Maronites

| |

| Religions | |

|---|---|

| Christianity (Syriac Maronite Church) | |

| Languages | |

|

Liturgical: Syriac[1] Vernacular: Arabic (in Israel and Lebanon);[2][1] Neo-Aramaic (small minority in Galilee region of Israel, with language revival efforts underway);[2][3] Greek (in Cyprus); Cypriot Maronite Arabic (historically in Cyprus)[4] |

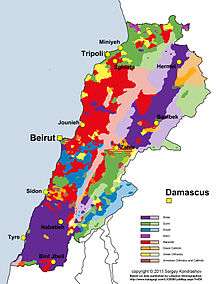

The Maronites are a Christian group[5] who adhere to the Syriac Maronite Church with the largest population around Mount Lebanon in Lebanon. The Maronite Church is an Eastern Catholic sui iuris particular church in full communion with the Pope and the Catholic Church,[6] with self-governance under the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, one of more than a dozen individual churches in full communion with the Holy See. They derive their name from the Syriac Christian saint Maron, whose followers migrated to the area of Mount Lebanon from their previous location of residence around the area of Antioch, establishing the nucleus of the Syriac Maronite Church.[7] Some Maronites argue that they are of Mardaite ancestry, but most historians reject such claims.[8] Maronites were able to maintain an independent status in Mount Lebanon and its coastline after the Muslim conquest of the Levant, keeping their Christian religion, and even the distinctive Aramaic language as late as the 19th century.[7]

The Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate of the Ottoman Empire and later the republic of Lebanon were created under the auspice of European powers with the Maronites as their main ethnoreligious component. Mass emigration to the Americas at the outset of the 20th century, famine mainly resulting from Turkish blockades and confiscations during World War I that killed an estimated third to half of the population, the Lebanese Civil War between 1975-1990 and the low fertility rate greatly decreased their numbers in the Levant. Maronites today form more than one quarter of the total population in the Republic of Lebanon. With only two exceptions, all Lebanese presidents have been Maronites as part of a tradition that persists as part of the National Pact, by which the Prime Minister has historically been a Sunni Muslim and the Speaker of the National Assembly has historically been a Shi'i Muslim.

Though concentrated in Lebanon, Maronites also show presence in neighboring Syria, Israel, Cyprus and Palestine, as well as a significant part in the Lebanese diaspora in the Americans, Europe, Australia, and Africa.

The Syriac Maronite Church, under the Patriarch of Antioch, has branches in nearly all countries where Maronite Christian communities live, in both the Levant (mainly Lebanon) and the Lebanese diaspora.

Name

The reason for the adoption of the name Maronite is disputed and historians disagree whether it refers to Mar Maron, a 3rd-century Syriac Christian saint, or to John Maron, the first Maronite Patriarch (ruled 685-707).[9][10]

History

The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Lebanese people is a blend of both indigenous Phoenician elements and the foreign cultures that have come to rule the land and its people over the course of thousands of years. In a 2013 interview, Pierre Zalloua, a Lebanese biologist who took part in the National Geographic Society's Genographic Project, pointed out that genetic variation preceded religious variation and divisions:"Lebanon already had well-differentiated communities with their own genetic peculiarities, but not significant differences, and religions came as layers of paint on top. There is no distinct pattern that shows that one community carries significantly more Phoenician than another."[11]

A number of Maronite historians assert that their people, along with their non-Christian countrymen, are also the descendants of the Arameans, Ghassanids, Assyrians, and the Mardaites, residents in parts of Caliphate province of Bilad al-Sham, who kept their identity under both Byzantine and Arab authorities.

