revolt of Nabopolassar replaces the Neo-Assyrian Empire with the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

- 609 BCE: Jerusalem becomes part of the Empire of the Twenty-sixth dynasty of Egypt after Josiah of Judah is killed by the army of Pharaoh Necho II at the Battle of Megiddo. Josiah's son Jehoahaz of Judah is deposed by the Egyptians and replaced as ruler of Jerusalem by his brother Jehoiakim.

- 605 BCE: Jerusalem switches its tributary allegiance back to the Neo-Babylonians after Necho II is defeated by Nebuchadnezzar II at the Battle of Carchemish.

- 599–597 BCE: first Babylonian siege – Nebuchadnezzar II crushed a rebellion in the Kingdom of Judah and other cities in the Levant which had been sparked by the Neo-Babylonians failed invasion of Egypt in 601. Jehoiachin of Jerusalem deported to Babylon.

- 587–586 BCE: second Babylonian siege – Nebuchadnezzar II fought Pharaoh Apries's attempt to invade Judah. Jerusalem mostly destroyed including the First Temple, and the city's prominent citizens exiled to Babylon (see Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle).

- 582 BCE: Gedaliah the Babylonian governor of Judah assassinated, provoking refugees to Egypt and a third deportation.

Persian (Achaemenid) Empire period

- 539 BCE: Jerusalem becomes part of the Eber-Nari satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire after King Cyrus the Great conquers the Neo-Babylonian Empire by defeating Nabonidus at the Battle of Opis

- Cyrus the Great issues the Edict of Cyrus allowing Babylonian Jews to return from the Babylonian captivity and rebuild the Temple (Biblical sources only, see Cyrus (Bible) and The Return to Zion).[10]

- The first wave of Babylonian returnees is Sheshbazzar's Aliyah.

- The second wave of Babylonian returnees is Zerubbabel's Aliyah.

- The return of Babylonian Jews increases the schism with the Samaritans, who had remained in the region during the Assyrian and Babylonian deportations.

- 516 BCE: The Second Temple is built in the 6th year of Darius the Great.

- 458 BCE: The third wave of Babylonian returnees is Ezra's Aliyah.

- 445 BCE: The fourth and final wave of Babylonian returnees is Nehemiah's Aliyah. Nehemiah is the appointed governor of Judah, and rebuilds the Old City walls.

- 410 BCE: The Great Assembly is established in Jerusalem.

- 350 BCE: Jerusalem revolts against Artaxerxes III, along with other cities of the Levant and Cyprus. Artaxerxes III, retakes the city and burns it down in the process. Jews who supported the revolt are sent to Hyrcania on the Caspian Sea.

Classical antiquity

Hellenistic Kingdoms (Ptolemaic / Seleucid) period

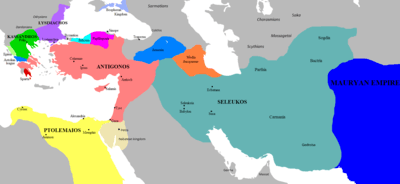

Kingdoms of the Diadochi and others before the battle of Ipsus, c. 303 BCE

The Seleucid Empire in c. 200 BCE

Hasmonean Kingdom at its greatest extent under Salome Alexandra

- 332 BCE: Jerusalem capitulates to Alexander the Great, during his six-year Macedonian conquest of the empire of Darius III of Persia. Alexander's armies took Jerusalem without complication while travelling to Egypt after the Siege of Tyre (332 BC).

- 323 BCE: The city comes under the rule of Laomedon of Mytilene, who is given control of the province of Syria following Alexander's death and the resulting Partition of Babylon between the Diadochi. This partition was reconfirmed two years later at the Partition of Triparadisus.

- 320 BCE: General Nicanor, dispatched by satrap of Egypt Ptolemy I Soter and founder of the Ptolemaic Kingdom, takes control of Syria including Jerusalem and captures Laomedon in the process.

- 315 BCE: The Antigonid dynasty gains control of the city after Ptolemy I Soter withdraws from Syria including Jerusalem and Antigonus I Monophthalmus invades during the Third War of the Diadochi. Seleucus I Nicator, then governor of Babylon under Antigonus I Monophthalmus, fled to Egypt to join Ptolemy.

- 312 BCE: Jerusalem is re-captured by Ptolemy I Soter after he defeats Antigonus' son Demetrius I at the Battle of Gaza. It is probable that Seleucus I Nicator, then an Admiral under Ptolemy's command, also took part in the battle, as following the battle he was given 800 infantry and 200 cavalry and immediately travelled to Babylon where he founded the Seleucid Empire.

- 311 BCE: The Antigonid dynasty regains control of the city after Ptolemy withdraws from Syria again following a minor defeat by Antigonus I Monophthalmus, and a peace treaty is concluded.

- 302 BCE: Ptolemy invades Syria for a third time, but evacuated again shortly thereafter following false news of a victory for Antigonus against Lysimachus (another of the Diadochi).

- 301 BCE: Coele-Syria (Southern Syria) including Jerusalem is re-captured by Ptolemy I Soter after Antigonus I Monophthalmus is killed at the Battle of Ipsus. Ptolemy had not taken part in the battle, and the victors Seleucus I Nicator and Lysimachus had carved up the Antigonid Empire between them, with Southern Syria intended to become part of the Seleucid Empire. Although Seleucus did not attempt to conquer the area he was due, Ptolemy's pre-emptive move led to the Syrian Wars which began in 274 BC between the successors of the two leaders.

- 219–217 BCE: The northern portion of Coele-Syria is given to the Seleucid Empire in 219 through the betrayal of Governor Theodotus of Aetolia, who had held the province on behalf of Ptolemy IV Philopator. The Seleucids advanced on Egypt, but were defeated at the Battle of Raphia (Rafah) in 217.

- 200 BCE: Jerusalem falls under the control of the Seleucid Empire following the Battle of Panium (part of the Fifth Syrian War) in which Antiochus III the Great defeated the Ptolemies.

- 175 BCE: Antiochus IV Epiphanes succeeds his father and becomes King of the Seleucid Empire. He accelerates Seleucid efforts to eradicate the Jewish religion by forcing the Jewish High Priest Onias III to step down in favour of his brother Jason, who was replaced by Menelaus three years later. He outlaws Sabbath and circumcision, sacks Jerusalem and erects an altar to Zeus in the Second Temple after plundering it.

- 167 BCE: Maccabean revolt sparked when a Seleucid Greek government representative under King Antiochus IV asked Mattathias to offer sacrifice to the Greek gods; he refused to do so, killed a Jew who had stepped forward to do so and attacked the government official that required the act.[11] Led to the guerilla Battle of Wadi Haramia.

- 164 BC 25 Kislev: The Maccabees capture Jerusalem following the Battle of Beth Zur, and rededicate the Temple (see Hanukkah). The Hasmoneans take control of part of Jerusalem, while the Seleucids retain control of the Acra (fortress) in the city and most surrounding areas.

- 160 BCE: The Seleucids retake control of the whole of Jerusalem after Judas Maccabeus is killed at the Battle of Elasa, marking the end of the Maccabean revolt.

- 145–144 BCE: Alexander Balas is overthrown at the Battle of Antioch (the capital of the Empire) by Demetrius II Nicator in alliance with Ptolemy VI Philometor of Egypt. The following year, Mithradates I of Parthia captured Seleucia (the previous capital of the Seleucid Empire), significantly weakening the power of Demetrius II Nicator throughout the remaining empire.

Hasmonean kingdom

- c. 140 BCE: The Acra is captured and later destroyed by Simon Thassi.

- 139 BCE: Demetrius II Nicator is taken prisoner for nine years by the rapidly expanding Parthian Empire after defeat of the Seleucids in Persia. Simon Thassi travels to Rome, where the Roman Republic formally acknowledges the Hasmonean Kingdom. However the region remains a province of the Seleucid empire and Simon Thassi is required to provide troops to Antiochus VII Sidetes.

- 134 BCE: Sadducee John Hyrcanus becomes leader after his father Simon Thassi is murdered. He takes a Greek regnal name (see Hyrcania) in an acceptance of the Hellenistic culture of his Seleucid suzerains.

- 134 BCE: Seleucid King Antiochus VII Sidetes recaptures the city. John Hyrcanus opened King David's sepulchre and removed three thousand talents which he paid as tribute to spare the city (according to Josephus.[12]) John Hyrcanus remains as governor, becoming a vassal to the Seleucids

- 116 BCE: A civil war between Seleucid half-brothers Antiochus VIII Grypus and Antiochus IX Cyzicenus results in a breakup of the kingdom and the independence of certain principalities, including Judea.[13][14]

- 110 BCE: John Hyrcanus carries out the first military conquests of the independent Hasmonean kingdom, raising a mercenary army to capture Madaba and Schechem, significantly increasing the regional influence of Jerusalem.[15][16]

- c. 87 BCE: According to Josephus, following a six-year civil war involving Seleucid king Demetrius III Eucaerus, Hasmonean ruler Alexander Jannaeus crucified 800 Jewish rebels in Jerusalem.

