Abu Ghosh

Abu Ghosh

| ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| ||

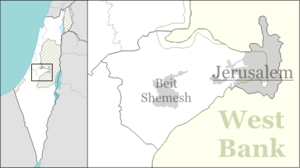

Abu Ghosh Location within Israel | ||

| Coordinates: 31°48.288′N 35°6.744′E / 31.804800°N 35.112400°ECoordinates: 31°48.288′N 35°6.744′E / 31.804800°N 35.112400°E | ||

| Grid position | 160/134 PAL | |

| District |

| |

| Founded |

7000 BCE (Earliest settlement) 16th century (Abu Ghosh clan arrives) | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Local council | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 2,500 dunams (2.5 km2 or 600 acres) | |

| Population (2017)[1] | ||

| • Total | 7,332 | |

| • Density | 2,900/km2 (7,600/sq mi) | |

Abu Ghosh (Arabic: أبو غوش; Hebrew: אבו גוש) is an Arab-Israeli local council in Israel, located 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) west of Jerusalem on the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem highway. It is situated 610–720 meters above sea level. It takes its current name from the dominant clan inhabiting the town, while the older Arabic name used to be Qaryat al-'Inab ("Grape Village").[2]

History

Prehistory

Abu Ghosh is located in one of the earliest areas of human habitation in Israel.[2] Archaeological excavations have revealed three Neolithic settlement phases, the middle phase is dated to the 7th millennium BCE.[3]

Biblical era

The old Arabic name of Abu Ghosh, Qaryat al-'Inab ("Village of the Grapes"), has led to its identification with the biblical site of Kiryat Ye'arim, known in English as Kiriath-jearim (Hebrew meaning: "Village of Woods"),[2] the town to which the Ark of the Covenant was taken after it had left Beth-shemesh.[4]

The village has also been associated with Anathoth, the birthplace of the prophet Jeremiah.[5]

Roman and early Muslim periods

Legio X Fretensis of the Roman army had a station house in Abu Ghosh until the end of the 3rd century CE.[2]

In 1047 Nasir Khusraw passed by it when he traveled from Ramla to Jerusalem. He noted: "By the wayside I noticed, in quantities, plants of rue (Sadab), which grows here of its own accord on these hills, and in the desert places. In the village of Kariat-al-'Anab there is a fine spring of sweet water gushing out from under a stone, and they have placed all around troughs, with small buildings contiguous (for the shelter of travellers)."[6][7]

Crusader period

The Crusaders, who called the village Fontenoid, thought for a while that this was the site of Emmaus mentioned in the Gospel of Luke. For the church they built here see here or further down under "Benedictine monastery".

Ottoman period

In the early Ottoman census of 16th century, it was noted as Inab, a village located in the nahiya of Quds.[8]

There are several versions on the origins of the Abu Gosh clan: According to one version, Abu Ghosh is the name of an Arab family who settled at the location in the early 16th century.[2] According to the Abu Gosh family tradition, they were of Chechen descent, and their founder fought with Selim I.[9] In the 18th century, they lived in a village near Bayt Nuba, from which they ruled the surrounding region.[9] However, according to the tradition, the Banu 'Amir tribesmen and the villagers of Beit Liqya rose against them and slaughtered the entire Abu Ghosh clan except for one woman and her baby, who continued the Abu Ghosh name.[9] Some, however, assert that the Abu Gosh are indeed of North Caucasian traditional descent is correct, but the family is of Ingush origin and that "Abu Gosh" is in fact a corruption of "Abu Ingush".[10]

The Abu Gosh family controlled the pilgrimage route from Jaffa to Jerusalem, and imposed tolls on all pilgrims passing through.[2] They were given this privilege during the sultanate of Suleiman the Magnificent (1494-1566).[11] The churches in Jerusalem also paid a tax to the Abu Ghosh clan.[2][12] In 1834, during Egyptian period in Palestine, the Egyptian governor Ibrahim Pasha abolished the Abu Ghosh's right to exact tolls from the pilgrimage route and imprisoned the clan's chief, Ibrahim Abu Ghosh, leading to the clan's temporary participation in the countrywide Peasants' Revolt.[13] As a result, Abu Ghosh was attacked by Egyptian military forces.

