Umayyad Caliphate

| Umayyad Caliphate ٱلْخِلافَةُ ٱلأُمَوِيَّة | |

|---|---|

| 661–750 | |

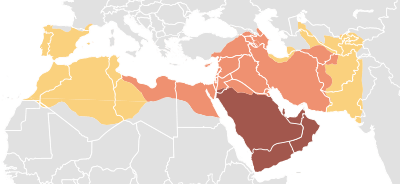

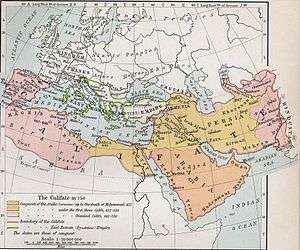

The Umayyad Caliphate at its greatest extent in 750 AD | |

| Capital | |

| Common languages | Classical Arabic (official) – Coptic, Greek, Latin, Persian (official in certain regions until the reign of Abd al-Malik) – Aramaic, Armenian, Berber languages, African Romance, Mozarabic, Sindhi, Georgian, Prakrit |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

| Government | Caliphate |

| Caliph | |

• 661–680 | Muawiya I |

• 680–683 | Yazid I |

• 683-684 | Muawiya II |

| History | |

• Muawiya I becomes Caliph | estimated from 660 to 665 |

| 750 | |

| Area | |

| 720 | 11,100,000[1] km2 (4,300,000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 724 | 33,000,000[2] |

| Currency | Gold dinar and dirham |

| Caliphate خِلافة |

|---|

|

|

Main caliphates |

|

Parallel caliphates |

|

|

| Historical Arab states and dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ancient Arab States

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eastern Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Western Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arabian Peninsula

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Current monarchies

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Umayyad Caliphate (Arabic: ٱلْخِلافَةُ ٱلأُمَوِيَّة, translit. al-Khilāfatu al-ʾUmawiyyah), also spelt Omayyad,[3] was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty (Arabic: ٱلأُمَوِيُّون, al-ʾUmawiyyūn, or بَنُو أُمَيَّة, Banū ʾUmayya, "Sons of Umayya"), hailing from Mecca. The third Caliph, Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656), was a member of the Umayyad clan. The family established dynastic, hereditary rule with Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan, long-time governor of Syria, who became the fifth Caliph after the end of the First Muslim Civil War in 661. After Mu'awiyah's death in 680, conflicts over the succession resulted in a Second Civil War[4] and power eventually fell into the hands of Marwan I from another branch of the clan. Syria remained the Umayyads' main power base thereafter, and Damascus was their capital.

The Umayyads continued the Muslim conquests, incorporating the Transoxiana, Sindh, the Maghreb and the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) into the Muslim world. At its greatest extent, the Umayyad Caliphate covered 11,100,000 km2 (4,300,000 sq mi)[1] and 33 million people,[2] making it one of the largest empires in history in both area and proportion of the world's population. The dynasty was eventually overthrown by a rebellion led by the Abbasids in 750. Survivors of the dynasty established themselves in Cordoba in the form of an Emirate and then a Caliphate, lasting until 1031.

The Umayyad Caliphs were considered too secular by some of their Muslim subjects.[5] Christians, who still constituted a majority of the Caliphate's population, and Jews were allowed to practice their own religion but had to pay a head tax (the jizya) from which Muslims were exempt.[6] There was, however, the smaller Muslim-only zakat tax, which was earmarked explicitly for various welfare progammes.[6][7]

Muawiya's wife Maysum (Yazid's mother) was also a Christian. The relations between the Muslims and the Christians in the state were stable in this time. The Umayyads were involved in frequent battles with the Christian Byzantines without being concerned with protecting themselves in Syria, which had remained largely Christian like many other parts of the empire.[6] Prominent positions were held by Christians, some of whom belonged to families that had served in Byzantine governments. The employment of Christians was part of a broader policy of religious assimilation that was necessitated by the presence of large Christian populations in the conquered provinces, as in Syria. This policy also boosted Muawiya's popularity and solidified Syria as his power base.[8][9]

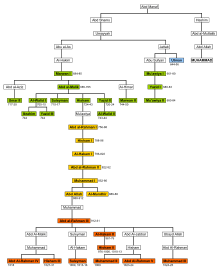

Origins

According to tradition, the Umayyad family (also known as the Banu Abd-Shams) and Muhammad both descended from a common ancestor, Abd Manaf ibn Qusai, and they originally came from the city of Mecca in the Hijaz. Muhammad descended from Abd Manāf via his son Hashim, while the Umayyads descended from Abd Manaf via a different son, Abd-Shams, whose son was Umayya. The two families are therefore considered to be different clans (those of Hashim and of Umayya, respectively) of the same tribe (that of the Quraish).[10]

While the Umayyads felt deep animosity towards the Hashimites before Muhammad (born c. 570 CE), their animosity severely deepened after the Battle of Badr of 624 CE. The battle saw three top leaders of the Umayyad clan (Utba ibn Rabi'ah, Walid ibn Utbah and Shaybah) killed by Hashimites (Ali, Hamza ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib and Ubaydah ibn al-Harith) in a three-on-three melee.[11] This fueled the opposition of Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, the grandson of Umayya, to Muhammad, his family, and Islam as a whole.[12]

Abu Sufyan sought to exterminate the adherents of the new religion by waging another battle against the Medina-based Muslims only a year after the Battle of Badr. He did this to avenge the defeat at Badr. Scholars generally regard the Battle of Uhud (March 625) as the first defeat for the Muslims, since they incurred greater losses than the Meccans. After the battle, Abu Sufyan's wife Hind, who was also the daughter of Utba ibn Rabi'ah, is reported to have cut open the corpse of Hamza, taking out his liver which she then attempted to eat.[12] In 629, however, within five years of the defeat in the Battle of Uhud, Muhammad took control of Mecca[13] and announced a general amnesty for all. Abu Sufyan and his wife Hind embraced Islam on the eve of the conquest of Mecca, as did their son (the future caliph Muawiyah I). However, it has been noted that Muawiya and his family did not become Muslim because of belief in the religion, but rather as a result of the collapse of the pagan society when Mecca was conquered. Banu Umayya had fostered hatred of Islam in their hearts for many years, and they did not suddenly believe in the religion simply because they saw the army of Islam enter Mecca. Rather, it has been noted that Banu Umayya entered the religion of Islam as a "Trojan horse" -- instead of seeking to destroy it as an open enemy, they would seek to destroy the religion from within it.[14]

The Umayyad's ascendancy began when Uthman ibn Affan, who had been an early companian of Muhammad, became the third Caliph. Uthman (644–656) did not establish a dynasty but placed some members of his clan at positions of power.[15] Most notably, he appointed his first cousin, Marwan ibn al-Hakam, as his top advisor, which created a stir among the Hashimite companions of Muhammad, as Marwan (along with his father Al-Hakam ibn Abi al-'As) had been permanently exiled from Medina by Muhammad. Uthman also appointed his half-brother, Walid ibn Uqba, whom Hashimites accused of leading prayer while under the influence of alcohol, governor of Kufa[15] and appointed his foster-brother Abdullah ibn Saad as the Governor of Egypt, replacing Amr ibn al-As.