The Mardaites were mountaineers from the Taurus that Constantinople recruited to infiltrate Lebanon and join the Maronites in harassing the Arabs. The resistance movement became known as Marada, meaning rebels. In 936, the monastery of Bet Moroon and other Maronite monasteries were completely destroyed in Syria and the Aramaic/ Syriac Maronites took refugee and joined the Phoenician Maronites and the Mardaites in the mountains of Lebanon.[12]

In the 6th century most Maronites were killed by Jacobite Christian Syriacs.[9] Following the Muslim conquest of the Levant, the patriarch of the Maronites fled to the Byzantine Empire, with his replacement being chosen by the remaining Maronite faithful.[9] Under Byzantine, or Muslim pressure, the Maronites migrated from the Orontes River valley, in northern Syria,[13] to Mount Lebanon in the late 9th century, where they became "civilly semiautonomous"[9][14][15] and were known to speak Arabic in daily life and use Syriac for their liturgy - a scenario that was originally replicated among Christian Arabs even in pre-Islamic times.[16] The Maronites are believed to have settled in the mountains of Lebanon since it provided a refuge for the group, which were viewed as Christian 'dissenters' by the Byzantine church.[17] Historically, this has also been the case for Shi'ites, Druze (who joined the Maronites in the mountains in the 9th and 11th centuries, respectively) and Alawites, seeking havens from Sunni pressure, which dominated the coast.[17][18] Following the Byzantine conquests of the Orontes valley, by the late 11th century the Maronites were driven out of the valley region and confined to the Lebanon Mountains and a small community in Muslim-controlled Aleppo.[19]

The Maronites welcomed the conquering Christians of the First Crusade.[17] Around the late 12th century, according to William of Tyre, the Maronites numbered 40,000 people.[20] During the papacy of Pope Gregory XIII (1572-1585), steps were taken to bring the Maronites still closer to Rome.[21] By the 17th century, the Maronites had developed a strong natural liking to Europe - particularly France.[22] The Maronites have also had a presence in Cyprus since the early 9th century and many Maronites went there following Saladin's successful Siege of Jerusalem.[18]

In the 19th century, thousands of Maronites were massacred by Druze during the 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war.

Population

Lebanon

According to the Maronite church, there are approximately 1,062,000 Maronites in Lebanon, where they constitute up to 22% of the population.[23] Under the terms of an informal agreement, known as the National Pact, between the various political and religious leaders of Lebanon, the president of the country must be a Maronite Christian.[24]

Syria

There is also a small Maronite Christian community in Syria. In 2017, the Annuario Pontificio reported that 3,300 people belonged to the Archeparchy of Aleppo, 15,000 in the Archeparchy of Damascus and 45,000 in the Eparchy of Lattaquié).[25] In 2015, the BBC placed the number of Maronites in Syria at between 28,000 and 60,000.[26]

Cyprus

Maronites first migrated to Cyprus in the 8th century, and there are approximately 5,800 Maronites on the island today, the vast majority in the Greek portion.[4] The community historically spoke Cypriot Maronite Arabic,[27][28] but today Cypriot Maronites speak the Greek language, with the Cypriot government designating Cypriot Maronite Arabic as a dialect.[4]

Israel

A Maronite community of about 11,000 people lives in Israel.[29] The 2017 Annuario Pontificio reported that 10,000 people belonged to the Maronite Catholic Archeparchy of Haifa and the Holy Land and 504 people belonged to the Exarchate of Jerusalem and Palestine.[25]

In 2014, Israel decided to recognize the Aramean community within its borders as a national minority, allowing some Christians in Israel to be registered as "Aramean" instead of Arab.[30] The Christians, who may apply for recognition as Aramean, are mostly Galilean Maronites, who trace their culture, ancestry and language to Aramean-speaking pre-Arab population of the Levant. In addition, some 500 Christian adherents of the Syriac Catholic Church in Israel are expected to apply for the recreated ethnic status, as well as several hundred Aramaic-speaking adherents of the Syriac Orthodox Church.[31] Though supported by Gabriel Naddaf, the move was condemned by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, which described it as "an attempt to divide the Palestinian minority in Israel".[32]

