Hyksos

| Hyksos / Hykussos in hieroglyphs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

|

ḥqȝ(w)-ḫȝst / ḥqȝ(w)-ḫȝswt[1] Heqa-chaset / Heqa-chasut[1] Ruler(s) of the foreign countries[1] | ||||||||

| Greek | Hykussos (Ὑκουσσώς, Ὑκσώς, Ὑξώς)[2] | |||||||

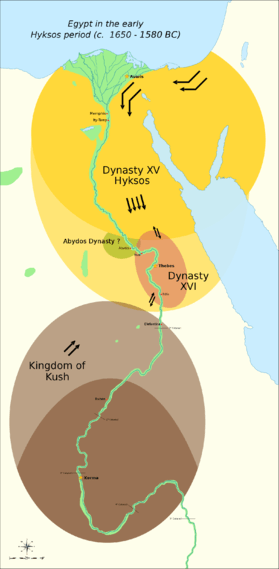

The Hyksos (/ˈhɪksɒs/; Egyptian ḥqꜣ(w)-ḫꜣswt, Egyptological pronunciation: heqa khasut, "ruler(s) of foreign lands"; Ancient Greek: Ὑκσώς, Ὑξώς) were a people of diverse origins, possibly from Western Asia,[3] who settled in the eastern Nile Delta some time before 1650 BC. The arrival of the Hyksos led to the end of the Thirteenth Dynasty and initiated the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt.[4] In the context of Ancient Egypt, the term "Asiatic" may refer to people native to areas east of Egypt.

Immigration by Canaanite populations preceded the Hyksos. Canaanites first appeared in Egypt at the end of the 12th Dynasty c. 1800 BC or c. 1720 BC and established an independent realm in the eastern Nile Delta.[5] The Canaanite rulers of the Delta regrouped and founded the Fourteenth Dynasty, which coexisted with the Egyptian Thirteenth Dynasty and was based in Itjtawy. The power of the 13th and 14th Dynasties progressively waned, perhaps due to famine and plague.[5][6]

In about 1650 BC, the Hyksos invaded the territory of both dynasties and established the Fifteenth Dynasty. The collapse of the Thirteenth Dynasty caused a power vacuum in the south, which may have led to the rise of the Sixteenth Dynasty, based in Thebes, and possibly of a local Abydos Dynasty.[5] The Hyksos eventually conquered both, albeit for only a short time in the case of Thebes. From then on, the 17th Dynasty took control of Thebes and reigned for some time in peaceful coexistence with the Hyksos kings, perhaps as their vassals. Eventually, Seqenenre Tao, Kamose and Ahmose waged war against the Hyksos and expelled Khamudi, their last king, from Egypt c. 1550 BC.[5]

The Hyksos practised horse burials, and their chief deity, their native storm god, Hadad, they associated with the Egyptian storm and desert god, Set.[3][7] The Hyksos were a mixed people of mainly Semitic-speaking origin.[3][8] The Hyksos are generally held to have contained Hurrian and Indo-European elements, particularly among the leadership,[9][10] but this has been vigorously opposed in some quarters, often for political reasons.[11]

The Hyksos brought several technical innovations to Egypt, as well as cultural imports such as new musical instruments and foreign loanwords.[12] The changes introduced include new techniques of bronze-working and pottery, new breeds of animals, and new crops.[12] In warfare, they introduced the horse and chariot,[13] the composite bow, improved battle axes, and advanced fortification techniques.[12] Because of these cultural advances, Hyksos' rule became decisive for Egypt's later empire in the Middle East during the New Kingdom.[12]

Etymology

The origin of the term "Hyksos" derives from the Egyptian expression heqau khaswet (or heqa-khaset; "rulers [of] foreign lands"), used in Egyptian texts such as the Turin King List to describe the rulers of neighbouring lands. This expression begins to appear as early as the late Old Kingdom of Egypt to refer to various Nubian chieftains and in the Middle Kingdom to refer to the Semitic-speaking chieftains of Syria and Canaan.

The word Hyksos probably originated as an Egyptian term meaning "rulers of foreign lands" (heqa-khaset), and it almost certainly designated the foreign dynasts rather than a whole nation.

Unique in the Ancient Greek language, the word ὑκσώς (trasl. hyksόs, with the rough breathing and the final grave accent, upon omega) is said to be derived from Egyptian. It is used with the unique meaning of "king shepherd", by Manetho (in Ios. Ap. I,14), priest and historian who wrote in Greek and knew the pre-Ptolemaic documents to support his history.[14] Until the decipherment of hieroglyphics Manetho was the only available source for a list of the egyptian kings. As a proof of its non-Greek origin, the word ὑκσώς (hyksōs) does not observe the rules of Ancient Greek accent, and is one of the few Greek words with a kappa followed by a sigma, instead of the more common Xi.

Origins

Josephus

In his Against Apion, the first-century AD historian Josephus debates the synchronism between the Biblical account of the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt and two Exodus-like events that the Egyptian historian Manetho (ca. 300 BC) apparently mentions. It is difficult to distinguish between what Manetho himself recounted, and how Josephus or Apion interpret him. Josephus identifies the Israelite Exodus with the first exodus mentioned by Manetho, when some 480,000 Hyksos "shepherd kings" (also referred to as just 'shepherds', as 'kings' and as 'captive shepherds' in his discussion of Manetho) left Egypt for Jerusalem.[15] The mention of "Hyksos" identifies this first exodus with the Hyksos period (16th century BC).

