Solomon's Temple

| Solomon's Temple | |

|---|---|

| בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ | |

Artistic depiction of the First Temple in Jerusalem | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Ancient Jerusalem |

| Deity | Yahweh |

| Architectural description | |

| Creator | Solomon |

| Destroyed | 587 BC |

According to the Hebrew Bible, Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple, was the Holy Temple (Hebrew: בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ: Beit HaMikdash) in ancient Jerusalem before its destruction by Nebuchadnezzar II after the Siege of Jerusalem of 587 BCE and its subsequent replacement with the Second Temple in the 6th century BCE.

The Hebrew Bible states that the temple was constructed under Solomon, king of the United Kingdom of Israel and Judah and that during the Kingdom of Judah, the temple was dedicated to Yahweh, and is said to have housed the Ark of the Covenant. Jewish historian Josephus says that "the temple was burnt four hundred and seventy years, six months, and ten days after it was built".[1]

Because of the religious sensitivities involved, and the politically volatile situation in Jerusalem, only limited archaeological surveys of the Temple Mount have been conducted. No archaeological excavations have been allowed on the Temple Mount during modern times. Therefore, there are very few pieces of archaeological evidence for the existence of Solomon's Temple.[2] An Ivory pomegranate which mentions priests in the house "of ---h", and an inscription recording the Temple's restoration under Jehoash have both appeared on the antiquities market, but their authenticity has been challenged and they are the subject of controversy.

In the Tanakh

The only source of information on the First Temple is the Tanakh.[3] According to the biblical sources, the temple was constructed under Solomon, during the united monarchy of Israel and Judah. The Bible describes Hiram I of Tyre who furnished architects, workmen and cedar timbers for the temple of his ally Solomon at Jerusalem. He also co-operated with Solomon in mounting an expedition on the Red Sea. 1 Kings 6:1 puts the date of the beginning of building the temple "in the fourth year of Solomon's reign over Israel". The conventional dates of Solomon's reign are circa 970 to 931 BCE. This puts the date of its construction in the mid-10th century BCE.[4] Schmid and Rupprecht are of the view that the site of the temple used to be a Jebusite shrine which Solomon chose in an attempt to unify the Jebusites and Israelites.[5] 1 Kings 9:10 says that it took Solomon 20 years altogether to build the Temple and his royal palace. The Temple itself finished being built after 7 years.[6] During the united monarchy the Temple was dedicated to Yahweh, the God of Israel, and housed the Ark of the Covenant.[7] Rabbinic sources[8] state that the First Temple stood for 410 years and, based on the 2nd-century work Seder Olam Rabbah, place construction in 832 BCE and destruction in 422 BCE (3338 AM), 165 years later than secular estimates.[9]

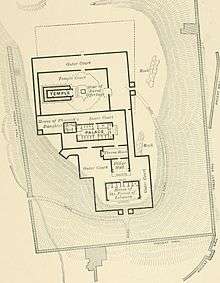

The exact location of the Temple is unknown: it is believed to have been situated upon the hill which forms the site of the 1st century Second Temple and present-day Temple Mount, where the Dome of the Rock is situated.

According to the Tanakh, the Temple was plundered by the Neo-Babylonian Empire king Nebuchadnezzar II when the Babylonians attacked Jerusalem during the brief reign of Jehoiachin c. 598 BCE (2 Kings 24:13). A decade later, Nebuchadnezzar again besieged Jerusalem and after 30 months finally breached the city walls in 587 BCE, subsequently burning the Temple, along with most of the city (2 Kings 25). According to Jewish tradition, the Temple was destroyed on Tisha B'Av, the 9th day of Av (Hebrew calendar).[10]

Architectural description

The Temple of Solomon is considered to be built according to Phoenician design, and its description is considered the best description of what a Phoenician temple looked like.[11] The detailed descriptions provided in the Tanakh are the sources for reconstructions of its appearance. Technical details are lacking, since the scribes who wrote the books were not architects or engineers.[12] Nevertheless, the descriptions have inspired modern replicas of the temple and influenced later structures around the world.