In 1838, it was noted as a Muslim village, named Kuryet el'-Enab, located in the Beni Malik district.[14]

It was attacked again in 1853 during a civil war between feudal families under Ahmad Abu Ghosh who ordered his nephew Mustafa to go to battle. A third attack on Abu Ghosh, carried out by the Ottoman military forces, helped and executed by British forces, took place during the military expedition against the feudal families in the 1860s. The Abu Ghoshes were among the well-known feudal families in Palestine. They governed 22 villages.[15] The sheikh of Abu Ghosh lived in an impressive house described by pilgrims and tourists as a "true palace..., a castle..., a protective fortress..."[16]

An Ottoman village list of about 1870 showed that Abu Ghosh had 148 houses and a population of 579, though the population count included men, only.[17][18]

In the 19th century, the village was also referred to as Kuryet el' Enab.[19]

In 1896 the population of 'Abu Ghosch was estimated to be about 1,200 persons.[20]

Kiryat Anavim, the first kibbutz in the Judean Hills, was founded near Abu Ghosh in 1914, on land purchased from the Abu Ghosh family.[21]

British Mandate

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Enab had a population 475, 450 Muslims and 25 Christians,[22] increasing in the 1931 census to 601; 576 Muslims and 25 Christians, in 138 houses.[23]

When Chaim Weizmann, later the first president of the State of Israel, visited Palestine in the spring of 1920, he was hosted by the residents of Abu Ghosh.[21] From the early 20th century, the leaders of Abu-Ghosh worked together and were on friendly terms with the Zionist leaders,[24] and local Jews.[25]

In the 1945 Village Statistics the population of Qaryat el 'Inab (Abu Ghosh) was 860; 820 Muslims and 40 Christians,[26] with a total of 7,590 dunams of land according to an official land and population survey.[26][27] Of this, a total of 1,517 dunams were plantations and irrigable land, 3,274 for cereals,[26][28] while 21 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[26][29]

In 1947-1948, the road to Jerusalem was blocked, as passage through the hills surrounding Jerusalem was crucial for getting supplies to the Jewish parts of the besieged city. Of the 36 Arab Muslim villages in these hills, Abu Ghosh was the only Muslim one that remained neutral, and in many cases helped to keep the road open for Jewish convoys. "From here it is possible to open and close the gates to Jerusalem," said former President Yitzhak Navon.[30] Many in Abu Ghosh helped Israel with supplies.[31]

During Operation Nachshon the Haganah reconsidered an attack on Abu Ghosh due to opposition of the Stern Gang, whose local commanders were on good terms with the mukhtar (village chief).[32]

Israeli rule

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, the Har'el Brigade headquarters were located in Abu-Ghosh.[33] Many of the villagers left Abu Ghosh during the heavy fighting in 1948, but most returned home in the following months.

The Israeli government, subsequently on peaceful terms with the village, invested in improving the infrastructure of the village.[34]

During the early years of the state of Israel the village was subjected to repeated searches by the army and anyone who had not registered as resident in November 1948 could be expelled. One case attracted a lot of public criticism. In June 1950, the IDF and police rounded up 105 men and women believed to be infiltrators were deported to Jordan. In an open letter to the Knesset, the inhabitants of Abu Ghosh claimed that the army had "surrounded our village, and taken our women, children and old folk, and thrown them over the border and into the Negev Desert, and many of them died in consequence, when they were shot [trying to make their way back across] the borders."[35] The letter further stated that they woke up to "shouts blaring over the loudspeaker announcing that the village was surrounded and anyone trying to get out would be shot....The police and military forces then began to enter the houses and conduct meticulous searches, but no contraband was found. In the end, using force and blows, they gathered up our women, and old folk and children, the sick and the blind and pregnant women. These shouted for help but there was no saviour. And we looked on and were powerless to do anything save beg for mercy. Alas, our pleas were of no avail... They then took the prisoners, who were weeping and screaming, to an unknown place, and we still do not know what befell them."[35]