- 73–63 BCE: The Roman Republic extends its influence into the region in the Third Mithridatic War. During the war, Armenian King Tigranes the Great takes control of Syria and prepares to invade Judea and Jerusalem but has to retreat following an invasion of Armenia by Lucullus.[17] However, this period is believed to have resulted in the first settlement of Armenians in Jerusalem.[18] According to Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi writing in c. 482 CE, Tigranes captured Jerusalem and deported Hyrcanus to Armenia, however most scholars deem this account to be incorrect.[19][20]

Early Roman period

Extent of the Roman Empire under Augustus, 30BCE – 6AD

Pompey in the Temple, 63 BCE (Jean Fouquet 1470–1475)

- 63 BCE: Roman Republic under Pompey the Great besieges and takes the city.[3] Pompey enters the temple but leaves treasure. Hyrcanus II is appointed High Priest and Antipater the Idumaean is appointed governor.

- 57–55 BCE: Aulus Gabinius, proconsul of Syria, split the former Hasmonean Kingdom into five districts of legal and religious councils known as sanhedrin based at Jerusalem, Sepphoris (Galilee), Jericho, Amathus (Perea) and Gadara.[21][22]

- 54 BCE: Crassus loots the temple, confiscating all its gold, after failing to receive the required tribute (according to Josephus).

- 45 BCE: Antipater the Idumaean is appointed Procurator of Judaea by Julius Caesar, after Julius Caesar is appointed dictator of the Roman Republic following Caesar's Civil War.

- 43 BCE: Antipater the Idumaean is killed by poison, and is succeeded by his sons Phasael and Herod.

- 40 BCE: Antigonus, son of Hasmonean Aristobulus II and nephew of Hyrcanus II, offers money to the Parthian army to help him recapture the Hasmonean realm from the Romans. Jerusalem is captured by Barzapharnes, Pacorus I of Parthia and Roman deserter Quintus Labienus. Antigonus is placed as King of Judea. Hyracanus is mutilated, Phasael commits suicide, and Herod escapes to Rome.

- 40–37 BCE: The Roman senate appoints Herod "King of the Jews" and provides him with an army. Following Roman General Publius Ventidius Bassus' defeat of the Parthians in Northern Syria, Herod and Roman General Gaius Sosius wrest Judea from Antigonus II Mattathias, culminating in the siege of the city.[23][24]

- 37–35 BCE: Herod the Great builds the Antonia Fortress, named after Mark Anthony, on the site of the earlier Hasmonean Baris.[25]

- 19 BCE: Herod expands the Temple Mount and rebuilds the Temple (Herod's Temple), including the construction of the Western Wall.

- 15 BCE: Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, son-in-law of Emperor Augustus visits Jerusalem and offers a hecatomb in the temple.[26]

- 6 BCE: John the Baptist is born in Ein Kerem to Zechariah and Elizabeth.

- 5 BCE: Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, 40 days after his birth in Bethlehem (Biblical sources only).

- 6 BCE: End of Herodian governorate in Jerusalem.

- Herod Archelaus deposed as the ethnarch of the Tetrarchy of Judea. Herodian Dynasty replaced in the newly created Iudaea province by Roman prefects and after 44 by procurators, beginning with Coponius (Herodians continued to rule elsewhere and Agrippa I and Agrippa II later served as Kings).

- Senator Quirinius appointed Legate of the Roman province of Syria (to which Judea had been "added" according to Josephus[27] though Ben-Sasson claims it was a "satellite of Syria" and not "legally part of Syria"[28]) carries out a tax census of both Syria and Judea known as the Census of Quirinius.

- Both events spark the failed revolt of Judas the Galilean and the founding of the Zealot movement, according to Josephus.

- Jerusalem loses its place as the administrative capital to Caesarea Palaestina.[29]

- 7–26 CE: Brief period of peace, relatively free of revolt and bloodshed in Judea and Galilee.[30]

- 28–30 CE: Three-year Ministry of Jesus, during which according to the bible a number of key events took place in Jerusalem, including:

Jesus at the Temple (Giovanni Paolo Pannini c. 1750)

“Flevit super illam” (He wept over it); by Enrique Simonet, 1892.

- Temptation of Christ.

- Cleansing of the Temple – Jesus drives the merchants and moneylenders from Herod's Temple.

- Meeting with Nicodemus.

- Healing the man blind from birth.

- 30 CE: Key events in the martyrdom of Jesus which according to the bible took place in Jerusalem.

- Palm Sunday (Jesus enters Jerusalem as the Messiah, while riding on a donkey).

- Last Supper.

- The Passion and Crucifixion.

- Resurrection of Jesus.

- Ascension of Jesus.

- 30 CE: The first Christian martyr (Protomartyr) Saint Stephen stoned to death following Sanhedrin trial.

- 37–40 CE: "Crisis under Gaius Caligula" – a financial crisis throughout the empire results in the "first open break" between Jews and Romans even though problems were already evident during the Census of Quirinius in 6 AD and under Sejanus before 31 AD.[31]

- 45–46 CE: After a famine in Judea Paul and Barnabas provide support to the Jerusalem poor from Antioch.

- 50 CE: The Apostles thought to have held the Council of Jerusalem, the first Christian council. May mark the first formal schism between Christianity and Judaism at which it was agreed that Christians did not need to be circumcised or alternately may represent a form of early Noahide Law.

- 57 CE: Paul of Tarsus is arrested in Jerusalem after he is attacked by a mob in the Temple[32] and defends his actions before a sanhedrin.

- 64–68 CE: Nero persecutes Jews and Christians throughout the Roman Empire.

- 66 CE: James the Just, the brother of Jesus and first Bishop of Jerusalem, is killed in Jerusalem at the instigation of the high priest Ananus ben Ananus according to Eusebius of Caesarea.[33]

The siege of Jerusalem, 70AD (David Roberts, 1850)

- 66–73 CE: First Jewish-Roman War, with the Judean rebellion led by Simon Bar Giora

- 70 CE: Siege of Jerusalem (70) Titus, eldest son of Emperor Vespasian, ends the major portion of Great Jewish Revolt and destroys Herod's Temple on Tisha B'Av. The Roman legion Legio X Fretensis is garrisoned in the city.

- The Sanhedrin is relocated to Yavne. Pharisees become dominant, and their form of Judaism evolves into modern day Rabbinic Judaism (whereas Sadducees and Essenes are no longer recorded as groups in history—see Origins of Rabbinic Judaism).

- The city's leading Christians relocate to Pella.

- c. 90–96 CE: Jews and Christians heavily persecuted throughout the Roman Empire towards the end of the reign of Domitian.

- 115–17 CE: Jews revolt against the Romans throughout the empire, including Jerusalem, in the Kitos War.

- 117 CE: Saint Simeon of Jerusalem, second Bishop of Jerusalem, was crucified under Trajan by the proconsul Atticus in Jerusalem or the vicinity.[34]

Late Roman period (Aelia Capitolina)

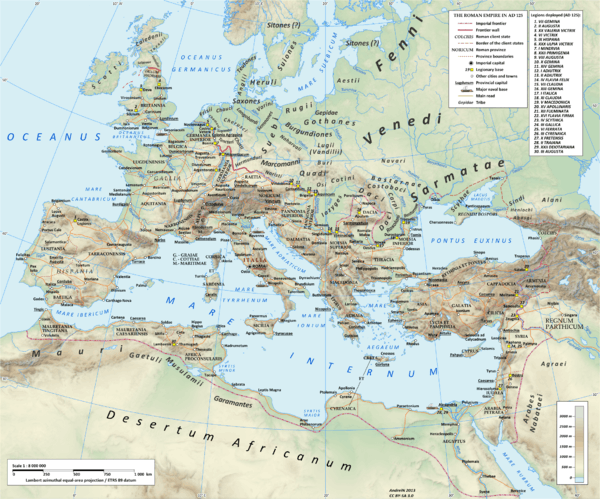

The Roman empire at its peak under Hadrian showing the location of the Roman legions deployed in 125 CE.

- 130: Emperor Hadrian visits the ruins of Jerusalem and decides to rebuild it as a city dedicated to Jupiter called Aelia Capitolina

- 131: An additional legion, Legio VI Ferrata, was stationed in the city to maintain order, as the Roman governor performed the foundation ceremony of Aelia Capitolina. Hadrian abolished circumcision (brit milah), which he viewed as mutilation.[35]

- 132–135: Bar Kokhba's revolt – Simon Bar Kokhba leads a revolt against the Roman Empire, controlling the city for three years. He is proclaimed as the Messiah by Rabbi Akiva. Hadrian sends Sextus Julius Severus to the region, who brutally crushes the revolt and retakes the city.

- 136: Hadrian formally reestablishes the city as Aelia Capitolina, and forbids Jewish and Christian presence in the city.

- c. 136–140: A Temple to Jupiter is built on the Temple Mount and a temple to Venus is built on Calvary.

- 138: Restrictions over Christian presence in the city are relaxed after Hadrian dies and Antoninus Pius becomes emperor.