Reconstructions differ; the following is largely based on Easton's Bible Dictionary and the Jewish Encyclopedia:

Holy of Holies

The Holy of Holies, or Kodesh haKodashim in Hebrew, (1 Kings 6:19; 8:6), also called the "Inner House" (6:27), (Heb. 9:3) was 20 cubits in length, breadth, and height. The usual explanation for the discrepancy between its height and the 30-cubit height of the temple is that its floor was elevated, like the cella of other ancient temples.[12] It was floored and wainscotted with cedar of Lebanon (1 Kings 6:16), and its walls and floor were overlaid with gold (6:20, 21, 30) amounting to 600 talents (2 Chr. 3:8) or roughly 20 metric tons. It contained two cherubim of olive-wood, each 10 cubits high (1 Kings 6:16, 20, 21, 23–28) and each having outspread wings of 10 cubits span, so that, since they stood side by side, the wings touched the wall on either side and met in the center of the room. There was a two-leaved door between it and the Holy Place overlaid with gold (2 Chr. 4:22); also a veil of tekhelet (blue), purple, and crimson and fine linen (2 Chronicles 3:14; compare Exodus 26:33). It had no windows (1 Kings 8:12) and was considered the dwelling-place of the "name" of God.

The Kodesh haKodashim (the Holy of Holies) was prepared to receive and house the Ark (1 Kings 6:19); and when the Temple was dedicated, the Ark, containing the original tablets of the Ten Commandments, was placed beneath the cherubim (1 Kings 8:6).

Hekhal

The Hekhal, or Holy Place, (1 Kings 8:8–10), is also called the "greater house" (2 Chr. 3:5) and the "temple" (1 Kings 6:17); the word also means "palace",[12] was of the same width and height as the Holy of Holies, but 40 cubits in length. Its walls were lined with cedar, on which were carved figures of cherubim, palm-trees, and open flowers, which were overlaid with gold. Chains of gold further marked it off from the Holy of Holies. The floor of the Temple was of fir-wood overlaid with gold. The door-posts, of olive-wood, supported folding-doors of fir. The doors of the Holy of Holies were of olive-wood. On both sets of doors were carved cherubim, palm-trees, and flowers, all being overlaid with gold (1 Kings 6:15 et seq.)

Etymology

The noun hekhal (Hebrew: היכל, borrowed from Sumerian 𒂍𒃲 (É.GAL) "big house") means "a large building". This can be either the main building of the Temple in Jerusalem (that is the nave, or sanctuary, of the Temple), or a palace such as the "palace" of Ahab, king of Samaria, or the "palace" of the King of Babylon.

Hekhal is used 80 times in the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible. Of these, 70 refer to the House of the LORD (in Hebrew Bible בֵּית יְהוָה beit Yahweh), the other 10 are references to palaces. There is no reference to any part of the tabernacle using this term in the Hebrew Bible.

In the year that king Uzziah died. I saw the LORD sitting upon a throne high and lifted up, and His train filled the hekhal (sanctuary).

Use in architecture

In older English versions of the Bible, including the King James Version, the term temple is used to translate hekhal. In modern versions more reflective of archaeological research, the distinction is made of different sections of the whole Temple. Scholars and archaeologists generally agree on the structure of Solomon's Temple as described in 1 Kings 6:3–5, with the main building, the hekhal, in English now sometimes called "the sanctuary", the devir, the inner sanctuary, and finally the Holy of Holies.[13]

This main building was between the outer altar, where most sacrifices were performed, and inside at the far end was the entry to the Holy of Holies, originally containing the Ark of the Covenant. The main hekhal contained a number of sacred ritual objects including the seven branched candlestick, the inner altar for incense offerings (also called the "Golden Altar"), and the table of the showbread.