Knesset member Moshe Erem accused the army of excessive force, a charge that Prime Minister Ben Gurion denied. He also defended the policy of expulsions. Foreign Minister Sharett, concerned about international reaction, argued that there should be more searches with fewer people being deported at one time and then only adult males. One of the issues causing concern in this case was that some of those expelled had been resident in Abu Ghosh for over a year. In the wake of public pressure, the vast majority of villagers were allowed to return.[35] In July 1952, MK Beba Idelson objected to the deportation of an Abu Ghosh woman, who was said to have cancer, and her four children. The police minister Bechor-Shalom Sheetrit rejected the claim that the woman had cancer.[36] The village remained under martial law until 1966.

Abu Ghosh mayor Salim Jaber attributed the good relations with Israel to the great importance attached to being hospitable: "We welcome anybody, regardless of religion or race."[37] According to a village elder interviewed by The Globe and Mail: "Perhaps because of the history of feuding with the Arabs around us we allied ourselves with the Jews...against the British. We did not join the Arabs from the other villages bombarding Jewish vehicles in 1947. The Palmach fought many villages around us. But there was an order to leave us alone. The other Arabs never thought there would be a Jewish government here...During the first truce of the War of Independence, I was on my way to Ramallah to see my father and uncles, and I was captured by Jordanian soldiers. They accused me of being a traitor and tortured me for six days."[37]

In 2017, Abu Ghosh was described as a "model of coexistence."[38]

Local government

Abu Ghosh is governed by a local council, and is part of the Jerusalem District. The current mayor of Abu Ghosh is Salim Jaber. According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Abu Ghosh had a population of 7,332 in 2017.[1]

Religious sites

Benedictine Monastery

The Crusader church at the historical entrance to the village, now at the centre of the Benedictine Monastery, is one of the best preserved Crusader remains in the country. The Hospitallers had built this late Romanesque/earlyGothic[39] church in 1140[40] and it was partially destroyed in 1187. It was acquired by the French government in 1899 and placed under guardianship of the French Benedictine Fathers. Since 1956, it has been run by the Lazarist Fathers. Today a double community of nuns and brothers continue the worship in the church and offer hospitality, reflecting the ancient story of the couple on the Jerusalem–Emmaus road.[40] Edward Robinson (1838) described it as "obviously from the time of the crusades, and [...] more perfectly preserved than any other ancient church in Palestine." Excavations carried out in 1944 confirm that the Crusaders identified the site as the biblical Emmaus. The church is now known as both Church of the Resurrection and Emmaus of the Crusaders.[41]

Church of Notre Dame

The Church of Notre Dame de l'Arche d'Alliance (Our Lady of the Ark of the Covenant Church), built in 1924, is said to occupy the site of the house of Abinadab, where the Ark of the Covenant rested for twenty years until King David took it to Jerusalem. It is built on the site of a fifth-century Byzantine church.[42] It is recognizable by the roof-top statue of Mary carrying the infant Jesus in her arms.

Abu Ghosh mosques

Abu Ghosh's historic mosque is in the town center. Akhmad Kadyrov Mosque, the new mosque completed in 2014, is the largest mosque in Israel. Built with money donated by the Chechen government.[43]

Music and culture

The Abu Gosh Music Festival is held twice a year, in the fall and late spring, with musical ensembles and choirs from Israel and abroad performing in and around the churches in Abu Ghosh.[44] The Elvis Inn, a restaurant in Abu Ghosh, is known for its large gold statue of Elvis Presley in the parking lot.[45]