Josephus provides the earliest recorded instance of the much repeated false etymology of the term Hyksos, as a Hellenised form of the Egyptian phrase Hekw Shasu, meaning "Shepherd Kings". Scholars have only recently shown that the term derives from heqa-khase, a phrase meaning "rulers of foreign lands".[16]

Apion identifies a second exodus mentioned by Manetho when a renegade Egyptian priest called Osarseph led 80,000 "lepers" to rebel against Egypt. Then, Apion additionally conflates these with the Biblical Exodus, and contrary to Manetho, even alleges that this heretic priest changed his name to Moses.[17] Many scholars[18][19] do not interpret lepers and leprous priests as literally referring to a disease, but rather to a strange and unwelcome new belief system.

Way of settlement

The Hyksos are believed to have originated to the north of Palestine.[20] They destroyed Amorite rule Byblos in the 18th century BC, and then entered Egypt, bringing the Middle Kingdom to an end in the 17th century BC.[21] As to a Hyksos "conquest", some archaeologists depict the Hyksos as an invading horde of Asiatics.[22] Yet, others refer to a "creeping conquest", that is, a gradual infiltration of migrating nomads or semi-nomads who either slowly took over control of the country piecemeal or by a swift coup d'état put themselves at the head of the existing government.

Manetho's account, as recorded by Josephus, describes the appearance of the Hyksos in Egypt as an armed invasion by a horde of foreign barbarians who met little resistance, and who subdued the country by military force. He records that the Hyksos burnt their cities, destroyed temples, and led women and children into slavery.[23][24] It has been claimed[25] that new revolutionary methods of warfare ensured the Hyksos the ascendancy in their influx into the new emporia being established in Egypt's delta and at Thebes in support of the Red Sea trade. Herbert Eustis Winlock describes new military hardware, such as the composite bow, as well as the improved recurve bow, and most importantly the horse-drawn war chariot, as well as improved arrowheads, various kinds of swords and daggers, a new type of shield, mailed shirts, and the metal helmet.[25] The chariot had initially been introduced to the Middle East by Indo-Iranians.[26] The Hyksos were also responsible for introducing the horse into Egypt, and rode them in all their wars.[27] Chariots had earlier played a key role in the conquests of the Hittites in Anatolia, the Indo-Iranians in northern India, and the Mycenaeans in Greece.[28] As the chariot became an important weapon of the nobles and kings of that period, it became a symbol of power throughout Eurasia. Kings were portrayed on chariots, went to war in chariots, and were buried in chariots.

In recent years the idea of a simple Hyksos migration, with little or no war, has gained support.[29] According to this theory, the Egyptian rulers of the Thirteenth Dynasty were preoccupied with domestic famine and plague, and they were too weak to stop the new migrants from entering and settling in Egypt. Even before the migration, Amenemhat III carried out extensive building works and mining, through which the Hyksos might have arrived in Egypt and overthrown native Egyptian rule.[30] Supporters of the peaceful takeover of Egypt claim there is little evidence of battles or wars in general in this period.[31] They also maintain that the chariot didn't play any relevant role, e.g. no traces of chariots have been found at the Hyksos capital of Avaris, despite extensive excavation.[32] Janine Bourriau's cites lack of Hyksos-style wares as evidence against a Hyksos invasion.[33][34] Archaeologist Jacquetta Hawkes stated that the Hyksos were migrating Semites rather than a conquering horde.[35] John Van Seters in his book, The Hyksos: A New Investigation, argues that the Ipuwer Papyrus does not belong to the First Intermediate Period of Egyptian history (c. 2300-2200 BC), as previously thought, but rather to the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1700-1600 BC). He sees a gradual settlement of the Hyksos from Phoenicia-Palestine.[36]

Ethnicity

The Hyksos were probably an ethnically mixed people of largely Semitic origin.[21] They are believed to have originated from the north of Palestine.[20] The Hurrians also came to Canaan from this area.[20] They were possibly related to the Amorites, and may have included Habiru, a warlike group of largely Semitic peoples.[37]

Kamose, the last king of the Theban 17th Dynasty, refers to Apepi as a "Chieftain of Retjenu" in a stela that implies a Canaanite background for this Hyksos king: this is the strongest evidence for a Canaanite background for the Hyksos. Khyan's name "has generally been interpreted as Amorite "Hayanu" (reading h-ya-a-n) which the Egyptian form represents perfectly, and this is in all likelihood the correct interpretation."[38] Kim Ryholt furthermore observes the name Hayanu is recorded in the Assyrian king-lists for a "remote ancestor" of Shamshi-Adad I (c. 1813 BC) of Assyria, which suggests that it had been used for centuries prior to Khyan's own reign.[39] The issue of Sakir-Har's name, one of the three earliest Fifteenth Dynasty kings, also leans towards a West Semitic or Canaanite origin for the Hyksos rulers—if not the Hyksos peoples themselves.[40]

Contemporary with the Hyksos, there was a widespread Indo-Aryan expansion in central and south Asia. The arrival of the Hyksos in Egypt, along with the arrival of the Hurrians in Syria and the Kassites in Babylonia, has been connected with this migration.[41] The Hyksos used the same horsedrawn chariot as the Indo-Aryans, and Egyptian sources mention a rapid conquest. While the majority of the Hyksos are thought to have been Semitic, the Hyksos are usually believed to have contained Indo-Europeans and Hurrians among the leadership.[9] According to William L. Ochsenwald, is certain that the Hyksos contained Hurrians who were under Indo-Aryan rule and influence.[10] Claude Frédéric-Armand Schaeffer states that the Hyksos were related to the Hurrians and the Mitanni.[42] While the earliest names of Hyksos rulers are Semitic, names of later Hyksos rulers have been identified as having Indo-Aryan, Hurrian or uncertain etymologies.[43][44][45] These names are associated with the second wave of Hyksos invasion in the 17th century BC, which was composed of a mixed group of well organized warriors that were different from the earlier Asiatic Hyksos princes that arrived in Egypt in the 18th century BC.[43] John Bright cites this as evidence that there might have been an Indo-Aryan element among the Hyksos.[43] Philip Khuri Hitti wrote that the Hyksos were a mixed group which in addition to Semites included Hurrians, Hittites, Mitanni and Habiru.[46] Hitti connected the arrival of the Hyksos with the Indo-European migrations at the time, and cites the introduction of the horse and the chariot by them to Egypt as evidence of their Indo-European connections.[46] In any regards, the Indo-Europeans were few in number and rapidly became assimilated into the Semitic majority, which explains why only small traces of their separate linguistic identity survive.[47]

Since the early 20th century, the possibility of Hurrian, and particularly Indo-European influences among the Hyksos, has been hotly contested by non-European scholars.[11] This rejection gained currency after World War II as a reaction against Nazi antisemitism and racial theories.[11] Scholars rejecting Hurrian and Indo-European influences among the Hyksos typically pointed out that the majority of Hyksos names were Semitic, that there is a lack of archaeological evidence suggesting an large-scale invasion of Egypt from Syria during the arrival of the Hyksos, and chronologies which place the rise of the Hurrians before the emergence of the Hyksos.[11] Proponents of this theory include John Van Seters and J. R. Kupper.[9][48][49][50][51][52] Martin Bernal states that although he admires the political motives of those that deny Hurrian and Indo-European influences among the Hyksos, the evidence indicates that they are wrong.[11]

15th Dynasty

History

| Hyksos in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Traditionally, only the Fifteenth Dynasty rulers are called Hyksos. The Greek name "Hyksos" was coined by Manetho to identify the Fifteenth Dynasty of Asiatic rulers of northern Egypt. In Egyptian Hyksos means "ruler(s) of foreign countries", however, Josephus mistranslated Hyksos as "Shepherd Kings".[53]

By around 1700 BC, Egypt was fragmenting politically, with local kingdoms springing up in the northeastern delta area. One of these was that of King Nehesy, whose capital was at Avaris; he ruled over a population consisting largely of Syro-Canaanites who had settled in the area during the 12th Dynasty, and who were probably mainly soldiers, sailors, shipbuilders and workmen. His dynasty was probably replaced by a West-Semitic-speaking Syro-Canaanite dynasty that formed the basis of the later Hyksos kingdom, able to spread southwards because of the unstable political situation while aided by "an army, ships, and foreign connections."[54]

The earlier Fourteenth Dynasty of Egypt had been West Asian and Semitic-speaking; however, its pharaohs did not style themselves "Hyksos", and they seem to have been vassals of the Thirteenth Dynasty who oversaw a community of Asiatic merchants and shepherds who had been granted land in the Nile Delta. The Hyksos, by contrast, were largely Amoritic invaders who, capitalizing on a weak moment in Egypt's history, managed to conquer the entire country briefly as far south as Thebes (under Khyan, ca. 1582 BC).

The Hyksos had Canaanite names, as seen in those with names from ancient Semitic religion such as Anat or Baal. Several of their pharaohs did in fact adopt the Egyptian title hekw chasut (foreign overlords) for themselves, along with Egyptian throne names. They introduced new tools of warfare into Egypt, most notably the composite bow and the horse-drawn chariot.

The names, the order, and even the total number of the Fifteenth Dynasty rulers are not known with full certainty. The names appear in hieroglyphs on monuments and small objects such as jar lids and scarabs. In those instances in which Prenomen and Nomen do not occur together on the same object, there is no certainty that the names belong together as the two names of a single person. The Danish Egyptologist Kim Ryholt sums up the complex situation by stating that "there are only vague indications of the origin of the Fifteenth Dynasty" and concurring that the small number of surviving names of the Fifteenth Dynasty are "too few to allow for general conclusions" about the Hyksos' background in his 1997 study of the Second Intermediate Period.[55] Furthermore, Ryholt stresses that

- we also lack positive indications that any of the rulers of the Fifteenth Dynasty were related by blood, and, accordingly we could be dealing with a dynasty of mixed ethnic origin.[56]

The suspected rulers for the Fifteenth Dynasty are:

| Name | Dates |

|---|---|

| Sakir-Har | Named as an early Hyksos king on a doorjamb found at Avaris. Regnal order uncertain. |

| Khyan | c. 1620 BC |

| Apepi | c. 1595 BC to 1555 BC? |

| Khamudi | c. 1555 BC to 1545 BC? |

Manetho's history of Egypt is known only through the works of others, such as Against Apion by Flavius Josephus. These sources do not list the names of the six rulers in the same order. To complicate matters further, the spellings are so distorted that they are useless for chronological purposes; there is no close or obvious connection between the bulk of these names—Salitis, Beon or Bnon, Apachnan or Pachnan, Annas or Staan, Apophis, Assis or Archles—and the Egyptian names that appear on scarabs and other objects. The Turin king list affirms there were six Hyksos rulers, but only four of them are clearly attested as Hyksos kings from the surviving archaeological or textual records: 1. Sakir-Har, 2. Khyan, 3. Apophis and 4. Khamudi.

