Tiberias

Tiberias

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | ||

| • Also spelled | Tveria, Tveriah (unofficial) | |

Tiberias in August 2011 | ||

| ||

Tiberias | ||

| Coordinates: 32°47′40″N 35°32′00″E / 32.79444°N 35.53333°ECoordinates: 32°47′40″N 35°32′00″E / 32.79444°N 35.53333°E | ||

| Grid position | 201/243 PAL | |

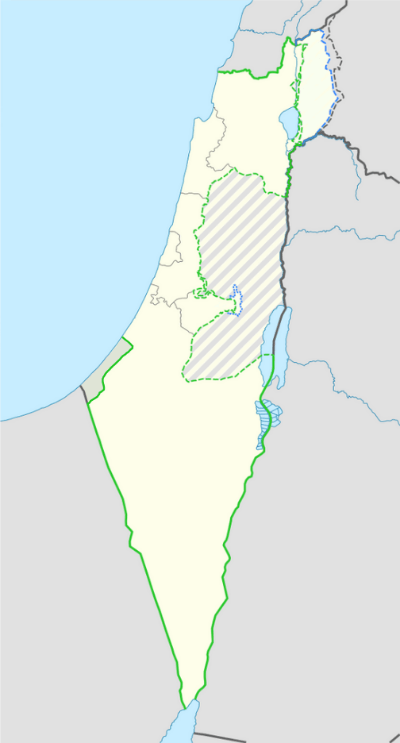

| Country | Israel | |

| District | Northern | |

| Founded |

1200 BCE (Biblical Rakkath) 20 CE (Herodian city) | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | City (from 1948) | |

| • Mayor | Yosef Ben David | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 10,872 dunams (10.872 km2 or 4.198 sq mi) | |

| Population (2017)[1] | ||

| • Total | 43,664 | |

| • Density | 4,000/km2 (10,000/sq mi) | |

| Name meaning | City of Tiberius | |

| Website | www.tiberias.muni.il | |

Tiberias (/taɪˈbɪəriəs/; Hebrew: טְבֶרְיָה, Tverya, ![]()

Tiberias was held in great respect in Judaism from the middle of the 2nd century CE[3] and since the 16th century has been considered one of Judaism's Four Holy Cities, along with Jerusalem, Hebron and Safed.[4] In the 2nd–10th centuries, Tiberias was the largest Jewish city in the Galilee and the political and religious hub of the Jews of Israel. Its immediate neighbour to the south, Hammat Tiberias, which is now part of modern Tiberias, has been known for its hot springs, believed to cure skin and other ailments, for some two thousand years.[5]

History

Jewish biblical tradition

Jewish tradition holds that Tiberias was built on the site of the ancient Israelite village of Rakkath or Rakkat, first mentioned in the Book of Joshua.[6][7] In Talmudic times, the Jews still referred to it by this name.[8]

Herodian period

Tiberias was founded sometime around 20 CE in the Herodian Tetrarchy of Galilee and Peraea by the Roman client king Herod Antipas, son of Herod the Great. Herod Antipas made it the capital of his realm in the Galilee and named it for the Roman Emperor Tiberius.[6] The city was built in immediate proximity to a spa which had developed around 17 natural mineral hot springs, Hammat Tiberias. Tiberias was at first a strictly pagan city, but later became populated mainly by Jews, with its growing spiritual and religious status exerting a strong influence on balneological practices.[5] Conversely, in The Antiquities of the Jews, the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus calls the village with hot springs Emmaus, today's Hammat Tiberias, located near Tiberias.[2] This name also appears in The Wars of the Jews.[9]

In the days of Herod Antipas, some of the most religiously orthodox Jews, who were struggling against the process of Hellenization, which had affected even some priestly groups, refused to settle there: the presence of a cemetery rendered the site ritually unclean for the Jews and particularly for the priestly caste. Antipas settled many non-Jews there from rural Galilee and other parts of his domains in order to populate his new capital, and built a palace on the acropolis.[10] The prestige of Tiberias was so great that the Sea of Galilee soon came to be named the Sea of Tiberias; however, the Jewish population continued to call it 'Yam Ha-Kineret', its traditional name.[10] The city was governed by a city council of 600 with a committee of 10 until 44 CE when a Roman procurator was set over the city after the death of Herod Agrippa I.[10]

Roman period

Tiberias is mentioned in John 6:23 as the location from which boats had sailed to the eastern side of the Sea of Galilee. The crowd seeking Jesus after the miraculous feeding of the 5000 used these boats to travel back to Capernaum on the north-western part of the sea.