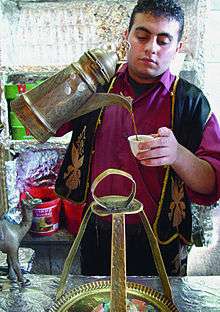

Local cuisine

Abu Ghosh is popular among Israelis for its Middle Eastern restaurants and hummus.[46] In 2007, it was described as the "hummus capital of Israel."[47] In January 2010, Abu Ghosh secured the Guinness World Record for preparing the largest dish of hummus in the world. Jawdat Ibrahim, owner of Abu Ghosh hummus restaurant, organized the event, which brought together 50 Jewish and Israeli-Arab chefs. The winning 20-foot (6.1 m) dish weighed 4,087.5 kilograms (8992.5 pounds), about twice as much as the previous record set by Lebanon in October 2009.[48][49][50] In May 2010, Lebanon regained the Guinness World Record, more than doubling Abu Ghosh's January 2010 total.[51]

Chametz ceremony

Since 1997, Jaaber Hussein, a Muslim Arab-Israeli hotel food manager from Abu Ghosh, has signed an agreement with Israel's Chief Rabbis to purchase all of the state's chametz, the leavened products not kosher for the Jewish holiday of Passover. This contractually binding deal allows the state to respect religious edicts without wastefully destroying massive quantities of food. In 2009, Hussein put down a cash deposit of $4,800 (about 20,000 shekels) for $150 million worth of chametz, acquired from state companies, the prison service and the national stock of emergency supplies. At the end of Passover each year, the deposit is returned to Hussein and the state of Israel buys back all the food products.[52][37]

Abu Ghosh 1948

Abu Ghosh 1948 Abu Gosh 1948. Police station in foreground.

Abu Gosh 1948. Police station in foreground. Abu Ghosh Police Station used as headquarters by Harel Brigade, 1948

Abu Ghosh Police Station used as headquarters by Harel Brigade, 1948 View of Abu Ghosh 1948

View of Abu Ghosh 1948

See also

References

- 1 2 "List of localities, in Alphabetical order" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sharon, 1997, pp. 3-13

- ↑ Avraham Negev, Shimon Gibson (2005) Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 0-8264-8571-5

- ↑ I Samuel 6:1–ff.

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, p. 18

- ↑ Khusraw, 1897, p. 22

- ↑ le Strange, 1890, p. 481

- ↑ Toledano, 1984, p. 294, has Inab at location 35°06′05″E 31°48′25″N.

- 1 2 3 Ruth Kark and Michal Oren-Nordheim (2001). Jerusalem and its Environs. Hebrew University Magnes Press. pp. 230–231. ISBN 0-8143-2909-8.

- ↑

- ↑ Spyridon, 1938, p. 79.

- ↑ "2BackToHomePage3".

- ↑ Rood, 2004, pp. 123-124

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 3, 2nd appendix, p. 123

- ↑ Finn, 1878, p. 230

- ↑ Johann Nepomuk Sepp, Jerusalem und das heilige Land: Pilgerbuch nach Palästina, Syrien und Aegypten, Schaffhausen 1863, 1st of 2 volumes, p. 150; see also Constantin Tischendorf, Aus dem Heiligen Lande, Leipzig 1862, p. 165f; Schölch, Alexander (1993), Palestine in Transformation, 1856-1882: Studies in Social, Economic, and Political Development, Institute for Palestine Studies, ISBN 0-88728-234-2

- ↑ Socin, 1879, p. 142

- ↑ Hartmann, 1883, p. 118, noted 149 houses in Karjet el-'Ineb

- ↑ Survey of Western Palestine, 1870. Index page 3.

- ↑ Schick, 1896, p. 125

- 1 2 Army of shadows: Palestinian collaboration with Zionism, 1917 – 1948 / Hillel Cohen Archived 9 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 14

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 40

- ↑ Army of Shadows: Palestinian Collaboration with Zionism, 1917-1948, By Hillel Cohen, Page 78

- ↑ No balm in Gilead: a personal retrospective of mandate days in Palestine (1989), By Sylva M. Gelber, page 21

- 1 2 3 4 Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 25

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 58

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 103

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 153

- ↑ Abu Ghosh - The Saga of an Arab Village Archived 6 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine., Israel Magazine-On-Web (Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs), June 2000

- ↑ Army of Shadows: Palestinian Collaboration with Zionism, 1917-1948, Hillel Cohen, Page 232-244

- ↑ Pappe, Ilan (2006) The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. Oneworld. ISBN 1-85168-467-0. p.91.

