Qibla

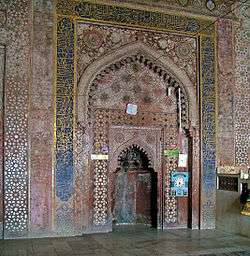

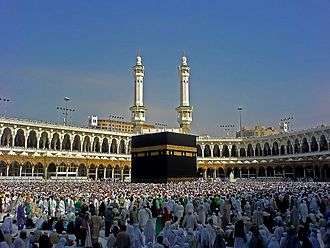

The Qibla (Arabic: قِـبْـلَـة, "Direction", also transliterated as Qiblah, Qibleh, Kiblah, Kıble or Kibla), is the direction that should be faced when a Muslim prays during Ṣalāṫ (Arabic: صَـلَاة). It is fixed as the direction of the Kaaba in the Hejazi[2] city of Mecca. Most mosques contain a wall niche that indicates the Qiblah, which is known as a miḥrâb (Arabic: مِـحْـرَاب). Most multifaith prayer rooms will also contain a Qibla, although usually less standardized in appearance than one would find within a mosque.[3]

Muslims all praying towards the same point is traditionally considered to symbolize the unity of the Ummah (Arabic: اُمَّـة, the community Muslims worldwide), under the Sharī‘ah (Arabic: شَـرِيْـعَـة, Law of God). The Qiblah also has importance beyond Salah, and plays a part in various ceremonies. The head of an animal that is slaughtered using Ḥalāl (Arabic: حَـلَال, 'Allowed') methods is usually aligned with the Qiblah. After death, Muslims are usually buried with the body at right angles to the Qibla and the face turned right towards the direction of the Qiblah. Thus, archaeology can indicate an Islamic necropolis, if no other signs are present.

History

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) |

|---|

| Islamic studies |

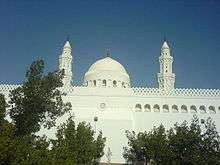

According to the traditional Muslim view, the Qiblah in the Islamic prophet Muhammad's time was originally the Noble Sanctuary in the Shaami city of Jerusalem, similar to Judaism.[1][4] This Qiblah was used for over 13 years, from 610 CE until 623 CE. Seventeen months after Muhammad's 622 CE arrival in Medina – the date is given as 11 February 624 – the Qiblah became oriented towards the Kaaba in Mecca.[5][6] According to traditional accounts from Muhammad's companions, the change happened very suddenly during the noon prayer in Medina, in a mosque now known as Masjid al-Qiblaṫayn (Arabic: مَـسْـجِـد الْـقِـبْـلَـتَـيْـن, "Mosque of the Two Qiblahs").[6] Muhammad was leading the prayer when he received revelations from God instructing him to take the Kaaba as the Qiblah (literally, "Turn then Thy face in the direction of the Sacred Mosque.").[6][7] According to the traditional accounts contained in the hadith and sira, Muhammad, who had been facing Jerusalem, upon receiving this revelation, immediately turned around to face Mecca, and those praying behind him also did so.[6]

Some have claimed that the Qur'an does not identify or allude to Jerusalem as being the first Qiblah, and that the practice of facing Jerusalem is only mentioned in traditional biographies of Muhammad, or hadith collections.[8] There is also disagreement as to when the practice started and for how long it lasted.[8] Some sources say the Jerusalem Qiblah was used for a period of between sixteen and eighteen months.[9] The Jewish custom of facing Jerusalem for prayer may have influenced the Muslim Qiblah.[10] Others surmise that the use of Jerusalem as the direction of prayer was to either induce the Jews of Medina to convert to Islam or to "win over their hearts".[9] When relations with the Jews soured, Muhammad changed the Qiblah towards Mecca.[10] Another reason given why the Qiblah was changed is that Jews viewed the use of Jerusalem as signalling the Muslims' intention of joining their religion. It was changed to discredit this assumption.[9] Others state that it was changed because Muhammad was angered by that city or its people, and not because of his conflict with the Jews.

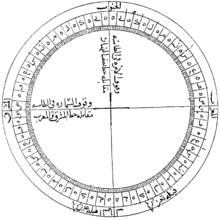

In Medieval times, Muslims travelling abroad used an astrolabe to find the Qiblah.[11]

Determinations

From whencesoever Thou startest forth, turn Thy face in the direction of the sacred Mosque; that is indeed the truth from the Lord. And Allah is not unmindful of what ye do. So from whencesoever Thou startest forth, turn Thy face in the direction of the sacred Mosque; and wheresoever ye are, Turn your face thither: that there be no ground of dispute against you among the people, except those of them that are bent on wickedness; so fear them not, but fear Me; and that I may complete My favours on you, and ye May (consent to) be guided;

It is not righteousness that ye turn your faces Towards east or West; but it is righteousness- to believe in Allah and the Last Day, and the Angels, and the Book, and the Messengers; to spend of your substance, out of love for Him, for your kin, for orphans, for the needy, for the wayfarer, for those who ask, and for the ransom of slaves; to be steadfast in prayer, and practice regular charity; to fulfil the contracts which ye have made; and to be firm and patient, in pain (or suffering) and adversity, and throughout all periods of panic. Such are the people of truth, the Allah-fearing.