The same architectural layout of the temple was adopted in synagogues leading to the hekhal being applied in Sephardi usage to the Ashkenazi Torah ark, the equivalent of the nave.[14]

Porch

The Ulam, or porch, acted as an entrance before the Temple on the east (1 Kings 6:3; 2 Chr. 3:4; 9:7). This was 20 cubits long (corresponding to the width of the Temple) and 10 cubits deep (1 Kings 6:3). (ESV 2 Chr. 3:4) notes that this porch was 120 cubits high. The description does not specify whether a wall separated it from the next chamber. In the porch stood the two pillars Jachin and Boaz (1 Kings 7:21; 2 Kings 11:14; 23:3), which were 18 cubits in height.

Chambers

Chambers were built around the Temple on the southern, western and northern sides (1 Kings 6:5–10). These formed a part of the building and were used for storage. They were probably one story high at first; two more may have been added later.[12]

Courts

According to the Bible, two courts surrounded the Temple. The Inner Court (1 Kings 6:36), or Court of the Priests (2 Chr. 4:9), was separated from the space beyond by a wall of three courses of hewn stone, surmounted by cedar beams (1 Kings 6:36). It contained the Altar of burnt-offering (2 Chr. 15:8), the Brazen Sea laver (4:2–5, 10) and ten other lavers (1 Kings 7:38, 39). A brazen altar stood before the Temple (2 Kings 16:14), its dimensions 20 cubits square and 10 cubits high (2 Chr. 4:1). The Great Court surrounded the whole Temple (2 Chr. 4:9). It was here that people assembled to worship. (Jeremiah 19:14; 26:2).

Molten Sea

According to the Hebrew Bible, the Molten Sea or Brazen Sea (ים מוצק "cast metal sea") was a large basin in the Temple for ablution of the priests. It is described in 1 Kings 7:23-26 and 2 Chronicles 4:2-5. It stood in the south-eastern corner of the inner court. According to the Bible it was five cubits high, ten cubits in diameter from brim to brim, and thirty cubits in circumference. The brim was "like the calyx of a lily" and turned outward "about an hand breadth"; or about four inches. It was placed on the backs of twelve oxen, standing with their faces outward. The Book of Kings states that it contains 2,000 baths (90 cubic meters), while Chronicles (2 Chr. 4:5–6) states it can hold up to 3,000 baths (136 cubic meters) and states that its purpose was to afford opportunity for the purification by immersion of the bodies of the priests.

The fact that it was a wash basin which was too large to enter from above lends to the idea that water would likely have flowed from it down into a subcontainer beneath. The water was originally supplied by the Gibeonites, but was afterwards brought by a conduit from Solomon's Pools. The molten sea was made of brass or bronze, which Solomon had taken from the captured cities of Hadarezer, the king of Zobah (1 Chronicles 18:8). Ahaz later removed this laver from the oxen, and placed it on a stone pavement (2 Kings 16:17). It was destroyed by the Chaldeans (2 Kings 25:13).

The lavers, each of which held "forty baths" (1 Kings 7:38), rested on portable holders made of bronze, provided with wheels, and ornamented with figures of lions, cherubim, and palm-trees. The author of the books of the Kings describes their minute details with great interest (1 Kings 7:27–37). Josephus reported that the vessels in the Temple were composed of orichalcum in Antiquities of the Jews. According to 1 Kings 7:48 there stood before the Holy of Holies a golden Altar of Incense and a table for showbread. This table was of gold, as were also the five candlesticks on each side of it. The implements for the care of the candles–tongs, basins, snuffers, and fire-pans–were of gold; and so were the hinges of the doors.

Dedication

1 Kings 8:10-66 and 2 Chronicles 6:1-42 recount the events of the temple's dedication. When the priests emerged from the holy of holies after placing the Ark there, the Temple was filled with an overpowering cloud which interrupted the dedication ceremony,[15] "for the glory of the Lord had filled the house of the Lord" (1 Kings 8:10–11; 2 Chronicles 5:13, 14). Solomon interpreted the cloud as "[proof] that his pious work was accepted":[15]

- The Lord has said that he would dwell in thick darkness.

- I have built you an exalted house, a place for you to dwell in forever. (1 Kings 8:12-13)

The allusion is to Leviticus 16:2:

- The Lord said to Moses:

- Tell your brother Aaron not to come just at any time into the sanctuary inside the curtain before the mercy seat that is upon the ark, or he will die; for I appear in the cloud upon the mercy seat.

