Dome of the Rock

| Dome of the Rock | |

|---|---|

|

Qubbat As-Sakhrah قبّة الصخرة | |

-Jerusalem-Temple_Mount-Dome_of_the_Rock_(SE_exposure).jpg) | |

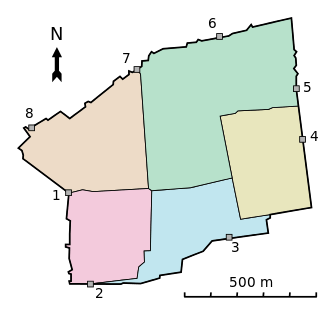

Location within the Old City of Jerusalem | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Jerusalem |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°46′41″N 35°14′07″E / 31.7780°N 35.2354°ECoordinates: 31°46′41″N 35°14′07″E / 31.7780°N 35.2354°E |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Administration | Ministry of Awqaf (Jordan) |

| Architectural description | |

| Architectural type | Shrine |

| Architectural style | Umayyad, Abbasid, Ottoman |

| Date established | built 688–692,[1] expanded 820s, restored 1020s, 1545–1566, 1721/2, 1817, 1874/5, 1959–1962, 1993. |

| Specifications | |

| Dome(s) | 1 |

| Minaret(s) | 0 |

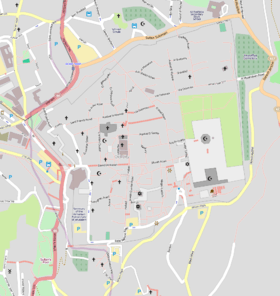

The Dome of the Rock (Arabic: قبة الصخرة Qubbat al-Sakhrah, Hebrew: כיפת הסלע Kippat ha-Sela) is an Islamic shrine located on the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem.

It was initially completed in 691 CE at the order of Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik during the Second Fitna, built on the site of the Roman temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, which had in turn been built on the site of the Second Jewish Temple, destroyed during the Roman Siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE. The original dome collapsed in 1015 and was rebuilt in 1022–23. The Dome of the Rock is in its core one of the oldest extant works of Islamic architecture.[2]

Its architecture and mosaics were patterned after nearby Byzantine churches and palaces,[3] although its outside appearance has been significantly changed in the Ottoman period and again in the modern period, notably with the addition of the gold-plated roof, in 1959–61 and again in 1993. The octagonal plan of the structure may have been influenced by the Byzantine Church of the Seat of Mary (also known as Kathisma in Greek and al-Qadismu in Arabic) built between 451 and 458 on the road between Jerusalem and Bethlehem.[3]

The site's great significance for Muslims derives from traditions connecting it to the creation of the world and to the belief that the Prophet Muhammad's Night Journey to heaven started from the rock at the center of the structure.[4][5]

In Jewish tradition the rock bears great significance as the Foundation Stone, the place from which the world expanded into its present form and where God gathered the dust used to create the first human, Adam;[6] as the site on Mount Moriah where Abraham attempted to sacrifice his son; and as the place where God's divine presence is manifested more than in any other place, towards which Jews turn during prayer.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site, it has been called "Jerusalem's most recognizable landmark,"[7] along with two nearby Old City structures, the Western Wall, and the "Resurrection Rotunda" in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[8]

History

Pre-Islamic

The Dome of the Rock is situated in the center of the Temple Mount, the site of the Temple of Solomon and the Jewish Second Temple, which had been greatly expanded under Herod the Great in the 1st century BCE. Herod's Temple was destroyed in 70 CE by the Romans, and after the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 CE, a Roman temple to Jupiter Capitolinus was built at the site.[9]

Jerusalem was ruled by the Christian Byzantine Empire throughout the 4th to 6th centuries. During this time, Christian pilgrimage to Jerusalem began to develop.[10] The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built under Constantine in the 320s, but the Temple Mount was left undeveloped after a failed project of restoration of the Jewish Temple under Julian the Apostate.[11]

Original construction

The Dome of the Rock is now mostly assumed to have been built by the order of Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik and his son and successor Al-Walid I. According to Sibt ibn al-Jawzi, construction started in 687. Construction cost was reportedly seven times the yearly tax income of Egypt.[12]

