Beta Israel

Beta Israel memorial in Mount Herzl | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 150,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

1.75% of the Israeli population, >2.15% of Israeli Jews | |

| 4,000[2] | |

| 1,000[3] | |

| Languages | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Judaism (Haymanot · Rabbinism) · Christianity (Ethiopian Orthodox – see Falash Mura and Beta Abraham) | |

Beta Israel (Hebrew: בֵּיתֶא יִשְׂרָאֵל, Beyte (beyt) Yisrael; Ge'ez: ቤተ እስራኤል, Bēta 'Isrā'ēl, modern Bēte 'Isrā'ēl, EAE: "Betä Ǝsraʾel", "House of Israel" or "Community of Israel"[4]), also known as Ethiopian Jews (Hebrew: יְהוּדֵי אֶתְיוֹפְּיָה: Yehudey Etyopyah; Ge'ez: የኢትዮጵያ አይሁድዊ, ye-Ityoppya Ayhudi), are Jews whose community developed and lived for centuries in the area of the Kingdom of Aksum and the Ethiopian Empire that is currently divided between the Amhara and Tigray Regions of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Most of these peoples have emigrated to Israel since the late 20th century.[5]

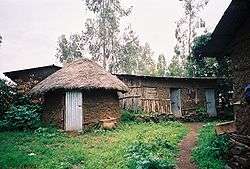

The Beta Israel lived in northern and northwestern Ethiopia, in more than 500 small villages spread over a wide territory, alongside populations that were Muslim and predominantly Christian.[6] Most of them were concentrated in the area around and to the north of Lake Tana, in the Gondar region among the Wolqayit, Shire and Tselemt, Dembia, Segelt, Quara, and Belesa.

The Beta Israel made renewed contacts with other Jewish communities in the later 20th century. After Halakhic and constitutional discussions, Israeli officials decided on March 14, 1977, that the Israeli Law of Return applied to the Beta Israel.[7] The Israeli and American governments mounted aliyah operations[8] to transport the people to Israel.[9] These activities included Operation Brothers in Sudan between 1979 and 1990 (this includes the major operations Moses and Joshua), and in the 1990s from Addis Ababa (which includes Operation Solomon).[10][11]

By the end of 2008, there were 119,300 people of Ethiopian descent in Israel, including nearly 81,000 people born in Ethiopia and about 38,500 native-born Israelis (about 32 percent of the community) with at least one parent born in Ethiopia or Eritrea.[12]

Terminology

_Takuyo.jpg)

Throughout its history, the community has been referred to by numerous names. According to tradition the name "Beta Israel" (literally "house of Israel" in Ge'ez) originated in the 4th century CE, when the community refused to convert to Christianity during the rule of Abreha and Atsbeha (identified with Se'azana and Ezana), the monarchs of the Kingdom of Aksum who embraced Christianity.[13]

This name contrasts with "Beta Kristiyan" (literally "house of Christianity", referring to "church" in Ge'ez).[14][15] Originally it did not have any negative connotations,[16] and the community has since used Beta Israel as its official name. Since the 1980s, it has also become the official name used in the scholarly and scientific literature to refer to the community.[17] The term Esra'elawi "Israelites" – which is related to the name Beta Israel – is also used by the community to refer to its members.[17]

The name Ayhud "Jews" is rarely used in the community, as the Christians had used it as a derogatory term.[16] The community has begun to use it only since strengthening ties with other Jewish communities in the 20th century.[17] The term Ibrawi "Hebrew" was used to refer to the Chawa (free man) in the community, in contrast to Barya "slave".[18] The term Oritawi "Torah-true" was used to refer to the community members; since the 19th century it has been used in opposition to the term Falash Mura (converts).

The derogatory term Falasha, meaning "landless, wanderers," was given to the community by the Emperor Yeshaq I in the 15th century, and is to be avoided as extremely offensive. Zagwe, referring to the Agaw people of the Zagwe dynasty, among the original inhabitants of northwest Ethiopia, is considered derogatory since it incorrectly associates the community with the largely pagan Agaw.[17]

Religion

Haymanot (Ge'ez: ሃይማኖት) is the colloquial term for "faith" used in the Jewish religion in the community;[19] although it is also used by Ethiopian Orthodox Christians for their religion.

Texts

Mäṣḥafä Kedus (Holy Scriptures) is the name for their religious literature. The language of the writings is Ge'ez, which also is the liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Some say that this language is the parent language of modern Amharic and Tigrinya, but this is not quite accurate: it is more closely related to Tigrinya.[20] The holiest book is the Orit (meaning "law") which consists of the Octateuch: Five Books of Moses with Joshua, Judges and Ruth. The rest of the Bible has secondary importance. Sources are lacking on whether the Book of Lamentations is excluded from the canon, or whether it forms part of the Book of Jeremiah as it does in the Orthodox Tewahedo biblical canon.

Deuterocanonical books that also make up part of the canon are Sirach, Judith, Esdras 1 and 2, Meqabyan, Jubilees, Baruch 1 and 4, Tobit, Enoch, and the testaments of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Important non-Biblical writings include: Nagara Muse (The Conversation of Moses), Mota Aaron (Death of Aharon), Mota Muse (Death of Moses), Te'ezaza Sanbat (Precepts of Sabbath), Arde'et (Students), Gorgorios, Mäṣḥafä Sa'atat (Book of Hours), Abba Elias (Father Elija), Mäṣḥafä Mäla'əkt (Book of Angels), Mäṣḥafä Kahan (Book of Priest), Dərsanä Abrəham Wäsara Bägabs (Homily on Abraham and Sarah in Egypt), Gadla Sosna (The Acts of Susanna) and Baqadāmi Gabra Egzi'abḥēr (In the Beginning God Created). Zëna Ayhud (Jews Story) and Fālasfā (Philosophers) are two books that are not considered sacred but have had great influence.

Prayer house

The synagogue is called masgid (place of worship), also bet maqdas (Holy house) or ṣalot bet (Prayer house).

Dietary laws

Beta Israel kashrut law is based mainly on the books of Leviticus, Deuteronomy and Jubilees. Permitted and forbidden animals and their signs appear on Leviticus 11:3–8 and Deuteronomy 14:4–8. Forbidden birds are listed on Leviticus 11:13–23 and Deuteronomy 14:12–20. Signs of permitted fish are written on Leviticus 11:9–12 and Deuteronomy 14:9–10. Insects and larvae are forbidden according to Leviticus 11:41–42. Waterfowl are forbidden according to Leviticus 11:46. Gid hanasheh is forbidden per Genesis 32:33. Mixtures of milk and meat are not prepared or eaten but are not banned either: Haymanot interpreted the verses Exodus 23:19, Exodus 34:26 and Deuteronomy 14:21 "shalt not seethe a kid in its mother's milk" literally, as in Karaite Judaism. Nowadays, under the influence of Rabbinic Judaism, mixing dairy products with meat is banned.

Ethiopian Jews were forbidden to eat the food of non-Jews. A Kahen eats only meat he has slaughtered himself, which his hosts prepare both for him and themselves. Beta Israel who broke these taboos were ostracized and had to undergo a purification process. Purification included fasting for one or more days, eating only uncooked chickpeas provided by the Kahen, and ritual purification before entering the village.

Unlike other Ethiopians, the Beta Israel do not eat raw meat dishes such as kitfo or gored gored.[21]

Calendar and holidays

The Beta Israel calendar is a lunar calendar of 12 months, each 29 or 30 days alternately. Every four years there is a leap year which added a full month (30 days). The calendar is a combination of the ancient calendar of Alexandrian Jewry, Book of Jubilees, Book of Enoch, Abu Shaker, and the Ge'ez calendar.[22][23] The years are counted according to the counting of Kushta: "1571 to Jesus Christ, 7071 to the Gyptians and 6642 to the Hebrews";[24] according to this counting, the year 5771 (Hebrew: ה'תשע"א) in the Rabbinical Hebrew calendar is the year 7082 in this calendar.

Holidays in the Haymanot (religion)[25] are divided into daily, monthly and annually. The annual holidays by month are:

- Nisan: ba'āl lisan (Nisan holiday – New Year) on 1, ṣomä fāsikā (Passover fast) on 14, fāsikā (Passover) between 15–21 and gadfat (grow fat) or buho (fermented dough) on 22.

- Iyar: another fāsikā (Second Passover – Pesach Sheni) between 15–21.

- Sivan: ṣomä mã'rar (Harvest fast) on 11 and mã'rar (Harvest – Shavuot) on 12.

- Tammuz: ṣomä tomos (Tammuz fast) between 1–10.

- Av: ṣomä ab (Av fast) between 1–17.

- Elul: awd amet (Year rotate) on 1, ṣomä lul (Elul fast) between 1–9, anākel astar'i (our atonement) on 10 and asartu wasamantu (eighteenth) on 28.

- Tishrei: ba'āl Matqe (blowing holiday – Zikhron Trua) on 1, astasreyo (Day of Atonement – Yom Kippur) on 10 and ba'āla maṣallat (Tabernacles holiday – Sukkot) between 15–21.

- Cheshvan: holiday for the day Moses saw the face of God on 1, holiday for the reception of Moses by the Israelites on 10, fast on 12 and měhlělla (Supplication – Sigd) on 29.