- 195: Saint Narcissus of Jerusalem presides over a council held by the bishops of Palestine in Caesarea, and decrees that Easter is to be always kept on a Sunday, and not with the Jewish Passover.

- 251: Bishop Alexander of Jerusalem is killed during Roman Emperor Decius' persecution of Christians.

- 259: Jerusalem falls under the rule of Odaenathus as King of the Palmyrene Empire after the capture of Emperor Valerian by Shapur I at the Battle of Edessa causes the Roman Empire to splinter.

- 272: Jerusalem becomes part of the Roman Empire again after Aurelian defeats the Palmyrene Empire at the Battle of Emesa (Homs).

- 303: Saint Procopius of Scythopolis is born in Jerusalem.

- 312: Macarius becomes the last Bishop of Aelia Capitolina.

- 313: Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre founded in Jerusalem after Constantine I issued the Edict of Milan, legalizing Christianity throughout the Roman Empire following his own conversion the previous year.

Late Antiquity period

Byzantine period

Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476

Helena finding the True Cross (Italian manuscript, c. 825)

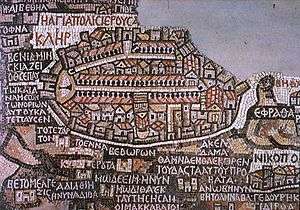

The Madaba Map depiction of sixth-century Jerusalem

- 324–25: Emperor Constantine wins the Civil Wars of the Tetrarchy (306–324) and reunites the empire. Within a few months, the First Council of Nicaea (first worldwide Christian council) confirms status of Aelia Capitolina as a patriarchate.[36] A significant wave of Christian immigration to the city begins. This is the date on which the city is generally taken to have been renamed Jerusalem.

- c. 325: The ban on Jews entering the city remains in force, but they are allowed to enter once a year to pray at the Western Wall on Tisha B'Av.

- 326: Constantine's mother Helena visits Jerusalem and orders the destruction of Hadrian's temple to Venus which had been built on Calvary. Accompanied by Macarius of Jerusalem, the excavation reportedly discovers the True Cross, the Holy Tunic and the Holy Nails.

- 333: The Eleona Basilica is built on the Mount of Olives, marking the site of the Ascension of Jesus.

- 335: First Church of the Holy Sepulchre built on Calvary.

- 347: Saint Cyril of Jerusalem delivers his Mystagogical Catecheses, instructions on the principal topics of Christian faith and practice.

- 361: Neoplatonist Julian the Apostate becomes Roman Emperor and attempts to reverse the growing influence of Christianity by encouraging other religions. As a result, Alypius of Antioch is commissioned to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem and Jews are allowed to return to the city.[37]

- 363: The Galilee earthquake of 363 together with the re-establishment of Christianity's dominance following the death of Julian the Apostate at the Battle of Samarra ends attempts to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem.

- 380: Theodosius I declares Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire. The Roman Empire later loses its western provinces, with Jerusalem continuing under the jurisdiction of the Eastern Empire (commonly known as the Byzantine Empire).

- c. 380: Tyrannius Rufinus and Melania the Elder found the first monastery in Jerusalem on the Mount of Olives.

- 386: Saint Jerome moves to Jerusalem in order to commence work on the Vulgate, commissioned by Pope Damasus I and instrumental in the fixation of the Biblical canon in the West. He later moves to Bethlehem.

- 394: John II, Bishop of Jerusalem, consecrates the Church of the Holy Zion built on the site of the Cenacle.

- 403: Euthymius the Great founds the Pharan lavra, six miles east of Jerusalem.

- 438: Empress Aelia Eudocia Augusta, wife of Theodosius II, visits Jerusalem after being encouraged by Melania the Younger.

- 451: The Council of Chalcedon confirms Jerusalem's status as a Patriarchate as one of the Pentarchy. Juvenal of Jerusalem becomes the first Patriarch of Jerusalem.[38]

- 443–60: Empress Aelia Eudocia Augusta moves to Jerusalem where she dies in 460, after being banished by Theodosius II for adultery.

- 483: Sabbas the Sanctified founds the Great Lavra, also known as Mar Saba, in the Kidron Valley.

- 540–50: Emperor Justinian I undertakes a number of building works, including the once magnificent Nea Ekklesia of the Theotokos ("the Nea") and the extension of the Cardo thoroughfare.[39]

- c. 600: Latin Pope Gregory I commissions Abbot Probus of Ravenna to build a hospital in Jerusalem to treat Latin pilgrims to the Holy Land.

- 610: The Temple Mount in Jerusalem becomes the focal point for Muslim salat (prayers), known as the First Qibla, following Muhammad's initial revelations (Wahy). (Islamic sources)

- 610: Jewish revolt against Heraclius begins in Antioch and spreads to other cities including Jerusalem.

- 614: Siege of Jerusalem (614) – Jerusalem falls to Khosrau II's Sassanid Empire led by General Shahrbaraz, during the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 602–628. Jewish leader Nehemiah ben Hushiel allied with Shahrbaraz in the battle, as part of the Jewish revolt against Heraclius, and was made governor of the city. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is burned, Patriarch Zacharias is taken prisoner, the True Cross and other relics are taken to Ctesiphon, and much of the Christian population is massacred.[40][41] Most of the city is destroyed.

- 617: Jewish governor Nehemiah ben Hushiel is killed by a mob of Christian citizens, three years after he is appointed. The Sassanids quell the uprising and appoint a Christian governor to replace him.

- 620: Muhammad's night journey (Isra and Mi'raj) to Jerusalem. (Islamic sources)

- 624: Jerusalem loses its place as the focal point for Muslim prayers to Mecca, 18 months after the Hijra (Muhammad's migration to Medina).

- c. 625: According to Sahih al-Bukhari, Muhammad ordained the Al-Aqsa Mosque as one of the three holy mosques of Islam.[42]

- 629: Byzantine Emperor Heraclius retakes Jerusalem, after the decisive defeat of the Sassanid Empire at the Battle of Nineveh (627). Heraclius personally returns the True Cross to the city.[43]

Middle Ages

Rashidun, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates period

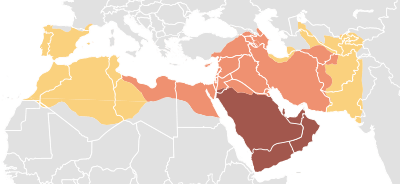

The expansion of the caliphate under the Umayyads.

Expansion under Muhammad, 622–632

Expansion during the Rashidun Caliphate, 632–661

Expansion during the Umayyad Caliphate, 661–750

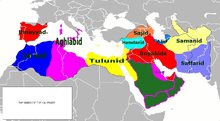

An anachronistic map of the various de facto independent emirates after the Abbasids lost their military dominance (c. 950)

- 636–37: Siege of Jerusalem (637) Caliph Umar the Great conquers Jerusalem and at the request of Jerusalem's Christian Patriarch, enters the city on foot, following the decisive defeat of the Byzantine Empire at the Battle of Yarmouk a few months earlier.[3] Patriarch Sophronius and Umar are reported to have agreed the Covenant of Umar I, which guaranteed non-Muslims freedom of religion, and under Islamic rule, for the first time since the Roman period, Jews were once again allowed to live and worship freely in Jerusalem.[44] Jerusalem becomes part of the Jund Filastin province of the Arab Caliphate.

- 638: The Armenian Apostolic Church began appointing its own bishop in Jerusalem.

- 661: Muawiyah I is ordained as Caliph of the Islamic world in Jerusalem following the assassination of Ali in Kufa, ending the First Fitna and marking the beginning of the Umayyad Empire.

- 677: According to interpretations of Maronite historian Theophilus of Edessa, Mardaites (possibly ancestors of today's Maronites) took over a swathe of land including Jerusalem on behalf of the Byzantine Emperor, who was simultaneously repelling the Umayyads in the Siege of Constantinople (674–678). However, this has been contested as a mistranslation of the words "Holy City".[45][46]

- 687–691: The Dome of the Rock is built by Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan during the Second Fitna, becoming the world's first great work of Islamic architecture.[3]

- 692: Orthodox Council in Trullo formally makes Jerusalem one of the Pentarchy (disputed by Roman Catholicism).

- 705: The Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid I builds the Masjid al-Aqsa.

- 730–749: John of Damascus, previously chief adviser to Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, moves to the monastery Mar Saba outside Jerusalem and becomes the major opponent of the First Iconoclasm through his theological writings.

- 744–750: Riots in Jerusalem and other major Syrian cities during the reign of Marwan II, quelled in 745–46. The Umayyad army is subsequently defeated in 750 at the Battle of the Zab by the Abbasids, who take control of the entire empire including Jerusalem. Marwan II flees via Jerusalem but is assassinated in Egypt.

- 793–96: Qaysi–Yamani war (793–96).