Diaspora

| Part of a series on |

| Maronite Church |

|---|

|

| Patriarch |

| Religious orders and societies |

| Communities |

| Languages |

|

|

| History |

| Related politics |

|

|

According to the Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, "accurate figures are not available, but it is probable that the Maronite diaspora of over 3 million individuals is about three times larger" than the Maronite population living in their historic homelands in Lebanon, Syria, and Israel.[33]

According to the Annuario Pontificio, in 2017 the Eparchy of San Charbel in Buenos Aires, Argentina has 750,000 members; the Eparchy of Our Lady of Lebanon of São Paulo, Brazil had 501,000 members; the Eparchy of Saint Maron of Sydney, Australia had 152,300 members; the Eparchy of Saint Maron of Montreal, Canada had 89,775 members; the Eparchy of Our Lady of the Martyrs of Lebanon in Mexico had 159,403 members; the Eparchy of Our Lady of Lebanon of Los Angeles in the United States had 46,000 members; and the Eparchy of Saint Maron of Brooklyn in the United States had 33,000 members.[25]

According to the Annuario Pontificio, 50,944 people belonged to the Maronite Catholic Eparchy of Our Lady of Lebanon of Paris in 2017.[25] In Europe, some Belgian Maronites are involved in the trade of diamonds in the diamond district of Antwerp.[34]

According to the Annuario Pontificio, 66,495 belonged to the Apostolic Exarchate of West and Central Africa (Nigeria) in 2017.[25]

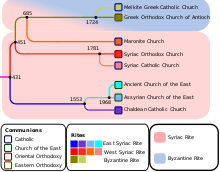

Identity

The followers of the Maronite Church form a part of the Syriac Christians and belong to the West Syriac Rite. The Maronite Syriac Church of Antioch traces its foundation to Maron, an early 3rd-century Syriac monk venerated as a saint.[35][36] Before the conquest by Arabian Muslims reached Lebanon, the Lebanese people, including those who would become Muslim and the majority who would remain Christian, spoke a dialect of Aramaic called Syriac.[37][38][39] Syriac remains the liturgical language of the Maronite Church.[40]

Phoenicianism

Phoenicianism is an identity on the part of Lebanese Christians that has developed into an integrated ideology led by key thinkers, but there are a few who have stood out more than others: Charles Corm, Michel Chiha, and Said Aql in their promotion of Phoenicianism.[41] In post civil-war Lebanon since the Taif agreement, politically Phoenicianism is restricted to a small group.[41]

Among leaders of the movement Etienne Saqr, Said Akl, Charles Malik, Camille Chamoun, and Bachir Gemayel have been notable names, some going as far as voicing anti-Arab views. In his book the Israeli writer Mordechai Nisan, who at times met with some of them during the war, quoted Said Akl, a famous Lebanese poet and philosopher, as saying;

| “ | "I would cut off my right hand, and not associate myself to an Arab."[42] | ” |

Akl believes in emphasizing the Phoenician legacy of the Lebanese people and has promoted the use of the Lebanese dialect written in a modified Latin alphabet, rather than the Arabic one, although both alphabets have descended from the Phoenician alphabet.[43]

In opposition to such views, Arabism was affirmed at the March 1936 Congress of the Coast and Four Districts, when the Muslim leadership at the conference made the declaration that Lebanon was an Arab country, indistinguishable from its Arab neighbors. In the April 1936 Beirut municipal elections, Christian and Muslim politicians were divided along Phoenician and Arab lines in the matter of whether the Lebanese coast should be claimed by Syria or given to Lebanon, increasing the already mounting tensions between the two communities.[41] Phoenicianism is still disputed by many Arabist scholars who have on occasion tried to convince its adherents to abandon their claims as false, and to embrace and accept the Arab identity instead.[43] This conflict of ideas of identity is believed to be one of the pivotal disputes between the Muslim and Christian populations of Lebanon and what mainly divides the country to the detriment of national unity.[44]