- Kislev: another ṣomä mã'rar and mã'rar on 11 and 12 respectively.

- Tevet: ṣomä tibt (Tevet fast) between 1–10.

- Shevat: wamashi brobu on 1.

- Adar: ṣomä astēr (Fast of Esther – Ta'anit Ester) between 11–13.

Monthly holidays are mainly memorial days to the annual holiday, these are yačaraqā ba'āl ("new moon festival")[26] on the first day of every month, asärt ("ten") on the tenth day to commemorate Yom Kippur, 'asrã hulat ("twelve") on the twelfth day to commemorate Shavuot, asrã ammest ("fifteen") on the fifteenth day to commemorate Passover and Sukkot, and ṣomä mälěya a fast on the last day of every month.[27] Daily holidays include the ṣomä säňňo (Monday fast), ṣomä amus (Thursday fast), ṣomä 'arb (Friday fast) and the very holy Sanbat (Sabbath).

Culture

Languages

The Beta Israel once spoke Qwara and Kayla, Agaw languages. Now they speak Amharic and Tigrinya, both Semitic languages. Their liturgical language is Ge'ez, also Semitic.[28][29] Since the 1950s, they have taught Hebrew in their schools. Those Beta Israel residing in the State of Israel now use Modern Hebrew as a daily language.

Origins

Oral traditions

Many of the Beta Israel accounts of their own origins stress that they stem from the very ancient migration of some portion of the Tribe of Dan to Ethiopia, led it is said by sons of Moses, perhaps even at the time of the Exodus, or perhaps due to later crises in Judea, e.g., at the time of the split of the northern Kingdom of Israel from the southern Kingdom of Judah after the death of King Solomon or at the time of the Babylonian Exile.[30] Other Beta Israel take as their basis the Christian account of Menelik's return to Ethiopia.[31] Menelik is considered the first Solomonic Emperor of Ethiopia, and is traditionally believed to be the son of King Solomon of ancient Israel, and Makeda, ancient Queen of Sheba (in modern Ethiopia). Though all the available traditions[32] correspond to recent interpretations, they reflect ancient convictions. According to Jon Abbink; three different versions are to be distinguished among the traditions which were recorded from the priests of the community.[33]

Companions of Menelik from Jerusalem

By versions of this type, the Beta Israel expressed their belief that they were not necessarily descendants of King Solomon, but contemporaries of Solomon and Menelik, originating from the kingdom of Israel.[34]

Migrants by the Egyptian route

According to these versions, the forefathers of the Beta Israel are supposed to have arrived in Ethiopia coming from the North, independently from Menelik and his company:

The Falashas [sic] migrated like many of the other sons of Israel to exile in Egypt after the destruction of the First Temple by the Babylonians in 586 BCE the time of the Babylonian exile. This group of people was led by the great priest On. They remained in exile in Egypt for few hundred years until the reign of Cleopatra. When she was engaged in war against Augustus Caesar the Jews supported her. When she was defeated, it became dangerous for the small minorities to remain in Egypt and so there was another migration (approximately between 39–31 BCE). Some of the migrants went to South Arabia and further to the Yemen. Some of them went to the Sudan and continued on their way to Ethiopia, helped by Egyptian traders who guided them through the desert. Some of them entered Ethiopia through Quara (near the Sudanese border), and some came via Eritrea.

...Later in time, there was an Abyssinian king named Kaleb, who wished to enlarge his kingdom, so he declared war on the Yemen and conquered it. And so, during his reign there arrived another group of Jews to Ethiopia, led by Azonos and Phinhas.[35]:413–414

Kebra Nagast

The Ethiopian history described in the Kebra Nagast relates that Ethiopians are descendants of Israelite tribes who came to Ethiopia with Menelik I, alleged to be the son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (or Makeda, in the legend) (see 1 Kings 10:1–13 and 2 Chronicles 9:1–12). The legend relates that Menelik, as an adult, returned to his father in Jerusalem, and later resettled in Ethiopia. He took with him the Ark of the Covenant.[36][37]

In the Bible there is no mention that the Queen of Sheba either married or had any sexual relations with King Solomon (although some identify her with the "black and beautiful" in Song of Songs 1:5).[38] Rather, the narrative records that she was impressed with Solomon's wealth and wisdom, and they exchanged royal gifts, and then she returned to rule her people in Kush. However, the "royal gifts" are interpreted by some as sexual contact. The loss of the Ark is not mentioned in the Bible. Hezekiah later makes reference to the Ark in 2 Kings 19:15.

The Kebra Negast asserts that the Beta Israel are descended from a battalion of men of Judah who fled southward down the Arabian coastal lands from Judea after the breakup of the Kingdom of Israel into two kingdoms in the 10th century BCE (while King Rehoboam reigned over Judah).

Although the Kebra Nagast and some traditional Ethiopian histories have stated that Gudit (or "Yudit", Judith; another name given her was "Esato", Esther), a 10th-century usurping queen, was Jewish, some scholars consider that it is unlikely that this was the case. It is more likely, they say, that she was a pagan southerner[39] or a usurping Christian Aksumite Queen.[40] However, she clearly supported Jews, since she founded the Zagwe dynasty, who governed from around 937 to 1270 CE. According to the Kebra Nagast, Jewish, Christian and pagan kings ruled in harmony at that time. Furthermore, the Zagwe dynasty claimed legitimacy (according to the Kebra Nagast) by saying it was descended from Moses and his Ethiopian wife.

Most of the Beta Israel consider the Kebra Negast to be legend. As its name expresses, "Glory of Kings" (meaning the Christian Aksumite kings), it was written in the 14th century in large part to delegitimize the Zagwe dynasty, to promote instead a rival "Solomonic" claim to authentic Jewish Ethiopian antecedents, and to justify the Christian overthrow of the Zagwe by the "Solomonic" Aksumite dynasty, whose rulers are glorified. The writing of this polemic shows that criticisms of the Aksumite claims of authenticity were current in the 14th century, two centuries after they came to power. Many Beta Israel believe that they are descended from the tribe of Dan.[41] Most reject the "Solomonic" and "Queen of Sheba" legends of the Aksumites.

Tribe of Dan

To prove the antiquity and authenticity of their claims, the Beta Israel cite the 9th-century CE testimony of Eldad ha-Dani (the Danite), from a time before the Zagwean dynasty was established. Eldad was a Jewish man of dark skin who appeared in Egypt and created a stir in that Jewish community (and elsewhere in the Mediterranean Jewish communities he visited) with claims that he had come from a Jewish kingdom of pastoralists far to the south. The only language Eldad spoke was a hitherto unknown dialect of Hebrew. Although he strictly followed the Mosaic commandments, his observance differed in some details from Rabbinic halakhah. Some observers thought that he might be a Karaite, although his practice also differed from theirs. He carried Hebrew books that supported his explanations of halakhah. He cited ancient authorities in the scholarly traditions of his own people.[42]

Eldad said that the Jews of his own kingdom descended from the tribe of Dan (which included the Biblical war-hero Samson) who had fled the civil war in the Kingdom of Israel between Solomon's son Rehoboam and Jeroboam the son of Nebat, and resettled in Egypt. From there they moved southwards up the Nile into Ethiopia. The Beta Israel say this confirms that they are descended from these Danites.[43] Some Beta Israel, however, assert that their Danite origins go back to the time of Moses, when some Danites parted from other Jews right after the Exodus and moved south to Ethiopia. Eldad the Danite speaks of at least three waves of Jewish immigration into his region, creating other Jewish tribes and kingdoms. The earliest wave settled in a remote kingdom of the "tribe of Moses": this was the strongest and most secure Jewish kingdom of all, with farming villages, cities and great wealth.[44] Other Ethiopian Jews who appeared in the Mediterranean world over the succeeding centuries and persuaded rabbinic authorities there that they were of Jewish descent, and so could if slaves be ransomed by Jewish communities, join synagogues, marry other Jews, etc, also referred to the Mosaic and Danite origins of Ethiopian Jewry.[45] The Mosaic claims of the Beta Israel, in any case, like those of the Zagwe dynasty, are ancient.[46]

Other sources tell of many Jews who were brought as prisoners of war from ancient Israel by Ptolemy I and settled on the border of his kingdom with Nubia (Sudan). Another tradition asserts that the Jews arrived either via the old district of Qwara in northwestern Ethiopia, or via the Atbara River, where the Nile tributaries flow into Sudan. Some accounts specify the route taken by their forefathers on their way upriver to the south from Egypt.[47]

Rabbinical views

As mentioned above, the 9th-century Jewish traveler Eldad ha-Dani claimed the Beta Israel descended from the tribe of Dan. He also reported other Jewish kingdoms around his own or in East Africa during this time. His writings probably represent the first mention of the Beta Israel in Rabbinic literature. Despite some skeptical critics, his authenticity has been generally accepted in current scholarship. His descriptions were consistent and even the originally doubtful rabbis of his time were finally persuaded.[48] Specific details may be uncertain; one critic has noted Eldad's lack of detailed reference to Ethiopia's geography and any Ethiopian language, although he claimed the area as his homeland.[49]