Most notably, Uthman consolidated Muawiyah's governorship of Syria by granting him control over a larger area.[16] Muawiyah proved a very successful governor. He built up a loyal and disciplined army composed of Syrian Arabs[17] and also befriended Amr ibn al-As, the ousted governor of Egypt. In 639 Muawiyah was appointed as the governor of Syria after the previous governor Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah died in a plague along with 25,000 other people.[18][19] In 649 Muawiyah set up a navy manned by Monophysite Christian, Copt and Jacobite Syrian Christian sailors and Muslim troops, who defeated the Byzantine navy at the Battle of the Masts in 655, opening up the Mediterranean.[20][21][22][23][24]

Uthman's rule also saw the relaxing of restrictions instituted by the second Caliph Umar ibn Al-Khattab. Umar had maintained a tight grip on the governors; if he felt that a governor or a commander was becoming attracted to wealth, he had him removed from his position.[25] Umar also ordered Muslim armies to stay in encampments away from cities because he feared that they might get attracted to wealth and turn away from the worship of God.[25][26][27][28] At the time, tribal differences among Arabs, which had been discouraged in Muhammad's life time,[29][30][31][32][33][34] resurfaced. Deep-rooted differences between Iraq and Syria, that had belonged to the long-warring Sassanid and Byzantine Empire respectively, also persisted.[35]

Conflicts over Uthman's policies led to his murder in 656. Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad, became caliph and moved his capital from Medina to Kufa. He soon met with resistance from several factions, especially from Muawiyah, the governor of Syria, who wanted Uthman's murderers arrested. Muhammad's wife, Aisha, and two companions of Muhammad, Talhah and Al-Zubayr, supported this demand. The conflict resulted in the First Fitna ("civil war") from 656 until 661. Ali was victorious against Aisha in the Battle of the Camel in 656 but the Battle of Siffin (July 657) against Muawiyah was inconclusive. Ali's position als Caliph was weakened when he first agreed to an arbitration but then refused to accept the verdict, that both Ali and Muawiyah should step down and a new Caliph be chosen.[36] In 661, the most vociferous opponents of the arbitration, the Kharijites, tried to kill both rivals; while Ali was killed, the attempt on Muawiyah failed. Ali's son Hasan (the second Imam for the Shias), accepted Muawiyah as Caliph on the condition that he be just to the people and keep them safe and secure, and that he not establish a dynasty to rule after his death.[37][38] In spite of the latter condition, this marked the beginning of the Umayyad dynasty, with its capital in Damascus.[39]

History

Muslim state at the death of Muhammad Expansion under the Rashidun Caliphate Expansion under the Umayyad Caliphate

Sufyanids

Muawiyah's personal dynasty, the "Sufyanids" (descendants of Abu Sufyan), reigned from 661 to 684, until his grandson Muawiya II. The reign of Muawiyah I was marked by internal security and external expansion. On the internal front, only one major rebellion is recorded, that of Hujr ibn Adi in Kufa. Hujr ibn Adi supported the claims of the descendants of Ali to the caliphate, but his movement was easily suppressed by the governor of Iraq, Ziyad ibn Abi Sufyan. Hujr, who had been a sahabah (companion of Muhammad), was sentenced to death by Muawiya for his support of Ali.[40]

Muawiyah also encouraged peaceful coexistence with the Christian communities of Syria, granting his reign with "peace and prosperity for Christians and Arabs alike",[41] and one of his closest advisers was Sarjun, the father of John of Damascus. At the same time, he waged unceasing war against the Byzantine Roman Empire. During his reign, Rhodes and Crete were occupied, and several assaults were launched against Constantinople. After their failure, and faced with a large-scale Christian uprising in the form of the Mardaites, Muawiyah concluded a peace with Byzantium. Muawiyah also oversaw military expansion in North Africa (the foundation of Kairouan) and in Central Asia (the conquest of Kabul, Bukhara, and Samarkand).

Muawiyah was succeeded by his son, Yazid I, in 680. This hereditary accession was opposed by a number of prominent Muslims, most notably Abd-Allah ibn al-Zubayr, son of a companion of Muhammad, and Husayn ibn Ali, the younger son of Ali. The resulting conflict is known as the Second Fitna.[42] Ibn al-Zubayr had fled Medina for Mecca, where he remained in opposition until his death. The people of Kufa invited Husayn to their city and revolt against the Ummayads. However, Yazid I prevented this alliance by having Kufa occupied[43] and Husayn and his family intercepted on their way to Kufa in the Battle of Karbala, in which Husayn and his male family members were killed.[44] Word of Husayn's death fuelled further opposition movements, one centered in Medina and the other around Kharijites in Basra. In 683, Yazid's army suppressed the Medinese opposition at the Battle of al-Harrah and then besieged Mecca. During the campaign, widespread pillaging and the damaging of both the Grand Mosque in Medina and the Kaaba in Mecca caused deep resentment and became a major cause for censure of the Umayyads in later histories of the period.

Yazid died while the siege was still in progress, and the Umayyad army returned to Damascus, leaving Ibn al-Zubayr in control of Mecca. Yazid's son, Muawiya II (683–84), initially succeeded him but seems to have never been recognized as caliph outside of Syria. Two factions developed within Syria: the Confederation of Qays, who supported Ibn al-Zubayr, and the Quda'a, who supported Marwan, a descendant of Umayya via Wa'il ibn Umayyah. The partisans of Marwan triumphed at a battle at Marj Rahit, near Damascus, in 684, and Marwan became Caliph shortly thereafter.

First Marwanids

Marwan's first task was to assert his authority against the rival claims of Ibn al-Zubayr, who was at this time recognized as caliph throughout most of the Islamic world. Marwan recaptured Egypt for the Umayyads, but died in 685, having reigned for only nine months.

Marwan was succeeded by his son, Abd al-Malik (685–705), who reconsolidated Umayyad control of the caliphate. The early reign of Abd al-Malik was marked by the revolt of Al-Mukhtar, which was based in Kufa. Al-Mukhtar hoped to elevate Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah, another son of Ali, to the caliphate, although Ibn al-Hanafiyyah himself may have had no connection to the revolt. The troops of al-Mukhtar engaged in battles both with the Umayyads in 686, defeating them at the river Khazir near Mosul, and with Ibn al-Zubayr in 687, at which time the revolt of al-Mukhtar was crushed. In 691, Umayyad troops reconquered Iraq, and in 692 the same army captured Mecca. Ibn al-Zubayr was killed in the attack.

The second major event of the early reign of Abd al-Malik was the construction of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. Although the chronology remains somewhat uncertain, the building seems to have been completed in 692, which means that it was under construction during the conflict with Ibn al-Zubayr. This had led some historians, both medieval and modern, to suggest that the Dome of the Rock was built as a destination for pilgrimage to rival the Kaaba, which was under the control of Ibn al-Zubayr.

Abd al-Malik is credited with centralizing the administration of the Caliphate and with establishing Arabic as its official language. He also introduced a uniquely Muslim coinage, marked by its aniconic decoration, which supplanted the Byzantine and Sasanian coins that had previously been in use. Abd al-Malik also recommenced offensive warfare against Byzantium, defeating the Byzantines at Sebastopolis and recovering control over Armenia and Caucasian Iberia.