Khyan and Apophis are by far the best attested kings of this dynasty, whereas Sakir-Har is attested by only a single doorjamb from Avaris that bears his royal titulary. Khamudi is named as the last Hyksos king on a fragment from the Turin Canon. The hieroglyphic names of these Fifteenth Dynasty rulers exist on monuments, scarabs, and other objects.

Two Hyksos pharaohs remain unknown. Many scholars have suggested that they were Maaibre Sheshi, Aper-Anath, Samuqenu, Sekhaenre Yakbim or Meruserre Yaqub-Har (who are all attested by seals or scarabs in the Delta region) but, thus far, all that is certain is that they were Asiatic kings in the Egypt's Delta region. They could be either the remaining two Hyksos kings or were members of the previous Fourteenth Dynasty at Xois.

Range

The Hyksos kingdom was centered in the eastern Nile Delta and Middle Egypt and was limited in size, never extending south into Upper Egypt, which was under the control of Theban-based rulers, except briefly, for about three years, at the end of Khyan's reign and the beginning of Aphophis'. The Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty rulers established their capital and seat of government at Avaris.

The rule of these kings overlaps with that of the native Egyptian pharaohs of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Dynasties, better known as the Second Intermediate Period. The first pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty, Ahmose I, finally expelled the Hyksos from their last holdout at Sharuhen in Gaza by the sixteenth year of his reign.[57][58]

The independent native rulers in Thebes do seem, however, to have reached a practical modus vivendi with the later Hyksos rulers. This included transit rights through Hyksos-controlled Middle and Lower Egypt and pasturage rights in the fertile Delta. One text, the Carnarvon Tablet I, relates the misgivings of the Theban ruler's council of advisors when Kamose proposed moving against the Hyksos, who he claimed were a humiliating stain upon the holy land of Egypt. The councilors clearly did not wish to disturb the status quo:

[W]e are at ease in our (part of) Egypt. Elephantine (at the First Cataract) is strong, and the middle (of the land) is with us as far as Cusae [near modern Asyut]. The sleekest of their fields are plowed for us, and our cattle are pastured in the Delta. Emmer is sent for our pigs. Our cattle have not been taken away… He holds the land of the Asiatics; we hold Egypt[.][59]

It would appear as though Hyksos administration was accepted in most quarters, if not actually supported by many of their northern Egyptian subjects.

Not until the beginning of the Theban wars of liberation during the Seventeenth Dynasty are Theban wares again found in the Faiyum. Some texts indicate that while the Hyksos controlled the delta region administratively, the Thebans were too busy mining gold and making money off the Red Sea trade to care. Lower Egypt and Thebes functioned autonomously, and shared limited contact with each other.[60]

Relationship with the Egyptians

Scholars have taken the increasing use of scarabs and the adoption of some Egyptian forms of art by the Fifteenth Dynasty Hyksos kings and their wide distribution as an indication of their becoming progressively Egyptianized.[61] The Hyksos used Egyptian titles associated with traditional Egyptian kingship, and took the Egyptian god Set to represent their own titulary deity.[62] The native Egyptians viewed the Hyksos as non-Egyptian "invaders". When they were eventually driven out of Egypt, all traces of their occupation were erased.

No accounts survive recording the history of the period from the Hyksos perspective, only that of the native Egyptians who evicted the occupiers, in this case the rulers of the Eighteenth Dynasty who were the direct successor of the Theban Seventeenth Dynasty.[63] It was the latter who started and led a sustained war against the Hyksos. Some think that the native kings from Thebes had an incentive to demonize the Asiatic rulers in the North, thus accounting for the destruction of their monuments. Scholars such as John A. Wilson found that the description of the Hyksos as overpowering, irreligious foreign rulers had support from other sources.[64]

Theban offensive

Under Seqenenre Tao

The revolt which drove the Hyksos from Upper Egypt began in the closing years of the Seventeenth Dynasty at Thebes. Later New Kingdom literary tradition has brought one of these Theban kings, Seqenenre Tao, into contact with his Hyksos contemporary in the north, Apepi (also known as Apophis). The tradition took the form of a tale in which the Hyksos king Apepi sent a messenger to Seqenenre in Thebes to demand that the Theban sport of harpooning hippopotami be done away with; his excuse was that the noise of these beasts was such that he was unable to sleep in faraway Avaris. The real reason was probably that their main god was Set, who was represented as part man, part hippopotamus. Jan Assmann argues that because the Ancient Egyptians could never conceive of a "lonely" god lacking personality, Set the desert god, who was worshipped exclusively according to the tale, represented a manifestation of evil.[65] Perhaps the only historical information that can be gleaned from the tale is that Egypt was a divided land, the area of direct Hyksos control being in the north, but the whole of Egypt possibly paying tribute to the Hyksos kings.

Seqenenre participated in active diplomatic posturing, which probably consisted of more than simply exchanging insults with the Asiatic ruler in the North. He seems to have led military skirmishes against the Hyksos, and judging by the vicious head wounds on his mummy in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, he may have died during one of them. His son and successor, Kamose, the last ruler of the Seventeenth Dynasty at Thebes, is credited with the first significant victories in the Theban-led war against the Hyksos.

Under Kamose

Kamose sailed north from Thebes at the head of his army in his third regnal year. He surprised and overran the southernmost garrison of the Hyksos at Nefrusy, just north of Cusae (near modern Asyut), and Kamose then led his army as far north as the neighborhood of Avaris itself. Though the city was not taken, the fields around it were devastated by the Thebans. A second stele discovered at Thebes continues the account of the war broken off on the Carnarvon Tablet I, and mentions the interception and capture of a courier bearing a message from Apepi at Avaris to his ally, the ruler of the Kingdom of Kush (modern Sudan), requesting the latter's urgent support against the threat posed by Kamose's activities against both their kingdoms. Kamose promptly ordered a detachment of his troops to occupy the Bahariya Oasis in the Libyan Desert to control and block the desert route to the south. Kamose, called "the Strong," then sailed back up the Nile to Thebes for a joyous victory celebration, after what was probably not much more than a surprise spoiling raid in force that caught the Hyksos off guard. His Year Three is the only date attested for Kamose and he may have died shortly after the battle from wounds.[54]

By the end of the reign of Apepi, perhaps the second-to-last Hyksos king of the Fifteenth Dynasty, the Hyksos had been routed from Middle Egypt and had retreated northward and regrouped in the vicinity of the entrance of the Faiyum at Atfih. This Fifteenth Dynasty pharaoh had outlived his first Egyptian contemporary, Seqenenra Tao II, and was still on the throne (albeit of a much reduced kingdom) at the end of Kamose's reign. The last Hyksos ruler of the Fifteenth Dynasty, Khamudi, undoubtedly had a relatively short reign that fell within the first half of the reign of Ahmose I, Kamose's successor and the founder of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Under Ahmose

Ahmose I, who is regarded as the first pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt may have been on the Theban throne for some time before he resumed the war against the Hyksos.

The details of his military campaigns are taken from the account on the walls of the tomb of Ahmose, son of Ebana, a soldier from El-Kab, a town in southern Upper Egypt, whose father had served under Seqenenra Tao, and whose family had long been nomarchs of the districts. It seems that several campaigns against the stronghold at Avaris were needed before the Hyksos were finally dislodged and driven from Lower Egypt. When this occurred is not known with certainty. Some authorities place the expulsion as early as Ahmose's fourth year, while Donald B. Redford, whose chronological structure has been adopted here, places it as late as the king's fifteenth year. The Ahmose who left the inscription states that he followed on foot as his King Ahmose rode to war in his chariot (the first mention of the use of the horse and chariot by the Egyptians); in the fighting around Avaris he captured prisoners and carried off several hands (as proof of slain enemies), which when reported to the royal herald resulted in his being awarded the "Gold of Valor" on three separate occasions. The actual fall of Avaris is only briefly mentioned: "Then Avaris was despoiled. Then I carried off spoil from there: one man, three women, a total of four persons. Then his majesty gave them to me to be slaves."[66]

After the fall of Avaris, the fleeing Hyksos were pursued by the Egyptian army across northern Sinai Peninsula and into the southern Levant. Here, in the Negev desert between Rafah and Gaza, the fortified town of Sharuhen was reduced after, according to the soldier from El-Kab, a long three-year siege operation. How soon after the sack of Avaris this Asiatic campaign took place is uncertain. One can reasonably conclude that the thrust into southern Canaan probably followed the Hyksos' eviction from Avaris fairly closely, but, given a period of protracted struggle before Avaris fell and possibly more than one season of campaigning before the Hyksos were shut up in Sharuhen, the chronological sequence must remain uncertain.

Later times

The Hyksos continued to play a role in Egyptian literature as a synonym for "Asiatic" down to Hellenistic times. The term was frequently evoked against such groups as the Semites settled in Aswan or the delta, and this may have led the Egyptian priest and historian Manetho (or Ptolemaeus the Mendesian) to identify the coming of the Hyksos with the sojourn in Egypt of Joseph and his brothers, and led to some authors identifying the expulsion of the Hyksos with the Exodus. For instance, Justin Martyr says:

- Moses is mentioned as the leader and ruler of the Jewish nation. In this way he is mentioned both by Polemon in the first book of his Hellenics and by Apion son of Posidonius in his book against the Jews, and in the fourth book of his history, where he says that during the reign of Inachus over Argos the Jews revolted from Amasis king of the Egyptians and that Moses led them. And Ptolemaeus the Mendesian, in relating the history of Egypt, concurs in all this.[67]

With the chaos at the end of the 19th Dynasty, the first pharaohs of the 20th Dynasty in the Elephantine Stele and the Harris Papyrus reinvigorated an anti-Hyksos stance to strengthen their nativist reaction towards the Asiatic settlers of the north, who may again have been expelled from the country. Setnakht, the founder of the 20th Dynasty, records in a Year 2 stela from Elephantine that he defeated and expelled a large force of Asiatics who had invaded Egypt during the chaos between the end of Twosret's reign and the beginning of the 20th Dynasty and captured much of their stolen gold and silver booty.

The story of the Hyksos was known to the Greeks,[68] who attempted to identify it within their own mythology with the expulsion from Egypt of Belos (Baal?[69]) and the daughters of Danaos, associated with the origin of the Argive Dynasty.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Rainer Hannig: Großes Handwörterbuch Ägyptisch-Deutsch : (2800-950 v. Chr.). von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9, p. 606 and 628–629.

- ↑ Folker Siegert: Flavius Josephus: Über die Ursprünglichkeit des Judentums. p. 111.

- 1 2 3 "Hyksos (Egyptian dynasty)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ↑ Redford D., Egypt, Canaan and Israel in ancient times, 1992

- 1 2 3 4 Ryholt, K. S. B.; Bülow-Jacobsen, Adam (1997). The Political Situation in Egypt During the Second Intermediate Period, C. 1800-1550 B.C. Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-7289-421-8.

- ↑ Manfred Bietak: Egypt and Canaan During the Middle Bronze Age, BASOR 281 (1991), pp. 21-72 see in particular page 38

- ↑ Morenz, Siegfried (2013). Egyptian Religion. Routledge. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-136-54249-7.

- ↑ Starr, Chester G. (1991). A History of the Ancient World. Oxford University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-19-506628-9.

- 1 2 3 Stiebing, Jr., William H. "Hyksos Burials in Palestine: A Review of the Evidence". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 30 (2): 110–117. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

The Hyksos have usually been identified as a mixture of peoples, primarily West Semites, but with Indo-Europeans and Hurrians among the leadership

- 1 2 Ochsenwald, William L. "Syria: Early history". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

The mixed multitude of the Hyksos certainly included Hurrians, who, not being Aryans themselves, were under the rule and influence of Aryans and learned from them the use of light chariots and horses in warfare, which they introduced into Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bernal 1987, p. 39: "The revolusion after the Second World War against anti-Semitism and theories of an Aryan 'master race' appears to have had a major impact on attitudes towards the Hyksos. Scholars now tended to dismiss the possibility of Hurrian, let alone Indo-European, elements among the Hyksos... as much as I applaud the political inclinations of those who have tried to deny a Hurrian or Indo-Iranian influence on the Hyksos, I think they are wrong, and the evidence does indicate a Hurrian and possibly even an Indo-Iranian element among the Hyksos and, what is more, this element was probably associated with chariotry."

- 1 2 3 4 John R. Baines; Peter F. Dorman. "Ancient Egypt: The Second Intermediate Period". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

The effect of these changes was to bring Egypt, which had been technologically backward, onto the level of southwestern Asia. Because of these advances and the perspectives it opened up, Hyksos rule was decisive for Egypt’s later empire in the Middle East.

- ↑ p5. 'The Encyclopedia of Military History' (4th edition 1993), Dupuy & Dupuy.

- ↑ Lorenzo Rocci (1993). Vocabolario Greco-Italiano (in Italian). Città di Castello (Perugia): Società Editrice Dante Alighieri.

; this word was not quoted in the A Greek-English Lexicon, years editions of 1853 and of 1893.

And also the full acronym used for title of Manetho's work - ↑ Josephus, Flavius, Against Apion, 1:86–90.

- ↑ Finkelstein, Israel and Silberman, Neil Asher, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, 2001, The Free Press, New York City, ISBN 0-684-86912-8 p. 54

- ↑ Josephus, Flavius, Against Apion, 1:234–250.

- ↑ Miriam - From Prophet to Leper

- ↑ Egyptian Account of the Leper's Exodus

- 1 2 3 "Canaan". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

Other invaders included the Egyptians and the Hyksos, a group of Asian peoples who seem to have migrated there from north of Palestine. The Hurrians (the Horites of the Old Testament) also came to Canaan from the north.

- 1 2 Barnett, Richard David; Ochsenwald, William L.; Bugh, Glenn Richard. "Lebanon: Origins and relations with Egypt". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

In the 18th century bce new invaders, the Hyksos, destroyed Amorite rule in Byblos and, passing on to Egypt, brought the Middle Kingdom to an end (c. 1630 bce). Little is known about the Hyksos’ origin, but they seem to have been ethnically mixed, including a considerable Semitic element, since the Phoenician deities El, Baal, and Anath figured in their pantheon.

- ↑ See p. 37 in: Gunn, Battiscombe (1919). "New Renderings of Egyptian Texts: II. The Expulsion of the Hyksos". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 5 (1): 36–56. Retrieved 22 August 2018 – via JSTOR. (Registration required (help)).

- ↑ History of Egypt from the Earliest Time to the Persian Conquest, James Henry Breasted, p. 216, republished 2003, ISBN 0-7661-7720-3

- ↑ Flavius Josephus, Against Apion, I:75–77. "By main force they easily seized it without striking a blow; and having overpowered the rulers of the land, they then burned our cities ruthlessly, razed to the ground the temples of gods… Finally, they appointed as king one of their number whose name was Salitis. He had his seat at Memphis, levying tribute from Upper and Lower Egypt and always leaving garrisons behind in the most advantageous positions."

- 1 2 Winlock, Herbert E., The Rise and Fall of the Middle Kingdom in Thebes.

- ↑ Guilmartin, John F. "Military Technology". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

Around 1600 bce, Iranian tribes introduced the war-horse into Mesopotamia from the north, along with the light two-wheeled chariot. The Hyksos apparently introduced the chariot into Egypt shortly thereafter, by which time it was a mature technology.

- ↑ Casolani, Charles Edward. "Horsemanship". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

Among the earliest peoples to fight and hunt on horseback were the Hittites, the Assyrians, and the Babylonians; at the same time (about 1500 bce) the Hyksos, or Shepherd Kings, introduced horses into Egypt and rode them in all their wars.

- ↑ "Chariot". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

Chariotry contributed to the victories, in the 2nd millennium bc, of the Hyksos in Egypt, the Hittites in Anatolia, the Aryans in northern India, and the Mycenaeans in Greece.

- ↑ Booth, Charlotte. The Hyksos Period in Egypt. p.10. Shire Egyptology, 2005. ISBN 0-7478-0638-1

- ↑ Callender, Gae, "The Middle Kingdom Renaissance," in Ian Shaw, ed. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, 2003 ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7 p. 157. "The large intake of Asiatics, which seems to have occurred partly in order to subsidize the extensive building work, may have encouraged the so-called Hyksos to settle in the delta, thus leading eventually to the collapse of native Egyptian rule."

- ↑ Booth, Charlotte. The Hyksos Period in Egypt. p.10. Shire Egyptology. 2005. ISBN 0-7478-0638-1

- ↑ Bard, Kathryn (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-415-18589-9.