Eldad's was not the only medieval testimony about Jewish communities living far to the south of Egypt, which strengthens the credibility of his account. Obadiah ben Abraham Bartenura wrote in a letter from Jerusalem in 1488:

I myself saw two of them in Egypt. They are dark-skinned...and one could not tell whether they keep the teaching of the Karaites, or of the Rabbis, for some of their practices resemble the Karaite teaching...but in other things they appear to follow the instruction of the Rabbis; and they say they are related to the tribe of Dan.[50]

Reflecting the consistent assertions made by Ethiopian Jews they dealt with or knew of, after due investigation of their claims and their own Jewish behaviour, a number of Jewish legal authorities not only in modern times but also in previous centuries have ruled halakhically that the Beta Israel are indeed Jews, the descendants of the tribe of Dan, one of the Ten Lost Tribes.[51] They believe that these people established a Jewish kingdom that lasted for hundreds of years. With the rise of Christianity and later Islam, schisms arose and three kingdoms competed. Eventually, the Christian and Muslim Ethiopian kingdoms reduced the Jewish kingdom to a small impoverished section. The earliest authority to rule this way was David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra (1479–1573), who explains in a responsum concerning the status of a Beta Israel slave:

But those Jews who come from the land of Cush are without doubt from the tribe of Dan, and since they did not have in their midst sages who were masters of the tradition, they clung to the simple meaning of the Scriptures. If they had been taught, however, they would not be irreverent towards the words of our sages, so their status is comparable to a Jewish infant taken captive by non-Jews… And even if you say that the matter is in doubt, it is a commandment to redeem them.[52]

In 1973 Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, then the Chief Sephardic Rabbi, based on the Radbaz and other accounts, ruled that the Beta Israel were Jews and should be brought to Israel. He was later joined by a number of other authorities who made similar rulings, including the Chief Ashkenazi Rabbi Shlomo Goren.[53]

Some notable poskim, from non-Zionist Ashkenazi circles, placed a safek "legal doubt" over the Jewish peoplehood of the Beta Israel. Such dissenting voices include rabbis Elazar Shach, Yosef Shalom Eliashiv, Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, and Moshe Feinstein.[54][55] Similar doubts were raised within the same circles towards the Bene Israel[56] and to Russian immigrants to Israel during the 1990s Post-Soviet aliyah.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, the Beta Israel were required to undergo a modified conversion ceremony involving immersion in a mikveh, a declaration accepting Rabbinic law, and, for men, a "symbolic recircumcision".[57] Chief Rabbi Avraham Shapira later waived the "symbolic recircumcision" demand, which is only required when the halakhic doubt is significant.[58] More recently, Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar has ruled that descendants of Ethiopian Jews who were forced to convert to Christianity are "unquestionably Jews in every respect".[59] With the consent of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, Rabbi Amar ruled that it is forbidden to question the Jewishness of this community, pejoratively called Falash Mura in reference to their having converted.[60][61]

Genetics

According to Cruciani et al. (2002), haplogroup A is the most common paternal lineage among Ethiopian Jews. The clade is carried by around 41% of Beta Israel males, and is primarily associated with Nilo-Saharan and Khoisan-speaking populations. Additionally, around 18% of Ethiopian Jews are bearers of E-P2 (xM35, xM2), in Ethiopia most of such lineages belong to E-M329, which has been found in ancient DNA isolated from a 4,500 year old Ethiopian fossil.[62][63][64] Such haplotypes are frequent in Southwestern Ethiopia, especially among Omotic-speaking populations.[65][66] The rest of the Beta Israel mainly belong to haplotypes linked with the E1b1b and J haplogroups, which are instead associated with local Afroasiatic-speaking populations in Northeast Africa. Altogether, this suggests that Ethiopian Jews have diverse patrilineages indicative of both Afroasiatic and non-Afroasiatic origins for this community.[67]

A 2001 study by the Department of Biological Sciences at Stanford University found a possible genetic similarity between 11 Ethiopian Jews and four Yemenite Jews who took part in the testing. The differentiation statistic and genetic distances for the 11 Ethiopian Jews and four Yemenite Jews tested were quite low, among the smallest of comparisons involving either of these populations. The four Yemenite Jews from this study may be descendants of reverse migrants of Ethiopian origin who crossed Ethiopia to Yemen. The study result suggests gene flow between Ethiopia and Yemen as a possible explanation for the closeness. The study also suggests that the gene flow between Ethiopian and Yemenite Jewish populations may not have been direct, but instead could have been between Jewish and non-Jewish populations of both regions.[68]

The Ethiopian Jews' autosomal DNA has been examined in a comprehensive study by Tishkoff et al. (2009) on the genetic affiliations of various populations in Africa. According to Bayesian clustering analysis, the Beta Israel generally grouped with other Afroasiatic-speaking populations inhabiting the Horn of Africa, North Africa and the Sahara.[69]

A 2010 study by Behar et al. on the genome-wide structure of Jews observed that the Beta Israel had levels of the Middle Eastern genetic clusters similar to the Semitic-speaking Tigrayans and Amharas.[70]

Kidd et al. (2011) examined ancestry informative markers among other Ethiopian Jews and found that their population sample was heterogeneous in composition. The genetic markers of each analysed individual were assigned to eight different population clusters according to probability of best fit. Some of the Beta Israel individuals' markers were predominantly assigned to various non-African clusters (primarily to the Middle Eastern cluster, as with the other Jewish populations), whereas other Beta Israel individuals' markers were predominantly assigned to various African clusters (primarily to the cluster associated with Nilo-Saharan speakers). The other Horn of Africa individuals also had heterogeneous ancestry informative marker affinities, but more often possessed comparatively higher probabilities of assignment to the South/Central Asia cluster and lower probabilities of assignment to the Middle Eastern and Nilo-Saharan clusters than the Ethiopian Jew individuals.[71]

A number of other DNA studies have been done on the Beta Israel.[72]

Scholarly views

Early views

Early secular scholars considered the Beta Israel to be the direct descendant of Jews who lived in ancient Ethiopia, whether they were the descendants of an Israelite tribe, or converted by Jews living in Yemen, or by the Jewish community in southern Egypt at Elephantine.[73] In 1829, Marcus Louis wrote that the ancestors of the Beta Israel related to the Asmach, which were also called Sembritae ("foreigners"), an Egyptian regiment numbering 240,000 soldiers and mentioned by Greek geographers and historians. The Asmach emigrated or were exiled from Elephantine to Kush in the time of Psamtik I or Psamtik II and settled in Sennar and Abyssinia.[74] It is possible that Shebna's party from Rabbinic accounts was part of the Asmach.

In the 1930s Jones and Monro argued that the chief Semitic languages of Ethiopia may suggest an antiquity of Judaism in Ethiopia. "There still remains the curious circumstance that a number of Abyssinian words connected with religion, such as the words for Hell, idol, Easter, purification, and alms– are of Hebrew origin. These words must have been derived directly from a Jewish source, for the Abyssinian Church knows the scriptures only in a Ge'ez version made from the Septuagint."[75]

Richard Pankhurst summarized the various theories offered about their origins as of 1950 that the first members of this community were

(1) converted Agaws, (2) Jewish immigrants who intermarried with Agaws, (3) immigrant Yemeni Arabs who had converted to Judaism, (4) immigrant Yemeni Jews, (5) Jews from Egypt, and (6) successive waves of Yemeni Jews. Traditional Ethiopian savants, on the one hand, have declared that 'We were Jews before we were Christians', while more recent, well-documented, Ethiopian hypotheses, notably by two Ethiopian scholars, Dr Taddesse Tamrat and Dr Getachew Haile...put much greater emphasis on the manner in which Christians over the years converted to the Falasha faith, thus showing that the Falashas were culturally an Ethiopian sect, made up of ethnic Ethiopians.[76]

1980s and early 1990s

According to Jacqueline Pirenne, numerous Sabaeans left south Arabia and crossed over the Red Sea to Ethiopia to escape from the Assyrians, who had devastated the kingdoms of Israel and Judah in the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. She says that a second major wave of Sabeans crossed over to Ethiopia in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE to escape Nebuchadnezzar II. This wave also included Jews fleeing from the Babylonian takeover of Judah. In both cases the Sabeans are assumed to have departed later from Ethiopia to Yemen.[77]

According to Menachem Waldman, a major wave of emigration from the Kingdom of Judah to Kush and Abyssinia dates to the Assyrian Siege of Jerusalem, in the beginning of the 7th century BCE. Rabbinic accounts of the siege assert that only about 110,000 Judeans remained in Jerusalem under King Hezekiah's command, whereas about 130,000 Judeans led by Shebna had joined Sennacherib's campaign against Tirhakah, king of Kush. Sennacherib's campaign failed and Shebna's army was lost "at the mountains of darkness", suggestively identified with the Semien Mountains.[78]

In 1987 Steve Kaplan wrote:

Although we don't have a single fine ethnographic research on Beta Israel, and the recent history of this tribe has received almost no attention by researchers, every one who writes about the Jews of Ethiopia feels obliged to contribute his share to the ongoing debate about their origin. Politicians and journalists, Rabbis and political activists, not a single one of them withstood the temptation to play the role of the historian and invent a solution for this riddle.[79]

