Acre, Israel

Acre

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | ||

| • ISO 259 | ʕakko | |

| ||

| ||

Acre | ||

| Coordinates: 32°55′40″N 35°04′54″E / 32.92778°N 35.08167°ECoordinates: 32°55′40″N 35°04′54″E / 32.92778°N 35.08167°E | ||

| Grid position | 156/258 PAL | |

| Country |

| |

| District | Northern | |

| Founded |

3000 BCE (Bronze Age settlement) 1550 BCE (Canaanite settlement) 1104 (Crusader rule) 1291 (Mamluk rule) 1948 (Israeli city) | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | City | |

| • Mayor | Shimon Lankri | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 13,533 dunams (13.533 km2 or 5.225 sq mi) | |

| Population (2017)[1] | ||

| • Total | 48,303 | |

| • Density | 3,600/km2 (9,200/sq mi) | |

| UNESCO World Heritage site | ||

| Official name | Old City of Acre | |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, v | |

| Reference | 1042 | |

| Inscription | 2001 (25th Session) | |

| Area | 63.3 ha | |

| Buffer zone | 22.99 ha | |

Acre (/ˈɑːkər/ or /ˈeɪkər/, Hebrew: עַכּוֹ, ʻAko, most commonly spelled as Akko; Arabic: عكّا, ʻAkkā)[2] is a city in the coastal plain region of Israel's Northern District at the extremity of Haifa Bay. The city occupies an important location, as it sits on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, traditionally linking the waterways and commercial activity with the Levant.[3] The important land routes meeting here are the north–south one following the coast and the road cutting inland through the Jezreel Valley; Acre also benefits from one of the very rare natural harbours on the coast of the Land of Israel. This location helped it become one of the oldest cities in the world, continuously inhabited since the Middle Bronze Age, some 4,000 years ago.

Acre is the holiest city of the Bahá'í Faith and receives many Baha'i pilgrims. In 2017, the population was 48,303.[1] Acre is a mixed city that includes Jews, Muslims, Christians, Druze, and Baha'is. The mayor is Shimon Lankri, who was reelected in 2011.[4]

Etymology

The etymology of the name is unknown, but apparently not Semitic.[5] The name is recorded in Egyptian hieroglyphics, in Akkadian (in the Amarna letters), in Assyrian,[5] and once in Biblical Hebrew.[6]

The city was known as Ptolemais during the Hellenistic and Roman-Byzantine periods. During the Crusades it was known as St. Jean d'Acre after the Knights Hospitaller, who had their headquarters there.

According to legend, the Hebrew name Akko is a contraction of the Hebrew phrase "ad koh", meaning "until here" (and no further). In the legend, when the ocean was created, it expanded until it reached Acre, and then stopped expanding.[5]

History

Overview

The first settlement at Acre took place during the Early Bronze Age. The site was abandoned after a few centuries.[7] A large town was established at Acre during the Middle Bronze Age,[7] and was continuously inhabited from then on. It was subject to conquest and destruction several times, most recently in 1291 when the Mamluks razed the city after they had taken it from the Crusaders. In the 14th century and into the 15th century it was no more than a large village. Acre is counted among the oldest continuously inhabited sites in the region.[8]

Bronze Age

The remains of the oldest settlement at the site of modern Acre were found at the tell (archaeological mound), located 1.5 km east of the modern city of Acre, known as Tel Akko in Hebrew and Tell el-Fukhar in Arabic, and date to the Early Bronze Age (c. 3500–3050 BCE),[7] at about 3000 BC.[3] This farming community endured for only a couple of centuries, after which the site was abandoned, possibly after being inundated by rising seawaters.[7]

Acre was resettled as an urban centre during the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000–1550 BCE).[7]

Egyptian sources seem to mention Acre, starting possibly with execration texts from c. 1800 BCE.[9][10] The name Aak, which appears on the tribute lists of Thutmose III (1479–1425 BCE), may be a reference to Acre. The Amarna letters (written between c. 1360–1332 BC) also mention a place named Akka,[11] as do the Execration texts, that pre-date them.[12]

Iron Age

Throughout Israelite rule, Akko was politically and culturally affiliated with Phoenicia.[13]

Around 725 BCE, Akko joined Sidon and Tyre in a revolt against Neo-Assyrian king Shalmaneser V.[13]

Hebrew Bible

According to the Hebrew Bible's Book of Judges, Akko is one of the places from which the Israelites did not manage to drive out the Canaanites (Judges 1:31). It is later described in the territory of the tribe of Asher and according to Josephus, was ruled by one of Solomon's provincial governors.