- 797: First embassy sent from Charlemagne to Caliph Harun al-Rashid as part of the attempted Abbasid–Carolingian alliance.[47] Harun al-Rashid is reported to have offered the custody of the Holy places in Jerusalem to Charlemagne. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was restored and the Latin hospital was enlarged and placed under the control of the Benedictines.[48]

- 799: Charlemagne sent another mission to Patriarch George of Jerusalem[49]

- 801: Sufi saint Rabia Al-Adawiyya dies in Jerusalem.

- 813: Caliph Al-Ma'mun visits Jerusalem and undertakes extensive renovations to the Dome of the Rock.

- 878: Ahmad ibn Tulun, ruler of Egypt and founder of the Tulunid dynasty, conquers Jerusalem and most of Syria, four years after declaring Egypt's independence from the Abbasid court in Baghdad.

- 881: Patriarch Elias III of Jerusalem corresponded with European rulers asking for financial donations, including Holy Roman Emperor and King of West Francia Charles the Fat and Alfred the Great of England.

- 904: The Abbasids regain control of Jerusalem after invading Syria, and the army of Tulunid Emir Harun retreats to Egypt where the Tulunids were defeated the following year.

- 939/944: Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikhshid, governor of Abbasid Egypt and Palestine, is given the title al-Ikhshid by Abbasid Caliph Ar-Radi, and in 944 is named hereditary governor of his lands.

- 946: Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikhshid dies. Abu al-Misk Kafur becomes de facto ruler of the Ikhshidid lands.

- 951–978: Estakhri, Traditions of Countries and Ibn Hawqal, The Face of the Earth write of Jund Filistin "Its capital and largest town is Ramla, but the Holy City of Jerusalem comes very near this last in size", and of Jerusalem: "It is a city perched high on the hills: and you have to go up to it from all sides. In all Jerusalem there is no running water, excepting what comes from springs, that can be used to irrigate the fields, and yet it is the most fertile portion of Filastin."[50]

- 966: Al-Muqaddasi leaves Jerusalem to begin his 20-year geographical study, writing in detail about Jerusalem in his Description of Syria, Including Palestine[50]

- 968: Abu al-Misk Kafur dies and is also buried in Jerusalem. The Ikhshidid government divides and the Fatimids prepare for invasion of Egypt and Palestine.

Fatimid Caliphate period

The Fatimid Caliphate at its greatest extent

- 969: The Ismaili Shia Fatimids under General Jawhar al-Siqilli conquer the Ikhshidid domains of the Abbasid empire including Jerusalem, following a treaty guaranteeing the local Sunnis freedom of religion.

- 975: Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimiskes's second Syrian campaign takes Emesa, Baalbek, Damascus, Tiberias, Nazareth, Caesarea, Sidon, Beirut, Byblos and Tripoli, but is defeated en route to Jerusalem. The emperor dies suddenly in 976 on his return from the campaign.

- 1009: Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim orders destruction of churches and synagogues in the empire, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

- 1021: Caliph Ali az-Zahir undertakes extensive renovations to the Dome of the Rock.

- 1023–41: Anushtakin al-Dizbari is the governor of Palestine and Syria, and defeats the Bedouin revolt of 1024–29. Fifteen years later, in 1057, his body was ceremonially transferred to Jerusalem by Caliph al-Mustansir for reburial.[51]

- 1030: Caliph Ali az-Zahir authorizes the rebuilding of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and other Christian churches in a treaty with Byzantine Emperor Romanos III Argyros.

- 1042: Byzantine Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos pays for the restoration of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, authorized by Caliph Ma'ad al-Mustansir Billah. Al-Mustansir authorizes a number of other Christian buildings, including the Muristan hospital, church and monastery built by a group of Amalfi merchants in c. 1050.

- 1054: Great Schism – the Patriarch of Jerusalem joined the Eastern Orthodox Church, under the jurisdiction of Constantinople. All Christians in the Holy Land came under the jurisdiction of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, setting in place a key cause of the Crusades.

- 1073: Jerusalem is captured by Malik-Shah I's Great Seljuq Empire under Emir Atsiz ibn Uvaq, who was advancing south into the weakening Fatimid Empire following the decisive defeat of the Byzantine army at the Battle of Manzikert two years previously and a devastating six-year famine in Egypt between 1067 and 1072.[52]

- 1077: Jerusalem revolts against the rule of Emir Atsiz ibd Uvaq while he is fighting the Fatimid Empire in Egypt. On his return to Jerusalem, Atsiz re-takes the city and massacres the local population.[53] As a result, Atsiz is executed by Tutush I, governor of Syria under his brother, Seljuk leader Malik-Shah I. Tutush I appoints Artuq bin Ekseb, later founder of the Artuqid dynasty, as governor.

- 1091–95: Artuq bin Ekseb dies in 1091, and is succeeded as governor by his sons Ilghazi and Sokmen. Malik Shah dies in 1092, and the Great Seljuk Empire splits into smaller warring states. Control of Jerusalem is disputed between Duqaq and Radwan after the death of their father Tutush I in 1095. The ongoing rivalry weakens Syria.

- 1095–96: Al-Ghazali lives in Jerusalem.

- 1095: At the Council of Clermont Pope Urban II calls for the First Crusade.

- 1098: Fatimid Regent Al-Afdal Shahanshah reconquers Jerusalem from Artuq bin Ekseb's sons Ilghazi and Sokmen.

First Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1187)

Crusader states in 1180

The capture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders on 15 July 1099

1. The Holy Sepulchre, 2. The Dome of the Rock, 3. Ramparts

1. The Holy Sepulchre, 2. The Dome of the Rock, 3. Ramparts

A woodcut of Jerusalem in the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493

- 1099: Siege of Jerusalem (1099) – First Crusaders capture Jerusalem and slaughter most of the city's Muslim and Jewish inhabitants. The Dome of the Rock is converted into a Christian church. Godfrey of Bouillon becomes Protector of the Holy Sepulchre.[54]

- 1100: Dagobert of Pisa becomes Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem. Godfrey of Bouillon promises to turn over the rule of Jerusalem to the Papacy once the crusaders capture Egypt. The invasion of Egypt did not occur as Godfrey died shortly thereafter. Baldwin I was proclaimed the first King of Jerusalem after politically outmanoeuvering Dagobert.

- 1104: The Al-Aqsa Mosque becomes the Royal Palace of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

- 1112: Arnulf of Chocques becomes Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem for the second time and prohibits non-Catholic worship at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

- 1113: The foundation of the Knights Hospitaller by Gerard Thom at the Muristan Christian hospice in Jerusalem is confirmed by a Papal Bull from Pope Paschal II.

- 1119: Hugues de Payens and Godfrey de Saint-Omer found the Knights Templar in the Al Aqsa Mosque.

- 1123: Pactum Warmundi alliance established between the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Republic of Venice.

- 1131: Melisende became Queen of Jerusalem, later acting as regent for her son between 1153 and 1161 while he was on campaign. She was the eldest daughter of King Baldwin II of Jerusalem, and the Armenian princess Morphia of Melitene.

- 1137: Zengi defeats Fulk of Jerusalem at the Battle of Ba'rin. Fulk was trapped in Ba'rin Castle, but released by Zengi on payment of a ransom.

- 1138: St Anne's Church is built by Arda of Armenia, widow of Baldwin I of Jerusalem.

- 1149: New Church of the Holy Sepulchre built.

- 1141–73: Jerusalem is visited by Yehuda Halevi (1141), Maimonides (1165), Benjamin of Tudela (1173).

- 1160: According to Benjamin of Tudela, messianic claimant David Alroy called his followers in Baghdad to join him on a mission to Jerusalem.

- 1170–84: William of Tyre writes his magnum opus Historia Hierosolymitana.

Ayyubid period and Second Crusader Kingdom

The Crusader defeat at the Battle of Hattin leads to the end of the First Crusader Kingdom (1099–1187). During the Second Crusader Kingdom (1192–1291), the Crusaders can only gain a foothold in Jerusalem on a limited scale, twice through treaties (access rights in 1192 after the Treaty of Jaffa; partial control 1229–39 after the Treaty of Jaffa and Tell Ajul), and again for a last time between 1241 and 1244.[55]

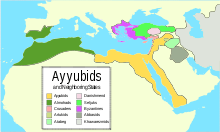

Jerusalem under the Ayyubid dynasty after the death of Saladin, 1193

The Bahri Mamluk Dynasty 1250–1382

- 1187: Siege of Jerusalem (1187) – Saladin captures Jerusalem from the Crusaders, after Battle of the Horns of Hattin. Allows Jewish and Orthodox Christian settlement. The Dome of the Rock is converted to an Islamic centre of worship again.

- 1192: Third Crusade under Richard the Lionheart fails to recapture Jerusalem, but ends with the Treaty of Ramla in which Saladin agreed that Western Christian pilgrims could worship freely in Jerusalem.

- 1193: Mosque of Omar built under Saladin outside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, commemorating Umar the Great's decision to pray outside the church so as not to set a precedent and thereby endanger the Church's status as a Christian site.

- 1193: The Moroccan Quarter is established.

- 1206: Ibn Arabi makes a pilgrimage to the city.

- 1212: 300 Rabbis from England and France settle in Jerusalem.

