Odaenathus

| Odaenathus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

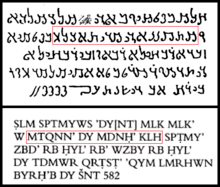

King of Palmyra King of Kings of the East (Western Aramaic: Mlk Mlk DY MDNH) | |||||

Odenaethus' alleged bust | |||||

| King of Kings of the East | |||||

| Reign | 263–267 | ||||

| Predecessor | Title created | ||||

| Successor | Vaballathus | ||||

| King of Palmyra | |||||

| Reign | 260–267 | ||||

| Predecessor | Himself as Lord of Palmyra | ||||

| Successor | Vaballathus | ||||

| Ras (Lord) of Palmyra | |||||

| Reign | 240s–260 | ||||

| Predecessor | Office established | ||||

| Successor | Himself as King | ||||

| Born |

c. 220 Palmyra, Syria | ||||

| Died |

267 (aged 46–47) Heraclea Pontica or Homs | ||||

| Spouse | Zenobia | ||||

| Issue |

Hairan I Vaballathus Hairan II | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Odaenathus | ||||

| Father | Hairan | ||||

Septimius Udhayna, Latinized as Odaenathus (Palmyrene: ![]()

The defeat and captivity of emperor Valerian at the hands of the Sassanian emperor Shapur I in 260 left the eastern Roman provinces largely at the mercy of the Persians. Odaenathus stayed on the side of Rome; assuming the title of king, he led the Palmyrene army and fell upon the Persians before they could cross the Euphrates to the eastern bank, and inflicted upon them a considerable defeat. Then, Odaenathus took the side of emperor Gallienus, the son and successor of Valerian, who was facing the usurpation of Fulvius Macrianus. The rebel declared his sons emperors, leaving one in Syria and taking the other with him to Europe. Odaenathus attacked the remaining usurper and quelled the rebellion. He was rewarded many exceptional titles by the emperor who formalized his self-established position in the East. In reality, the emperor could have done little but to accept the declared nominal loyalty of Odaenathus.

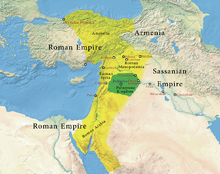

In a series of rapid and successful campaigns starting in 262, he crossed the Euphrates and recovered Carrhae and Nisibis. He then took the offensive to the heartland of Persia, and arrived at the walls of its capital Ctesiphon. The city withstood the short siege but Odaenathus reclaimed the entirety of Roman lands occupied by the Persians since the beginning of their invasions in 252. Odaenathus celebrated his victories and declared himself King of Kings, crowning his son Hairan I as co-king. By 263, Odaenathus was in effective control of the Levant, Mesopotamia and Anatolia's eastern region.

Odaenathus observed all due formalities towards the emperor, but in practice ruled as an independent monarch. In 266, the king launched a second invasion of Persia but had to abandon the campaign and head north to Bithynia to repel the attacks of Germanic riders besieging the city of Heraclea Pontica. He was assassinated in 267 during or immediately after the Anatolian campaign, together with Hairan. The identities of the perpetrator or the instigator are unknown and many stories, accusations and speculations exist in ancient sources. He was succeeded by his son Vaballathus under the regency of his widow Zenobia, who used the power established by Odaenathus to forge the Palmyrene Empire in 270.

Family and name

_of_Dura%2C_from_the_Temple_of_the_Gadde.jpg)

The king appears to be of mixed Arab and Aramean descent;[2] his name, the name of his father, Hairan, and that of his grandfather, Wahb-Allat, are Arabic,[note 1][4] while Nasor, his great-grandfather, has an Aramaic name.[5] Nasor might not have been the great-grandfather of Odaenathus but rather a distant ancestor;[6] this led some scholars, such as Lisbeth Soss Fried and Javier Teixidor, to consider the origin of the family to be Aramean.[7][5] Byzantine historians of the sixth century, such as Procopius, referred to him as "King of the Saracens [of the Arabs]".[7] Zosimus asserted that Odaenathus descended from "illustrious forebears",[5] but the position of the family in Palmyra is debated; it was probably part of the wealthy mercantile class.[8] Alternatively, the family may have belonged to the tribal leadership which amassed a fortune as landowners and patrons of the Palmyrene caravans.[note 2][2] In Dura-Europos, a relief dated to 159 was commissioned by Hairan son of Maliko son of Nasor; this Hairan might have been the head of the Palmyrene trade colony in Dura-Europos and probably belonged to the same family as Odaenathus.[10][11] The "Nasor" father of Maliko mentioned in the Dura-Europos inscription could therefore be Odaenathus' great-great-great grandfather.[12]

"Odaenathus" is the Greek version of the king's name; he was born Septimius Udhayna c. 220.[note 3][14] Written in Palmyrene as Sptmyws 'Dynt;[15] "Udhayna" is the king's personal name,[16] an Arabic one that means "little ear".[17] "Septimius" was the family's gentilicium (surname) adopted as an expression of loyalty to the Roman Severan dynasty,[18] whose emperor Septimius Severus granted the family Roman citizenship in the late second century.[19]

Odaenathus I

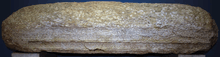

In the Temple of Bel at Palmyra, a stone block with a sepulchral inscription was found mentioning the building of a tomb and recording the genealogy of the builder: Odaenathus, son of Hairan, son of Wahb Allat, son of Nasor.[20][21] Traditional scholarship believed the builder to be an ancestor of the king and he was given the designation "Odaenathus I".[note 4][23] In an inscription dated to 251, the name of the "Ras" (lord) of Palmyra, Hairan, son of Odaenathus, is written,[24] and he was thought to be the son of Odaenathus I.[23]

Prior to the 1980s, the earliest known inscription attesting king Odaenathus was dated to 257, leading traditional scholarship to believe that Hairan, Ras of Palmyra, was the father of the king and that Odaenathus I was his grandfather.[note 5][23][26] However, an inscription published in 1985 by archaeologist Michael Gawlikowski and dated to 252 mentions king Odaenathus as a "Ras" and records the same genealogy found in the sepulchral inscription, confirming the name of king Odaenathus' grandfather as Wahb Allat.[23][24][27] Therefor, it is certain that king Odaenathus is the builder of the tomb, ruling out the existence of "Odaenathus I".[22][23] The Ras Hairan mentioned in the 251 inscription is identical with Odaenathus' elder son and co-ruler, prince Hairan I.[23][28]