Richard Pankhurst summarized the state of knowledge on the subject in 1992 as follows: "The early origins of the Falashas are shrouded in mystery, and, for lack of documentation, will probably remain so for ever."[76]

Recent views

By 1994 modern scholars of Ethiopian history and Ethiopian Jews generally supported one of two conflicting hypotheses for the origin of the Beta Israel, as outlined by Kaplan:[80]

- An ancient Jewish origin, together with conservation of some ancient Jewish traditions by the Ethiopian Church. Kaplan identifies Simon D. Messing, David Shlush, Michael Corinaldi, Menachem Waldman, Menachem Elon and David Kessler as supporters of this hypothesis.[80]

- A late ethnogenesis of the Beta Israel between the 14th to 16th centuries, from a sect of Ethiopian Christians who took on Biblical Old Testament practices, and came to identify as Jews. Steven Kaplan supports this hypothesis, and lists with him G. J. Abbink, Kay K. Shelemay, Taddesse Tamrat and James A. Quirin. Quirin differs from his fellow researchers in the weight he assigns to an ancient Jewish element which the Beta Israel have conserved.[80]

History

Ancient history

Political independence (4th century – 1632)

According to the Beta Israel tradition, the Jewish kingdom of Beta Israel, later called the kingdom of Gondar, was initially established after Ezana was crowned as the Emperor of Axum (in 325 CE). Ezana, who was educated in his childhood by the missionary Frumentius, declared Christianity as the religion of the Ethiopian empire after he was crowned. The inhabitants who practiced Judaism and refused to convert to Christianity began revolting – this group was referred to as "Beta Israel" by the emperor. Following civil war between the Jewish population and the Christian population the Beta Israel appear to have forged an independent state, either in northern western Ethiopia or the eastern region of Northern Sudan. By the 13th century, the Beta Israel have already moved to the more easily defensible mountains to the northwest of the Christianized region of the plains.[81] The kingdom was located in the Semien Mountains region and the Dembia region – situated to the north of Lake Tana and south of the Tekezé River. They made their main city at Gondar, crowned their first king, Phineas, a descendent of the Jewish High Priest Zadok, and started a period of territorial expansion eastward and southward.

During the mid-9th century, the empire of Aksum began a new expansion, which led to an armed conflict between the Empire forces and the Beta Israel forces. The Beta Israel kingdom under King Gideon the fourth managed to defeat the Axum forces. During the battle king Gideon was killed. As a result, Gideon's daughter Judith inherited the kingdom from her father and took command.

Queen Judith signed a pact with the Agaw tribes which were pagans. Around 960, The large tribal confederation led by Queen Judith, which included both forces of the Agaw tribes and the Beta Israel forces, invaded the capital of Axum and conquered and destroyed the city of Axum (including many churches and monasteries which were burned and destroyed) and imposed the Jewish rule over Axum. In addition, the Axumite throne was snatched and the forces of Queen Judith sacked and burned the Debre Damo monastery which at the time was a treasury and a prison for the male relatives of the emperor of Ethiopia, killing all of the potential heirs of the emperor.

The Golden Age of the Beta Israel kingdom took place, according to the Ethiopian tradition, between the years 858–1270, in which the Jewish kingdom flourished. During that period the world Jewry heard for the first time the stories of Eldad ha-Dani who either visited the kingdom or heard many accounts of it in his own Jewish kingdom of pastoralists, which may have been located in the Sudan (since he speaks of the Mosaic kingdom lying on "the other side of the rivers of Ethiopia" in remote mountains). Even Marco Polo and Benjamin of Tudela mention an independent Ethiopian Jewish kingdom in the writings from that period. This period ends with the rise of the Christian Solomonic dynasty – In 1270 the Christian Solomonic dynasty was "restored" after the crowning of a monarch who claimed descent from the single royal prince who managed to escape Queen Judith's uprising. For the next three centuries, the Solomonic dynasty emperors conducted several long ongoing series of armed confrontations with the Jewish kingdom.

In 1329, Emperor Amda Seyon campaigned in the northwest provinces of Semien, Wegera, Tselemt, and Tsegede, in which many had been converting to Judaism and where the Beta Israel had been gaining prominence.[82] He sent troops there to fight people "like Jews" (Ge'ez ከመ:አይሁድ kama ayhūd).[83]

During the reign of Emperor Yeshaq (1414–1429) who invaded the Jewish kingdom, annexed it and began to exert religious pressure. Yeshaq divided the occupied territories of the Jewish kingdom into three provinces which were controlled by commissioners appointed by him. He reduced the Jews' social status below that of Christians[83] and forced the Jews to convert or lose their land. It would be given away as rist, a type of land qualification that rendered it forever inheritable by the recipient and not transferable by the Emperor. Yeshaq decreed, "He who is baptized in the Christian religion may inherit the land of his father, otherwise let him be a Falāsī." This may have been the origin for the term "Falasha" (falāšā, "wanderer," or "landless person").[83] This term is considered derogatory to Ethiopian Jews.

In 1435, Elijah of Ferrara recounted meeting an Ethiopian Jew in Jerusalem in a letter to his children. The man told him of the ongoing conflict of his independent nation with the Christian Habesha; he relayed some of the principals of his faith, which, Ferrara concluded, balanced between Karaite and Rabbinical Judaism. His people were not familiar with the Talmud and did not observe Hanukkah, but their canon contained the book of Esther and they had an oral interpretation of the Torah. Ferrara further recorded that they had their own language, that the journey from their land lasted six months, and that the biblical Gozan river was found within their borders.[84]

By 1450 the Jewish kingdom managed to annex back the territories it lost beforehand and began preparing to fight the armies of the emperor. The Beta Israel forces invaded the Ethiopian Empire in 1462 but lost the campaign and many of its military forces were killed. Later on the forces of the Ethiopian emperor invaded the kingdom in the region of Begemder and massacred many of the Jews in that region throughout a period of seven years. The Emperor Yacob Zara (reigned 1434–1468) even proudly added the title "Exterminator of the Jews" to his name. Although the area of the kingdom became significantly smaller afterwards, the Jews were able to eventually restore their mountain kingdom.

Between the years 1529 until 1543 the Muslim Adal Sultanate armies with the assistance of forces from the Ottoman Empire invaded and fought the Ethiopian Empire and came close to extinguishing the ancient realm of Ethiopia, and converting all of its subjects to Islam. During that time period the Jews made a pact with the Ethiopian Empire. The leaders of the Kingdom of Beta Israel changed their alliance during the war and began supporting the Muslim Adal Sultanate armies. However, the Adal Sultanate armies felt strong enough to ignore this offer of support and killed many of its members. As a result, the leaders of the Beta Israel kingdom turned to the Ethiopian empire and their allies, and continued the fight against them. They conquered different regions of the Jewish kingdom, severely damaged its economy and requested their assistance in winning back the regions lost to the Adal Sultanate. The forces of the Ethiopian empire did succeed eventually in conquering the Muslims and freed Ethiopia from Ahmed Gragn. Nevertheless, the Ethiopian Christian empire decided to declare war against the Jewish Kingdom, giving as their justification the Jewish leaders' change of positions during the Ethiopian–Adal War. With the assistance of Portuguese forces from the Order of the Jesuits, the Ethiopian empire under the rule of Emperor Gelawdewos invaded the Jewish kingdom and executed the Jewish king Joram. As a result of this battle, the areas of the kingdom became significantly smaller and included now only the region of the Semien Mountains.

In the 16th century, the Chief Rabbi of Egypt, Rabbi David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra (Radbaz) proclaimed that in terms of halakha (Jewish legal code), the Ethiopian community was certainly Jewish.[85]

After the execution of King Joram, King Radi became the leader of the Beta Israel kingdom. King Radi also fought against the Ethiopian Empire which at that period of time was ruled by Emperor Menas. The forces of the Jewish kingdom managed to conquer the area south of the kingdom and strengthened their defenses in the Semien Mountains. The battles against the forces of emperor Menas were successful as the Ethiopian empire forces were eventually defeated.

During the reign of emperor Sarsa Dengel the Jewish kingdom was invaded and the forces of the Ethiopian empire besieged the kingdom. The Jews survived the siege, but at the end of the siege the King Goshen was executed and many of his soldiers as well as many other Beta Israel members committed mass suicides.[86]

During the reign of Susenyos I the Ethiopian empire waged war against the Jewish kingdom and managed to conquer the entire kingdom and annex it to the Ethiopian empire by 1627.

Gondar period (1632–1855)

After the Beta Israel autonomy in Ethiopia ended in the 1620s, Emperor Susenyos I confiscated their lands, sold many people into slavery and forcibly baptized others.[87] In addition, Jewish writings and religious books were burned and the practice of any form of Jewish religion was forbidden in Ethiopia. As a result of this period of oppression, much traditional Jewish culture and practice was lost or changed.

Nonetheless, the Beta Israel community appears to have continued to flourish during this period. The capital of Ethiopia, Gondar, in Dembiya, was surrounded by Beta Israel lands. The Beta Israel served as craftsmen, masons, and carpenters for the Emperors from the 16th century onwards. Such roles had been shunned by Ethiopians as lowly and less honorable than farming.[87] According to contemporary accounts by European visitors: Portuguese merchants and diplomats, French, British and other travellers, the Beta Israel numbered about one million persons in the 17th century. These accounts also recounted that some knowledge of Hebrew persisted among the people in the 17th century. For example, Manoel de Almeida, a Portuguese diplomat and traveller of the day, wrote that:

There were Jews in Ethiopia from the first. Some of them were converted to the law of Christ Our Lord; others persisted in their blindness and formerly possessed many wide territories, almost the whole Kingdom of Dambea and the provinces of Ogara and Seman. This was when the [Christian] empire was much larger, but since the [pagan and Muslim] Gallas have been pressing in upon them [from the east and south], the Emperors have pressed in upon them [i.e., the Jews to the west?] much more and took Dambea and Ogara from them by force of arms many years ago. In Seman, however, they defended themselves with great determination, helped by the position and the ruggedness of their mountains. Many rebels ran away and joined them till the present Emperor Setan Sequed [throne name of Susneyos], who in his 9th year fought and conquered the King Gideon and in his 19th year attacked Samen and killed Gideon. ... The majority and the flower of them were killed in various attacks and the remainder surrendered or dispersed in different directions. Many of them received holy baptism but nearly all were still as much Jews as they had been before. There are many of the latter in Dambea and in various regions; they live by weaving cloth and by making zargunchos [spears], ploughs and other iron articles, for they are great smiths. Between the Emperor’s kingdoms and the Cafres [Negroes] who live next to the Nile outside imperial territory, mingled together with each other are many more of these Jews who are called Falashas here. The Falashas or Jews are ... of [Arabic] race [and speak] Hebrew, though it is very corrupt. They have their Hebrew Bibles and sing the psalms in their synagogues.[88]

The sources of De Almeida's knowledge are not spelled out, but they at least reflect contemporary views. His comments regarding the Hebrew knowledge of the Beta Israel of that time is very significant: it could not have come from recent intercourse with Jews elsewhere, so it indicates deep antiquity to Beta Israel traditions, at least at that time, before their literature was taken away from them and demolished by the later conquering Christians. (The more sceptical school of historians, whose views are discussed above, deny that the Ethiopian Jews ever knew Hebrew; they certainly have no Hebrew texts remaining, and have been forced in recent centuries to use the Christian "Old Testament" in Ge'ez after their own literature was destroyed.) It is also of interest that he mentions more Jewish communities dwelling beyond Ethiopia in the Sudan. As so often in such medieval hearsay accounts, however, loose claims are made that may not be accurate. The Beta Israel were not predominantly of the Arabic race, for instance, but he may have meant the term loosely or meant that they also knew Arabic.

The isolation of the Beta Israel community in Ethiopia, and their continuing use of some Hebrew, was also reported by the Scottish explorer James Bruce who published his travelogue Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile in Edinburgh in 1790.

The Beta Israel lost their relative economic advantage in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, during the Zemene Mesafint, a period of recurring civil strife. Although the capital was nominally in Gondar during this time period, the decentralization of government and dominance by regional capitals resulted in a decline and exploitation of Beta Israel by local rulers. No longer was there a strong central government interested in and capable of protecting them.[87] During this period, the Jewish religion was effectively lost for some forty years, before being restored in the 1840s by Abba Widdaye, the preeminent monk of Qwara.[87]

Modern history

The contemporary history of the Beta Israel community begins with the reunification of Ethiopia in the mid-19th century during the reign of Tewodros II. At that time, the Beta Israel population was estimated at between 200,000 to 350,000 people.[89]

Christian missions and the Rabbinical reformation

Despite occasional contacts in an earlier stage, the West only became well-aware of the existence of the Beta Israel community when they came in contact through the Protestant missionaries of the "London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews" which specialized in the conversion of Jews.[90] The organization began its operating in Ethiopia in 1859. The Protestant missionaries, who worked under the direction of a converted Jew named Henry Aaron Stern, converted many of the Beta Israel community to Christianity. Between 1859 and 1922, about 2,000 Beta Israel members converted to Orthodox Christianity (they did not convert to Protestantism due to an agreement the Protestant missionaries had with the government of Ethiopia). The relatively low amount of conversions is partly explained by the strong reaction to the conversions from religious leadership of the Beta Israel community. The Beta Israel members who were converted to Christianity are known today as "Falash Mura".

The Protestant missionaries' activities in Ethiopia provoked European Jewry. As a result, several European rabbis proclaimed that they recognized the Jewishness of the Beta Israel community, and eventually in 1868 the organization "Alliance Israélite Universelle" decided to send the Jewish-French Orientalist Joseph Halévy to Ethiopia in order to study the conditions of the Ethiopian Jews. Upon his return to Europe, Halévy made a very favorable report of the Beta Israel community in which he called for world Jewish community to save the Ethiopian Jews, to establish Jewish schools in Ethiopia, and even suggested to bring thousands of Beta Israel members to settle in Ottoman Syria (a dozen years before the actual establishment of the first Zionist organization).

Nevertheless, after a brief period in which the media coverage generated a great interest in the Beta Israel community, the interest among the Jewish communities world wide declined. This happened mainly because serious doubts still remained about the Jewishness of the Beta Israel community and because the Alliance Israélite Universelle organization did not comply with Halévy's recommendations.

Between 1888 and 1892, northern Ethiopia experienced a devastating famine. The famine was caused by rinderpest that killed the majority of all cattle (see 1890s African rinderpest epizootic). Conditions worsened with cholera outbreaks (1889–92), a typhus epidemic, and a major smallpox epidemic (1889–90).

About one-third of the Ethiopian population died during that period.[91][92] It is estimated that between a half to two-thirds of the Beta Israel community died during that period.

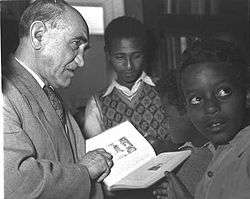

The myth of the lost tribes in Ethiopia intrigued Jacques Faitlovitch, a former student of Joseph Halévy at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes in Paris. In 1904 Faitlovitch decided to lead a new mission in northern Ethiopia. Faitlovitch obtained funding from the Jewish philanthropist Edmond de Rothschild, traveled and lived among the Ethiopian Jews. In addition, Faitlovitch managed to disrupt the efforts of the Protestant missionaries to convert the Ethiopian Jews, who at the time attempted to persuade the Ethiopian Jews that all the Jews in the world believe in Jesus. Between the years 1905–1935, he brought out 25 young Ethiopian Jewish boys, whom he planted in the Jewish communities of Europe,[93] for example Salomon Yeshaq,[94] Taamerat Ammanuel,[95] Abraham Adgeh,[96] Yona Bogale,[97] and Tadesse Yacob.[98]

Following his visit in Ethiopia, Faitlovitch created an international committee for the Beta Israel community, popularized the awareness of their existence through his book Notes de voyage chez les Falashas, and raised funds to enable the establishment of schools in their villages.[29]

In 1908, the chief rabbis of 45 countries made a joint statement officially declaring that Ethiopian Jews were indeed Jewish.

The Jewishness of the Beta Israel community became openly supported amongst the majority of the European Jewish communities during the early 20th century.

In 1921 Abraham Isaac Kook, the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of the British Mandate for Palestine, recognized the Beta Israel community as Jews.

The Italian period, World War II and the post war period

In 1935 armed forces of the Kingdom of Italy headed by the fascist leader Benito Mussolini invaded and occupied Ethiopia. Ethiopia officially surrendered in 1936.

The Italian regime showed hostility towards the Jews of Ethiopia. The racial laws which were enacted in Italy were also applied to Italian East Africa. Mussolini attempted to reach an agreement with Britain which would recognize Italian East Africa, during which Mussolini proposed to solve the "Jewish problem" in Europe and in Palestine by resettling the Jews in the north-west Ethiopian districts of Gojjam and Begemder along with the Beta Israel community.[99][100] The proposed Jewish state was to be federally united with the Italian Empire. Mussolini's plan was never implemented.

When the State of Israel was established in 1948 many Ethiopian Jews began contemplating immigrating to Israel. Nevertheless, the Emperor Haile Selassie refused to grant the Ethiopian Jewish population permission to leave his empire.

Early illegal emigration and the official Israeli recognition

Between the years 1965 and 1975 a relatively small group of Ethiopian Jews immigrated to Israel. The Beta Israel immigrants in that period were mainly a very few men who had studied and come to Israel on a tourist visa and then remained in the country illegally.

Some supporters in Israel who recognized their Jewishness decided to assist them. These supporters began organizing associations, including one under the direction of Ovadia Hazzi, a Yemeni Jew and former sergeant in the Israeli army who married a wife from the Beta Israel community after the Second World War.[101] Some of the illegal immigrants managed to regularize their status with the Israeli authorities through the assistance of these support associations. Some agreed to "convert" to Judaism, which helped them to regularize their personal status and thus remain in Israel. Those who had regularized their status often brought their families to Israel as well.