- 1219: Despite having rebuilt the walls during the Third Crusade, Al-Mu'azzam, Ayyubid Emir of Damascus, destroys the city walls to prevent the Crusaders from capturing a fortified city.

- 1219: Jacques de Vitry writes his magnum opus Historia Hierosolymitana.

- 1229–44: From 1229 to 1244, Jerusalem peacefully reverted to Christian control as a result of a 1229 Treaty agreed between the crusading Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and al-Kamil, the Ayyubid Sultan of Egypt, that ended the Sixth Crusade.[56][57][58][59][60] The Ayyubids retained control of the Muslim holy places, and Arab sources suggest that Frederick was not permitted to restore Jerusalem's fortifications.

- 1239: An-Nasir Dawud, Ayyubid Emir of Kerak, briefly occupies the city and destroys its fortifications before withdrawing to Kerak.

- 1240–44: An-Nasir Dawud competes with his cousin As-Salih Ayyub, who had allied with the Crusaders, for control of the region.

- 1244: Siege of Jerusalem (1244) – In order to permanently retake the city from rival breakaway Abbasid rulers who had allied with the Crusaders, As-Salih Ayyub summoned a huge mercenary army of Khwarezmians, who were available for hire following the defeat of the Khwarazm Shah dynasty by the Mongols ten years earlier.[61] The Khwarezmians could not be controlled by As-Salih Ayyub, and destroyed the city. A few months later, the two sides met again at the decisive Battle of La Forbie, marking the end of the Crusader influence in the region.

- 1246: The Ayyubids regain control of the city after the Khwarezmians are defeated by Al-Mansur Ibrahim at Lake Homs.

- 1248–50: The Seventh Crusade, launched in reaction to the 1244 destruction of Jerusalem, fails after Louis IX of France is defeated and captured by Ayyubid Sultan Turanshah at the Battle of Fariskur in 1250. The Mamluk Sultanate is indirectly created in Egypt as a result, as Turanshah is killed by his Mamluk soldiers a month after the battle and his stepmother Shajar al-Durr becomes Sultana of Egypt with the Mamluk Aybak as Atabeg. The Ayyubids relocate to Damascus, where they continue to control the rump of their empire including Jerusalem for a further ten years.

Bahri Mamluk and Burji Mamluk periods

- 1260: The Army of the Mongol Empire reaches Palestine for the first time:

- Jerusalem raided as part of the Mongol raids into Palestine under Nestorian Christian general Kitbuqa. Hulagu Khan sends a message to Louis IX of France that Jerusalem remitted to the Christians under the Franco-Mongol Alliance.

- Hulagu Khan returns to Mongolia following the death of Mongke, leaving Kitbuqa and a reduced army to fight the Battle of Ain Jalut, north of Jerusalem. The Mongols are defeated by the Egyptian Mamelukes under Qutuz and Baibars.[62]

- 1267: Nachmanides goes to Jerusalem and prays at the Western Wall. Reported to have found only two Jewish families in the city.

- 1300: Further Mongol raids into Palestine under Ghazan and Mulay. Jerusalem held by the Mongols for four months (see Ninth Crusade). Hetham II, King of Armenia, was allied to the Mongols and is reported to have visited Jerusalem where he donated his sceptre to the Armenian Cathedral.

- 1307: Marino Sanuto the Elder writes his magnum opus Historia Hierosolymitana.

- 1318–20: Regional governor Sanjar al-Jawli undertook renovations of the city, including building the Jawliyya Madrasa.

- 1328: Tankiz, the Governor of Damascus, undertook further renovations including of the al-Aqsa Mosque and building the Tankiziyya Madrasa.

- 1340: The Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem builds a wall around the Armenian Quarter.

- 1347: The Black Death sweeps Jerusalem and much of the rest of the Mamluk Sultanate.

- 1377: Jerusalem and other cities in Mamluk Syria revolt, following the death of Al-Ashraf Sha'ban. The revolt was quelled and a coup d'etat is staged by Barquq in Cairo in 1382, founding the Mamluk Burji dynasty.

- 1392–93: Henry IV of England makes a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

- 1482: The visiting Dominican priest Felix Fabri described Jerusalem as "a collection of all manner of abominations". As "abominations" he listed Saracens, Greeks, Syrians, Jacobites, Abyssinians, Nestorians, Armenians, Gregorians, Maronites, Turcomans, Bedouins, Assassins, a sect possibly Druzes, Mamelukes, and "the most accursed of all", Jews. Only the Latin Christians "long with all their hearts for Christian princes to come and subject all the country to the authority of the Church of Rome".

- 1496: Mujir al-Din al-'Ulaymi writes The Glorious History of Jerusalem and Hebron.

Early modern period

Early Ottoman period

The Ottoman Empire in 1683, showing Jerusalem

- 1516: The Ottoman Empire replaces the Mamluks in Palestine after Sultan Selim I defeats the last Mamluk Sultan Al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghawri at the Battle of Marj Dabiq (Aleppo) and the Battle of Yaunis Khan (Gaza).

- 1517: Sultan Selim I makes a pilgrimage to Jerusalem on his way to the final defeat of the Mamluks at the Battle of Ridaniya (Cairo). Selim proclaims himself Caliph of the Islamic world.

- 1518: Abu Ghosh clan sent to Jerusalem to restore order and to secure the pilgrimage route between Jaffa and Jerusalem.

- 1535–38: Suleiman the Magnificent rebuilds walls around Jerusalem.[63]

- 1541: The Golden Gate is permanently sealed.

- 1546: On 14 January a damaging earthquake shook the Palestine region. The epicentre of the earthquake was in the Jordan River in a location between the Dead Sea and the Sea of Galilee. The cities of Jerusalem, Hebron, Nablus, Gaza and Damascus were damaged.[64]

- 1555: Father Boniface of Ragusa, Franciscan Custodian of the Holy Land, repairs the Tomb of Christ (the Aedicula) in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This was the first time the tomb was opened since the visit of Saint Helena in 326. It was carried out with the permission of Pope Julius III and Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, and with funds from Philip II of Spain who claimed the title King of Jerusalem.[65]

- 1604: First Protectorate of missions agreed under the Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, in which Ahmad I agreed that the subjects of Henry IV of France were free to visit the Holy Places of Jerusalem. French missionaries begin to travel to Jerusalem and other major Ottoman cities.

- 1624: Following the Battle of Anjar, Druze prince Fakhr-al-Din II is appointed the "Emir of Arabistan" by the Ottomans to govern the region from Aleppo to Jerusalem. He toured his new provinces in the same year.[66]

- 1663–65: Sabbatai Zevi, founder of the Sabbateans, preaches in Jerusalem before travelling back to his native Smyrna where he proclaimed himself the Messiah.

- 1672: Synod of Jerusalem.

- 1700: Judah the Pious with 1000 followers settle in Jerusalem.

- 1703–05: The Naqib al-Ashraf Revolt, during which the city's inhabitants revolted against heavy taxation. It was ultimately put down two years later by Jurji Muhammad Pasha.[67]

- 1705: Restrictions imposed against the Jews.

- 1744: The English reference book Modern history or the present state of all nations stated that "Jerusalem is still reckoned the capital city of Palestine".[68]

- 1757 Ottoman firman is issued regarding the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

- 1771–72: The renegade Christian Mamluk ruler of Egypt Ali Bey al-Kabir temporarily took control of Jerusalem with 30,000 troops, together with Zahir al-Umar and Russia (who had also instigated a Greek revolt as part of the Russo-Turkish War (1768–74)).

- 1774: The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca is signed between Catherine the Great and Sultan Abdul Hamid I giving Russia the right to protect all Christians in the Ottoman Empire.(Same rights previously given to France (1535) and England.)

- 1798: Patriarch Anthemus of Jerusalem contended that the Ottoman Empire was part of God's divine providence to protect the Orthodox Church from Roman Catholicism and Western secularism.

- 1799: Napoleon's unsuccessful campaign in Egypt and Syria intends to capture Jerusalem, but is defeated at the Siege of Acre.

Modern era

Decline of the Ottoman Empire period

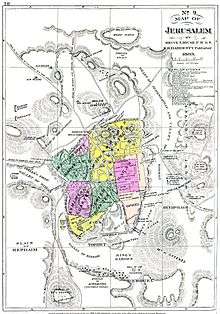

Map of Jerusalem in 1883

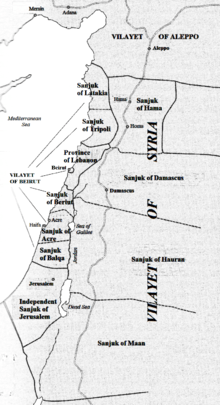

"Independent" Vilayet of Jerusalem shown within Ottoman administrative divisions in the Levant after the reorganisation of 1887–88

- 1821: Greek War of Independence begins after Metropolitan bishop Germanos of Patras proclaimed a national uprising against the Ottoman empire at the Monastery of Agia Lavra. Jerusalem's Christian population, who were estimated to make up around 20 percent of the city's total[69] (with the majority being Greek Orthodox), were forced by the Ottoman authorities to relinquish their weapons, wear black and help improve the city's fortifications.