Greek, Judean and Roman periods

Ancient Greek historians referred to the city as Ake (Ancient Greek: Ἄκη), meaning "cure". According to Greek myth, Heracles found curative herbs here to heal his wounds.[14] Josephus called the city Akre. The name was changed to Antiochia Ptolemais (Ancient Greek: Ἀντιόχεια Πτολεμαΐς) shortly after Alexander the Great's conquest, and then to Ptolemais (Πτολεμαΐς), probably by Ptolemy Soter, after the Wars of the Diadochi led to the partition of the kingdom of Alexander the Great.

Strabo refers to the city as once a rendezvous for the Persians in their expeditions against Egypt. About 165 BC Judas Maccabeus defeated the Seleucids in several battles in Galilee, and drove them into Ptolemais. About 153 BC Alexander Balas, son of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, contesting the Seleucid crown with Demetrius, seized the city, which opened its gates to him. Demetrius offered many bribes to the Maccabees to obtain Jewish support against his rival, including the revenues of Ptolemais for the benefit of the Temple in Jerusalem, but in vain. Jonathan Apphus threw in his lot with Alexander and in 150 BC he was received by him with great honour in Ptolemais. Some years later, however, Tryphon, an officer of the Seleucid Empire, who had grown suspicious of the Maccabees, enticed Jonathan into Ptolemais and there treacherously took him prisoner.

The city was captured by Alexander Jannaeus (ruled c. 103–76 BCE), Cleopatra (r. 69–30 BCE) and Tigranes the Great (r. 95–55 BCE). Here Herod the Great (r. 37–4 BCE) built a gymnasium. Roman authors Latinized the Greek name Ake to Ace. Under Claudius, it became a Roman colony under the name Colonia Claudii Caesaris Ptolemais or simply Colonia Ptolemais.[15]

The Christian Acts of the Apostles reports that Luke the Evangelist, Paul the Apostle and their companions spent a day in Ptolemais with the Christian brethren there (Acts 21:7). A Roman colonia was established at the city, Colonia Claudii Cæsaris. The Romans enlarged the port and the city, that flourished for six centuries even as a Christian center.[16]

Byzantine period

After the permanent division of the Roman Empire in 395, Ptolemais-Akko was administered by the successor state, the Byzantine Empire.

Early Islamic period

Following the defeat of the Byzantine army of Heraclius by the Rashidun army of Khalid ibn al-Walid in the Battle of Yarmouk, and the capitulation of the Christian city of Jerusalem to the Caliph Umar, Acre came under the rule of the Rashidun Caliphate beginning in 638.[8] According to the early Muslim chronicler al-Baladhuri, the actual conquest of Acre was led by Shurahbil ibn Hasana, and it likely surrendered without resistance.[17] The Arab conquest brought a revival to the town of Acre, and it served as the main port of Palestine through the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates that followed, and through Crusader rule into the 13th century.[8]

The first Umayyad caliph, Muawiyah I (r. 661-680), regarded the coastal towns of the Levant as strategically important. Thus, he strengthened Acre's fortifications and settled Persians from other parts of Muslim Syria to inhabit the city. From Acre, which became one of the region's most important dockyards along with Tyre, Mu'awiyah launched an attack against Byzantine-held Cyprus. The Byzantines assaulted the coastal cities in 669, prompting Mu'awiyah to assemble and send shipbuilders and carpenters to Acre. The city would continue to serve as the principal naval base of Jund al-Urdunn ("Military District of Jordan") until the reign of Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik (723-743), who moved the bulk of the shipyards north to Tyre.[17] Nonetheless, Acre remained militarily significant through the early Abbasid period, with Caliph al-Mutawakkil issuing an order to make Acre into a major naval base in 861, equipping the city with battleships and combat troops.[18]

During the 10th century, Acre was still part of Jund al-Urdunn.[19] Local Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi visited Acre during the early Fatimid Caliphate in 985, describing it as a fortified coastal city with a large mosque possessing a substantial olive grove. Fortifications had been previously built by the autonomous Emir Ibn Tulun of Egypt, who annexed the city in the 870s, and provided relative safety for merchant ships arriving at the city's port. When Persian traveller Nasir Khusraw visited Acre in 1047, he noted that the large Jama Masjid was built of marble, located in the centre of the city and just south of it lay the "tomb of the Prophet Salih."[18][20] Khusraw provided a description of the city's size, which roughly translated as having a length of 1.24 kilometres (0.77 miles) and a width of 300 metres (984 feet). This figure indicates that Acre at that time was larger than its current Old City area, most of which was built between the 18th and 19th centuries.[18]

Crusader and Ayyubid period

First Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem (1104-1187)