Rise

Palmyra was an autonomous city subordinate to Rome and part of Syria Phoenice province.[29] Odaenathus descended from an aristocratic family, albeit not a royal one as the city was ruled by a council and had no tradition of hereditary monarchy.[30][31][32] Bilingual inscriptions from Palmyra record the title of the Palmyrene ruler as "Ras" in Palmyrene and Exarchos in Greek, meaning the "Lord of Palmyra".[33] The title was created for Odaenathus,[34] and was not a usual title in the Roman Empire or a part of the traditional Palmyrene governance institutions;[35][36] whether it indicated a military or a priestly position is unknown,[37] but the military role is more likely.[38]

The rise of the aggressive Sasanian Empire in 224 and the Iranian incursions which affected Palmyrene trade,[39] combined with the weakness of the Roman Empire, were probably the reasons behind the Palmyrene council's decision to elect a lord for the city in order for him to lead a strengthened army.[8][34][40] The "Ras" title enabled the bearer to effectively deal with the Sassanid threat, in that it probably vested him with supreme civil and military authority; previously, the Palmyrene army had been decentralized under the command of several generals.[34]

Ras of Palmyra

An undated inscription refers to Odaenathus as a Ras and records the gift of a throne to him by a Palmyrene citizen named "Ogeilu son of Maqqai Haddudan Hadda", which confirms the supreme character of Odaenathus' title.[35] The earliest known inscriptions mentioning the title are dated to October 251 and April 252; the 251 inscription refers to Odaenathus' eldest son Hairan I as Ras while the 252 inscription mentions Odaenathus with that title.[41][42] Hairan I was apparently elevated to co-lordship by his father.[42] Although the written evidence for Odaenathus' lordship dates to 251,[note 6][35] it is possible that he acquired the title as early as the 240s; following the death of the Roman emperor Gordian III in 244 during a campaign against Persia, the Palmyrenes might have elected Odaenathus to defend the city.[35]

Odaenathus was described as Roman senator in the undated tomb inscription and Hairan I was mentioned with the same title in the 251 inscription.[44] Scholarly opinions vary on the exact date of Odaenathus' elevation to the position;[35] Gawlikowski and Jean Starcky maintain that the senatorial rank predates the Ras elevation.[44] Udo Hartmann concludes that Odaenathus first became a Ras in the 240s, then a senator in 250.[44] Another possibility is that the senatorial rank and lordship occurred simultaneously; Odaenathus was chosen as a Ras following Gordian's death, then, after Philip the Arab concluded a peace with the Persians, the emperor ratified Odaenathus' lordship and admitted him to the senate to guarantee Palmyra's continuous subordination.[35]

As early as the 240s, Odaenathus bolstered the Palmyrene army, recruiting the desert nomads and increasing the numbers of the Palmyrene heavy cavalry units (clibanarii).[34][45] In 252, the Persian emperor, Shapur I, started a full-scale invasion of the Roman provinces in the east.[46][47] During the second campaign of the invasion, Shapur conquered Antioch and headed south where his advance was checked in 253 by Emesa's priest-king Uranius Antoninus.[48] The events of 253 were mentioned in the works of the sixth-century historian John Malalas who also mentioned a leader by the name "Enathus" inflicting a defeat upon the retreating Shapur near the Euphrates.[48] "Enathus" is probably identical with Odaenathus,[49] and while Malalas' account indicates that Odaenathus defeated the Persians in 253,[50] there is no proof that the Palmyrene leader engaged Shapur before 260 and Malalas' account seems to be confusing Odaenathus' future actions during 260 with the events of 253.[51]

Shapur I destroyed the Palmyrene trade colonies all along the Euphrates (including the colonies at Anah in 253 and at Dura-Europos in 256);[52] Peter the Patrician says that Odaenathus approached Shapur to negotiate Palmyrene interests but was rebuffed and the gifts sent to the Persians were thrown into the river.[48][49][53] The date for the attempted negotiations is debated; some scholars, including John F. Drinkwater, set the event in 253 while others such as Alaric Watson set it in 256 following the destruction of Dura-Europos.[41][49]

Governor of Syria Phoenice

Several inscriptions dating to the end of 257 or early 258 show Odaenathus bearing the title "ὁ λαμπρότατος ὑπατικός" (Clarissimus Consularis);[25][50][54] this could be a mere honorific or a sign that he was appointed as the Legatus of Phoenice.[37][55] However, the title (ὁ λαμπρότατος ὑπατικός) was sometimes used in Syria to denote the provincial governor and William Waddington proposed that Odaenathus was indeed the governor of Phoenice.[note 8][25][5]

Five of the inscriptions mentioning Odaenathus as consul are dated to the Seleucid year 569 (258 AD) during which no governor for Phoenice is attested, which might indicate that this was Odaenathus' year of governorship.[56] In the city of Tyre, Phoenice's capital, the lines "To Septimius Odaenathus, the most illustrious. The Septimian colony of Tyre" were found inscribed on a marble base;[56][57] the inscription is not dated and if it was set after 257 then it indicates that Odaenathus was appointed as the governor of the province.[56]

These speculations cannot be proven without doubt but as a governor, Odaenathus would have been the highest authority in the province and above any legionary commander and provincial officials; this would make him the commander of the Roman forces in the province.[56] Whatever the case may be, starting from 258, Odaenathus strengthened his position and extended his political influence in the region.[37] By 260, Odaenathus held the rank, credibility and power to pacify the Roman east following the Battle of Edessa.[56]

Edessa

Faced with Shapur's third campaign,[58] the Roman emperor Valerian marched against the Persian monarch but was defeated near Edessa in late spring 260 and taken as a prisoner.[59] The Persian emperor then ravaged Cappadocia, Cilicia and claimed to have captured Antioch, the metropolis of Syria.[note 9][60] Taking advantage of the situation, Fulvius Macrianus, the commander of the imperial treasury, declared his sons Quietus and Macrianus Minor as joint emperors in August 260 opposing Valerian's son Gallienus.[note 10][61] Fulvius Macrianus took Antioch as his center and organized the resistance against Shapur; he dispatched Balista, his praetorian prefect, to Anatolia.[61] Shapur was defeated in the region of Sebaste at Pompeiopolis, prompting the Persians to evacuate Cilicia while Balista went back to Antioch.[26][61][62] Balista's victory was only partial, as Shapur withdrew east of Cilicia, where the marauding Persian units continued to occupy the area,[63] while a Persian force took advantage of Balista's return to Syria and headed further west into Anatolia.[61]

Reign

According to the Augustan History, Odaenathus was declared king of Palmyra as soon as the news of the Roman defeat at Edessa reached the city.[64] It is not known if Odaenathus contacted Fulvius Macrianus and there is no evidence that he took orders from him.[65]