- 1825–26: Antitax rebellion takes control of the citadel and expels the city's garrison. The rebellion is put down by Abdullah Pasha.

- 1827: First visit by Sir Moses Montefiore.

- 1831: Wali Muhammad Ali of Egypt conquers the city following Sultan Mahmud II's refusal to grant him control over Syria as compensation for his help fighting the Greek War of Independence. The invasion led to the First Turko-Egyptian War.

- 1833: Armenians establish the first printing press in the city.

- 1834: Jerusalem revolts against conscription under the rule of Muhammad Ali of Egypt during the 1834 Arab revolt in Palestine.

- 1838–57: The first European consulates are opened in the city (e.g. Britain 1838).

- 1839–40: Rabbi Judah Alkalai publishes "The Pleasant Paths" and "The Peace of Jerusalem", urging the return of European Jews to Jerusalem and Palestine.

- 1840: A firman is issued by Ibrahim Pasha forbidding Jews to pave the passageway in front of the Western Wall. It also cautioned them against "raising their voices and displaying their books there."

- 1840: The Ottoman Turks retake the city—with help from the English (Lord Palmerston).

- 1841: The British and Prussian Governments as well as the Church of England and the Evangelical Church in Prussia establish a joint Protestant Bishopric in Jerusalem, with Michael Solomon Alexander as the first Protestant bishop in Jerusalem.

- 1847: Giuseppe Valerga is appointed as the first Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem since the Crusades.

- 1852: Sultan Abdülmecid I published a firman setting out the rights and responsibility of each community at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The firman is known as the "Status quo" and its protocol is still in force today.

- 1853–54: Under military and financial pressure from Napoleon III, Sultan Abdulmecid I accepts a treaty confirming France and the Roman Catholic Church as the supreme authority in the Holy Land with control over the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This decision contravened the 1774 treaty with Russia, and led to the Crimean War.

- 1854: Albert Cohn makes his first visit to the city, at the request of the Consistoire Central des Israélites de France.

- 1857–90: The Batei Mahse, two-storey buildings, are built in the Jewish Quarter by the Batei Mahse Company, an organization of Dutch and German Jews[70]

- 1860: The first Jewish neighbourhood (Mishkenot Sha'ananim) is built outside the Old City walls, in an area later known as Yemin Moshe, by Sir Moses Montefiore and Judah Touro, as part of the process to "leave the walls" (Hebrew: היציאה מן החומות).[71][72]

- 1862: Moses Hess publishes Rome and Jerusalem, arguing for a Jewish homeland in Palestine centred on Jerusalem.

- 1862: The eldest son of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert Edward (later Edward VII), visited Jerusalem.[73]

- 1868: Mahane Israel becomes the second Jewish neighbourhood outside the walls after it was built by Maghrebi Jews from the Old City.

- 1869: Nahalat Shiv'a becomes the third Jewish neighbourhood outside the walls, built as a cooperative effort.

- 1872: Beit David becomes the fourth Jewish neighbourhood outside the walls, built as an almshouse.

- 1873–75: Mea She'arim is built (the fifth Jewish neighbourhood outside the walls).

- 1877: Jerusalem representative Yousef al-Khalidi is appointed President of the Chamber of Deputies in the short-lived first Ottoman parliament following the accession of Abdul Hamid II and the declaration of the Kanun-ı Esasî.

- 1881: The American Colony is established by Chicago natives Anna and Horatio Spafford.

- 1881: Eliezer Ben-Yehuda moves to Jerusalem to begin his development of modern Hebrew to replace the languages used by Jews who made aliyah from various regions of the world.

- 1882: The First Aliyah results in 25,000–35,000 Zionist immigrants entering the Palestine region.

- 1886: Church of Maria Magdalene is built by the Russian Orthodox Church.

- 1887–88: Ottoman Palestine divided into the districts of Jerusalem, Nablus and Acre—Jerusalem District is "autonomous", i.e. attached directly to Istanbul.

- 1897: First Zionist Congress at which Jerusalem was discussed as the possible capital of a future Jewish state. In response, Abdul Hamid II initiates policy of sending members of his own palace staff to govern province of Jerusalem.

- 1898: German Emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II visits the city to dedicate the Lutheran Church of the Redeemer. He meets Theodor Herzl outside the city walls.

- 1899: St. George's Cathedral is built, becoming the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Jerusalem of the Episcopal Church in Jerusalem and the Middle East.

- 1901: Ottoman restrictions on Zionist immigration to and land acquisition in Jerusalem district take effect.

- 1906: Bezalel Academy of Art and Design is founded.

- 1908: Young Turk Revolution reconvenes the Ottoman parliament, to which the Jerusalem district sends two members.

British Mandate period

Zones of French and British influence and control proposed in the Sykes-Picot Agreement

General Allenby enters Jerusalem on foot out of respect for the Holy City, 11 December 1917

- 1917: The Ottomans are defeated at the Battle of Jerusalem during the First World War. The British Army's General Allenby enters Jerusalem on foot, in a reference to the entrance of Caliph Umar in 637. The Balfour Declaration had been issued just a month before.

- 1918: The Pro-Jerusalem Society is founded by Sir Ronald Storrs, the British Governor of Jerusalem, and Charles Robert Ashbee, an architect.[74] They repair the city walls, and institute a number of key city planning laws including that all buildings must be faced with Jerusalem stone.

- 1918: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI) is founded (inaugurated in 1925) on Mount Scopus on the land owned by the Jewish National Fund.

- 1918–20: Jerusalem is under British military administration.

- 1920: Nabi Musa Riots in and around the Old City of Jerusalem mark the first large-scale skirmish of the Arab-Israeli Conflict.

- 1921: Hajj Mohammad Amin al-Husayni is appointed Grand Mufti of Jerusalem.

- 1923: The first lecture is delivered by the first president of World Union of Jewish Students (WUJS), Albert Einstein.

- 1924: Jacob Israël de Haan was assassinated in Jerusalem by the Haganah, becoming the first victim of Zionist political violence.

- 1929: 1929 Palestine riots sparked by a demonstration organized by Joseph Klausner's Committee for the Western Wall.[75][76][77][78]

- 1932: King David Hotel is opened. The first issue of The Palestine Post is published.

- 1946: King David Hotel is blown up by militant Irgun Tzvai-Leumi Zionists, killing 91 people including 28 British government officials. It remains the deadliest explosion in the Arab-Israeli Conflict to date.[79]

- 1947 November 29: 1947 UN Partition Plan calls for internationalization of Jerusalem as a "corpus separatum" (UN General Assembly Resolution 181).

Partition between Israel and Jordan

- 1947–48: 1947–1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine.

- 1948: 1948 Arab–Israeli War.

- 6 January: Semiramis Hotel bombing.

- 9 April: Deir Yassin Massacre.

- 13 May: Hadassah medical convoy massacre.

- 14 May: The term of the British Mandate ends and the British forces leave the city.[80]

- 14 May: The State of Israel is established at 4 pm.

- 22 May: American Consul General Thomas C. Wasson is killed on Wauchope Street by an unknown assassin.

- 27 May: The Arab Legion destroys the Hurva Synagogue.

- 28 May: The Jewish Quarter of the Old City falls to Arab Legion under Glubb Pasha. The Legion destroys all remaining synagogues. Mordechai Weingarten discusses surrender terms with Abdullah el Tell.

- 26 July: West Jerusalem is proclaimed territory of Israel.

- 17 September: Folke Bernadotte, the United Nations' mediator in Palestine and the first official mediator in the UN's history, is killed by Lehi assassins.

- 1949: Jerusalem is proclaimed the capital of Israel. The Knesset moves to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv. Jordan prevents access to the Western Wall and Mount Scopus, in violation of the 1949 Armistice Agreements.

- 1951: King Abdullah I of Jordan is assassinated by Arab extremists on the Temple Mount.

- 1953: Establishment of Yad Vashem.

- 1964: Pope Paul VI visits Israel, becoming the first pope in one thousand years to visit the Holy Land, but performs a ceremony at Mount Zion without visiting the Old City of Jerusalem. His meeting with Patriarch Athenagoras I of Constantinople led to the rescinding of the excommunications of the 1054 Great Schism.

- 1966: Inauguration of new Knesset building. Israel Museum and Shrine of the Book are established.

Israeli period

The Temple Mount as it appears today. The Western Wall is in the foreground with the Dome of the Rock in the background

- 1967 5–11 June: The Six-Day War.

- 6 June: The Battle of Ammunition Hill takes place in the northern part of Jordanian controlled East Jerusalem.

- 7 June: The Old City is captured by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

- 10 June: The Moroccan Quarter including 135 houses and the Al-Buraq mosque is demolished, creating a plaza in front of the Western Wall.

- 28 June: Israel declares Jerusalem unified and announces free access to holy sites of all religions.