After roughly four years of siege,[21] Acre finally capitulated to the forces of King Baldwin I of Jerusalem in 1104 following the First Crusade. The Crusaders made the town their chief port in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. On the first Crusade, Fulcher relates his travels with the Crusading armies of King Baldwin, including initially staying over in Acre before the army's advance to Jerusalem. This demonstrates that even from the beginning, Acre was an important link between the Crusaders and their advance into the Levant.[22] Its function was to provide Crusaders with a foothold in the region and access to vibrant trade that made them prosperous, especially giving them access to the Asiatic spice trade.[23] By the 1130s it had a population of around 25,000 and was only matched for size in the Crusader kingdom by the city of Jerusalem. Around 1170 it became the main port of the eastern Mediterranean, and the kingdom of Jerusalem was regarded in the west as enormously wealthy above all because of Acre. According to an English contemporary, it provided more for the Crusader crown than the total revenues of the king of England.[23]

The Andalusian geographer Ibn Jubayr wrote that in 1185 there was still a Muslim community in the city who worshipped in a small mosque.

Ayyubid intermezzo (1187-1191)

Acre, along with Beirut and Sidon, capitulated without a fight to the Ayyubid sultan Saladin in 1187, after his decisive victory at Hattin and the subsequent Muslim capture of Jerusalem.

Second Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem (1191-1291)

.jpg)

Acre remained in Muslim hands until it was unexpectedly besieged by King Guy of Lusignan—reinforced by Pisan naval and ground forces—in August 1189. The siege was unique in the history of the Crusades since the Frankish besiegers were themselves besieged, by Saladin's troops. It was not captured until July 1191 when the forces of the Third Crusade, led by King Richard I of England and King Philip II of France, came to King Guy's aid. Acre then served as the de facto capital of the remnant Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1192. During the siege, German merchants from Lübeck and Bremen had founded a field hospital, which became the nucleus of the chivalric Teutonic Order. Upon the Sixth Crusade, the city was placed under the administration of the Knights Hospitaller military order. Acre continued to prosper as major commercial hub of the eastern Mediterranean, but also underwent turbulent times due to the bitter infighting among the Crusader factions that occasionally resulted in civil wars.[24]

The old part of the city, where the port and fortified city were located, protrudes from the coastline, exposing both sides of the narrow piece of land to the sea. This could maximize its efficiency as a port, and the narrow entrance to this protrusion served as a natural and easy defense to the city. Both the archaeological record and Crusader texts emphasize Acre's strategic importance—a city in which it was crucial to pass through, control, and, as evidenced by the massive walls, protect.

Acre was the final stronghold of the Crusader states when much of the Levantine coastline was conquered by Mamluk forces.

Mamluk period (1291-1517)

Acre, having been isolated and largely abandoned by Europe, was conquered by Mamluk sultan al-Ashraf Khalil in a bloody siege in 1291. In line with Mamluk policy regarding the coastal cities (to prevent their future utilization by Crusader forces), Acre was entirely destroyed, with the exception of a few religious edifices considered sacred by the Muslims, namely the Nabi Salih tomb and the Ayn Bakar spring. The destruction of the city led to popular Arabic sayings in the region enshrining its past glory.[24]

In 1321 the Syrian geographer Abu'l-Fida wrote that Acre was "a beautiful city" but still in ruins following its capture by the Mamluks. Nonetheless, the "spacious" port was still in use and the city was full of artisans.[25] Throughout the Mamluk era (1260-1517), Acre was succeeded by Safed as the principal city of its province.[24]

Ottoman period

Incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517, it appeared in the census of 1596, located in the Nahiya of Acca of the Liwa of Safad. The population was 81 households and 15 bachelors, all Muslim. They paid a fixed tax-rate of 25% on agricultural products, including wheat, barley, cotton, goats, and beehives, water buffaloes, in addition to occasional revenues and market toll, a total of 20,500 Akçe. Half of the revenue went to a Waqf.[26][27] English academic Henry Maundrell in 1697 found it a ruin,[28] save for a khan (caravanserai) built and occupied by French merchants for their use,[29] a mosque and a few poor cottages.[28] The khan was named Khan al-Ilfranj after its French founders.[29]

During Ottoman rule, Acre continued to play an important role in the region via smaller autonomous sheikhdoms.[3] Towards the end of the 18th century Acre revived under the rule of Zahir al-Umar, the Arab ruler of the Galilee, who made the city capital of his autonomous sheikhdom. Zahir rebuilt Acre's fortifications, using materials from the city's medieval ruins. He died outside its walls during an offensive against him by the Ottoman state in 1775.[24] His successor, Jazzar Pasha, further fortified its walls when he virtually moved the capital of the Saida Eyelet ("Province of Sidon") to Acre where he resided.[30] Jazzar's improvements were accomplished through heavy imposts secured for himself all the benefits derived from his improvements. About 1780, Jazzar peremptorily banished the French trading colony, in spite of protests from the French government, and refused to receive a consul. Both Zahir and Jazzar undertook ambitious architectural projects in the city, building several caravanserais, mosques, public baths and other structures. Some of the notable works included the Al-Jazzar Mosque, which was built out of stones from the ancient ruins of Caesarea and Atlit and the Khan al-Umdan, both built on Jazzar's orders.[29]

In 1799 Napoleon, in pursuance of his scheme for raising a Syrian rebellion against Turkish domination, appeared before Acre, but after a siege of two months (March–May) was repulsed by the Turks, aided by Sir Sidney Smith and a force of British sailors. Having lost his siege cannons to Smith, Napoleon attempted to lay siege to the walled city defended by Ottoman troops on 20 March 1799, using only his infantry and small-calibre cannons, a strategy which failed, leading to his retreat two months later on 21 May.