Early Persian war and Syria

Odaenathus assembled the Palmyrene army and Syrian peasants then marched north to meet the Persian emperor, who was withdrawing home.[note 11][52][65] The Palmyrene monarch fell upon the retreating Shapur at a place between Samosata and Zeugma west of the Euphrates in late summer 260.[65][66] Odaenathus defeated the Persians, expelling Shapur from the province of Syria.[65] In the beginning of 261, Fulvius Macrianus headed to Europe accompanied by Macrianus Minor, leaving Quietus and Balista in Emesa.[65] Odaenathus' whereabouts during this episode are not clear; he could have distributed the army in garrisons along the frontier or might have brought it back to his capital.[53] The Palmyrene monarch seems to have waited until the situation clarified, declaring loyalty neither to Fulvius Macrianus nor to Gallienus.[53] In the spring of 261, Fulvius Macrianus arrived in the Balkans but was defeated and killed along with Macrianus Minor; Odaenathus then marched on Emesa, where Quietus and Balista were staying.[53] The Emesans killed Quietus as Odaenathus approached the city,[53] while Balista was captured and executed by the king in autumn 261.[57][67]

Ruler of the East

The elimination of the usurpers left Odaenathus as the most powerful leader in the Roman east;[53] he was granted many titles by the emperor but those honors are debated among scholars:[68]

- Dux Romanorum (commander of the Romans): was probably given to Odaenathus to recognize his position as the commander in chief of the forces in the east against the Persians; it was inherited by Odaenathus' son and successor Vaballathus.[69]

- Corrector totius orientis (Righter of the entire East):[32] it is generally accepted by modern scholars that he bore this title.[70] The corrector had an overall command of the Roman armies and authority over the Roman provincial governors in the designated region.[71][72] There are no known attestations of the title during Odaenathus' lifetime.[70] Evidence for the king bearing the title consists of two inscriptions in Palmyrene dialect: one posthumous dedication describing him as MTQNNʿ of the East (derived from the Aramaic root TQN, meaning to set in order), and the other describing his heir Vaballathus with the same title, albeit using the word PNRTTʿ instead of MTQNNʿ.[71][73]

- However, the sort of authority accorded by this position is widely discussed.[71] The problem arises from the word MTQNNʿ; its exact meaning is debated.[73] The word is translated into Latin as "corrector", but "restitutor" is another possible translation; the latter title was an honorary one meant to praise the bearer for driving enemies out of Roman territories.[73] However, the inscription of Vaballathus is clearer, as the word PNRTTʿ is not a Palmyrene word but a direct Palmyrene translation of the Greek term Epanorthotes, which is usually an equivalent to corrector.[73]

- According to David Potter, Vaballathus inherited his father's exact titles.[71] Hartmann points out that there have been cases where a Greek word was translated directly to Palmyrene and a Palmyrene equivalent was also used to mean the same thing.[73] The dedication to Odaenathus would be the use of a Palmyrene equivalent, while the inscription of Vaballathus would be the direct translation.[71] Despite all the arguments, it cannot be certain that Odaenathus was a corrector.[73]

- Imperator totius orientis (commander-in-chief of the entire East): only the Augustan History claims that Odaenathus was conferred this title; the same source also claims that he was made an Augustus (co-emperor) following his defeat of the Persians.[68] Both claims are dismissed by scholars.[68] Odaenathus seems to have been acclaimed as Imperator by his troops, which is a salutation reserved for the Roman emperor; this acclamation might explain the erroneous reports of the Augustan History.[74]

Regardless of the titles, Odaenathus controlled the Roman East with the approval of Gallienus, who could do little but to formalize Odaenathus' self-achieved status and settle for his formal loyalty.[note 12][75][72][76] Palmyra itself, although officially still part of the Roman Empire, became a de facto allied state to Rome instead of a provincial city.[55] Outside of Palmyra, Odaenathus' authority extended from the Pontic coast in the north to Palestine in the south.[77] This area included the Roman provinces of Syria, Phoenice, Palaestina, Arabia, Anatolia's eastern regions and later (following the campaign of 262) Osroene and Mesopotamia.[77][78][79]

First Persian campaign 262

Perhaps driven by the will to take revenge for the destruction of Palmyrene trade centers and discourage Shapur from initiating future attacks, Odaenathus launched an invasion against the Persians.[80] In the spring of 262, the king marched north into the occupied Roman province of Mesopotamia, driving out the Persian garrisons and freeing Edessa and Carrhae.[81][82] The first onslaught was aimed at Nisibis, which Odaenathus regained but sacked since the inhabitants were sympathetic toward the Persian occupation.[82] The Palmyrene monarch destroyed the Jewish city of Nehardea, 45 km west of the Persian capital Ctesiphon,[note 13][86] as he deemed the Jews of Mesopotamia loyal to Shapur.[87] By late 262 or early 263, Odaenathus stood at the walls of the Persian capital.[88]

The exact route taken by Odaenathus from Palmyra to Ctesiphon remains uncertain; it is probably similar to the route emperor Julian took in 363 during his campaign against Persia.[89] Using this route, Odaenathus would have crossed the Euphrates at Zeugma then moved east to Edessa followed by Carrhae then Nisibis; here, he would have descended south along the Khabur River to the Euphrates valley and marched alongside the river's left bank to Nehardea.[89] After taking the city, he penetrated the Sassanian province of Asōristān and marched along the royal canal Naarmalcha towards the Tigris where the Persian capital stood.[89]

Once at Ctesiphon, Odaenathus immediately began the siege of the well-fortified winter residence of the Persian kings; severe damage was inflicted upon the surrounding areas due to the battles with Persian troops.[88] The city held its ground and the logistical problems of fighting in enemy territory probably prompted the Palmyrenes to lift the siege.[88] Odaenathus headed north along the Euphrates carrying with him numerous prisoners and booty.[88] The invasion resulted in the full restoration of the Roman lands (viz., the Osroene and Mesopotamia provinces) occupied by Shapur since the beginning of his invasions in 252.[note 14][78][91] However, Dura-Europus and other Palmyrene posts south of Circesium, such as Anah, were not rebuilt.[81] Odaenathus sent the captives to Rome and by the end of 263, Gallienus added Persicus Maximus ("The great victor in Persia") to his titles and held a triumph.[92]

King of Kings

In 263, after his return, Odaenathus assumed the title King of Kings of the East (Mlk Mlk),[note 15] and headed to Antioch, the traditional capital of Syria, where he crowned his son Hairan I as co-King of Kings.[note 16][95][98] The title was a symbol of legitimacy in the East, starting with the Assyrians, then the Achaemenids, who used it to symbolize their supremacy over all other rulers, and was adopted by the Parthian monarchs following their defeat of the Seleucids to legitimize their conquests.[99] The first Sassanian monarch Ardashir I adopted the title following his victory over the Parthians.[100] Odaenathus' son was crowned with a diadem and a tiara; the choice of the location was probably meant to express that the Palmyrene monarchs were now the successors of the Seleucid and Iranian rulers who controlled Syria and Mesopotamia in the past.[98]

Relation with Rome

In the Roman Empire's hierarchical system, a vassal king using the title of King of Kings did not indicate that he was a peer of the emperor or that the vassalage ties were cut.[101] The title was probably a challenge not to the Roman emperor but to Shapur I; Odaenathus was declaring that he, not the Persian monarch, was the legitimate King of Kings in the East.[75] A lead token depicting Hairan I shows him wearing a crown shaped like that of the Parthian monarchs, so it must have been Odaenathus' crown;[102] this combination of title and imagery indicates that Odaenathus considered himself the rival of the Sassanians and the protector of the region against them.[103]

Odaenathus' intentions are questioned by some historians, such as Drinkwater, who attributed the attempted negotiations with Shapur to Odaenathus' quest for power.[49] However, in contrast to the norm of his period when powerful generals proclaimed themselves emperors, Odaenathus chose not to usurp Gallienus' throne,[104] and minted no coins bearing his own image.[note 17][71] The king had total control over Palmyra and effective control over the Roman East where his military authority was absolute.[75][107] Odaenathus respected Gallienus' privilege to appoint provincial governors,[107] but dealt swiftly with opposition; the Anonymus post Dionem mentions the story of Kyrinus (Quirinus), a Roman official, who showed dissatisfaction with Odaenathus' authority over the Persian frontier and was immediately executed by the king.[note 18][108][110][109]

In general, Odaenathus' actions were connected to his and Palmyra's interests only; his support of Gallienus and his Roman titles did not hide the Palmyrene base of his power and the local origin of his armies, as with his decision not to wait for the emperor to help in 260.[55][74] Odaenathus' status seems to have been, as Watson puts it, "something between powerful subject, independent vassal king and rival emperor".[74]

Administration

Odaenathus behaved as a sovereign monarch;[111] outside his kingdom, he had an overall administrative and military authority over the provincial governors of the Roman eastern provinces.[112] Inside Palmyra, no Roman provincial official had any authority; the king filled the government with Palmyrene staffs.[113] In parallel to the Iranian practice of making the government appear as a family enterprise, Odaenathus bestowed his own gentilicium (Septimius) upon his leading generals and officials such as Zabdas, Zabbai and Worod.[note 19][113]

The Palmyrene constitutional institutions continued to function normally during Odaenathus' reign;[71] he maintained most civic establishments,[37][115] permitting the election of magistrates until 264.[39] When Odaenathus was on campaign, the kingdom was administered by a viceroy, Septimius Worod.[116]

Second Persian campaign 266

Sources are silent regarding the events following the first Persian campaign but the silence in itself is an indication of the peace that prevailed and that the Persians stopped being a threat to the Roman East.[117] The evidence for the second campaign is meager; Zosimus is the only one to mention it specifically.[118] A passage in the Sibylline Oracles is interpreted by Hartmann as an indication of the second invasion.[119] The campaign took place in 266 or 267 and was aimed directly at Ctesiphon;[52] Odaenathus reached the walls of the Persian capital but had to cancel the siege and march north to face the influx of Germanic riders attacking Anatolia.[118][120]

Anatolian campaign

The Romans used the designation "Scythian" to denote many tribes regardless of ethnic origin and sometimes the term would be interchangeable with Goths; the tribes attacking Anatolia were probably the Heruli who built ships to cross the Black Sea in 267 and ravaged the coasts of Bithynia-Pontus, besieging Heraclea Pontica.[118] According to Syncellus, Odaenathus arrived at Anatolia with Hairan I and headed to Heraclea but the riders were already gone.[118] They loaded the spoils onto their ships but many perished in a sea battle probably conducted by Odaenathus; another possibility is that they were shipwrecked.[118]

Assassination

Odaenathus was assassinated along with Hairan I in late 267; the date is debated and some scholars propose 266 or 268, but Vaballathus dated his first year of reign between August 267 and August 268, making late 267 the most probable date.[121] The assassination took place either in Anatolia, or in Syria;[122][123] there is no consensus on the manner, perpetrator or the motive behind the act.[122]

- According to Syncellus, Odaenathus was assassinated near Heraclea Pontica trying to quell a tribal incursion into Pontus;[121] he gives the name of the assassin as another Odaenathus who may or may not have been a relative of the king.[122] The assassin was killed by the king's bodyguard.[124] Hartmann supports the theory that Odaenathus was killed in Pontus.[122]

- Zosimus simply mentions that Odaenathus was killed by conspirators near Emesa at a friend's birthday party without naming the killer.[125][126] Zonaras attributes the crime to a nephew of Odaenathus but does not give a name.[127][128]

- The Augustan History claims that a cousin of the king named Maeonius killed him,[129] while the Anonymus post Dionem names the assassin as another Odaenathus.[128]

Burial

The stone block found in the Temple of Bel bearing Odaenathus' sepulchral inscription was brought from the tomb built by him; this shrine's location is unknown.[20] At the western end of the Great Colonnade at Palmyra, a shrine designated the "Funerary Temple no. 86" (also known as the House Tomb) is located.[130][131] Inside its chamber, steps lead down to a vault crypt which is now lost.[131][132] This mausoleum might have belonged to the royal family, being the only tomb inside the city's walls.[133]

Assassination theories

- Roman conspiracy: John Antiochenus accuses Gallienus of the assassination.[125] An interesting passage in the work of the Anonymus post Dionem speaks of a certain "Rufinus" who orchestrated the assassination on his own initiative then explained his act to the emperor who condoned the crime.[122] This story talks about Rufinus ordering the murder of an older Odaenathus out of fear that he would rebel, and has the younger Odaenathus complaining to the emperor.[note 20][125] Since the older Odaenathus (Odaenathus I) was proved to be a fictional character, the story was neglected by most scholars.[135] However, according to Theodor Mommsen, younger Odaenathus is an oblique reference to Vaballathus;[136] Rufinus should be identified with Cocceius Rufinus, the Roman governor of Arabia between 261/262.[135] The evidence for a Roman conspiracy is very weak and can not be confirmed.[135]

- Family feud: According to Zonaras, Odaenathus' nephew misbehaved during a lion hunt;[127] he made the first attack and killed the animal to the dismay of the king.[124] Odaenathus warned the nephew who ignored the warning and repeated the act twice causing the king to deprive him of his horse, a great insult in the East.[124][137] The nephew threatened Odaenathus and was put in chains as a result; Hairan I asked his father to forgive his cousin and his request was granted but as the king was drinking, the nephew approached him with a sword and killed him along with Hairan I.[124] The bodyguard immediately executed the nephew.[124]