A dedicatory inscription in Kufic script is preserved inside the dome. The date is recorded as AH 72 (691/2 CE), the year historians believe the construction of the original Dome was completed.[13] In this inscription, the name of al-Malik was deleted and replaced by the name of Abbasid caliph Al-Ma'mun. This alteration of the original inscription was first noted by Melchior de Vogüé in 1864.[14] Some scholars have suggested that the dome was added to an existing building, built either by Muawiyah I (r. 661–680),[15] or indeed a Byzantine building dating to before the Muslim conquest, built under Heraclius (r. 610–641).[16]

Its architecture and mosaics were patterned after nearby Byzantine churches and palaces.[3] The two engineers in charge of the project were Raja ibn Haywah, a Muslim theologian from Beit She'an and Yazid Ibn Salam, a non-Arab who was Muslim and a native of Jerusalem.[3][17]

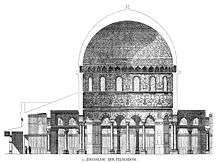

Shelomo Dov Goitein of the Hebrew University has argued that the Dome of the Rock was intended to compete with the many fine buildings of worship of other religions: "The very form of a rotunda, given to the Qubbat as-Sakhra, although it was foreign to Islam, was destined to rival the many Christian domes."[19] K.A.C. Creswell in his book The Origin of the Plan of the Dome of the Rock notes that those who built the shrine used the measurements of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The diameter of the dome of the shrine is 20.20 m (66.3 ft) and its height 20.48 m (67.2 ft), while the diameter of the dome of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is 20.90 m (68.6 ft) and its height 21.05 m (69.1 ft).

The structure was basically octagonal. It comprised a wooden dome, approximately 20 m (66 ft) in diameter, which was mounted on an elevated drum consisting of a circle of 16 piers and columns.[20] Surrounding this circle was an octagonal arcade of 24 piers and columns.

Abbasids and Fatimids

The building was severely damaged by earthquakes in 808 and again in 846.[21] The dome collapsed in an earthquake in 1015 and was rebuilt in 1022–23. The mosaics on the drum were repaired in 1027–28.[22]

Crusaders

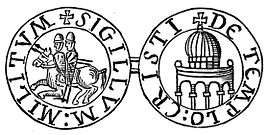

For centuries Christian pilgrims were able to come and experience the Temple Mount, but escalating violence against pilgrims to Jerusalem (Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, who ordered the destruction of the Holy Sepulchre, was an example) instigated the Crusades.[23] The Crusaders captured Jerusalem in 1099 and the Dome of the Rock was given to the Augustinians, who turned it into a church, while the Al-Aqsa Mosque became a royal palace. The Knights Templar, active from c. 1119, identified the Dome of the Rock as the site of the Temple of Solomon and set up their headquarters in the Al-Aqsa Mosque adjacent to the Dome for much of the 12th century. The Templum Domini, as they called the Dome of the Rock, featured on the official seals of the Order's Grand Masters (such as Everard des Barres and Renaud de Vichiers), and soon became the architectural model for round Templar churches across Europe.

Ayyubids and Mamluks

Jerusalem was recaptured by Saladin on 2 October 1187, and the Dome of the Rock was reconsecrated as a Muslim shrine. The cross on top of the dome was replaced by a crescent, and a wooden screen was placed around the rock below. Saladin's nephew al-Malik al-Mu'azzam Isa carried out other restorations within the building, and added the porch to the Al-Aqsa Mosque.

The Dome of the Rock was the focus of extensive royal patronage by the sultans during the Mamluk period, which lasted from 1250 until 1510.

Ottoman Empire (1517–1917)

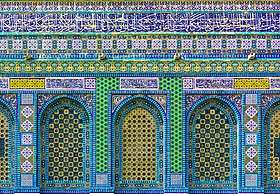

During the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566) the exterior of the Dome of the Rock was covered with tiles. This work took seven years.

The interior of the dome is lavishly decorated with mosaic, faience and marble, much of which was added several centuries after its completion. It also contains Qur'anic inscriptions. Surah Ya Sin (the "Heart of the Quran") is inscribed across the top of the tile work and was commissioned in the 16th century by Suleiman the Magnificent. Al-Isra, the Surah 17 which tells the story of the Isra or Night Journey, is inscribed above this.

Adjacent to the Dome of the Rock, the Ottomans built the free-standing Dome of the Prophet in 1620. Large-scale renovation was undertaken during the reign of Mahmud II in 1817.