Solomon then led the whole assembly of Israel in prayer, noting that the construction on the temple represented a fulfilment of God's promise to David, dedicating the temple as a place of prayer and reconciliation for the people of Israel and for foreigners living in Israel, and highlighting the paradox that God who lives in the heavens cannot really be contained within a single building. The dedication was concluded with sacrifices said to have included "twenty-two thousand bulls and one hundred and twenty thousand sheep".[16]

Archaeology

Because of the religious and political sensitivities involved, no archaeological excavations and only limited surface surveys of the Temple Mount have been conducted since Charles Warren's expedition of 1867–70.[17][18][19] There is no archaeological evidence for the existence of Solomon's Temple, and the building is not mentioned in surviving extra-biblical accounts.[20] Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman argue that the first Jewish temple in Jerusalem was not built until the end of the 7th century BCE, around three hundred years after Solomon.[20] They believe the temple should not really be assigned to Solomon, who they see as little more than a small-time hill country chieftain, and argue that it was most likely built by Josiah, who governed Judah from 639 to 609 BCE.[20]

- An ostracon (excavated prior to 1981), sometimes referred to as the House of Yahweh ostracon, was discovered at Tel Arad, dated to 6th century BCE which mentions a temple which is probably the Temple in Jerusalem.[21]

- A thumb-sized ivory pomegranate (which came to light in 1979) measuring 44 millimetres (1.7 in) in height, and bearing an ancient Hebrew inscription "Sacred donation for the priests in the House of ---h,]", was believed to have adorned a sceptre used by the high priest in Solomon's Temple. It was considered the most important item of biblical antiquities in the Israel Museum's collection.[22] However, in 2004, the Israel Antiquities Authority reported the inscription to be a forgery, though the ivory pomegranate itself was dated to the 14th or 13th century BCE.[23] This was based on the report's claim that three incised letters in the inscription stopped short of an ancient break, as they would have if carved after the ancient break was made. Since then, it has been proven that one of the letters was indeed carved prior to the ancient break, and the status of the other two letters are in question. Some paleographers and others have continued to insist that the inscription is ancient, some dispute this so the authenticity of this writing is still the object of discussion.[24]

- Another artifact, the Jehoash Inscription, which first came to notice in 2003, contains a 15-line description of King Jehoash's ninth-century BCE restoration of the Temple. Its authenticity was called into question by a report by the Israel Antiquities Authority, which said that the surface patina contained microfossils of foraminifera. As these fossils do not dissolve in water, they cannot occur in a calcium carbonate patina, leading initial investigators to conclude that the patina must be an artificial chemical mix applied to the stone by forgers. As of late 2012, the academic community is split on whether the tablet is authentic or not. Commenting on a 2012 report by geologists arguing for the authenticity of the inscription, in October 2012, Hershel Shanks (who believes the inscription is genuine) wrote the current situation was that most Hebrew language scholars believe that the inscription is a forgery and geologists that it is genuine, and thus "Because we rely on experts, and because there is an apparently irresolvable conflict of experts in this case, BAR has taken no position with respect to the authenticity of the Jehoash Inscription."[25]

- By 2006, the Temple Mount Sifting Project had recovered numerous artifacts dating from the 8th to 7th centuries BCE from soil removed in 1999 by the Islamic Religious Trust (Waqf) from the Solomon's Stables area of the Temple Mount. These include stone weights for weighing silver and a First Temple period bulla, or seal impression, containing ancient Hebrew writing which includes the name Netanyahu ben Yaush. Netanyahu is a name mentioned several times in the Book of Jeremiah while the name Yaush appears in the Lachish letters. However, the combination of names was unknown to scholars.[26][27]

- In 2007, artifacts dating to the 8th to 6th centuries BCE were described as being possibly the first physical evidence of human activity at the Temple Mount during the First Temple period. The findings included animal bones; ceramic bowl rims, bases, and body sherds; the base of a juglet used to pour oil; the handle of a small juglet; and the rim of a storage jar.[28][29]

Other contemporary temples

There is archaeological and written evidence of three Israelite temples, either contemporary or of very close date, dedicated to Yahweh (Elephantine temple, probably Arad too), either in the Land of Israel or in Egypt. Two of them have the same general outline as given by the Bible for the Jerusalem Temple.