- ↑ Har’el: Palmach brigade in Jerusalem, Zvi Dror (ed. Nathan Shoḥam), Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishers: Benei Barak 2005, p. 273 (Hebrew)

- ↑ My world as a Jew: the memoirs of Israel Goldstein, Volume 2, (Associated University Presses, 1984) Page 163

- 1 2 3 Morris, pp. 267-69

- ↑ Morris, Benny (1993) Israel's Border Wars, 1949 - 1956. Arab Infiltration, Israeli Retaliation, and the Countdown to the Suez War. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-827850-0. p.152

- 1 2 3 One Muslim key to Passover's food ritual, The Globe and Mail, 5 April 2007

- ↑ Gunman kills Israelis

- ↑ "A Crusader era church, great Middle Eastern food, and the battle for the road to Jerusalem". Travel blog by Ethan Bensinger, 2007.

- 1 2 Women of Bible lands: a pilgrimage to compassion and wisdom By Martha Ann Kirk, page 143

- ↑ "The Catholic Church Of The Holy Land » Benedictines: Mount Olivet. Abu Gosh".

- ↑ Israel and the Palestinian territories: the rough guide By Daniel Jacobs, Shirley Eber, Francesca Silvani, by Daniel Jacobs, Shirley Eber, Francesca Silvani, 1998, page 126

- ↑ The New Mosque of Abu Ghosh: March 23rd, 2014 Inauguration ceremony

- ↑ CoMedia Group LTD. "פסטיבל אבו גוש : עמוד הבית".

- ↑ CNN, "Destination Elvis", August 1997

- ↑ "Itineraries in Conflict".

- ↑ Israel & the Palestinian territories, Lonely Planet, 2007, Michael Kohn, page 145

- ↑ "Abu Gosh mashes up world's largest hummus". YNet. AFP. 8 January 2010.

- ↑ "Abu Ghosh secures Guinness world record for largest dish of hummus". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 11 January 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ↑ Jack Brockbank (12 January 2010). "The largest serving of hummus". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ↑ "Lebanon breaks Israel's hummus world record". The Jerusalem Post. Associated Press. 9 May 2010.

- ↑ Ben Lynfield (6 April 2009). "The Muslim guardian of Israel's daily bread". The Independent.

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H. H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (pp. 18, 43, 132-133)

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Finn, J. (1878). E. A. Finn, ed. Stirring Times, or, Records from Jerusalem Consular Chronicles of 1853 to 1856. Edited and Compiled by His Widow E. A. Finn. With a Preface by the Viscountess Strangford. 1. London: C.K. Paul & co.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (1994). "Beit Naqquba, Al Fureidis". 1948 and after; Israel and the Palestinians. Oxford University Press. pp. 257–289. ISBN 0-19-827929-9.

- Mukaddasi (1886). Description of Syria, including Palestine. London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Nasir-I-Khusrau; et al. (1897). Vol IV. A journey through Syria and Palestine (1047 CE.). The pilgrimage of Saewolf to Jerusalem. The pilgrimage of the Russian abbot Daniel. London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (p. 321)

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. p. 335

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Rood, Judith Mendelsohn (2004). Sacred Law In The Holy City: The Khedival Challenge To The Ottomans As Seen From Jerusalem, 1829-1841. BRILL. ISBN 9789004138100.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Sharon, M. (1997). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, A. 1. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10833-5.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Spyridon, S. N. (1938). "Annals of Palestine". Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society. XVIII: 65–111.

- Strange, le, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. OCLC 1004386.

- Toledano, E. (1984). "The Sanjaq of Jerusalem in the Sixteenth Century: Aspects of Topography and Population". Archivum Ottomanicum. 9: 279–319.

External links

- Welcome To Qaryet al-'Inab/Abu Goush

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons