Aelia Capitolina

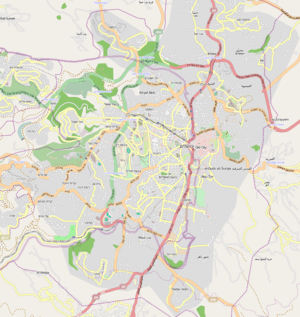

Shown within Jerusalem | |

| Location | Jerusalem |

|---|---|

| Region | Jerusalem Corpus Separatum |

| Coordinates | 31°46′32″N 35°13′52″E / 31.775689°N 35.23104°E |

| AD 130 – AD 324-325 | |

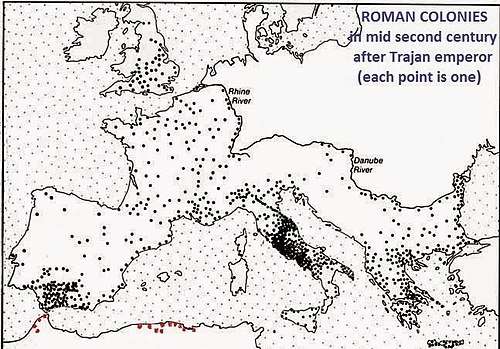

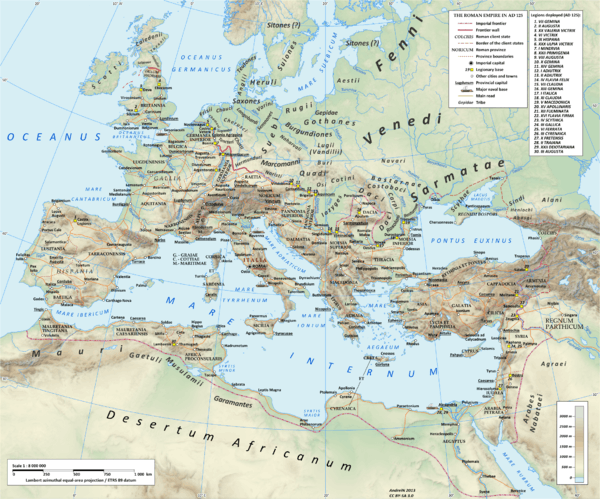

Jerusalem in the Roman empire under Hadrian showing the location of the Roman legions | |

| Preceded by | Jerusalem during the Early Roman period |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Jerusalem during the Byzantine period |

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

-Aerial-Jerusalem-Temple_Mount-Temple_Mount_(south_exposure).jpg) |

| Sieges |

| Places |

| Positions |

| Other topics |

|

|

Aelia Capitolina (/ˈiːliə

Name

Aelia came from Hadrian's nomen gentile, Aelius, while Capitolina meant that the new city was dedicated to Jupiter Capitolinus, to whom a temple was built on the site of the former Jewish temple, the Temple Mount, but which had before Herod been reconsecrated to Zeus under Antiochus IV Epiphanes and caused the Maccabean Revolt—which resulted in the Jewish-Roman alliance.[1] (The Latin name Aelia is the source of the much later Arabic term Iliyā' (إلياء), a 7th-century Islamic name for Jerusalem.)

Foundation

Jerusalem, once heavily rebuilt by Herod, was still in ruins following the decisive siege of the city, as part of the First Jewish–Roman War in 70 AD. Josephus – a contemporary historian and proponent of the Judean cause who was born in Jerusalem and fought the Romans in that war – reports that "Jerusalem ... was so thoroughly razed to the ground by those that demolished it to its foundations, that nothing was left that could ever persuade visitors that it had once been a place of habitation.".[4] The Talmud (Makkot) tells of Rabbi Akiva and several other sages visiting the ruins of Jerusalem. His colleagues were aggrieved at seeing a fox scuttling out of what had been the Temple's Holy of Holies as an indication of the desolation, while Akiva laughed, telling them through what many believe to be divine inspiration that one day the Temple will be rebuilt. Many Jews today view the reestablishment of Jewish sovereignty in the State of Israel as a partial fulfillment of that pledge.

When the Roman Emperor Hadrian vowed to rebuild Jerusalem from the wreckage in 130 AD, he considered reconstructing Jerusalem as a gift to the Jewish people. The Jews awaited with hope, but after Hadrian visited Jerusalem, he was discouraged from doing so by a Samaritan.[5] He then decided to rebuild the city as a Roman colony which would be inhabited by his legionaries.[6] Hadrian's new city was to be dedicated to himself, and certain Roman gods, in particular Jupiter Capitolinus.[7]

The Jewish Bar Kokhba revolt, which took the Romans three years to suppress, enraged Hadrian, and he became determined to erase Judaism from the province. Circumcision was forbidden, Iudaea province was renamed Syria Palaestina and Jews expelled from the city. There is a controversy as to whether the anti-Jewish decrees followed the Bar Kokhba revolt or preceded it and were actually the cause of the revolt.[5]