In general it appears that Muslims focus more on the Arab identity of the Lebanese history and culture whereas the older, long-standing Christian communities, especially the Maronites focus on their history, and struggles as an ethnoreligious group in an Arab world, while also reaffirming the Lebanese identity, and refraining from Arab characterization as it would deny them their striving achievement of having fended off the Arabs and Turks physically, culturally, and spiritually since their conception. The Maronite perseverance lead to their existence even today.[45] [46]

Support for Lebanese identity

Lebanese Maronites are known to be specifically linked to the root of Lebanese Nationalism and opposition to Pan-Arabism in Lebanon, this being the case during 1958 Lebanon crisis. When Muslim Arab nationalists backed by Gamel Abdel Nasser tried to overthrow the then Maronite dominated government in power, due to displeasure at the government's pro-western policies and their lack of commitment and duty to the so-called "Arab brotherhood" by preferring keep Lebanon away from the Arab League and the political confrontations of the Middle East. A more hard-nosed nationalism among some Maronites leaders, who saw Lebanese nationalism more in terms of its confessional roots and failed to be carried away by Chiha's vision, clung to a more security-minded view of Lebanon. They regarded the national project as mainly a program for the security of Maronites and a bulwark against threats from Muslims and their hinterland.[47]

The right-wing yet secular Guardians of the Cedars, with its exiled Leader and founder Etienne Saqr (also the father of singers Karol Sakr and Pascale Sakr) took no sectarian stance and even had Muslim members who joined in their radical stance against Arabism and Palestinian forces in Lebanon.[48] Saqr summarized his party's view on the Arab Identity on their official ideological manifesto by stating;

| “ | Lebanon will remain, as always, Lebanese without any labels. The French passed through it yet it remained Lebanese. The Ottomans ruled it and it remained Lebanese. The stinky winds of Arabism blows through it, but the wind will wither away and Lebanon will remain Lebanese. I do not know what will become of those wretched people who claim that Lebanon is Arabic when Arabism disappears from the map of the Middle East and a new Middle East would emerge, which is clean from Arabs and Arabism.[49] | ” |

On an Al Jazeera special dedicated to the political Christian clans of Lebanon and their struggle for power in the 2009 election entitled, Lebanon: The Family Business the issue of identity was brought up on several occasions, by various politicians including Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, who claimed that all Lebanese lack somewhat of a real identity and the country is yet to discover one everybody could agree on. Sami Gemayel, of the Gemayel clan and son of former president Amin Gemayel, stated he did not consider himself an Arab but instead identified himself as a Syriac Christian, going on to explain that to him and many Lebanese the "acceptance" of Lebanon's "Arab identity" according to the Taef Agreement wasn't something that they "accepted" but instead were forced into signing through pressure.

| “ | The official declared "Arab Identity" of Lebanon was created in 1990 based on the Taif Agreement, without any free discussion or debate among Lebanese people and while Lebanon was under Syrian custody and in the presence of armed Syrian military inside the Lebanese parliament when votes on constitutional amendments were taking place.[50] | ” |

In a speech in 2009 to a crowd of Christian Kataeb supporters Gemayel declared that he felt there was importance in Christians in Lebanon finding an identity and went on to state what he finds identification with as a Lebanese Christian, concluding with a purposeful exclusion of Arabism in the segment. The speech met with an applause afterward from the audience;[50]

| “ | What we are missing today is an important element of our life and our honor, which is our identity. I will tell you today, that I as a Lebanese citizen, my identity is Maronite, Syriac Christian, and Lebanese (Arabic: مارونية سريانية مسيحية لبنانية Maroniya, Syryaniya Masïhiya, Lubnaniya).[50] | ” |

Etienne Sakr, of the Guardians of the Cedars Lebanese party, in an interview responded "We are not Arabs" to an interview question about the Guardians of the Cedars' ideology of Lebanon being Lebanese. He continued by talking about how describing Lebanon as being not Arab was a crime in present-day Lebanon, about the Lebanese Civil War, and about Arabism as being first step towards Islamism, claiming that "the Arabs want to annex Lebanon" and in order to do this "to push the Christians out (out of Lebanon)", this being "the plan since 1975", among other issues.[51]