Following Abd al-Malik's death, his son, Al-Walid I (705–15), became caliph. Al-Walid was also active as a builder, sponsoring the construction of Al-Masjid al-Nabawi in Medina and the Great Mosque of Damascus.

In the year 712, Muhammad bin Qasim, an Umayyad general, sailed from the Persian Gulf into Sindh in Pakistan and conquered both the Sindh and the Punjab regions along the Indus river. The conquest of Sindh and Punjab, in modern-day Pakistan, although costly, were major gains for the Umayyad Caliphate. However, further gains were halted by the death of Al-Hajjaj bin Yusuf Al-Thaqafi, as after his death Muhammad was called back from his conquests. After this, Muslim chroniclers admit that the Caliph Mahdi "gave up the project of conquering any part of India".

A major figure during the reigns of both al-Walid and Abd al-Malik was the Umayyad governor of Iraq, Al-Hajjaj bin Yousef. Many Iraqis remained resistant to Umayyad rule, and to maintain order al-Hajjaj imported Syrian troops, which he housed in a new garrison town, Wasit. These troops became crucial in the suppression of a revolt led by an Iraqi general, Ibn al-Ash'ath, in the early eighth century.

Al-Walid was succeeded by his brother, Sulayman (715–17), whose reign was dominated by a protracted siege of Constantinople. The failure of the siege marked the end of serious Arab ambitions against the Byzantine capital. However, the first two decades of the eighth century witnessed the continuing expansion of the Caliphate, which pushed into the Iberian Peninsula in the west, and into Transoxiana in the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana (under Qutayba ibn Muslim) and northern India in the east.

Arab sources claim Qutayba ibn Muslim briefly took Kashgar from China and withdrew after an agreement[45] but modern historians entirely dismiss this claim.[46][47][48]

The Arab Umayyad Caliphate in 715 AD desposed Ikhshid, the king the Fergana Valley, and installed a new king Alutar on the throne. The deposed king fled to Kucha (seat of Anxi Protectorate), and sought Chinese intervention. The Tang dynasty Chinese sent 10,000 troops under Zhang Xiaosong to Ferghana. He defeated Alutar and the Arab occupation force at Namangan and reinstalled Ikhshid on the throne.[49]

The Tang dynasty Chinese defeated the Umayyad invaders at the Battle of Aksu (717). The Arab Umayyad commander Al-Yashkuri and his army fled to Tashkent after they were defeated.[50][51]

Sulayman was succeeded by his cousin, Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz (717–20), whose position among the Umayyad caliphs is somewhat unusual. He is the only Umayyad ruler to have been recognized by subsequent Islamic tradition as a genuine caliph (khalifa) and not merely as a worldly king (malik).

Umar is honored for his attempt to resolve the fiscal problems attendant upon conversion to Islam. During the Umayyad period, the majority of people living within the caliphate were not Muslim, but Christian, Jewish, Zoroastrian, or members of other small groups. These religious communities were not forced to convert to Islam, but were subject to a tax (jizyah) which was not imposed upon Muslims. This situation may actually have made widespread conversion to Islam undesirable from the point of view of state revenue, and there are reports that provincial governors actively discouraged such conversions. It is not clear how Umar attempted to resolve this situation, but the sources portray him as having insisted on like treatment of Arab and non-Arab (mawali) Muslims, and on the removal of obstacles to the conversion of non-Arabs to Islam.

After the death of Umar, another son of Abd al-Malik, Yazid II (720–24) became caliph. Yazid is best known for his "iconoclastic edict", which ordered the destruction of Christian images within the territory of the Caliphate. In 720, another major revolt arose in Iraq, this time led by Yazid ibn al-Muhallab.

Hisham and the limits of military expansion

The final son of Abd al-Malik to become caliph was Hisham (724–43), whose long and eventful reign was above all marked by the curtailment of military expansion. Hisham established his court at Resafa in northern Syria, which was closer to the Byzantine border than Damascus, and resumed hostilities against the Byzantines, which had lapsed following the failure of the last siege of Constantinople. The new campaigns resulted in a number of successful raids into Anatolia, but also in a major defeat (the Battle of Akroinon), and did not lead to any significant territorial expansion.

From the caliphate's north-western African bases, a series of raids on coastal areas of the Visigothic Kingdom paved the way to the permanent occupation of most of Iberia by the Umayyads (starting in 711), and on into south-eastern Gaul (last stronghold at Narbonne in 759). Hisham's reign witnessed the end of expansion in the west, following the defeat of the Arab army by the Franks at the Battle of Tours in 732. In 739 a major Berber Revolt broke out in North Africa, was probably the largest military setback in the reign of Caliph Hisham. From it, emerged some of the first Muslim states outside the Caliphate. It is also regarded as the beginning of Moroccan independence, as Morocco would never again come under the rule of an eastern Caliph or any other foreign power until the 20th century. It was followed by the collapse of Umayyad authority in al-Andalus. In India the Arab armies were defeated by the south Indian Chalukya dynasty and by the north Indian Pratiharas Dynasty in the 8th century and the Arabs were driven out of India.[52][53][54]

In the Caucasus, the confrontation with the Khazars peaked under Hisham: the Arabs established Derbent as a major military base and launched several invasions of the northern Caucasus, but failed to subdue the nomadic Khazars. The conflict was arduous and bloody, and the Arab army even suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Marj Ardabil in 730. Marwan ibn Muhammad, the future Marwan II, finally ended the war in 737 with a massive invasion that is reported to have reached as far as the Volga, but the Khazars remained unsubdued.

Hisham suffered still worse defeats in the east, where his armies attempted to subdue both Tokharistan, with its center at Balkh, and Transoxiana, with its center at Samarkand. Both areas had already been partially conquered, but remained difficult to govern. Once again, a particular difficulty concerned the question of the conversion of non-Arabs, especially the Sogdians of Transoxiana. Following the Umayyad defeat in the "Day of Thirst" in 724, Ashras ibn 'Abd Allah al-Sulami, governor of Khurasan, promised tax relief to those Sogdians who converted to Islam, but went back on his offer when it proved too popular and threatened to reduce tax revenues.

Discontent among the Khurasani Arabs rose sharply after the losses suffered in the Battle of the Defile in 731. In 734, al-Harith ibn Surayj led a revolt that received broad backing from Arabs and natives alike, capturing Balkh but failing to take Merv. After this defeat, al-Harith's movement seems to have been dissolved. The problem of the rights of non-Arab Muslims would continue to plague the Umayyads.

Third Fitna

Hisham was succeeded by Al-Walid II (743–44), the son of Yazid II. Al-Walid is reported to have been more interested in earthly pleasures than in religion, a reputation that may be confirmed by the decoration of the so-called "desert palaces" (including Qusayr Amra and Khirbat al-Mafjar) that have been attributed to him. He quickly attracted the enmity of many, both by executing a number of those who had opposed his accession, and by persecuting the Qadariyya.

In 744, Yazid III, a son of al-Walid I, was proclaimed caliph in Damascus, and his army tracked down and killed al-Walid II. Yazid III has received a certain reputation for piety, and may have been sympathetic to the Qadariyya. He died a mere six months into his reign.