— Qur'an, sura 2 (Al-Baqara), ayah 177[13]

The two moments in each year when the sun is directly overhead the Kaaba, the sun will indicate the direction of Mecca in all countries where it is visible. This happens on May 27 or May 28 at 9:18 GMT and on July 15 or July 16 at 9:27 GMT. Likewise there are two moments in each year when the Sun is directly over the antipodes of the Kaaba. This happens on January 12 or January 13 at 21:29 GMT and on November 28 at 21:09 GMT. On those dates, the direction of shadows in any sunlit place will point directly away from the Qiblah. Because the Earth is almost a sphere, this is almost the same as saying that the Qiblah from a place is the direction in which a bird would start flying in order to get to the Kaaba by the shortest possible way. The antipodes of the Kaaba is in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, in remote southern French Polynesia, some 35 mi (56 km) northeast of Tematangi atoll and 85 mi (137 km) west-northwest of Moruroa atoll.

In contrast to the regular custom, there is a mosque which does not face the Qiblah. It is Cheraman Juma Masjid in the south Indian state of Kerala. Unlike other mosques in the south Indian state, it faces eastwards, instead of westwards to Mecca.[14][15][16]

Islamic mathematics

Determining the direction of the Qiblah was a central issue and a constant generator of a scientific environment during the Islamic Golden Age, one that required both mathematics and observation. Muslim scientists who contributed works to determine the Qiblah direction from any point on the Earth's surface were: Al-Khawarizmi, Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi, Al-Nayrizi, Al-Battani, Abū al-Wafā' Būzjānī, Ibn Yunus, Al-Sijzi, Abu Nasr Mansur, Ibn al-Haytham, Al-Biruni, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Ibn al-Shatir, and Al-Khalili, among others.[18]

The Yemeni Sultan al-Malik al-Ashraf described the use of the compass as a Qibla indicator in the 13th century.[19] In a treatise about astrolabes and sundials, al-Ashraf includes several paragraphs on the construction of a compass bowl (ṭāsa). He then uses the compass to determine the north point, the meridian (khaṭṭ niṣf al-nahār), and the Qibla. This is the first mention of a compass in a medieval Islamic scientific text and its earliest known use as a Qibla indicator, although al-Ashraf did not claim to be the first to use it for this purpose.[17][20]

North American interpretations

In recent years, Muslims from North America have used two rules to determine the direction of the Qiblah. According to spherical calculations, a Muslim praying from Anchorage, Alaska would pray almost due north if determining the Qiblah. However, when one looks at the world on most Mercator map projections, Mecca appears to be southwest of Anchorage. The shortest rhumb line (line of constant bearing) from most points in North America to Mecca will point toward the southeast, but the distance to Mecca along this route on the actual surface of the earth is longer than the great circle route.

There are Muslim communities in North America who face toward the northeast, following the great circle route, and there are Muslim communities in North America who face toward the southeast according to traditional early Islamic methods including sighting the stars, sun, etc.[21]

Most Qiblah-calculating programs (see list below) use the great circle method and place the Qiblah northeast from most points in North America.

From space

In April 2006, Malaysian National Space Agency (Angkasa) sponsored a conference[22] of scientists and religious scholars to address the issue of how the Qiblah should be determined when one is in orbit. The conference concluded that the astronaut should determine the location of the Qiblah "according to [their] capability".[23] There have already been several Muslim astronauts, among them the very first being Prince Sultan bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (1985), the latest being the first Muslim woman in space Anousheh Ansari (2006) and the Malaysian angkasawan (astronaut) Sheikh Muszaphar Shukor (2007).

Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani has stated that one should face the direction of the Earth.[24] This is part of the Malaysian document which recommends that the qibla should be 'based on what is possible' for the astronaut, and can be prioritized this way: 1) The Ka'aba 2) The projection of Ka'aba 3) The Earth 4) Wherever.[25]

See also

- Qibla al-Qudsiyya

- Black Stone

- Craig retroazimuthal projection

- Holy site

- Mizrâḥ, the Jewish equivalent of the Qiblah

- Qiblih, the Bahá'í equivalent

- Praying towards Mecca in space

References

- 1 2 Hartsock, Ralph (2014-08-27). "The temple of Jerusalem: past, present, and future". Jewish Culture and History. 16 (2): 199–201. doi:10.1080/1462169X.2014.953832.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary. 2001. p. 479. ISBN 0 87779 546 0. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- ↑ Hewson, Chris (March 1, 2012). "Multifaith Spaces: Objects". University of Manchester. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ↑ Mustafa Abu Sway, The Holy Land, Jerusalem and Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Qur’an, Sunnah and other Islamic Literary Source (PDF), Central Conference of American Rabbis, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28

- ↑ In the Lands of the Prophet, Time-Life, p. 29

- 1 2 3 4 William Montgomery Watt (7 February 1974). Muhammad: prophet and statesman. Oxford University Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0-19-881078-0. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ↑ Sura 2 (Al-Baqara), ayah 144, Quran 2:144

- 1 2 Tamar Mayer; Suleiman Ali Mourad (2008). Jerusalem: idea and reality. Routledge. p. 87. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 Yohanan Friedmann (2003). Tolerance and coercion in Islam: interfaith relations in the Muslim tradition. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- 1 2 Britannica; Dale Hoiberg; Indu Ramchandani (2000). Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan. p. 224. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ↑ Winterburn, Emily (2005). "Using an Astrolabe". muslimheritage.com. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ↑ Quran 2:149–150 (Yusuf Ali)

- ↑ Quran 2:177 (Yusuf Ali)

- ↑ "World's second oldest mosque is in India". Bahrain tribune. Archived from the original on 2006-07-06.

- ↑ Cheraman Juma Masjid A Secular Heritage

- ↑ A mosque from a Hindu king

- 1 2 Schmidl, Petra G. (1996–97). "Two Early Arabic Sources On The Magnetic Compass". Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies. 1: 81–132. http://www.uib.no/jais/v001ht/01-081-132schmidl1.htm#_ftn4

- ↑ Moussa, Ali (2011). "Mathematical Methods in Abū al-Wafāʾ's Almagest and the Qibla Determinations". Arabic Sciences and Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. 21 (1). doi:10.1017/S095742391000007X.

- ↑ Savage-Smith, Emilie (1988). "Gleanings from an Arabist's Workshop: Current Trends in the Study of Medieval Islamic Science and Medicine". Isis. 79 (2): 246–266 [263]. doi:10.1086/354701.

- ↑ Schmidl, Petra G. (2007). "Ashraf: al‐Malik al‐Ashraf (Mumahhid al‐Dīn) ʿUmar ibn Yūsuf ibn ʿUmar ibn ʿAlī ibn Rasūl". In Thomas Hockey et al. The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780387310220. (PDF version)

- ↑ "The Correct Qiblah - missing" Archived January 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. S. Kamal Abdali

- ↑ "Malaysian Conf. Probes How Muslim Astronauts Pray" Archived 2006-05-25 at the Wayback Machine. on Islam Online

- ↑ "First Muslim to Fast Ramadan in Space" Archived 2007-11-17 at the Wayback Machine. on Islam Online

- ↑ "Question & Answer - Qibla"

- ↑ Di Justo, Patrick (26 September 2007). "A Muslim Astronaut's Dilemma: How to Face Mecca From Space". Wired. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

Further reading

- King, David (2005). "The Sacred Geography of Islam". In Koetsier, Teun; Bergmans, Luc. Mathematics and the Divine: A Historical Study (1st ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. pp. 161–178. ISBN 0-444-50328-5.

- King, David A. (1999). World maps for finding the direction and distance to Mecca : innovation and tradition in Islamic science. Islamic philosophy, theology, and science. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-11367-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qibla. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Kiblah. |

- Full information of the Kaaba

- The City of Jerusalem in Islam (Al-Quds) About.com

- Second Year of the Hijra at al-islam.org (Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project)

- Qiblah In North America – argues that the Qiblah is based on a rhumb line path

- Determining the Sacred Direction of Islam

- Denis Roegel: An Extension of Al-Khalīlī's Qibla Table to the Entire World, 2008

Online tools

- Qiblah.us

- Accurate Qibla calculator Gives highly accurate Qibla and distance to Mecca using the WGS84 ellipsoid

- Qibla Direction

- eQibla.com – worldwide Qibla Direction (including documents and Qibla formula)

- Qiblah Direction Finder

- QiblaDirection.com uses Google Maps and Google Earth to draw a line between your location and Mecca, automatically gives the prayer times for your location

- Find Qibla using rhumb line and great circle, also compute magnetic declination

- Qibla finder Widget for Konfabulator

- Type your address to see a map showing your Qibla Direction

- Qibla Finder

-Jerusalem-Temple_Mount-Dome_of_the_Rock_(SE_exposure).jpg)