Embrace of Arab identity

During a final session of the Lebanese Parliament, a Marada Maronite MP states his identity as an Arab: "I, the Maronite Christian Lebanese Arab, grandson of Patriarch Estefan Doueihy, declare my pride to be a part of our people’s resistance in the South. Can one renounce what guarantees his rights?"[52]

Maronite Deacon Soubhi Makhoul, administrator for the Maronite Exarchate in Jerusalem, has said "The Maronites are Arabs, we are part of the Arab world. And although it’s important to revive our language and maintain our heritage, the church is very outspoken against the campaign of these people.” [53]

Aramean identity in Israel

The Maronite Christian residents of Jish have recently begun to mainly refer to themselves as Aramean Christian Maronite peoples and not as Arabs or Lebanese Arabs.[54] This status was officially approved in 2014 by the Israeli government and any Maronite Christian can register as ethnically Aramean instead of Arab or unassigned ethnic group.

Culture

Religion

The Maronites belong to the Maronite Syriac Church of Antioch (a former ancient Greek city now in Hatay Province, Turkey) is an Eastern Catholic Syriac Church, using the Antiochian Rite, that had affirmed its communion with Rome since 1180 A.D., although the official view of the Church is that it had never accepted either the Monophysitic views held by their Syriac neighbours, which were condemned in the Council of Chalcedon, or the failed compromise doctrine of Monothelitism (the latter claim being found in contemporary sources, with evidence that they were Monothelites for several centuries, beginning in the early 7th century).[55] name=Moosa>Moosa, M (2005). The Maronites in History. Gorgias Press LLC. pp. 209–210. ISBN 978-1-59333-182-5. </ref> The Maronite Patriarch is traditionally seated in Bkerke north of Beirut.

Names

Modern Maronites often adopt French or other Western European given names (with biblical origins) for their children, including Michel, Marc, Marie, Georges, Carole, Charles, Antoine, Joseph, Pierre, Christian, Christelle and Rodrigue.

Given names of Arabic origins identical with those of their Muslim neighbors are also common, such as Khalil, Toufic, Jamil, Samir, Salim or Hisham. Other common names are strictly Christian and are Aramaic, or Arabic, forms of biblical, Hebrew, or Greek Christian names, such as Antun (Anthony or Antonios), Butros (Peter), Boulos (Paul), Semaan or Shamaoun (Simon or Simeon), Jergyes (George), Elie (Ilyas or Elias), Iskander (Alexander) and Beshara (literally Good News in reference to the Gospel). Other common names are Sarkis (Sergius) and Bakhos (Bacchus), while others are common both among Christians and Muslims, such as Youssef (Joseph) or Ibrahim (Abraham).

Some Maronite Christians are named in honour of Maronite saints, including the Aramaic names Maro(u)n (after their patron saint Maron), Nimtullah, Charbel of Sharbel after Saint Charbel Makhluf and Rafqa (Rebecca).

Persecution and struggle

Maronites were persecuted during the Byzantine empire, followed by the Arab invasion of the Middle East (Mount Lebanon) and finally by the Ottoman Empire. The Great Famine of Mount Lebanon, which occurred between 1915 and 1918, was caused by the Ottoman policy of acquiring all food products produced in the region for the Ottoman army and administration, and the barring of any produce from being sent to the Maronite Christian population of Mount Lebanon, effectively condemning them to starvation.[56] It was suggested at the time that the starvation of the Maronites was a deliberately orchestrated Ottoman policy aimed at destroying the Maronites, in keeping with the treatment of Armenians, Assyrians and Greeks.[57] The death toll among Maronite Christians, mainly due to starvation and disease is estimated to have been 200,000.[58]

Maronite Christians felt a sense of alienation and exclusion as a result of Pan-Arabism in Lebanon.[59][60] Part of its historic suffering is the Damour massacre by the PLO. Until recently, the Cyprus Maronites battled to preserve their ancestral language.[61] The Maronite monks maintain that Lebanon is synonymous with Maronite history and ethos; that its Maronitism antedates the Arab conquest of Lebanon and that Arabism is only a historical accident.[62] The Maronites also felt mass persecution under the Ottoman Turks, who massacred and mistreated Maronites for their faith, disallowing them from owning horses and forcing them to wear only black clothing. The Turkish Ottoman Empire slew upwards of 300,000 Maronites, forced the remaining populations into the mountains (which spawned Mount Lebanon) and let another 100,000 die of starvation while stranded with no means of self-sufficiency. The Lebanese Druze also persecuted the Maronites, and massacred in excess of 50,000 of them in the mid-1800s. However, agreements have been held with the druze. Moreover, the Maronites later emerged as the most dominant group in Lebanon a status they held until the sectarian conflict that resulted in the Lebanese Civil War.

See also

References

- 1 2 Lebanon - Maronites, World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples Minority Rights Group International: "Originally Aramaic speakers, today Maronites speak Arabic, but use Syriac as a liturgical language."

- 1 2 Judith Sudilovsky, Aramaic classes help Maronites in Israel understand their liturgies, Catholic News Service (June 22, 2012).

- ↑ Daniella Cheslow, Maronite Christians struggle to define their identity in Israel, The World, Public Radio International (June 30, 2014).

- 1 2 3 Educational Policies that Address Social Inequality: Country Report: Cyprus, page 4.

- ↑ Salibi, Kamal S. (1988). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. I.B.Tauris. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-86064-912-7.

- ↑ Moubarak, Andre (2017). One Friday in Jerusalem. Jerusalem, Israel: Twin Tours & Travel Ltd. p. 213. ISBN 9780999249420.

- 1 2 Mannheim, I (2001). Syria & Lebanon handbook: the travel guide. Footprint Travel Guides. pp. 652–563. ISBN 978-1-900949-90-3.

- ↑ Moosa, Matti (2005). The Maronites in history. Gorgias Press LLC. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-59333-182-5. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 P. J. A. N. Rietbergen (2006). Power And Religion in Baroque Rome: Barberini Cultural Policies. BRILL. p. 299. ISBN 9789004148932.

- ↑ Moosa, Matti (2005). The Maronites in History. Gorgias Press LLC. pp. 14–14. ISBN 978-1-59333-182-5.

- ↑ Maroon, Habib (31 March 2013). "A geneticist with a unifying message". Nature. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ↑ "History of the Maronites".

- ↑ Jack Donnelly; Rhoda E. Howard-Hassmann (1 Jan 1987). International Handbook of Human Rights. ABC-CLIO. p. 228. ISBN 9780313247880.

- ↑ Rome and the Eastern Churches (revised ed.). Ignatius Press. 2010. p. 327. ISBN 9781586172824.

- ↑ Michael Haag (9 Jul 2010). Templars: History and Myth: From Solomon's Temple to the Freemasons. Profile Books. p. 66. ISBN 9781847652515.

- ↑ Kamal S. Salibi (2003). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). I.B.Tauris. p. 90. ISBN 9781860649127.

- 1 2 3 James Minahan (1 Jan 2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: L-R (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1196. ISBN 9780313321115.

- 1 2 Ernest Gellner (1 Jan 1985). Islamic Dilemmas: Reformers, Nationalists, Industrialization : The Southern Shore of the Mediterranean. Walter de Gruyter. p. 258. ISBN 9783110097634.

- ↑ Kamal S. Salibi (2003). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). I.B.Tauris. pp. 90–1. ISBN 9781860649127.

- ↑ Kenneth M. Setton; Norman P. Zacour; Harry W. Hazard (1 Sep 1985). A History of the Crusades: The Impact of the Crusades on the Near East (illustrated ed.). Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 91. ISBN 9780299091446.