In a major restoration project undertaken in 1874–75 during the reign of the Ottoman Sultan Abdülaziz, all the tiles on the west and southwest walls of the octagonal part of the building were removed and replaced by copies that had been made in Turkey.[24][25]

The first-ever photograph of the building, 1842–44

The first-ever photograph of the building, 1842–44 View from the north, Francis Bedford (1862)

View from the north, Francis Bedford (1862) West front in 1862. By this date many of the 16th century tiles were missing.

West front in 1862. By this date many of the 16th century tiles were missing. Interior showing mosaic decoration (1914)

Interior showing mosaic decoration (1914) Tiled façade (2013)

Tiled façade (2013) Interior showing rock (1915)

Interior showing rock (1915)

Modern history

Haj Amin al-Husseini, appointed Grand Mufti by the British during the 1917 mandate of Palestine, along with Yaqub al-Ghusayn, implemented the restoration of the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.

The Dome of the Rock was badly shaken during the 11 July 1927 Jericho earthquake, damaging many of the repairs that had taken place over previous years.

In 1955, an extensive program of renovation was begun by the government of Jordan, with funds supplied by Arab governments and Turkey. The work included replacement of large numbers of tiles dating back to the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, which had become dislodged by heavy rain. In 1965, as part of this restoration, the dome was covered with a durable aluminium bronze alloy made in Italy that replaced the lead exterior. Before 1959, the dome was covered in blackened lead. In the course of substantial restoration carried out from 1959 to 1962, the lead was replaced by aluminum-bronze plates covered with gold leaf.

A few hours after the Israeli flag was hoisted over the Dome of the Rock in 1967 during the Six-Day War, Israelis lowered it on the orders of Moshe Dayan and invested the Muslim waqf (religious trust) with the authority to manage the Temple Mount / Haram al-Sharif, in order to "keep the peace".[26]

In 1993, the golden dome covering was refurbished following a donation of USD 8.2 million by King Hussein of Jordan who sold one of his houses in London to fund the 80 kilograms of gold required.

The Dome of the Rock has been depicted on the Obverse and reverse of several Middle East currencies:

Reverse of a 1,000 Iranian rial banknote (1992).

Reverse of a 1,000 Iranian rial banknote (1992). Reverse of a 1 Jordanian dinar banknote (1959). Since 1992, the 20 Dinar note bears the Dome's depiction.

Reverse of a 1 Jordanian dinar banknote (1959). Since 1992, the 20 Dinar note bears the Dome's depiction.-donatedth_f.jpg) Obverse of a 50 Saudi riyal banknote (1983).

Obverse of a 50 Saudi riyal banknote (1983). Reverse of a 250 Iraqi dinar banknote (2002).

Reverse of a 250 Iraqi dinar banknote (2002). Obverse of a 1 Palestinian pound banknote (1939).

Obverse of a 1 Palestinian pound banknote (1939).

Accessibility

The Dome is maintained by the Ministry of Awqaf in Amman, Jordan.[27]

Until the mid-twentieth century, non-Muslims were not permitted in the area. Since 1967, non-Muslims have been permitted limited access; however non-Muslims are not permitted to pray on the Temple Mount, bring prayer books, or wear religious apparel. The Israeli police help enforce this.[28] Israel restricted access for a short time during 2012 of Palestinian residents of the West Bank to the Temple Mount. West Bank Palestinian men had to be over 35 to be eligible for a permit.[29] Palestinian residents of Jerusalem, who hold Israeli residency cards, and Palestinians with Israeli citizenship are permitted unrestricted access.

Some Orthodox rabbis encourage Jews to visit the site, while most forbid entry to the compound lest there be a violation of Jewish law. Even rabbis who encourage entrance to the Temple Mount prohibit entrance to the actual Dome of the Rock.[30]

Religious significance

According to some Islamic scholars, the rock is the spot[31] from which the Islamic prophet Muhammad ascended to Heaven accompanied by the angel Gabriel. Further, Muhammad was taken here by Gabriel to pray with Abraham, Moses, and Jesus.[32] Other Islamic scholars believe that the Prophet ascended to Heaven from the Al-Aqsa Mosque.[33][34]

Muslims believe the location of the Dome of the Rock to be the site mentioned in Sura 17 of the Qur'an, which tells the story of the Isra and Mi'raj, the miraculous Night Journey of Prophet Muhammad from Mecca to "the farthest mosque", where he leads prayers and rises to heaven to receive instructions from Allah. The Night Journey is mentioned in the Qur'an in a very brief form and is further elaborated by the hadiths. Caliph Umar ibn Al-Khattab (579–644) was advised by Ka'ab al-Ahbar, a Jewish rabbi who converted to Islam,[35] that "the farthest mosque" is identical with the site of the former Jewish Temples in Jerusalem.