In 1973, Ovadia Hazzi officially raised the question of the Jewishness of the Beta Israel to the Israeli Sephardi Rabbi Ovadia Yosef. The rabbi, who cited a rabbinic ruling from the 16th century David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra and asserted that the Beta Israel are descended from the lost tribe of Dan, acknowledged their Jewishness in February 1973. This ruling was initially rejected by the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi Shlomo Goren, who eventually changed his opinion on the matter in 1974.

In April 1975, the Israeli government of Yitzhak Rabin officially accepted the Beta Israel as Jews, for the purpose of the Law of Return (an Israeli act that grants all the Jews in the world the right to immigrate to Israel).

Later on, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin obtained clear rulings from Chief Sephardi Rabbi Ovadia Yosef that they were descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes. The Chief Rabbinate of Israel did however initially require them to undergo pro forma Jewish conversions, to remove any doubt as to their Jewish status.

Ethiopian Civil War

After a period of civil unrest on September 12, 1974, a pro-communist military junta, known as the "Derg" ("committee") seized power after ousting the emperor Haile Selassie I. The Derg installed a government which was socialist in name and military in style. Lieutenant Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam assumed power as head of state and Derg chairman. Mengistu's years in office were marked by a totalitarian-style government and the country's massive militarization, financed by the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, and assisted by Cuba. Communism was officially adopted by the new regime during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

As a result, the new regime gradually began to embrace anti-religious and anti-Israeli positions as well as showing hostility towards the Jews of Ethiopia.

Towards the mid-1980s Ethiopia underwent a series of famines, exacerbated by adverse geopolitics and civil wars, which eventually resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands.[102] As a result, the lives of hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians, including the Beta Israel community, became untenable and a large part tried to escape the war and the famine by fleeing to neighboring Sudan.

Concern for the fate of the Ethiopian Jews and fear for their well-being contributed eventually to the Israeli government's official recognition of the Beta Israel community as Jews in 1975, for the purpose of the Law of Return. Civil war in Ethiopia prompted the Israeli government to airlift most of the Beta Israel population in Ethiopia to Israel in several covert military rescue operations which took place from the 1980s until the early 1990s.

Emigration to Israel

| Years | Ethiopian-born Immigrants | Total Immigration to Israel |

|---|---|---|

| 1948–51 | 10 | 687,624 |

| 1952–60 | 59 | 297,138 |

| 1961–71 | 98 | 427,828 |

| 1972–79 | 306 | 267,580 |

| 1980–89 | 16,965 | 153,833 |

| 1990–99 | 39,651 | 956,319 |

| 2000–04 | 14,859 | 181,505 |

| 2005-09 | 12,586 | 86,855 |

| 2010 | 1,652 | 16,633 |

| 2011 | 2,666 | 16,892 |

| 2012 | 2,432 | 16,557 |

| 2013 | 450 | 16,968 |

Beta Israel Exodus

| Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries |

|---|

|

| Communities |

| Background |

| Main events |

| Resettlement |

| Advocation |

| Related topics |

The emigration to Israel of the Beta Israel community was officially banned by the Communist Derg government of Ethiopia during the 1980s, although it is now known that General Menghistu collaborated with Israel to receive money and arms in exchange for allowing the Beta Israel safe passage during Operation Moses.[105][106] Other Beta Israel who did not participate in either Operations or Solomon sought alternative ways of immigration, via Sudan or Kenya.

- Late 1979 – beginning of 1984 – aliyah activists and Mossad agents operating in Sudan called the Jews to come to Sudan, and told them that, from Sudan via Europe they would be taken to Israel. Posing as Christian Ethiopian refugees from the Ethiopian Civil War, Jews began to arrive in the refugee camps in Sudan. Most Jews came from Tigray and Wolqayt, regions that were controlled by the TPLF, who often escorted them to the Sudanese border.[107] Small groups of Jews were brought out of Sudan in a clandestine operation that continued until an Israeli newspaper exposed the operation and brought it to a halt stranding Beta Israels in the Sudanese camps. In 1981, the Jewish Defense League protested the "lack of action" to rescue Ethiopian Jews by taking over the main offices of HIAS in Manhattan.[108]

- 1983 – March 28, 1985 – In 1983 the governor of Gondar region, Major Melaku Teferra was ousted, and his successor removed restrictions on travel out of Ethiopia.[109] Ethiopian Jews, many by this time waiting in Addis Ababa, began again to arrive in Sudan in large numbers; and the Mossad had trouble evacuating them quickly. Because of the poor conditions in the Sudanese camps, many Ethiopian refugees, both Christian and Jewish, died of disease and hunger. Among these victims, it is estimated that between 2,000 to 5,000 were Jews.[110] In late 1984, the Sudanese government, following the intervention of the U.S, allowed the emigration of 7,200 Beta Israel refugees to Europe who then went on to Israel. The first of these two immigration waves, between 20 November 1984 and 20 January 1985, was dubbed Operation Moses (original name "The Lion of Judah’s Cub") and brought 6,500 Beta Israel to Israel. This operation was followed by Operation Joshua (also referred to as "Operation Sheba") a few weeks later, which was conducted by the U.S. Air Force, and brought the 494 Jewish refugees remaining in Sudan to Israel. The second operation was mainly carried out due to the critical intervention and pressure from the U.S.

Emigration via Addis Ababa

- 1990–1991 – After losing Soviet military support following the collapse of Communism in Central and Eastern Europe, the Ethiopian government allowed the emigration of 6,000 Beta Israel members to Israel in small groups, mostly in hope of establishing ties with the U.S, the allies of Israel. Many more Beta Israel members crowded into refugee camps on the outskirts of Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, to escape the civil war raging in the north of Ethiopia (their region of origin), and await their turn to immigrate to Israel.

- May 24–25, 1991 (Operation Solomon)[11] – In 1991, the political and economic stability of Ethiopia deteriorated, as rebels mounted attacks against and eventually controlled the capital city of Addis Ababa. Worried about the fate of the Beta Israel during the transition period, the Israeli government, with the help of several private groups, resumed the migration. Over the course of 36 hours, a total of 34 El Al passenger planes, with their seats removed to maximize passenger capacity, flew 14,325 Beta Israel non-stop to Israel. Again, the operation was mainly carried out due to intervention and pressure from the U.S.

- 1992–1999 – During these years, the Qwara Beta Israel immigrated to Israel.

- 1997–present – In 1997, an irregular emigration began of Falash Mura, which was and still is mainly subject to political developments in Israel.

The difficulties of the Falash Mura in immigrating to Israel

In 1991, the Israeli authorities announced that the emigration of the Beta Israel to Israel was about to conclude, because almost all of the community had been evacuated. Nevertheless, thousands of other Ethiopians began leaving the northern region to take refuge in the government controlled capital, Addis Ababa, declaring themselves to be Jewish converts to Christianity and asking to immigrate to Israel. As a result, a new term arose which was used to refer to this group: "Falash Mura". The Falash Mura, who weren't part of the Beta Israel communities in Ethiopia, were not recognized as Jews by the Israeli authorities, and were therefore not initially allowed to immigrate to Israel, making them ineligible for Israeli citizenship under Israel's Law of Return.

As a result, a lively debate has arisen in Israel about the Falash Mura, mainly between the Beta Israel community in Israel and their supporters and those opposed to a potential massive emigration of the Falash Mura people. The government's position on the matter remained quite restrictive, but it has been subject to numerous criticisms, including criticisms by some clerics who want to encourage these people's return to Judaism.

During the 1990s, the Israeli government finally allowed most of those who fled to Addis Ababa to immigrate to Israel.[111] Some did so through the Law of Return, which allows an Israeli parent of a non-Jew to petition for his/her son or daughter to be allowed to immigrate to Israel. Others were allowed to immigrate to Israel as part of a humanitarian effort.

_-_PM_Yitzhak_Shamir_Greets_new_immigrants_from_Ethiopia.jpg)

The Israeli government hoped that admitting these Falash Mura would finally bring emigration from Ethiopia to a close, but instead prompted a new wave of Falash Mura refugees fleeing to Addis Ababa and demanding the right to immigrate to Israel. This led the Israeli government to harden its position on the matter in the late 1990s.

In February 2003, the Israeli government decided to accept Orthodox religious conversions in Ethiopia of Falash Mura by Israeli Rabbis, after which they can then immigrate to Israel as Jews. Although the new position is more open, and although the Israeli governmental authorities and religious authorities should in theory allow emigration to Israel of most of the Falash Mura wishing to do so (who are now acknowledged to be descendants of the Beta Israel community), in practice, however, that immigration remains slow, and the Israeli government continued to limit, from 2003 to 2006, immigration of Falash Mura to about 300 per month.

In April 2005, the Jerusalem Post stated that it had conducted a survey in Ethiopia, after which it was concluded that tens of thousands of Falash Mura still lived in rural northern Ethiopia.