- Zenobia: the wife of Odaenathus was accused by the Augustan History of having formerly conspired with Maeonius, as Hairan I was her stepson and she could not accept that he was the heir to her husband instead of her own children.[125] However, there is no suggestion in the Augustan History that Zenobia was involved in the event that saw her husband's murder;[137] the act is attributed to Maeonius' degeneracy and jealousy.[125] Those accounts by the Augustan History can be dismissed as fiction.[138] The hints in modern scholarship that Zenobia had a hand in the assassination out of her desire to rule the empire and dismay with her husband's pro-Roman policy can be dismissed as there was no reversal of that policy during the first years following Odaenathus' death.[122]

- Persian agents or Palmyrene traitors: the possibility of a Persian involvement exists but the outcome of the assassination would not have served Shapur without establishing a pro-Persian monarch on the Palmyrene throne.[139] Another possibility would be Palmyrenes dissatisfied with Odaenathus' reign and the changes of their city's governmental system.[137]

Personal life and succession

Odaenathus was married twice; nothing is known about his first wife's name or fate.[140] Zenobia was the king's second wife, whom he married in the late 250s when she was 17 or 18 years old.[141]

The number of children Odaenathus had with his first wife is unknown and only one is attested:

- Hairan I: the name appears on a 251 inscription from Palmyra describing him as Ras, implying that he was already an adult by then.[140] In the Augustan History, Odaenathus' eldest son is named Herod; the inscription at Palmyra dating to 263 celebrating Hairan's coronation mentions him with the name Herodianus.[140] It is possible that the Hairan of the 251 inscription is not the same as the Herodianus of the one from 263,[140] but this is contested by Hartmann, who concludes that the reason for the difference in the spelling is the language used in the inscription (Herodianus being the Greek version),[138] meaning that Odaenathus' eldest son and co-king was Hairan Herodianus.[142]

The children of Odaenathus and Zenobia are:

- Vaballathus: he is attested on several coins, inscriptions, and in the ancient literature.[143]

- Hairan II: his image appears on a seal impression along with his older brother Vaballathus; his identity is much debated.[143] Potter suggests that he is the same as Herodianus, who was crowned in 263, and that the Hairan I mentioned in 251 died before the birth of Hairan II.[144]

- Herennianus and Timolaus: the two were mentioned in the Augustan History and are not attested in any other source;[143] Herennianus might be a conflation of Hairan and Herodianus while Timolaus is most probably a fabrication,[138] although Dietmar Kienast suggests that he might be Vaballathus.[145]

Possible descendants of Odaenathus living in later centuries are reported: "Lucia Septimia Patabiniana Balbilla Tyria Nepotilla Odaenathiana" is known through a dedication dating to the late third or early fourth century inscribed on a tombstone erected by a wet nurse to her "sweetest and most loving mistress".[146] The tombstone was found in Rome at the San Callisto in Trastevere.[147] Another possible relative is "Eusebius" who is mentioned by Libanius in 391 as a son of an "Odaenathus" who was in turn a descendant of the king;[148] the father of Eusebius is mentioned as fighting against the Persians (most probably in the ranks of emperor Julian).[149] In 393, Libanius mentioned that Eusebius promised him a speech written by Longinus for the king.[148] In the fifth century, the philosopher "Syrian Odaenathus" lived in Athens and was a student of Plutarch of Athens;[150] he might have been a distant descendant of the king.[151]

Succession: the Augustan History claims that Maeonius was proclaimed emperor for a brief period before being killed by the soldiers.[122][135][137] However, no inscriptions or other evidence exist for Maeonius' reign and he was probably killed immediately after assassinating the king.[152] Odaenathus was succeeded by his son, the ten-year-old Vaballathus, under the regency of Zenobia.[153] Hairan II probably died soon after his father,[154] as only Vaballathus succeeded to the throne.[155]

Legacy

| “ | Odaenathus, the mention of whose name alone caused the hearts of the Persians to falter. Everywhere victorious, he liberated the cities and the territories belonging to each of them and made the enemies place their salvation in their prayers rather than in the force of arms. | ” |

| — Libanius, on the exploits of Odaenathus.[148] | ||

Odaenathus was the founder of the Palmyrene royal dynasty;[156] he left Palmyra the premier power in the East,[157] and his actions laid the foundation of Palmyrene strength which culminated in the establishment of the Palmyrene Empire in 270.[50] No images of Odaenathus have been discovered, hence, there is no information about his appearance;[158] few sculpted heads from Palmyra were identified by scholars as representing Odaenathus based on their monumentality and regal style, but those sculptures lack any inscriptions to help identifying the man they represent beyond doubt.[159]

Many writers wrote about the deeds of Odaenathus; Nicostratus of Trebizond probably accompanied the king on his campaigns and wrote a history of that period starting from Philip the Arab and ending shortly before the king's death.[160] According to Potter, Nicostratus' account was meant to glorify Odaenathus and demonstrate his superiority over Roman emperors.[161]

The memory of Odaenathus was highly esteemed in the Roman Empire; the Augustan History, written in the fourth century, places Odaenathus among the Thirty Tyrants (probably because he assumed the title of king).[162] However, it speaks highly of his role in the Persian war and credits him with saving the empire: "Had not Odaenathus, prince of the Palmyrenes, seized the imperial power after the capture of Valerian when the strength of the Roman state was exhausted, all would have been lost in the East".[163]

The king was praised by Libanius,[164] and was the subject of a prophecy in the Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle:[note 21] "Then shall come one who was sent by the sun [i.e., Odaenathus], a mighty and fearful lion, breathing much flame. Then he with much shameless daring will destroy ... the greatest beast — venomous, fearful and emitting a great deal of hisses [i.e., Shapur]".[166]

Odaenathus is viewed negatively in Rabbinic sources;[note 22] his sack of Nehardea mortified the Jews,[167] and he was cursed by the Babylonian Jews and the Jews of Palestine.[78]

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Odaenathus of Palmyra | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ Hairan could also be of Aramaic etymology.[2][3]

- ↑ Palmyrene caravan patrons owned the land on which the caravan animals were raised, providing animals and guards for the merchants who led the caravans.[9]

- ↑ The 220 date is proposed by Michael Gawlikowski, head of the Polish archaeological expedition in Palmyra; Ernest Will, however, maintains that the king was born c. 200.[13]

- ↑ This assumption was facilitated by a passage in the work of Anonymus post Dionem which speaks about a younger Odaenathus asking the Roman emperor to punish his official Rufinus for the latter's role in assassinating an elder Odaenathus.[22] For information see Assassination of Odaenathus theories: Roman conspiracy.