- 1968: Israel conquers the Jewish Quarter, confiscating 129 dunams (0.129 km2) of land which had made up the Jewish Quarter before 1948.[81] evicting 6000 residents and 437 shops.[82]

- 1969: Denis Michael Rohan, an Australian Protestant extremist, burns a part of the al-Aqsa Mosque.

- 1977: Anwar Sadat, President of Egypt, visits Jerusalem and addresses the Knesset.

- 1978: World Union of Jewish Students (WUJS) headquarters moves from London to Jerusalem.

- 1980: The Jerusalem Law is enacted leading to UN Security Council Resolution 478 (it states that the Council will not recognize this law).

- 2000: Pope John Paul II becomes the first Latin Pope to visit Jerusalem, and prays at the Western Wall.

- 2000: Final Agreement between Israel and Palestinian Authority is not achieved at the 2000 Camp David Summit, with the status of Jerusalem playing a central role in the breakdown of talks.

- 2000: The Second Intifada (also known as Al-Aqsa Intifada) begins two months after the end of the Camp David Summit—Ariel Sharon's visit to the Temple Mount is reported to have been a relevant factor in the uprising.

- 2008: Israeli Sephardic Religious Party, Shas, refuses to form part of the government without a guarantee that there will be no negotiations that will lead to a partition of Jerusalem.

- 2017: December: US president, Donald Trump, recognizes Jerusalem as the capital of Israel; this sparks protest by many Palestinians and other Muslims in the region.[83]

- 2018: The United States, followed by Guatemala and Paraguay become the first three countries to open embassies to Israel in Jerusalem.[84]

Graphical overview of Jerusalem's historical periods

See also

- List of people from Jerusalem

- Timeline of the history of the region of Palestine

- Timeline of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Time periods in the Palestine region

- Timelines of cities in Israel: Haifa, Tel Aviv (+ Jaffa)

- Timelines of cities in Palestinian territories: Hebron

References

Notes

- ↑ Steckoll, Solomon H., The gates of Jerusalem, Frederick A. Praeger, New York, 1968, preface

- ↑ "Do We Divide the Holiest Holy City?". Moment Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 June 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2008. . According to Eric H. Cline's tally in Jerusalem Besieged.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Slavik, Diane. 2001. Cities through Time: Daily Life in Ancient and Modern Jerusalem. Geneva, Illinois: Runestone Press, p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8225-3218-7

- ↑ Mazar, Benjamin. 1975. The Mountain of the Lord. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., p. 45. ISBN 0-385-04843-2

- ↑ Jane M. Cahill (2003). "Jerusalem at the time of the United Monarchy". In Vaughn, Andrew; Killebrew, Ann. E. Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period. Society of Biblical Literature. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-58983-066-0.

- ↑ Crouch, C. L. (1 October 2014). Israel and the Assyrians: Deuteronomy, the Succession Treaty of Esarhaddon, and the Nature of Subversion. SBL Press. ISBN 978-1-62837-026-3.

Judah's reason(s) for submitting to Assyrian hegemony, at least superficially, require explanation, while at the same time indications of its read-but-disguised resistance to Assyria must be uncovered... The political and military sprawl of the Assyrian empire during the late Iron Age in the southern Levant, especially toward its outer borders, is not quite akin to the single dominating hegemony envisioned by most discussions of hegemony and subversion. In the case of Judah it should be reiterated that Judah was always a vassal state, semi-autonomous and on the periphery of the imperial system, it was never a fully-integrated provincial territory. The implications of this distinction for Judah's relationship with and experience of the Assyrian empire should not be underestimated; studies of the expression of Assyria's cultural and political powers in its provincial territories and vassal states have revealed notable differences in the degree of active involvement in different types of territories. Indeed, the mechanics of the Assyrian empire were hardly designed for direct control over all its vassals' internal activities, provided that a vassal produced the requisite tribute and did not provoke trouble among its neighbors, the level of direct involvement from Assyria remained relatively low. For the entirety of its experience of the Assyrian empire, Judah functioned as a vassal state, rather than a province under direct Assyrian rule, thereby preserving at least a certain degree of autonomy, especially in its internal affairs. Meanwhile, the general atmosphere of Pax Assyriaca in the southern Levant minimized the necessity of (and opportunities for) external conflict. That Assyrians, at least in small numbers, were present in Judah is likely - probably a qipu and his entourage who, if the recent excavators of Ramat Rahel are correct, perhaps resided just outside the capital - but there is far less evidence than is commonly assumed to suggest that these left a direct impression of Assyria on this small vassal state... The point here is that, despite the wider context of Assyria's political and economic power in the ancient Near East in general and the southern Levant in particular, Judah remained a distinguishable and semi-independent southern Levantine state, part of but not subsumed by the Assyrian empire and, indeed, benefitting from it in significant ways.

- ↑ Chronology of the Israelite Tribes from The History Files (historyfiles.co.uk)

- ↑ Ben-Dov, Meir. 1985. In the Shadow of the Temple. New York, New York: Harper & Row Publishers, Inc., pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-06-015362-8

- ↑ Bright, John (1980). A History of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-664-22068-6.

- ↑ http://studentreader.com/jerusalem/#Edict-of-Cyrus Student Reader Jerusalem: "When Cyrus captured Babylon, he immediately issued the Edict of Cyrus, a decree that those who had been exiled by the Babylonians could return to their homelands and start rebuilding."

- ↑ "Maccabean Revolt". Virtualreligion.net. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ Josephus The Jewish Wars (1:60)

- ↑ Barthold Georg Niebuhr; Marcus Carsten Nicolaus von Niebuhr (1852). Lectures on Ancient History. Taylor, Walton, and Maberly. p. 465.

- ↑ "Josephus, chapter 10". Christianbookshelf.org. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ Encyclopaedic dictionary of the Bible, Volume 5, William George Smith. Concept Publishing Company. 1893.

- ↑ Sievers, 142

- ↑ Martin Sicker (2001). Between Rome and Jerusalem: 300 Years of Roman-Judaean Relations. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-275-97140-3.

- ↑ "Armenians of Jerusalem Launch Project To Preserve History and Culture". Pr-inside.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ Aram Topchyan; Aram Tʻopʻchʻyan (2006). The Problem of the Greek Sources of Movses Xorenacʻi's History of Armenia. Isd. ISBN 978-90-429-1662-3.

- ↑ Jacob Neusner (1997). A History of the Jews in Babylonia. 2. Brill Archive. p. 351.

- ↑ "And when he had ordained five councils (συνέδρια), he distributed the nation into the same number of parts. So these councils governed the people; the first was at Jerusalem, the second at Gadara, the third at Amathus, the fourth at Jericho, and the fifth at Sepphoris in Galilee." Josephus, Ant. xiv 54:

- ↑ "Josephus uses συνέδριον for the first time in connection with the decree of the Roman governor of Syria, Gabinius (57 BCE), who abolished the constitution and the then existing form of government of Palestine and divided the country into five provinces, at the head of each of which a sanhedrin was placed ("Ant." xiv 5, § 4)." via Jewish Encyclopedia: Sanhedrin:

- ↑ Armstrong 1996, p. 126

- ↑ Sicker 2001, p. 75

- ↑ Dave Winter (1999). Israel Handbook: With the Palestinian Authority Areas. Footprint Handbooks. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-900949-48-4.

- ↑ Emil Schürer; Géza Vermès; Fergus Millar (1973). History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ. A&C Black. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-567-02242-4.

- ↑ "Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews – Book XVIII, "Cyrenius came himself into Judea, which was now added to the province of Syria"". Ccel.org. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, pp. 247–248: "Consequently, the province of Judea may be regarded as a satellite of Syria, though, in view of the measure of independence left to its governor in domestic affairs, it would be wrong to say that in the Julio-Claudian era Judea was legally part of the province of Syria."

- ↑ A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben-Sasson editor, 1976, p. 247: "When Judea was converted into a Roman province [in 6 CE, p. 246], Jerusalem ceased to be the administrative capital of the country. The Romans moved the governmental residence and military headquarters to Caesarea. The centre of government was thus removed from Jerusalem, and the administration became increasingly based on inhabitants of the Hellenistic cities (Sebaste, Caesarea and others)."

- ↑ John P. Meier's A Marginal Jew, vol. 1, ch. 11; also H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, 1976, ISBN 0-674-39731-2, p. 251: "But after the first agitation (which occurred in the wake of the first Roman census) had faded out, we no longer hear of bloodshed in Judea until the days of Pilate."

- ↑ H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, 1976, ISBN 0-674-39731-2, The Crisis Under Gaius Caligula, pp. 254–256: "The reign of Gaius Caligula (37–41) witnessed the first open break between the Jews and the Julio-Claudian empire. Until then—if one accepts Sejanus' heyday and the trouble caused by the census after Archelaus' banishment—there was usually an atmosphere of understanding between the Jews and the empire ... These relations deteriorated seriously during Caligula's reign, and, though after his death the peace was outwardly re-established, considerable bitterness remained on both sides. ... Caligula ordered that a golden statue of himself be set up in the Temple in Jerusalem. ... Only Caligula's death, at the hands of Roman conspirators (41), prevented the outbreak of a Jewish-Roman war that might well have spread to the entire East."