- The Israelite temple at Tel Arad in Judah, 10th to 8th/7th century BCE[30] and possibly dedicated to Yahweh and Asherah.[31]

- The Jewish temple at Elephantine in Egypt, already standing in 525 BCE[32]

- The Israelite temple at Tel Motza, c. 750 BCE discovered in 2012 a few kilometres west of Jerusalem.

- Several Iron Age temples have been found in the region that have striking similarities to the Temple of King Solomon. In particular the Ain Dara (archaeological site), Ain Dara temple in northern Syria with a similar age, size, plan and decorations.[33]

Freemasonry

Rituals in Freemasonry refer to King Solomon and the building of his Temple.[34] Masonic buildings, where Lodge members meet, are sometimes called 'temples'; an allegoric reference to King Solomon's Temple.[35]

Kabbalah

Kabbalah views the design of the Temple of Solomon as representative of the metaphysical world and the descending light of the creator through Sefirot of the Tree of Life. The levels of the outer, inner and priest's courts represent three lower worlds of Kabbalah. The Boaz and Jachin pillars at the entrance of the temple represent the active and passive elements of the world of Atziluth. The original menorah and its seven branches represent the seven lower Sephirot of the Tree of Life. The veil of the Holy of Holies and the inner part of the temple represent the Veil of the Abyss on the Tree of Life, behind which the Shekhinah or Divine Presence hovers.[36]

Islam

The Temple in Jerusalem is mentioned in verse 7 of the surah Al-Isra in the Quran; commentators of Quran such as Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur [37] postulate that this verse refers specifically to the Temple of Solomon.

Popular culture

Solomon's Temple appears in Solomon and Sheba (1959) and in the novel King Solomon's Mines (1885). It also appears in the video game Assassin's Creed where the main character Altaïr Ibn-La'Ahad deal with Robert de Sablé.[38][39] It appears too on Assassin's Creed Unity (2014) where the Knight Templar Jacques de Molay is burned and died.[40][41]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Josephus, Jew. Ant. 10.8.5

- ↑ "Science & Nature – Horizon". BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ↑ Dever, William G. Did God Have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Wm B. Eerdmans. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0802828521. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ↑ Stevens, Marty E. (2006), Temples, tithes, and taxes: the temple and the economic life of ancient Israel, Hendrickson Publishers, p. 3, ISBN 1-56563-934-0

- ↑ Clifford Mark McCormick (2002). Palace and Temple: A Study of Architectural and Verbal Icons. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-3-11-017277-5.

- ↑ 1 Kings 6:38

- ↑ Achtemeier, Paul J.; Boraas, Roger S. (1996), The HarperCollins Bible Dictionary, San Francisco: HarperOne, p. 1096

- ↑ "Temple In Rabbinical Literature". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- ↑ Yeisen, Yosef (2004), Miraculous journey: a complete history of the Jewish people from creation to the present, Targum Press, p. 56, ISBN 1-56871-323-1

- ↑ Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Ab, Ninth Day of". Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ According to Finkelstein in The Bible Unearthed, the description of the temple is remarkably similar to that of surviving remains of Phoenician temples of the time, and it is certainly plausible, from the point of view of archaeology, that the temple was constructed to the design of Phoenicians.

- 1 2 3 4 De Vaux, Roland; McHugh, John, ed. (1961). Ancient Israel: Its Life and Institutions. NY: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer The Origins of Jewish Mysticism. 2011. p. 59: "Scholars have long observed that this three-part structure resembles the structure of Solomon's Temple as described in 1 Kings 6:3, 5: the hekhal (sanctuary), the devir (inner sanctuary) or qodesh ha-qodashim (Holy of Holies)..."