- ↑ William Waddington considered king Odaenathus the son of Ras Hairan while Theodor Mommsen considered the latter an older brother of the king.[25]

- ↑ Although the first known inscription attesting Odaenathus' title dates to 252, it is confirmed that he rose to the position at least one year earlier, based on Hairan I's attestation as Ras in 251.[35]

- ↑ There are two temples of Bel in Dura-Europos; the first was established by the Palmyrenes in the early first century outside the city wall in the necropolis and the second (depicted in this picture, also named "the temple of the Palmyrene gods") was administered by Palmyrenes only in the third century.[43]

- ↑ Hermann Schiller denied Odaenathus was a governor of Phoenice; the (ὁ λαμπρότατος ὑπατικός) title was also attested in Palmyra for different notables and it could have been an honorary title of high degree.[25]

- ↑ There is no proof that Shapur entered the central areas of northern Syria; he seems to have moved directly west deep into Cilicia.[58]

- ↑ At first Fulvius Macrianus showed loyalty to Gallienus.[61]

- ↑ No evidence exists, but Odaenathus might have had some Roman units in his ranks considering that he was fighting in the vicinity of Roman legionary bases; those troops might have been loyal to Gallienus and thus chose to join Odaenathus.[53] Whether Roman soldiers fought under Odaenathus or not is a matter of speculation.[53]

- ↑ The Roman East traditionally included all the Roman lands in Asia east of the Bosphorus.[16]

- ↑ Lukas De Blois proposes that Odaenathus actually destroyed Nehardea in 259 in support of Valerian.[83] In the work of Sherira Gaon named "Iggeret Rav Sherira Gaon", the destruction date is given as 570 (Seleucid), corresponding to 259 AD.[84] However, Jacob Neusner believes that the right date is 262 or 263.[85]

- ↑ Contrary to the account of the Augustan History, there is no proof that Odaenathus occupied Armenia.[90]

- ↑ Odaenathus' title as it appears in Palmyrene inscriptions was King of Kings and corrector of the East.[93]

- ↑ 1- The evidence for crowning Hairan I is a dedication found inscribed on a statue base from Palmyra which is undated.[57] However, the dedication was made by Septimius Worod as the duumviri of Palmyra, an office occupied by Worod between 263 and 264. Hence, the coronation took place c. 263.[94]

2- An undated inscription, written in Greek and difficult to decipher, found on a stone reused in the Palmyrene Camp of Diocletian, addresses Odaenathus as King of Kings (Rex Regum) and was probably set during his reign.[95] However, firmly dated inscriptions attesting Odaenathus with the title are made after his death including one that was set in 271.[27][52] Although undisputed evidence for the use of the title by Odaenathus during his lifetime is lacking, Hairan I, his son, who died with him,[96] is directly attested as "King of Kings" during his lifetime, and it is highly unlikely that Odaenathus was simply a king while his son was the King of Kings.[97] - ↑ Hubertus Goltzius forged coins of Odaenathus in the 16th century;[105] according to Joseph Hilarius Eckhel "The coins of Odenathus are known only to Goltzius; and if any one will put faith in their existence, let him go to the fountain head (i.e. Goltzius)".[106] According to the Augustan History, Gallienus minted a coin in honor of Odaenathus where he was depicted taking the Persians captive; the existence of this coin is doubtful.[106]

- ↑ No information on the identity of Kyrinus exists;[108] it is possible that he is the same as Aurelius Quirinius, who is recorded as head of the financial administration of Egypt in 262.[109]

- ↑ This gentilicium was exclusive to the family of Odaenathus prior to the 260s.[114]

- ↑ This story gave rise to the now-discounted assumption that Odaenathus I existed.[134]

- ↑ The Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle is compiled by an oracle who collected a series of earlier texts in chronological order; it is dated to c. 263.[165]

- ↑ He is named "Papa ben Nasor" (Papa son of Nasor) in the sources.[86]

References

Citations

- ↑ Kropp 2013, p. 225.

- 1 2 3 Powers 2010, p. 130.

- ↑ Stoneman 1994, p. 77.

- ↑ Stark 1971, p. 65, xx, 85.

- 1 2 3 4 Teixidor 2005, p. 195.

- ↑ Gawlikowski 1985, p. 260.

- 1 2 Fried 2014, p. 95.

- 1 2 Ball 2002, p. 77.

- ↑ Howard 2012, p. 159.

- ↑ Smith II 2013, p. 154.

- ↑ Drijvers 1980, p. 67.

- ↑ Brown 1936, p. 257.

- ↑ Hartmann 2008, p. 348.

- ↑ Powers 2010, p. 130.

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 61.

- 1 2 Ball 2002, p. 6.

- ↑ Matyszak 2004, p. 246.

- ↑ Shahîd 1995, p. 296.

- ↑ Matyszak & Berry 2008, p. 244.

- 1 2 Addison 1838, p. 166.

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 59.

- 1 2 Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 314.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sartre 2005, p. 512.

- 1 2 Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 60.

- 1 2 3 4 Harrer 1915, p. 59.

- 1 2 Watson 2004, p. 29.

- 1 2 Stoneman 1994, p. 78.

- ↑ Sartre. 2005, p. 352.

- ↑ Edwell 2007, p. 27.

- ↑ Ball 2002, p. 76.

- ↑ Edwell 2007, p. 34.

- 1 2 Goldsworthy 2009, p. 62.

- ↑ Young 2003, p. 209.

- 1 2 3 4 Southern 2008, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Southern 2008, p. 44.

- ↑ Mackay 2004, p. 272.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith II 2013, p. 131.

- ↑ Mennen 2011, p. 224.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 43.

- ↑ Potter 2010, p. 160.

- 1 2 Watson 2004, p. 30.

- 1 2 Young 2003, p. 210.

- 1 2 Dirven 1999, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 179.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 99.

- ↑ Millar 1993, p. 159.

- ↑ Edwell 2007, p. 185.

- 1 2 3 Klijn 1999, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 4 Southern 2008, p. 182.

- 1 2 3 Dignas & Winter 2007, p. 158.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith II 2013, p. 177.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Southern 2008, p. 60.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 Young 2003, p. 159.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Southern 2008, p. 48.

- 1 2 3 Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 77.

- 1 2 Millar 1993, p. 166.

- ↑ Ando 2012, p. 167.

- ↑ Dignas & Winter 2007, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Drinkwater 2005, p. 44.

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 57.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 58.

- ↑ Dignas & Winter 2007, p. 159.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Southern 2008, p. 59.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 144.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 144, 145.

- 1 2 3 Bryce 2014, p. 290.

- ↑ Bryce 2014, p. 291.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Young 2003, p. 215.

- 1 2 Goldsworthy 2009, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Southern 2008, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 Watson 2004, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 Young 2003, p. 214.

- ↑ Vervaet 2007, p. 137.

- 1 2 Dignas & Winter 2007, p. 160.

- 1 2 3 Avner 1996, p. 333.

- ↑ De Blois 1976, p. 35.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 70.

- 1 2 Hartmann 2001, p. 173.

- 1 2 Hartmann 2001, p. 168.

- ↑ De Blois 1976, p. 2.

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 70.

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 370.

- 1 2 Hartmann 2001, p. 169.

- ↑ Dubnov 1968, p. 151.

- 1 2 3 4 Hartmann 2001, p. 172.

- 1 2 3 Hartmann 2001, p. 171.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 174.

- ↑ De Blois 1976, p. 3.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 71.

- ↑ Butcher 2003, p. 60.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 178.

- 1 2 Hartmann 2001, p. 176.

- ↑ Teixidor 2005, p. 198.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 72.

- 1 2 Andrade 2013, p. 333.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 180.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 181.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 182.

- ↑ Potter 2014, p. 256.

- ↑ Potter 2010, p. 162.

- ↑ Mommsen 2005, p. 298.

- ↑ Clinton 2010, p. 63.

- 1 2 Stevenson 1889, p. 583.

- 1 2 Ando 2012, p. 171.

- 1 2 Hartmann 2001, p. 156.

- 1 2 Alföldi 1939, p. 176.

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 66.

- ↑ Sartre 2005, p. 514.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 75.

- 1 2 Potter 2014, p. 257.

- ↑ Millar 1971, p. 9.

- ↑ Sivertsev 2002, p. 72.

- ↑ Cooke 1903, p. 286.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 73.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Southern 2008, p. 76.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 183.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 216.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Southern 2008, p. 78.

- ↑ Ando 2012, p. 172.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 71.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 220.

- 1 2 Potter 2014, p. 259.

- 1 2 Potter 2014, p. 629.

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 70.

- ↑ Gawlikowski 2005, p. 55.

- 1 2 Casule 2008, p. 103.

- ↑ Darke 2006, p. 238.

- ↑ Stoneman 1994, p. 67.

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 314, 315.

- 1 2 3 4 Stoneman 1994, p. 108.

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 316.

- 1 2 3 4 Bryce 2014, p. 292.

- 1 2 3 Watson 2004, p. 58.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 79.

- 1 2 3 4 Southern 2008, p. 8.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 4.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 10.

- ↑ Potter 2014, p. 628.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 174.

- ↑ Stoneman 1994, p. 187.

- ↑ Lanciani 1909, p. 169.

- 1 2 3 Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 110.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 415.

- ↑ Curnow 2011, p. 199.

- ↑ Traina 2011, p. 47.

- ↑ Brauer 1975, p. 163.

- ↑ Bryce 2014, p. 299.

- ↑ Stoneman 1994, p. 115.

- ↑ Southern 2015, p. 150.

- ↑ Sahner 2014, p. 133.

- ↑ Young 2003, p. 163.

- ↑ Wadeson 2014, p. 49.

- ↑ Wadeson 2014, p. 54.

- ↑ Teixidor 2005, p. 205.

- ↑ Teixidor 2005, p. 206.

- ↑ Gibbon 1906, p. 352.

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 74.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 200.

- ↑ Potter 2014, p. 229.

- ↑ Kaizer 2009, p. 185.

- ↑ Teixidor 2005, p. 209.

Sources

- Addison, Charles Greenstreet (1838). Damascus and Palmyra: a journey to the East. 2. Richard Bentley. OCLC 833460514.

- Alföldi, Andreas (1939). "The Crisis of the Empire". In Cook, Stanley Arthur; Adcock, Frank Ezra; Charlesworth, Martin Percival; Baynes, Norman Hepburn. The Imperial Crisis and Recovery AD 193–324. The Cambridge Ancient History (First Series). 12. Cambridge University Press. OCLC 654926028.

- Ando, Clifford (2012). Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284: The Critical Century. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-5534-2.

- Andrade, Nathanael J. (2013). Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01205-9.

- Ball, Warwick (2002). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-82387-1.

- Brauer, George C. (1975). The Age of the Soldier Emperors: Imperial Rome, A.D. 244-284. Noyes Press. ISBN 978-0-8155-5036-5.

- Brown, Frank Edward (1936). "H, Block 1. The Temple of the Gaddé". In Rostovtzeff, Mikhail Ivanovich; Brown, Frank Edward; Welles, Charles Bradford. The Excavations at Dura-Europos. Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Preliminary Report on the Seventh and Eighth Seasons of Work, 1933–1934 and 1934–1935. Yale University Press. OCLC 491287768.

- Bryce, Trevor (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-100292-2.

- Butcher, Kevin (2003). Roman Syria and the Near East. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-715-3.

- Casule, Francesca (2008). Art and History: Syria. Translated by Boomsliter, Paula Elise; Dunbar, Richard. Casa Editrice Bonechi. ISBN 978-88-476-0119-2.

- Clinton, Henry Fynes (2010) [1850]. Fasti Romani: From the Death of Augustus to the Death of Heraclius. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-01248-5.

- Cooke, George Albert (1903). A Text-Book of North-Semitic Inscriptions: Moabite, Hebrew, Phoenician, Aramaic, Nabataean, Palmyrene, Jewish. The Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-5-87188-785-1.

- Curnow, Trevor (2011) [2006]. The Philosophers of the Ancient World: An A-Z Guide. Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 978-1-84966-769-2.

- Darke, Diana (2006). Syria. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-162-3.

- De Blois, Lukas (1976). The Policy of the Emperor Gallienus. Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society: Studies of the Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society. 7. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04508-8.

- Dignas, Beate; Winter, Engelbert (2007) [2001]. Rome and Persia in Late Antiquity: Neighbours and Rivals. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84925-8.

- Dirven, Lucinda (1999). The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World. 138. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11589-7. ISSN 0927-7633.

- Dodgeon, Michael H; Lieu, Samuel N. C (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars AD 226-363: A Documentary History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-96113-9.

- Drijvers, Hendrik Jan Willem (1980). Cults and Beliefs at Edessa. Études préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l'Empire romain. 82. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-06050-0.

- Drinkwater, John (2005). "Maximinus to Diocletian and the 'crisis'". In Bowman, Alan K.; Garnsey, Peter; Cameron, Averil. The Crisis of Empire, AD 193-337. The Cambridge Ancient History (Second Revised Series). 12. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30199-2.

- Dubnov, Simon (1968) [1916]. History of the Jews From the Roman Empire to the Early Medieval Period. 2. Translated by Spiegel, Moshe. Thomas Yoseloff. OCLC 900833618.

- Edwell, Peter (2007). Between Rome and Persia: The Middle Euphrates, Mesopotamia and Palmyra Under Roman Control. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-09573-5.

- Falk, Avner (1996). A Psychoanalytic History of the Jews. Associated University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3660-2.