- ↑ The Hyksos: New Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, ed. Eliezer Oren, University of Pennsylvania 1997. cf. Janine Bourriau's chapter of the archaeological evidence covers pages 159-182

- ↑ The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, editor Ian Shaw, p. 195, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-19-280293-3

- ↑ Jacquetta Hawkes. (1963). The World of the Past, p. 444 "It is no longer thought that the Hyksos rulers ... represent the invasion of a conquering horde of Asiatics ... they were wandering groups of Semites who had long come to Egypt for trade and other peaceful purposes."

- ↑ Seters, John Van (1 April 2010). The Hyksos: A New Investigation. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-60899-533-2.

On the basis of the archaeological investigation, the foreigners of Egypt are seen as a geographical extension of the corresponding culture of Phoenicia-Palestine in the MB II period, a culture with a highly advanced urban society. This civilization of the Levant has its roots in the Amurrite world of both Syria and Mesopotamia in the Old Babylonian period, and has a direct heir in the so-called Canaanite world of the Late Bronze Age. The MB II period began during the Middle Kingdom, and by the end of the Twelfth Dynasty the whole of Phoenicia-Palestine was under the influence of Egypt, with diplomatic ties and active cooperation between the rulers of the various city-states and the rulers of Egypt. During the early Thirteenth Dynasty, the foreigners had much freer access into Egypt. Many of them rose to places of high honor in the administration of the country.

- ↑ Kenyon, Kathleen Mary; Bugh, Glenn Richard. "Palestine". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

These were probably introduced by the Asiatic Hyksos, possibly related to the Amorites, who secured control of northern Egypt about 1630. The Hyksos may have included elements of a grouping of people, largely Semitic, called the Habiru or Hapiru (Egyptian ʿApiru).

- ↑ Ryholt, Kim S.B.. The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period c.1800-1550 B.C., Museum Tuscalanum Press (1997) p.128.

- ↑ Ryholt, p.128

- ↑ Ryholt, pp.127–128. "[Sakir-Har] is evidently a theophorous name compounded with hr, Canaanite harru, [or] 'mountain.' This sacred or deified mountain is attested in at least two other names, both West Semitic (Yaqub-Har and Anat-her), and so there is reason to suspect that the present name also may be West Semitic. The element skr seems identical to śkr, 'to hire, to reward,' which occurs in several Amorite names. Assuming that śkr takes a nominal form as in the names sa-ki-ru-um and sa-ka-ŕu-um, the name should be transliterated as either Sakir-Har or Sakar-Har. The former two names presumably mean 'the Reward.' Accordingly, the name here under consideration would mean 'Reward of Har."

- ↑ & Hollar 2011, pp. 62–63

- ↑ Schaeffer, Claude Frédéric-Armand. "Ugarit". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

During the 18th and 17th centuries bce, Ugarit was apparently under the control of new tribes related to the Hyksos, probably mainly Hurrians or Mitannians, who mutilated the Egyptian monuments.

- 1 2 3 Bright 2000, p. 60

- ↑ Drews 1994, p. 57

- ↑ Drews 1994, p. 254

- 1 2 Hitti 2004, p. 146 "Originally a horde, an unclassified goulash of humanity which the melting-pot of the eastern Mediterranean had spilled over the edge and washed down into Egypt, the Hyksos represented a movement which came to include — besides Semites — non-Semitic Hurrians, Hittites and Mitannians. There were also Khahiru among them. The movement may have had connections with that of the Indo-Iranians or Indo-Europeans in the north, including the Kassites of Mesopotamia. That the crystallizing element was Canaanite or Amoritc may be evinced by the names of their earliest rulers as they appear on monuments and scarabs... Hyksos connection with the Indo-European civilization to the north is attested by their use of the horse, a valued possession shared by the Kassites. Together with the horse which they introduced into Syria and thence into Egypt, the Hyksos brought the chariot into both lands.

- ↑ McNeill 2009, p. 112

- ↑ Martin Bernal (1987). Black Athena: The archaeological and documentary evidence. p. 40.

- ↑ Marc Van De Mieroop (2011). A History of Ancient Egypt. p. 149.

- ↑ Michael C. Astour (1967). Hellenosemitica: An Ethnic and Cultural Study in West Semitic Impact on Mycenaean Greece. p. 93.

- ↑ John Van Seters (2010). The Hyksos: A New Investigation. p. 185.

- ↑ J.R Kupper (1963). The Cambridge Ancient History, Northern Mesopotamia and Syria. p. 38.

- ↑ Lloyd, A.B. (1993). Herodotus, Book II: Commentary, 99-182 v. 3. Brill. p. 76. ISBN 978-90-04-07737-9. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- 1 2 Bietak, Manfred "Second Intermediate Period, overview" in Kathryn Bard, ed., Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt Routledge 1999 ISBN 0-415-18589-0 p57

- ↑ Kim Ryholt, The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period c.1800-1550 B.C., Museum Tuscalanum Press, 1997. p.126

- ↑ Ryholt, op. cit., p.126 An example given by Ryholt "is the family of the kings Warad-Sin and Rim-Sin of Larsa. Their father had been the ruler of two Amorite tribes, but both he and their grandfather had Elamite names, while they themselves had Akkadian names, and a sister of theirs had a Sumerian name.

- ↑ Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt, p.193. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988.

- ↑ Redford, Donald B. History and Chronology of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt: Seven Studies, pp.46–49. University of Toronto Press, 1967.

- ↑ Pritchard (ed.), Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (ANET), pp 232f.