On 14 November 2010 the Israeli cabinet approved a plan to allow an additional 8,000 Falash Mura to immigrate to Israel.[112]

On November 16, 2015 the Israeli cabinet unanimously voted in favor of allowing the last group of Falash Mura to immigrate over the next five years but their acceptance will be conditional on a successful Jewish conversion process, according to the Interior Ministry.[113] In April 2016 they announced a total of 10,300 people would be included in the latest round of Aliyah, over the following 5 years.[114]

Population

Ethiopian Jews in Israel

The Ethiopian Beta Israel community in Israel today comprises more than 121,000 people.[1] Most of this population are the descendants and the immigrants who came to Israel during "Operation Moses" (1984) and "Operation Solomon" (1991).[115] Civil war and famine in Ethiopia prompted the Israeli government to mount these dramatic rescue operations. The rescues were within the context of Israel's national mission to gather Diaspora Jews and bring them to the Jewish homeland. Some immigration has continued up until the present day. Today 81,000 Ethiopian Israelis were born in Ethiopia, while 38,500 or 32% of the community are native born Israelis.[12]

Over time, the Ethiopian Jews in Israel moved out of the government owned mobile home camps which they initially lived in and settled in various cities and towns throughout Israel, with the encouragement of the Israeli authorities who grant new immigrants generous government loans or low-interest mortgages.

Similarly to other groups of immigrant Jews who made aliyah to Israel, the Ethiopian Jews have had to overcome obstacles to integrate into Israeli society.[116] Initially the main challenges faced by the Ethiopian Jewish community in Israel arose from communication difficulties (most of the Ethiopian population could not read nor write in Hebrew, and many of the older members could not hold a simple conversation in Hebrew), and discrimination, including manifestations of racism, from some parts of Israeli society.[117] Unlike Russian immigrants, many of whom arrived educated and skilled, Ethiopian immigrants[118] came from an impoverished agrarian country, and were ill-prepared to work in a developed industrialized country.

Over the years there has been significant progress in the integration of young Beta Israels into Israeli society, primarily resulting from serving in the Israeli Defense Forces alongside other Israelis their age. This has led to an increase in opportunities for Ethiopian Jews after they are discharged from the army.[119]

Despite progress, Ethiopian Jews are still not well assimilated into Israeli-Jewish society. They remain, on average, on a lower economic and educational level than average Israelis. Also, while marriages between Jews of different backgrounds are very common in Israel, marriages between Ethiopians and non-Ethiopians are not very common. According to a 2009 study, 90% of Ethiopian-Israelis – 93% of men and 85% of women, are married to other Ethiopian-Israelis. A survey found that 57% of Israelis consider a daughter marrying an Ethiopian unacceptable and 39% consider a son marrying an Ethiopian to be unacceptable. Barriers to intermarriage have been attributed to sentiments in both the Ethiopian community and Israeli society generally.[120] A 2011 study showed that only 13% of high school students of Ethiopian origin felt "fully Israeli".[121]

Discrimination and racism against Israeli Ethiopians is still perpetuated. In May 2015 Israeli Ethiopians demonstrated in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem against racism, after a video was released, showing an Israeli soldier of Ethiopian descent that was brutally beaten up by the Israeli police. Interviewed students of Ethiopian origin affirm that they do not feel accepted in Israeli society, due to a very strong discrimination towards them.[122]

Converts

Falash Mura

Falash Mura is the name given to those of the Beta Israel community in Ethiopia who converted to Christianity under pressure from the mission during the 19th century and the 20th century. This term consists of Jews who did not adhere to Jewish law, as well as Jewish converts to Christianity, who did so either voluntarily or who were forced to do so.

Many Ethiopian Jews whose ancestors converted to Christianity have been returning to the practice of Judaism. The Israeli government can thus set quotas on their immigration and make citizenship dependent on their conversion to Orthodox Judaism.

Beta Abraham

Slaves

Slavery was practiced in Ethiopia as in much of Africa until it was formally abolished in 1942. After the slave was bought by a Jew, he went through Giyur and became property of his master.[123]

In popular culture

- The 2005 Israeli-French film "Go, Live, and Become" (Hebrew: תחייה ותהייה), directed by Romanian-born Radu Mihăileanu focuses on Operation Moses. The film tells the story of an Ethiopian Christian child whose mother has him pass as Jewish so he can immigrate to Israel and escape the famine looming in Ethiopia. The film was awarded the 2005 Best Film Award at the Copenhagen International Film Festival.

- Several prominent musicians and rappers are of Ethiopian origin.[124]

Monuments

National memorials to the Ethiopian Jews who died on their way to Israel are located in Kiryat Gat, and at the National Civil Cemetery of the State of Israel in Mount Herzl in Jerusalem.

Ethiopian Heritage Museum

In 2009, plans to establish an Ethiopian Heritage Museum dedicated to the heritage and culture of the Ethiopian Jewish community were unveiled in Rehovot. The museum will include a model of an Ethiopian village, an artificial stream, a garden, classrooms, an amphitheater, and a memorial to Ethiopian Zionist activists and Ethiopian Jews who died en route to Israel.[125]

Café Shahor Hazak

Strong Black Coffee ("Café Shahor Hazak"; קפה שחור חזק) is an Ethiopian-Israeli hip hop duo.[126][127][128][129] The duo were a nominee for the 2015 MTV Europe Music Awards Best Israeli Act award.

See also

References

- 1 2 Israel Central Bureau of Statistics: The Ethiopian Community in Israel

- ↑ "'Wings of the Dove' brings Ethiopia's Jews to Israel". JPost.com. The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ↑ Mozgovaya, Natasha (2008-04-02). "Focus U.S.A.-Israel News – Haaretz Israeli News source". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- ↑ For the meaning of the word "Beta" in the context of social/religious is "community", see James Quirin, The Evolution of the Ethiopian Jews, 2010, p. xxi

- ↑ Weil, Shalva (1997) "Collective Designations and Collective Identity of Ethiopian Jews", in Shalva Weil (ed.) Ethiopian Jews in the Limelight, Jerusalem: NCJW Research Institute for Innovation in Education, Hebrew University, pp. 35–48. (Hebrew)

- ↑ Weil, Shalva. (2012) "Ethiopian Jews: the Heterogeneity of a Group", in Grisaru, Nimrod and Witztum, Eliezer. Cultural, Social and Clinical Perspectives on Ethiopian Immigrants in Israel, Beersheba: Ben-Gurion University Press, pp. 1–17.

- ↑ Michael Corinaldi, Ethiopian Jewry: Identity and Tradition, Rubin Mass, 1988, pp. 186–188 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Weil, Shalva. (2008) "Zionism among Ethiopian Jews", in Hagar Salamon (ed.) Jewish Communities in the 19th and 20th Centuries: Ethiopia, Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute, pp. 187–200. (Hebrew)

- ↑ Weil, Shalva 2012 "Longing for Jerusalem Among the Beta Israel of Ethiopia", in Edith Bruder and Tudor Parfitt (eds.) African Zion: Studies in Black Judaism, Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 204–217.

- ↑ The Rescue of Ethiopian Jews 1978–1990 (Hebrew); "Ethiopian Immigrants and the Mossad Met" (Hebrew)

- 1 2 Weil, Shalva. (2011) "Operation Solomon 20 Years On", International Relations and Security Network (ISN).http://www.isn.ethz.ch/isn/Current-Affairs/ISN-Insights/Detail?ord538=grp1&ots591=eb06339b-2726-928e-0216-1b3f15392dd8&lng=en&id=129480&contextid734=129480&contextid735=129244&tabid=129244

- 1 2 , Ha'aretz

- ↑ James Bruce, Travels To Discover The Source Of The Nile in the Years 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772, and 1773 (in five Volumes), Vol. II, Printed by J. Ruthven for G. G. J. and J. Robinson, 1790, p. 485

- ↑ Malchijah-MRC. "Home". www.himchurch.org. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ↑ Hagar Salamon, The Hyena People – Ethiopian Jews in Christian Ethiopia, University of California Press, 1999, p.21

- 1 2 Dege-Müller, Sophia (2018-04-17). "Between Heretics and Jews: Inventing Jewish Identities in Ethiopia". Entangled Religions. 6 (0): 247–308. ISSN 2363-6696.

- 1 2 3 4 Quirun, The Evolution of the Ethiopian Jews, pp. 11–15; Aešcoly, Book of the Falashas, pp. 1–3; Hagar Salamon, Beta Israel and their Christian neighbors in Ethiopia: Analysis of key concepts at different levels of cultural embodiment, Hebrew University, 1993, pp. 69–77 (Hebrew); Shalva Weil, "Collective Names and Collective Identity of Ethiopian Jews" in Ethiopian Jews in the Limelight, Hebrew University, 1997, pp. 35–48

- ↑ Salamon, Beta Israel, p. 135, n. 20 (Hebrew)

- ↑ Weil, Shalva. (1989) The Religious Beliefs and Practices of Ethiopian Jews in Israel, 2nd edn, Jerusalem: NCJW Research Institute forInnovation in Education, Hebrew University. (Hebrew)

- ↑ Weninger, Stefan. 2005. "Gə῾əz." In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D–Ha: Vol. 2, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, 732–735. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- ↑ Shelemay, Music, p. 42

- ↑ Quirun 1992, p. 71

- ↑ Weil, Shalva 1998 'Festivals and Cyclical Events of theYear', (149–160) and 'Elementary School', (174–177) in John Harrison, Rishona Wolfert and Ruth Levitov (eds) Culture – Differences in the World and in Israel: A Reader in Sociology for Junior High Schools, University of Tel-Aviv: Institute of Social Research and Ministry of Education, PedagogicAdministration. (Hebrew)

- ↑ Aešcoly, Book of the Falashas, p. 56

- ↑ Aešcoly, Book of the Falashas, pp. 62–70 (Hebrew); Shelemay, Music, Ritual, and Falasha History, pp. 44–57; Leslau, Falasha Anthology, pp. xxviii–xxxvi; Quirun, The Evolution of the Ethiopian Jews, pp. 146–150

- ↑ see Rosh Chodesh

- ↑ see also Yom Kippur Katan

- ↑ Spolsky, Bernard (2014). The Languages of the Jews: A Sociolinguistic History. Cambridge University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-107-05544-5.