- ↑ Meir Ben-Dov, The Golden Age: Synagogues of Spain in History and Architecture, 2009: "Among Ashkenazic Jewry, even though these two were the main foci of the synagogue, the terms used for them were different. The hekhal (literally, "the Temple") was known as the aron ha-kodesh (literally, ..."

- 1 2 Pulpit Commentary on 1 Kings 8, accessed 2 October 2017

- ↑ 1 Kings 8:10-66

- ↑ Warren, Charles (1876). Underground Jerusalem: An Account of Some of the Principal Difficulties Encountered in Its Exploration and the Results Obtained. With a Narrative of an Expedition through the Jordan Valley and a Visit to the Samaritans. London: Richard Bentley.

- ↑ Langmead, Donald; Garnaut, Christine (2001). Encyclopedia of Architectural and Engineering Feats (3rd, illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576071120.

- ↑ Handy, Lowell (1997). The Age of Solomon: Scholarship at the Turn of the Millennium. Brill. pp. 493–94. ISBN 978-90-04-10476-1.

- 1 2 3 Finkelstein, Israel & Silberman, Neil Asher (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Simon & Schuster. pp. 128–29. ISBN 0-684-86912-8.

- ↑ T. C. Mitchell (1992). "Judah Until the Fall of Jerusalem". In John Boardman; I. E. S. Edwards; E. Sollberger; N. G. L. Hammond. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC. Cambridge University Press. p. 397. ISBN 978-0521227179.

- ↑ Myre, Greg (December 30, 2004). "Israel Indicts 4 in 'Brother of Jesus' Hoax and Other Forgeries". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Ivory pomegranate 'not Solomon's'". BBC News. December 24, 2004.

- ↑ Shanks, Hershel (November–December 2011). "Fudging with Forgeries". Biblical Archaeology Review. 37 (6): 56–58. ISSN 0098-9444.

- ↑ Shanks, Hershel (November–December 2012). "Authentic or Forged? What to Do When Experts Disagree". Biblical Archaeology Review. First Person (column). ISSN 0098-9444. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ "Building Remains From The Time Of The First Temple Were Exposed West Of The Temple Mount". Israel Antiquities Authority. March 13, 2008. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

a personal Hebrew seal made of a semi-precious stone that was apparently inlaid in a ring. The scarab-like seal is elliptical and measures c. 1.1 cm (0.4 in) x 1.4 cm (0.6 in). The surface of the seal is divided into three strips separated by a double line: in the upper strip is a chain decoration in which there are four pomegranates and in the two bottom strips is the name of the owner of the seal, engraved in ancient Hebrew script. It reads: לנתניהו בן יאש ([belonging] to Netanyahu ben Yaush). The two names are known in the treasury of biblical names: the name נתניהו (Netanyahu) is mentioned a number of times in the Bible (in the Book of Jeremiah and in Chronicles) and the name יאש (Yaush) appears in the Lachish letters. The name Yaush, like the name יאשיהו (Yoshiyahu) is, in the opinion of Professor Shmuel Ahituv, derived from the root או"ש which means “he gave a present” (based on Arabic and Ugaritic). It is customary to assume that the owners of personal seals were people that held senior governmental positions. It should nevertheless be emphasized that this combination of names – נתניהו בן יאוש (Netanyahu ben Yaush) – was unknown until now.

- ↑ Shragai, Nadav (October 19, 2006). "Temple Mount dirt uncovers First Temple artifacts". Haaretz.

- ↑ "Temple Mount First Temple Period Discoveries". The Friends of the Israel Antiquities Authority. Retrieved 2009-10-05.

- ↑ Milstein, Mati (October 23, 2007). "Solomon's Temple Artifacts Found by Muslim Workers". National Geographic News.

- ↑ Avraham Negev & Shimon Gibson (2001). Arad (Tel). Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. New York and London: Continuum. p. 43. ISBN 0-8264-1316-1.

- ↑ Mazar, Amihai. “The Divided Monarchy: Comments on Some Archaeological Issues.” pp. 159–80 in The Quest for the Historical Israel: Debating Archaeology and the History of Early Israel (Archaeology and Biblical Studies) Society of Biblical Literature (Sep 2007) ISBN 978-1-58983-277-0 p. 176

- ↑ "Ancient Sudan~ Nubia: Investigating the Origin of the Ancient Jewish Community at Elephantine: A Review".