Under the Roman Empire, the city was known by its Greek name Τιβεριάς (Tiberiás, Modern Greek Τιβεριάδα Tiveriáda), an adaptation of the taw-suffixed Semitic form that preserved its feminine grammatical gender. In 61 CE Herod Agrippa II annexed the city to his kingdom whose capital was Caesarea Philippi.[11] During the First Jewish–Roman War, the seditious took control of the city and destroyed Herod's palace, and were able to prevent the city from being pillaged by the army of Agrippa II, the Jewish ruler who had remained loyal to Rome.[10][12] Eventually, the seditious were expelled from Tiberias, and while most other cities in the provinces of Judaea, Galilee and Idumea were razed, Tiberias was spared this fate because its inhabitants had decided not to fight against Rome.[10][13] It became a mixed city after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE; with Judea subdued, the surviving southern Jewish population migrated to the Galilee.[14][15]

.jpg)

There is no direct indication that Tiberias, as well as the rest of Galilee, took part in the Bar Kokhba revolt of 132–136 CE, thus allowing it to exist, despite a heavy economic decline due to the war. Following the expulsion of Jews from Judea after 135 CE, Tiberias and its neighbor Sepphoris (Hebrew name: Tzippori) became the major Jewish cultural centres, competing within the Jewish world for status and recognition with Babylon, Alexandria, Aleppo and the Persian Empire.

In 145 CE, Rabbi Simeon bar Yochai, who was very familiar with the Galilee, hiding there for over a decade, "cleansed the city of ritual impurity",[11] allowing the Jewish leadership to resettle there from the Judea Province, where they were fugitives. The Sanhedrin, the Jewish court, also fled from Jerusalem during the Great Jewish Revolt against Rome, and after several attempted moves, in search of stability, eventually settled in Tiberias in about 150 CE.[10][15] It was to be its final meeting place before its disbanding in the early Byzantine period. When Johanan bar Nappaha (d. 279) settled in Tiberias, the city became the focus of Jewish religious scholarship in the land. The Mishnah, the collected theological discussions of generations of rabbis in the Land of Israel – primarily in the academies of Tiberias and Caesarea – was probably compiled in Tiberias by Rabbi Judah haNasi around 200 CE. The Jerusalem Talmud would follow being compiled by Rabbi Jochanan between 230–270 CE.[15] Tiberias' 13 synagogues served the spiritual needs of a growing Jewish population.[10]

Byzantine period

In the 6th century Tiberias was still the seat of Jewish religious learning. In light of this, a letter of Syriac bishop Simeon of Beth Arsham urged the Christians of Palaestina to seize the leaders of Judaism in Tiberias, to put them to the rack, and to compel them to command the Jewish king, Dhu Nuwas, to desist from persecuting the Christians in Najran.[16]

In 614, Tiberias was the site where, during the final Jewish revolt against the Byzantine Empire, parts of the Jewish population supported the Persian invaders; the Jewish rebels were financed by Benjamin of Tiberias, a man of immense wealth; according to Christian sources, during the revolt Christians were massacred and churches destroyed. In 628, the Byzantine army returned to Tiberias upon the surrender of Jewish rebels and the end of the Persian occupation after they were defeated in the battle of Nineveh. A year later, influenced by radical Christian monks, Emperor Heraclius instigated a wide-scale slaughter of the Jews, which practically emptied Galilee of most its Jewish population, with survivors fleeing to Egypt.

Early Muslim period

Tiberias, or Tabariyyah in Arab transcription, was "conquered by (the Arab commander) Shurahbil in the year 634/15 [CE/AH] by capitulation; one half of the houses and churches were to belong to the Muslims, the other half to the Christians."[17] Since 636 CE, Tiberias served as the regional capital, until Beit She'an took its place, following the Rashidun conquest. The Caliphate allowed 70 Jewish families from Tiberias to form the core of a renewed Jewish presence in Jerusalem and the importance of Tiberias to Jewish life declined.[11] The caliphs of the Umayyad Dynasty built one of its square-plan palaces on the waterfront to the north of Tiberias, at Khirbat al-Minya. Tiberias was revitalised in 749, after Bet Shean was destroyed in an earthquake.[11] An imposing mosque, 90 metres (300 feet) long by 78 metres (256 feet) wide, resembling the Great Mosque of Damascus, was raised at the foot of Mount Berenice next to a Byzantine church, to the south of the city, as the eighth century ushered in Tiberias's golden age, when the multicultural city may have been the most tolerant of the Middle East.[18] Jewish scholarship flourished from the beginning of the 8th century to the end of the 10th., when the oral traditions of ancient Hebrew, still in use today, were codified. One of the leading members of the Tiberian masoretic community was Aaron ben Moses ben Asher, who refined the oral tradition now known as Tiberian Hebrew. Ben Asher is also credited with putting the finishing touches on the Aleppo Codex, the most accurate existing manuscript of the Hebrew scriptures.

The Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi writing in 985, describes Tiberias as a hedonistic city afflicted by heat:-'For two months they dance; for two months they gobble; for two months they swat; for two months they go about naked; for two months they play the reed flute; and for two months they wallow in the mud.[18] As "the capital of Jordan Province, and a city in the Valley of Canaan...The town is narrow, hot in summer and unhealthy...There are here eight natural hot baths, where no fuel need be used, and numberless basins besides of boiling water. The mosque is large and fine, and stands in the market-place. Its floor is laid in pebbles, set on stone drums, placed close one to another." According to Muqaddasi, those who suffered from scab or ulcers, and other such diseases came to Tiberias to bathe in the hot springs for three days. "Afterwards they dip in another spring which is cold, whereupon...they become cured."[19]

In 1033 Tiberias was again destroyed by an earthquake.[11] A further earthquake in 1066 toppled the great mosque.[18] Nasir-i Khusrou visited Tiberias in 1047, and describes a city with a "strong wall" which begins at the border of the lake and goes all around the town except on the water-side. Furthermore, he describes

numberless buildings erected in the very water, for the bed of the lake in this part is rock; and they have built pleasure houses that are supported on columns of marble, rising up out of the water. The lake is very full of fish. [] The Friday Mosque is in the midst of the town. At the gate of the mosque is a spring, over which they have built a hot bath. [] On the western side of the town is a mosque known as the Jasmine Mosque (Masjid-i-Yasmin). It is a fine building and in the middle part rises a great platform (dukkan), where they have their mihrabs (or prayer-niches). All round those they have set jasmine-shrubs, from which the mosque derives its name.[20]

Crusader period

During the First Crusade Tiberias was occupied by the Franks soon after the capture of Jerusalem. The city was given in fief to Tancred, who made it his capital of the Principality of Galilee in the Kingdom of Jerusalem; the region was sometimes called the Principality of Tiberias, or the Tiberiad.[21] In 1099 the original site of the city was abandoned, and settlement shifted north to the present location.[11] St. Peter's Church, originally built by the Crusaders, is still standing today, although the building has been altered and reconstructed over the years.

In the late 12th century Tiberias' Jewish community numbered 50 Jewish families, headed by rabbis,[22] and at that time the best manuscripts of the Torah were said to be found there.[16] In the 12th-century, the city was the subject of negative undertones in Islamic tradition. A hadith recorded by Ibn Asakir of Damascus (d. 1176) names Tiberias as one of the "four cities of hell."[23] This could have been reflecting the fact that at the time, the town had a notable non-Muslim population.[24]

In 1187, Saladin ordered his son al-Afdal to send an envoy to Count Raymond of Tripoli requesting safe passage through his fiefdom of Galilee and Tiberias. Raymond was obliged to grant the request under the terms of his treaty with Saladin. Saladin's force left Caesarea Philippi to engage the fighting force of the Knights Templar. The Templar force was destroyed in the encounter. Saladin then besieged Tiberias; after six days the town fell. On July 4, 1187 Saladin defeated the Crusaders coming to relieve Tiberias at the Battle of Hattin, 10 kilometres (6 miles) outside the city.[25] However, during the Third Crusade, the Crusaders drove the Muslims out of the city and reoccupied it.

Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, (Maimonides) also known as Rambam, a leading Jewish legal scholar, philosopher and physician of his period, died in 1204 in Egypt and was later buried in Tiberias. His tomb is one of the city's important pilgrimage sites. Yakut, writing in the 1220s, described Tiberias as a small town, long and narrow. He also describes the "hot salt springs, over which they have built Hammams which use no fuel."

Mamluk period

In 1265 the Crusaders were driven from the city by the Egyptian Mamluks, who ruled Tiberias until the Ottoman conquest in 1516.[11]

Ottoman period

During the 16th century, Tiberias was a small village. Italian Rabbi Moses Bassola visited Tiberias during his trip to Palestine in 1522. He said on Tiberias that "...it was a big city... and now it is ruined and desolate". He described the village there, in which he said there were "ten or twelve" Muslim households. The area, according to Bassola, was dangerous "because of the Arabs", and in order to stay there, he had to pay the local governor for his protection.[26]

As the Ottoman Empire expanded along the southern Mediterranean coast under Great Sultan Selim I, the Reyes Católicos (Catholic Monarchs) began establishing Inquisition commissions. Many Conversos, (Marranos and Moriscos) and Sephardi Jews fled in fear to the Ottoman provinces, settling at first in Constantinople, Salonika, Sarajevo, Sofia and Anatolia. The Sultan encouraged them to settle in Palestine.[11][27][28] In 1558, a Portuguese-born marrano, Doña Gracia, was granted tax collecting rights in Tiberias and its surrounding villages by Suleiman the Magnificent. She envisaged the town becoming a refuge for Jews and obtained a permit to establish Jewish autonomy there.[29] In 1561 her nephew Joseph Nasi, Lord of Tiberias,[30] encouraged Jews to settle in Tiberias.[31] Securing a firman from the Sultan, he and Joseph ben Adruth rebuilt the city walls and lay the groundwork for a textile (silk) industry, planting mulberry trees and urging craftsmen to move there.[31] Plans were made for Jews to move from the Papal States, but when the Ottomans and the Republic of Venice went to war, the plan was abandoned.[31]

At the end of the century (1596), the village of Tiberias had 54 households: 50 families and 4 bachelors. All were Muslims. The main product of the village at that time was wheat, while other products included barley, fruit, fish, goats and bee hives; the total revenue were 3,360 akçe.[32]

In 1624, when the Sultan recognized Fakhr-al-Din II as Lord of Arabistan (from Aleppo to the borders of Egypt),[33] the Druze leader made Tiberias his capital.[11] The 1660 destruction of Tiberias by the Druze resulted in abandonment of the city by its Jewish community,[34][35] Unlike Tiberias, the nearby city of Safed recovered from its destruction,[36] and wasn't entirely abandoned,[37] remaining an important Jewish center in the Galilee.

In the 1720s, the Arab ruler Zahir al-Umar, of the Zaydani clan, fortified the town and signed an agreement with the neighboring Bedouin tribes to prevent looting. Accounts from that time tell of the great admiration people had for Zahir, especially his war against bandits on the roads. Richard Pococke, who visited Tiberias in 1727, witnessed the building of a fort to the north of the city, and the strengthening of the old walls, attributing it to a dispute with the Pasha of Damascus.[38] Under instructions from the Ottoman Porte, Sulayman Pasha al-Azm of Damascus laid siege to Tiberias in 1742, with the intention of eliminating Zahir, but his siege was unsuccessful. In the following year, Sulayman set out to repeat the attempt with even greater reinforcements, but he died en route.[39]

Under Zahir's patronage, Jewish families were encouraged to settle in Tiberias.[40] He invited Rabbi Chaim Abulafia of Smyrna to rebuild the Jewish community.[41] The synagogue he built still stands today, located in the Court of the Jews.[42][43]

In 1775, Ahmed el-Jazzar "the Butcher" brought peace to the region with an iron fist.[11] In 1780, many Polish Jews settled in the town.[41] During the 18th and 19th centuries it received an influx of rabbis who re-established it as a center for Jewish learning.[44] Around 600 people, including nearly 500 Jews,[41] died when the town was devastated by the 1837 Galilee earthquake.[11] Rabbi Haim Shmuel Hacohen Konorti, born in Spain in 1792, settled in Tiberias at the age of 45 and was a driving force in the restoration of the city.[45]

However, an American expedition reported that Tiberias was still in a state of disrepair in 1847/1848.[46]

Dr. Torrance's hospital

In 1885, a Scottish doctor and minister, David Watt Torrance, opened a mission hospital in Tiberias that accepted patients of all races and religions.[47] In 1894, it moved to larger premises at Beit abu Shamnel abu Hannah. In 1923 his son, Dr. Herbert Watt Torrance, was appointed head of the hospital. After the establishment of the State of Israel, it became a maternity hospital supervised by the Israeli Department of Health. After its closure in 1959, the building became a guesthouse until 1999, when it was renovated and reopened as the Scots Hotel.[48][49][50]

British Mandate

Initially the relationship between Arabs and Jews in Tiberias was good, with few incidents occurring in the Nebi Musa riots and the disturbances throughout Palestine in 1929.[11] The first modern spa was built in 1929.[5]

The landscape of the modern town was shaped by the great flood of November 11, 1934. Deforestation on the slopes above the town combined with the fact that the city had been built as a series of closely packed houses and buildings – usually sharing walls – built in narrow roads paralleling and closely hugging the shore of the lake. Flood waters carrying mud, stones, and boulders rushed down the slopes and filled the streets and buildings with water so rapidly that many people did not have time to escape; the loss of life and property was great. The city rebuilt on the slopes and the British Mandatory government planted the Swiss Forest on the slopes above the town to hold the soil and prevent similar disasters from recurring. A new seawall was constructed, moving the shoreline several yards out form the former shore.[51][52] In October 1938, Arab militants murdered 20 Jews in Tiberias during the 1936–39 Arab revolt in Palestine.[53]

Between the April 8–9, 1948, sporadic shooting broke out between the Jewish and Arab neighborhoods of Tiberias. On April 10, the Haganah launched a mortar barrage, killing some Arab residents.[54] The local National Committee refused the offer of the Arab Liberation Army to take over defense of the city, but a small contingent of outside irregulars moved in.[54] During April 10–17, the Haganah attacked the city and refused to negotiate a truce, while the British refused to intervene. Newly arrived Arab refugees from Nasir ad-Din told of the civilians there being killed, news which brought panic to the residents of Tiberias.[54] The Arab population of Tiberias (6,000 residents or 47.5% of the population) was evacuated under British military protection on 18 April 1948.[55]

The Jewish population looted the Arab areas and had to be suppressed by force by the Haganah and Jewish police, who killed or injured several looters.[56] On 30 December 1948, when David Ben-Gurion was staying in Tiberias, James Grover McDonald, the United States ambassador to Israel, requested to meet with him. McDonald presented a British ultimatum for Israeli troops to leave the Sinai peninsula, Egyptian territory. Israel rejected the ultimatum, but Tiberias became famous.[57]

Israel

The city of Tiberias has been almost entirely Jewish since 1948. Many Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews settled in the city, following the Jewish exodus from Arab countries in late 1940s and the early 1950s. Over time, government housing was built to accommodate much of the new population, like in many other development towns.

In 1959, during Wadi Salib riots, the "Union des Nords-africains led by David Ben Haroush, organised a large-scale procession walking towards the nice suburbs of Haifa creating little damage but a great fear within the population. This small incident was taken as an occasion to express the social malaise of the different Oriental communities in Israel and riots spread quickly to other parts of the country; mostly in towns with a high percentage of the population having North African origins like in Tiberias, in Beer-Sheva, in Migdal-Haemek".[58]

Over time, the city came to rely on tourism, becoming a major Galileean center for Christian pilgrims and internal Israeli tourism. The ancient cemetery of Tiberias and its old synagogues are also drawing religious Jewish pilgrims during religious holidays. PM Yitzhak Rabin mentioned the town in his memoirs on the occasion of signing the historic peace agreement with Egypt in 1979; and again at the Casablanca Conference in 1994.[59]

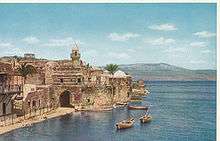

Tiberias consists of a small port on the shores of the Galilee lake for both fishing and tourist activities. Since the 1990s, the importance of the port for fishing was gradually decreasing, with the decline of the Tiberias lake level, due to continuing droughts and increased pumping of fresh water from the lake. It is expected that the lake of Tiberias will regain its original level (almost 6 metres (20 feet) higher than today), with the full operational capacity of Israeli desalination facilities by 2014.

Plans are underway to expand the city with a new neighborhood, Kiryat Sanz, built on a slope on the western side of the Kinneret and catering exclusively to Haredi Jews.[60]

Demographics

According to the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), as of December 2011, 41,700 inhabitants lived in Tiberias. According to CBS, as of December 2010 the city was rated 5 out of 10 on the socio-economic scale. The average monthly salary of an employee for the year 2009 was 4,845 NIS.[61] Almost all of the population is Jewish, in modern times, as the Arab population of Tiberias was evacuated under British military protection on 18 April 1948. Among the Jews, many are Mizrahi and Sephardic.

Demographic history

Tiberias had a large Jewish majority until the 7th century. No Christians or Jews were mentioned in the Ottoman registers of 1525, 1533, 1548, 1553, and 1572.[62] The registers in 1596 recorded the population to consist of 50 Muslim families and 4 bachelors.[63] In 1780, there were about 4,000 inhabitants, two thirds being Jews.[64] In 1842, there were about 3,900 inhabitants, around a third of whom were Jews, the rest being Turks and a few Christians.[65] In 1850, Tiberias contained three synagogues which served the Sephardi community, which consisted of 80 families, and the Ashkenazim, numbering about 100 families. It was reported that the Jewish inhabitants of Tiberias enjoyed more peace and security than those of Safed to the north.[66] In 1863, it was recorded that the Christian and Muslim elements made up three-quarters of the population (2,000 to 4,000).[67] A population list from about 1887 showed that Tiberias had a population of about 3,640; 2,025 Jews, 30 Latins, 215 Catholics, 15 Greek Catholics, and 1,355 Muslims.[68] In 1901, the Jews of Tiberias numbered about 2,000 in a total population of 3,600.[16] By 1912, the population reached 6,500. This included 4,500 Jews, 1,600 Muslims and 400 Christians.[69]

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Tiberias had a population of 6950 inhabitants, consisting of 4,427 Jews, 2,096 Muslims, 422 Christians, and five others.[70] There were 5,381 Jews, 2,645 Muslims, 565 Christians and ten others in the 1931 census.[71] By 1945, the population had increased to 6,000 Jews, 4,540 Muslims, 760 Christians with ten others.[72]

Infrastructure

Urban renewal and preservation

Ancient and medieval Tiberias was destroyed by a series of devastating earthquakes, and much of what was built after the major earthquake of 1837 was destroyed or badly damaged in the great flood of 1934. Houses in the newer parts of town, uphill from the waterfront, survived. In 1949, 606 houses, comprising almost all of the built-up area of the old quarter other than religious buildings, were demolished over the objections of local Jews who owned about half the houses.[73] Wide-scale development began after the Six-Day War, with the construction of a waterfront promenade, open parkland, shopping streets, restaurants and modern hotels. Carefully preserved were several churches, including one with foundations dating from the Crusader period, the city's two Ottoman-era mosques, and several ancient synagogues.[74] The city's old masonry buildings constructed of local black basalt with white limestone windows and trim have been designated historic landmarks. Also preserved are parts of the ancient wall, the Ottoman-era citadel, historic hotels, Christian pilgrim hostels, convents and schools.

Archaeology

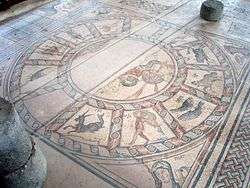

A 2,000 year-old Roman theatre was discovered 15 metres (49 feet) under layers of debris and refuse at the foot of Mount Bernike south of modern Tiberias. It once seated over 7,000 people.[75]

In 2004, excavations in Tiberias conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority uncovered a structure dating to the 3rd century CE that may have been the seat of the Sanhedrin. At the time it was called Beit Hava'ad.[76]

In June 2018, an underground Jewish mausoleum has been discovered. Archaeologist said that the mausoleum is between 1,900 to 2,000 years old as of 2018. The names of the dead, carved onto the ossuaries in Greek.[77]

Geography and climate

Tiberias is located on the shore of the Sea of Galilee and the western slopes of the Jordan Rift Valley overlooking the lake, in the elevation range of −200 to 200 metres (−660–660 feet). Tiberias has a climate that borders a Hot-summer Mediterranean climate (koppen Csa) and a Hot Semi-arid climate (koppen BSh), with an annual precipitation of about 400 mm (15.75 in). Summers in Tiberias average a maximum temperature of 36 °C (97 °F) and a minimum temperature of 21 °C (70 °F) in July and August. The winters are mild, with temperatures ranging from 8 to 18 °C (46–64 °F). Extremes have ranged from 0 °C (32 °F) to 46 °C (115 °F).

| Climate data for Tiberias, Israel (1981–2010 normals), | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 18.1 (64.6) |

19.3 (66.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

27.8 (82) |

33.2 (91.8) |

36.5 (97.7) |

38.0 (100.4) |

38.0 (100.4) |

35.9 (96.6) |

31.6 (88.9) |

25.7 (78.3) |

20.0 (68) |

28.9 (84) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10.4 (50.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.1 (66.4) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.0 (77) |

25.2 (77.4) |

23.3 (73.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.1 (53.8) |

17.66 (63.79) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 106.9 (4.209) |

90.2 (3.551) |

55.5 (2.185) |

17.6 (0.693) |

3.9 (0.154) |

0.1 (0.004) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.6 (0.024) |

17.4 (0.685) |

51.9 (2.043) |

93.0 (3.661) |

437.1 (17.209) |

| Source: WMO (World Weather Information Service)[78] | |||||||||||||

Notes

Earthquakes

Tiberias has been severely damaged by earthquakes since antiquity. Earthquakes are known to have occurred in 30, 33, 115, 306, 363, 419, 447, 631–32 (aftershocks continued for a month), 1033, 1182, 1202, 1546, 1759, 1837, 1927 and 1943.[79]

The city is located above the Dead Sea Transform and is one of the cities in Israel that is most at risk to earthquakes (along with Safed, Beit She'an, Kiryat Shmona, and Eilat).[80]

Sports

Hapoel Tiberias represented the city in the top division of football for several seasons in the 1960s and 1980s, but eventually dropped into the regional leagues and folded due to financial difficulties. Following Hapoel's demise, a new club, Ironi Tiberias, was established, which currently plays in Liga Alef. 6 Nations Championship and Heineken Cup winner Jamie Heaslip was born in Tiberias.

The Tiberias Marathon is an annual road race held along the Sea of Galilee in Israel with a field in recent years of approximately 1000 competitors.The course follows an out-and-back format around the southern tip of the sea, and was run concurrently with a 10k race along an abbreviated version of the same route. In 2010 the 10k race was moved to the afternoon before the marathon. At approximately 200 metres (660 feet) below sea level, this is the lowest course in the world.

Twin towns — sister cities

Tiberias is twinned with:

|

|

Notable residents

List by surname (titles and articles are ignored):

- Yossi Abulafia (born 1944), writer and graphic artist

- Shemariah Catarivas, 18th-century Talmudic writer

- Gadi Eizenkot (born 1960), IDF Chief of General Staff, since Feb. 2015 and still serving as of Oct. 2018

- Menahem Golan (1929–2014), film producer, screenwriter and director

- Jamie Heaslip (born 1983), Irish rugby union player, born in Tiberias

- Rabbi Meir Baal HaNes (Rabbi Meir the miracle maker), 2nd-century CE Jewish sage

- Shlomit Nir (born 1952), Olympic swimmer

- Patrick Denis O'Donnell (1922–2005), Commandant of the Irish Defence Forces, military historian, UN peace-keeper stationed in Tiberias in the 1960s

- Yisroel Ber Odesser (c. 1888–1994), Breslover Hasid and rabbi

- Moshe Peretz (born 1983), Mizrahi pop singer-songwriter and composer

- Eldad Ronen (born 1976), Olympic competitive sailor

- Shem-Tov Sabag (born 1959), Olympic marathoner

- Bechor-Shalom Sheetrit (1895–1967), politician, government minister of Israel

- Zahir al-Umar (1689/90–1775), virtually autonomous Arab ruler of northern Palestine in the mid-18th century

See also

- 1660 destruction of Tiberias

- Bethmaus, ancient Jewish village next to Tiberias

- List of modern names for biblical place names

- Old synagogues of Tiberias

References

- 1 2 "List of localities, in Alphabetical order" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- 1 2 Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.2.3

- ↑ The Sunday at home. Religious Tract Society. 1861. p. 805. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

Tiberias is esteemed a holy city by Israel's children, and has been so dignified ever since the middle of the second century.

- ↑ "PALESTINE, HOLINESS OF - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com.

- 1 2 3 Patricia Erfurt-Cooper; Malcolm Cooper (27 July 2009). Health and Wellness Tourism: Spas and Hot Springs. Channel View Publications. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-84541-363-7.

- 1 2 "TIBERIAS - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com.

- ↑ Joshua 19:35

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Megillah 5b

- ↑ Josephus, Flavius, The Jewish Wars, translated by William Whiston, Book 4, chapter 1, paragraph 3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mercer Dictionary of the Bible Edited by Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard, Mercer University Press, (1998) ISBN 0-86554-373-9 p 917

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Winter, Dave (1999) Israel Handbook: With the Palestinian Authority Areas Footprint Travel Guides, ISBN 1-900949-48-2, pp 660–661

- ↑ Crossan, John Dominic (1999) Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Christ. Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 0-567-08668-2, p 232

- ↑ Thomson, 1859, vol 2, p. 72

- ↑ Safrai Zeev (1994) The Economy of Roman Palestine Routledge, ISBN 0-415-10243-X, p 199

- 1 2 3 Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 3, p. 269

- 1 2 3 "TIBERIAS - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com.

- ↑ Le Strange, 1890, p. 340, quoting Yakut

- 1 2 3 Nir Hasson, 'In excavation of ancient mosque, volunteers dig up Israeli city's Golden Age,' at Haaretz, 17 August 2012.

- ↑ Muk. p.161 and 185, quoted in Le Strange, 1890, pp. 334- 337

- ↑ Le Strange, 1890, pp. 336-7

- ↑ Richard, Jean (1999) The Crusades c. 1071-c 1291, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-62369-3 p 71

- ↑ "Journy of Benjamin of Tudela in Palestine and Syria, c. 1170" in Yaari, p.44

- ↑ Angeliki E. Laiou; Roy P. Mottahedeh (2001). The Crusades from the perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim world. Dumbarton Oaks. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-88402-277-0. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

This hadith is also found in the bibliographical work of the Damascene Ibn ‘Asakir (d. 571/1176), although slightly modified: the four cities of paradise are Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem and Damascus; and the four cities of hell are Constantinople, Tabariyya, Antioch and San'a."

- ↑ Moshe Gil (1997). A history of Palestine, 634–1099. Cambridge University Press. p. 175; ft. 49. ISBN 978-0-521-59984-9. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Wilson, John Francis. (2004) Caesarea Philippi: Banias, the Lost City of Pan I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1-85043-440-9 p 148

- ↑ Yaari, pp.–156

- ↑ Toby Green (2007) Inquisition; The Reign of Fear Macmillan Press ISBN 978-1-4050-8873-2 pp xv–xix

- ↑ Alfassa.com Archived 2007-10-12 at the Wayback Machine. Sephardic Contributions to the Development of the State of Israel, Shelomo Alfassá

- ↑ Schaick, Tzvi. Who is Dona Gracia? Archived 2011-05-10 at the Wayback Machine., The House of Dona Gracia Museum.

- ↑ Naomi E. Pasachoff, Robert J. Littman, A Concise History of the Jewish People, Lanham, Rowman & Littlefield, 2005, p.163

- 1 2 3 Benjamin Lee Gordon, New Judea: Jewish Life in Modern Palestine and Egypt, Manchester, New Hampshire, Ayer Publishing, 1977, p.209

- ↑ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 188

- ↑ "The Druze of the Levant". Archived from the original on 2012-03-09.

- ↑ Joel Rappel, History of Eretz Israel from Prehistory up to 1882 (1980), Vol.2, p.531. 'In 1662 Sabbathai Sevi arrived to Jerusalem. It was the time when the Jewish settlements of Galilee were destroyed by the Druze: Tiberias was completely desolate and only a few of former Safed residents had returned..."

- ↑ Barnay, Y. The Jews in Palestine in the eighteenth century: under the patronage of the Istanbul Committee of Officials for Palestine (University of Alabama Press 1992) ISBN 978-0-8173-0572-7 p. 149

- ↑ Sidney Mendelssohn. The Jews of Asia: especially in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. (1920) p.241. "Long before the culmination of Sabbathai's mad career, Safed had been destroyed by the Arabs and the Jews had suffered severely, while in the same year (1660) there was a great fire in Constantinople in which they endured heavy losses..."

- ↑ Gershom Gerhard Scholem (1976-01-01). Sabbatai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah, 1626–1676. Princeton University Press. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-691-01809-6. "In Safed, too, the [Sabbatai] movement gathered strength during the autumn of 1665. The reports about the utter destruction, in 1662 [sic], of the Jewish settlement there seem greatly exaggerated, and the conclusions based on them are false. ... Rosanes' account of the destruction of the Safed community is based on a misunderstanding of his sources; the community declined in numbers but continued to exist."

- ↑ Pococke, 1745, pp. 68–70

- ↑ Amnon Cohen (1975). Palestine in the 18th Century. Magnes Press. pp. 34–36. ISBN 1-59045-955-5.

- ↑ Moammar, Tawfiq (1990), Zahir Al Omar, Al Hakim Printing Press, Nazareth, p. 70.

- 1 2 3 Joseph Schwarz. Descriptive Geography and Brief Historical Sketch of Palestine, 1850

- ↑ The Jews in Palestine in the eighteenth century: under the patronage of the Istanbul Committee of Officials for Palestine, Y. Barnay, translated by Naomi Goldblum, University of Alabama Press, 1992, p. 15, 16

- ↑ The Jews: their history, culture, and religion, Louis Finkelstein, Edition: 3 Harper, New York, 1960, p. 659

- ↑ Parfitt, Tudor (1987) The Jews in Palestine, 1800–1882. Royal Historical Society studies in history (52). Woodbridge: Published for the Royal Historical Society by Boydell

- ↑ Ashkenazi, Eli (27 December 2009). "Crumbling Tiberias Synagogue to Regain Its Former Glory". www.haaretz.com.

- ↑ Lynch, 1850, p. 154

- ↑ Tiberias – Walking with the sages in Tiberias Archived 2012-01-12 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "MS 38 Torrance Collection". Archive Services Online Catalogue. University of Dundee. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ "The Scots Hotel- History". The Scots Hotel. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ↑ Roxburgh, Angus (2012-10-31). "BBC News – Scots Hotel: Why the Church of Scotland has a Galilee getaway". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ↑ Mandated landscape: British imperial rule in Palestine, 1929–1948, Roza El-Eini, (Routledge, 2006) p. 250

- ↑ The Changing Land: Between the Jordan and the Sea: Aerial Photographs from 1917 to the Present, Benjamin Z. Kedar, Wayne State University Press, 2000, p. 198

- ↑ "United Nations Information System on the Question of Palestine" (.JPG). United Nations Information System on the Question of Palestine. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- 1 2 3 Morris, 2004, pp. 183–185

- ↑ Harry Levin, Jerusalem Embattled – A diary of a city under siege. Cassel, 1997. ISBN 0-304-33765-X., p.81: 'Extraordinary news from Tiberias. The whole Arab population has fled. Last night the Haganah blew up the Arab bands' headquarters there; this morning the Jews woke up to see a panic flight in progress. By tonight not one of the 6,000 Arabs remained.' (19 April).

- ↑ M Gilbert, p. 172

- ↑ Gilbert, p. 245

- ↑ Jeremy Allouche. "The Oriental Communities in Israel 1948-2003". p. 35.

- ↑ M.Gilbert, p.566, 578

- ↑ New ultra-Orthodox neighborhood to be built in Israel's north, Apr. 3, 2012, Haaretz

- ↑ http://www.cbs.gov.il/publications12/local_authorities10/pdf/198_6700.pdf

- ↑ Lewis, Bernard (1954), Studies in the Ottoman archives—I, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 16, pp 469–501.

- ↑ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 188

- ↑ Jolliffe, Thomas Robert 1780-1872 (11 February 2018). "Letters from Palestine, descriptive of a tour through Gallilee and Judaea, with some account of the Dead Sea, and of the present state of Jerusalem". London, J. Black – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ The Penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge: v. 1–27, Volume 23, C. Knight, 1842.

- ↑ M.Gilbert, Israel: A History (1998), p.3

- ↑ Smith, William (1863) A Dictionary of the Bible: Comprising Its Antiquities, Biography, and Natural History Little, Brown, p 149

- ↑ Schumacher, 1888, p. 185

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Tiberias". www.newadvent.org.

- ↑ Barron, 1923, p. 6

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. ?

- ↑ Village Statistics, 1945

- ↑ Arnon Golan, The Politics of Wartime Demolition and Human Landscape Transformation, War in History, vol 9 (2002), pp 431–445.

- ↑ "Old Tiberias synagogue to regain its former glory". www.haaretz.com.

- ↑ 2,000-year-old amphitheater Archived 2009-09-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Ashkenazi, Eli (22 March 2004). "Researchers Say Tiberias Basilica May Have Housed Sanhedrin" – via Haaretz.

- ↑ Builders Accidentally Discover Roman-era Catacomb of Rich Jewish Family in Northern Israel

- ↑ "Tiberias 1981-2010 Climate Normals". World Weather Information Service. Retrieved 2017-05-13.

- ↑ Watzman, Haim (29 May 2007). A Crack in the Earth: A Journey Up Israel's Rift Valley. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0374130589. p. 161.

- ↑ Avraham, Rachel (22 October 2013). "Experts Warn: Major Earthquake Could Hit Israel Any Time". United With Israel.

- ↑ "Choose your family". www.haaretz.com.

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). vol.3: Galilee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Lynch, W.F. (1850). Narrative of the United States' Expedition to the River Jordan and the Dead Sea. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Pococke, R. (1745). A description of the East, and some other countries. 2. London: Printed for the author, by W. Bowyer.

- Pringle, Denys (1997). Secular buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: an archaeological Gazetter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521 46010 7.

- Pringle, Denys (1998). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: L-Z (excluding Tyre). vol.II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 39037 0.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. vol.3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Strange, le, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Thomson, W.M. (1859). The Land and the Book: Or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery, of the Holy Land. 1 (1 ed.). New York: Harper & brothers.

- Thomson, W.M. (1859). The Land and the Book: Or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery, of the Holy Land. 2 (1 ed.). New York: Harper & brothers.

- Yaari, Abraham (1946). מסעות ארץ ישראל: של עולים יהודים מימי הביניים ועד ראשית ימי שיבת ציון: קיבוצם וביאורם - "Eretz Yisrael Journies: of Jewish Pilgrims From The Middle Ages and Until the Beginning of the Return to Zion: Collection and Explanation" (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Gazit. copied and uploaded at "hebrewbooks.org"

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tiberias. |

- the official English Facebook page of Tiberias

- City council website (in Hebrew) Municipality Site in English

- Place To Visit in Tiberias (English)

- Tiberias – City of Treasures: The official website of the Tiberias Excavation Project

- Hamat Tiberias National Park: description, photo gallery

- Nefesh B'Nefesh Community Guide for Tiveria-Tiberias, Israel

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 6: IAA, Wikimedia commons