Yazid had appointed his brother, Ibrahim, as his successor, but Marwan II (744–50), the grandson of Marwan I, led an army from the northern frontier and entered Damascus in December 744, where he was proclaimed caliph. Marwan immediately moved the capital north to Harran, in present-day Turkey. A rebellion soon broke out in Syria, perhaps due to resentment over the relocation of the capital, and in 746 Marwan razed the walls of Homs and Damascus in retaliation.

Marwan also faced significant opposition from Kharijites in Iraq and Iran, who put forth first Dahhak ibn Qays and then Abu Dulaf as rival caliphs. In 747, Marwan managed to reestablish control of Iraq, but by this time a more serious threat had arisen in Khorasan.

Abbasid Revolution

The Hashimiyya movement (a sub-sect of the Kaysanites Shia), led by the Abbasid family, overthrew the Umayyad caliphate. The Abbasids were members of the Hashim clan, rivals of the Umayyads, but the word "Hashimiyya" seems to refer specifically to Abu Hashim, a grandson of Ali and son of Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyya. According to certain traditions, Abu Hashim died in 717 in Humeima in the house of Muhammad ibn Ali, the head of the Abbasid family, and before dying named Muhammad ibn Ali as his successor. This tradition allowed the Abbasids to rally the supporters of the failed revolt of Mukhtar, who had represented themselves as the supporters of Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyya.

Beginning around 719, Hashimiyya missions began to seek adherents in Khurasan. Their campaign was framed as one of proselytism (dawah). They sought support for a "member of the family" of Muhammad, without making explicit mention of the Abbasids. These missions met with success both among Arabs and non-Arabs (mawali), although the latter may have played a particularly important role in the growth of the movement.

Around 746, Abu Muslim assumed leadership of the Hashimiyya in Khurasan. In 747, he successfully initiated an open revolt against Umayyad rule, which was carried out under the sign of the black flag. He soon established control of Khurasan, expelling its Umayyad governor, Nasr ibn Sayyar, and dispatched an army westwards. Kufa fell to the Hashimiyya in 749, the last Umayyad stronghold in Iraq, Wasit, was placed under siege, and in November of the same year Abul Abbas as-Saffah was recognized as the new caliph in the mosque at Kufa. At this point Marwan mobilized his troops from Harran and advanced toward Iraq. In January 750 the two forces met in the Battle of the Zab, and the Umayyads were defeated. Damascus fell to the Abbasids in April, and in August, Marwan was killed in Egypt.

The victors desecrated the tombs of the Umayyads in Syria, sparing only that of Umar II, and most of the remaining members of the Umayyad family were tracked down and killed. When Abbasids declared amnesty for members of the Umayyad family, eighty gathered to receive pardons, and all were massacred. One grandson of Hisham, Abd al-Rahman I, survived, escaped across North Africa, and established an emirate in Moorish Iberia (Al-Andalus). In a claim unrecognized outside of al-Andalus, he maintained that the Umayyad Caliphate, the true, authentic caliphate, more legitimate than the Abbasids, was continued through him in Córdoba. It was to survive for centuries.

Previté-Orton argues that the reasons for the decline of the Umayyads was the rapid expansion of Islam. During Umayyad period, mass conversions brought Persians, Berbers, Copts, and Aramaics to Islam. These mawalis (enslaved) were often better educated and more civilised than their Arab invaders. The new converts, on the basis of equality of all Muslims, transformed the political landscape. Previté-Orton also argues that the feud between Syria and Iraq further weakened the empire.[55]

Umayyad administration

The first four caliphs created a stable administration for the empire, following the practices and administrative institutions of the Byzantine Empire which had ruled the same region previously.[56] These consisted of four main governmental branches: political affairs, military affairs, tax collection, and religious administration. Each of these was further subdivided into more branches, offices, and departments.

Provinces

Geographically, the empire was divided into several provinces, the borders of which changed numerous times during the Umayyad reign. Each province had a governor appointed by the khalifah. The governor was in charge of the religious officials, army leaders, police, and civil administrators in his province. Local expenses were paid for by taxes coming from that province, with the remainder each year being sent to the central government in Damascus. As the central power of the Umayyad rulers waned in the later years of the dynasty, some governors neglected to send the extra tax revenue to Damascus and created great personal fortunes.[57]

Government workers

As the empire grew, the number of qualified Arab workers was too small to keep up with the rapid expansion of the empire. Therefore, Muawiya allowed many of the local government workers in conquered provinces to keep their jobs under the new Umayyad government. Thus, much of the local government's work was recorded in Greek, Coptic, and Persian. It was only during the reign of Abd al-Malik that government work began to be regularly recorded in Arabic.[57]

Currency

The Byzantine and Sassanid Empires relied on money economies before the Muslim conquest, and that system remained in effect during the Umayyad period. Byzantine copper coins were used until 658, while Byzantine gold coins were still in use until the monetary reforms c.700.[58] In addition to this, the Umayyad government began to mint its own coins in Damascus, these were initially similar to pre-existing coins but evolved in an independent direction. These were the first coins minted by a Muslim government in history. Gold coins were called dinars while silver coins were called dirhams.[57]

Central diwans

To assist the Caliph in administration there were six Boards at the Centre: Diwan al-Kharaj (the Board of Revenue), Diwan al-Rasa'il (the Board of Correspondence), Diwan al-Khatam (the Board of Signet), Diwan al-Barid (the Board of Posts), Diwan al-Qudat (the Board of Justice) and Diwan al-Jund (the Military Board)

Diwan al-Kharaj

The Central Board of Revenue administered the entire finances of the empire. It also imposed and collected taxes and disbursed revenue.

Diwan al-Rasa'il

A regular Board of Correspondence was established under the Umayyads. It issued state missives and circulars to the Central and Provincial Officers. It co-ordinated the work of all Boards and dealt with all correspondence as the chief secretariat.

Diwan al-Khatam

In order to check forgery, Diwan al-Khatam (Bureau of Registry), a kind of state chancellery, was instituted by Mu'awiyah. It used to make and preserve a copy of each official document before sealing and despatching the original to its destination. Thus in the course of time a state archive developed in Damascus by the Umayyads under Abd al-Malik. This department survived till the middle of the Abbasid period.

Diwan al-Barid

Mu'awiyah introduced postal service, Abd al-Malik extended it throughout his empire, and Walid made full use of it. The Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik developed a regular postal service. Umar bin Abdul-Aziz developed it further by building caravanserais at stages along the Khurasan highway. Relays of horses were used for the conveyance of dispatches between the caliph and his agents and officials posted in the provinces. The main highways were divided into stages of 12 miles (19 km) each and each stage had horses, donkeys or camels ready to carry the post. Primarily the service met the needs of Government officials, but travellers and their important dispatches were also benefitted by the system. The postal carriages were also used for the swift transport of troops. They were able to carry fifty to a hundred men at a time. Under Governor Yusuf bin Umar, the postal department of Iraq cost 4,000,000 dirhams a year.

Diwan al-Qudat

In the early period of Islam, justice was administered by Muhammad and the orthodox Caliphs in person. After the expansion of the Islamic State, Umar al-Faruq had to separate judiciary from the general administration and appointed the first qadi in Egypt as early as AD 643/23 AH. After 661, a series of judges succeeded one after another in Egypt under the Umayyad Caliphs, Hisham and Walid II.

Diwan al-Jund

The Diwan of Umar, assigning annuities to all Arabs and to the Muslim soldiers of other races, underwent a change in the hands of the Umayyads. The Umayyads meddled with the register and the recipients regarded pensions as the subsistence allowance even without being in active service. Hisham reformed it and paid only to those who participated in battle. On the pattern of the Byzantine system the Umayyads reformed their army organization in general and divided it into five corps: the centre, two wings, vanguards and rearguards, following the same formation while on march or on a battle field. Marwan II (740–50) abandoned the old division and introduced Kurdus (cohort), a small compact body. The Umayyad troops were divided into three divisions: infantry, cavalry and artillery. Arab troops were dressed and armed in Greek fashion. The Umayyad cavalry used plain and round saddles. The artillery used arradah (ballista), manjaniq (the mangonel) and dabbabah or kabsh (the battering ram). The heavy engines, siege machines and baggage were carried on camels behind the army.

Social organization

The Umayyad Caliphate exhibited four main social classes:

- Muslim Arabs

- Muslim non-Arabs (clients of the Muslim Arabs)

- Dhimmis, non-Muslim free persons (Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, and others)

- Slaves

The Muslim Arabs were at the top of the society and saw it as their duty to rule over the conquered areas. Despite the fact that Islam teaches the equality of all Muslims, the Arab Muslims held themselves in higher esteem than Muslim non-Arabs and generally did not mix with other Muslims.

The inequality of Muslims in the empire led to social unrest. As Islam spread, more and more of the Muslim population was constituted of non-Arabs. This caused tension as the new converts were not given the same rights as Muslim Arabs. Also, as conversions increased, tax revenues from non-Muslims decreased to dangerous lows. These issues continued to grow until they helped cause the Abbasid Revolt in the 740s.[60]

Non-Muslims

Non-Muslim groups in the Umayyad Caliphate, which included Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, and pagan Berbers, were called dhimmis. They were given a legally protected status as second-class citizens as long as they accepted and acknowledged the political supremacy of the ruling Muslims, i.e. paid a tax, known as jizya, which the Muslims did not have to pay, who would instead pay the zakat tax. If they converted to Islam they would cease paying jizya and would instead pay zakat. They were allowed to have their own courts, and were given freedom of their religion within the empire. Although they could not hold the highest public offices in the empire, they had many bureaucratic positions within the government. Christians and Jews still continued to produce great theological thinkers within their communities, but as time wore on, many of the intellectuals converted to Islam, leading to a lack of great thinkers in the non-Muslim communities.[61]

Legacy

Currently many Sunni scholars agree that Muawiyah I's family, including his progenitors, Abu Sufyan ibn Harb and Hind bint Utbah, were originally opponents of Islam and particularly of Muhammad until the Conquest of Mecca.

However many early history books like the Islamic Conquest of Syria Fatuhusham by al-Imam al-Waqidi state that after the conversion to Islam Muawiyah I's father Abu Sufyan ibn Harb and his brothers Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan were appointed as commanders in the Muslim armies by Muhammad. Muawiyah I, Abu Sufyan ibn Harb, Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan and Hind bint Utbah[62][63][63][64][65][66] fought in the Battle of Yarmouk. The defeat of the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius at the Battle of Yarmouk opened the way for the Muslim expansion into Jerusalem and Syria.

In 639, Muawiyah was appointed as the governor of Syria by the second caliph Umar after his brother the previous governor Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan and the governor before him Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah died in a plague along with 25,000 other people.[67][68] 'Amr ibn al-'As was sent to take on the Roman Army in Egypt. Fearing an attack by the Romans, Umar asked Muawiyah to defend against a Roman attack.

With limited resources Muawiyah went about creating allies. Muawiyah married Maysum the daughter of the chief of the Kalb tribe, that was a large Jacobite Christian Arab tribe in Syria. His marriage to Maysum was politically motivated. The Kalb tribe had remained largely neutral when the Muslims first went into Syria.[69] After the plague that killed much of the Muslim Army in Syria, by marrying Maysum, Muawiyah started to use the Jacobite Christians, against the Romans. Muawiya's wife Maysum (Yazid's mother) was also a Jacobite Christian.[70] With limited resources and the Byzantine just over the border, Muawiyah worked in cooperation with the local Christian population. To stop Byzantine harassment from the sea during the Arab-Byzantine Wars, in 649 Muawiyah set up a navy; manned by Monophysitise Christians, Copts and Jacobite Syrian Christians sailors and Muslim troops.[71][72]

Muawiya was one of the first to realize the full importance of having a navy; as long as the Byzantine fleet could sail the Mediterranean unopposed, the coast line of Syria, Palestine and Egypt would never be safe. Muawiyah along with Adbullah ibn Sa'd the new governor of Egypt successfully persuaded Uthman to give them permission to construct a large fleet in the dockyards of Egypt and Syria[71][72]

The first real naval engagement between the Muslim and the Byzantine navy was the so-called Battle of the Masts (Dhat al-sawari) or battle of Phoenix off the Lycian coast in 655.[73] This resulted in the defeat of the Byzantine navy at the Battle of the Masts in 655, opening up the Mediterranean.[71][72][74][75][76][77][78]

Muawiyah I came to power after the death of Ali and established a dynasty.

Historical significance

| History of the Levant |

|---|

| Stone Age |

| Ancient history |

| Classical antiquity |

| Middle Ages |

| Modern history |

The Umayyad caliphate was marked both by territorial expansion and by the administrative and cultural problems that such expansion created. Despite some notable exceptions, the Umayyads tended to favor the rights of the old Arab families, and in particular their own, over those of newly converted Muslims (mawali). Therefore, they held to a less universalist conception of Islam than did many of their rivals. As G.R. Hawting has written, "Islam was in fact regarded as the property of the conquering aristocracy."[79]

During the period of the Umayyads, Arabic became the administrative language. State documents and currency were issued in the language. Mass conversions brought a large influx of Muslims to the caliphate. The Umayyads also constructed famous buildings such as the Dome of the Rock at Jerusalem, and the Umayyad Mosque at Damascus.[80]

According to one common view, the Umayyads transformed the caliphate from a religious institution (during the rashidun) to a dynastic one.[80] However, the Umayyad caliphs do seem to have understood themselves as the representatives of God on earth, and to have been responsible for the "definition and elaboration of God's ordinances, or in other words the definition or elaboration of Islamic law."[81]

The Umayyads have met with a largely negative reception from later Islamic historians, who have accused them of promoting a kingship (mulk, a term with connotations of tyranny) instead of a true caliphate (khilafa). In this respect it is notable that the Umayyad caliphs referred to themselves not as khalifat rasul Allah ("successor of the messenger of God", the title preferred by the tradition), but rather as khalifat Allah ("deputy of God"). The distinction seems to indicate that the Umayyads "regarded themselves as God's representatives at the head of the community and saw no need to share their religious power with, or delegate it to, the emergent class of religious scholars."[82] In fact, it was precisely this class of scholars, based largely in Iraq, that was responsible for collecting and recording the traditions that form the primary source material for the history of the Umayyad period. In reconstructing this history, therefore, it is necessary to rely mainly on sources, such as the histories of Tabari and Baladhuri, that were written in the Abbasid court at Baghdad.

Modern Arab nationalism regards the period of the Umayyads as part of the Arab Golden Age which it sought to emulate and restore. This is particularly true of Syrian nationalists and the present-day state of Syria, centered like that of the Umayyads on Damascus.

The Umayyad dynastic color was white, after the banner of Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan;[83] it is now one of the four Pan-Arab colors which appear in various combinations on the flags of most Arab countries.

Theological opinions concerning the Umayyads

Sunni opinions

Many Muslims criticized the Umayyads for having too many non-Muslim, former Roman administrators in their government. St John of Damascus was also a high administrator in the Umayyad administration.[84] As the Muslims took over cities, they left the peoples political representatives and the Roman tax collectors and the administrators. The taxes to the central government were calculated and negotiated by the peoples political representatives. The Central government got paid for the services it provided and the local government got the money for the services it provided. Many Christian cities also used some of the taxes on maintain their churches and run their own organizations. Later the Umayyads were criticized by some Muslims for not reducing the taxes of the people who converted to Islam. These new converts continued to pay the same taxes that were previously negotiated.[85]

Later when Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz came to power, he reduced these taxes. He is therefore praised as one of the greatest Muslim rulers after the four Rightly Guided Caliphs. Imam Abu Muhammad Adbullah ibn Abdul Hakam who lived in 829 and wrote a biography on Umar Ibn Adbul Aziz[86] stated that the reduction in these taxes stimulated the economy and created wealth but it also reduced the government budget and this then led to a reduction in the defense budget.

Only Umayyad ruler (Caliphs of Damascus), Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz, is unanimously praised by Sunni sources for his devout piety and justice. In his efforts to spread Islam he established liberties for the Mawali by abolishing the jizya tax for converts to Islam. Imam Abu Muhammad Adbullah ibn Abdul Hakam stated that Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz also stopped the personal allowance offered to his relatives stating that he could only give them an allowance if he gave an allowance to everyone else in the empire. Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz was later poisoned in the year 720. When successive governments tried to reverse Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz's tax policies it created rebellion.

Shi'a opinions

The negative view of the Umayyads by Shias is briefly expressed in the Shi'a book "Sulh al-Hasan".[87] According to Shia hadiths, which are not considered authentic by Sunnis, Ali described them as the worst Fitna.[88] In Shia sources, the Umayyad Caliphate is widely described as "tyrannical, anti-Islamic and godless".[89][90] Shias point out that the founder of the dynasty, Muawiyah, declared himself a caliph in 657 and went to war against Muhammad's son-in-law, ruling Rashidun caliph Ali, clashing at the Battle of Siffin. Muawiyah also declared his son, Yazid, as a successor in breach of a treaty with Hassan, Muhammad's grandson. Another of Muhammad's grandsons, Husayn ibn Ali, would be killed by Yazid in the Battle of Karbala. Further Shia Imams, such as Muhammad's great-grandson, Ali ibn Husayn Zayn al-Abidin would be killed at the hands of ruling Umayyad caliphs.

Early literature

The book Al Muwatta by Imam Malik was written in the early Abbasid period in Madina. It does not contain any anti-Umayyad content because it was more concerned with what the Quran and what Muhammad said and was not a history book on the Umayyads.

Even the earliest pro-Shia accounts of al-Masudi are more balanced. al-Masudi in Ibn Hisham is the earliest Shia account of Muawiyah. He recounted that Muawiyah spent a great deal of time in prayer, in spite of the burden of managing a large empire.[91]

Az-Zuhri stated that Muawiya led the Hajj Pilgrimage with the people twice during his era as caliph.

Books written in the early Abbasid period like al-Baladhuri's "The Origins of the Islamic State" provide a more accurate and balanced history. Ibn Hisham also wrote about these events.

Much of the anti-Umayyad literature started to appear in the later Abbasid period in Persia.

After killing off most of the Umayyads and destroying the graves of the Umayyad rulers apart from Muawiyah and Umar Ibn Adbul Aziz, the history books written during the later Abbasid period are more anti-Umayyad.[92] The Abbasids justified their rule by saying that their ancestor Abbas ibn Abd al Muttalib was a cousin of Muhammad.

The books written later in the Abbasid period in Iran are more anti-Umayyad. Iran was Sunni at the time. There was much anti-Arab feeling in Iran after the fall of the Persian empire.[93] This anti-Arab feeling also influenced the books on Islamic history. Al-Tabri was also written in Iran during that period. Al-Tabri was a huge collection including all the texts that he could find, from all the sources. It was a collection preserving everything for future generations to codify and for future generations to judge whether the histories were true or false.

Bahá'í standpoint

Asked for an explanation of the prophecies in the Book of Revelation (12:3), `Abdu'l-Bahá suggests in Some Answered Questions that the "great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads,"[94] refers to the Umayyad caliphs who "rose against the religion of Prophet Muhammad and against the reality of Ali".[95][96]

The seven heads of the dragon is symbolic of the seven provinces of the lands dominated by the Umayyads: Damascus, Persia, Arabia, Egypt, Africa, Andalusia, and Transoxania. The ten horns represent the ten names of the leaders of the Umayyad dynasty; Abu Sufyan, Muawiya, Yazid, Marwan, Abd al-Malik, Walid, Sulayman, Umar, Hisham, and Ibrahim. Some names were re-used, as in the case of Yazid II and Yazid III, which were not counted for this interpretation.

List of Caliphs

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Iran | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Related articles |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Afghanistan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ancient

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Associated Historical Regions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Greater Iran | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pre-Islamic BCE / BC

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Caliph | Reign |

|---|---|

| Caliphs of Damascus | |

| Muawiya I ibn Abu Sufyan | 28 July 661 – 27 April 680 |

| Yazid I ibn Muawiyah | 27 April 680 – 11 November 683 |

| Muawiya II ibn Yazid | 11 November 683– June 684 |

| Marwan I ibn al-Hakam | June 684– 12 April 685 |

| Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan | 12 April 685 – 8 October 705 |

| al-Walid I ibn Abd al-Malik | 8 October 705 – 23 February 715 |

| Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik | 23 February 715 – 22 September 717 |

| Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz | 22 September 717 – 4 February 720 |

| Yazid II ibn Abd al-Malik | 4 February 720 – 26 January 724 |

| Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik | 26 January 724 – 6 February 743 |

| al-Walid II ibn Yazid | 6 February 743 – 17 April 744 |

| Yazid III ibn al-Walid | 17 April 744 – 4 October 744 |

| Ibrahim ibn al-Walid | 4 October 744 – 4 December 744 |

| Marwan II ibn Muhammad (ruled from Harran in the Jazira) | 4 December 744 – 25 January 750 |

| Emirs of Cordoba | |

| Abd al-Rahman I | 756–788 |

| Hisham I | 788–796 |

| al-Hakam I | 796–822 |

| Abd ar-Rahman II | 822–852 |

| Muhammad I | 852–886 |

| Al-Mundhir | 886–888 |

| Abdallah ibn Muhammad | 888–912 |

| Abd ar-Rahman III | 912–929 |

| Caliphs of Cordoba | |

| Abd ar-Rahman III, as caliph | 929–961 |

| Al-Hakam II | 961–976 |

| Hisham II | 976–1008 |

| Muhammad II | 1008–1009 |

| Sulayman ibn al-Hakam | 1009–1010 |

| Hisham II, restored | 1010–1012 |

| Sulayman ibn al-Hakam, restored | 1012–1017 |

| al-Mu'ayti, rival in Denia | 1014–1016 |

| Abd ar-Rahman IV | 1021–1022 |

| Abd ar-Rahman V | 1022–1023 |

| Muhammad III | 1023–1024 |

| Hisham III | 1027–1031 |

See also

References

- 1 2 Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 496. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793.

- 1 2 Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994), The End of the Jihad State, the Reign of Hisham Ibn 'Abd-al Malik and the collapse of the Umayyads, State University of New York Press, p. 37, ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7

- ↑ "Umayyad dynasty". Britannica. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ Bukhari, Sahih. "Sahih Bukhari: Read, Study, Search Online".

- ↑ "Umayyad dynasty | Islamic history". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- 1 2 3 H.U. Rahman , A Chronology Of Islamic History 570-1000 CE (1999), p. 128.

- ↑ "Islamic Economics". www.hetwebsite.net.

- ↑ Cavendish, Marshall (1 September 2006). World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9780761475712 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Haag, Michael (1 November 2012). The Tragedy of the Templars: The Rise and Fall of the Crusader States. Profile Books. ISBN 9781847658548 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Muslim Congress". Archived from the original on 2008-02-24. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ↑ "Partial Translation of Sunan Abu-Dawud, Book 14: Jihad (Kitab Al-Jihad): Number 2659". University of Southern California. Archived from the original on 18 August 2000.

- 1 2 Ibn Ishaq (1955) 380—388, cited in Peters (1994) p. 218

- ↑ Watt (1956), p. 66

- ↑ Razwy, Sayed Ali Asgher. A Restatement of the History of Islam & Muslims. pp. 229–231.

- 1 2 Ibn Taymiya, in his A Great Compilation of Fatwa

- ↑ Ibn Kathir: Al-Bidayah wal-Nihayah, Volume 8 page 164

- ↑ A Short History of Islam: From the Rise of Islam to the Fall of Baghdad - p. 412.

- ↑ Wilferd Madelung, The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate, p.61

- ↑ Rahman (1999, p. 40)

- ↑ Lewis, Archibald Ross; Runyan, Timothy J. (1 January 1990). European Naval and Maritime History, 300-1500. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253205735 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Leonard Michael Kroll, History of the Jihad, page 123

- ↑ Jim Bradbury, The Medieval Siege, A History of Byzantium By Timothy E. Gregory page 183

- ↑ Weston, Mark (28 July 2008). Prophets and Princes: Saudi Arabia from Muhammad to the Present. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470182574 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Bradbury, Jim (1 January 1992). The Medieval Siege. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9780851153575 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 Sami Ayad Hanna; George H. Gardner, eds. (1969). "Early Statements on Ishtirakiyyah". Arab Socialism. [al-Ishtirakīyah Al-ʻArabīyah]: A Documentary Survey. E. J. Brill. p. 271. GGKEY:EDBBNXAKPQ2. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ↑ Khālid, Khālid Muḥammad (5 March 2017). Men Around the Messenger. The Other Press. ISBN 9789839154733 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Holt, P. M.; Holt, Peter Malcolm; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (21 April 1977). The Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 2B, Islamic Society and Civilisation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521291385 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Ali, Maulana Muhammad; Jeff, Mitch Creekmore (9 August 2011). The Early Caliphate. Ahmadiyya Anjuman Ishaat Islam Lahore USA. ISBN 9781934271254 – via Google Books.

- ↑ The Spread of Islam: The Contributing Factors By Abu al-Fazl Izzati, A. Ezzati Page 301

- ↑ Islam For Dummies By Malcolm Clark Page

- ↑ Spiritual Clarity By Jackie Wellman Page 51

- ↑ Quran: The Surah Al-Nisa, Ch4:v2

- ↑ Quran: Surat Al-Hujurat [49:13]

- ↑ Quran: Surat An-Nisa' [4:1]

- ↑ Iraq a Complicated State: Iraq's Freedom War By Karim M. S. Al-Zubaidi Page 32

- ↑ A Chronology of Islamic History 570-1000 CE By H U Rahman Page 59

- ↑ Madelung, Wilferd (15 October 1998). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521646963 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Bukhari, Sahih. "Sahih Bukhari: Book of "Peacemaking"".

- ↑ Holt (1977a, pp. 67–72)

- ↑ Nakshawani, Sayed Ammar. Hujr Ibn Adi: A Victim of Terror. Sun Behind the Cloud Publications.

- ↑ R h o d e s, Bryan. JOHN DAMASCENE IN CONTEXT An Examination of "The Heresy of the Ishmaelites" with special consideration given to the Religious, Political, and Social Contexts during the Seventh and Eighth Century Arab Conquests (PDF). p. 105. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-17.

- ↑ Bukhari, Sahih. "Sahih Bukhari: Read, Study, Search Online".

- ↑ Kitab Al-Irshad by Historian Sheikh Mufid

- ↑ Kitab Al-Irshad by Historian Sheikh Mufid

- ↑ Muhamad S. Olimat (27 August 2015). China and Central Asia in the Post-Soviet Era: A Bilateral Approach. Lexington Books. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-1-4985-1805-5.

- ↑ Litvinsky, B. A.; Jalilov, A. H.; Kolesnikov, A. I. (1996). "The Arab Conquest". In Litvinsky, B. A. History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III: The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. pp. 449–472. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- ↑ Bosworth, C. E. (1986). "Ḳutayba b. Muslim". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 541–542. ISBN 90-04-07819-3.

- ↑ Gibb, H. A. R. (1923). The Arab Conquests in Central Asia. London: The Royal Asiatic Society. pp. 48–51. OCLC 685253133.

- ↑

- Bai, Shouyi et al. (2003). A History of Chinese Muslim (Vol.2). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. ISBN 7-101-02890-X., pp. 235-236

- ↑ Christopher I. Beckwith (28 March 1993). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power Among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese During the Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-691-02469-1.

- ↑ Insight Guides (1 April 2017). Insight Guides Silk Road. APA. ISBN 978-1-78671-699-6.

- ↑ The Cambridge Shorter History of India p.131-132

- ↑ Early India: From the Origins to A.D. 1300 by Romila Thapar p.333

- ↑ An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History by Karl J. Schmidt p.34

- ↑ Previté-Orton (1971), vol. 1, pg. 239

- ↑ Neal Robinson, Islam: A Concise Introduction, (RoutledgeCurzon, 1999), 22.

- 1 2 3 Ochsenwald, William (2004). The Middle East, A History. McGraw Hill. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-07-244233-5.

- ↑ The Mining, Minting, and Acquisition of Gold in the Roman and Post-Roman World, Fernando Lopez Sanchez, Ownership and Exploitation of Land and Natural Resources in the Roman World, ed. Paul Erdkamp, Koenraad Verboven, and Arjan Zuiderhoek, (Oxford University Press, 2015), 324.

- ↑ R.M. Foote et al., Report on Humeima excavations, in V. Egan and P.M. Bikai, "Archaeology in Jordan", American Journal of Archaeology 103 (1999), p. 514.

- ↑ Ochsenwald, William (2004). The Middle East, A History. McGraw Hill. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-07-244233-5.

- ↑ Ochsenwald, William (2004). The Middle East, A History. McGraw Hill. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-07-244233-5.