Indeed, following the Bar Kokhba revolt, Emperor Hadrian renamed Iudaea Province with the new name of Syria Palaestina, dispensing with the name of Judea.[8] The city was renamed "Aelia Capitolina",[9] and rebuilt it in the style of a typical Roman town. Jews were prohibited from entering the city on pain of death, except for one day each year, during the holiday of Tisha B'Av. Taken together, these measures[10][11][12] (which also affected Jewish Christians)[13] essentially "secularized" the city.[14] The ban was maintained until the 7th century,[15] though Christians would soon be granted an exemption: during the 4th century, the Roman Emperor Constantine I ordered the construction of Christian holy sites in the city, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Burial remains from the Byzantine period are exclusively Christian, suggesting that the population of Jerusalem in Byzantine times probably consisted only of Christians.[16]

.jpg)

Till the time of Constantine, and for at least two centuries later, Aelia remained the official name and usual geographical designation ; was still longer continued in Christian writings; and even passed over into Arabic as "Iliyā".[17]

In the fifth century, the eastern continuation of the Roman Empire that was ruled from the recently renamed Constantinople, maintained control of the city. Within the span of a few decades, the city shifted from Byzantine to Persian rule, then back to Roman-Byzantine dominion. Following Sassanid Khosrau II's early seventh century push through Syria, his generals Shahrbaraz and Shahin attacked Jerusalem (Persian: Dej Houdkh) aided by the Jews of Palaestina Prima, who had risen up against the Byzantines.[18]

In the Siege of Jerusalem of 614 AD, after 21 days of relentless siege warfare, Jerusalem was captured. Byzantine chronicles relate that the Sassanids and Jews slaughtered tens of thousands of Christians in the city, many at the Mamilla Pool, and destroyed their monuments and churches, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The conquered city would remain in Sassanid hands for some fifteen years until the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius reconquered it in 629.[19]

Byzantine Jerusalem was conquered by the Arab armies of Umar ibn al-Khattab in 638 AD.[20] Among Muslims of Islam's earliest era it was referred to as Madinat bayt al-Maqdis ("City of the Temple")[21] which was restricted to the Temple Mount. The rest of the city was called "Iliya", reflecting the Roman name given the city following the destruction of 70 CE: Aelia Capitolina".[22]

Christianity

According to Eusebius, the Jerusalem church was scattered twice, in 70 and 135, with the difference that from 70-130 the bishops of Jerusalem have evidently Jewish names, whereas after 135 the bishops of Aelia Capitolina appear to be Greeks.[23] Eusebius' evidence for continuation of a church at Aelia Capitolina is confirmed by the Bordeaux Pilgrim.[24]

Plan of the city

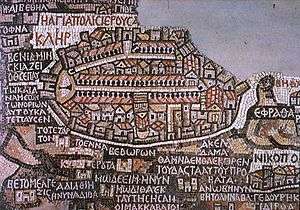

The Madaba Map depiction of 6th-century Jerusalem has the Cardo Maximus, the town’s main street, beginning at the northern gate, today's Damascus Gate, and traversing the city in a straight line from north to south to "Nea Church"

The Madaba Map depiction of 6th-century Jerusalem has the Cardo Maximus, the town’s main street, beginning at the northern gate, today's Damascus Gate, and traversing the city in a straight line from north to south to "Nea Church"- The two pairs of main roads - the cardines (north-south) and decumani (east-west) - in Aelia Capitolina.

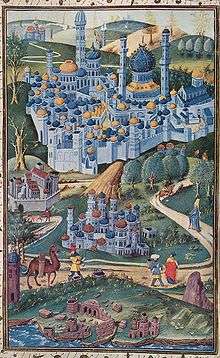

1455 painting of the Holy Land. Jerusalem is viewed from the west; the Dome of the Rock still retains its octagonal shape, to the right stands Al-Aqsa, shown as a church.

1455 painting of the Holy Land. Jerusalem is viewed from the west; the Dome of the Rock still retains its octagonal shape, to the right stands Al-Aqsa, shown as a church.

The city was without walls, protected by a light garrison of the Tenth Legion, during the Late Roman Period. The detachment at Jerusalem, which apparently encamped all over the city's western hill, was responsible for preventing Jews from returning to the city. Roman enforcement of this prohibition continued through the 4th century.

The urban plan of Aelia Capitolina was that of a typical Roman town wherein main thoroughfares crisscrossed the urban grid lengthwise and widthwise.[25] The urban grid was based on the usual central north-south road (cardo) and central east-west route (decumanus). However, as the main cardo ran up the western hill, and the Temple Mount blocked the eastward route of the main decumanus, a second pair of main roads was added; the secondary cardo ran down the Tyropoeon Valley, and the secondary decumanus ran just to the north of the Temple Mount. The main Hadrianic cardo terminated not far beyond its junction with the decumanus, where it reached the Roman garrison's encampment, but in the Byzantine era it was extended over the former camp to reach the southern walls of the city.

The two cardines converged near the Damascus Gate, and a semicircular piazza covered the remaining space; in the piazza a columnar monument was constructed, hence the Arabic name for the gate - Bab el-Amud (Gate of the Column). Tetrapylones were constructed at the other junctions between the main roads.