- Fried, Lisbeth S. (2014). Ezra and the Law in History and Tradition. Studies on Personalities of the Old Testament. 11. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-61117-410-6.

- Gawlikowski, Michal (1985). "Les princes de Palmyre". Syria. Archéologie, Art et Histoire. l'Institut Français du Proche-Orient. 62 (3/4). ISSN 0039-7946.

- Gawlikowski, Michal (2005). "The City of the Dead". In Cussini, Eleonora. A Journey to Palmyra: Collected Essays to Remember Delbert R. Hillers. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12418-9.

- Gibbon, Edward (1906) [1781]. Bury, John Bagnell; Lecky, William Edward Hartpole, eds. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. 2. Fred de Fau & Company. OCLC 630781872.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). The Fall Of The West: The Death Of The Roman Superpower. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-0-297-85760-0.

- Harrer, Gustave Adolphus (2006) [1915]. Studies in the History of the Roman Province of Syria. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59752-463-6.

- Hartmann, Udo (2001). Das palmyrenische Teilreich (in German). Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-07800-9.

- Hartmann, Udo (2008). "Das palmyrenische Teilreich". In Johne, Klaus-Peter; Hartmann, Udo; Gerhardt, Thomas. Die Zeit der Soldatenkaiser: Krise und Transformation des Römischen Reiches im 3. Jahrhundert n. Chr. (235-284) (in German). Akademie Verlag. ISBN 978-3-05-008807-5.

- Howard, Michael C. (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9033-2.

- Kaizer, Ted (2009). "The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires, c. 247 BC - AD 300". In Harrison, Thomas. The Great Empires of the Ancient World. J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 978-0-89236-987-4.

- Klijn, Albertus Frederik Johannes (1999). "6 Ezra 15,28–33 and the Historical Events in the Middle of the Third Century". In Vanstiphout, Herman L. J.; van Bekkum, Wout Jacques; van Gelder, Geert Jan; Reinink, Gerrit Jan. All Those Nations ... Cultural Encounters Within and with the Near East. Comers/Icog Communications. 2. Styx Publications. ISBN 978-90-5693-032-5.

- Kropp, Andreas J. M. (2013). Images and Monuments of Near Eastern Dynasts, 100 BC - AD 100. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967072-7.

- Lanciani, Rodolfo Amedeo (1909). Wanderings in the Roman Campagna. Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 645769.

- Mackay, Christopher S. (2004). Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80918-4.

- Matyszak, Philip (2004). The Enemies of Rome: From Hannibal to Attila the Hun. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-25124-9.

- Matyszak, Philip; Berry, Joanne (2008). Lives of the Romans. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-25144-7.

- Mennen, Inge (2011). Power and Status in the Roman Empire, AD 193-284. Impact of Empire. 12. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-20359-4.

- Millar, Firgus (1971). "Paul of Samosata, Zenobia and Aurelian: the Church, Local Culture and Political Allegiance in Third-Century Syria". Journal of Roman Studies. The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. 61. doi:10.2307/300003. OCLC 58727367.

- Millar, Fergus (1993). The Roman Near East, 31 B.C.-A.D. 337. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-77886-3.

- Mommsen, Theodor (2005) [1882]. Wiedemann, Thomas, ed. A History of Rome Under the Emperors. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-62479-9.

- Potter, David S (2014). The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–395. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-69477-8.

- Potter, David S. (2010). "The Transformation of the Empire: 235–337 CE". In Potter, David S. A Companion to the Roman Empire. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. 32. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-9918-6.

- Powers, David S. (2010). "Demonizing Zenobia: The legend of al-Zabbā in Islamic Sources". In Roxani, Eleni Margariti; Sabra, Adam; Sijpesteijn, Petra. Histories of the Middle East: Studies in Middle Eastern Society, Economy and Law in Honor of A.L. Udovitch. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18427-5.

- Sahner, Christian (2014). Among the Ruins: Syria Past and Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939670-2.

- Sartre, Maurice (2005). "The Arabs and the Desert Peoples". In Bowman, Alan K.; Garnsey, Peter; Cameron, Averil. The Crisis of Empire, AD 193-337. The Cambridge Ancient History. 12. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30199-2.

- Sartre., Maurice (2005). The Middle East Under Rome. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01683-5.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century (Part1: Political and Military History). 1. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 978-0-88402-214-5.

- Sivertsev, Alexei (2002). Private Households and Public Politics in 3rd-5th Century Jewish Palestine. Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism. 90. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-147780-5.

- Smith II, Andrew M. (2013). Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-986110-1.

- Southern, Patricia (2008). Empress Zenobia: Palmyra's Rebel Queen. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4411-4248-1.

- Southern, Patricia (2015). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-49694-6.

- Stark, Jürgen Kurt (1971). Personal Names in Palmyrene Inscriptions. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-198-15443-3.

- Stevenson, Seth William (1889). Smith, Charles Roach; Madden, Frederic William, eds. A Dictionary of Roman Coins, Republican and Imperial. George Bell and Sons. OCLC 504705058.

- Stoneman, Richard (1994). Palmyra and Its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt Against Rome. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08315-2.

- Teixidor, Javier (2005). "Palmyra in the third century". In Cussini, Eleonora. A Journey to Palmyra: Collected Essays to Remember Delbert R. Hillers. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12418-9.

- Traina, Giusto (2011) [2007]. 428 AD: An Ordinary Year at the End of the Roman Empire. Translated by Cameron, Allan (4 ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3286-6.

- Vervaet, Frederik J. (2007). "The reappearance of the supra-provincial commands in the late second and early third centuries C.E.: Constitutional and historical considerations". In Hekster, Olivier; De Kleijn, Gerda; Slootjes, Daniëlle. Crises and the Roman Empire: Proceedings of the Seventh Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire, Nijmegen, June 20-24, 2006. Impact of Empire. 7. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16050-7.

- Wadeson, Lucy (2014). "Funerary Portrait Of A Palmyrene Priest". In Flood, Derene. Records of the Canterbury Museum. 28. Canterbury Museum. ISSN 0370-3878.

- Watson, Alaric (2004) [1999]. Aurelian and the Third Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-90815-8.

- Young, Gary K. (2003) [2001]. Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy 31 BC - AD 305. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-54793-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Odaenathus. |

- Panoramic pictures of Odaenathus' possible mausoleum (The Funerary Temple nr. 86)

- Odaenathus' passage in Encyclopædia Britannica

Odaenathus House of Odaenathus Born: 220 Died: 267 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by New title |

King of Kings of the East 263–267 with Hairan I as junior King of Kings (263–267) |

Succeeded by Vaballathus |

| King of Palmyra 260–267 | ||

| Ras of Palmyra 240s–260 with Hairan I (?-260) |

Title obsolete Became king | |