The Foundation Stone and its surroundings is the holiest site in Judaism. Though Muslims now pray towards the Kaaba at Mecca, they once faced the Temple Mount as the Jews do. Muhammad changed the direction of prayer for Muslims after a revelation from Allah. Jews traditionally regarded the location of the stone as the holiest spot on Earth, the site of the Holy of Holies during the Temple Period.

According to Jewish tradition, the stone is the site where Abraham prepared to sacrifice his son Isaac.

On the walls of the Dome of the Rock is an inscription in a mosaic frieze that includes an explicit rejection of the divinity of Christ, from Quran (19:33–35):

33. "So peace is upon me the day I was born, and the day I die, and the day I shall be raised alive!" 34. Such is Jesus, son of Mary. It is a statement of truth, about which they doubt. 35. It is not befitting to (the majesty of) Allah that He should take himself a child. Glory be to Him! when He determines a matter, He only says to it, "Be", and it is.

According to Goitein, the inscriptions decorating the interior clearly display a spirit of polemic against Christianity, whilst stressing at the same time the Qur'anic doctrine that Jesus was a true prophet. The formula la sharika lahu ("God has no companion") is repeated five times; the verses from Sura Maryam 19:35–37, which strongly reaffirm Jesus' prophethood to God, are quoted together with the prayer: Allahumma salli ala rasulika wa'abdika 'Isa bin Maryam – "O Lord, send your blessings to your Prophet and Servant Jesus son of Mary." He believes that this shows that rivalry with Christendom, together with the spirit of Muslim mission to the Christians, was at work at the time of construction.[19]

The Temple Institute wishes to relocate the Dome to another site and replace it with a Third Temple.[36] Many Israelis are ambivalent about the Movement's wishes. Some religious Jews, following rabbinic teaching, believe that the Temple should only be rebuilt in the messianic era, and that it would be presumptuous of people to force God's hand. However, some Evangelical Christians consider rebuilding of the Temple to be a prerequisite to Armageddon and the Second Coming.[37] Jeremy Gimpel, a US-born candidate for Habayit Hayehudi in the 2013 Israeli elections, caused a controversy when he was recorded telling a Fellowship Church evangelical group in Florida in 2011 to imagine the incredible experience that would follow were the Dome to be destroyed. All Christians would be immediately transported to Israel, he opined.[38]

Architectural homages

The Dome of the Rock has inspired the architecture of a number of buildings. These include the octagonal Church of St. Giacomo in Italy, the Mausoleum of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in Istanbul, the octagonal Moorish Revival style Rumbach Street Synagogue in Budapest, and the New Synagogue in Berlin, Germany. It was long believed by Christians that the Dome of the Rock echoed the architecture of the Temple in Jerusalem, as can be seen in Raphael's The Marriage of the Virgin and in Perugino's Marriage of the Virgin.[39]

Images

_02.jpg) The Interior of the Dome

The Interior of the Dome_1.jpg) The Dome itself

The Dome itself Ornaments and writing inside the Dome

Ornaments and writing inside the Dome More detailed image

More detailed image_3.jpg) Foundation stone of the Dome

Foundation stone of the Dome Interior Vector

Interior Vector

See also

Notes

- ↑ Gil, Moshe (1997). A History of Palestine, 634–1099. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59984-9.

- ↑ Slavik, Diane (2001). Cities through Time: Daily Life in Ancient and Modern Jerusalem. Geneva, Illinois: Runestone Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8225-3218-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Avner, Rina (2010). "The Dome of the Rock in light of the development of concentric martyria in Jerusalem" (PDF). Muqarnas. Volume 27: An Annual on the Visual Cultures of the Islamic World. Leiden: Brill. pp. 31–50 [43–44]. ISBN 978-900418511-1. JSTOR 25769691.

- ↑ M. Anwarul Islam and Zaid F. Al-hamad (2007). "The Dome of the Rock: Origin of its octagonal plan". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 139 (2): 109–128.

- ↑ Nasser Rabbat (1989). "The meaning of the Umayyad Dome of the Rock". Muqarnas. 6: 12–21.

- ↑ Carol Delaney, Abraham on Trial: The Social Legacy of Biblical Myth, Princeton University Press 2000 p.120.