Jazzar was succeeded on his death by his mamluk, Sulayman Pasha al-Adil, under whose milder rule the town advanced in prosperity till his death in 1819. After his death, Haim Farhi, who was his adviser, paid a huge sum in bribes to assure that Abdullah Pasha (son of Ali Pasha, the deputy of Sulayman Pasha), whom he had known from youth, will be appointed as ruler--which didn't stop the new ruler from assassinating Farhi. Abdullah Pasha ruled Acre until 1831, when Ibrahim Pasha besieged and reduced the town and destroyed its buildings. During the Oriental Crisis of 1840 it was bombarded on 4 November 1840 by the allied British, Austrian and French squadrons, and in the following year restored to Turkish rule. It regained some of its former prosperity after linking with the Hejaz Railway by a branch line from Haifa in 1913.[31] It was the capital of the Acre Sanjak in the Beirut Vilayet until British occupation on 23 September 1918 during World War I.[31]

Mandatory Palestine

At the beginning of the Mandate period, in the 1922 census of Palestine, Acre had 6,420 residents: 4,883 of whom were Muslim; 1,344 Christian; 102 Baha'i; 78 Jewish and 13 Druze.[32] The British Mandate government reconstructed Acre, and its economic situation improved. The 1931 census counted 7,897 people in Acre, 6076 Muslims, 1523 Christians, 237 Jews, 51 Baha'i and 10 Druse.[33] In 1945 Acre's population numbered 12,360; 9,890 Muslims, 50 Jews, 2,330 Christians, and 90 classified as "other".[34][35]

Acre's fort was converted into a jail, where members of the Jewish underground were held during their struggle against the British, among them Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Shlomo Ben-Yosef, and Dov Gruner. Gruner and ben-Yosef were executed there. Other Jewish inmates were freed by members of the Irgun, who broke into the jail on 4 May 1947 and succeeded in releasing Jewish underground movement activists. Over 200 Arab inmates also escaped.[36]

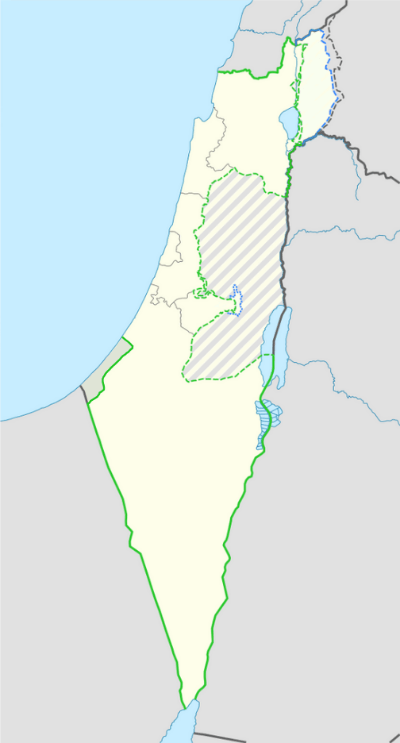

In the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, Acre was designated part of a future Arab state. Before the 1948 Arab-Israeli War broke out, Acre's Arabs attacked neighbouring Jewish settlements and Jewish transportation; in March 1948 42 Jews were killed on an attack on a convoy north of the city,[37] whilst on 18 March four Jewish employees of the electricity company and five British soldiers protecting them were killed whilst travelling to repair damaged lines near the city.[38]

State of Israel

Acre was captured by Israel on 17 May 1948,[39] displacing about three-quarters of the Arab population of the city (13,510 of 17,395).[40] Throughout the 1950s, many Jewish neighbourhoods were established at the northern and eastern parts of the city, as it became a development town, designated to absorb numerous Jewish immigrants, largely Jews from Morocco. The old city of Akko remained largely Arab Muslim (including several Bedouin families), with an Arab Christian neighbourhood in close proximity. The city also attracted Bahá'í worshippers, some of whom became permanent residents in the city, where the Bahá'í Mansion of Bahjí is located. Acre has also served as a base for important events in Baha'i history, including being the birthplace of Shoghi Effendi, and the short-lived schism between Baha'is initiated by the attacks by Mírzá Muhammad `Alí against `Abdu'l-Bahá.[41] Baha'is have since commemorated various events that have occurred in the city, including the imprisonment of Bahá'u'lláh.[42]

In the 1990s, the city absorbed thousands of Jews, who immigrated from the Soviet Union, and later from Russia and Ukraine. Within several years, however, the population balance between Jews and Arabs shifted backwards, as northern neighbourhoods were abandoned by many of its Jewish residents in favour of new housing projects in nearby Nahariya, while many Muslim Arabs moved in (largely coming from nearby Arab villages). Nevertheless, the city still has a clear Jewish majority; in 2011, the population of 46,000 included 30,000 Jews and 14,000 Arabs.[43]

Ethnic tensions erupted in the city on 8 October 2008 after an Arab citizen drove through a predominantly Jewish neighbourhood during Yom Kippur, leading to five days of violence between Arabs and Jews.[44][45][46]

In 2009, the population of Acre reached 46,300.[47] The mayor as of February 2018, Shimon Lankri, was re-elected in 2011.[4]

Demography

Today there are roughly 40,000 people who live in Acre. Among Israeli cities, Acre has a relatively high proportion of non-Jewish residents. Approximately a quarter of its residents are members of other faiths: Christians, Muslims, Druze, and Baha'is. Acre's population is mixed with Jews and Arabs.[48]

According to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, in 2000, 95% of the residents in the Old City were Arab.[49] Only about 15% percent of the current Arab population in the city descends from families who lived there before 1948.[50] In 1999, there were 22 schools in Acre with an enrollment of 15,000 children.[51]

Transportation

The Acre central bus station, served by Egged and Nateev Express, offers intra-city and inter-city bus routes to destinations all over Israel. Nateev Express is currently contracted to provide the intra-city bus routes within Acre. The city is also served by the Acre Railway Station,[52] which is on the main Coastal railway line to Nahariya, with southerly trains to Beersheba and Modi'in-Maccabim-Re'ut.

Education and culture

The Sir Charles Clore Jewish-Arab Community Centre in the Kiryat Wolfson neighbourhood runs youth clubs and programs for Jewish and Arab children. In 1990, Mohammed Faheli, an Arab resident of Acre, founded the Acre Jewish-Arab association, which originally operated out of two bomb shelters. In 1993, Dame Vivien Duffield of the Clore Foundation donated funds for a new building. Among the programs offered is Peace Child Israel, which employs theatre and the arts to teach coexistence. The participants, Jews and Arabs, spend two months studying conflict resolution and then work together to produce an original theatrical performance that addresses the issues they have explored. Another program is Patriots of Acre, a community responsibility and youth tourism program that teaches children to become ambassadors for their city. In the summer, the centre runs an Arab-Jewish summer camp for 120 disadvantaged children aged 5–11. Some 1,000 children take part in the Acre Centre's youth club and youth programming every week. Adult education programs have been developed for Arab women interested in completing their high school education and acquiring computer skills to prepare for joining the workforce. The centre also offers parenting courses, and music and dance classes.[53]

The Acco Festival of Alternative Israeli Theatre is an annual event that takes place in October, coinciding with the holiday of Sukkot.[54] The festival, inaugurated in 1979, provides a forum for non-conventional theatre, attracting local and overseas theatre companies.[55] Theatre performances by Jewish and Arab producers are staged at indoor and outdoor venues around the city.[56]

Sports

The city's football team, Hapoel Acre F.C., is a member of the Israeli Premier League, the top tier of Israeli football. They play in the Acre Municipal Stadium which was opened in September 2011. At the end of the 2008–2009 season, the club finished in the top five, and was promoted to the top tier for a second time, after an absence of 31 years.

In the past the city was also home to Maccabi Acre. however, the club was relocated to nearby Kiryat Ata and was renamed Maccabi Ironi Kiryat Ata.

Other current active clubs are Ahi Acre and the newly formed Maccabi Ironi Acre, both playing in Liga Bet. Both club also host their matches in the Acre Municipal Stadium.

Landmarks

Acre's Old City has been designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. Since the 1990s, large-scale archaeological excavations have been undertaken and efforts are being made to preserve ancient sites. In 2009, renovations were planned for Khan al-Umdan, the "Inn of the Columns," the largest of several Ottoman inns still standing in Acre. It was built near the port at the end of the 18th century by Jazzar Pasha. Merchants who arrived at the port would unload their wares on the first floor and sleep in lodgings on the second floor. In 1906, a clock tower was added over the main entrance marking the 25th anniversary of the reign of the Turkish sultan, Abdul Hamid II.[57]

City walls

In 1750, Zahir al-Umar, the ruler of Acre, utilized the remnants of the Crusader walls as a foundation for his walls. Two gates were set in the wall, the "land gate" in the eastern wall, and the "sea gate" in the southern wall. The walls were reinforced between 1775 and 1799 by Jazzar Pasha and survived Napoleon's siege. The wall was thin: its height was between 10 metres (33 ft) and 13 metres (43 ft) and its thickness only 1.5 metres (4.9 ft).[58]

A heavy land defensive wall was built north and east to the city in 1800–1814 by Jazzar Pasha and his Jewish advisor, Haim Farhi. It consists of a modern counter artillery fortification which includes a thick defensive wall, a dry moat, cannon outposts and three burges (large defensive towers). Since then, no major modifications have taken place. The sea wall, which remains mostly complete, is the original wall built by Zahir that was reinforced by Jazzar Pasha. In 1910, two additional gates were set in the walls, one in the northern wall and one in the north-western corner of the city. In 1912, the Acre lighthouse was built on the south-western corner of the walls.

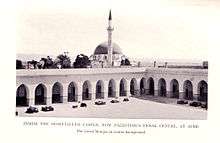

Al-Jazzar Mosque

Al-Jazzar Mosque was built in 1781. Jazzar Pasha and his successor, Sulayman Pasha al-Adil, are both buried in a small graveyard adjacent to the mosque. In a shrine on the second level of the mosque, a single hair from Muhammad's beard is kept and shown on special ceremonial occasions.

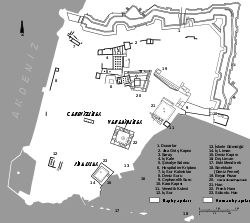

Citadel of Acre

The current building which constitutes the citadel of Acre is an Ottoman fortification, built on the foundation of the citadel of the Knights Hospitaller. The citadel was part of the city's defensive formation, reinforcing the northern wall. During the 20th century the citadel was used mainly as Acre Prison and as the site for a gallows. During the British mandate period, activists of Jewish Zionist resistance movements were held prisoner there; some were executed there.

Hamam al-Basha

Built in 1795 by Jazzar Pasha, Acre's Turkish bath has a series of hot rooms and a hexagonal steam room with a marble fountain. It was used by the Irgun as a bridge to break into the citadel's prison. The bathhouse kept functioning until 1950.

Hospitaller refectory

Under the citadel and prison of Acre, archaeological excavations revealed a complex of halls, which was built and used by the Knights Hospitaller.[59] This complex was a part of the Hospitallers' citadel, which was included in the northern defences of Acre. The complex includes six semi-joined halls, one recently excavated large hall, a dungeon, a refectory (dining room) and remains of a Gothic church.

Other medieval sites

Other medieval European remains include the Church of Saint George and adjacent houses at the Genovese Square (called Kikar ha-Genovezim or Kikar Genoa in Hebrew). There were also residential quarters and marketplaces run by merchants from Pisa and Amalfi in Crusader and medieval Acre.

Bahá'í holy places

There are many Bahá'í holy places in and around Acre. They originate from Bahá'u'lláh's imprisonment in the Citadel during Ottoman Rule. The final years of Bahá'u'lláh's life were spent in the Mansion of Bahjí, just outside Acre, even though he was still formally a prisoner of the Ottoman Empire. Bahá'u'lláh died on 29 May 1892 in Bahjí, and the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh is the most holy place for Bahá'ís — their Qiblih, the location they face when saying their daily prayers. It contains the remains of Bahá'u'lláh and is near the spot where he died in the Mansion of Bahjí. Other Bahá'í sites in Acre are the House of `Abbúd (where Bahá'u'lláh and his family resided) and the House of `Abdu'lláh Páshá (where later 'Abdu'l-Bahá resided with his family), and the Garden of Ridván where he spent the end of his life. In 2008, the Bahai holy places in Acre and Haifa were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List.[60][61]

Archaeology

Excavations at Tell Akko began in 1973.[62] In 2012, archaeologists excavating at the foot of the city's southern seawall found a quay and other evidence of a 2,300-year old port. Mooring stones weighing 250-300 kilograms each were unearthed at the edge of a 5-meter long stone platform chiseled in Phoenician-style, thought to be an installation that helped raise military vessels from the water onto the shore.[63]

Crusades

Under the citadel and prison of Acre, archaeological excavations revealed a complex of halls, which was built and used by the Hospitallers Knights.[59] This complex was a part of the Hospitallers' citadel, which was combined in the northern wall of Acre. The complex includes six semi-joined halls, one recently excavated large hall, a dungeon, a dining room and remains of an ancient Gothic church. Medieval European remains include the Church of Saint George and adjacent houses at the Genovese Square (called Kikar ha-Genovezim or Kikar Genoa in Hebrew). There were also residential quarters and marketplaces run by merchants from Pisa and Amalfi in Crusader and medieval Acre.

