New Kingdom of Egypt

| New Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1550 BC – c. 1077 BC | |||||||||||||||||

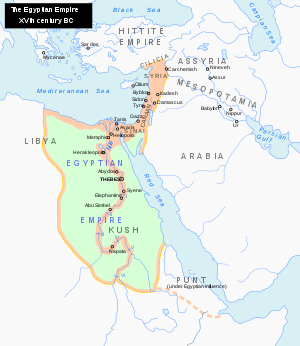

New Kingdom at its maximum territorial extent in the 15th century BC. | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Ancient Egyptian, Nubian, Canaanite | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Divine absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||

• c. 1550 BC – c. 1525 BC | Ahmose I (first) | ||||||||||||||||

• c. 1107 BC – c. 1077 BC | Ramesses XI (last) | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Established | c. 1550 BC | ||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 1077 BC | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Dynasties of Ancient Egypt | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All years are BC | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

See also: List of Pharaohs by Period and Dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||

The New Kingdom, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire, is the period in ancient Egyptian history between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC, covering the 18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties of Egypt. Radiocarbon dating places the exact beginning of the New Kingdom between 1570 BC and 1544 BC.[1] The New Kingdom followed the Second Intermediate Period and was succeeded by the Third Intermediate Period. It was Egypt's most prosperous time and marked the peak of its power.[2]

The later part of this period, under the 19th and 20th Dynasties (1292–1069 BC), is also known as the Ramesside period. It is named after the 11 Pharaohs that took the name Ramesses, after Ramesses I, the founder of the 19th Dynasty.[2]

Possibly as a result of the foreign rule of the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period, the New Kingdom saw Egypt attempt to create a buffer between the Levant and Egypt proper, and during this time Egypt attained its greatest territorial extent. Similarly, in response to very successful 17th century attacks during the Second Intermediate Period by the powerful Kingdom of Kush,[3] the rulers of the New Kingdom felt compelled to expand far south into Nubia and to hold wide territories in the Near East. In the north, Egyptian armies fought Hittite armies for control of modern-day Syria.

History

Rise of the New Kingdom

The 18th Dynasty included some of Egypt's most famous Pharaohs, including Ahmose I, Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, Akhenaten and Tutankhamun. Queen Hatshepsut concentrated on expanding Egypt's external trade by sending a commercial expedition to the land of Punt.

Thutmose III ("the Napoleon of Egypt") expanded Egypt's army and wielded it with great success to consolidate the empire created by his predecessors. This resulted in a peak in Egypt's power and wealth during the reign of Amenhotep III. During the reign of Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BC), the term Pharaoh, originally referring to the king's palace, became a form of address for the person who was king.[4]

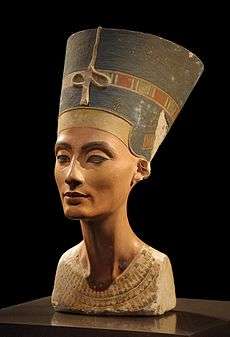

One of the best-known 18th Dynasty pharaohs is Amenhotep IV, who changed his name to Akhenaten in honor of the Aten, a representation of the Egyptian god, Ra. His exclusive worship of the Aten is often interpreted as history's first instance of monotheism. Akhenaten's wife, Nefertiti, contributed a great deal to his new take on the Egyptian religion. Nefertiti was bold enough to perform rituals to Aten. Akhenaten's religious fervor is cited as the reason why he and his wife were subsequently written out of Egyptian history.[5] Under his reign, in the 14th century BC, Egyptian art flourished in a distinctive new style. (See Amarna Period.)

By the end of the 18th Dynasty, Egypt's status had changed radically. Aided by Akhenaten's apparent lack of interest in international affairs, the Hittites had gradually extended their influence into Phoenicia and Canaan to become a major power in international politics — a power that both Seti I and his son Ramesses II would confront during the 19th Dynasty.

Height of the New Kingdom

The Nineteenth Dynasty was founded by the Vizier Ramesses I, whom the last ruler of the 18th dynasty, Pharaoh Horemheb, had chosen as his successor. His brief reign marked a transition period between the reign of Horemheb and the powerful pharaohs of this dynasty, in particular, his son Seti I and grandson Ramesses II, who would bring Egypt to new heights of imperial power.

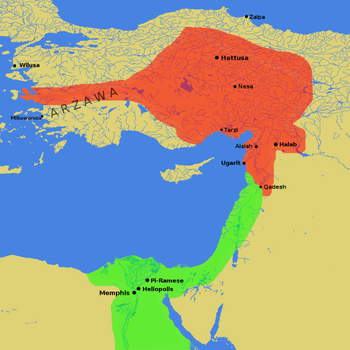

Ramesses II ("the Great") sought to recover territories in the Levant that had been held by the 18th Dynasty. His campaigns of reconquest culminated in the Battle of Kadesh, where he led Egyptian armies against those of the Hittite king Muwatalli II. Ramesses was caught in history's first recorded military ambush, although he was able to rally his troops and turn the tide of battle against the Hittites thanks to the arrival of the Ne'arin (possibly mercenaries in the employ of Egypt). The outcome of the battle was undecided, with both sides claiming victory at their home front, and ultimately resulting in a peace treaty between the two nations. Egypt was able to obtain wealth and stability under Ramesses' rule of over half a century.[6] His immediate successors continued the military campaigns, although an increasingly troubled court—which at one point put a usurper (Amenmesse) on the throne—made it increasingly difficult for a pharaoh to effectively retain control of the territories.

Ramesses II was also famed for the huge number of children he sired by his various wives and concubines; the tomb he built for his sons, many of whom he outlived, in the Valley of the Kings has proven to be the largest funerary complex in Egypt.

Egyptian and Hittite Empires, around the time of the Battle of Kadesh.

Egyptian and Hittite Empires, around the time of the Battle of Kadesh.

Final years of power

The last "great" pharaoh from the New Kingdom is widely considered to be Ramesses III, a 20th Dynasty pharaoh who reigned several decades after Ramesses II.[7]

In the eighth year of his reign the Sea Peoples invaded Egypt by land and sea. Ramesses III defeated them in two great land and sea battles (the Battle of Djahy and the Battle of the Delta). He incorporated them as subject peoples and settled them in Southern Canaan although there is evidence that they forced their way into Canaan. Their presence in Canaan may have contributed to the formation of new states, such as Philistia, in this region after the collapse of the Egyptian Empire. He was also compelled to fight invading Libyan tribesmen in two major campaigns in Egypt's Western Delta in his sixth year and eleventh year respectively.[8]

The heavy cost of this warfare slowly drained Egypt's treasury and contributed to the gradual decline of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. The severity of the difficulties is indicated by the fact that the first known labor strike in recorded history occurred during the 29th year of Ramesses III's reign, when the food rations for Egypt's favored and elite royal tomb-builders and artisans in the village of Deir el Medina could not be provisioned.[9] Air pollutants prevented much sunlight from reaching the ground and also arrested global tree growth for almost two full decades until 1140 BC.[10] One proposed cause is the Hekla 3 eruption of the Hekla volcano in Iceland but the dating of this remains disputed.

Decline into the Third Intermediate Period

Rameses III's death was followed by years of bickering among his heirs. Three of his sons ascended the throne successively as Ramesses IV, Rameses VI and Rameses VIII. Egypt was increasingly beset by droughts, below-normal flooding of the Nile, famine, civil unrest and official corruption. The power of the last pharaoh of the dynasty, Ramesses XI, grew so weak that in the south the High Priests of Amun at Thebes became the de facto rulers of Upper Egypt, and Smendes controlled Lower Egypt even before Rameses XI's death. Smendes eventually founded the 21st Dynasty at Tanis.

Gallery

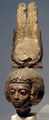

Relief of a Nobleman, c. 1295–1070 B.C.E. Brooklyn Museum

Relief of a Nobleman, c. 1295–1070 B.C.E. Brooklyn Museum- Queen Ahmose-Nefertari

Hatshepsut as a Sphinx. Daughter of Thutmose I, she ruled jointly as her stepson's (Thutmose III) co-regent. She soon took the throne for herself, and declared herself pharaoh.

Hatshepsut as a Sphinx. Daughter of Thutmose I, she ruled jointly as her stepson's (Thutmose III) co-regent. She soon took the throne for herself, and declared herself pharaoh.- Queen Hatshepsut's Temple at Deir el-Bahari, was called Djeser-Djeseru, meaning the Holy of Holies, in ancient times.

Thutmosis III, a military man and member of the Thutmosid royal line is commonly called the Napoleon of Egypt. His conquests of the Levant brought Egypt's territories and influence to its greatest extent.

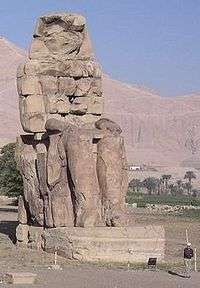

Thutmosis III, a military man and member of the Thutmosid royal line is commonly called the Napoleon of Egypt. His conquests of the Levant brought Egypt's territories and influence to its greatest extent. Colossi of Memnon. Representing Amenhotep III, this statue sits outside Luxor.

Colossi of Memnon. Representing Amenhotep III, this statue sits outside Luxor. Tiye, born a commoner, became queen through her marriage to Amenhotep III. In the New Kingdom, women gained influence in court, and Tiye soon helped run affairs of state for both her husband and son during their reigns.

Tiye, born a commoner, became queen through her marriage to Amenhotep III. In the New Kingdom, women gained influence in court, and Tiye soon helped run affairs of state for both her husband and son during their reigns.- Akhenaten, born Amenhotep IV, was the son of Queen Tiye. He rejected the old Egyptian religion and went about promoting the Aten as a supreme deity.

Akhenaten

Akhenaten Bust of Nefertiti. The wife of Akhenaten, she held position as co-regent with Akhenaten. She may also have ruled as pharaoh in her own right as she is one of few candidates for the identity of Pharaoh Neferneferuaten.

Bust of Nefertiti. The wife of Akhenaten, she held position as co-regent with Akhenaten. She may also have ruled as pharaoh in her own right as she is one of few candidates for the identity of Pharaoh Neferneferuaten. Tutankhamun's mask. King Tutankhamun, son of Akhenaten, restored Egypt to its former religion. Though he died young and was not considered significant in his own time, the 1922 discovery of his KV62 intact tomb by Howard Carter, made him relevant as a symbol of ancient Egypt in the modern world.

Tutankhamun's mask. King Tutankhamun, son of Akhenaten, restored Egypt to its former religion. Though he died young and was not considered significant in his own time, the 1922 discovery of his KV62 intact tomb by Howard Carter, made him relevant as a symbol of ancient Egypt in the modern world.- Detail Temple of Rameses II

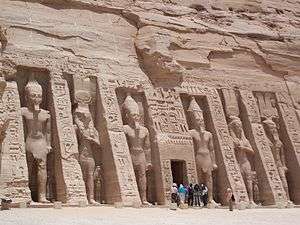

Nefertari's Temple at Abu Simbel

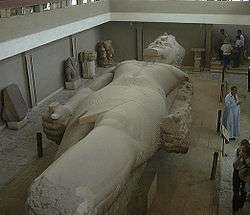

Nefertari's Temple at Abu Simbel Giant Ramses II

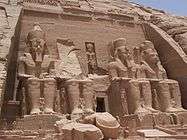

Giant Ramses II Abu Simbel Temple of Ramesses II

Abu Simbel Temple of Ramesses II- Abu Simbel

King Tutanhkamun Guardian Statue

King Tutanhkamun Guardian Statue

See also

References

- ↑ Christopher Bronk Ramsey et al., Radiocarbon-Based Chronology for Dynastic Egypt, Science 18 June 2010: Vol. 328, no. 5985, pp. 1554–1557.

- 1 2 Shaw, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 481. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- ↑ Alberge, Dalya. "Tomb reveals Ancient Egypt's humiliating secret". The Times. London. Retrieved June 14, 2017. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Redmount, Carol A. "Bitter Lives: Israel in and out of Egypt." p. 89-90. The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Michael D. Coogan, ed. Oxford University Press. 1998.

- ↑ Tyldesley, Joyce (2005-04-28). Nefertiti: Egypt's Sun Queen. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141949796.

- ↑ Thomas, Susanna (2003). Rameses II: Pharaoh of the New Kingdom. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 9780823935970.

- ↑ Eric H. Cline and David O'Connor, eds. Ramesses III: The Life and Times of Egypt's Last Hero (University of Michigan Press; 2012)

- ↑ Nicolas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Books, 1992. p.271

- ↑ William F. Edgerton, "The Strikes in Ramses III's Twenty-Ninth Year", JNES 10, no. 3 (July 1951), pp. 137–145.

- ↑ Frank J. Yurco, "End of the Late Bronze Age and Other Crisis Periods: A Volcanic Cause," in Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente, ed: Emily Teeter & John Larson, (SAOC 58) 1999, pp. 456-458.

Further reading

- Bierbrier, M. L. The Late New Kingdom In Egypt, C. 1300-664 B.C.: A Genealogical and Chronological Investigation. Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips, 1975.

- Freed, Rita A., Yvonne Markowitz, and Sue H. d’Auria, eds. Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamun. London: Thames & Hudson, 1999.

- Freed, Rita E. Egypt's Golden Age: The Art of Living In the New Kingdom, 1558-1085 B.C. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1981.

- Kemp, Barry J. The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and Its People. London: Thames & Hudson, 2012.

- Morkot, Robert. A Short History of New Kingdom Egypt. London: Tauris, 2015.

- Radner, Karen. State Correspondence In the Ancient World: From New Kingdom Egypt to the Roman Empire. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Redford, Donald B. Egypt and Canaan In the New Kingdom. Beʾer Sheva: Ben Gurion University of the Negev Press, 1990.

- Sadek, Ashraf I. Popular Religion In Egypt During the New Kingdom. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg, 1987.

- Spalinger, Anthony John. War In Ancient Egypt: The New Kingdom. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., 2005.

- Thomas, Angela P. Akhenaten’s Egypt. Shire Egyptology 10. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire, 1988.

- Tyldesley, Joyce A. Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom. London: Headline Book Pub., 2001.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Egyptian New Kingdom. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Egyptian Empire. |

| Library resources about New Kingdom of Egypt |

- Middle East on the Matrix: Egypt, The New Kingdom—Photographs of many of the historic sites dating from the New Kingdom

- New Kingdom of Egypt - Aldokkan