- ↑ Goldberg, Jeffrey (29 January 2001). "Arafat's Gift". The New Yorker. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ "UNESCO World Heritage".

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aelia Capitolina". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 256. Lester L. Grabbe (2010). An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel, and Jesus. A&C Black. p. 29.

- ↑ Davidson, Linda Kay and David Martin Gitlitz Pilgrimage: From the Ganges to Graceland : an Encyclopedia Volume 1, ABC-CLIO, Inc, Santa Barbara, CA 2002, p. 274.

- ↑ "Julian thought to rebuild at an extravagant expense the proud Temple once at Jerusalem, and committed this task to Alypius of Antioch. Alypius set vigorously to work, and was seconded by the governor of the province, when fearful balls of fire, breaking out near the foundations, continued their attacks, till the workmen, after repeated scorchings, could approach no more: and he gave up the attempt." Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 23.1.2–3.

- ↑ Jacob Lassner: Muslims on the sanctity of Jerusalem: preliminary thoughts on the search for a conceptual framework. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. Band 31 (2006), p. 176.

- ↑ Necipoğlu 2008, p. 22.

- ↑ Vogüé 1864, p. 85.

- ↑ Oleg Grabar: The Meaning of the Dome of the Rock.

- ↑ Busse, Heribert (1991). "Zur Geschichte und Deutung der frühislamischen Ḥarambauten in Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins (in German). 107: 144–154. JSTOR 27931418.

- ↑ Richard Ettinghausen; Oleg Grabar; Marilyn Jenkins (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture 650–1250. Yale University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-300-08869-4.

- ↑ "Drawings of Islamic Buildings: Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009.

Until 1833 the Dome of the Rock had not been measured or drawn; according to Victor von Hagen, 'no architect had ever sketched its architecture, no antiquarian had traced its interior design...' On 13 November in that year, however, Frederick Catherwood dressed up as an Egyptian officer and accompanied by an Egyptian servant 'of great courage and assurance', entered the buildings of the mosque with his drawing materials... 'During six weeks, I continued to investigate every part of the mosque and its precincts.' Thus, Catherwood made the first complete survey of the Dome of the Rock, and paved the way for many other artists in subsequent years, such as William Harvey, Ernest Richmond and Carl Friedrich Heinrich Werner.

- 1 2 Goitein, Shelomo Dov (1950). "The historical background of the erection of the Dome of the Rock". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 70 (2): 104–108. JSTOR 595539.

- ↑ "Dome of the Rock". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ Amiran, D.H.K.; Arieh, E.; Turcotte, T. (1994). "Earthquakes in Israel and adjacent areas: macroseismic observations since 100 B.C.E.". Israel Exploration Journal. 44 (3/4): 260–305 [267]. JSTOR 27926357.

- ↑ Necipoğlu 2008, p. 31.

- ↑ Stark, Rodney. God's Battalions; a Case for the Crusades. Harper Collins, NY, 2009, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Clermont-Ganneau 1899, p. 179.

- ↑ St. Laurent, Beatrice; Riedlmayer, András (1993). "Restorations of Jerusalem and the Dome of the Rock and their political significance, 1537–1928" (PDF). In Necipoğlu, Gülru. Muqarnas. Volume 10: Essays in Honor of Oleg Grabar. Leiden: Brill. pp. 76–84. JSTOR 1523174.

- ↑ "Letter from Jerusalem: A Fight Over Sacred Turf by Sandra Scham". Archaeology.org. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ Business Optimization Consultants B.O.C. "Hashemite Restorations of the Islamic Holy Places in Jerusalem – kinghussein.gov.jo – Retrieved 21 January 2008". Kinghussein.gov.jo. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ Jerusalem's Holy Places and the Peace Process Marshall J. Breger and Thomas A. Idinopulos, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1998.

- ↑ Browning, Noah (15 August 2012). "Palestinians flock to Jerusalem as Israeli restrictions eased – Yahoo! News". News.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ Zivotofsky. "Tzarich Iyun: The Har HaBayit – OU Torah". OU Torah. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ↑ Braswell, G. Islam – Its Prophets, People, Politics and Power. Nashville, TN: Broadman and Holman Publishers. 1996. p. 14

- ↑ Ali, A. The Holy Qur'an – Translation and Commentary. Bronx, NY: Islamic Propagation Centre International. 1946. pp. 1625–31

- ↑ "Me'raj – The Night Ascension". Al-islam.org. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ "Meraj Article". Duas.org. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ Yakub of Syria (Ka'b al-Ahbar) Last Jewish Attempt at Islamic Leadership Committee for Historical Research in Islam and Judaism, © 2004–2012, accessed July 2013. "He continued to follow Rabbinic tradition such that later Islamic historians questioned whether he ever 'converted' to Islam."