- ↑ Acts 21:26–39

- ↑ See also Flavius Josephus, Jewish Antiquities XX, ix, 1.

- ↑ Eusebius, Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica, III, xxxii.

- ↑ Christopher Mackay. "Ancient Rome a Military and Political History" 2007: 230

- ↑ Schaff's Seven Ecumenical Councils: First Nicaea: Canon VII: "Since custom and ancient tradition have prevailed that the Bishop of Aelia [i.e., Jerusalem] should be honored, let him, saving its due dignity to the Metropolis, have the next place of honor."; "It is very hard to determine just what was the "precedence" granted to the Bishop of Aelia, nor is it clear which is the "metropolis" referred to in the last clause. Most writers, including Hefele, Balsamon, Aristenus and Beveridge consider it to be Cæsarea; while Zonaras thinks Jerusalem to be intended, a view recently adopted and defended by Fuchs; others again suppose it is Antioch that is referred to."

- ↑ Browning, Robert. 1978. The Emperor Julian. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, p. 176. ISBN 0-520-03731-6

- ↑ Horn, Cornelia B.; Robert R. Phenix, Jr. 2008. The Lives of Peter the Iberian, Theodosius of Jerusalem, and the Monk Romanus. Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature, p. lxxxviii. ISBN 978-1-58983-200-8

- ↑ The Emperor Justinian and Jerusalem (527–565)

- ↑ Hussey, J.M. 1961. The Byzantine World. New York, New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, p. 25.

- ↑ Karen Armstrong. 1997. Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths. New York, New York: Ballantine Books, p. 229. ISBN 0-345-39168-3

- ↑ "Translation of Sahih Bukhari, Book 21, Number 281: "Do not set out on a journey except for three Mosques i.e. Al-Masjid-AI-Haram, the Mosque of Allah's Apostle, and the Mosque of Al-Aqsa, (Mosque of Jerusalem)."". Islamicity.com. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ Ostrogorsky, George. 1969. History of the Byzantine State. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, p. 104. ISBN 0-8135-0599-2

- ↑ Leslie J. Hoppe (2000). The Holy City: Jerusalem in the Theology of the Old Testament. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5081-3.

- ↑ Theophilus (of Edessa) (2011). Theophilus of Edessa's Chronicle and the Circulation of Historical Knowledge in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Liverpool University Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-84631-698-2.

- ↑ Elizabeth Jeffreys; Fiona K. Haarer (2006). Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Byzantine Studies: London, 21-26 August, 2006. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7546-5740-8.

- ↑ Miriam Greenblatt (2002). Charlemagne and the Early Middle Ages. Benchmark Books. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7614-1487-2.

- ↑ Heck, Gene W. Charlemagne, Muhammad, and the Arab roots of capitalism. p. 172.

- ↑ Majid Khadduri (2006). War and Peace in the Law of Islam. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-58477-695-6.

- 1 2 Guy le Strange (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems from AD 650 to 1500, Translated from the Works of the Medieval Arab Geographers. Florence: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- ↑ Ross Burns (2005). Damascus: A History. Routledge. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-415-27105-9.

- ↑ Singh, Nagendra. 2002. "International Encyclopedia of Islamic Dynasties"'

- ↑ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund. 2007. "Historic Cities of the Islamic World

- ↑ Runciman, Steven. 1951. A History of the Crusades: Volume 1 The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 279–290. ISBN 0-521-06161-X

- ↑ Adrian J. Boas (2001). Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades: Society, Landscape and Art in the Holy City Under Frankish Rule. London: Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 9780415230001.

- ↑ Larry H. Addington (1990). The Patterns of War Through the Eighteenth Century. Midland book. Indiana University Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780253205513.

... in the Sixth Crusade, Frederick II ...concluded a treaty with the Saracens in 1229 that placed Jerusalem under Christian control but allowed Muslim and Christian alike freedom of access to the religious shrines of the city. ... Within fifteen years of Frederick's departure from the Holy Land, the Khwarisimian Turks, successors to the Seljuks, rampaged through Syria and Palestine, capturing Jerusalem in 1244. (Jerusalem would not be ruled again by Christians until the British occupied it in December 1917, during World War I.)

- ↑ Denys Pringle (2007). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: Volume 3, The City of Jerusalem: A Corpus. The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-521-39038-5.

During the period of Christian control of Jerusalem between 1229 and 1244 ...

- ↑ Annabel Jane Wharton (2006). Selling Jerusalem: Relics, Replicas, Theme Parks. University of Chicago Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-226-89422-5.

(footnote 19): It is perhaps worth noting that the same sultan, al-Malik al-Kamil, was later involved in the negotiations with Emperor Frederick II that briefly reestablished Latin control in Jerusalem between 1229 and 1244.

- ↑ Hossein Askari (2013). Conflicts in the Persian Gulf: Origins and Evolution. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-137-35838-7.

Later, during the years 1099 through 1187 AD and 1229 through 1244 AD, Christian Crusaders occupied Jerusalem ...

- ↑ Moshe Ma'oz, ed. (2009). The Meeting of Civilizations: Muslim, Christian, and Jewish. Sussex Academic Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-84519-395-9.

(Introduction by Moshe Ma'oz) ... When the Christian Crusaders occupied Jerusalem (AD 1099–1187, 1229–1244) ...

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Jerusalem (After 1291)". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ Jerusalem Timeline From David to the 20th century Archived 27 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "10 Facts about the Walls of Jerusalem". eTeacher Hebrew. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ Ambraseys, N. (2009). Earthquakes in the Mediterranean and Middle East: A Multidisciplinary Study of Seismicity up to 1900 (First ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 444–451. ISBN 978-0521872928.

- ↑ Thomas Augustine Prendergast (2004). Chaucer's Dead Body: From Corpse to Corpus. Psychology Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-415-96679-5.

- ↑ Nejla M. Abu Izzeddin (1993). The Druzes: A New Study of Their History, Faith, and Society. BRILL. p. 192. ISBN 90-04-09705-8.

- ↑ Asali, K.J. Jerusalem in History. Brooklyn, New York: Olive Branch Press, p. 215. ISBN 978-1-56656-304-8

- ↑ Salmon, Thomas (1744). Modern History, Or, The Present State of All Nations: Describing Their Respective Situations, Persons, Habits, and Buildings, Manners, Laws and Customs ... Plants, Animals, and Minerals. p. 461.

- ↑ Fisk and King, 'Description of Jerusalem,' in The Christian Magazine, July 1824, p. 220. Mendon Association, 1824.

- ↑ "Batei Mahseh Square". Jerusalem Municipality. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ↑ "Mishkenot Sha'ananim". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ Mishkenot Sha'ananim Archived 10 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hasson, Nir (18 April 2011). "A new state-funded project lets photo albums tell the history of the Land of Israel – Israel News | Haaretz Daily Newspaper". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ Simon Goldhill (2009). Jerusalem: City of Longing. Harvard University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-674-03772-4.

- ↑ Segev, Tom (1999). One Palestine, Complete. Metropolitan Books. pp. 295–313. ISBN 0-8050-4848-0. The group assembled at the Wall shouting "the Wall is ours". They raised the Jewish national flag and sang Hatikvah, the Israeli anthem. The authorities had been notified of the march in advance and provided a heavy police escort in a bid to prevent any incidents. Rumours spread that the youths had attacked local residents and had cursed the name of Muhammad.

- ↑ Levi-Faur, Sheffer and Vogel, 1999, p. 216.

- ↑ Sicker, 2000, p. 80.

- ↑ 'The Wailing Wall In Jerusalem Another Incident', The Times, Monday, 19 August 1929; p. 11; Issue 45285; col D.

- ↑ Prince-Gibson, Eetta (27 July 2006). "Reflective truth". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ↑ Yoav Gelber, Independence Versus Nakba; Kinneret–Zmora-Bitan–Dvir Publishing, 2004, ISBN 965-517-190-6, p.104

- ↑ "Christians in the Holy Land" Edited by Michael Prior and William Taylor. ISBN 0-905035-32-1. p. 104: Albert Aghazarian "The significance of Jerusalem to Christians". This writer states that "Jews did not own any more than 20% of this quarter" prior to 1948

- ↑ "Palestine and Palestinians", p. 117.

- ↑ "Trump Jerusalem move sparks Israeli-Palestinian clashes", BBC News, 7 December 2017

- ↑ "Paraguay becomes third country to open embassy in Jerusalem". Retrieved 2018-05-23.

Bibliography

- Armstrong, Karen (1996). Jerusalem – One City. Three Faiths. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-39168-1.

- Sicker, Martin (2001). Between Rome and Jerusalem: 300 years of Roman-Judaean relations. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-97140-3.

External links

- Main Events in the History of Jerusalem at CenturyOne Bookstore

This article is issued from

Wikipedia.

The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.

-Aerial-Jerusalem-Temple_Mount-Temple_Mount_(south_exposure).jpg)