- ↑ James K. Hoffmeier, Book Review of The Hyksos: New Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, ed. Eliezer Oren, University of Pennsylvania 1997. in JEA 90 (2004), p.27

- ↑ Booth, Charlotte. The Hyksos Period in Egypt. p.15-18. Shire Egyptology. 2005. ISBN 0-7478-0638-1

- ↑ Booth, Charlotte. The Hyksos Period in Egypt. p.29-31. Shire Egyptology. 2005. ISBN 0-7478-0638-1

- ↑ cf. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, editor Ian Shaw, p. 186, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-19-280293-3

- ↑ The Culture of Ancient Egypt, John Albert Wilson, p. 160, University of Chicago Press, org. pub 1956 -still in print 2009, ISBN 0-226-90152-1

- ↑ Of God and Gods, Jan Assmann, p47-48, University of Wisconsin Press, 2008, ISBN 0-299-22550-X

- ↑ ANET, p.233f

- ↑ Justin Martyr, Hortatory Address to the Greeks (ch 9) in Volume 1 of Roberts, A., & Donaldson, J. (1950). The Ante-Nicene Fathers: Translations of the writings of the Fathers down to A.D. 325. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., page 277.

- ↑ E.g. Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca ,2.1.4.

- ↑ Karl Kerenyi, The Heroes of the Greeks 1959 (1974:30): "Belos, whose name reproduces the Phoenician Ba'al, 'Lord'".

References

- Aharoni, Yohanan and Michael Avi-Yonah, The MacMillan Bible Atlas, Revised Edition, pp. 30–31 (1968 & 1977 by Carta Ltd.).

- von Beckerath, Jürgen. Untersuchungen zur politischen Geschichte der zweiten Zwischenzeit in Ägypten (1965) [Ägyptologische Forschungen, Heft 23]. Basic to any study of this period.

- Bernal, Martin (1987). Black Athena: The archaeological and documentary evidence. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 081351584X.

- Bietak M., Avaris, the Capital of the Hyksos. Recent Excavations at Tell el-Dab'a, 1996

- Bimson, John J. Redating the Exodus. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1981. ISBN 0-907459-04-8

- Bright, John (2000). "A History of Israel". Westminster John Knox Press. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Charlotte Booth: The Hyksos period in Egypt. Princes Risborough, Shire 2005. ISBN 0-7478-0638-1

- Drews, Robert (1 October 1994). "The Coming of the Greeks: Indo-European Conquests in the Aegean and the Near East". Princeton University Press. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Gardiner, Sir Alan. Egypt of the Pharaohs (1964, 1961). Still the classic work in English. See pp. 61–71 for his examination of chronology.

- Gibson, David J., Whence Came the Hyksos, Kings of Egypt?, 1962

- Hayes, William C. "Chronology: Egypt—To End of Twentieth Dynasty," in Chapter 6, Volume 1 of The Cambridge Ancient History, Revised Edition. Cambridge, 1964. With excellent bibliography up to 1964. This is CAH's chronology volume: A basic work.

- Hayes, William C. "Egypt: From the Death of Ammenemes III to Seqenenre II," in Chapter 2, Volume 2 of The Cambridge Ancient History, Revised Edition (1965) (Fascicle 6).

- Helck, Wolfgang. Die Beziehungen Ägyptens zu Vorderasien im 3. und 2. Jahrtausend v. Chr. (1962) [Ägyptologische Abhandlungen, Band 5]. An important review article that should be consulted is by William A. Ward, in Orientalia 33 (1964), pp. 135–140.

- Hitti, Philip Khuri (2004). History of Syria: Including Lebanon and Palestine. Gorgias Press. ISBN 1593331193.

- Hollar, Sherman (2011). Mesopotamia. Britannica Educational Publishing. ISBN 1-61530-575-0. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- Hornung, Erik. Untersuchungen zur Chronologie und Geschichte des Neuen Reiches (1964) [Ägyptologische Abhandlungen, Band 11]. With an excellent fold-out comparative chronological table at the back with 18th, 19th, and 20th Dynasty dates.

- James, T.G.H. "Egypt: From the Expulsion of the Hyksos to Amenophis I," in Chapter 2, Volume 2 of The Cambridge Ancient History, Revised Edition (1965) (Fascicle 34).

- McNeill, William H. (2009). The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226561615.

- Montet, Pierre. Eternal Egypt (1964). Translated by Doreen Weightman.

- Eliezer D. Oren (Hrsg.): The Hyksos, new historical and archaeological perspectives. Kongressbericht. University Museum Philadelphia. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia 1997. ISBN 0-924171-46-4

- Pritchard, James B. (Editor). Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament(ANET), 3rd edition. (1969). This edition has an extensive supplement at the back containing additional translations. The standard collection of excellent English translations of ancient Near Eastern texts.

- Redford, Donald B. History and Chronology of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt: Seven Studies. (1967).

- Redford, Donald B. "The Hyksos Invasion in History and Tradition," Orientalia 39 (1970), 1-52.

- Redford Donald B. Egypt, Canaan and Israel in ancient times, 1992

- K. Ryholt. The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period c.1800-1550 B.C. (1997) by Museum Tuscalanum Press.

- Säve-Söderbergh, T. "The Hyksos Rule in Egypt," Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 37 (1951), pp. 53–71.

- Van Seters, John. The Hyksos: A New Investigation (1967).

- Winlock, H. E. The Rise and Fall of the Middle Kingdom in Thebes (1947). Still a classic with much important information.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hyksos. |

- The Hyksos, Kings of Egypt and the land of Edom based on the 1962 book by David J. Gibson

- The Hyksos