- ↑ "Searching for the Temple of King Solomon". Biblical Archaeology Society. 6 January 2017.

- ↑ "Lodge Chelmsford No 261". Lodgechelmsford.com. Retrieved 2015-01-29.

- ↑ Invalid Input. "Freemasons NSW & ACT – Home". Masons.org.au. Retrieved 2015-01-29.

- ↑ The Way of Kabbalah, Warren Kenton, Z'ev ben Shimon Halevi, Weiser Books, 1976, p. 24.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, Muhammad al-Tahir. "al-Tahrir wa'l-tanwir". Al-Dar Al-Tunasia Publication. Tunisia. 1984. vol. 15, p. 13

- ↑ Bowden, Oliver (June 23, 2011). Assassin's Creed: The Secret Crusade. Penguin UK. p. 464. ISBN 9780141966717.

- ↑ Dansereau, François; Lowe, Ivan; Nadiger, James; Podar, Nitai; Sutton, Megan; Whelton-Pane, Johathan; Wright, William (November 2011). Assassin's Creed Encyclopedia. UbiWorkshop. p. 256. ISBN 978-2-924006-03-0.

- ↑ Worley, Seth. "Assassin's Creed Unity (Video Game Review)". BioGamer Girl Magazine. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ↑ Bowden, Oliver (November 20, 2014). Assassin's Creed: Unity. Penguin UK. p. 480. ISBN 9781405918855.

References

- De Vaux, Roland (1961). John McHugh, ed. Ancient Israel: Its Life and Institutions. NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Draper, Robert (Dec 2010). "Kings of Controversy". National Geographic: 66–91. ISSN 0027-9358. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Neil Asher Silberman (2006). David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-4362-5.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision.

- Glueck, Nelson (Feb 1944). "On the Trail of King Solomon's Mines". National Geographic. 85 (2): 233–56. ISSN 0027-9358.

- Goldman, Bernard (1966). The Sacred Portal: a primary symbol in ancient Judaic art. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

It has a detailed account and treatment of Solomon's Temple and its significance.

- Hamblin, William; David Seely (2007). Solomon's Temple: Myth and History. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-25133-9.

- Mazar, Benjamin (1975). The Mountain of the Lord. NY: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04843-2.

- Young, Mike. "Temple Measurements and Photo recreations".

Further reading

- 21st century resources

- Barker, Margaret (2004), Temple Theology, an introduction, London: The Society For Promoting Christian Knowledge, ISBN 028105634X .

- Vaughn, Andrew G.; Killebrew, Ann E., eds. (2003), Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period, Society of Biblical Literature .

- Stevens, Marty E. (2006), Temples, tithes, and taxes: the temple and the economic life of ancient Israel, Hendrickson Publishers, ISBN 1-56563-934-0 .

- Dever, William G. (2001-05-10), What Did The Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?, Wm. B. Eerdmans .

- Jones, Floyd Nolen (1993–2004), The Chronology Of The Old Testament, New Leaf Publishing Group .

- Post-1945 resources

- Elizabeth Bloch-Smith, Who is the King of Glory?: Solomon's Temple and its Symbolism in Michael D. Coogan, J. Cheryl Exum, Lawrence E. Stager (eds), "Scripture and Other Artifacts: Essays in Honor of Philip J. King" (Westminster John Knox, 1994)

- Gershon Galil, "The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah" (Brill, 1996)

- Joseph Blenkinsopp, "Sage, Priest, Prophet: Religious and Intellectual Leadership in Ancient Israel" (Westminster John Knox Press, 1995)

- Jeremy Hughes, "Secrets of the times: myth and history in biblical chronology" (Sheffield Academic Press, 1990)

- Edwin R. Thiele, "The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings" (Zondervan, 1983)

- Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard (eds), "Mercer Dictionary of the Bible" (Mercer University Press, 1990)

- Pre-1945 resources

External links

| Library resources about Solomon's Temple |