- ↑ P. J. A. N. Rietbergen (2006). Power And Religion in Baroque Rome: Barberini Cultural Policies. BRILL. p. 301. ISBN 9789004148932.

- ↑ James Minahan (1 Jan 2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: L-R (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 1196–7. ISBN 9780313321115.

- ↑ Lebanon - International Religious Freedom Report 2008 U.S. Department of State. Retrieved on 2009-09-04.

- ↑ United Nations Development Programme : Programme on Governance in the Arab Region : Elections : Lebanon Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Maronite Catholic Church (Patriarchate)" in "The Eastern Catholic Churches 2017" in Annuario Pontificio 2017.

- ↑ Syria's beleaguered Christians, BBC News (February 25, 2015).

- ↑ Maria Tsiapera, A Descriptive Analysis of Cypriot Maronite Arabic, 1969, Mouton and Company, The Hague, 69 pages

- ↑ Cyprus Ministry of Interior : European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages : Answers to the Comments/Questions Submitted to the Government of Cyprus Regarding its Initial Periodical Report Archived 2010-11-26 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ↑ Ami Bentov (2014-05-26). "Cardinal is first top Lebanese cleric in Israel". Associated Press. Retrieved 2014-05-26.

- ↑ "Ministry of Interior to Admit Arameans to National Population Registry - Latest News Briefs - Arutz Sheva". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ "אנחנו לא ערבים - אנחנו ארמים" (in Hebrew). Israel HaYom. 9 August 2013.

- ↑ Cohen, Ariel (28 September 2014). "Israeli Greek Orthodox Church denounces Aramaic Christian nationality". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ "Maronites" in Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East (Infobase, 2009), p. 446.

- ↑ Ian Traynor, Recession takes the sparkle out of Antwerp's diamond quarter. The Guardian (June 23, 2009).

- ↑ ". Identity of the Maronite Church - Introduction". Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ ". Identity of the Maronite Church - A Syriac Antiochene Church with a Special Lit. Heritage". Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ "Review of Phares Book". Walidphares.com. Archived from the original on 2009-02-10. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

- ↑ The Precarious Republic: Political Modernization in Lebanon. By Michael C. Hudson, 1968

- ↑ Lebanon: Its Stand in History Among the Near East Countries By Salim Wakim, 1996.

- ↑ "St. George Maronite Church". Stgeorgesa.org. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

- 1 2 3 Reviving Phoenicia: in search of ... - Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ "The Conscience of Lebanon". Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- 1 2 "The Middle East". Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ "The Identity of Lebanon". Mountlebanon.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ↑ "Coalition of American Assyrians and Maronites Rebukes Arab American Institute". Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ "Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Catholic Church". Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ "Notes on the Question of Lebanese Nationalism". Lcps-lebanon.org. Archived from the original on 2007-10-07. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ↑ The conscience of Lebanon: a ... - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ↑ "The Guardians of the Cedars". Gotc.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- 1 2 3 "Lebanon: The family business – 31 May 09 – Part 4". YouTube. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ↑ "Interview with Etienne Saqr (Abu Arz)". Global Politician. 2008-01-22. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ↑ "The vote of confidence debate – final session | Ya Libnan | World News Live from Lebanon". LB: Ya Libnan. 2009-12-11. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ↑

- ↑ "Aramaic Maronite Center". Aramaic-center.com. Retrieved 2012-11-26.

- ↑ name="Greenwood Publishing Group"

- ↑ BBC staff (26 November 2014). "Six unexpected WW1 battlegrounds". BBC News (BBC). BBC News Services. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ↑ Ghazal, Rym (14 April 2015). "Lebanon's dark days of hunger: The Great Famine of 1915–18". The National. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ↑ Harris 2012, p.174

- ↑ The war for Lebanon, 1970-1985 - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ↑ Conversion and continuity ... - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ↑ Martelli, Simon (2010-03-03). "AFP: Cyprus Maronites battle to preserve ancestral language". Google.com. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ↑ The Maronites in History – Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maronites. |