- ↑ Islamic Conquest of Syria A translation of Fatuhusham by al-Imam al-Waqidi Translated by Mawlana Sulayman al-Kindi, page 325 Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 al-Baladhuri 892 [19] Medieval Sourcebook: Al-Baladhuri: The Battle Of The Yarmuk (636) Archived 11 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Islamic Conquest of Syria A translation of Fatuhusham by al-Imam al-Waqidi Translated by Mawlana Sulayman al-Kindi, page 331 to 334 Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Islamic Conquest of Syria A translation of Fatuhusham by al-Imam al-Waqidi Translated by Mawlana Sulayman al-Kindi, page 343-344 Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ al-Baladhuri 892 [20] from The Origins of the Islamic State, being a translation from the Arabic of the Kitab Futuh al-Buldha of Ahmad ibn-Jabir al-Baladhuri, trans. by P. K. Hitti and F. C. Murgotten, Studies in History, Economics and Public Law, LXVIII (New York, Columbia University Press, 1916 and 1924), I, 207-211

- ↑ Madelung, Wilferd (1998). The Succession to Muhammad A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64696-3.

- ↑ A Chronology Of Islamic History 570-1000 CE, By H.U. Rahman 1999 Page 40

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Islam Volume VII, page 265, By Bosworth

- ↑ A Chronology Of Islamic History 570-1000 CE, By H.U. Rahman 1999 Page 72

- 1 2 3 A Chronology Of Islamic History 570-1000 CE, By H.U. Rahman 1999 Page 48-49

- 1 2 3 The Great Arab Conquests By Hugh Kennedy, page 326

- ↑ The Great Arab Conquests By Hugh Kennedy, page 327

- ↑ Lewis, Archibald Ross (1985). European Naval and Maritime History, 300-1500. Indiana University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-253-32082-7.

- ↑ Kroll, Leonard Michael (2005). History of the Jihad Islam Versus Civilization. AuthorHouse. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-4634-5730-3.

- ↑ Gregory, Timothy E. (2011). A History of Byzantium. John Wiley & Sons. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-4443-5997-8.

- ↑ Weston, Mark (2008). Prophets and Princes Saudi Arabia from Muhammad to the Present. John Wiley & Sons. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-470-18257-4.

- ↑ Bradbury, Jim (1992). The Medieval Siege. Boydell & Brewer. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-85115-357-5.

- ↑ G.R. Hawting, The first dynasty of Islam: the Umayyad caliphate, AD 661–750 (London, 2000), 4.

- 1 2 Previté-Orton (1971), pg 236

- ↑ P. Crone and M. Hinds, God's caliph: religious authority in the first centuries of Islam (Cambridge, 1986), p. 43.

- ↑ G.R. Hawting, The first dynasty of Islam: the Umayyad caliphate, AD 661–750 (London, 2000), 13.

- ↑ Hathaway, Jane (2012). A Tale of Two Factions: Myth, Memory, and Identity in Ottoman Egypt and Yemen. SUNY Press. p. 97. ISBN 9780791486108.

- ↑ Choueiri, Youssef M. (15 April 2008). A Companion to the History of the Middle East. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781405152044 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Student Resources, Chapter 12: The First Global Civilization: The Rise and Spread of Islam, IV. The Arab Empire of the Umayyads, G. Converts and 'People of the Book'". occawlonline.pearsoned.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2002.

- ↑ Umar Ibn Adbul Aziz By Imam Abu Muhammad Adbullah ibn Abdul Hakam died 214 AH 829 C.E. Publisher Zam Zam Publishers Karachi

- ↑ Shaykh Radi Aal-yasin (2000). "Mu'awiya And The Shi'a Of 'Ali, Peace Be On Him". Sulh Al-Hasan. Ansariyan Publishers. pp. 297–344. ISBN 978-1-4960-4085-5. Archived from the original on 20 January 2004.

- ↑ "Sermon 92: About the annihilation of the Kharijites, the mischief mongering of Umayyads and the vastness of his own knowledge". nahjulbalagha.org. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007.

- ↑ Sharon, Moshe (1983). Black Banners from the East: The Establishment of the ʻAbbāsid State : Incubation of a Revolt. JSAI. ISBN 9789652235015.

- ↑ Khan, M. A. (2009-01-29). Islamic Jihad: A Legacy of Forced Conversion, Imperialism, and Slavery. iUniverse. ISBN 9781440118487.

- ↑ Muawiya Restorer of the Muslim Faith By Aisha Bewley Page 41

- ↑ McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (2006). The Cambridge Companion to the Qur'an. Cambridge University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-521-53934-0.

- ↑ Badiozamani, Badi; Badiozamani, Ghazal (2005). Iran and America Re-Kind[l]ing a Love Lost. East West Understanding Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-9742172-0-8.

- ↑ "Bible". biblegateway.com. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ↑ `Abdu'l-Bahá (1990) [1908]. Some Answered Questions. Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá'í Publishing Trust,. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-87743-190-9.

- ↑ `Abdu'l-Bahá (1990) [1908]. Some Answered Questions. Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá'í Publishing Trust,. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-87743-190-9.

Further reading

- AL-Ajmi, Abdulhadi, The Umayyads, in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God (2 vols.), Edited by C. Fitzpatrick and A. Walker, Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 2014. ISBN 1610691776

- A. Bewley, Mu'awiya, Restorer of the Muslim Faith (London, 2002)

- Boekhoff-van der Voort, Nicolet, Umayyad Court, in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God (2 vols.), Edited by C. Fitzpatrick and A. Walker, Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 2014. ISBN 1610691776

- P. Crone, Slaves on horses (Cambridge, 1980).

- P. Crone and M.A. Cook, Hagarism (Cambridge, 1977).

- F. M. Donner, The early Islamic conquests (Princeton, 1981).

- G. R. Hawting, The first dynasty of Islam: the Umayyad caliphate, AD 661–750 Rutledge Eds. (London, 2000)

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Previté-Orton, C. W (1971). The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- J. Wellhausen, The Arab Kingdom and its fall (London, 2000).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Umayyads. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Ommiads. |

- Umayyads

- Umayyads – First caliphate dynasty

- Timeline of Islamic caliphs by Happy Books

- Interactive Family tree of Umayyah ibn Abd Shams by Happy Books

— Imperial house — Cadet branch of the Quraysh | ||

| Vacant | Caliphate dynasty 661 – 6 August 750 |

Succeeded by Abbasid dynasty |

| Preceded by Umayyad dynasty as Caliph |

Ruling house of Emirate of Córdoba 15 May 756 – 16 January 929 |

Emirate Elevated Proclaimed as Caliphate |

| New title |

Ruling house of Caliphate of Córdoba 16 January 929 – 1017 |

Succeeded by Hammudid dynasty |

| Preceded by Hammudid dynasty |

Ruling house of Caliphate of Córdoba 1023 – 1025 |

Succeeded by Hammudid dynasty |

| Preceded by Hammudid dynasty |

Ruling house of Caliphate of Córdoba 1026 – 1031 |

Caliphate Abolished See Taifa |

| Titles in pretence | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Abbasid dynasty |

Caliphate dynasty 16 January 929 – 1017 1023 – 1025 1026 – 1031 |

Succeeded by Abbasid dynasty |