International relations

Acre is twinned with:

|

|

Notable people associated with Acre

Apart from those mentioned in the article (Alexander the Great, St Paul, Richard the Lionheart, Napoleon):

- Francis of Assisi (1181/1182 – October 3, 1226) came on pilgrimage to the Holy Land passing through Acre

- Nahmanides (1194–1270), Jewish scholar and Talmud expert

- Heinrich Walpot (died before 1208), first Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights

- Otto von Kerpen (died 1209), second Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights

- Marco Polo (1254–1324) sailed from Venice to Acre in 1271

- Joan of Acre (1272–1307), English princess born in Acre

- General Caffarelli (1759 – 1799), French general and scholar; died and buried in Acre

- Ghassan Kanafani (born 1936, died 1972), Palestinian writer.

- Ella German (born 1937), girlfriend of Lee Harvey Oswald, moved to Akko sometime between 1993 and 2013

- Raymonda Tawil (born 1940), Palestinian journalist and activist

- Lydia Hatuel-Czuckermann (born 1963), Olympic foil fencer

- Ayelet Ohayon (born 1974), Olympic foil fencer

- Delila Hatuel (born 1980), Olympic foil fencer

- Avigail Alfatov (born 1996), national fencing champion, soldier, and Miss Israel 2014

In popular culture

Acre appears in the video game Assassin's Creed.

See also

References

- 1 2 "List of localities, in Alphabetical order" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ↑ Other spellings and historical names of the city include Accho, Acco and (Bahá'í orthography) Akká, or formerly Aak, Ake, Akre, Akke, Ocina, Antiochia Ptolemais (Greek: Ἀντιόχεια τῆς Πτολεμαΐδος), Antiochenes, Ptolemais Antiochenes, Ptolemais or Ptolemaïs, Colonia Claudii Cæsaris, and St.-Jean d'Acre (Acre for short)

- 1 2 3 "Old City of Acre.", UNESCO World Heritage Center. World Heritage Convention. Web. 15 Apr 2013

- 1 2 "Head to Head / Acre Mayor Shimon Lankri, is there a desire to 'Judaize' Israel's mixed towns?". Haaretz.com. 27 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 Acre: Historical overview (Hebrew)

- ↑ Judges 1:31

- 1 2 3 4 5 Avraham Negev and Shimon Gibson (2001). Akko (Tel). Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. New York and London: Continuum. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8264-1316-1.

- 1 2 3 Petersen, 2001, p. 68

- ↑ Jerome Murphy-O'Connor (2008). The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700. Oxford Archaeological Guides. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-19-923666-4. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce, The Routledge Handbook of The Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia, Routledge, 2009, p. 19

- ↑ Burraburias II to Amenophis IV, letter No. 2

- ↑ Aharoni, Yohanan (1979). The land of the Bible: a historical geography. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 144–147. ISBN 978-0-664-24266-4. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- 1 2 Becking, Bob (1992): The Fall of Samaria: An Historical and Archaeological Study, Brill, ISBN 90-04-09633-7, pp. 31–35

- ↑ The Guide to Israel, Zev Vilnay, Ahiever, Jerusalem, 1972, p. 396

- ↑

- ↑ Hazlit, W. (1851) The Classical Gazetteer Archived 2006-08-22 at the Wayback Machine. p.4

- 1 2 Sharon, 1997, p. 23

- 1 2 3 Sharon, 1997, p. 24

- ↑ le Strange, 1890, p. 30

- ↑ le Strange, 1890, pp. 328-329.

- ↑ Sharon, 1997, p. 25

- ↑ Peters, Edward. The First Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source Materials. The Middle Ages Series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1971. (23-90, 104-105, 122-124, 149-151)

- 1 2 Jonathan Riley-Smith, University of Cambridge. "A History of the World – Object : Hedwig glass beaker". BBC. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Šārôn, Moše (1997). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae (CIAP).: A. Volume one. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10833-2. , page 26

- ↑ le Strange, 1890, p. 333

- ↑ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 192

- ↑ Note that Rhode, 1979, p. 6 writes that the Safad register that Hütteroth and Abdulfattah studied was not from 1595/6, but from 1548/9.

- 1 2 Maundrell, 1703, pp. 53-55

- 1 2 3 Sharon, 1997, p. 28

- ↑ Sharon, 1997, p. 27

- 1 2 Kürekli, Recep (Nevşehir University). "Socio-Economic Transformation by the Extension of Hedjaz Railway to the Mediterranean Sea: A Case Study on Haifa Qadâ" (PDF). History Studies - International Journal of History, Middle East Special Issue 2010 (in Turkish). doi:10.9737/hist_146 (inactive 2018-10-01). Retrieved 2018-07-07.

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Acre, p. 36

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 99

- ↑ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 4

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 40

- ↑ "Acre Jail Break". Britain's Small Wars. Archived from the original on 2008-07-27. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ↑ "Arab Attacks On Jewish Convoys", The Times, 29 March 1948, p4, issue 51031

- ↑ "British Casualties In Palestine" The Times, 19 March 1948, p4, issue 51024

- ↑ Operation Ben-Ami

- ↑ Karsh (2010), p. 268

- ↑ Warburg, Margit (2006). Citizens of the World: A History and Sociology of the Bahaʹis from a Globalisation Perspective. p. 424.

- ↑ Priestley, Gerda (2008). Cultural Resources for Tourism: Patterns, Processes and Policies. p. 32.

- ↑ "Locality File". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 2011. Archived from the original (XLS) on 2013-09-23.

- ↑ Khoury, Jack (October 13, 2008). "Peres in Acre: In Israel There Are Many Religions, But Only One Law". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Kershner, Isabel (October 12, 2008). "Israeli City Divided by Sectarian Violence". New York Times. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Izenberg, Dan (October 12, 2008). "Police Arrest Acre Yom Kippur driver". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ "Table 3 – Population of Localities Numbering Above 2,000 Residents and Other Rural Population" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. December 31, 2009. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Acre (Akko)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- ↑ http://www.cbs.gov.il/www/statistical/arabju.pdf

- ↑ Stern, Yoav. "For Love of Acre". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Hertz-Lazarowitz, Rachel (1999). "Cooperative Learning in Israel's Jewish and Arab Schools: A Community Approach". Theory into Practice. 38 (2): 105–113. JSTOR 1477231.

- ↑ "Israel Railways – Akko". Israel Railways. Israel Railways. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- ↑ "Ambassadors for peace emerging from mixed Israeli neighborhood". ISRAEL21c.

- ↑ "Curtain rises over Acre's abundantly diverse Fringe Theater Festival". Haaretz.com. 11 October 2011.

- ↑ "Acre Fringe Theatre Festival". akko.org.il.

- ↑ "Four-day Acre Festival opens Sunday". ynet.

- ↑ "Unearthing Acre's Ottoman roots". Haaretz.com. 4 February 2009.

- ↑ Kahanov, 2014, p.147.

- 1 2 "Archaeology in Israel – Acco (Acre)". Jewishmag.com. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Baha'i Shrines Chosen as World Heritage sites". Baha'i World News Service. July 8, 2008. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Glass, Hannah (July 10, 2008). "Israeli Baha'i Sites Recognized by UNESCO". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Moshe Dothan, Akko: Interim Excavation Report First Season, 1973/4, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 224, pp. 1-48, (Dec., 1976)

- ↑ "2,000-year old port discovered in Acre". Haaretz.com. 18 July 2012.

- ↑ "Bielsko-Biała – Partner Cities". © 2008 Urzędu Miejskiego w Bielsku-Białej. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- ↑ "La Rochelle: Twin towns". www.ville-larochelle.fr. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Pisa – Official Sister Cities". Comune di Pisa. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-920405-41-4.

- Kahanov, Yaacov; Stern, Eliezer; Cvikel, Deborah; Me-Bar, Yoav (2014). "Between Shoal and Wall: The naval bombardment of Akko, 1840". The Mariner's Mirror. 100 (2): 147–167. doi:10.1080/00253359.2014.901699.

- Karsh, E. (2010). Palestine Betrayed. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12727-0.

- Maundrell, H. (1703). A Journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem: At Easter, A. D. 1697. Oxford: Printed at the Theatre.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Pappé, I. (2006). The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. London and New York: Oneworld. ISBN 978-1-85168-467-0.

- Peters, E. (1971). The First Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source Materials. The Middle Ages Series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. (23-90, 104-105, 122-124, 149-151)

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Philipp, Thomas (2001). Acre -The rise and fall of a Palestinian city, 1730-1831. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12326-6.

- Pococke, R. (1745). A description of the East, and some other countries. 2. London: Printed for the author, by W. Bowyer.

- Pringle, Denys (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetter. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521 46010 7. (pp. 16-17)

- Rhode, H. (1979). Administration and Population of the Sancak of Safed in the Sixteenth Century. Columbia University.

- Riley-Smith, J. (2010), A History of the World-Object: Hedwig glass beaker, BBC

- Sharon, M. (1997). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, A. 1. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10833-2.

- Strange, le, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Torstrick, Rebecca L. (2000). The Limits of Coexistence: Identity Politics in Israel. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11124-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Acre, Israel. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Akko. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Acre (town). |

- Acre Municipality official website

- Official website of the Old City of Acre

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 3: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Orit Soffer and Yotam Carmel,Hamam al-Pasha: The implementation of urgent ("first aid") conservation and restoration measures, Israel Antiquities Site – Conservation Department

.svg.png)