- 1 2 Weil, Shalva 1987 'An Elegy in Amharic on Dr. Faitlovitch' Pe’amim33: 125–127. (Hebrew)

- ↑ Wolf Leslau, "Introduction," to his Falasha Anthology, Translated from Ethiopic Sources (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1951), p. xliii. Also see Steven Kaplan, "A Brief History of the Beta Israel," in The Jews of Ethiopia: A People in Transition (Tel Aviv and New York: Beth Hatefutsoth and The Jewish Museum, 1986), p. 11. Kaplan writes there, "Scholars remain divided (about Beta Israel origins) ... It has been suggested, for example, that the Jews of Ethiopia are descendants of (1) the Ten Lost Tribes, especially the tribe ofg Dan; (2) Ethiopian Christians and pagans who assumed a Jewish identity; (3) Jewish immigrants from South Arabia (Yemen) who intermarried with the local population; or (4) Jewish immigrants from Egypt who intermarried with the local population." For more on the Mosaic and Danite claims of traditionalist Beta Israel, see Salo Baron, Social and Religious History of the Jews, Second Edition (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, and New York: Columbia University Press, 1983) Vol. XVIII: p. 373.

- ↑ Budge, Queen of Sheba, Kebra Negast, §§ 38–64.

- ↑ Weil, Shalva. 1991 The Changing Religious Tradition of Ethiopian Jews in Israel: a Teachers’ Guide, Jerusalem: The Ministry of Education & Culture & NCJW Research Institute for Innovation in Education, Hebrew University. (Hebrew)

- ↑ Abbink, "The Enigma of Esra'el Ethnogenesis: An Anthro-Historical Study," Cahiers d'Etudes africaines, 120, XXX-4, 1990, pp. 412–420.

- ↑ Jankowski, Königin von Saba, 65–71.

- ↑ Schoenberger, M. (1975). The Falashas of Ethiopia: An Ethnographic Study (Cambridge: Clare Hall, Cambridge University). Quoted in Abbink, Jon (1990). "The Enigma of Beta Esra'el Ethnogenesis. An Anthro-Historical Study" (PDF). Cahiers d'Études africaines. 30 (120): 397–449. doi:10.3406/cea.1990.1592.

- ↑ Budge, Queen of Sheba, Kebra Negast, chap. 61.

- ↑ Weil, Shalva. 1989 Beta Israel: A House Divided. Binghamton State University of New York, Binghamton, New York.

- ↑ The complete guide to the Bible by Stephan M. Miller, p. 175

- ↑ Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia: 1270–1527 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972), pp. 38–39

- ↑ Knud Tage Andersen, "The Queen of Habasha in Ethiopian History, Tradition and Chronology," Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 63, No. 1 (2000), p. 20.

- ↑ Wolf Leslau, "Introduction," to his Falasha Anthology, Translated from Ethiopic Sources (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1951), p. xliii. Also see Steven Kaplan, "A Brief History of the Beta Israel," in The Jews of Ethiopia: A People in Transition (Tel Aviv and New York: Beth Hatefutsoth and The Jewish Museum, 1986), p. 11.

- ↑ This helped persuade rabbinic authorities of the day regarding the validity of his practices, even if they differed from their own traditional teachings. On this, also see the remarkable testimony of Hasdai ibn Shaprut, the Torah scholar and princely Jew of Cordoba, concerning Eldad's learning, in his letter to Joseph, King of the Khazars, around 960 CE., reproduced in Franz Kobler, ed., Letters of Jews Through the Ages, Second Edition (London: East and West Library, 1953), vol. 1: p. 105.

- ↑ See, in Eldad's letter recounting his experiences in Elkan N. Adler, ed., Jewish Travellers in the Middle Ages: 19 Firsthand Accounts (New York: Dover, 1987), p. 9.

- ↑ Eldad's letter recounting his experiences in Elkan N. Adler, ed., Jewish Travellers in the Middle Ages: 19 Firsthand Accounts (New York: Dover, 1987), pp. 12–14.

- ↑ See Salo Baron, Social and Religious History of the Jews, Second Edition (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1983), Vol. XVIII: 372.

- ↑ Also see the testimony of James Bruce, Travels in Abyssinia, 1773, which repeats these accounts of Mosaic antiquity for the Beta Israel.

- ↑ Archived August 20, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ See also the reference already cited from Hasdai ibn Shaprut, above.

- ↑ Steven Kaplan, "Eldad Ha-Dani", in Siegbert von Uhlig, ed., Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), p. 252. Medieval travellers' accounts typically are vague in such matters, and are not presented as geographical treatises; moreover, Ethiopians, Sudanese and Somalians do not all know all the tribal languages around them. In earlier times, the different ethnic groups would have been even more insular. In any case, the "Letter of Eldad the Danite" summarized his experiences.

- ↑ Avraham Ya'ari, Igrot Eretz Yisrael, Ramat Gan: 1971.

- ↑ Weil, Shalva. 1991 Beyond the Sambatyon: the Myth of the Ten Lost Tribes, Tel-Aviv: Beth Hatefutsoth, the Nahum Goldman Museum of the Jewish Diaspora.

- ↑ Responsum of the Radbaz on the Falasha Slave, Part 7. No. 5, cited in Corinaldi, 1998: 196.

- ↑ "The History of Ethiopian Jews". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- ↑ Rabbi Eliezer Waldenberg, Tzitz Eliezer, Volume 17, subject 48, page 105.

- ↑ Michael Ashkenazi, Alex Weingrod. Ethiopian Jews and Israel, Transaction Publishers, 1987, p. 30, footnote 4.

- ↑ Rabbi Eliezer Waldenberg, Tzitz Eliezer, p. 104

- ↑ Ruth Karola Westheimer, Steven Kaplan. Surviving Salvation: The Ethiopian Jewish Family in Transition, NYU Press, 1992, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ איינאו פרדה סנבטו, Operation Moshe Archived 2008-01-22 at the Wayback Machine., מוסף Haaretz 11.3.2006

- ↑ Israel Association for Ethiopian Jews, דו"ח מעקב – סוגיית זכאותם לעלייה של בני הפלשמורה Archived 2012-11-09 at the Wayback Machine., 21 January 2008, p. 9

- ↑ Netta Sela, הרב עמאר:הלוואי ויעלו מיליוני אתיופים לארץ, ynet, 16 January 2008

- ↑ Emanuela Trevisan Semi, Tudor Parfitt. Jews of Ethiopia: The Birth of an Elite, Routledge, 2005, p. 139.

- ↑ Trombetta, Beniamino; Cruciani, Fulvio; Sellitto, Daniele; Scozzari, Rosaria (2011-01-06). "A new topology of the human Y chromosome haplogroup E1b1 (E-P2) revealed through the use of newly characterized binary polymorphisms". PLOS One. 6 (1): e16073. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016073. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3017091. PMID 21253605.

- ↑ https://www.yfull.com/tree/E-M329/

- ↑ Llorente, M. Gallego; Jones, E. R.; Eriksson, A.; Siska, V.; Arthur, K. W.; Arthur, J. W.; Curtis, M. C.; Stock, J. T.; Coltorti, M. (2015-11-13). "Ancient Ethiopian genome reveals extensive Eurasian admixture in Eastern Africa". Science. 350 (6262): 820–822. doi:10.1126/science.aad2879. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 26449472.

- ↑ Plaster et al. Y-DNA E subclades

- ↑ C.A., Plaster, (2011-09-28). "Variation in Y chromosome, mitochondrial DNA and labels of identity on Ethiopia". discovery.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-06-27.

- ↑ Cruciani F, Santolamazza P, Shen P, et al. (May 2002). "A back migration from Asia to sub-Saharan Africa is supported by high-resolution analysis of human Y-chromosome haplotypes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (5): 1197–214. doi:10.1086/340257. PMC 447595. PMID 11910562.

- ↑ Rosenberg, N. A.; Woolf, E; Pritchard, JK; Schaap, T; Gefel, D; Shpirer, I; Lavi, U; Bonne-Tamir, B; et al. (2001). "Distinctive genetic signatures in the Libyan Jews". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (3): 858–63. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.3.858. PMC 14674. PMID 11158561.

- ↑ Tishkoff, S. A.; Reed, F. A.; Friedlaender, F. R.; Ehret, C.; Ranciaro, A.; Froment, A.; Hirbo, J. B.; Awomoyi, A. A.; et al. (2009). "The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans" (PDF). Science. 324 (5930): 1035–44. doi:10.1126/science.1172257. PMC 2947357. PMID 19407144.