This street pattern has been preserved in the Old City of Jerusalem to the present. The original thoroughfare, flanked by rows of columns and shops, was about 73 feet (22 meters) wide, but buildings have extended onto the streets over the centuries, and the modern lanes replacing the ancient grid are now quite narrow. The substantial remains of the western cardo have now been exposed to view near the junction with Suq el-Bazaar, and remnants of one of the tetrapylones are preserved in the 19th century Franciscan chapel at the junction of the Via Dolorosa and Suq Khan ez-Zeit.

As was standard for new Roman cities, Hadrian placed the city's main Forum at the junction of the main cardo and decumanus, now the location for the (smaller) Muristan. Adjacent to the Forum, at the junction of the same cardo, and the other decumanus, Hadrian built a large temple to Venus, which later became the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; despite 11th century destruction, which resulted in the modern Church having a much smaller footprint, several boundary walls of Hadrian's temple have been found among the archaeological remains beneath the Church.[26] The Struthion Pool lay in the path of the northern decumanus, so Hadrian placed vaulting over it, added a large pavement on top, and turned it into a secondary Forum;[27] the pavement can still be seen under the Convent of the Sisters of Zion.[27]

See also

Notes

- 1 2

- ↑ "Aelia Capitolina". Ancient Numismatic Mythology. AncientCoinage.Org. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ Map of the early Arab dominions, showing Iliya

- ↑ Josephus, Jewish War, 7:1:1

- 1 2 Peter Schäfer (2 September 2003). The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World: The Jews of Palestine from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest. Routledge. pp. 146–. ISBN 1-134-40316-X.

- ↑ Benjamin Isaac, The Near East under Roman Rule: Selected Papers (Leiden: Brill 1998)

- ↑ Gray, John (1969). A history of Jerusalem. London: Hale. p. 59. ISBN 0709103646. OCLC 53301.

- ↑ Elizabeth Speller, Following Hadrian: A Second-Century Journey Through the Roman Empire, p. 218, at Google Books, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 218

- ↑ Lehmann, Clayton Miles. "Palestine: People and Places". The On-line Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces. The University of South Dakota. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer (2003). The Bar Kokhba war reconsidered: new perspectives on the second Jewish revolt against Rome. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-3-16-148076-8. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ Lehmann, Clayton Miles (22 February 2007). "Palestine: History". The On-line Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces. The University of South Dakota. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- ↑ Cohen, Shaye J. D. (1996). "Judaism to Mishnah: 135–220 C.E". In Hershel Shanks. Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism: A Parallel History of their Origins and Early Development. Washington DC: Biblical Archaeology Society. p. 196.

- ↑ Emily Jane Hunt, Christianity in the second century: the case of Tatian, p. 7, at Google Books, Psychology Press, 2003, p. 7

- ↑ E. Mary Smallwood The Jews under Roman rule: from Pompey to Diocletian : a study in political relations, p. 460, at Google Books BRILL, 1981, p. 460.

- ↑ Zank, Michael. "Byzantian Jerusalem". Boston University. Retrieved 1 February 2007.

- ↑ Gideon Avni, The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach, p. 144, at Google Books, Oxford University Press 2014 p.144.

- ↑ "The Name Jerusalem and its History" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-12-12.

- ↑ Conybeare, Frederick C. (1910). The Capture of Jerusalem by the Persians in 614 AD. English Historical Review 25. pp. 502–517.

- ↑ Rodney Aist,The Christian Topography of Early Islamic Jerusalem,Brepols Publishers, 2009 p.56:'Persian control of Jerusalem lasted from 614 to 629'.

- ↑ Dan Bahat (1996). The Illustrated Atlas of Jerusalem. p. 71.

- ↑ Ben-Dov, M. Historical Atlas of Jerusalem. Translated by David Louvish. New York: Continuum, 2002, p. 171

- ↑ Linquist, J.M., The Temple of Jerusalem, Praeger, London, 2008, p. 184

- ↑ "Jerusalem in Early Christian Thought" p75 Explorations in a Christian theology of pilgrimage ed Craig G. Bartholomew, Fred Hughes

- ↑ Richard Bauckham "The Christian Community of Aelia Capitolina" in The Book of Acts in Its Palestinian Setting p310.

- ↑ The Cardo Archived December 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Hebrew University

- ↑ Virgilio Corbo, The Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (1981)

- 1 2 Pierre Benoit, The Archaeological Reconstruction of the Antonia Fortress, in Jerusalem Revealed (edited by Yigael Yadin), (1976)

External links

- Detailed description (including map) of the city of Aelia Capitolina

- Pictures of the cave where it is believed by Christians that Jesus was buried and from which it is believed he resurrected and a picture of the remains of the walls of the Temple of Venus previously constructed on that site by the Emperor Hadrian

- "Archaeologists bringing Jerusalem's ancient Roman city back to life" by Nir Hasson, Ha'aretz, February 21, 2012

Coordinates: 31°46′32″N 35°13′52″E / 31.775689°N 35.231040°E