- ↑ raisa (2014-07-30). "'Third Temple' crowdfunding plan aims to relocate Jerusalem's Dome of the Rock" (Text). The Stream - Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 2017-11-25.

- ↑ Stephen Spector, Evangelicals and Israel:The Story of American Christian Zionism, Oxford University Press, 2008 p. 202.

- ↑ Andrew Esensten U.S.-born Knesset candidate, Jeremy Gimpel, and his Dome of the Rock 'joke', Haaretz 20 January 2013.

- ↑ Burckhardt, Jacob; Peter Murray; James C. Palmes (1986). The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance. University of Chicago Press. p. 81.

References

- Creswell, K.A.C. (1924). The Origin of the Plan of the Dome of the Rock (2 Volumes). London: British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. OCLC 5862604.

- Peterson, Andrew (1994). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-06084-2

- Braswell, G. (1996). Islam – Its Prophets, People, Politics and Power. Nashville, TN: Broadman and Holman Publishers.

- Clermont-Ganneau, Charles (1899). "Chapter VIII The Kubbet es Sakhra". Archaeological Researches in Palestine During the Years 1873–1874. Volume 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. pp. 179–227.

- Necipoğlu, Gülru (2008). "The Dome of the Rock as palimpsest: 'Abd al-Malik's grand narrative and Sultan Süleyman's glosses" (PDF). In Necipoğlu, Gülru; Bailey, Julia. Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World. Volume 25. Leiden: Brill. pp. 17–105. ISBN 978-900417327-9.

- Ali, A. (1946). The Holy Qur’an – Translation and Commentary. Bronx, NY: Islamic Propagation Centre International.

- Islam, M. Anwarul; Al-Hamad, Zaid (2007). "The Dome of the Rock: origin of its octagonal plan". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 139 (2): 109–128. doi:10.1179/003103207x194145.

- Christoph Luxenberg: Neudeutung der arabischen Inschrift im Felsendom zu Jerusalem. In: Karl-Heinz Ohlig / Gerd-R. Puin (Hg.): Die dunklen Anfänge. Neue Forschungen zur Entstehung und frühen Geschichte des Islam, Berlin (Verlag Hans Schiler) 2005, S. 124–147. English version: "A New Interpretation of the Arabic Inscription in Jerusalem's Dome of the Rock". In: Karl-Heinz Ohlig / Gerd-R. Puin (eds.): The Hidden Origins of Islam: New Research into Its Early History, Amherst, N.Y. (Prometheus Books) 2010

- Vogüé, Melchior de (1864). Le Temple de Jérusalem : monographie du Haram-ech-Chérif, suivie d'un essai sur la topographie de la Ville-sainte (in French). Paris: Noblet & Baudry.

Further reading

- Grabar, Oleg (2006). The Dome of the Rock. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02313-0.

- Flood, Finbarr B. (2000). "The Ottoman windows in the Dome of the Rock and the Aqsa Mosque" (PDF). In Auld, Sylvia; Hillenbrand, Robert. Ottoman Jerusalem: The Living City: 1517–1917. Volume 1. London: Altajir World of Islam Trust. pp. 431–463. ISBN 978-1-901435-03-0.

- Kessler, Christel (1964). "Above the ceiling of the outer ambulatory in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (3/4): 83–94. JSTOR 25202759.

- Kessler, Christel (1970). "'Abd Al-Malik's inscription in the Dome of the Rock: a reconsideration". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1): 2–14. JSTOR 25203167.

- Richmond, Ernest Tatham (1924). The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem: A Description of its Structure and Decoration. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- St. Laurent, Beatrice (1998). "The Dome of the Rock and the politics of restoration". Bridgewater Review. 17 (2): 14–20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dome of the Rock. |

- "Qubba al-Sakhra, Jerusalem". Archnet Digital Archive.

- Dome of the Rock Sacred sites

- The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem Masterpieces of Islamic Architecture

- Ochs, Christoph (2010). "Dome of the Rock". Bibledex in Israel. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

- Allen, Terry (2014). "The Marble Revetment of the Piers of the Dome of the Rock". Occidental, CA: Solipsist Press. Retrieved 26 March 2017.